Abstract

Objectives:

Tobacco company conduct has been a central concern in tobacco control. Nevertheless, the public health community has not taken full advantage of the large economics and marketing literature on market competition in the cigarette industry.

Methods:

We conducted an unstructured narrative review of the economics and marketing literature using an antitrust framework that considers: 1) market; definition, 2) market concentration; 3) entry barriers; and 4) firm conduct.

Results:

Since the 1960s, U.S. cigarette market concentration has increased primarily due to mergers and growth in the Marlboro brand. Entry barriers have included brand proliferation, slotting allowance contracts with retailers and government regulation. While cigarette sales have declined, established firms have used coordinated price increases, predatory pricing and price discrimination to sustain their market power and profits.

Conclusions:

Although the major cigarette firms have exercised market power to increase prices and profits, the market could be radically changing, with consumers more likely to use several different types of tobacco products rather than just smoking a single cigarette brand. Better understanding of the interaction between market structure and government regulation can help develop effective policies in this changing tobacco product market.

Keywords: cigarette, industry, market competition

INTRODUCTION

In the early 1900s, the American Tobacco Company controlled the US cigarette market, but antitrust laws split the monopoly into four smaller companies: RJ Reynolds, Lorillard, Liggett & Myers, and American Tobacco. Brown & Williamson and Philip Morris later emerged as major cigarette firms, and by 1950 these six major companies dominated the cigarette market. Through various consolidations, the US cigarette industry today is dominated by two major companies – Altria (formerly Philip Morris) and RAI (US subsidiary of BAT), with the remainder comprised of smaller firms (ITG Brands, Liggett Group, Vector Tobacco, and regional and discount firms).

While the tobacco control literature regularly considers tobacco company behaviors (especially marketing and political activity),1–4 it does not often consider market structure and conduct. At the same time, public health experts and policy makers have given limited attention to a large economics and marketing literature that considers the structure of the cigarette market, and how established firms gain and maintain market power (eg, by preventing market entry), and respond to government regulation. That literature considers the impact on market competition of advertising, brand extensions, and slotting allowance contracts (which control pricing and promotions and limited retail shelf space, ads, and product displays), all issues of central importance to tobacco control.

This study presents an unstructured, narrative review of the economics and marketing literature on competition and market power in the cigarette market, using a well-accepted framework for analyzing market competition. Our aim is to help understand the growth and maintenance of market power in the U.S. cigarette market and its relevance to understanding firm behavior in response to past tobacco control policies and potential future policies.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic search for economic and marketing studies relating to the U.S. tobacco market. We searched online databases (e.g., EconLit, Web of Science, Social Science Research Network, and the Federal Trade Commission website) and reference lists published through December 2016 that included at least one product term (“cigar”, “cigarette”, “cigarillo”, “smokeless tobacco”, or “tobacco”) and one market term (“advertising”, “antitrust”, “cigarette tax”, “competition”, “industry”, “marketing”, “markets”, “price”, “slotting allowance”). Having found few studies that examined other tobacco product markets (eg, cigars), we focus on the cigarette market. After omitting papers not related to market competition (e.g., most demand studies), we identified 108 publications in economics and marketing journals covering a variety of often overlapping topics.

We then conducted an unstructured, narrative review to provide key insights from the literature relevant to tobacco control. Rather than attempting to be exhaustive or determine precise effect sizes, our goal was to identify key results, including inconsistent findings.

As a guiding framework, we applied the four-step antitrust approach described in the U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Horizontal Merger Guidelines (HMG):5 1) defining the relevant market for the evaluation competition; 2) evaluating the level of and changes in market concentration; 3) identifying the level of entry barriers; and 4) examining anticompetitive conduct of firms in the market.6 While the HMG focus on mergers, they provide a unified framework for analyzing the impact of other industry behaviors on market concentration and competition and are similar to other nations’ antitrust guidelines.7,8

The central concern in the economics literature is the harm to consumers from paying higher prices or having fewer products or product variants available due to “market power.” This perspective differs from a public health concern where harm to consumers is evaluated primarily in terms of reduced negative health outcomes, which may be improved through higher prices.9 In our discussion below, we attempt to distinguish these conflicting perspectives.

MARKET DEFINITION

When defining the relevant market, the HMG considers whether customers are willing and able to switch to other substitute products when faced with price increases. In the 2014 Reynolds American-Lorillard merger consent decree, the FTC declared that traditional combustible cigarettes alone were the relevant market, because “Consumers do not consider alternative tobacco products to be close substitutes for cigarettes. Cigarette producers similarly view cigarettes and other tobacco products as separate product categories, and cigarette prices are not significantly constrained by other tobacco products.”10 This 2014 market definition is consistent with 191111 and 194612 antitrust decisions, and the FTC’s 2004 Reynolds-Brown & Williamson merger analysis.13

While the 2014 Reynolds-Lorillard merger analysis considered cigarettes to be the relevant market, the FTC noted that “cigarettes are highly differentiated products, and producers compete across a number of dimensions,” especially “brand equity,” with the agency distinguishing premium flagship brands, such as Marlboro and Camel, from other brands.13 The FTC also considered submarkets, finding the menthol cigarette sub-market important enough to require Reynolds to sell its Kool menthol brand to maintain competition in that sub-market.10

Consistent with FTC and court analyses, the economics and marketing literature focuses on conventional cigarettes as the relevant market, because of only limited substitution with other products. However, the literature (as described below) was mostly published before 2005, and the use of other nicotine-delivery products, such as little cigars, smokeless tobacco, and e-cigarettes has increased in recent years,14,15 often used in conjunction with cigarettes.16 Consequently, some of these other products could be seen as complements (ie, used in conjunction) with or substitutes for cigarettes, suggesting a possible change in the market definition, and become particularly relevant from a public health perspective.

Although the FTC and court antitrust analyses have defined the market as the entire U.S., geographic submarkets (eg, states, regions) may also be relevant. For example, Keeler et al.17 and Gallet18 found that cigarette companies price discriminate by state, suggesting relevant state submarkets. Geographic sub-markets may also be relevant to public health analyses, given that the prevalence of different types of tobacco use and the tobacco control policies of different states or even cities show considerable variation.19

MARKET CONCENTRATION

Industry concentration in the defined market is based on the number of firms and their market shares, (eg, firm sales relative to total industry sales). A standard indicator of market power, the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (“HHI”), adds individual firms’ squared market shares, thereby giving proportionately greater weight to those with larger market shares. The HMG classifies markets with HHI<1500 as unconcentrated (“unlikely to have adverse competitive effects”), 1500≤HHI< 2500 as moderately concentrated (“raises significant competitive concerns”), HHI> 2500 as highly concentrated (“likely… market power”).5 For example, a moderately concentrated market could have two companies with a 30% market share or one company with a 40% share and other firms having 10% or less.

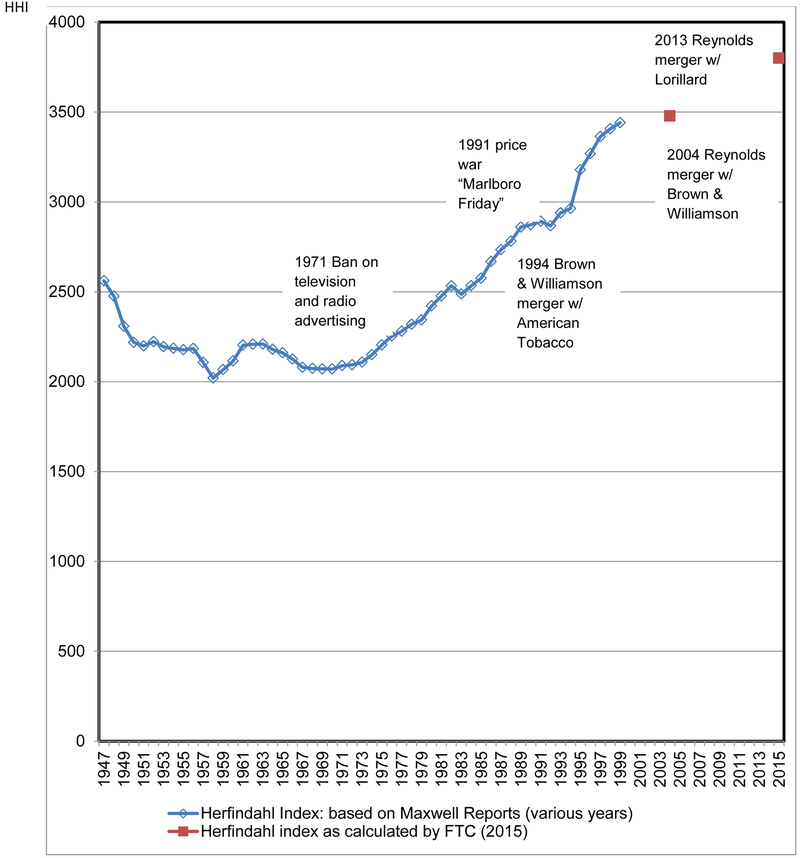

Figure 1 shows the related trends in HHI based on data from Maxwell Reports20 and HHI estimates from FTC analyses of the Reynolds-Lorillard merger.21 Following a dip from 2560 in 1947 to 2000 in 1958, the HHI increased to 2900 by 1991 and the cigarette market has since remained highly concentrated. Much of this increase came from Philip Morris’s market share rising from 7% in 1949 to 42% in 1990,22 with its Marlboro’s share growing from 5% in 1957 to 30% by 1995. There was a dramatic increase in the number of brands between 1972 and 1998.23,24 While many of the brands were unsuccessful, the introduction of new sub-brands building on the reputation of their established major brands (eg, Marlboro Menthol, Camel Light) appears to have contributed to an increase in major firm’s market shares.20

Figure 1.

Herfindahl Index of Industry Concentration, Cigarette Industry, 1947–2015

Since 1993, concentration has increased primarily from mergers. Brown & Williamson acquired American Tobacco in 1994, and Reynolds acquired Brown & Williamson in 2004 and Lorillard in 2013. By 2015, the HHI was about 3800,21 with Philip Morris USA’s market share at 47% (and Marlboro at 41%) and Reynolds American at 34%.21 Although some new firms have entered the market since 1999, their market shares have not exceeded 2%.

Although the public health emphasis is often on the ability of large firms to influence public policy rather than on other impacts of market concentration,1–4 high levels of concentration are important to market power and its related impacts on pricing, market entry, and competition. In addition, market concentration has provided the major cigarette firms with higher profits that they have used to support intensive lobbying, lawsuits, and other activities to block, delay, or weaken tobacco control efforts. In addition, the incentives to lobby against tobacco control policies increase when firms have large market shares, since a larger share of the gains then accrue to those firms.

ENTRY BARRIERS

The ability to maintain high concentration depends on barriers to market entry. According to the HMG,5 firms are unlikely to exercise market power unless entry barriers are high enough to keep new firms or existing small firms from gaining market share through offering lower prices. Government regulations can impede market entry both by establishing direct restrictions on entry and by increasing the sunk-cost (ie, irrecoverable) investments requirements to introduce a new brand. These sunk cost investments may include the costs of product development, establishing production and distribution capacities, marketing and regulatory compliance.25 The economics and marketing literature has identified four types of entry barriers relevant to the cigarette industry: advertising, brand proliferation, retail slotting contracts, and legal/regulatory costs.

Advertising

Advertising can create entry barriers when market entrants cannot readily take advantage of the economies of scale that large established firms enjoy in their ongoing advertising or when past advertising has created brand loyalty for existing firms.26,27

While existing firms may produce at a level where advertising economies of scale have been exhausted, entrants may find it difficult to reach that level. The economics literature is mixed on the role of scale economies in cigarette advertising. Brown28 found advertising economies over a wide range of cigarette sales, especially for new brands, but Peles,29 Schmalensee30 and Thomas31 did not find significant scale economies. However, an efficient scale may be more difficult to reach in recent years with more rapidly declining demand.

Whether or not scale economies apply, the cost of cigarette advertising to establish a new brand may still create an entry barrier. Investments in advertising yield “first mover advantages” to incumbent firms, who have already built a reputation that must be overcome in order to attract customers from those firms.26,27 These disadvantages are enhanced when reputation is gained slowly over time, the transference of brand loyalty from cigarettes to non-tobacco products is limited, and in a declining market demand (eg, due to low levels of initiation or increased cessation).

One study reported short-lived effects of cigarette advertising on sales, implying a limited role for brand loyalty,28 but others, including a detailed interindustry analysis found slow advertising depreciation.29,32,33,34 A systematic review of the marketing literature found cigarette advertising to be an important predictor of brand loyalty.35 Other research found that brand loyalty for cigarettes was high and increasing over time.36 This was especially true for more popular brands, with Marlboro at the high end.37 Consistent with brand loyalty, other studies have found that cigarette advertising is associated with higher prices26,38 and consumers were reluctant to switch brands.39

Much of the public health literature40,41 on cigarette media advertising also focuses on brand loyalty. Much of the focus is on its role in increasing initiation,15 consistent with the marketing literature35 (see especially Pollay et al.42).

Brand Proliferation

As noted above, the dominant cigarette companies have taken advantage of consumer familiarity with their most popular brands by marketing sub-brands. Indeed, brand proliferation by established firms can create an entry barrier when brands are densely packed across product dimensions (eg, menthol, light/low, full flavor, women-focused, premium, low-cost).43 With no market niche available, it is more difficult for new brands to distinguish themselves from established brands and sub-brands. This phenomenon has been identified in empirical inter-industry studies and validated by complementary theoretical models.44

Cigarettes have been associated with specific product attributes, such as nicotine and tar content, length, flavor and thickness.45 Labeling and advertising can also create different perceived brand characteristics separate from product attributes, eg, establishing Marlboro as a masculine brand and promoting Virginia Slims as a women’s cigarette. Cigarettes have been found more generally to be differentiated along horizontal (brand attributes, such as light vs regular, length) and vertical (perceived quality, such as premium vs. regular) dimensions.46

Larger, established cigarette companies have been found to have a distinct advantage from extending their brands into new product lines, with their market share increasing along with the strength and symbolic value of the parent brand.47 More broadly, one study found that the introduction of new brands rather than advertising was associated with increased demand,48 and brand extensions became increasingly important over the product life cycle as the relative importance of advertising declined.49

The public health literature has considered sub-brands primarily as an industry tactic to target specific market segments or mislead customers.15 For example, menthol brands were used to attract new market segments,20 and the industry introduced“ low tar” and “lights” in the sixties as a “reduced-harm” alternative to quitting.50 Often neglected is their role in increasing and protecting market power.

Retail Slotting Allowances

Slotting allowances, whereby firms pay for limited retail shelf space leaves less space available for new entrants.25 This capability is greatest in markets like cigarettes that are dominated by large manufacturers with a wide range of established brands25,51,52 and where there is limited ability to expand the market (ie, indicated by relative insensitivity to price).53 While some studies suggest efficiency gains from slotting allowances, such as reduced prices, planning shelf space allocations and encouraging retailers to carry new products,51,52,54 other analyses show that slotting allowances can limit consumer choice, and increase consumer prices and industry profits.55–59 In the most extensive study across different industries,60 slotting allowances were found to increase market power more than promote economic efficiency.

The cigarette industry was one of the first US industries to implement slotting allowances.61–63 With limits on most other forms of advertising, slotting allowances became an important part of promotional agreements.64 While the primary purpose of these allowances was generally to pay for shelf space, slotting allowance agreements often included provisions for product and advertising displays, payments for retailer price promotions, and rewards for meeting sales quotas.62,64–66 According to the 2014 FTC Cigarette Report,50 the major cigarette firms spent $11.2 billion on advertising and promotions, of which 2.8% was for point-of sale displays, 7.5% for promotional allowances, and 66% for retailer price discounts. As discussed below, retailer price discounts can be used to target new entrants or smaller firm, as well as to selectively lower prices to gain new customers. In particular, these agreements can complement brand proliferation strategies which crowd out new brands.

A 2002 antitrust case unsuccessfully challenged Phillip Morris’s Retail Leaders program, which paid retailers increasingly large retail display allowances in exchange for greater commitments of display, advertising, and promotion space.67 However, in the same year, slotting fees in the smokeless tobacco market were found exclusionary.67 In evaluating the 2014 RJR-Lorillard merger, the FTC21 also raised concerns about RJR’s Everyday Low Price Program, which constrained retailers from undercutting the price of RJR’s Pall Mall brand. A 2004 analysis68 found slotting allowances to be anticompetitive, with Phillip Morris and RJR initially controlling 85% to 90% and increasing to 95% of shelf space after the Reynolds-Brown & Williamson merger. In addition, changes in relative prices, especially those from promotions linked to slotting allowances, have been associated with changes in firms’ market shares.69

Studies in the tobacco control literature65 have focused primarily on the role of product displays in encouraging smoking initiation and discouraging cessation through advertising. However, they have largely overlooked the role of slotting fees and the related agreements in enabling established firms’ ability to control the retail marketplace by limiting shelf space and using price promotions to reduce entry.

Legal/Regulatory Costs

The economics literature has examined the impact on market entry and competition from three types of regulatory constraints: 1) the cigarette advertising ban on TV and radio media imposed by the 1971 Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act (FCLAA), 2) requirements and advertising restrictions of the 1998 MSA, and 3) legal challenges.

Studies find direct links between the FCLAA TV and radio advertising ban and market competition. Firm market shares became more unstable and firm profitability increased,70–72 producing abnormally high stock returns (as reflective of profits).73 Although one study questioned whether the broadcast ban increased market power,74 three others found that industry concentration increased,22,75,76 and another found that the restrictions facilitated coordinated pricing behavior among established firms.77 The ban was also found to slow the introduction of new brands, especially those with low tar, suggesting that the bans may have discouraged the entry of firms producing new products.78

Indirect evidence on the effect of advertising restrictions is provided by studies that consider cigarette demand. With one exception,79 studies in the economics literature have found minimal effects of advertising on overall cigarette demand in the UK80 and the US.81–83 An Australian study84 referred to a “reciprocal cancellation effect,” finding that advertising led to market shares changes rather than increased overall demand. A meta-analysis85 found that advertising increased cigarette demand prior to 1971, but has since had a more limited effect. This literature suggests that cigarette manufacturers would benefit from uniformly reducing their advertising expenditures to reduce costs and thereby increase profits, as occurred following the FCLAA’s advertising restrictions.86,87

These studies provide a different perspective than those in the public health literature, which focuses primarily on the relationship of advertising restrictions to smoking rates. This literature finds advertising restrictions associated with reduced cigarette sales, especially complete bans, with a stronger association in in high than low income nations.88–90 Consistent with these findings, recent reviews in the marketing literature91,92 have concluded that advertising bans have less effect on consumer demand in more mature markets (typically higher income nations), which is viewed as advertising increasing demand in the early stages of the product life cycle and primarily buildings selective brand loyalty in the later stages. Often neglected in the public health literature is the role that the FCLAA may have played in possibly discouraging the entry of firms producing at lower prices and providing new products.

The 1998 MSA required payments from U.S. cigarette companies to the 46 U.S. states and territories that had not already reached similar individual settlements and established new advertising restrictions.93 The MSA helped to create new entry barriers for lower-cost firms and brands by requiring states to implement and actively enforce new laws to make non-settling firms pay special non-participating manufacturer fees if they did not join the settlement, make settlement payments, and abide by its advertising restrictions and other requirements.94

Studies have found direct associations of the MSA with promotions, pricing and market power. One study found95 that the MSA eventually prompted greater promotional allowances and price discounting at retail outlets. Similarly, an FTC Cigarette Report50 finds that, soon after the MSA, major firms substantially increased price discounts and promotional allowances at the wholesale and retail levels, indicative of an increasing role of slotting allowances. Another study96 found that cigarette prices were temporarily reduced during post-MSA price wars prompted by market entry of lower-price firms responding to MSA-related price increases. Prices subsequently returned to a level consistent with market power by established firms.96 Suggestive of increased market power, stock returns of larger firms showed a decrease in systematic risk and in the cost of capital after the MSA.97

Beyond the specific effects from new legal requirements such as the FCLAA and MSA, new firms may also face entry barriers from the threat of civil lawsuits and legal liability from marketing addictive and harmful cigarettes.98 Although past lawsuits provide entrants with a roadmap of actions that may minimize liability risks, and entrants lack a past history of lawsuits that can be used against them, the larger, established firms have more resources and experience than new entrants to fight such lawsuits.

FIRM CONDUCT

In concentrated markets with high entry barriers, established firms may engage in anticompetitive pricing to increase their profits or to prevent market entry. To maximize profits, firms may engage in coordinated pricing through either explicit or tacit collusion.5 In addition, a dominant firm or coordinated group of firms can also temporarily reduce prices to discourage other firms, already in the industry or as entrants, from undercutting collusive prices.

With few firms, easily detectable price deviations, relatively homogeneous products, price insensitivity by consumers, and significant brand loyalty,21 the U.S. cigarette market is particularly vulnerable to coordinated pricing. The Supreme Court99 noted a lack of “significant price competition among rival firms […] List prices for cigarettes increased in lock-step twice a year, for a number of years.” An FTC Report100 also cited rising prices after 1980 and price wars following the entry of low price cigarette firms in 1991 as evidence of coordinated behavior among the major firms. The 1991 price wars began with Liggett & Myers selling generics.13 Following major price reductions for Marlboros (known as “Marlboro Friday”), industry concentration increased as smaller firms exited the industry and Marlboro’s market share increased beyond that which it had lost to generics.101

Economic studies have directly examined cigarette industry pricing, market share and revenue. One102 was unable to reject the hypothesis of competitive pricing from 1982–1995, and another72 found unstable firm market shares from 1934–94 as indicative of competitive behavior. However, other studies have found evidence of monopoly power from 1961–97 based on inter-state variations in advertising and pricing policies,103 and from 1962–92 based on pricing relative to cost.104 A study found interrelated firm advertising and pricing behavior from 1971–82, consistent with collusive behavior.79 The interrelated nature of firms’ advertising decisions was confirmed in a study spanning 1955–63.105

As a gauge of market power, economic studies have also examined the extent to which firms pass on tax increases in the form of cigarette prices. One early study found close to competitive price increases from 1954–78.106 Studies of more recent time periods, however, found price increases consistent with monopolistic pricing, with prices increasing by more than cigarette tax increases from 1960–1990,17 price increases doubling the amount of a 1984 tax increase,107 and post-MSA price increases exceeding federal and state tax increases and the per-pack costs from the MSA.108 Tax-price studies109,110 that considered coordinated pricing over various time periods found limited evidence of market power, but a later study74 incorporating advertising found a high degree of market power. Thus, even with increased cigarette taxes, cigarette companies have been able to raise their prices and minimize related reductions to their profits. Economic analysis has shown that companies can profitably increase prices more than the amount of a tax increase if demand becomes increasingly less responsive to price (ie, inelastic demand).111 This result may occur if price increases lead to a market with increasingly hard-core or otherwise price-insensitive smokers.111 However, companies can also profitably increase prices by more than a tax increase with declining demand.112 It is unclear the extent to which price increases reflect tax increases, declining demand or other contributing factors.

Another indication of anticompetitive behavior is price discrimination.113,114 With sufficient market power, firms can increase profits by reducing prices selectively to consumers who are most price sensitive, such as those with lower incomes or youth and young adults. At the same time, prices are increased to consumers who are less price sensitive, such as older, long-time smokers. Cigarette manufacturers engage in price discrimination through offering coupons that more price-sensitive consumers use to reduce price,115 price promotions and discounts in low income areas, and lower per-pack prices when purchased in cartons instead of individual packs.116 Price discrimination in the form of volume discounts and coupons has also been discussed in the tobacco control literature, with a particular focus on youth.117–120

DISCUSSION

Theoretical analyses and empirical evidence from the economics and marketing literature reveal substantial market power by the major firms in the US cigarette market. Market concentration has increased due to mergers, major-firm brand proliferation, and the growth of particular brands. In addition, entry barriers, especially retail slotting allowances and brand proliferation, have been substantial, and have protected market power. With high market concentration and entry barriers, the large, established firms have been able to engage in anticompetitive practices, such as collusive pricing, predatory price-cutting and price discrimination. We have focused on the economics and marketing literature, but the analysis may be supplemented with related legal literature and information gleaned from industry documents.

Standard economic and antitrust analysis disfavors market power and market concentration in favor of more active competition that will make products more readily available and affordable to consumers. However, market power in the cigarette market has benefited the public health to the extent that it has increased prices, thereby reducing smoking levels and related health outcomes. At the same time, increased market power has enabled the more established firms to target smaller firms by selectively reducing prices and proliferating brands, and to price discriminate by selectively reduce price to more price sensitive consumers. While these industry practices have been recognized in the public health literature,1–4 the emphasis appears to mainly relate to their impact on increasing profits, which is then channeled to lobby against potent tobacco control policies.

Although there are important differences between the economic/marketing and public health perspectives, the economic literature provides useful insights for tobacco control. For example, the FCLAA and the MSA have been found to enhance market power by acting to impede firm entry and entrench existing cigarette manufacturers. Neither the 1971 advertising restrictions nor the MSA constrained an important entry barrier, retail slotting allowances. Economic studies show the impacts of slotting allowances on market entry, prices, and retail advertising and promotions. These findings could be used to guide related new tobacco control regulations to promote public health (eg, by helping to reduce price promotions).

More generally, the economics literature could help to guide new tobacco control efforts to discourage market concentration and market power where it hurts the public health (eg, by increasing its ability to protect profits) and to encourage competition when it will produce new public health gains (eg, by shifting the market and smokers from cigarettes to less-harmful tobacco-nicotine products). These opportunities have expanded with the increasing use of non-cigarette nicotine delivery products.14–16,121 In particular, unlike earlier studies of cigarette demand, two recent studies34,122 indicate that consumers are highly responsive to both cigarette and e-cigarette prices, suggesting that the relevant market may have expanded beyond just cigarettes.

By 2003, the smokeless tobacco industry included few firms with major brands that had a strong reputation.123 Reynolds American acquired Conwood Smokeless Tobacco Company in 2006 and soon thereafter introduced Camel Snus, and Altria acquired the U.S. Smokeless Tobacco Company in 2009 and began marketing Marlboro Snus. Together they controlled 85% of the market.123 Industry documents124 indicate that the companies also began promoting smokeless tobacco products as a way for smokers to satisfy nicotine cravings in places where smoking was banned.124,125 In addition, marketing expenditures, including price promotions,126 and the marketing of flavored products increased.127 However, regulations that limit information on differences in the relative risks of smokeless tobacco and cigarettes or that otherwise limit competition by non-cigarette firms may also reduce incentives for smokers to switch entirely to smokeless tobacco rather than dual use with cigarettes.

Although cigarette companies have gained dominance in the smokeless tobacco market through acquiring the major smokeless tobacco firms, their status is quite different in the market for e-cigarettes. The product is sold by many companies not just in mass market retail, but also through vape shops, internet and other retail.128 Major cigarette companies, despite acquisitions and their own e-cigarette product development, have not been able to gain significant market share in the vape shop or internet markets, much less the overall e-cigarette market, and have recently even been struggling to maintain their share of conventional retail sales.. While an in-depth analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, there appears to be major impediments to the major cigarette companies being able to dominate the e-cigarette market because of such factors as the diversity of products, including many geared specifically towards providing an alternative to cigarettes, and the substantial sales via the Internet and non-traditional retail (eg, vape shops), which resist major company control. FDA regulations and required prior review of all new or changed products and proposed product relative-risk claims under the 2009 Tobacco Control Act will heavily influence which firms survive and the manner in which they market their products.

Because of the recent ongoing market changes, it is especially important that tobacco control policy consider market structure, barriers to market entry, pricing and product innovation. A better understanding of these influences can help to identify new public health challenges and opportunities, and thereby develop more effective tobacco control strategies. In the past, market concentration and entry barriers dampened price competition and prevented new companies from entering the cigarette market, and the consequences for public health were mixed. Now, however, competition appears to have increased between cigarettes and alternative nicotine products, suggesting a broader market. Nevertheless, a high concentration of cigarette manufacturers in these markets may prevent independent firms from entering with less harmful and better alternatives to cigarettes, or allow cigarette companies to market their e-cigarettes and other non-smoked tobacco products in ways that sustain or increase overall tobacco use and harms. Much will depend on government regulation. To promote the public health, the tobacco control community should build on the insights from the economics literature and carefully consider the existing structures of the different, increasingly interrelated nicotine delivery markets, and consider the impact of potential regulations on those structures.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TOBACCO REGULATION

Since the 1960s, U.S. cigarette market concentration has increased primarily due to mergers and growth in the Marlboro brand. The market has high entry barriers, due to advertising, brand proliferation and slotting allowance contracts, which were encouraged by government regulations. The anticompetitive structure has led to higher prices beyond those from government tax increases, consistent with tobacco control aims, but which has further enriched the major cigarette companies, increasing their ability to influence policies. . With the increase in multiproduct use and the introduction of alternative nicotine delivery products, it will be especially important to consider the market structure of related markets and the role of the cigarette industry in shaping those markets through its ability to exercise market power.

Acknowledgements:

Funding was received by the authors from the National Cancer Institute under grant P01CA200512.

Footnotes

Human Subjects: This study is exempt from review, as this study used secondary data sources..

Conflict of Interests: FJC has served as an expert witness in litigation against the cigarette industry.

Contributor Information

David Levy, Cancer Prevention and Control, Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Georgetown University, Washington, DC;.

Frank Chaloupka, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois;.

Eric N. Lindblom, Tobacco Control and Food & Drug Law, O’Neill Institute for National & Global Health Law, Georgetown University Law Center, Washington, DC;.

David T. Sweanor, Faculty of Law, University of Ottawa, Canada;.

Richard J. O’Connor, Department of Health Behavior, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY;.

Ce Shang, Department of Pediatrics and Oklahoma Tobacco Research Center, Stephenson Cancer Center, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK;.

Ron Borland, Cancer Council Victoria, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia..

References

- 1.Aguinaga Bialous S, Peeters S. A brief overview of the tobacco industry in the last 20 years. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):92–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilmore AB. Understanding the vector in order to plan effective tobacco control policies: an analysis of contemporary tobacco industry materials. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):119–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilmore AB, McKee M. Moving East: how the transnational tobacco industry gained entry to the emerging markets of the former Soviet Union-part I: establishing cigarette imports. Tob Control. 2004;13(2):143–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilmore AB, Tavakoly B, Taylor G, Reed H. Understanding tobacco industry pricing strategy and whether it undermines tobacco tax policy: the example of the UK cigarette market. Addiction. 2013;108(7):1317–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission. Horizontal Merger Guidelines. Washington DC: DoJ and FTC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission. Non-horizontal Merger Guidelines. Washington DC: DoJ and FTC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trebilcock M, Winter RA, Collins P, Iacobucci EM. The Law and Economics of Canadian Competition Policy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carree M, Günster A, Schinkel MP. European Antitrust Policy 1957–2004: An Analysis of Commission Decisions. Review of Industrial Organization. 2008;36(2):97–131. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crane DA. Harmful Output in the Antiturst Domain: Lessons from the Tobacco Industry. Georgia Law Review. 2005;39(321–409). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tauras JA, Levy D, Chaloupka FJ, et al. Menthol and non-menthol smoking: the impact of prices and smoke-free air laws. Addiction. 2010;105 Suppl 1:115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United States v. American Tobacco Co, 221 106 (Supreme Court 1911).

- 12.American Tobacco Co. v. United States. 1946;328 U.S. 781 (No. 18).

- 13.Federal Trade Commission. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Holdings, Inc./British American Tobacco p.l.c. [File No. 041–0017]. 2003.

- 14.Sung HY, Wang Y, Yao T, Lightwood J, Max W. Polytobacco Use of Cigarettes, Cigars, Chewing Tobacco, and Snuff Among US Adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):817–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health;2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasza KA, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, et al. Tobacco-Product Use by Adults and Youths in the United States in 2013 and 2014. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(4):342–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keeler TE, Hu TW, Barnett PG, Manning WG, Sung HY. Do cigarette producers price-discriminate by state? An empirical analysis of local cigarette pricing and taxation. J Health Econ. 1996;15(4):499–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallet CA. Advertising and Restrictions in the Cigarette Industry: Evidence of State-by-State Variation. Contemporary Economic Policy. 2003;21(3):338–348. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control. CDC State System. [Internet website]. 2017; http://nccd.cdc.gov/STATESystem/rdPage.aspx?rdReport=OSH_State.CustomReports&rdAgReset=True&rdShowModes=showResults&rdShowWait=true&rdPaging=Interactive. Accessed January 21, 2017.

- 20.Maxwell J Jr. The Maxwell Report. Richmond (VA): Maxwell John C. Jr.,;1963–2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Federal Trade Commission. Reynolds American Inc. and Lorillard Inc.; Analysis of Proposed Consent Order to Aid Public Comment [File No. 141–0168]. Federal Register. 2015;80(109). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan W The effects of taxes and advertising restrictions on the market structure of the US cigarette market. Review of Industrial Organization. 2006;28(3):231–251. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porter RH. The Impact of Government Policy on the US Cigarette Industry. Washington DC: Federal Trade Commission;1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24.United States. Federal Trade Commission. “Tar”, Nicotine, and Carbon Monoxide of the Smoke of 1294 Varieties of Domestic Cigarettes for the Year 1998. Washington, DC: United States. Federal Trade Commission;2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hviid M, Olczak M. Raising rivals’ fixed costs. International Journal of the Economics of Business. 2016;23(1):19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Comanor WS, Wilson TA. The effect of advertising on competition: A survey. Journal of economic literature. 1979;17(2):453–476. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chapter Bagwell K. 28: The Economic Analysis of Advertising In: Porter MA, ed. Handbook of Industrial Organization. Vol 3 Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown RS. Estimating advantages to large-scale advertising. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 1978:428–437. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peles Y Economies of scale in advertising beer and cigarettes. The Journal of Business. 1971;44(1):32–37. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmalensee R The economics of advertising. Vol 80: North-Holland Pub. Co; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas LG. Advertising in Consumer Goods Industries: Durability, Economies of Scale, and Heterogeneity. The Journal of Law & Economics. 1989;32(1):163–193. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Telser LG. Advertising and cigarettes. Journal of Political Economy. 1962;70(5, Part 1):471–499. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leone RP. Generalizing What is Known about Temporal Aggregation and Advertising Carryover. Marketing Science. 1995;14(3):G141–G150. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng Y, Zhen C, J. N, Dench D. Advertising, Habit Formation, and US Tobacco Product Demand. Am J of Agric Econ. 2016;98(4):1038–1054. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Capella ML, Webster C, Kinard BR. A review of the effect of cigarette advertising. International Journal of Research in Marketing. 2011;28(3):269–279. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dawes J Cigarette brand loyalty and purchase patterns: An examination using US consumer panel data. Journal of Business Research. 2014;67:1933–1943. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horsky D Market Share Response to Advertising: An Example of Theory Testing. Journal of Marketing Research. 1977;14(1):10–21. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iwasaki N, Kudo Y, Tremblay CH, Tremblay VJ. The advertising–price relationship: Theory and evidence. International Journal of the Economics of Business. 2008;15(2):149–167. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elzinga KG, Mills DE. Switching costs in the wholesale distribution of cigarettes. Southern Economic Journal. 1998:282–293. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cornelius ME, Cummings KM, Fong GT, et al. The prevalence of brand switching among adult smokers in the USA, 2006–2011: findings from the ITC US surveys. Tob Control. 2015;24(6):609–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siegel M, Nelson DE, Peddicord JP, Merritt RK, Giovino GA, Eriksen MP. The extent of cigarette brand and company switching: results from the Adult Use-of-Tobacco Survey. Am J Prev Med. 1996;12(1):14–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pollay R, Siddarth S, Siegel M, et al. The last straw? Cigarette advertising and realized market shares among youths and adults. Journal of Marketing. 1996;60(2):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmalensee R Entry deterrence in the ready-to-eat breakfast cereal industry. Antitrust L & Econ. 1979;10:319. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mainkar AV, Lubatkin M, Schulze WS. Toward a product-proliferation theory of entry barriers. Academy of Management Review. 2006;31(4):1062–1075. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krystallis A Uncovering attribute‐based determinants of loyalty in cigarette brands. Journal of Product & Brand Management. 2013;22(2):104–117. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tremblay VJ, Polasky S. Advertising with subjective horizontal and vertical product differentiation. Review of Industrial Organization. 2002;20(3):253–265. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reddy SK, Holak SL, Bhat S. . To Extend or Not to Extend: Success Determinants of Brand Line Extensions. Journal of Marketing Research. 1994;31(2):243–262. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simonich WL. Government antismoking policies. Lang P; 1991.

- 49.Holak SL, Tang YE. Advertising’s Effect on the Product Evolutionary Cycle. Journal of Marketing. 1990;54(3):16–29. [Google Scholar]

- 50.US Federal Trade Commission. Cigarette Report for 2014. 2016. Accessed March 7, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bloom PN, Gundlach GT, Cannon JP. Slotting Allowances and Fees: Schools of Thought and the Views of Practicing Managers. Journal of Marketing. 2000;64(2):92–108. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wright JD. Antitrust Analysis of Category Management: Conwood v United States Tobacco Co. Supreme Court Economic Review. 2009;17(1):311–337. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Innes R, Hamilton SF. Naked slotting fees for vertical control of multi-product retail markets. International Journal of Industrial Organization. 2006;24(2):303–318. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bronsteen P, Elzinga KG, Mills DE. Price competition and slotting allowances. The Antitrust Bulletin. 2005;50(2):267–284. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marx LM, Shaffer G. Opportunism in Multilateral Vertical Contracting: Nondiscrimination, Exclusivity, and Uniformity: Comment. American Economic Review. 2004;94(3):796–801. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang H Slotting allowances and retailer market power. Journal of Economic Studies. 2006;33(1):68–77. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marx LM, Shaffer G. Upfront payments and exclusion in downstream markets. The RAND Journal of Economics. 2007;38(3):823–843. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marx LM, Shaffer G. Slotting allowances and scarce shelf space. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy. 2010;19(3):575–603. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shaffer G Slotting allowances and optimal product variety. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy. 2005;5(1). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Achrol RS. Slotting allowances: a time series analysis of aggregate effects over three decades. Journal of the academy of marketing science. 2012;40(5):673–694. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Feighery EC, Ribisl KM, Achabal DD, Tyebjee T. Retail trade incentives: how tobacco industry practices compare with those of other industries. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(10):1564–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feighery EC, Ribisl KM, Clark PI, Haladjian HH. How tobacco companies ensure prime placement of their advertising and products in stores: interviews with retailers about tobacco company incentive programmes. Tob Control. 2003;12(2):184–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feighery EC, Ribisl KM, Schleicher NC, Clark PI. Retailer participation in cigarette company incentive programs is related to increased levels of cigarette advertising and cheaper cigarette prices in stores. Prev Med. 2004;38(6):876–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lariviere MA, Padmanabhan V. Slotting Allowances and New Product Introductions. Marketing Science. 1997;16(2):112–128. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Levy DT, Lindblom EN, Fleischer NL, et al. Public Health Effects of Restricting Retail Tobacco Product Displays and Ads. Tob Regul Sci. 2015;1(1):61–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frick RG, Klein EG, Ferketich AK, Wewers ME. Tobacco Advertising and Sales Practices in Licensed Retail Outlets After the Food and Drug Administration Regulations. J Community Health. 2012;37(5):963–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Balto D Recent legal and regulatory developments in slotting allowances and category management. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing. 2002;21(2):289–294. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moss D Antitrust Analysis of the Proposed Merger of R.J. Reynolds and British American Tobacco. 2004. Washington DC: American Enterprise Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tauras JA, Peck RM, F.J. C. The Role of Retail Prices and Promotions in Determining Cigarette Brand Market Shares. Review of Industrial Organization. 2006;28(3):253–284. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eckard EW. Competition and the cigarette TV advertising ban. Economic Inquiry. 1991;29(1):119–133. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eckard EW Jr. Advertising, competition, and market share instability. Journal of Business. 1987:539–552. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gallet CA, List JA. Market share instability: an application of unit root tests to the cigarette industry. Journal of Economics and Business. 2001;53(5):473–480. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mitchell ML, Mulherin JH. Finessing the political system: the cigarette advertising ban. Southern Economic Journal. 1988:855–862. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bihari S, Seldon B. The Effect of Government Advertising Policies on the Market Power of Cigarette Firms. Review of Industrial Organization. 2006;28(3):201–229. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Porter RH. The impact of government policy on the US cigarette industry. Empirical approaches to consumer protection economics. Washington DC: Federal Trade Commission; 1984:447–481. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Qi S The impact of advertising regulation on industry: The cigarette advertising ban of 1971. The RAND Journal of Economics. 2013;44(2):215–248. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Iwasaki N, Tremblay VJ. The effect of marketing regulations on efficiency: LeChatelier versus coordination effects. Journal of Productivity Analysis. 2009;32(1):41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schneider L, Klein B, Murphy KM. Governmental regulation of cigarette health information. The Journal of Law and Economics. 1981;24(3):575–612. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Roberts MJ, Samuelson L. An empirical analysis of dynamic, nonprice competition in an oligopolistic industry. The RAND Journal of Economics. 1988:200–220. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cowling K, McGuinness T, Cable J, Kelly M. Advertising and Economic Behavior. London: The Macmillan Press, Ltd.; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Baltagi B, Levin D. Estimating dynamic demand for cigarettes using panel data: The effects of bootlegging, taxation and advertising reconsidered. Review of Economics and Statistics. 1986;68:148–155. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hamilton JL. The demand for cigarettes: advertising, the health scare, and the cigarette advertising ban. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 1972:401–411. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schnabel M An oligopoly model of the cigarette industry. Southern Economic Journal. 1972:325–335. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Alemson MA. Advertising and the Nature of Competition in Oligopoly Over Time: A Case Study The Economic Journal. 1970;80(318):282–306. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Andrews R, Franke G. The determinants of cigarette consumption: A meta analysis. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing. 1991;10:81–100. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schneider L, Klein B, Murphy K. Governmental Regulation of Cigarette Health Information. Journal of Law and Economics. 1981;24(3):581. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Solow J Exorcising the Ghost of Cigarette Advertising Past: Collusion, Regulation, and Fear Advertising. Journal of Macromarketing. 2001;21(2):135–145. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Saffer H, Chaloupka F. The effect of tobacco advertising bans on tobacco consumption. J Health Econ. 2000;19(6):1117–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Blecher E The impact of tobacco advertising bans on consumption in developing countries. J Health Econ. 2008;27(4):930–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.U.S. National Cancer Institute and World Health Organization. The Economics of Tobacco and Tobacco Control. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute;2016. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Capella M, Taylor C, Webster C. The Effect Of Cigarette Advertising Bans On Consumption; A Meta-analysis. J Advertising. 2008;37(2):7–18. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lancaster K, Lancaster A. The economics of tobacco advertising: spending, demand, and the effects of bans. Int J Adv. 2003;22:41–65. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sloan FA, Mathews CA, Trogdon JG. Impacts of the Master Settlement Agreement on the tobacco industry. Tob Control. 2004;13(4):356–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fowler SJ, Ford WF. Has a quarter-trillion-dollar settlement helped the tobacco industry? J Econ and Fin. 2004;28(3):430–444. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Viscusi WK, Hersch J. Tobacco regulation through litigation: the Master Settlement Agreement Regulation vs. Litigation: Perspectives from Economics and Law: University of Chicago Press; 2010:71–101. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ciliberto F, Kuminoff V. Public Policy and Market Competition: How the Master Settlement Agreement Changed the Cigarette Industry. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy. 2010;10(1):Article 63. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sloan FA, Trogdon JG, Mathews CA. Litigation and the value of tobacco companies. J Health Econ. 2005;24(3):427–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Beneish M, Jansen I, Lewis M, Stuart N. Diversification to mitigate expropriation in the tobacco industry. J Financial Econ. 2008;89(1):136–157. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Brooke Group Ltd. V. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp; 509 U.S. 209, 213 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 100.United States. Federal Trade Commission. Competition and the financial impact of the proposed tobacco industry settlement. Washington, DC: The Commission; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chen T, Sun B, Singh V. An empirical investigation of the dynamic effect of Marlboro’s permanent pricing shift. Marketing Science. 2009;28(4):740–758. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Adhikari DR. Measuring market power of the US cigarette industry. Applied Economics Letters. 2004;11(15):957–959. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gallet CA. Advertising and Restrictions in the Cigarette Industry: Evidence of State‐by‐State Variation. Contemporary Economic Policy. 2003;21(3):338–348. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Arnade C, Pick D, Gopinath M. Testing oligopoly power in domestic and export markets. Applied Economics. 1998;30(6):753–760. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Seldon BJ, Banerjee S, Boyd RG. Advertising conjectures and the nature of advertising competition in an oligopoly. Managerial and Decision Economics. 1993;14(6):489–498. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sumner DA. Measurement of monopoly behaviour: An application to the cigarette industry, Journal of Political Economy. 1981;89(6):1010–1019. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Harris JE. The 1983 increase in the federal cigarette excise tax. Tax policy and the economy. 1987;1:87–111. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lillard DR, Sfekas A. Just passing through: the effect of the Master Settlement Agreement on estimated cigarette tax price pass-through. Applied economics letters. 2013;20(4):353–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sullivan D Testing hypothesis about firm behaviour in the cigarette industry. Journal of Political Economy. 1985;93(3):586–598. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ashenfelter O, Sullivan D. Nonparametric Tests of Market Structure: An Application to the Cigarette Industry. Journal of Industrial Economics. 1987;35(4):483–498. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yang C, Cheng H, Chi C, Huang B. A Tax Can Increase Profit of a Monopolist or a Monopoly-like Firm: A Fiction or Distinct Possibility? Hacienda publica espanola-review of public economics. 2016;216(1):39–60. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yang C, Trumbull W, Cushing B, Hwang M. Do Price Increases While Demand Is Falling Indicate Collusion? Journal of Competition Law & Economics. 2011;7(2):481–495. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chaloupka FJ, Cummings KM, Morley CP, Horan JK. Tax, price and cigarette smoking: evidence from the tobacco documents and implications for tobacco company marketing strategies. Tob Control. 2002;11 Suppl 1:I62–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chaloupka FJ, Straif K, Leon ME, Working Group IAfRoC. Effectiveness of tax and price policies in tobacco control. Tob Control. 2011;20(3):235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lillard DR, Sfekas A. Coupons and advertising in markets for addictive goods: do cigarette manufacturers react to known future tax increases? Substance Use: Individual Behaviour, Social Interactions, Markets and Politics: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2005:313–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.DeCicca P, Kenkel D, Liu F. Who pays cigarette taxes? The impact of consumer price search. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2013;95(2):516–529. [Google Scholar]

- 117.White VM, White MM, Freeman K, Gilpin EA, Pierce JP. Cigarette promotional offers: who takes advantage? Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(3):225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Brock B, Schillo BA, Moilanen M. Tobacco industry marketing: an analysis of direct mail coupons and giveaways. Tob Control. 2015;24(5):505–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Caraballo RS, Wang X, Xu X. Can you refuse these discounts? An evaluation of the use and price discount impact of price-related promotions among US adult smokers by cigarette manufacturers. BMJ Open. 2014;4(6):e004685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Brown-Johnson CG, England LJ, Glantz SA, Ling PM. Tobacco industry marketing to low socioeconomic status women in the U.S.A. Tob Control. 2014;23(e2):e139–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lee YO, Hebert CJ, Nonnemaker JM, Kim AE. Multiple tobacco product use among adults in the United States: cigarettes, cigars, electronic cigarettes, hookah, smokeless tobacco, and snus. Prev Med. 2014;62:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zheng Y, Zhen C, Dench D, Nonnemaker JM. U.S. Demand for Tobacco Products in a System Framework. Health Econ. 2017;26(8):1067–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.National Cancer Institute and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Report on Smokeless Tobacco and Public Health: A Global Perspective. Washington, DC: National Cancer Institute and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2014. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Carpenter CM, Connolly GN, Ayo-Yusuf OA, Wayne GF. Developing smokeless tobacco products for smokers: an examination of tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2009;18(1):54–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mejia AB, Ling PM. Tobacco industry consumer research on smokeless tobacco users and product development. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(1):78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Richardson A, Ganz O, Stalgaitis C, Abrams D, Vallone D. Noncombustible tobacco product advertising: how companies are selling the new face of tobacco. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(5):606–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Oliver AJ, Jensen JA, Vogel RI, Anderson AJ, Hatsukami DK. Flavored and nonflavored smokeless tobacco products: rate, pattern of use, and effects. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(1):88–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults A Report of the Surgeon General. . Atlanta, GA:: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]