Abstract

Background

The impact of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has many facets. This ecological study analysed age-standardized incidence rates by economic level in Barcelona.

Methods

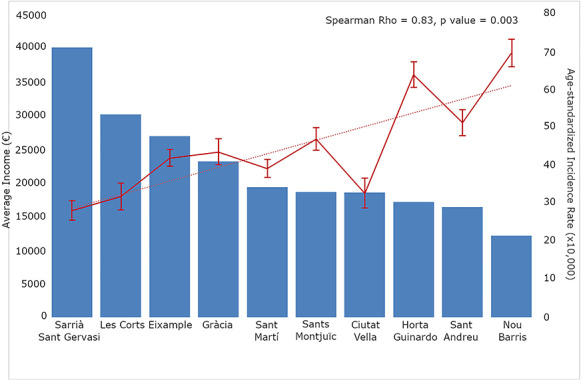

We evaluated confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Barcelona (Spain) between 26 February 2020 and 19 April 2020. Districts were classified according to most recent (2017) mean income data. The reference for estimating age-standardized cumulative incidence rates was the 2018 European population. The association between incidence rate and mean income by district was estimated with the Spearman rho.

Results

The lower the mean income, the higher the COVID-19 incidence (Spearman rho = 0.83; P value = 0.003). Districts with the lowest mean income had the highest incidence of COVID-19 per 10 000 inhabitants; in contrast, those with the highest income had the lowest incidence. Specifically, the district with the lowest income had 2.5 times greater incidence of the disease, compared with the highest-income district [70 (95% confidence interval 66–73) versus 28 (25–31), respectively].

Conclusions

The incidence of COVID-19 showed an inverse socioeconomic gradient by mean income in the 10 districts of the city of Barcelona. Beyond healthcare for people with the disease, attention must focus on a health strategy for the whole population, particularly in the most deprived areas.

Keywords: coronavirus infections, COVID-19, epidemiology, healthcare disparities, socioeconomic factors

Introduction

The outbreak of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in China’s Hubei province quickly spread nearly all over the world, with staggering medical, social and economic consequences.1 Worldwide, the pandemic accounts for more than 10 million confirmed cases and 500 000 deaths. While the USA, Brazil, Russia or UK presented the highest absolute numbers, Belgium, UK and Spain had the highest death rates.2,3 Thus, the figures made available in Spain by the Ministry of Health on 30 June 2020 showed 249 271 confirmed cases (5986 cases x 100 000 inhabitants), of which 125 183 were hospitalized and 11 664 required intensive care. Finally, this disease accounted for 28 355 deaths, with a case-fatality rate of 11.4%.4

Several authors have posed a possible socioeconomic gradient in the COVID-19 outbreak5–7 and differences in knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19 by socioeconomic status.8,9 Health inequalities have been pointed out in the context of the pandemic, not only in low- and middle-income countries, but also in high-income countries among deprived populations (e.g. having low income or lacking health insurance).10–13 In addition, the COVID-19 crisis has revealed the fragility of ageing societies to cope with infectious diseases in modern times. Indeed, individuals older than 70 years accounted for more than 85% of registered deaths in Italy.14 However, few studies in high-income countries have analysed the age-adjusted impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in deprived and non-deprived areas, as measured by average income.

The objective of this study was to analyse the differences in COVID-19 age-standardized incidence rate by mean income of the 10 districts of the city of Barcelona.

Methods

For this ecological study, all cases of COVID-19 confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for which data were available to ascertain the patient’s primary care centre in the city of Barcelona were extracted from the official COVID-19 registry of the Catalan Government’s Department of Health. The primary care centres were then classified according to their corresponding district in order to obtain the total count of cases by district from 26 February 2020, when the first case reported in the city,15 until 19 April 2020. The most recent (2017) information on the average income by district was extracted from official data provided by the Barcelona City Council. The estimate used was the Family Available Income per capita, which considers the income available for consumption and accumulated savings per person.16 This analysis followed the regulations in European Union law on data protection and privacy for all individuals within the European Union (GDPR/2018), the Declaration of Helsinki on ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects.

The crude incidence rates were estimated per 10 000 individuals, assuming the age distribution (<25 years, ≥25 and < 40 years, ≥40 and < 65 years and ≥65 years) of COVID-19 cases in Barcelona was similar to that reported for Spain.17 To standardize the incidence rates by age, we used the direct method with the 2018 European population as the reference.18 Age-adjusted cumulative incidence was calculated with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI). To ascertain the statistical association between the age-adjusted incidence rate and the mean income by district, Spearman rho was adjusted. The analysis was performed with R statistical software (version 3.6.3) and Epidat software (version 3.1).

Results

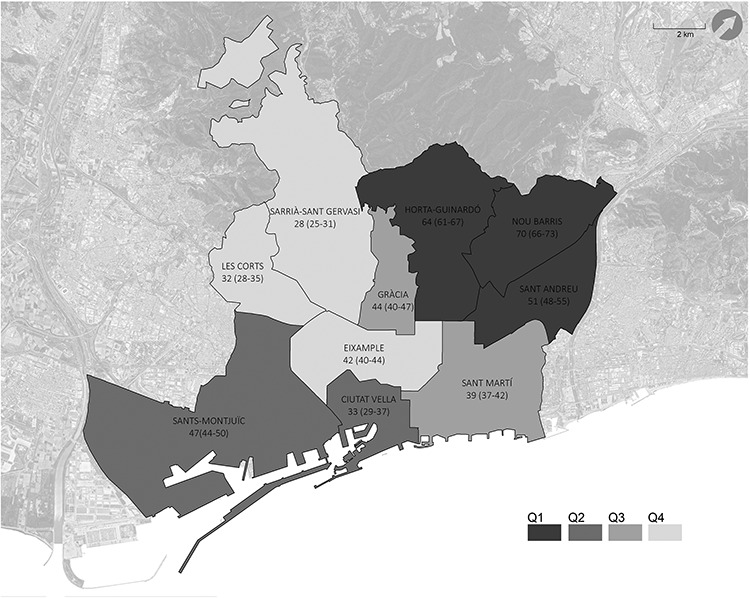

Our estimates showed an overall cumulative incidence rate in Barcelona of 49.24 cases per 10 000 inhabitants between 26 February 2020 (date of first reported case in the city) and 19 April 2020. The ecological analysis to assess case distribution by district found that the lower the mean income, the higher the COVID-19 incidence (Spearman rho = 0.83; P value = 0.003) (Fig. 1). The districts with the lowest per capita income had the highest incidence of COVID-19 per 10 000 inhabitants, whereas the districts with the highest mean income had the lowest incidence (Fig. 2). Specifically, the incidence rate in the most deprived district (Nou Barris) was 2.5 times higher than the district with the highest socioeconomic level (Sarrià-Sant Gervasi). There are two exceptions on the gradient, Sant Andreu and Ciutat Vella. The divergent results in the Sant Andreu district could be explained by the high percentage (25%) of residents younger than 25 years, who are less vulnerable to COVID-19. In the district of Ciutat Vella (‘Old City’), the results reflect the reality of this high-tourism area: low mean income in a relatively young population (>30% aged 25 to 39 years) and a high presence of non-resident foreign population (>25%). This also makes COVID-19 surveillance more difficult, as the public health system’s primary care settings are oriented to residents, while visitors would be served by emergency rooms and private clinics.

Fig. 1.

Average income and age-standardized incidence rates by district.

Fig. 2.

Map showing the 10 districts of Barcelona, classified by quartiles (Q) of mean income in euros (Q1 < 17 418; Q2 ≥ 17 418 and < 18 910; Q3 ≥ 18 910 and < 25 874; Q4 ≥ 25 874) and showing the age-standardized incidence rate (95% CI). Base layer extracted from icgc.cat.

Discussion

The COVID-19 incidence rate from 26 February 2020 to 19 April 2020 followed a socioeconomic gradient in Barcelona. Thus, the highest age-standardized incidence rate was observed in the most socioeconomically deprived district. This rate was 2.5 times greater than that observed in the district with the highest mean income. In addition, we observed a sustained and significant upward trend in the incidence of COVID-19 according to declining mean income by district.

Regarding our results, a report has shown substantial variation in the rates for COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths across the New York City boroughs. The Bronx—the borough with the highest proportion of racial/ethnic minorities, the most persons living in poverty and the lowest levels of educational attainment—had higher rates of hospitalization and death related to COVID-19.6 In a recent report of the UK Biobank, striking gradients in risk of hospitalization for COVID-19 were noted according to race and a metric of socioeconomic deprivation.12

Improvements in the health literacy of citizens, defined as people’s knowledge and capacity to obtain, process and understand health information and services to make appropriate health decisions, could help to reduce the risk of infection spreading and increase understanding of the need for social responsibility and adherence to disease prevention measures.19 Along this line, Zhong et al.8 showed that Chinese residents of relatively high socioeconomic status, and particularly women, had good knowledge, optimistic attitudes and appropriate practices towards COVID-19 during the initial rapid rise of the COVID-19 outbreak. In addition, racial disparities in knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding COVID-19 were described in the USA.9 Thus, understanding community risk and making decisions about community mitigation, including social distancing and strategic healthcare resource allocation, requires monitoring the numbers of COVID-19 cases, deaths and changes in incidence in small, well-characterized areas of the general population.20

Our results pointed out that efforts to contain an epidemic cannot ignore health equity issues. As the most deprived areas in Barcelona had the highest COVID-19 incidence, disease-control efforts should be more intensive in districts with the most marginalized and vulnerable population. In addition, ensuring equal treatment opportunities for all is key, but financial protection during outbreak also matters greatly.21 The link between poverty and disease has already been explored in depth. If this vicious cycle is not broken, local problems of health inequity will remain or could even be exacerbated in areas experiencing an epidemic.11 Previous studies have observed that the prevalence and severity of the COVID-19 pandemic is magnified because of the pre-existing epidemics of chronic disease,22,23 which also are socially patterned and associated with the social determinants of health.24,25 For instance, in a large cohort in Louisiana (USA), 76.9% of the patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and 70.6% of those who died were Black, whereas only 31% of this ethnic group receives routine health care. Black patients in that cohort had higher prevalence of obesity, diabetes, hypertension and chronic kidney disease at baseline than white patients.26

Bambra et al.6 point out the rise of a syndemic, defined as a set of closely intertwined and mutual enhancing health problems that significantly affect the overall health status of a population within the context of a perpetuating configuration of noxious social conditions. This concept is rooted in Dahlgren and Whitehead’s classic model of the determinants of health, which shows that individual lifestyles are embedded in social norms and networks and in living and working conditions, which in turn are related to the wider socioeconomic and cultural environment.27 Thus, inequalities in chronic conditions arise as a result of inequalities in exposure to the social determinants of health: the conditions in which people ‘live, work, grow and age’. These include working conditions, unemployment and access to essential goods and services (e.g., water, sanitation and food), housing and health care.6 Several plausible explanations can be suggested for the low rates observed in the districts with the highest socioeconomic level. First, the work environment mediates a large part of the social gradient in the incidence of several common cardiovascular risk factors as shown in the Gazele cohort. 28 The authors discuss the need to include working conditions in policies aimed to reduce social inequalities in health. According to the Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report, workers possessing higher levels of skills were significantly more likely to telework when the COVID-19 crisis generated lockdowns that completely changed the working arrangements for millions of workers. Although employers were encouraged to develop home-based teleworking, the likelihood of this option was lower for those without tertiary education, with limited numeracy and literacy skills, and lacking adequate access to technology. The pandemic also exacerbates existing labour market inequalities, and the extent to which these inequalities could further worsen amidst intensified technology adoption in the pandemic’s aftermath.29 As Hamidi et al.30 pointed out, commuter transportation systems are the most significant risk factor for the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, even greater than population density. A case study performed in Italy shows a direct relationship between daily cases and mobility choices in the preceding 21 days.31 Thus, workers with no possibility for home-based teleworking, many of them doing unskilled labour, were likely to have high-risk exposure during the pandemic. Finally, the strong links between housing and health could also be contributing to inequalities in COVID-19 incidence and outcome.6,32 Poor-quality housing is associated with overcrowding, which results in higher infection rates,33 and lower socioeconomic groups have increased exposure to poor-quality or insecure housing and therefore have a higher rate of negative health consequences.34 In our study, the use of second homes for the confinement period also could have contributed to the low rates observed in the more privileged districts of Barcelona.

Our study has several limitations. The results were standardized by age because individuals aged 65 and older are more vulnerable to COVID-19 infection; however, we assumed the age distribution of COVID-19 cases of the whole Spanish territory for our population area. Nonetheless, the distribution in Spain is similar to that of several other western European countries (e.g. Italy,35 Netherlands,36 Portugal 37 or Sweden 38); thus, the distribution in Barcelona is likely to be similar despite potential internal differences across Spain. In addition, the age distribution could differ between the city districts, particularly in Ciutat Vella, with its large population of foreign non-residents and tourists. Despite age-standardization, some residual confounding may exist in the incidence rate calculation, particularly in districts with a high percentage of younger residents (e.g. Sant Andreu and Ciutat Vella). The ecological nature of our analysis, using aggregated data, has intrinsic limitations because variation within districts (i.e. small areas) is not considered. More in-depth analysis should be considered to improve our knowledge on this topic and inform public health strategies for disease prevention.

Conclusion

The incidence of COVID-19 presented an inverse socioeconomic gradient in the city of Barcelona according to average income by district. Attention should be focused not only on care for people with the disease but also on devising a health strategy for the whole population that promotes and supports good public hygiene practices and health literacy, particularly adapted to the most deprived areas. Further studies are required to analyse whether the mortality from this infectious disease shows a similar pattern.

Funding

M.G. was sponsored by Carlos III Health Institute FEDER (CPII17/00012).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Oriol Baena for the assistance with the graphic plots and to Elaine Lilly PhD for the English review.

Jose Miguel Baena-Díez, Medical Doctor

Maria Barroso, Medical Doctor

Sara Isabel Cordeiro-Coelho, Medical Doctor

Jorge L. Díaz, Medical Doctor

María Grau, Medical Doctor, Doctor in Public Health

References

- 1. Peckham R. COVID-19 and the anti-lessons of history. Lancet. 2020;395:850–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (28 June 2020, date last accessed).

- 3. Vandoros S. Excess mortality during the Covid-19 pandemic: early evidence from England and Wales. Soc Sci Med. 2020;258:113101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ministry of Health - Spanish Government Update #152. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [Actualización n° 152. Enfermedad por el coronavirus (COVID-19)] https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov-China/documentos/Actualizacion_150_COVID-19.pdf (28 June 2020, date last accessed).

- 5. Chung RY, Dong D, Li MM. Socioeconomic gradient in health and the covid-19 outbreak. BMJ. 2020;369:m1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bambra C, Riordan R, Ford J, Matthews F. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Khalatbari-Soltani S, Cumming RG, Delpierre C, Kelly-Irving M. Importance of collecting data on socioeconomic determinants from the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak onwards. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhong BL, Luo W, Li HM et al. . Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:1745–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alobuia WM, Dalva-Baird NP, Forrester JD et al. . Racial disparities in knowledge, attitudes and practices related to COVID-19 in the USA. J Public Health (Oxf) 2020. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wadhera RK, Wadhera P, Gaba P et al. . Variation in COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths across New York City boroughs. JAMA. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lancet T. Redefining vulnerability in the era of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patel AP, Paranjpe MD, Kathiresan NP et al. . Socioeconomic deprivation, and hospitalization for COVID-19 in English participants of a national biobank. medRxiv 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.27.20082107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mahajan UV, Larkins-Pettigrew M. Racial demographics and COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths: a correlational analysis of 2886 US counties. J Public Health (Oxf) 2020. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Richardson SJ, Carroll CB, Close J et al. . Research with older people in a world with COVID-19: identification of current and future priorities, challenges and opportunities. Age Ageing 2020. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Interactive Map of COVID-19 Cases [Mapa interactiu de casos per ABS] http://aquas.gencat.cat/ca/actualitat/ultimes-dades-coronavirus/mapa-per-abs/ (28 June 2020, date last accessed).

- 16. Family Available Income per capita in Barcelona (2017) Distribució territorial de la renda familiar disponible per càpita a Barcelona (2017). https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/barcelonaeconomia/sites/default/files/RFD_2017_BCN.pdf (28 June 2020, date last accessed).

- 17. COVID-19 in Spain Report #26, April 27, 2020 [Informe sobre la situación de COVID-19 en España n° 26. 27 de abril de 2020]. https://www.isciii.es/QueHacemos/Servicios/VigilanciaSaludPublicaRENAVE/EnfermedadesTransmisibles/Documents/INFORMES/Informes%20COVID-19/Informe%20n%C2%BA%2026.%20Situaci%C3%B3n%20de%20COVID-19%20en%20Espa%C3%B1a%20a%2027%20de%20abril%20de%202020.pdf (28 June 2020, date last accessed).

- 18. Eurostat—your key to European statistics Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/

- 19. Xu C, Zhang X, Wang Y. Public health emergency, health literacy and social panic: mapping of COVID-19 based on the web search data. J Med Internet Res. 2020. doi: 10.2196/18831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. CDC COVID-19 Response Team Geographic differences in COVID-19 cases, deaths, and incidence - United States, February 12-April 7, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:465–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang Z, Tang K. Combating COVID-19: health equity matters. Nat Med. 2020;26:458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Uribarri A, Núñez-Gil IJ, Aparisi A et al. . Impact of renal function on admission in COVID-19 patients: an analysis of the international HOPE COVID-19 (Health Outcome Predictive Evaluation for COVID 19) Registry. J Nephrol. 2020. doi: 10.1007/s40620-020-00790-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koh J, Shah SU, Chua PEY et al. . Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of cases during the early phase of COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aguilar-Palacio I, Martinez-Beneito MA, Rabanaque MJ et al. . Diabetes mellitus mortality in Spanish cities: trends and geographical inequalities. Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(5):453–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sivén SS, Niiranen TJ, Aromaa A et al. . Social, lifestyle and demographic inequalities in hypertension care. Scand J Public Health. 2015;43(3):246–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Price-Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, Seoane L. Hospitalization and mortality among Black patients and White patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(26):2534–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dahlgren G, Whitehead M, European Strategies for Tackling Social Inequities in Health: Levelling up Part 2. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/103824/E89384.pdf (28 June 2020, date last accessed).

- 28. Meneton P, Hoertel N, Wiernik E et al. . Work environment mediates a large part of social inequalities in the incidence of several common cardiovascular risk factors: findings from the Gazel cohort. Soc Sci Med. 2018;216:59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Espinoza R, Reznikova L.. Who Can Log In? The Importance of Skills for the Feasibility of Teleworking Arrangements Across OECD Countries https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/3f115a10-en.pdf?expires=1593681356&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=90922E71CD060212E61E5ACFB2B30DCC (28 June 2020, date last accessed).

- 30. Hamidi S, Sabouri S, Ewing R. Does density aggravate the COVID-19 pandemic? J Am Plann Assoc. 2020; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cartenì A, Di Francesco L, Martino M. How mobility habits influenced the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the Italian case study. Sci Total Environ. 2020;741:140489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hernández D, Swope CB. Housing as a platform for health and equity: evidence and future directions. Am J Public Health. 2019;109:1363–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gibson M, Petticrew M, Bambra C et al. . Housing and health inequalities: a synthesis of systematic reviews of interventions aimed at different pathways linking housing and health. Health Place. 2011;17(1):175–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McNamara CL, Balaj M, Thomson KH et al. . The contribution of housing and neighbourhood conditions to educational inequalities in non-communicable diseases in Europe: findings from the European Social Survey (2014) special module on the social determinants of health. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27(suppl_1):102–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. National Institute of Health Istituto Superiore di Sanita. https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/ (28 June 2020, date last accessed).

- 36. National Institute for Public Health and the Environment Ministry of Health , Welfare and Sport [Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Spor]. https://www.rivm.nl/ (28 June 2020, date last accessed).

- 37. National Health Authority Direção-Geral da Saúde. https://www.dgs.pt/ (28 June 2020, date last accessed).

- 38. Folkhalsömyndigheten The Public Health Agency of Sweden. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/the-public-health-agency-of-sweden/ (28 June 2020, date last accessed).