The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted all aspects of health care delivery. To protect health care workers and patients across the country from the risk of disease transmission, rules, regulations and reimbursement policies were altered to enable widespread use of telecommunications technology in lieu of in-person clinical visits.1 As a result, the delivery of rehabilitation in many settings was drastically and suddenly altered with physical therapists utilizing telehealth modalities in new ways and with new populations.2 The shift to telerehabilitation provides a tremendous learning opportunity. This point of view provides an overview of how a learning health care system (LHS) approach to the study of telerehabilitation can promote innovation in optimal health care delivery and fuel new scientific discovery.

Background

Telehealth is a broad umbrella of modalities that includes nonclinical and clinical services.3Telerehabilitation refers specifically to clinical rehabilitation services with the focus of evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment. Telerehabilitation can be provided in a variety of ways, including 2-way real-time visits with audio, video, or both; asynchronous e-visits; virtual check-ins; remote evaluations of recorded videos or images; and telephone assessment and management services. The Department of Veterans Affairs was an early adopter of telerehabilitation, with use of remote services (including physical therapy) rapidly accelerating even prior to the pandemic.4 Until precautions related to COVID-19 created a need for safer service delivery options, the uptake of telerehabilitation in other health systems and across the country was hampered by variation and restrictions in state regulations and reimbursement policies of Medicare and private insurers.5 Recent changes in rules, regulation, and reimbursement now allow the use of telerehabilitation for physical therapy in some circumstances, providing unprecedented research opportunities to study the implementation and outcomes of telerehabilition.

Several systematic reviews conclude that telerehabilitation is effective for patients with musculoskeletal conditions, multiple sclerosis, osteoarthritis, and recovery of motor function.6,7–9 Some studies suggest that telerehabilitation can also reduce health care costs, improve treatment adherence, improve physical and mental function and quality of life, and be delivered in a manner that is satisfactory to patients.10–12 Most of the telerehabilitation studies address outcomes of synchronous, real-time time rehabilitation, although there is some evidence that asynchronous telemedicine can also be effective for specific patient populations, such as those following total joint replacement.13 More robust studies are needed to address questions about the feasibility, safety, and effectiveness of telerehabilitation modalities across subgroups of patient populations and settings, such as those who are frail or at risk of falling.

Care delivery changes resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic offer key opportunities for LHS research. The LHS approach harnesses the power of data and analytics to learn what works best and to feed that knowledge back to patients, clinicians, other professionals, and stakeholders to create a continuous quality improvement cycle.14 Thus, an LHS systematically integrates evidence established with internal data and real-world experience as part of usual care in order to provide high-quality, safer, more efficient care.15 The iterative learning that is inherent in an LHS can help us quickly understand when, how, and if it is appropriate to use the different forms of technology for delivery of physical therapy. Research in an LHS is situated within the context and infrastructure of health care delivery, which varies by service, setting, and population served. LHS research embraces stakeholder involvement and innovative study designs and leverages real-world care delivery processes.16 Designing and conducting research as part of clinical practice not only will accelerate the acquisition of evidence on telerehabilitation with easier-to-translate findings but will also assist in identifying best practices for rehabilitation that are more likely to be adopted and scaled up both during and after the pandemic subsides.

A Learning Health System Approach to Telerehabilitation

Recommendations from the Learning Health Systems Task Force of AcademyHealth, tailored for telerehabilitation, provide a set of research priorities in response to the pandemic.17 The task force called for rapid-cycle research that supports learning within health systems, uses rigorous methods, and is responsive to and driven by the questions of health system leaders and key stakeholders. Rapid-cycle research typically is done in a brief period and includes multiple cycles of small changes to address a problem.18 Six priority domains for rapid-cycle evaluations in LHS were identified: care delivery, coordination, information and technology, patients and communities, workforce, and policy.17

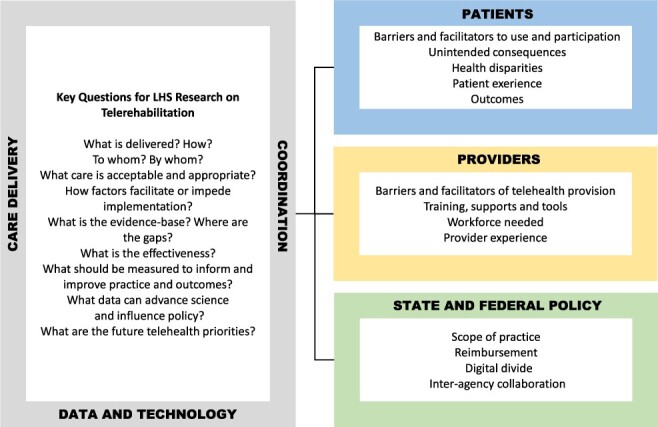

With the shift to telerehabilitation, there are benefits to research focusing on each of these domains as they pertain to telerehabilitation independently as well as to studying the intersection among domains. In the Figure, we provide examples of research questions on telerehabilitation that are situated at the intersection of care delivery, care coordination, data, and technology, and we illustrate questions that stem from this intersection that are specific to patients, providers, and policy. There are many opportunities for research across domains that can be used to improve care and outcomes, and advance the science supporting telerehabilitation. A variety of research approaches and methodologies can be used to address these questions depending on a health system’s capacity, culture, and readiness to align data, informatics, science, practice, providers, and patients as partners.

Figure.

Priorities and key questions for learning health systems evaluation of telerehabilitation.

Research on real-world practice is imperative to understand the reach and implementation of telerehabilitation and to quantify how much and what types of telerehabilitation are being delivered, to whom, and by whom. Quantitative researchers using administrative and claims data can conduct descriptive studies to examine how policy changes have impacted the delivery of rehabilitation and telerehabilitation modalities. For example, researchers can examine the utilization of telerehabilitation codes before the pandemic, and track how that utilization changed after release of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services waivers allowing telerehabilitation. Data scientists working with clinical data within a health system can generate real-time reports of practice in order to drive improvements and address disparities. Leveraging existing data, such as electronic health record or Medicare claims data, is a critical first step in quantifying policy influence on implementation, use by providers and the impact of telerehabilitation on patient outcomes. These types of descriptive studies must be informed by a thorough understanding of the changing federal and state rules for practice and reimbursement and draw upon standardized data elements for coding care delivery, health status, and outcomes, including functional outcomes and other important outcomes such as injurious falls and hospital readmissions. Research studies focusing on outpatient physical therapy delivery in health systems that utilize standardized patient reported outcome measures could compare outcomes of specific subgroups of patients (those with specific diagnoses or conditions) receiving usual care to those receiving telerehabilition.

Studying variation is also incredibly informative. At the system level, examining telerehabilitation delivery over time and across geographic areas can demonstrate if and how utilization by providers and patients was differentially affected by the pandemic, stay at home orders and availability of internet or broadband. This analysis creates important opportunities for health system and public health collaboration and interagency policy changes to address access. Evaluating provider-level data can help identify “super-users” or telerehabilitation champions and the factors—such as care coordination and provider training and equipment—that facilitate use for some or are barriers to be addressed for others. Patient-level analyses can identify unintended disruptions or delays in care and explore patient experience, including satisfaction with, confidence in, and perceived acceptability of technology for treatment and engagement with the health care team. An LHS approach to longitudinal analysis of telerehabilitation throughout the pandemic can provide meaningful data for continuous improvement and innovation and help guide decisions as to which modalities for which patients should be sustained over time and after the pandemic ends. For example, analyses of data from practice can identify clinical subgroups that have not been reached or fully engaged using telerehabilitation. Such data could inform efforts to improve access and the format, content, and delivery of treatment via telerehabilitation. Analysis of data concurrent with care delivery can measure the effect of changes as they are implemented. This rapid-cycle research can be done iteratively during the pandemic, providing opportunities to use data from practice to improve care. These studies will generate new knowledge as part of practice at a time when care delivery, policy, and payment reform are changing, which provides an opportunity to address issues in access to and disparities in telerehabilitation in a timely manner.

Descriptive studies of telerehabilitation implementation and use set the stage for outcomes research. Such studies are needed across the range of rehabilitation settings where telerehabilitation has proliferated and where it has faltered. Although randomized clinical trials on the provision of telerehabilitation are nearly impossible in current circumstances, strong evidence on effectiveness of telerehabilitation can be obtained from well-designed observational studies that compare outcomes of patients treated using telerehabilitation to outcomes of historic controls who were treated by traditional care prior to the pandemic.

The effect of using telerehabilitation for treatment is likely to vary by patient condition and severity. Inherent in observational research is the likelihood of a significant amount of unmeasured confounding and potentially missing data due to the challenges of care delivery during COVID-19. It will be important that these types of studies examine common patient conditions and utilize appropriate analytic methods to control for severity, comorbidities, and other patient characteristics affecting care. Such methods include risk adjustment techniques (eg, use of propensity scores and control for potential confounders in models), controls for selection bias (eg, use of inverse probability of treatment weighting and instrumental variables), imputation for missing data, and other approaches common to health services research.19,20 Early research with sufficiently powered samples will begin to identify subgroups of patients that might or might not benefit from specific types of telerehabilitation modalities. These data will be essential for decision making about sustaining telerehabilitation services. With sufficient planning to consider equipoise in care delivery, available capacity for research in practice during or after the pandemic, and appropriate methodological expertise, more rigorous study designs including pragmatic trials and hybrid implementation-effectiveness studies should be considered. Ultimately, if telerehabilitation interventions can yield outcomes equivalent to those of usual care and are equally or more cost-effective, there would be strong evidence in support of sustaining telerehabilitation as a care delivery option after the pandemic subsides.

Seize the Opportunity

The new normal for rehabilitation services after COVID-19 is likely to include some amount of telerehabilitation in different forms in different health systems. The continuous learning within an LHS is as important to the local system as it is to the external community of practice and science.21 This Point of View was designed to stimulate discussions on rapid evaluation and learning about telerehabilitation within health systems through the use of existing data collection systems, such as electronic health records and claims and administrative data. There are also opportunities for external funding that could be leveraged to support studies of the health care system response with telerehabilitation and the related outcomes. Funders including the VA Health Services Research & Development, National Institutes of Health, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) are supporting research on care delivery in the era of COVID-19 with special calls for proposals. Beyond the pandemic, researchers, health care professionals, and patients as partners have the opportunity to continue engagement with these funding agencies for targeted proposals on telerehabilitation implementation research. By addressing each of the domains identified—care delivery, coordination, data and technology, patients, workforce, and policy—there is incredible potential for LHSs to improve the quality and efficiency of telerehabilitation and advance the evidence where knowledge gaps persist. Dissemination of research findings will be critical; shared experiences and findings across health systems have the potential to move the rehabilitation community forward and establish a stronger foundation for the provision of telerehabilitation. We call for rehabilitation researcher-health systems partnerships to seize these opportunities by being part of this rapid response research and establishing the foundation for longer-term studies to advance care, outcomes, science and policy.

Author Contributions

Concept/idea/research design: J. Prvu Bettger, L.J. Resnik

Writing: J. Prvu Bettger, L.J. Resnik

Data collection: L.J. Resnik

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): J. Prvu Bettger, L.J. Resnik

Funding

Aspects of this work were supported through a grant from the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research, National Institute on Nursing Research (1 P2C HD101895-01), and from the US Department of Health and Human Services and National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging (1P30AG064201-01).

Disclosures

The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Janet Prvu Bettger, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Duke University School of Medicine, and Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina.

Linda J Resnik, Department of Health Services, Policy and Practice, School of Public Health, Brown University; and Providence VA Medical Center, Providence, RI.

References

- 1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers for Health Care Providers 2020; https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2020.

- 2. American Physical Therapy Association . Impact of COVID-19 on the Physical Therapy Profession: A Report From the American Physical Therapy Association. Arlington, VA, USA; June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3. NEJM Catalyst . What is Telehealth? [Brief Article]. NEJM website. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0268. 2018. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cowper-Ripley DC, Jia H, Wang X, et al. Trends in VA telerehabilitation patients and encounters over time and by rurality. Fed Pract. 2019;36:122–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bierman RT, Kwong MW, Calouro C. State occupational and physical therapy telehealth laws and regulations: a 50-state survey. Int J Telerehabil. 2018;10:3–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cottrell MA, Galea OA, O'Leary SP, Hill AJ, Russell TG. Real-time telerehabilitation for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions is effective and comparable to standard practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31:625–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Agostini M, Moja L, Banzi Ret al. Telerehabilitation and recovery of motor function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21:202–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grona SL, Bath B, Busch A, Rotter T, Trask C, Harrison E. Use of videoconferencing for physical therapy in people with musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24:341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yeroushalmi S, Maloni H, Costello K, Wallin MT. Telemedicine and multiple sclerosis: a comprehensive literature teview. J Telemed Telecare. 2019; 1357633X19840097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sanford JA, Griffiths PC, Richardson P, Hargraves K, Butterfield T, Hoenig H. The effects of in-home rehabilitation on task self-efficacy in mobility-impaired adults: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1641–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Prvu Bettger J, Green CL, Holmes DNet al. Effects of virtual exercise rehabilitation in-home therapy compared with traditional care after total knee arthroplasty: VERITAS, a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102:101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tousignant M, Boissy P, Corriveau H, Moffet H. In home telerehabilitation for older adults after discharge from an acute hospital or rehabilitation unit: a proof-of-concept study and costs estimation. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2006;1:209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bini SA, Mahajan J. Clinical outcomes of remote asynchronous telerehabilitation are equivalent to traditional therapy following total knee arthroplasty: a randomized control study. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23:239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. IOM . The Learning Health Systems: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15. AHRQ . About Learning Health Systems. https://www.ahrq.gov/learning-health-systems/about.html. Accessed May 23, 2020.

- 16. Riley WT, Glasgow RE, Etheredge L, Abernethy AP. Rapid, responsive, relevant (R3) research: a call for a rapid learning health research enterprise. Clin Transl Med. 2013;2:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Health Systems Respond to COVID-19: Priorities for Rapid-Cycle Evaluations. AcademyHealth website. https://www.academyhealth.org/sites/default/files/healthsystemsrespondtocovid_april2020.pdf. 2020. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johnson K, Gustafson D, Ewigman B. Using Rapid-Cycle Research to Reach Goals: Awareness, Assessment, Adaptation, Acceleration. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stoto M, Oakes M, Stuart E, Brown R, Zurovac J, Priest EL. Analytical methods for a learning health system: 3. analysis of observational studies. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2017;5:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Seaman SR, White IR. Review of inverse probability weighting for dealing with missing data. Stat Methods Med Res. 2013;22:278–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greene SM, Reid RJ, Larson EB. Implementing the learning health system: from concept to action. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]