Abstract

Objective

This study sheds light on the agenda-setting role of the media during the COVID-19 crisis by examining trends in nursing home (NH) coverage in 4 leading national newspapers—The New York Times, Washington Post, USA Today, and Los Angeles Times.

Method

Keyword searches of the Nexis Uni database identified 2,039 NH-related articles published from September 2018 to June 2020. Trends in the frequency of NH coverage and its tone (negative) and prominence (average words, daily article count, opinion piece) were examined.

Results

Findings indicate a dramatic rise in the number of NH articles published in the months following the first COVID-19 case, far exceeding previous levels. NH coverage became considerably more prominent, as the average number of words and daily articles on NHs increased. The proportion of negative articles largely remained consistent, though volume rose dramatically. Weekly analysis revealed acceleration in observed trends within the post-COVID-19 period itself. These trends, visible in all papers, were especially dramatic in The New York Times.

Discussion

Overall, findings reveal marked growth in the frequency and number of prominent and negative NH articles during the COVID-19 crisis. The increased volume of coverage has implications for the relative saliency of NHs to other issues during the pandemic. The increased prominence of coverage has implications for the perceived importance of addressing pre-existing deficits and the devastating consequences of the pandemic for NHs.

Keywords: Agenda-setting, Coronavirus, Long-term care, Newspapers

Long-term care (LTC) is the ugly stepchild of health policy. It is widely understood that the overall quality of nursing home (NH) care needs improvement, and that the sector is inadequately financed and ineffectively regulated (Werner et al., 2020; Wiener et al., 2007). Yet, with exceptions such as the 1987 NH Reform Act and NH transparency provisions within the 2010 Affordable Care Act (Wells and Harrington, 2013; Wiener et al., 2007), government has failed to act due to the low political salience of the issue, which remains beneath the radar of most Americans. This low level of concern has been reflected in (and partially enabled by) low media coverage of NH-related issues. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has turned all of this on its head: NHs have become a leading story.

In the early response to COVID-19, NHs were an afterthought. Initially, the focus was to ensure that hospitals were well prepared, and that they did not function as a site for spreading infection. This focus on hospitals explains some of the decisions that ultimately had a negative effect on NHs, such as in California, New Jersey, and New York where NHs were required to accept individuals newly discharged from hospitals regardless of COVID-19 status; the goal was to ensure that hospital beds would be available (Barker and Harris, 2020).

However, the potential of NHs to act as superspreaders—both within individual NHs and in the community—increasingly became apparent. The first known COVID-19 case in the United States, a Seattle area man recently returned from a visit to Wuhan, China, was made public on January 21, 2020 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020). On February 29, 2020, the Washington State Public Health Department announced the death of a man, later revealed to be a resident of the Life Care Center of Kirkland, Washington. Two days later, the news identified the facility and reported the deaths of “at least three residents” and widespread infection in other residents and staff (Feuer and Higgins-Dunn, 2020). And yet, the federal government response to this emerging threat in NHs was slow and ineffective. By the end of May, COVID-19 deaths associated with NHs stays reached about 40,600, roughly 40% of all COVID-19 deaths—a likely underestimate, due to inconsistent and unreliable testing and reporting across states (Kwiatkowski et al., 2020). NHs are indeed “ground zero” of the COVID-19 pandemic (Barnett and Grabowski, 2020).

This study documents the rising prevalence of NH coverage in the national media in the wake of COVID-19. It reports an analysis of NH articles from The New York Times, Washington Post, USA Today, and Los Angeles Times from September 2018 to June 2020. These newspapers constitute four of the six most widely circulated dailies in the United States (Cision Media Research, 2019). Results reveal marked increases both in the volume of NH articles and in the number of prominently placed articles with negative tone, post-COVID-19.

Method

All NH articles published in the four newspapers from September 1, 2018 to June 6, 2020 were retrieved from the Nexis Uni database (formerly LexisNexis Academic). Search terms included “NH”/“NHs,” “LTC facility”/“LTC facilities,” and “nursing facility”/“nursing facilities.” Duplicates, obituaries, advertisements, and irrelevant articles (e.g., NHs as election sites) were excluded, leaving 2,039 of 2,677 articles identified for analysis.

Each article was characterized based on information generated by Nexis Uni and article review. The day, month, and year of publication were recorded; so too was the tone of a story as determined by a LexisNexis algorithm that identifies significant levels of negative language (LexisNexis, 2017). Prominence refers to the relative visibility or importance granted to a particular topic or story. It was measured using the number of words; article type, that is, editorial/column/op-ed (opinion) versus other; and total number of NH articles published on the same day.

Frequencies and descriptive statistics were used to describe article content. Cross-tabulations, Pearson χ 2-tests, t tests, analyses of variance (ANOVAs), and graphing were used to describe relationships among variables. Trends were examined monthly (September 1, 2018–May 31, 2020), weekly (February 1, 2020–June 6, 2020), and pre- versus post-COVID-19 (September 1, 2018—January 31, 2020 vs February 1, 2020–June 6, 2020).

Results

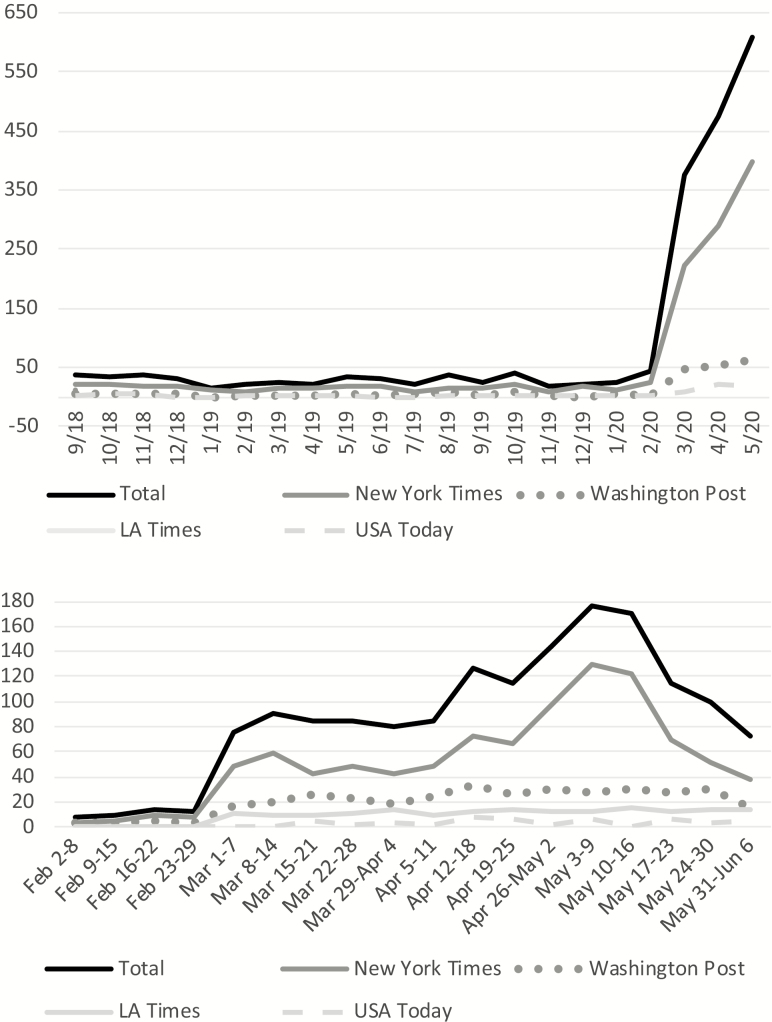

Findings indicate a dramatic rise in the number of NH articles published in the months following the first COVID-19 case, far exceeding previous levels (Figure 1A). Total articles jumped from less than 50 monthly to 375, 475, and 610, respectively, during March, April, and May 2020. More than three-quarters of the NH articles identified were published in the 4-month post-COVID period (February 1, 2020–June 6, 2020) as compared to one-quarter in the previous 17 months (September 1, 2018—January 31, 2020) (Table 1). This trend, visible in all newspapers, was especially dramatic in The New York Times, which constituted 54.8% of articles pre-COVID-19 and 61.8% post-COVID-19 (p < .05) (Table 1). Weekly data reveal rapid acceleration in NH coverage after February 1, with a steep rise in articles peaking at 177 during May 3–9 before declining to 73 during May 31–June 6 as other issues, notably Black Lives Matter, increasingly competed with COVID-19 for the attention of the mass media and the general public (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Volume of nursing home coverage by newspaper. (A) By month: September 2018–May 31, 2020 (n = 1,979). (B) By week: February 1, 2020–June 6, 2020 (n = 1,563).

Table 1.

Number and Proportion of Nursing Home Articles Pre- vs Post-COVID-19 by Article Characteristic (n = 2,039)

| Pre-COVID-19 | Post-COVID-19 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | (September 1, 2018–January 31, 2020) | (February 1, 2020–June 6, 2020) | χ 2-statistic (df), t-statistic, p-value | |

| % (n)/M (SD) | % (n)/M (SD) | % (n)/M/(SD) | ||

| Newspaper | ||||

| New York Times | 60.2% (1,227) | 54.8% (261) | 61.8% (966) | 8.836 (3), <.032 |

| Washington Post | 24.4% (498) | 27.5% (131) | 23.5% (367) | |

| LA Times | 11.5% (235) | 12.4% (59) | 11.3% (176) | |

| USA Today | 3.9% (79) | 5.3% (25) | 3.5% (54) | |

| Negative tone | 28.4% (579) | 32.1% (153) | 27.3% (426) | 4.287 (1), <.038 |

| Opinion | 10.0% (203) | 10.5% (50) | 9.8% (153) | 0.208 (1), .208 |

| Daily number of articles | 7.89 (7.98) | 1.48 (.91) | 9.84 (8.15) | 23.339, <.001 |

| Number of words | 1781.57 (1373.84) | 1407.22 (1006.52) | 1895.57 (1448.73) | 6.886, <.001 |

| Total | 100% (2,039) | 23.3% (476) | 76.7% (1,563) |

Although a significantly higher proportion of NH articles had negative tone pre-COVID-19 (p < .05), the overall difference from the post-COVID-19 period was substantively small (32.1% vs 27.3%) (Table 1). Moreover, the volume of negative coverage became considerably larger and more concentrated post-COVID-19 (153 articles over 17 months pre-COVID-19 versus 426 articles over 4 months post-COVID-19) (Table 1). In addition, NH coverage became considerably more prominent; on average, the number of words and daily articles increased by close to 500 (p < .001) and 8.5 (p < .001), respectively, between the pre- and post-COVID-19 periods (Table 1). By contrast, the proportion of opinion pieces hovered around 10% throughout (p > .05). Weekly data reveal variation in tone (p < .001), words (p < .001), and articles (p < .001) post-COVID-19, with coverage being especially prominent from the end of April through the middle of May and negative tone peaking at several points during the news cycle (Table 2).

Table 2.

Weekly Number and Proportion of Nursing Home Articles by Tone and Prominence during COVID-19 (n = 1,563)

| Negative tone | Opinion piece | Number of words | Number of articles | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | M/(SD) | M/(SD) | |

| February 2–8 | 12.5% (1) | 12.5% (1) | 1151.00 (361.04) | 1.50 (.54) |

| February 9–15 | 22.2% (2) | 22.2% (2) | 1421.67 (806.81) | 1.78 (.44) |

| February 16–22 | 35.7% (5) | 7.1% (1) | 1630.14 (1103.37) | 2.43 (1.28) |

| February 23–29 | 7.7% (1) | 15.4% (2) | 1382.69 (966.88) | 2.38 (1.33) |

| March 1–7 | 7.9% (6) | 5.3% (4) | 1639.45 (754.14) | 5.50 (2.92) |

| March 8–14 | 15.6% (14) | 8.9% (8) | 1564.11 (670.70) | 7.20 (3.96) |

| March 15–21 | 32.1% (27) | 11.9% (10) | 1574.06 (739.19) | 5.71 (2.55) |

| March 22–28 | 29.4% (25) | 9.4% (8) | 1514.-08 (760.86) | 5.73 (2.65) |

| March 29–April 4 | 38.8% (31) | 7.5% (6) | 1869.51 (1667.03) | 5.13 (2.88) |

| April 5–11 | 26.2% (22) | 11.9% (10) | 1946.99 (1518.81) | 6.55 (3.30) |

| April 12–18 | 36.2% (46) | 7.9% (10) | 1797.35 (1536.42) | 9.03 (4.61) |

| April 19–25 | 26.3% (30) | 7.9% (9) | 2142.25 (1858.33) | 8.89 (6.38) |

| April 26–May 2 | 20.8% (30) | 10.4% (15) | 2229.85 (1631.90) | 15.19 (9.90) |

| May 3–9 | 44.6% (79) | 10.7% (19) | 2060.97 (1414.821) | 16.12 (9.55) |

| May 10–16 | 10.0% (17) | 7.6% (13) | 2195.48 (1571.78) | 17.48 (10.82) |

| May 17–23 | 27.0% (31) | 15.7% (18) | 1827.50 (1351.02) | 10.13 (7.16) |

| May 24–30 | 36.0% (36) | 11.0% (11) | 1871.12 (1876.50) | 6.27 (2.90) |

| May 31–June 6 | 31.5% (23) | 8.2% (6) | 1804.19 (1536.10) | 4.56 (2.40) |

| Total | 27.3% (426) | 9.8% (153) | 1895.57 (1448.73) | 9.84 (8.15) |

| χ 2/F (df), p-value | 96.39 (17), <.001 | 12.36 (17), .778 | 2.64 (17), <.001 | 45.85 (17), <.001 |

Discussion

Our findings reveal marked growth in the frequency and prominence of NHs across four national newspapers during COVID-19. These findings are consistent with previous research documenting annual fluctuations in NH coverage from 1999 to 2008, the last time period in which trends in NH coverage were systematically examined (Miller, Tyler, Rozanova, and Mor, 2012; Miller, Livingstone, and Ronneberg, 2017). The prevalence and portrayal of NHs is important due to the critical role the media plays in influencing how the public perceives a topic or issue (Bryant and Oliver, 2008). The pandemic can be seen as a “focusing event,” framing the issue of NH quality as a policy problem and directing the public’s attention to it (Kingdon, 1995). The barrage of stories can thus “prime” the public for further action on NHs, creating the conditions necessary for raising the issue on the policy agenda (Scheufele and Tewksbury, 2007).

Public attitudes towards NHs originate directly from personal experience, but also indirectly through the way NHs are portrayed in mass media (Kaiser Family Foundation [KFF], 2001, 2005). Furthermore, anecdotal and case study evidence suggests that the media has influenced NH policy, both in the United States and internationally, since the early-1970s (Smith, 1981; Lloyd et al., 2014; Wiener et al., 2007). This study’s findings suggest that both first- and second-order agenda-setting effects may be playing out with respect to media coverage of NHs during COVID-19. First-order agenda-setting pertains to the way in which the volume of coverage influences the public’s ranking of the relative importance of the issue; second-order effects pertain to how the framing of coverage influences the public’s perception of the issue (Dearing and Rodgers, 1996; McCombs, 2014).

This study documents a rapid increase in NH articles, with implications for the comparative salience of NHs to other issues during the pandemic. This dramatic spike in NH coverage is consistent with spikes during the 1970s, due to criminal activity by investors and operators (Smith, 1981), and in 2005, due to deaths stemming from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita (Miller et al., 2012), both of which can be tied to a subsequent policy response. There can be no doubt that the breadth of reporting on NHs during COVID-19 will have a lasting impression on the increased salience of NH policy for years to come.

While the increased volume of NH coverage is remarkable, the framing of this coverage is also important to note. Framing refers to how specific issues/topics come to be perceived by the public due to the way that the media portrays them (Ghanem, 1997; Scheufele and Tewksbury, 2007). Changes in framing include the increased prominence of coverage documented in this study. It also includes the increased volume of negative stories, particularly with respect to the devastating consequences of the pandemic for NH residents, staff, operators, families, and communities, thereby raising awareness of the inadequate government response to the pandemic in NHs and shining a light on well-established, ongoing deficits in NH performance and oversight.

Heightened media coverage has implications for how the public perceives NHs. The general public has long viewed NHs unfavorably (Jones and Saad, 2019; KFF, 2007). Evidence suggests, however, that public views have become increasingly more negative as awareness of COVID-19 and systemic challenges facing the NH sector have grown and the need for government action has become more acute. One national poll found that 54% of respondents had a worse opinion of NHs in the wake of COVID-19, compared to 43% who reported no change in opinion and just 3% whose opinion grew more favorable (Spanko, 2020). This poll also documents the general belief that government had not done enough to support NHs. Other polls find strong public support for requiring facilities to publicly disclose active COVID-19 cases and to make video visitations available, and for government to fund additional PPE, testing, and staffing to bolster the industry’s response (GS Strategy Group, 2020; Keenan et al., 2020).

This study has several limitations. First, the findings may not be generalizable to other newspapers or media (e.g., TV, digital), nor beyond the time period studied. Second, other potentially suggestive dimensions were not examined, but could be in future, given additional time and resources: for example, location (front page or section vs other), photographs/images, and specific topics addressed. Third, evaluation of tone by trained coders may have resulted in different assessments than the LexisNexis algorithm. Fourth, in-depth qualitative analysis may permit more nuanced examination of the coverage reported.

Conclusion

The coronavirus pandemic has laid bare many systemic problems in the United States—from structural racism, poverty, and inadequate access to health care—and those endemic to NHs are no exception. Our findings demonstrate that the large number of deaths in NHs, in the United States and across the world, has increased media attention to this issue, and appear to have influenced public attitudes toward these institutions. This increased attention to the ongoing poor quality and oversight of NHs, which so importantly contributed to the high number of deaths, may function as a focusing event that frames subsequent policy.

Funding

None declared.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Author Contributions

E.A. Miller made substantial contributions to the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript, and final approval of the version submitted. E. Simpson made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data, preparation of the manuscript, and final approval of the version submitted. P. Nadash made substantial contributions to the interpretation of data, preparation of the manuscript, and final approval of the version submitted. M. Gusmano made substantial contributions to the interpretation of data, preparation of the manuscript, and final approval of the version submitted.

References

- Barker K., & Harris A. J. (2020, April 23). “Playing Russian Roulette”: Nursing homes told to take the infected. The New York Times Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/24/us/nursing-homes-coronavirus.html

- Barnett M. L., & Grabowski D. C. (2020, March 24). Nursing homes are ground zero for COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum Retrieved from https://jamanetwork.com/channels/health-forum/fullarticle/2763666 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bryant J., & Oliver M. B. (Eds.). (2008). Media effects: Advances in theory and research. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020, January 21). First travel-related case of 2019 coronavirus detected in United States. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0121-novel-coronavirus-travel-case.html [Google Scholar]

- Cision Media Research (2019, January 4). Top-ten U.S. daily newspapers. Media Blog Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20190722203322/https://www.cision.com/us/2019/01/top-ten-us-daily-newspapers

- Dearing J.W., & Rogers E. A (1996). Agenda setting. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Feuer W., & Higgins-Dunn N. (2020, March 2). Seattle-area officials report new coronavirus deaths, bringing U.S. total to 6. CNBC Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/02/seattle-area-officials-report-3-new-coronavirus-deaths-bringing-us-total-to-5.html [Google Scholar]

- Ghanem S. (1997). Filling in the tapestry: The second level of agenda setting. In McCombs M., Shaw D. L., & Weaver D. (Eds.), Communication and democracy: Exploring the intellectual frontiers in agenda-setting theory (pp. 3–14). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- GS Strategy Group (2020, May). Public Opinion Survey: COVID-19 impact on nursing homes and assisted living communities Retrieved from https://www.ahcancal.org/News/news_releases/Documents/Survey-Summary-COVID-LTC.pdf

- Jones J., & Saad L. (2019, December). Gallup News Services, December Wave One—Final Topline. Retrieved from http://news.gallup.com/file/poll/274751/200106HonestyEthics.pdf

- Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) (2001, October). National survey on nursing homes. Author; Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/other/poll-finding/kaisernewshour-survey-on-nursing-homes/ [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). (2005, June). May/June health poll report survey. Author; Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/medicare/poll-finding/mayjune-2005-kaiser-health-poll-report-toplines/ [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) (2007, November 29). Update on the public’s views of nursing homes and long-term care services—toplines. Author; Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/other/poll-finding/update-on-the-publics-views-of-nursing/ [Google Scholar]

- Keenan T. A., Rainville C. & Love J. (2020, April). Coronavirus study: Advocacy issues. AARP Research; Retrieved from https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/surveys_statistics/health/2020/coronavirus-study-advocacy.doi.10.26419-2Fres.00385.001.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon J. W. (1995). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. 2nd ed.Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski M., Nadolny T. L., Priest J., & Stucka M. (2020, June 1). “A National Disgrace”: 40,600 deaths tied to US nursing homes.” USA Today Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/investigations/2020/06/01/coronavirus-nursing-home-deaths-top-40–600/5273075002/

- LexisNexis. (2017, September 25). Discover new combined sources for negative news and English-language news Retrieved fromhttps://www.lexisnexis.com/infopro/keeping-current/ln-info-professional-update/b/lnpu/archive/2017/09/25/discover-new-combined-sources-for-negative-news-and-english-language-news.aspx

- Lloyd L., Banerjee A., Harrington C., Jacobsen F. F., & Szebehely M (2014). It is a scandal! Comparing the causes and consequences of nursing home media scandals in five countries. International Journal of Sociology & Social Policy, 34(1/2), 2–18. [Google Scholar]

- McCombs M. (2014). Setting the agenda: The mass media and public opinion. 2nd ed Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller E. A., Livingstone I., & Ronneberg C. R. (2017). Media portrayal of the nursing homes sector: A longitudinal analysis of 51 U.S. newspapers. The Gerontologist, 57(3), 487–500. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E. A., Tyler D., Rozanova J., & Mor V. (2012). National newspaper portrayal of U.S. nursing homes: Periodic treatment of topic and tone. The Milbank Quarterly, 90(4), 725-761. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00681.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheufele D. A., & Tewksbury D (2007). Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 9–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00326.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D.B. (1981). Long-term care in transition: The regulation of nursing homes. BeardBooks. [Google Scholar]

- Spanko A. (2020, May 28). Public opinion of nursing homes takes COVID-19 hit, but most think government didn’t do enough. Skilled Nursing News. Retrieved from https://skillednursingnews.com/2020/05/public-opinion-of-nursing-homes-takes-covid-19-hit-but-most-think-government-didnt-do-enough/

- Wells J., & Harrington C. (2013, January 28). Implementation of Affordable Care Act provisions to improve nursing home transparency, care quality, and abuse prevention. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/8406.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Werner R. M., Hoffman A. K., & Coe N. B (2020). Long-term care policy after Covid-19—solve the nursing home crisis. The New England Journal of Medicine. May 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2014811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener J. M., Freiman M. P., & Brown D.(2007, December). Nursing home care quality; twenty years after the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; Retrieved January 17, 2018, from http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7717.pdf [Google Scholar]