Abstract

Purpose

Utilization of hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and supportive therapy drugs in hospitals in New York during the early weeks of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic was analyzed.

Summary

Drug utilization trends for 7 medications used to treat patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 at 47 New York hospitals were identified. The data demonstrated sharp increases in aggregate utilization of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine and the number of patients receiving either drug beginning on March 15, with a notable 20% median increase per day through March 31. The net quantity of drug charge units per day for midazolam, propofol, ketamine, cisatracurium, and fentanyl also increased during the study period. Following peak utilization, use of all study drugs decreased at different times throughout April 2020. The data were used to provide information to various stakeholders in the drug supply chain during the initial surge of the pandemic.

Conclusion

This analysis describes the increased use, beginning in mid-March 2020, of hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, midazolam, propofol, ketamine, cisatracurium, and fentanyl in 47 hospitals in New York State. The increased utilization of supportive therapy drugs was consistent with the surge in patients with presumed or confirmed COVID-19 during the study period. These data and observations can help clinicians, health-system leaders, manufacturers, wholesalers, and policymakers understand the impact of current and future pandemics on the drug supply chain.

Keywords: coronavirus, COVID-19, SARS-COV-2, hydroxychloroquine, pandemic, real-world data

KEY POINTS

Utilization of select drugs used for treatment or supportive care of patients with COVID-19 increased sharply at study hospitals between March 1 and May 16, 2020, consistent with the surge in hospitalized patients in New York State.

Manufacturers and wholesalers can use this analysis to enhance production forecasting and implement dynamic allocation strategies to ensure that hospitals or regions in need will receive appropriate allocation of medications subject to shortages.

Access to timely analytics and real-world data will help health systems to manage drug utilization and plan for alternatives.

In December 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was first reported in Wuhan, China, and the disease began to spread rapidly throughout China over the next 2 months.1 On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak a public health emergency of international concern,2 and by February 2 new cases were confirmed in India, the Philippines, Russia, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, Germany, Japan, Singapore, the United States, the United Arab Emirates, and Vietnam.3 Within the next month all 50 states in the United States had reported cases of COVID-19,4 and on March 11 the COVID-19 outbreak was characterized as a pandemic by WHO.5

In the United States, the first case of COVID-19 was announced on January 21, 2020, in Washington State.6 On the opposite coast, New York State quickly emerged as an epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic, with 138,773 cases as of April 77 relative to the entire US count of 395,011 cases.8 Moreover, on the same date New York City (NYC) had a COVID-19 case fatality ratio of 5.3%, compared with a ratio of 3.2% in the rest of the United States.4

The virus that causes COVID-19, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), can cause mild to severe respiratory disease and is primarily transmitted from person to person via respiratory droplets.9 Approximately 1 in every 5 people who develop COVID-19 become seriously ill, have difficulty breathing,10 and can experience major complications, including acute respiratory distress syndrome.11 Additional sequelae observed in critically ill patients with COVID-19 include pneumonia, sepsis and septic shock, cardiomyopathy and arrhythmia, acute kidney injury, and complications resulting from prolonged hospitalization.12 In these patients, mechanical ventilation is often required, necessitating supportive medications such as neuromuscular blockers, sedatives, and analgesics.

As of the time of the study described here, there were no known effective treatments, preventative agents, or vaccines for COVID-19. In addition to supportive care, several medications, including some not commercially available in the United States, and investigational treatments have been proposed for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2–positive patients, including hydroxychloroquine sulfate, chloroquine phosphate, remdesivir, baloxavir, favipiravir, HIV protease inhibitors, neuraminidase inhibitors, and umifenovir.13

The rapid surge of hospitalized patients in New York State required hospitals and public health officials to evaluate patient care resources, including medication supply, and develop triage plans for available supplies on hand. In April and May 2020, other hospitals across the United States experienced increased number of hospital admissions as research on evidence for COVID-19–related treatments continued to emerge. The data and observations outlined in this article can help clinicians, health-system leaders, manufacturers, and wholesalers understand the impact of current and future pandemics on the drug supply chain.

Methods

The purpose of the study was to describe medication utilization for select medications in a population of patients with presumed COVID-19 in New York State in March, April, and May 2020.

A descriptive design was employed in an analysis of real-world data from 47 hospitals in New York State using the Comparative Rapid Cycle Analytics platform (Agilum Healthcare Intelligence, Deerfield Beach, FL) to identify current utilization trends for selected medications. Medications selected were those known to be used to treat or provide supportive care for patients with COVID-19 and, at the time of selection, subject to intermittent availability from wholesalers, with subsequent drug shortages reported. Agilum’s platform contains real-world data on 130 million patients from hospitals and clinics across the country. Data are received daily in near real time, enabling timely reporting of information and utilization trends. From the compiled Agilum data for the medications selected, inpatient and outpatient drug charge-unit data from hospital pharmacy and financial systems were extracted for analysis. With supply chain sources fluctuating, purchases were not included in the analysis (these data were excluded in order to avoid any data gaps). The numbers of inpatients and outpatients receiving the selected medications were tracked each day and reported to evaluate utilization demand per patient per day to document downstream impacts on the drug supply chain.

Inpatient and outpatient utilization data for 7 medications from 47 (21%) of 229 New York hospitals, collectively representing 13,196 (29%) of the 46,301 staffed hospital beds in New York State for the period March 1 through May 16, 2020, were analyzed. Temporary hospitals set up during the pandemic were excluded from the hospital count. Of the 47 hospitals included, 46 are short-term acute care hospitals, representing 30% of the total of 155 acute care hospitals in New York State. The one remaining study hospital is a critical access hospital (Table 1). The study hospitals ranged in size from small (less than 100 beds) to large (over 500 beds). A majority of the study hospitals (53%) were 100- to 499-bed hospitals (Table 2). Nineteen of the 47 study hospitals (40%) are located in NYC, 3 hospitals are located in NYC suburbs, and 25 are located across the state outside of NYC and its suburbs. For the purposes of the study, suburbs were defined as areas within 35 miles of NYC.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Hospitals Relative to All New York Hospitals

| Characteristic | All New York Hospitals, n | Study Hospitals, No. (% of n) |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital type | ||

| Short-term acute care | 155 | 46 (30) |

| Critical access | 18 | 1 (0.5) |

| Othera | 56 | 0 |

| Total | 229 | 47 (21) |

| Licensed beds | ||

| Short-term acute care hospitals | 38,946 | 13,171 (34) |

| Critical access hospitals | 415 | 25 (6) |

| Other hospitalsa | 6,940 | 0 |

| Total | 46,301 | 13,196 (29) |

aPsychiatric hospitals, Veterans Affairs hospitals, children’s hospitals, long-term acute care hospitals, Department of Defense hospitals, religious nonmedical healthcare institutions, and rehabilitation hospitals.

Table 2.

Size of Study Hospitals by Number of Licensed Beds

| Size Category | No. (%) Hospitals | No. (%) Beds per Category |

|---|---|---|

| >1,000 beds | 2 (4) | 2,525 (19) |

| 500–999 beds | 8 (17) | 4,737 (36) |

| 300–499 beds | 9 (19) | 2,486 (19) |

| 100–299 beds | 16 (34) | 2,775 (21) |

| <100 beds | 12 (26) | 673 (5) |

| Total | 47 (100) | 13,196 (100) |

The study drugs included hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine tablets and the injectable forms of midazolam, propofol, ketamine, cisatracurium, and fentanyl. These medications were selected for the analysis because of high utilization in patients with COVID-19 at the time of the study and growing critical shortages of the drugs.

Daily patient counts and the net charge-unit quantity per day for all study drugs were calculated. Credits or medications returned to stock were accounted for in the net charge-unit quantity. No exclusions were made for the use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine, or any of the supportive medications, for the treatment of diseases other than COVID-19 in our analysis of drug utilization. For the purpose of the drug utilization review and descriptive analysis, charge units were considered net doses administered to patients. The information and narrative presented were current as of May 16, 2020.

The drug utilization review was deemed to be exempt from institutional review board review.

Results

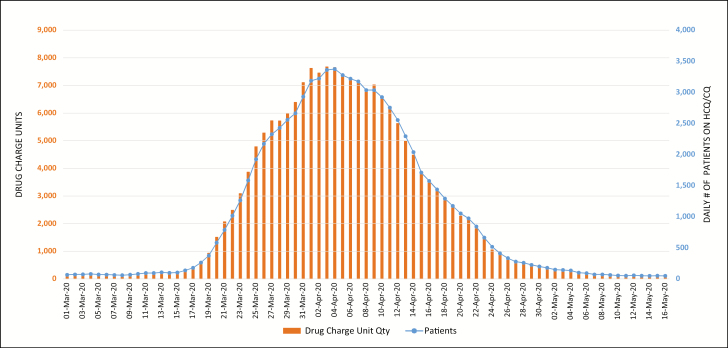

All of the 47 New York State hospitals included in the utilization review had net charge-unit data for the 5 supportive therapy drugs, whereas only 41 of the hospitals had net charge-unit data for hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine. Figure 1 represents the daily count of patients who were receiving hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine and the corresponding net charge-unit quantities from March 1 through May 16.

Figure 1.

Trends in daily count of patients who received hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) or chloroquine (CQ) at the study hospitals and corresponding net charge-unit quantities from March 1 through May 16, 2020.

Trends in drug utilization and daily numbers of patients treated with hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine from March 1 through March 31 were identified. The data demonstrated sharp increases in utilization of and number of patients receiving hydroxychloroquine beginning on March 15, with a notable 20% median increase per day through March 31. On April 3, utilization reached a peak, with 7,674 drug charge units, representing a 21.2-fold increase from March 17. The change in utilization dropped to an average of 2% per day in the beginning of April and then showed a trend downward.

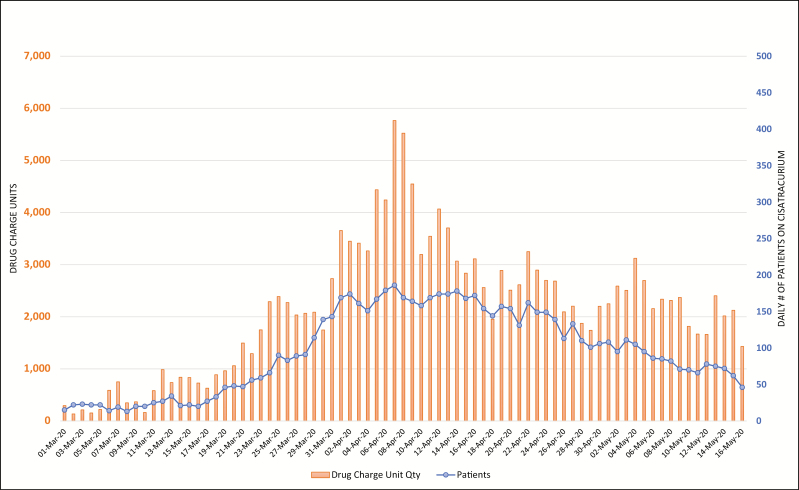

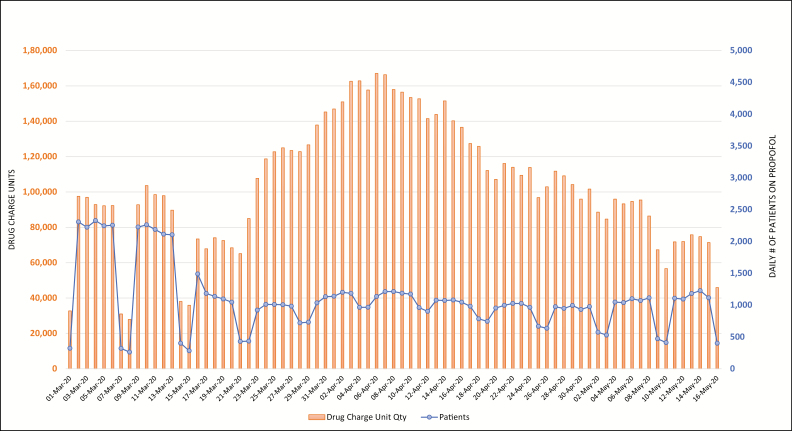

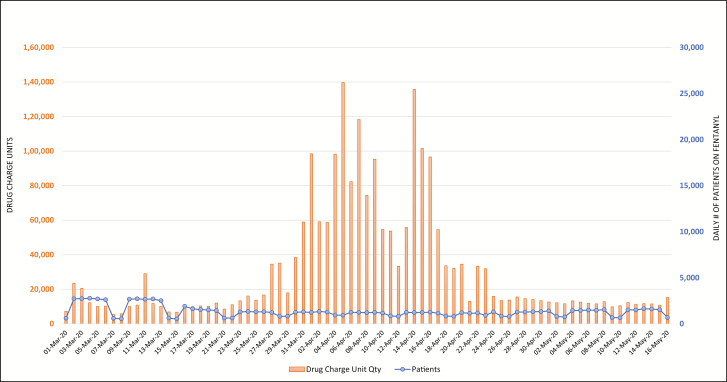

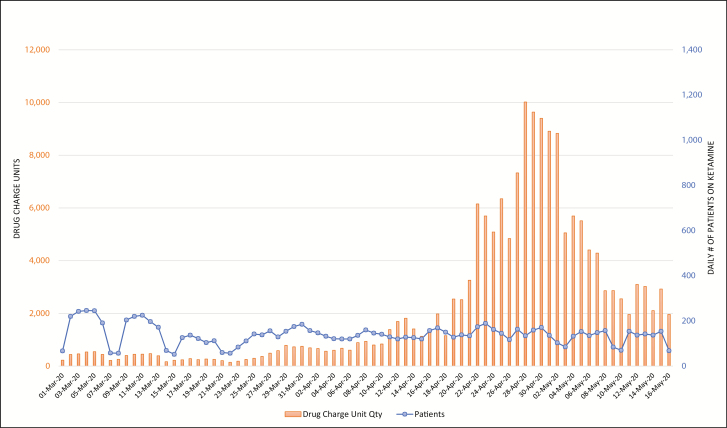

Figures 2 through 6 display daily counts of patients who received the 5 supportive medications and the charged units (defined as net quantity of drug unit charges per day) of midazolam, propofol, ketamine, cisatracurium, and fentanyl from March 1 through May 16. The data show an upward shift in utilization trends for all 5 drugs. The utilization of midazolam, propofol, fentanyl, ketamine, and cisatracurium began trending up in mid- to late March, with propofol and cisatracurium use peaking between April 3 and April 9. Midazolam and fentanyl utilization had more than one peak, with midazolam peaking at the end of March and then again in mid- and late April and fentanyl peaking in early and mid-April. Ketamine utilization increased gradually in early April and increased markedly in mid- to late April and again on April 28. Utilization of all study medications decreased into May. Ketamine and fentanyl had the largest increases from baseline. The numbers of patients receiving fentanyl, ketamine, propofol, and midazolam decreased during the study period; however, the overall utilization of these drugs increased. Both the number of patients receiving cisatracurium and the overall utilization of cisatracurium increased during the study period.

Figure 2.

Trends in daily count of patients who received midazolam at the study hospitals and corresponding net charge-unit quantities from March 1 through May 16, 2020.

Figure 6.

Trends in daily count of patients who received cisatracurium at the study hospitals and corresponding net charge-unit quantities from March 1 through May 16, 2020.

Discussion

The data from our descriptive study of medication utilization in patients seen in hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York State demonstrated a sharp increases in use of the 6 out of 7 study drugs in mid-March 2020, which was consistent with the increase in numbers of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Medication use increased from approximately March 17 to April 28 and then began trending down.

The 21.2-fold increase in aggregate use of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine corresponded with an 18.9-fold increase in the number of patients receiving either drug during the same time period, suggesting that patients were being treated with these drugs. Although data on hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine use were combined for analysis, the mean percentage of hydroxychloroquine use was 99.5%, compared to only 0.5% for chloroquine, likely due to hydroxychloroquine’s more favorable toxicity profile.

The supportive therapy drugs included in the study, except for cisatracurium, are often used in surgeries and other procedures. At the beginning of the study period, the utilization patterns reflected higher numbers of patients receiving these drugs in lower doses, likely for surgeries or other procedures. As COVID-19 cases surged, fewer patients received supportive therapy drugs but utilization increased, reflecting higher, around-the-clock dosing. On the contrary, both the number of patients receiving cisatracurium and its overall utilization increased during the study period, suggesting that the drug was being used outside of surgeries and procedures, likely for neuromuscular blockade in critically ill patients.

Data from early March demonstrated baseline use of these supportive medications. The cyclical decrease in drug charge units of some medications during the weekends likely indicated use in elective surgeries. Throughout the month, the cyclical decreases diminished with the cancellation of elective surgeries by executive order of New York’s governor.14 As COVID-19 admissions may have leveled off or decreased in New York during the study time period, anecdotal reports from the study hospitals indicated that patients remained on ventilators, which may be a reflection of the continued high volume of use of some of the supportive therapy medications. Overall, our analysis showed that the patterned utilization trends evolved, causing the supply chain of the drugs to be impacted.

The unprecedented surge in use of these drugs strained the pharmaceutical supply chain. Pharmacists in the NYC metropolitan area described using small vial sizes to prepare large doses for continuous infusions. Drug shortages caused by COVID-19 preparedness and response in other regions of the country made the acquisition of more-desirable large vials of drugs difficult. Hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, midazolam, propofol, ketamine, cisatracurium, and fentanyl were all added to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Drug Shortages database due to increased demand; except for fentanyl, these medications have initial database posting dates from February 16 through April 10. As of May 16, all study medications were still listed in both the FDA and ASHP drug shortages databases, with the exception of chloroquine (the shortage had been resolved).15,16 A comprehensive, coordinated response by drug manufacturers, wholesalers, and federal regulators is required to prevent shortages like these in the future.

Emergency resource assessment and preparation are integral to health-system leadership and extend beyond pandemic preparedness, applying to a host of unforeseen events such as natural disasters and supply chain disruptions. On March 28, FDA issued an Emergency Use Authorization allowing hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate donated to the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) to be distributed and used for certain hospitalized patients with COVID-19.17 The SNS contains antibiotics, chemical antidotes, vaccines, antitoxins, and life-support medications and broad-range pharmaceuticals that can be sent to areas with a large-scale public health incident.18

Though it is not possible to predict the next drug treatment with potential benefit during the current or next pandemic, the data presented here show how rapidly and extensive the impact on hospitals and drug supplies could be. Hospital drug utilization data is an important tool wholesalers and manufacturers can use to anticipate and minimize supply chain interruptions. Manufacturers can use this data analysis to enhance production forecasting. Wholesalers can use this data analysis to implement dynamic allocation strategies to ensure that hospitals or regions in need will receive appropriate allocation of medications subject to shortages. Additionally, access to timely analytics will allow health systems to better control utilization and plan for alternatives. Emerging evidence is shifting utilization away from medications lacking efficacy to other agents, as possibly seen with the 2 antivirals included in our analysis (hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine). The results of the study are intended to help clinicians, health-system leaders, and manufacturers understand the impact of current and future pandemics on the drug supply chain and the value of real-world data in monitoring the evolving utilization trends.

The study had several limitations. Identification of daily trends was based on descriptive data that may not represent utilization trends in other cities or regions. The data include all uses of the reported drugs in all patients, both patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 and patients treated for diagnoses unrelated to COVID-19. The study did not include other therapies that may have been used to treat patients with COVID-19. COVID-19 treatment protocols may have varied among study hospitals, making it difficult to know if all patients with COVID-19 were treated with hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine during the entire study period. Further, trends in utilization may have been affected by drug availability and therefore do not necessarily account for therapeutic substitutions and attempts to conserve drugs. Data were collected over an abbreviated time frame during a peak in COVID-19 cases in New York State.

Additional monitoring of daily utilization trends and modeling are continually being analyzed. Longer-term data collection and analyses are needed to continue to advance and assist states in their efforts to prepare for similar surges. Further, as only a small subset of medications used to treat or support patients during the COVID-19 pandemic were analyzed in our study, the study results do not necessarily account for utilization of other critical and lifesaving medications.

Conclusion

Few drug utilization studies focusing on COVID-19 have been conducted. Our drug utilization review was, to our knowledge, the first to evaluate utilization trends for certain medications being used for the treatment of COVID-19 within multihospital health systems in New York State during a peak in the pandemic. The study’s descriptive analysis, conducted using real-world data from 21% of hospitals in New York State, demonstrated sharp increases in the use of hydroxychloroquine, midazolam, propofol, ketamine, cisatracurium, and fentanyl starting in mid-March. The increases in drug utilization were consistent with the surge in numbers of patients with COVID-19. Following peak utilization there was a decrease in utilization throughout April for all study drugs. The data and observations can support clinicians, health-system leaders, public health officials, manufacturers, wholesalers, and state and federal policymakers in data analysis to enhance medication production and forecasting of demand and supply for current or future pandemics.

Figure 3.

Trends in daily count of patients who received propofol at the study hospitals and corresponding net charge-unit quantities from March 1 through May 16, 2020.

Figure 4.

Trends in daily count of patients who received fentanyl at the study hospitals and corresponding net charge-unit quantities from March 1 through May 16, 2020.

Figure 5.

Trends in daily count of patients who received ketamine at the study hospitals and corresponding net charge-unit quantities from March 1 through May 16, 2020.

Disclosures

Dr. DeAngelo is employed by Agilum Healthcare Intelligence, Inc, whose data analytics platform was used in the drug utilization analysis. The other authors have declared no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov). Accessed April 13, 2020.

- 3. Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Coronavirus resource center https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed April 13, 2020.

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Geographic differences in COVID-19 cases, deaths, and incidence — United States, February 12–April 7, 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6915e4.htm. Accessed April 18, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Situation summary https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/summary.html#covid19-pandemic. Accessed April 13, 2020.

- 6. Washington State Department of Health. 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19) https://www.doh.wa.gov/emergencies/coronavirus. Accessed April 19, 2020.

- 7. New York State Department of Health. New York State Department of Health COVID-19 tracker https://covid19tracker.health.ny.gov/views/NYS-COVID19-Tracker/NYSDOHCOVID-19Tracker-Map?%3Aembed=yes&%3Atoolbar=no&%3Atabs=n. Accessed April 13, 2020.

- 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Number of COVID-19 cases in the U.S., by date reported https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/previouscases.html (accessed 2020 May 19). Accessed April 13, 2020.

- 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) frequently asked questions https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/faq.html#How-COVID-19-Spreads. Accessed April 18, 2020.

- 10. World Health Organization. Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19) https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses. Accessed April 19, 2020.

- 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 clinical care guidance May 2019 https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html. Accessed May 19, 2020.

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim clinical guidance for management of patients with confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html. Accessed April 22, 2020.

- 13. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP assessment of evidence for COVID-19-related treatments https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/pharmacy-practice/resource-centers/Coronavirus/docs/ASHP-COVID-19-Evidence-Table.ashx. Accessed April 14, 2020.

- 14. New York State. Executive order No 202.10: continuing temporary suspension and modification of laws relating to the disaster emergency https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/no-20210-continuing-temporary-suspension-and-modification-laws-relating-disaster-emergency. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- 15. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Shortages https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/drugshortages/default.cfm. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- 16. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Drug Shortages https://www.ashp.org/Drug-Shortages. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- 17. Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization: therapeutics https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/mcm-legal-regulatory-and-policy-framework/emergency-use-authorization#covidtherapeutics. Accessed May 22, 2020.

- 18. US Department of Health and Human Services. Public health emergency https://www.phe.gov/about/sns/Pages/products.aspx. Published April 16, 2020. Accessed April 19, 2020.