In late May, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that the Americas have now become the epicentre of the global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, with Latin America having passed Europe and the USA in number of daily confirmed cases.1 Within Latin America, Brazil is currently taking the lead with the highest number of cases and deaths in the region. Although COVID-19 is a growing ongoing issue in Brazil, Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro does not seem very concerned with this major public health problem, having said ‘So what?’, when asked about the rapidly growing number of COVID-19 cases in the country.2

Social-control measures, medications and vaccines are key weapons against the pandemic.3 Before specific medications and vaccines are proven to be effective and can be used worldwide,4 social-control measures are still highly relevant in the fight against COVID-19.5 In this commentary, we aimed to explore the gaps in the COVID-19 response, by evaluating social distancing indicators and population mobility, and thus provide a better understanding about the evolving pandemic in Brazil and other countries in Latin America.

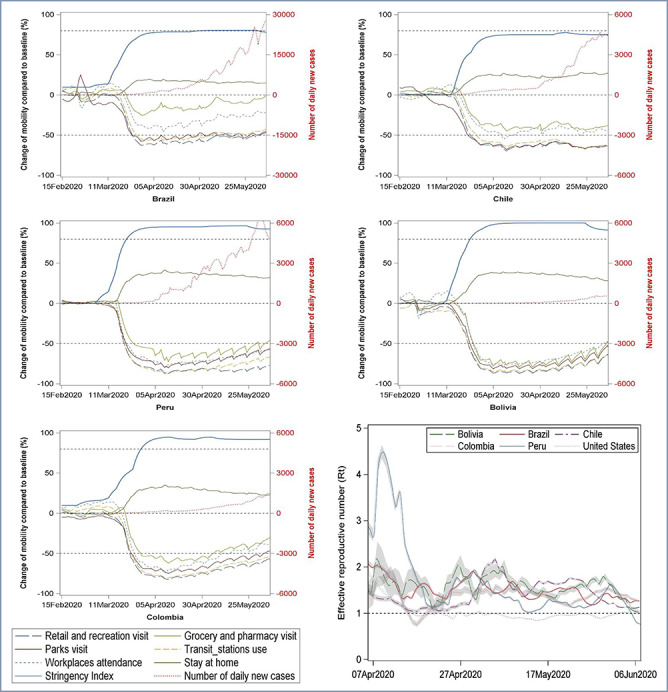

Based on the Stringency Index (SI) from The Coronavirus Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT)6 and COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports from Google (https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/),7 we calculated the daily new cases and real time effective reproductive number (Rt) for Brazil and other four countries (Chile, Bolivia, Colombia, Peru) in Latin America, as well as the Rt for the USA for comparison. Then, we plotted the trajectory of SI, daily new cases, Rt, and changes of six categories of community mobility for these five Latin American countries (Figure 1). The methodology is described in the Appendix available as Supplementary data at JTM online.

Figure 1.

The trajectory of SI, daily new cases, effective Rt, and changes of six categories of community mobility. (A serial interval with mean of 7.5 and a standard deviation of 3.4 days was used to calculate the Rt in window of 5 days. An exponentially weighted moving average method with parameter 0.3 was used to smooth time series of SI and number of daily new cases, and a base-10 log scale was used for the Y-axis for daily new cases)

From 11 March 2020 (the day when WHO declared COVID-19 as a pandemic), Brazil and the other four analysed countries all upgraded their SI to a high level to control the COVID-19 spread. In Brazil, the highest SI was 80 in late April. Under this SI, park visits, transit station use, and retail/recreation visits in Brazil declined by about 50%, while grocery/pharmacy visits decreased by less than 20%, and workplaces attendance decreased by less than 40%. Although the Rt in Brazil was below 2 after May, it maintains a high fluctuation between one and two, indicating a growing number of new cases. The response level and mobility pattern in Brazil was to some extent similar to the USA (Appendix available as Supplementary data at JTM online): a small decline in grocery/pharmacy visits and small increment in residential stay.

Compared to Brazil, Chile observed a similar SI level and mobility patterns’ change. Meanwhile, Peru, Bolivia and Colombia have upgraded to even higher SI (SI > 90) than Brazil. In these countries, mobility decreased by 50% or more for going out, while residential stay (i.e. stay at home) increased by at least 30%. Especially in Bolivia and Peru, the residential stay increased by 40%. The trend of Rt has decreased with time and was lower than or close to one in Peru and Bolivia respectively in early June. In Peru, this active and aggressive response reduced COVID-19 spread, as seen by a drop in Rt from 4.5 in early April to less than 1.0 in early June, and was a turning point in the pandemic evolution in this country.

As demonstrated in these SI and mobility analyses, Brazil is not doing very well in its response to COVID-19 pandemic. The small decline on grocery/pharmacy visits reflects the demand of daily necessities, including the need for medication refilling for existing long-term conditions. However, on the other hand, it may also reflect that numerous of people with symptoms are going to pharmacies to purchase medicines, without a medical assessment or prescription. Delays in seeking health services can increase the chance of spreading the virus to others. Furthermore, such delays in seeking care, may also result in more severe cases presenting to a healthcare facility, and therefore, burdening even more the already overstretched health system. Surprisingly, the workplace attendance only declined by less than 40% in Brazil, which implies there were still large numbers of people commuting to work every day rather than working from home, which might also have heightened the risk of transmission. A close evaluation of COVID-19 pandemic suggests important parallels in COVID-19 response between the USA and Brazil.

Besides, given the association between human mobility and the spread of infectious diseases, the large migration flows from Venezuela in Lain America may have aggravated the COVID-19 pandemic.8,9 Also, the decreasing vaccine coverage rates in Latin America over the last decade (such as in Brazil, Bolivia and Venezuela) has led to increased vulnerability of these countries to the COVID outbreak.10

Combining the SI and mobility reports would be a good way to examine the gaps between governments’ response. The extent of divergences between SI and mobility patterns’ changes reflect both the stringency level of a government’s response and the degree of compliance from citizens to these control measures. Leadership at the highest level of government is crucial in quickly averting the worst outcome of this pandemic.2 The rapidly evolving pandemic in Brazil and other countries in Latin America begs further attention globally, given its already weak stringency for responding to the current crisis. In the spirit of our findings, we therefore recommend immediate re-evaluation of COVID-19 response in Brazil to drastically change course of action on the ground.

Authors’ contributions

D.Z. conceived idea, conducted statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. S.R.M. contributed to the interpretation of the results and critical revision of the manuscript. X.H. contributed to the statistical analyses and critical revision of the manuscript. K.S. contributed to critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by The Startup Foundation for Scientific Research in Shandong University.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Boadle A. WHO Says the Americas are New COVID-19 Epicenter as Deaths Surge in Latin America. 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-latam/who-says-the-americas-are-new-covid-19-epicenter-as-deaths-surge-in-latin-america-idUSKBN2322G6 (18 June 2020, date last accessed).

- 2. Prado B. The L. COVID-19 in Brazil: so what? Lancet 2020; 395:1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Monto AS. Vaccines and antiviral drugs in pandemic preparedness. Emerg Infect Dis 2006; 12:55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lurie N, Saville M, Hatchett R, Halton J. Developing Covid-19 vaccines at pandemic speed. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:1969–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lai S, Ruktanonchai NW, Zhou L et al. . Effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions to contain COVID-19 in China. Nature 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hale T, Webster S, Petherick A, Phillips T, Kira B. Oxford COVID-19 Government Response racker. Oxford: Blavatnik School of Government, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aktay A, Bavadekar S, Cossoul G et al. . Google COVID-19 community mobility reports: anonymization process description (version 1.0). ArXiv 2020; abs/2004.04145. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Torres JR, Castro JS. Venezuela's migration crisis: a growing health threat to the region requiring immediate attention. J Travel Med 2019; 26:tay141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tuite AR, Thomas-Bachli A, Acosta H et al. . Infectious disease implications of large-scale migration of Venezuelan nationals. J Travel Med 2018; 25:tay077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fujita DM, Salvador FS, Nali L, Luna EJA. Decreasing vaccine coverage rates lead to increased vulnerability to the importation of vaccine-preventable diseases in Brazil. J Travel Med 2018; 25:tay100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.