Abstract

Neonatal ICU (NICU) hospitalizations provide opportunities to engage individuals/families who smoke with evidence-based cessation treatments to protect infants from tobacco smoke exposure. The aim of this pilot study was to establish the feasibility and potential efficacy of providing motivational advice and NRT (MA+NRT) to families of NICU infants. RCT methodology equally allocated participants who reported ≥1 household smoker (N=32) from a large NICU to MA+NRT or referral to a Quitline. The primary outcome was accepting NRT patches (MA+NRT) and use of NRT. Bayesian analyses modeled NRT use as a function of treatment group. Most MA+NRT participants (81.3%; n=13) accepted the patches. No Quitline participants called the Quitline. NRT use differed across groups, indicating a 0.907 posterior probability that a positive effect for MA+NRT exists (RR=2.32, 95% CI=[0.68–11.34]). This study demonstrated feasibility and acceptability for offering NRT and motivational advice to NICU parents and supports further intervention refinement with NICU families.

Keywords: smoking cessation, behavioral intervention, NICU, NRT, nicotine replacement therapy

1. Introduction

The health consequences associated with tobacco smoke exposure (TSE) during childhood are well-documented (USDHHS, 2007, 2014) and may pose the greatest risk to medically vulnerable infants, especially infants with underdeveloped respiratory systems (DiFranza et al., 2004; Halterman et al., 2008) Infants hospitalized in a neonatal ICU (NICU) often stay in the hospital for weeks or months (Northrup et al., 2016), thus providing an opportune window to engage parents who smoke (and may have heightened concerns about their child’s health) with evidence-based smoking cessation treatments (Forest, 2009; Stotts et al., 2013a; Stotts et al., 2013b). NICU staff are well positioned to deliver such intervention(Forest, 2009); however, a recent survey of 20 tertiary NICUs found that only 20% of NICUs reported routinely asking and offering support related to smoking, and less than half (47%) reported offering any advice about smoking at discharge (Nichols et al., 2019).

Smoking cessation by a single household member has limited benefit on TSE reduction when other family members continue to smoke in the home or around the child (Rosen et al., 2014), yet most child-TSE studies address maternal smoking only. This limitation is important, as our data show poorer infant TSE outcomes among mothers who perceived an inability to restrict all sources of TSE, compared to mothers who were confident they could. Only one child-focused TSE-reduction study provided behavioral and pharmacological support (i.e., NRT) for other adult smokers in the household (Ratschen et al., 2018). In another intervention study, fathers were provided separate telephone counseling (Baheiraei et al., 2011) which resulted in significant reductions in infant-urine cotinine. This study had one of the largest effect sizes in a meta-analytic review (Rosen et al., 2014). Significant potential to improve intervention outcomes by engaging additional household members who smoke may exist. Additionally, NICU families are often young and lack financial resources (Stotts et al., 2013a). Proactive interventions delivered to socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals suggest the provision of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and/or counselling may have significant benefit over usual care for decreasing adult smoking (Fu et al., 2016; Ratschen et al., 2018) and child TSE (Collins et al., 2015; Ratschen et al., 2018).

The primary aim of this pilot study was to establish the feasibility of providing either free motivational advice and NRT (MA+NRT) or tobacco-cessation Quitline referral to mothers of NICU infants and their partners and other household smokers, regardless of motivation to quit smoking. Several recent studies have found that providing NRT to unmotivated smokers who are not currently planning to quit was associated with positive smoking outcomes (Carpenter et al., 2011; Jardin et al., 2014). We hypothesized that providing MA+NRT or Quitline would be acceptable and feasible to NICU families and that higher use of the patch, quit attempts and smoking cessation would be demonstrated in the MA+NRT condition.

2. Methods

This pilot study used a parallel-group, randomized controlled design. Eligible participants who completed a baseline interview were randomized to either brief motivational advice plus nicotine replacement therapy (MA+NRT) or Quitline referral (1:1 ratio). The first author constructed the randomization sequence and informed the RA about condition assignment. Randomization was performed via a password-protected spreadsheet constructed with random number generation software (random.org) (with study allocation obscured by blacking out cells until the time of randomization [further, the RA did not know the password]). Institutional review boards of the university and hospital approved the protocol (HSC-MS-11–0641). This open-label study and protocol are registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04045964). All participants provided written, informed consent.

Participants (predominantly mothers) with an infant admitted to a NICU were recruited over a 7-month period (beginning in late October 2017) from a large children’s hospital in Houston, TX, until the enrollment target was reached. Eligibility criteria were: have a hospitalized NICU infant ≥1 week prior to the estimated hospital discharge date; report a household resident who smokes ≥5 cigarettes/day; agree to attend intervention sessions; and, have telephone access. Participants were ineligible if they had severe cognitive, and/or psychiatric impairment; were unable read, write, or speak English; or, were unwilling to meet study requirements. Current NRT use or contraindications (e.g., uncontrolled hypertension) also excluded participants.

MA+NRT participants were provided with either 2 weeks of 14-mg or 21-mg transdermal patches for every smoker in the home and received two in-hospital motivational advice sessions by a research associate (RA). The RA adapted session content from a previous TSE protocol(Stotts et al., 2013b). Quitline participants received information about TSE reduction (e.g., a smoking fact sheet about the harms of TSE) and a referral to a tobacco Quitline. Partners and other household members who currently smoked were invited to sessions.

All participants completed baseline assessment visits (in the hospital) and two follow-up assessment visits at the hospital or by phone at 2 weeks (F1) and 1-month post intervention (F2), which included sociodemographic- and smoking-related questions and a Timeline-Followback Interview (Sobell and Sobell, 1992) modified to assess NRT usage and smoking by all household smokers. Plans to quit in the next 30 days, 24-hour quit attempts, readiness-to-quit, readiness-to-use NRT, and home/car smoking bans (Stotts et al., 2013a; Stotts et al., 2013b) were assessed as secondary outcomes. We measured readiness-to-quit smoking or use NRT patches using an 11-point Contemplation Ladder, ranging from 0=“Not at all ready” to 10=“Extremely ready” (Stotts et al., 2019). Accepting NRT patches from the RA (for MA+NRT) and use of an NRT patch by any household smoker were primary outcomes.

Bayesian analyses modeled NRT use by any household smoker as a function of treatment group. In this initial pilot trial, we estimated a priori that 66.7% of MA+NRT and 33.3% of Quitline participants would use at least one patch, based on discussions with the investigative team. A sample size of 32 provided 80% power to detect this difference (alpha=0.05). Conventional frequentist statistical approaches of investigating small yet potentially meaningful effects may fail to reject the null hypothesis and provide only limited information for clinician decision-making. Even with modest effects or sample sizes, Bayesian analysis evaluates evidence from behavioral interventions well(Goligher et al., 2018; Laptook et al., 2017) (see examples/interpretive details in (Schmitz et al., 2017)). To estimate relative risk for the effect of treatment, vague, neutral priors were used for the regression coefficients (~Normal[0,100]) and the dichotomous outcome was modeled via the binomial distribution with a log link function. Bayesian analyses were performed in SAS v9.4 (PROC GENMOD; Cary, NC). Other data were reported descriptively due to small sample sizes.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

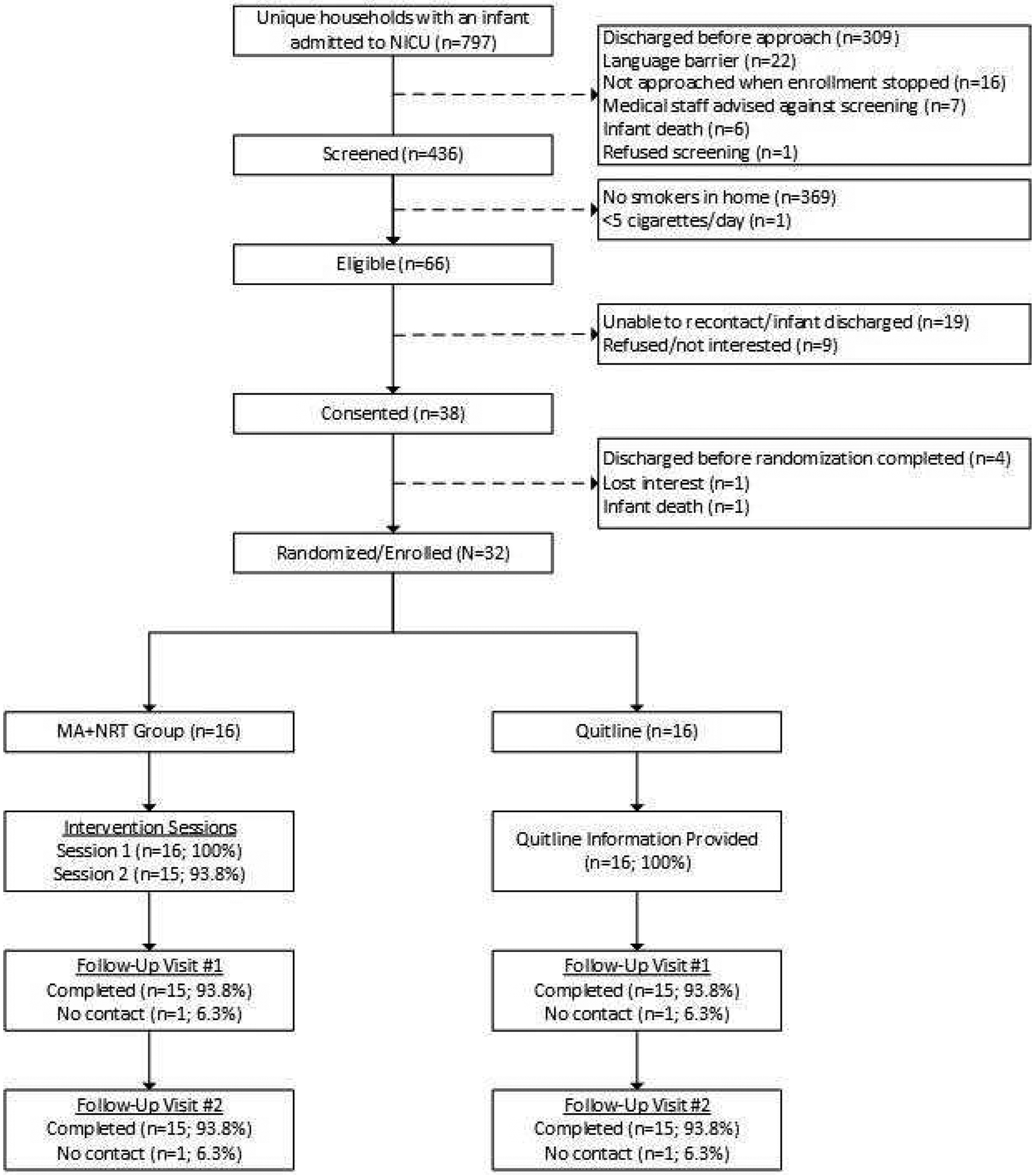

The RA screened over four hundred and thirty parents and sixty-six met the inclusion criteria (see Figure 1). Reasons for not consenting included: infant discharged prior to consent/randomization (n=19) and parent refusal (n=9). Of those who consented (n=38), four had their infant discharged, one lost interest, and one infant died before randomization, resulting in a sample size of 32 randomized participants (n=16 MA+NRT; n=16 Quitline). Most participants were mothers, belonged to a racial/ethnic minority and reported being married or living with a partner, receiving Medicaid, and being a nonsmoker (84.4%; n=27). No e-cigarette use was reported (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Screening, Enrollment, and Follow-Up Completion Flowchart

Table 1.

Participant and household characteristics at baseline visit

| Characteristic | MA + NRT | Quitline Referral |

|---|---|---|

| N | 16 | 16 |

| Female, n(%) | 15(93.8%) | 16(100%) |

| Race/ethnicity, n(%) | ||

| Black/African-American | 9 (56.3%) | 9 (56.3%) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 3(18.8%) | 4 (25.0%) |

| Hispanic | 3(18.8%) | 2(12.5%) |

| Asian | 1 (6.3% | 1 (6.3% |

| Report having a partner, n (%) | 14(87.5%) | 14(87.5%) |

| Married or living witn partner, n(%) | 12 (75.0%) | 11 (68.8%) |

| Annual household income <$25,000, n(%)A | 5 (31.3%) | 6 (42.9%) |

| Medicaid recipient, n(%) | 14(87.5%) | 13(81.3%) |

| Age (Years), M(SD) | 30.6 (9.7) | 29.9 (4.3) |

| Currently working, n(%)B | 3(18.8%) | 3(18.8%) |

| Number of children in home, M(SD) | 2.7(1.5) | 3.6 (2.7) |

| Number of adults in home, M(SD) | 2.8(1.1) | 2.3 (0.8) |

| Years of education, M(SD) | 13.1 (1.4) | 13.0(2.2) |

| Pregnancy unplanned, n(%) | 10(66.7%) | 11 (68.8%) |

| Number of pregnancies | 3.0 (2.0) | 3.8 (2.7) |

| Smoking history (participant), n(%) | ||

| Current smoking | 2(12.5%) | 3(18.8%) |

| Quit (during pregnancy) | 0 (0%) | 2(12.3%) |

| Quit (before pregnancy) | 5 (31.3%) | 2(12.3%) |

| Never smoked | 9 (56.3%) | 9 (56.3%) |

| <10 cigarettes/day (participant), n(%) | 2(100%) | 2 (66.7%) |

| Current smoking (partner)C | 12(85.7%) | 12(85.7%) |

| <10 cigarettes/day (partner), n(%) | 6 (50.0%) | 7 (58.3%) |

| Current smoking (other household member)C | 7 (43.8%) | 6 (37.5%) |

| <10 cigarettes/day (other household member), n(%) | 5 (71.4%) | 3 (50.0%) |

| Two or more smokers in home, n(%) | 4 (25.0%) | 5 (31.3%) |

Note. Where numbers do not add up to 16 (within condition), the remainder represent missing data.

Two participants did not know their household income and did not report it.

One participant reported working part-time and remainder reported full-time work.

Four participants (two in each condition) did not have a current partner.

3.2. MA+NRT and Quitline Attendance

MA+NRT intervention visit attendance was high, with 93.8% (n=15) of participants attending both visits. Other household members attended 44.8% (n=7) of session-one visits and 18.8% (n=3) of session-two visits. Across both MA+NRT sessions, a household smoker was present at 22.6% of sessions (n=6 session one; n=1 session two). The MA+NRT counselor reported that 81.2% (n=13) of attendees participated, “A great deal” or “Extremely” at MA+NRT session one, which declined to 40.0% (n=6) at session two.

All Quitline participants received TSE education and the phone number to the state Quitline. Of Quitline visits, 44.8% (n=7) were attended by participants’ partners and/or other household members and a household smoker was present at 25% (n=4) of visits.

3.3. NRT Patch Acceptance and Quitline Calls

Of MA+NRT mothers, 81.3% (n=13) accepted the nicotine patches from the RA for themselves, partners, or other household members. None of the Quitline participants (mothers) reported calling the Quitline, nor did their partners or other household members.

3.4. Overall Household Outcomes

The proportion of MA+NRT households where at least one household smoker initiated NRT was greater (37.5%, n=6) compared to the Quitline households (12.5%, n=2). Bayesian generalized linear modeling evaluated any NRT use in the home as a function of treatment, finding a 0.907 posterior probability that a positive effect of treatment exists. The MA+NRT were 2.3 times as likely to engage in any NRT use compared to Quitline (RR=2.32, 95% CI=[0.68–11.34]). Across groups, the number of homes with two or more smokers declined over the course of the study, with over 20% of homes reporting no smoking by the final time point, which was associated with smokers moving out of the home (or the participant moving homes) or the smoker quitting (Table 2). Self-reported home bans (on indoor smoking) and car-smoking bans were relatively high at baseline and rose further by the final study visit.

Table 2.

Smoking, e-cigarette, and NRT outcomes by condition and time point

| Outcome Measures | MA + NRT | Quitline Referral | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment Visit | Assessment Visit | |||||

| Participant Outcomes | Baseline | F1 | F2 | Baseline | F1 | F2 |

| Current smokinq, n(%) | 2 (12.5%) | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (18.8%) | 4 (26.7%) | 3 (20.0%) |

| E-cigarette use, n(%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Planning to Quit in next 30 days, n(%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | 2 (66.7%) | 3 (75.0%) | 3(100%) |

| Readiness to quit, M(SD) | 5.0 (2.8) | 7.0 (2.8) | 10.0 (.) | 6.3 (4.7) | 8 (2.2) | 7.5 (4.4) |

| Readiness to use NRT patches, M(SD) | 3.0 (2.8) | 4.0 (4.2) | 1.0 (.) | 5.0 (4.0) | 3.3 (4.5) | 3.3 (4.5) |

| Initiated NRT, n(%) | - | 1 (50%)B | 1 (100%)B | - | 2 (66.7%)B | 2 (50.0%)B |

| Participants with ≥1 quit attempt(s), n(%) | 1 (50.0%)A | 2 (100.0%)B | 1 (100.0%)B | 1 (33.3%)A | 1 (33.3%)B | 4(100.0%)B |

| Partner OutcomesC | ||||||

| Current smokinq, n(%) | 12(85.7%) | 9 (75.0%) | 7 (70.0%) | 12 (85.7%) | 11 (91.7%) | 9 (75.0%) |

| E-ciqarette use, n(%) | 2(14.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (10.0%) | 1 (7.1%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Readiness to quit, M(SD) | 4.5 (3.5) | 3.7 (2.6) | 4.7 (2.8) | 5.0 (3.7) | 5.3 (2.8) | 6.7 (3.5) |

| Readiness to use NRT patches, M(SD) | 3.8 (3.2) | 3.1 (2.7) | 3.4 (3.5) | 3.4 (3.3) | 4.0 (3.5) | 2.8 (3.0) |

| Initiated NRT, n(%) | - | 3 (25.0%)B | 3 (33.3%)B | - | 1 (8.3%)B | 1 (9.1 %)B |

| Partners with a ≥1 quit attempts, n(%) | - | 5(41.7%)B | 2 (22.2%)B | - | 0 (0%)B | 1 (9.1 %)B |

| Other Household Member OutcomesC | ||||||

| Current smoking, n(%) | 7 (43.8%) | 5 (33.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 6 (37.5%) | 2(13.3%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| E-cigarette use, n(%) | 1 (14.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Readiness to quit, M(SD) | 2.9(1.6) | 4.0 (1.7) | 3.2 (2.0) | 7.2 (3.7) | 6.5 (0.7) | 9.0 (.) |

| Readiness to use NRT patches, M(SD) | 2.1 (2.0) | 2.4(3.1) | 1.8(1.8) | 6.6 (3.7) | 9.0(1.4) | 7.0 (.) |

| Initiated NRT, n(%) | - | 2 (28.6%) | 2 (40.0%)B | - | 0 (0%)B | 0 (0%)B |

| Others with a ≥1 quit attempts, n(%) | - | 0 (0%)B | 0 (0%)B | - | 0 (0%)B | 0 (0%)B |

| Household Outcomes | ||||||

| Any NRT use by household, n(%) | - | 6 (37.5%) | 6 (37.5%) | - | 2 (12.5%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| Two or more smokers in home, n(%) | 4 (25.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | 2 (13.3%) | 5 (31.3%) | 3 (20.0%) | 2(13.3%) |

| Zero smokers in home (due to quitting), n(%) | - | 1 (6.3%) | 2 (12.5%) | - | 0 (0%) | 1 (6.3%) |

| Ban smoking indoors (at home), n(%) | 14 (87.5%) | 14 (93.3%) | 14 (93.3%) | 10 (62.5%) | 13 (86.7%) | 14 (93.3%) |

| Ban smoking inside of cars, n(%) | 11 (68.8%) | 14 (93.3%) | 14 (93.3%) | 10 (66.7%)D | 12 (80.0%) | 14 (93.3%) |

Note. F1=2-week follow-up visit; F2=1-month follow-up visit. MA+NRT and Quitline groups each had one participant missing from F1 and F2 follow-up visits and neither of the missing participants reported maternal baseline smoking. “ - “ indicates a variable was not assessed at this time point.

Quit attempts during pregnancy and up to the baseline visit were assessed at baseline.

NRT initiation and quit attempts since the previous visit were assessed at F1 (i.e., since baseline visit) and F2 (i.e., since F1 visit). The number of current smokers from the previous visit was used as the denominator for calculating percentages at F1 and F2 visits.

Four participants (two in each condition) reported not having a current partner at baseline, six participants (three in each condition) reported not having a partner at the F1 visit, and eight reported not having a partner at F2 (five in the MC+NRT condition; three in the Quitline condition). Percentages were calculated based on participants who reported current partners.

One participant in the Quitline condition failed to answer this question.

3.5. Participant (Mothers) Outcomes

Thirty (out of 32 participants; 93.8%) completed both follow-up visit one and two (F1, F2). The five mothers who reported current smoking at baseline (n=2 MA+NRT; n=3 Quitline; Table 1) tended to report relatively light smoking (i.e., <10 cigarettes/day (Husten, 2009)). At baseline, most participants reported low or moderate readiness-to-quit and readiness-to-use NRT patches. None of the MA+NRT participants, but two of the three Quitline participants, reported a plan to quit in the next 30 days. Readiness-to-quit generally increased from baseline to F1 and F2 (for both groups) and readiness-to-use NRT patches generally declined over time (see Table 2).

Most participants (in both groups) made at least one quit attempt (see Table 2). Reported smoking declined in the MA+NRT participants at F1 and F2 and increased for Quitline participants at F1 and remained stable at F2 (compared to baseline). Across conditions, three participants used NRT patches (n=1 MA+NRT; n=2 Quitline) on at least one day. One Quitline mother reported that she also obtained cessation medication. One MA+NRT participant (who initiated the patch) discontinued use due to skin irritation. Another MA+NRT participant reported she did not need patches to quit.

3.6. Partner Outcomes

A higher proportion of partners were current smokers and about half smoked <10 cigarettes/day (Table 1), with very few reportedly using e-cigarettes (Table 2). At baseline, most participants reported their partners were low to moderate on readiness-to-quit and readiness-to-use NRT patches. Partner readiness-to-quit and readiness-to-use NRT patches, as reported by participants, generally declined or remained unchanged from baseline to F1 and F2 in both groups (Table 2). Most participants reported that their partners did not attempt to quit smoking. However, MA+NRT participants reported more quit attempts by their partners than Quitline participants (Table 2).

Four partners initiated NRT patches (n=3 MA+NRT; n=1 Quitline). Noteworthy, two Quitline participants reported their partners obtained NRT but one partner did not initiate use. Also, one Quitline participant reported her partner obtained smoking cessation medication and another reported her partner used e-cigarettes for help quitting. Most MA+NRT participants reported that their partners did not use the patches due to: feeling like they did not need the NRT patches to quit (n=4, 44.4%), not wanting to quit smoking (n=2, 22.2%), never/no longer being interested in NRT to quit (n=3; 33.3%), or still planning to use NRT (n=2; 22.2%).

3.7. Other Household Member Outcomes

Across conditions, 40.6% of households (n=13) had someone other than the participant or partner engaging in smoking. Other household members who smoked were the infants’ grandparents (n=3 MA+NRT; n=6 Quitline) and other relatives (n=4 MA+NRT; n=0 Quitline). These individuals tended to smoke <10 cigarettes/day (Table 1). At baseline, MA+NRT participants reported low readiness-to-quit for other household smokers, while Quitline participants reported their other household members were higher in readiness-to-quit (Table 2). Similar patterns were found for readiness-to-use NRT patches, with MA+NRT participants reporting low readiness-to-use and Quitline participants reporting higher readiness-to-use NRT patches, among other household members. Readiness-to-quit and readiness-to-use NRT patches by other household members increased slightly or remained stable from baseline to F1 and F2 in both groups. Sample sizes for other household smokers at F1 and F2 were notably very small for Quitline participants (Table 2).

Of the other household members, two initiated NRT patches (n=2 MA+NRT; n=0 Quitline). Other household smokers reportedly discontinued/did not use the patches due to: feeling they did not need the NRT patches to quit (n=2, 40.0%), not wanting to quit smoking (n=1, 20.0%), never/no longer being interested in NRT to quit (n=2, 40.0%), forgetting about using NRT (n=1, 20.0%), and discontinuing use due to physical discomfort (n=2, 40.0%).

4. Discussion

NICUs are an underutilized environment for engaging young, socioeconomically disadvantaged parents who smoke or live with a household smoker. This study demonstrated feasibility for offering brief intervention and free NRT or referral to a Quitline. Both options were acceptable to NICU families, with a low proportion of refusals among eligible families. A greater proportion of MA+NRT homes had at least one smoker use the patches compared to the Quitline households.

Mothers and their family members engaged with the RA in discussing TSE protection for their infants and also accepted the nicotine patches at high rates, despite relatively low readiness-to-change. Indeed, smokers may not need to feel motivated to quit to engage in smoking cessation (Carpenter et al., 2011; Jardin et al., 2014). However, the use of patches was relatively low and readiness-to-use patches, as well as participation in MA+NRT sessions, declined with time indicating a need for intervention optimization. For example, some participants may have been too polite or felt too embarrassed to decline the patches and others may have felt inhibited to ask research staff follow-up questions about how to use the patches (indicating a knowledge gap). Bernstein et al. (Bernstein et al., 2015) reported success providing emergency-department patients who smoked with 6 weeks of free NRT (patch/gum) and administering the first dose in the ED, to remove initiation barriers and demonstrate rapid effects on nicotine-withdrawal symptoms. Addressing possible knowledge gaps and drops in readiness-to-change (for all household members), incentivizing intervention attendance as well as NRT use (with contingency management strategies) and utilizing behavioral health professionals to deliver intervention visits may also increase participation in treatment (Petry et al., 2006; Stotts et al., 2013b). Combination NRT (e.g., nicotine lozenges/gum + patch) often has greater efficacy than one NRT method alone and should be explored in the NICU environment. Creative methods by which to engage all household members with evidence-based smoking treatments could improve infant health outcomes attributed to chronic TSE exposure. Further, MA+NRT be an ideal smoking-cessation intervention for reengaging mothers who quit or refrained from smoking while pregnant and returned to smoking after infant delivery.

Follow-on studies will improve on the methods employed in this small pilot study. NRT use and smoking cessation was not biologically verified. Further, participants reported on partners’ and other household members’ smoking behaviors, rather than RAs asking them directly. Selection bias may have affected outcomes (e.g., participants being discharged before randomization due to limited research staff support) and an adequately staffed research team will mitigate this concern in future work. Finally, larger samples, designed to objectively measure intervention fidelity (e.g., NRT usage) and powered to detect cessation outcomes will determine whether the MA+NRT (or a variant) is efficacious.

Interest in evidence-based smoking cessation treatments is clearly high among this population of families caring for a medically fragile NICU infant. It is also clear that more education/assistance with initiating and maintaining NRT is needed. A large majority of MA+NRT participants accepted the study-provided NRT patches but many participants and other household smokers never attempted to use them. Engaging partners and addressing their NRT-related concerns while bolstering motivation for quitting is essential for successful NICU infant TSE reduction, as partners (fathers) comprise the overwhelming majority of smokers in these homes. Data from our study and others (Ratschen et al., 2018) indicate more intensive interventions are warranted. Interventions collectively targeting all household smokers will achieve greater uptake and reduce TSE exposure, sorely needed for medically vulnerable infants and other household children.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL107404; PI=A.L. Stotts) and National Institute on Drug Abuse (R34 DA041465; PI=A.L. Stotts) at the U.S. National Institutes of Health and Department of Health and Human Services. A portion of Dr. Northrup’s writing time was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (1R03HD088847; PI: T.F. Northrup) at the US National Institutes of Health and Department of Health and Human Services.

Acronyms and abbreviations:

- F1

2-week, post-intervention follow-up visit

- F2

1-month, post-intervention follow-up visit

- MA+NRT

brief motivational advice plus nicotine replacement therapy (experimental condition)

- NICU

neonatal intensive care unit

- NRT

nicotine replacement therapy

- RA

research associate

- TSE

tobacco smoke exposure

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Baheiraei A, Kharaghani R, Mohsenifar A, Kazemnejad A, Alikhani S, Milani HS, Mota A, Hovell MF, 2011. Reduction of secondhand smoke exposure among healthy infants in Iran: randomized controlled trial. Nicotine Tob. Res 13, 840–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein SL, D’Onofrio G, Rosner J, O’Malley S, Makuch R, Busch S, Pantalon MV, Toll B, 2015. Successful tobacco dependence treatment in low-income emergency department patients: a randomized trial. Ann. Emerg. Med 66, 140–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter MJ, Hughes JR, Gray KM, Wahlquist AE, Saladin ME, Alberg AJ, 2011. Nicotine therapy sampling to induce quit attempts among smokers unmotivated to quit: a randomized clinical trial. Arch. Intern. Med 171, 1901–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins BN, Nair US, Hovell MF, DiSantis KI, Jaffe K, Tolley NM, Wileyto EP, Audrain-McGovern J, 2015. Reducing Underserved Children’s Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Randomized Counseling Trial With Maternal Smokers. Am. J. Prev. Med [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Aligne CA, Weitzman M, 2004. Prenatal and postnatal environmental tobacco smoke exposure and children’s health. Pediatrics 113, 1007–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forest S, 2009. Preventing postpartum smoking relapse: An opportunity for neonatal nurses. Adv. Neonatal Care 9, 148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu SS, Van Ryn M, Nelson D, Burgess DJ, Thomas JL, Saul J, Clothier B, Nyman JA, Hammett P, Joseph AM, 2016. Proactive tobacco treatment offering free nicotine replacement therapy and telephone counselling for socioeconomically disadvantaged smokers: a randomised clinical trial. Thorax 71, 446–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goligher EC, Tomlinson G, Hajage D, Wijeysundera DN, Fan E, Juni P, Brodie D, Slutsky AS, Combes A, 2018. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and posterior probability of mortality benefit in a post hoc Bayesian analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 320, 2251–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halterman JS, Lynch K, Conn K, Hernandez T, Perry TT, Stevens T, 2008. Environmental exposures and respiratory morbidity among very low birth weight infants at one year of life. Arch. Dis. Child 94, 28–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husten CG, 2009. How should we define light or intermittent smoking? Does it matter? Nicotine Tob. Res 11, 111–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardin BF, Cropsey KL, Wahlquist AE, Gray KM, Silvestri GA, Cummings KM, Carpenter MJ, 2014. Evaluating the effect of access to free medication to quit smoking: a clinical trial testing the role of motivation. Nicotine Tob. Res 16, 992–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laptook AR, Shankaran S, Tyson JE, Munoz B, Bell EF, Goldberg RN, Parikh NA, Ambalavanan N, Pedroza C, Pappas A, 2017. Effect of therapeutic hypothermia initiated after 6 hours of age on death or disability among newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 318, 1550–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols A, Clarke P, Notley C, 2019. Parental smoking and support in the NICU. Archives of Disease in Childhood-Fetal and Neonatal Edition, fetalneonatal-2018–316413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northrup TF, Evans PW, Lillie ML, Tyson JE, 2016. A free parking trial to increase visitation and improve extremely low birth weight infant outcomes. J. Perinatol 36, 1112–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Carroll KM, Hanson T, MacKinnon S, Rounsaville B, Sierra S, 2006. Contingency management treatments: Reinforcing abstinence versus adherence with goal-related activities. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 74, 592–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratschen E, Thorley R, Jones L, Breton MO, Cook J, McNeill A, Britton J, Coleman T, Lewis S, 2018. A randomised controlled trial of a complex intervention to reduce children’s exposure to secondhand smoke in the home. Tob. Control 27, 155–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen LJ, Myers V, Hovell M, Zucker D, Noach MB, 2014. Meta-analysis of parental protection of children from tobacco smoke exposure. Pediatrics 133, 698–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JM, Green CE, Hasan KM, Vincent J, Suchting R, Weaver MF, Moeller FG, Narayana PA, Cunningham KA, Dineley KT, 2017. PPAR-gamma agonist pioglitazone modifies craving intensity and brain white matter integrity in patients with primary cocaine use disorder: a double-blind randomized controlled pilot trial. Addiction 112, 1861–1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, 1992. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption, in: Litten R, Allen J (Eds.), Measuring alcohol consumption. Humana Press, Inc, Totowa, NJ, pp. 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Stotts AL, Green C, Northrup TF, Dodrill C, Evans P, Tyson J, Velasquez M, Hammond K, Hovell M, 2013a.. Feasibility and efficacy of an intervention to reduce secondhand smoke exposure among infants discharged from a neonatal intensive care unit. J. Perinatol 33, 811–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotts AL, Northrup TF, Schmitz JM, Green C, Tyson J, Velasquez MM, Khan A, Hovell MF, 2013b. Baby’s Breath II protocol development and design: A secondhand smoke exposure prevention program targeting infants discharged from a neonatal intensive care unit. Contemp. Clin. Trials 35, 97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotts AL, Villarreal YR, Klawans MR, Suchting R, Dindo L, Dempsey A, Spellman M, Green C, Northrup TF, 2019. Psychological flexibility and depression in new mothers of medically vulnerable infants: A mediational analysis. Matern. Child Health J 23, 821–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS, 2007. Children and Secondhand Smoke Exposure: The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS, 2014. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress. A report of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]