Abstract

Introduction

In 2001, 50%–55% of French-speaking minority communities did not have access to health services in French in Canada. Although Canada is officially a bilingual country, reports indicate that many healthcare services offered in French in Anglophone provinces are insufficient or substandard, leading to healthcare discrepancies among Canada’s minority Francophone communities.

Objectives

The primary aim of this scoping systematic review was to identify existing gaps in HIV-care delivery to Francophone minorities living with HIV in Canada.

Study design

Scoping systematic review.

Data sources

Search for studies published between 1990 and November 2019 reporting on health and healthcare in Francophone populations in Canada. Nine databases were searched, including Medline, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, the Cochrane Library, the National Health Service Economic Development Database, Global Health, PsychInfo, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science.

Study selection

English or French language studies that include data on French-speaking people with HIV in an Anglophone majority Canadian province.

Results

The literature search resulted in 294 studies. A total of 230 studies were excluded after duplicates were removed. The full texts of 43 potentially relevant papers were retrieved for evaluation and data extraction. Forty-one studies were further excluded based on failure to meet the inclusion criteria leaving two qualitative studies that met our inclusion criteria. These two studies reported on barriers on access to specialised care by Francophone and highlighted difficulties experienced by healthcare professionals in providing quality healthcare to Francophone patients in Ontario and Manitoba.

Conclusion

The findings of this scoping systematic review highlight the need for more HIV research on linguistic minority communities and should inform health policymaking and HIV/AIDS community organisations in providing HIV care to Francophone immigrants and Canadians.

Keywords: HIV & AIDS, public health, health policy, epidemiology, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A strength of this study is that we have conducted a comprehensive and exhaustive search of peer-reviewed articles and grey literature on a research question that has never been addressed before.

Another strength of the study is that its findings highlight disparities in Canada’s healthcare systems and could be investigated in Francophone minority populations worldwide.

A limitation is that information on HIV care in Francophone African Caribbean and Black (ACB) populations was limited to two provinces: Ontario and Manitoba.

Another limitation is the small number of studies addressing HIV care deficiencies among Francophone ACBs, suggesting a lack of research on this population and making it difficult to estimate how these disparities manifest in provinces and territories outside of Ontario and Manitoba.

Introduction

In 2001, 50%–55% of French-speaking minority communities in Canada did not have access to health services in French.1 Therefore, in 2003, Health Canada launched the Official Languages Health Program with the aim of improving access to health services for official language minority communities. Continuity and accessibility to care is a problem in general healthcare and HIV care for Francophone communities in Canada.2–6 In Canada, the term Francophone refers to someone whose mother tongue or first official language spoken is French and who lives outside of the province of Quebec in a majority English-speaking province.7 8

Although Canada is officially a bilingual country, reports indicate that many healthcare services offered in French in Anglophone provinces are insufficient or substandard, leading to healthcare discrepancies among Canada’s minority Francophone communities.9–12 In 2005, shortages in medical interpreters, Francophone healthcare providers and services were noted in Winnipeg’s Francophone communities, making it difficult for patients to understand medical instructions and advice, find a general physician and access or be referred to specialised care.10

In Ontario, the French Language Service Act of 1986 (FLSA) guarantees the right of individuals to receive French language services, as well as French healthcare services, from the Ontario government ministries and agencies.13 However, French HIV resources, including Francophone health and social workers, have been described as lacking by Ontarian Francophone living with HIV. French-speaking professionals reported that French-service shortages across Ontario left them overworked as they took on interpreting and translating duties on top of their workloads.11 13

In addition, Ontarian healthcare professionals noted that Francophone patients receiving care in English are more vulnerable than their Anglophone counterparts, especially if the patient’s issues and needs are complex, such as those with complicated illnesses, vision and hearing deficiencies or mental illness. They also stated that these Francophone patients may not disclose important information about their health in English or disclose less information overall. This could be due to Francophone patients being unable to express themselves fully in English or being uncomfortable relaying information through an interpreter, especially if that interpreter is someone whom they are personally close to.11 12

This deficiency in Francophone health services is worrying, especially since Canada’s minority francophone population is increasing.7 14 In Ontario, roughly 5% of the population are Francophone, of which about 7.5% speak only French.14 The Francophone population in Canada is bolstered by immigration, including immigrants from French-speaking African and Caribbean countries.9 Hence, the healthcare needs of Canada’s Francophone population help illustrate the increasing demand for healthcare delivery in French.9–12 In 2016, the Public Health Agency of Canada reported that approximately one-third of people living with HIV (PLWH) in Ontario were from African Caribbean and Black (ACB) communities.15 Additionally, as reported by a study done in the USA, language, a social determinant of health, was one barrier hindering sub-Saharan African and Caribbean immigrants from being tested for HIV.16 While AIDS Service Organizations (ASOs) acknowledge the importance of bilingual healthcare, they also reported having to prioritise their resources into dealing with other issues plaguing HIV-positive communities, such as unsafe housing, food insecurity and mental illness.9

Even though the experience of African, Caribbean and Black PLWH has been studied before, in this scoping systematic review, we aimed to identify existing gaps in HIV care delivery to HIV-diagnosed Francophone ACB in Canada.17 Our secondary goal is to examine the condition of this population’s HIV care continuum (or cascade) by evaluating the information on health promotion, proximity to healthcare centres, quality of life, quality of care, effect of race, stigma and discrimination on care provided, availability of bilingual healthcare providers, preventive care and patient satisfaction.

Methods and analyses

We used scoping review methodology adopted from the framework described by Arksey and O’Malley.18 The protocol for this scoping review is reported elsewhere.8 Our methods are outlined below.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Search strategy for identification of studies

We conducted an exhaustive search for published studies in English or French reporting on health and healthcare in Francophone populations in Canada. The online search was restricted to articles published between 1990 (the date that the FLSA was implemented in Ontario, Canada) and November 2019.13

Nine databases, Medline, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, the Cochrane Library, the National Health Service Economic Development Database, Global Health, PsychInfo, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science, were searched. The population was defined using text and indexed words relating to immigration, combined with the names of all French-speaking countries in Africa and the Caribbean.8 Canada, as a location, was specified by searching the English and French names of all the provinces and territories, as well as their ministries of health. When combined, these sets were filtered to include any mention of HIV, seroconversion, seropositivity or sexually transmitted diseases. As an example some of the following terms in various combinations were used for the search: ‘Emigrants and Immigrants’ OR (French or francais or franco* or Quebec*’ OR ‘Africa* or African or Afrique or Africain*’ OR ‘Caribbean’ OR ‘Caribbean Region’ OR ‘Health Care Quality, Access/and Evaluation’ OR ‘Health Services Accessibility’ OR ‘HIV infections’ OR ‘Seropositivity/Seroconversion’ OR ‘Canada or Canad*’ OR ‘Black Canadian’ (see online supplementary file 1).

bmjopen-2020-036885supp001.pdf (41.1KB, pdf)

The search strategy is also reported in the published protocol.8

Grey literature

We searched the websites of relevant HIV organisations such as the African and Caribbean Council on HIV/AIDS in Ontario, Association Francophone pour le Savoir, The Ontario HIV Treatment Network and Canada's source for HIV and hepatitis C information. Furthermore, Health Canada’s and Francophone community organisations’ websites were also searched for literature.

Criteria for including studies

Types of studies

Experimental, observational, qualitative, mixed methods and studies focused on evidence syntheses were considered for review.

Types of participants

To be eligible, a study must have included data on French-speaking people with HIV in an Anglophone majority Canadian province. Studies from Quebec were excluded as Francophone are, by definition, French-speaking people living in English-speaking provinces in Canada.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes investigated, in this study, were access to healthcare and quality of care for Francophone living with or without HIV in Anglophone majority provinces. Access to HIV care included HIV diagnosis, linkage and retention to care, receipt of antiretroviral therapy, adherence to medication and achievement of viral suppression.

Other outcomes of interest were participation in health promotion, proximity to healthcare centres and access to bilingual healthcare providers and preventive care. Data were also extracted on the quality of care provided as well as the effect of race, stigma and discrimination on care provided as well as the quality of life and patient satisfaction.

Screening

All references retrieved were imported into Rayyan Qatar Computing Research Institute to facilitate study screening and selection.19 Duplicate studies were removed prior to undertaking the abstract review. Screening was done independently by JAO, COZ, JN and PD.

Our screening form was developed and applied independently to a sample of 50 abstracts to ensure consistency of use and clarity of the instrument. A Cohen’s κ statistic was used to measure inter-rater reliability, and screening started when >60% agreement was achieved.20

Data collection and analyses

Data extraction and quality assessment of included studies

The data from retrieved studies were independently extracted using standardised forms by two authors (AJO and CO-Z). Studies with insufficient data to estimate outcomes of interest were excluded. Collected data were validated by PD and JN. Any disagreement was resolved by LM. We extracted bibliometric information, such as author names, journal and year of publication. We also extracted the location of the study, study design, number of participants, outcomes reported, outcome measures overall and outcome measures in French-speaking participants.

Assessment of methodological quality of the included studies

We did not appraise the methodological quality and risk of bias of the studies as this is not required in a scoping review.21

Analyses and reporting

Our findings are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews guidelines, and we conducted a narrative synthesis of qualitative data to identify common themes and knowledge gaps.22–24

Results

Results of search

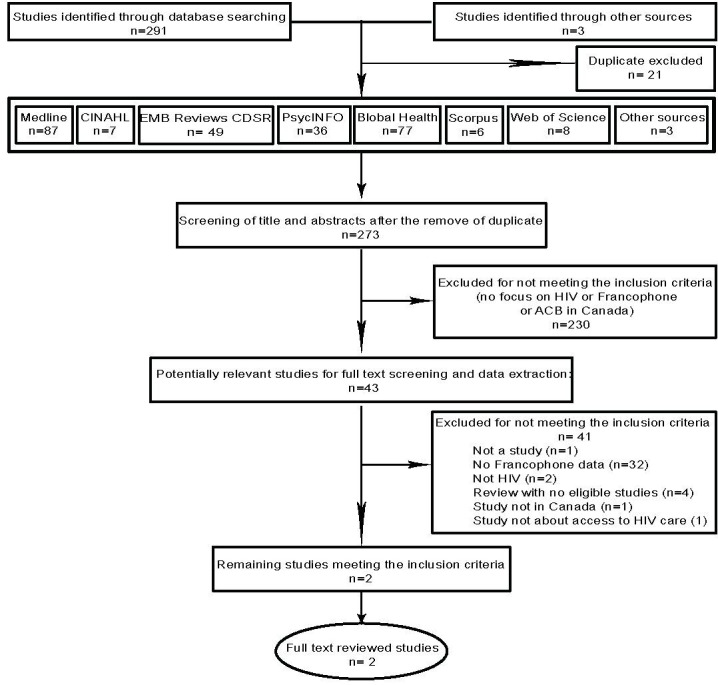

The literature search resulted in 291 studies through database searching (figure 1). Three studies were generated through other sources and grey literature (figure 1).1 25 26 A total of 273 studies were screened after duplicates were removed. Subsequently, 230 studies with no focus on HIV, Francophone or ACB in Canada were further excluded based on title and abstract screening. The full texts of 43 potentially relevant papers were retrieved for evaluation and data extraction. Forty-one studies were further excluded based on failure to meet the inclusion criteria (see online supplementary appendix 1): 1 paper was not a research article,27 32 studies had no Francophone data,17 28–57 2 studies were not on HIV,4 58 4 studies were reviews with no eligible studies,59–62 1 study was a study not conducted in Canada63 and 1 study was not about access to HIV care,64 leaving 2 studies that met our inclusion criteria (figure 1).9 10

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of studies selection. ACB, African Caribbean and Black; CDSR, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

bmjopen-2020-036885supp002.pdf (81.7KB, pdf)

Characteristics of included studies

Buissé et al (2006) conducted a qualitative study to explore the availability of Francophone specialised health and mental health services in the city of Winnipeg. In this study, 24 health service providers delivering services to Francophone immigrants and refugees in the city of Winnipeg were interviewed.10 The authors investigated outcomes, such as healthcare accessibility, services and continuity of care for new Francophone immigrants. They found that HIV and mental health services in the city of Winnipeg had only minimal Francophone capacity with Francophone staff being minimal to non-existent. This resulted in the use of unqualified interpreters or appointment rescheduling as some places had a 6-month waiting list. In some cases, HIV nurse specialists had to obtain materials from or refer Francophone clients to HIV websites in French. African Francophone health service providers described the situation as critical. Twenty-four health service providers from 19 organisations were interviewed for the study. All of these organisations did not meet eight of the nine criteria of Bachrach’s continuity of care principles for Francophone PLWH in general and African Francophone in particular. These principles include administrative environments that are capable of providing the aid their patients’ need, accessible care, multidisciplinary care, care customised to patients’ needs, adaptable use of different programmes and interventions, the extensive linkage between organisations caring for the patient, long-term caregivers who help patients access care, active patient involvement in organising services and culturally responsive programmes.2 Although these organisation had a full array of services, there was a lack of cultural awareness among healthcare providers as well as barriers in access to care and continuity of care for Francophone African newcomers living with HIV or mental illness in Winnipeg.10

Samson and Spector investigated the cultural sensitivity involved in HIV care delivery to Francophone minorities living with HIV in Ontario.9 This was a qualitative study conducted with a sample of 29 participants, including AIDS Service Organization (ASO) professionals and PLWH, between September and December 2009 in the cities of Ottawa and Toronto. The author used phenomenological analysis to categorise his findings into three themes.65

Social context of HIV care access in French

ASO professionals did not perceive offering bilingual services as a priority because their clients often had more severe and complex needs which required diverting time and resources to outreach and to addressing more immediate and urgent needs. Francophone PLWH (both Canadian-born and African-born) reported unmet expectations with respect to the delivery of services in French. Canadian Francophone PLWH perceived this as a rejection of their cultural identity and citizenship while African-born Francophone PLWH were shocked by the lack of service delivery in French in ASOs.

Language and cultural sensitivity and diversity

ASO professionals perceived linguistic differences as secondary. They recognised language as an aspect of the cultural diversity of their clientele but considered it as a neutral tool for service delivery which does not negate cultural differences. Because most Canadian PLWH speak English, and rarely demand service in their mother tongue, French language services are not a priority. They recognised that this might be a barrier for African-born clients but since there is no advocacy for French services, thus ASO professionals recognized that this might be a barrier for African-born clients, but since there is no advocacy for French services, they considered that not a priority. Canadian PLWH acknowledged initiating conversations at ASOs in English due to a fear of being rejected if they speak French. Both Canadian-born and African-born Francophone PLWH described positive experiences when they were able to obtain services in French. They considered that they were better understood and could express themselves better in these situations.

Emerging reality in Canada’s ACB Francophone communities

The study reported an increase in the clientele from French-speaking African countries due to a changing ethno-racial composition of the Franco-Ontarian community. This situation has created pressure for more French services in ASOs in Ontario. There is a greater awareness of the need to tend to linguistic differences as an aspect of cultural sensitivity. These unilingual French-speaking African-born PLWH described their linguistic isolation as a painful reminder of the rejection experienced in their countries of origin due to HIV/AIDS.

Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to identify existing gaps in healthcare access by and delivery to Francophone minorities living with HIV in Canada, and to uncover the reasons for healthcare disparities faced by Francophone ACBs living with HIV in Anglophone Canadian provinces and territories.

We identified two eligible studies from two provinces in Canada—Ontario and Manitoba. In Ontario, the most populated province in Canada, we found that issues exist regarding the availability of Francophone or bilingual healthcare and HIV/AIDS organisation workers. Several bilingual healthcare professionals report difficulties in providing quality healthcare to Francophone patients. They attributed this to scarcities in bilingual staff and problems communicating with patients who speak French when that was not the providers’ first language. Additionally, bilingual health providers also described often being overworked, since they would also take on interpretative roles on top of their regular work.9 11 12 These deficiencies in French services are also notable among Ontarian HIV/AIDS organisations, where lack of funding may have contributed to smaller numbers of bilingual staff.66 67 While language was acknowledged as an important cultural factor and communication tool, it was also frequently overlooked to better serve PLWH in Ontario by helping provide food, housing and mental services.9 The evidence of lack of French Language Healthcare Services (FLHS) in Ontario has been highlighted in previous research.68

In Manitoba, it is estimated that only 25% of Francophone have access to French healthcare services, with Franco-Manitobans and healthcare professionals alike reporting a far greater demand for Francophone services than what was available.3 69 Furthermore, new Francophone ACB immigrants to Manitoba were reported to have difficulties accessing specialised services such as counselling on HIV and mental health as well as HIV testing.10 Interestingly, although there are scarcities throughout Manitoba’s French healthcare, Anglophone Manitoban healthcare providers seemed to be under the assumption that Manitoba’s health resources were sufficient to meet demand.10 Moreover, a 2015 study reported that Francophone immigrants to Manitoba were more likely to wait for French healthcare services and interpreters. The waiting time for French services was far longer compared with Anglophone services.70

It is well established that language is critical to effective healthcare: it facilitates accurate transmission of knowledge between a provider and a patient and allows patients to effectively disclose their symptoms and medical history.10–12 Unfortunately, official language minorities frequently experience delays in healthcare due to difficulties finding interpreters and shortages in bilingual healthcare personnel and management staff, which can impact travel times, the accessibility and availability of specialised services and whether translated resources are present.3 9–12 Therefore, the well-documented deficiency of FLHS in Ontario and other provinces and territories where French is a minority language can and should be seen as a major barrier to the receipt of quality healthcare among Francophone ACB living with HIV.10 25 68

Bearing in mind the enormous importance of a common language in patient–provider interactions, it is evident that Francophone ACBs in a majority English-speaking provinces and territories are much more likely to experience lower quality healthcare services than their Anglophone counterparts. In both healthcare and HIV/AIDS organisations outside of Quebec, individuals in need of French language services are expected to advocate for resources.25 Yet, practitioners and organisation workers frequently note that their Francophone patients would communicate in English over French, if they could, even if it meant less information being communicated overall. Several explanations have been postulated for this phenomenon: some healthcare workers think it may be due to clients’ fears of receiving lesser or delayed care if practitioners realised they were Francophone; others believe it may have to do with patients’ fears of HIV stigmatisation.3 9 10 12 69 70 This latter point is especially relevant to ACB PLWH, since stigma, discrimination and race are all associated with poor access to care and retention in care.71–73 Considering that ACB people with HIV often face multiple forms of stigma, not only due to ethnicity or HIV status, language barriers can present a stigmatising and significant hurdle to health and well-being in this population.74

Research has also shown that cultural differences should be considered in addition to stigma, since ignoring these factors can have a negative impact on HIV prevention interventions.17 75–77 Lack of consideration for these issues has been shown to be detrimental to the health of African-born Francophone PLWH, who were not being able to access services in French as it reinforced their sense of isolation in a new and unfamiliar country.9 10 Moreover, ACB focus groups in Toronto suggested that to be successfully effective, HIV treatments and interventions in the ACB communities should be culturally appropriate and sensitive.54

Limited research into Francophone ACB populations in Canada makes it difficult to evaluate how French healthcare deficiencies impact their HIV care continuum. For instance, while Manitoba reported 116 new cases of HIV in 2005, of which approximately 21% were from ACB populations, it is unknown how many of these patients were Francophone.78 Moreover, although Buissé’s study described ‘minimal to non-existent’ numbers of Francophone HIV and tuberculosis (TB) counselling specialists, there were no records of how many clients were expected to require those services or how many had come in for HIV diagnosis and treatment. It could also be possible that given the paucity of Francophone HIV and TB specialists at the time, the actual rates of HIV diagnosis could indeed be higher.10

In Ontario, while 25.3% of 2017s 1184 new HIV diagnoses are estimated to come from ACB populations, data on race and ethnicity was only available for 43.1% of the population. Similar to Manitoba, no information on Francophone populations was available.79 Thus, the collection of data on Francophone on the provision of bilingual healthcare services is critical to developing effective HIV prevention programmes for Francophone ACB communities.

This study answers important questions related to access to care for Francophone ACB people living with or affected by HIV in Canada. Furthermore, this scoping review investigated the impact of intersectionality, the French language, race and HIV stigma on ACB access to HIV care. The global relevance of this study is limited, since this scoping review is focused only on Canada. Similarly, although Francophone healthcare deficits have been noted in several provinces other than Quebec, information on HIV care in Francophone ACB populations was limited to only two studies.3 4 12 69 80–82 The low number of included studies is due to the fact that although there are more studies on Francophone health and access to healthcare in general, not enough studies are focused on HIV in the Francophone and Francophone ACB communities. Thus, while the two studies outlined in this scoping review did describe significant barriers to HIV care for Francophone the small number of studies addressing HIV care deficiencies among Francophone ACBs who do not live in Quebec makes it difficult to estimate HIV care disparities in provinces and territories other than Ontario and Manitoba.

Conclusion

This research has shown that culturally sensitive health-related service provision should include considerations of language, especially in the context of an officially bilingual country, where clients have a legitimate claim to such services. Providing services in a client's first language value their identity and allow for better care of those individuals. The findings of this scoping review should inform changes in health policymaking, community organisations and HIV/AIDS centre, such as increasing training and recruitment of bilingual healthcare practitioners, especially specialists, and ASO staff. These bilingual providers would be instrumental in providing and improving access to healthcare for Francophone ACB immigrants and Canadians. The paucity of data on HIV care for Francophone ACB immigrants or Canadians demonstrates the need for more HIV research to be done within these linguistic minority communities. This research may be vital in advancing our knowledge on which aspects of Canadian healthcare systems impose the most significant barriers to HIV care, testing, counselling and treatment among ACB communities.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: The study was conceived by PD, LM, JN and LEN. All authors revised the research question and provided content to the design. Manuscript was written and edited by PD, AY, LM, JN, LEN, CM, CO-Z, AJO and DL. Principal investigator of the study is LEN. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by the Ontario HIV Treatment Network Applied HIV Research Chair in HIV Program Science with African, Caribbean and Black Communities #AHRC-1066; core services and support from the University of Rochester Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI078498); and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research through an Operating Grant in the HIV/AIDS Community-Based Research (CBR) Program.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the 'Methods and analysis' section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.Study co-ordinated by the fédération des communautés francophones et acadienne (FCFA) du Canada for the consultative committee for French-speaking minority communities Improving access to French language health services, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachrach LL. Continuity of care and approaches to case management for long-term mentally ill patients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993;44:465–8. 10.1176/ps.44.5.465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Moissac D, Bowen S. Impact of language barriers on access to healthcare for official language minority Francophones in Canada. Healthc Manage Forum 2017;30:207–12. 10.1177/0840470417706378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernier AM, et al. A survey on health care access in French for francophone immigrants in Winnipeg, Canada. Articles from the 13th World Congress on Public Health, 2013: 65–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bélanger M, Bouchard L, Gaboury I, et al. Perceived health status of francophones and anglophones in an officially bilingual Canadian Province. Can J Public Health 2011;102:122–6. 10.1007/BF03404160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simbiri KOA, Hausman A, Wadenya RO, et al. Access impediments to health care and social services between Anglophone and Francophone African immigrants living in Philadelphia with respect to HIV/AIDS. J Immigr Minor Health 2010;12:569–79. 10.1007/s10903-009-9229-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forgues Éric, Landry R, Boudreau J. Identifying francophones: an analysis of definitions based on census variables, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Djiadeu P, Nguemo J, Mukandoli C, et al. Barriers to HIV care among francophone African, Caribbean and black immigrant people living with HIV in Canada: a protocol for a scoping systematic review. BMJ Open 2019;9:e027440. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samson AA, Spector NMP. Francophones living with HIV/AIDS in Ontario: the unknown reality of an invisible cultural minority. AIDS Care 2012;24:658–64. 10.1080/09540121.2011.630350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buissé D. An analysis of crisis services accessibility of new francophone arrivals in the city of Winnipeg, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drolet M, Savard J, Benot J, et al. Health services for linguistic minorities in a bilingual setting: challenges for bilingual professionals. Qual Health Res 2014;24:295–305. 10.1177/1049732314523503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Timony PE, Gauthier AP, Serresse S, et al. Barriers to offering French language physician services in rural and Northern Ontario. Rural Remote Health 2016;16:3805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ontario Go. The French language services act, 1986 (FLSA), 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Census Census profile, 2016 census, 2016. Available: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

- 15.Bourgeois AC, Edmunds M, Awan A, et al. HIV in Canada-Surveillance report, 2016. Can Commun Dis Rep 2017;43:248–56. 10.14745/ccdr.v43i12a01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ojikutu B, Nnaji C, Sithole-Berk J, et al. Barriers to HIV testing in black immigrants to the U.S. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2014;25:1052–66. 10.1353/hpu.2014.0141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardezi F, Calzavara L, Husbands W, et al. Experiences of and responses to HIV among African and Caribbean communities in Toronto, Canada. AIDS Care 2008;20:718–25. 10.1080/09540120701693966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med 2005;37:360–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:141–6. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernardo WM. PRISMA statement and Prospero. Int Braz J Urol 2017;43:383–4. 10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2017.03.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Oliveira BGRB. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowen S. Language barriers in access to health care/barrières linguistiques dans l'accès aux soins de santé. Public Health Agency of Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowen S. The impact of language barriers on patient safety and quality of care. Société Santé en français, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anonymous HIV-positive man from DRC deemed a ‘person in need of protection’. HIV/AIDS Policy & Law Review 2008;13:30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration (ART-CC) Influence of geographical origin and ethnicity on mortality in patients on antiretroviral therapy in Canada, Europe, and the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:1800–9. 10.1093/cid/cit111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baidoobonso S, Bauer GR, Speechley KN, et al. Social and proximate determinants of the frequency of condom use among African, Caribbean, and other black people in a Canadian City: results from the BLACCH study. J Immigr Minor Health 2016;18:67–85. 10.1007/s10903-014-9984-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baidoobonso S, Bauer GR, Speechley KN, et al. HIV risk perception and distribution of HIV risk among African, Caribbean and other black people in a Canadian city: mixed methods results from the BLACCH study. BMC Public Health 2013;13:184. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blot S, Bauer G, Fraser M, et al. AIDS service organization access among African, Caribbean and other black residents of an average Canadian city. J Immigr Minor Health 2017;19:851–60. 10.1007/s10903-016-0359-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Browne OA. Assessing healthcare providers’ responses to African and Caribbean families living with HIV. Dissertation abstracts international section A: Humanities and social sciences. 69, 2009: 2753. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burton K, Ayangeakaa S, Kerr J, et al. Examining sexual concurrency and number of partners among African, Caribbean, and black women using the social ecological model: results from the ACBY study. Can J Hum Sex 2019;28:46–56. 10.3138/cjhs.2018-0033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Csete J. ‘Vectors, vessels and victims’: HIV/AIDS and women’s human rights in Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.dela Cruz AMM. A narrative inquiry into the experiences of sub-Saharan African immigrants living with HIV in Alberta, Canada. dissertation abstracts international: section B: the sciences and engineering 2017;77(9-B(E. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kapiriri L, Tharao W, Muchenje M, et al. How acceptable is it for HIV positive African, Caribbean and black women to provide breast milk/fluid samples for research purposes? BMC Res Notes 2017;10:7. 10.1186/s13104-016-2326-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kapiriri L, Tharao WE, Muchenje M, et al. The experiences of making infant feeding choices by African, Caribbean and black HIV-positive mothers in Ontario, Canada. World Health Popul 2014;15:14–22. 10.12927/whp.2014.23860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khan S, Ion A, Alyass A, et al. Loneliness and perceived social support in pregnancy and early postpartum of mothers living with HIV in Ontario, Canada. AIDS Care 2019;31:318–25. 10.1080/09540121.2018.1515469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kippax SC, Aggleton P, Moatti J-P, et al. Living with HIV: recent research from France and the French Caribbean (Vespa study), Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom. AIDS 2007;21:S1–3. 10.1097/01.aids.0000255078.01234.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krusi A, et al. Marginalized women living with HIV at increased risk of viral load suppression failure: implications for prosecutorial guidelines regarding criminalization of HIV non-disclosure in Canada and globally. J Int AIDS Soc 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li AT-W, Fung KP-L, Maticka-Tyndale E, et al. Effects of HIV stigma reduction interventions in diasporic communities: insights from the CHAMP study. AIDS Care 2018;30:739–45. 10.1080/09540121.2017.1391982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Logie C, et al. Developing and pilot testing transcending love, a multi-methods arts based workshop with African, Caribbean and black transgender women. J Int Aids Soc 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Logie CH, Kaida A, de Pokomandy A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of forced sex as a self-reported mode of HIV acquisition among a cohort of women living with HIV in Canada. J Interpers Violence 2017:886260517718832. 10.1177/0886260517718832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Logie CH, Kennedy VL, Tharao W, et al. Engagement in and continuity of HIV care among African and Caribbean black women living with HIV in Ontario, Canada. Int J Std Aids 2017;28:969–74. 10.1177/0956462416683626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Logie CH, Lacombe-Duncan A, Lee-Foon N, et al. ‘It’s for US-newcomers, LGBTQ persons and HIV-positive persons. you feel free to be’: social support groups as an HIV prevention strategy with LGBTQ African, Caribbean and black newcomers and refugees in Toronto, Canada. BMC Int Health Human Right 2015;26:24B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Logie CH, Okumu M, Ryan S, et al. Adapting and pilot testing the healthy love HIV and sexually transmitted infection prevention intervention with African, Caribbean and black women in community-based settings in Toronto, Canada. Int J Std Aids 2018;29:751–9. 10.1177/0956462418754971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loutfy M, de Pokomandy A, Kennedy VL, et al. Cohort profile: the Canadian HIV women’s sexual and reproductive health cohort study (CHIWOS). PLoS One 2017;12:e0184708. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Masindi K-I, Jembere N, Kendall CE, et al. Co-morbid non-communicable diseases and associated health service use in African and Caribbean immigrants with HIV. J Immigr Minor Health 2018;20:536–45. 10.1007/s10903-017-0681-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakyonyi MM. HIV/AIDS education participation by the African community. Can J Public Health 1993;84 Suppl 1:S19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nelson LE, et al. A recipe for increasing racial and gender disparities in HIV infection: a critical analysis of the Canadian guideline on pre-exposure prophylaxis and non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis’ responsiveness to the HIV epidemics among women and Black communities. Canad J Human Sex 2019;28:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tulloch HE, Balfour L, Kowal J, et al. HIV knowledge among Canadian-born and sub-Saharan African-born patients living with HIV. J Immigr Minor Health 2012;14:132–9. 10.1007/s10903-011-9480-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Umamaheswaran-Mahara M, Hunter AJ. Health status of a paediatric urban refugee and immigrant population in Canada. Paediatr Child Health 2010;15:48A 10.1093/pch/15.suppl_A.48Aa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Webster K, Carter A, Proulx-Boucher K, et al. Strategies for recruiting women living with human immunodeficiency virus in community-based research: lessons from Canada. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2018;12:21–34. 10.1353/cpr.2018.0003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams CC, Newman PA, Sakamoto I, et al. HIV prevention risks for black women in Canada. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:12–20. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Worthington C, Este D, Strain K-L, et al. African immigrant views of HIV service needs: gendered perspectives. AIDS Care 2013;25:103–8. 10.1080/09540121.2012.687807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Worthington CA, Calzavara LM, White SJ, et al. Individual and jurisdictional factors associated with voluntary HIV testing in Canada: results of a national survey, 2011. Can J Public Health 2014;106:e4–9. 10.17269/CJPH.106.4625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhabokritsky A, Nelson LE, Tharao W, et al. Barriers to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among African, Caribbean and black men in Toronto, Canada. PLoS One 2019;14:e0213740. 10.1371/journal.pone.0213740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pottie K, Ng E, Spitzer D, et al. Language proficiency, gender and self-reported health: an analysis of the first two waves of the longitudinal survey of immigrants to Canada. Can J Public Health 2008;99:505–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aidala AA, Wilson MG, Shubert V, et al. Housing status, medical care, and health outcomes among people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2016;106:e1–23. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ha S, Paquette D, Tarasuk J, et al. A systematic review of HIV testing among Canadian populations. Can J Public Health 2014;105:e53–62. 10.17269/cjph.105.4128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jbilou J, et al. Men-centered approaches for primary and secondary prevention of HIV/AIDS: a scoping review of effective interventions. J AIDS Clin Res 2013;4:257. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mbuagbaw L, Mertz D, Lawson DO, et al. Strategies to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy and retention in care for people living with HIV in high-income countries: a protocol for an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022982. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith ML, Read S, Bitnun A. Neurocognitive development in young HIV-exposed uninfected children exposed pre-or perinatally to antiretroviral medications. Canad J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2014;25:65A. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaida A, Carter A, Nicholson V, et al. Hiring, training, and supporting peer research associates: Operationalizing community-based research principles within epidemiological studies by, with, and for women living with HIV. Harm Reduct J 2019;16:47. 10.1186/s12954-019-0309-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Englander M. The phenomenological method in qualitative psychology and psychiatry. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2016;11:30682. 10.3402/qhw.v11.30682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mail TGA. Ontario to lay off more than 400 people at health agencies as government continues cutting jobs, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Canada GN. Ontario government to slash funding to Toronto public health officials say, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Farmanova E, Bonneville L, Bouchard L. Active offer of health services in French in Ontario: analysis of reorganization and management strategies of health care organizations. Int J Health Plann Manage 2018;33:e194–209. 10.1002/hpm.2446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.de Moissac D, Bowen S. Impact of language barriers on quality of care and patient safety for official language minority Francophones in Canada. J Patient Exp 2019;6:24–32. 10.1177/2374373518769008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Moissac D, Giasson F, Roch-Gagné M. Accès aux services sociaux et de santé en français: l’expérience des Franco-Manitobains. Minorités linguistiques et société/Linguistic Minorities and Society 2015;6:42–65. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Logie C, James L, Tharao W, et al. Associations between HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, gender discrimination, and depression among HIV-positive African, Caribbean, and black women in Ontario, Canada. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:114–22. 10.1089/apc.2012.0296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Loutfy M, Tharao W, Logie C, et al. Systematic review of stigma reducing interventions for African/Black diasporic women. J Int AIDS Soc 2015;18:19835. 10.7448/IAS.18.1.19835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Dovidio JF, et al. Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: moving toward resilience. Am Psychol 2013;68:225–36. 10.1037/a0032705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Logie CH, James L, Tharao W, et al. HIV, gender, race, sexual orientation, and sex work: a qualitative study of intersectional stigma experienced by HIV-positive women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001124. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aidala AA, Lee G, Howard JM, et al. HIV-positive men sexually active with women: sexual behaviors and sexual risks. J Urban Health 2006;83:637–55. 10.1007/s11524-006-9074-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aidala AA, Lee G, Garbers S, et al. Sexual behaviors and sexual risk in a prospective cohort of HIV-positive men and women in New York City, 1994-2002: implications for prevention. AIDS Educ Prev 2006;18:12–32. 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Newman PA, Williams CC, Massaquoi N, et al. HIV prevention for black women: structural barriers and opportunities. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2008;19:829–41. 10.1353/hpu.0.0043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Manitoba Manitoba health statistical update on HIV/AIDS 1985 to 2005, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Haddad N, Li JS, Totten S, et al. HIV in Canada-surveillance report, 2017. Can Commun Dis Rep 2018;44:324–32. 10.14745/ccdr.v44i12a03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Farmanova E, Bonneville L, Bouchard L. Organizational health literacy: review of theories, frameworks, guides, and implementation issues. Inquiry 2018;55:46958018757848. 10.1177/0046958018757848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ngwakongnwi E, Hemmelgarn BR, Musto R, et al. Experiences of French speaking immigrants and non-immigrants accessing health care services in a large Canadian city. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2012;9:3755–68. 10.3390/ijerph9103755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gauthier AP, Timony PE, Serresse S, et al. Strategies for improved French-language health services: perspectives of family physicians in northeastern Ontario. Can Fam Physician 2015;61:e382–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-036885supp001.pdf (41.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-036885supp002.pdf (81.7KB, pdf)