Abstract

Objectives

This study systematically reviewed existing qualitative evidence of family members’ experiences prior to the initiation of mental health services for a loved one experiencing their first episode of psychosis (FEP).

Methods

A meta-synthesis review of published peer-reviewed qualitative studies conducted between 2010 and 2019 were included. Keyword searches were performed in four electronic databases and the reference lists of primary manuscripts. Two independent reviewers used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist to assess methodological quality of each study.

Results

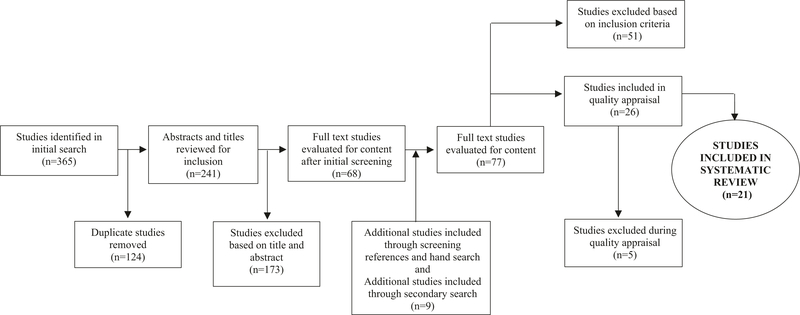

A total of 365 articles were initially identified and 9 were articles identified in a secondary review and literature search. A total of 21 met inclusion criteria. Of those included in this review 169, mothers were the primary family to recall experiences. The meta-synthesis identified four major themes related to family member experiences prior to the initiation of mental health services for FEP: the misinterpretation of signs, the emotional impact of FEP on family members, the effect of stigma on family members, and engaging with resources prior to mental health services for FEP.

Conclusions

Additional research is needed to develop healthy communication strategies that effectively deliver educational information about psychosis. This meta-synthesis also identified the need to understand help-seeking behaviors among families of those with FEP in effort to reduce the duration of untreated psychosis and improve pathways to care often initiated by a family member.

Keywords: Family members, Caregivers, Qualitative, Meta-synthesis, First episode psychosis

Each year an estimated 115,000 individuals experience their first episode of psychosis (FEP) (Kirkbride et al. 2012; Simon et al. 2017). Seventy percent of these cases occur before the age of 25 years (Kirkbride et al. 2006) and is a critical point for family members and their loved ones in the trajectory of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (Lincoln and McGorry 1995). Research suggests that the earlier mental health services are initiated the greater likelihood that these services are effective in improving psychiatric symptoms and quality of life (Azrin et al. 2015; Kane et al. 2015a; Mueser et al. 2015; Rosenheck et al. 2016).

There are various team-based treatment models tailored for individuals with FEP. Across Europe and Australia these models are referred to as early intervention programs (EIP) whereas in the US these programs are commonly referred to as coordinated specialty care (CSC) programs. EIPs (including CSC programs) utilize a team-based approach to deliver evidence-based treatments for individuals experiencing FEP and their family members. EIPs generally include at minimum, pharmacotherapy, individual or group therapy, vocational services (e.g., education and employment), and individual or group family education (Wright et al. 2019). An additional component may also include case management. Previous literature has demonstrated the effectiveness of such programs to positively impact the life trajectory of individuals experiencing early psychosis (Bird et al. 2010; Kane et al. 2015a); for instance, in the US, findings from a large randomized trial of an EIP significantly improved the clinical outcomes, functional outcomes, and quality of life of young people experiencing FEP (Kane et al. 2015a).

A large portion of youth and young adults enrolled in EIP programs for FEP report living with at least one family member (Onwumere et al. 2016). Family members who have loved ones experiencing FEP may encounter different issues from those who are caring for individuals further along in the trajectory of schizophrenia (Addington and Burnett 2004). Family members with loved ones experiencing FEP are typically less knowledgeable about symptoms, the ambiguity surrounding diagnosis, and encounters navigating the mental health system compared to family members with experience managing schizophrenia-spectrum diagnoses (Addington et al. 2005). Further, the experiences of family members are heightened during the FEP and much of the demand and burden are placed on family members or caregivers (Cook et al. 1994). Previous literature, primarily quantitative studies, has explored expressed emotion, family functioning, coping, burden, and distress (Koutra et al. 2016; McCann et al. 2012). EIP programs for FEP recognize the importance of family members or loved ones, thus, a large majority of these programs incorporate a family education and support (i.e., family psychoeducation) component.

Family members are typically the first to recognize changes in their loved ones’ behavior and have a key role in navigating pathways to care and the initiation of EIPs for FEP (Addington et al. 2005; Franz et al. 2010). However, it has been well documented that barriers to seeking help and obtaining appropriate care for individuals with FEP lengthens the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) (Commander et al. 1999; Compton et al. 2009, 2005; Lucksted et al. 2018; Morgan et al. 2006). Previous studies have demonstrated that DUP is associated with increased symptom severity, poorer functioning, as well as time to and level of remission of psychosis (Addington et al. 2015; Black et al. 2001; Harrigan et al. 2003; Loebel et al. 1992). A number of systematic reviews have heavily focused on quantitative findings related to DUP (Lloyd-Evans et al. 2011; Marshall et al. 2005; Norman et al. 2005), pathways to care (Anderson et al. 2010; Doyle et al. 2014; Singh and Grange 2006), and family members (Koutra et al. 2016). Given the importance of family members in seeking treatment for FEP, greater attention to how family members navigate through the mental health system and their experiences prior to the initiation of treatment is needed to improve the pathways to EIPs. This review aimed to examine qualitative findings that explore overall experiences of family members with FEP treatment. The primary aim of this systematic review was to assess family members perspective and opinions on the barriers and facilitators to FEP treatment.

Methods

Study Selection

Four electronic databases (PubMed, Google Scholar, MEDLINE, Web of Science) were searched for manuscripts published between January 2010 to August 2018. Subject keywords and phrases were limited to; first episode psychosis, early-onset schizophrenia, family member, caregiver, sibling, qualitative methods, interviews, focus groups, perspectives. The results were limited to only peer-reviewed articles published in English and qualitative studies involving human participants. To expand the inclusion of potential studies, a secondary search was conducted to identify manuscripts published from September 2018 to June 2019.

For initial screenings all articles were assessed based on titles and abstracts. Two reviewers screened all titles and abstracts for relevance, namely words indicating studies utilized qualitative methods (e.g., perceptions, opinions, experiences, qualitative, focus groups, interviews) from the family members’ perspectives. Based on the initial screening, the studies’ full text were then reviewed by one reviewer and examined for eligibility, with the second reviewer checking all included and excluded studies. A hand search of references and citations of primary articles was performed by two reviewers independently. Two reviewers met several times to discuss studies and came to a consensus of which studies were to be included.

Quality Assessment

Qualitative studies that met inclusion criteria were evaluated for methodological quality. To accomplish this, the 10-item Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist was utilized to assess all articles by two reviewers (CASP 2017). Authors independently appraised each study, differences were resolved by a third reviewer, and scores were averaged. Several studies have used the CASP qualitative checklist to conduct systematic reviews (Tindall et al. 2018b). Table 1 outlines the CASP scores for all the articles included in this review.

Table 1.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative appraisal

| CASP questions | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (year) | Was there a clear statement clear of aims? | Is qualitative method appropriate? | Was the research design appropriate? | Was the recruitment strategy appropriate? | Was data collected to address the issue? | Has the relationship between researcher and participants been considered? | Have ethical issues been considered? | Was data analysis rigorous? | Is there a clear statement of findings? | How valuable is the research? |

| 1. Allard et al. (2018) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| 2. Cadario et al. (2012) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| 3. Chen et al. (2016) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| 4. Connor et al. (2016) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| 5. dos Santos Martin et al. (2018) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| 6. Franz et al. (2010) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| 7. Giacon et al. (2019) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| 8. Hasan and Musleh (2017) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| 9. Hernandez et al (2019) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| 10. Ienciu et al. (2010) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 1 | Y |

| 11. Kumar et aL (2019) | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | Y |

| 12. Lavis et al. (2015) | 1 | 0 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 1 | Y |

| 13. Lucksted et al. (2018) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| 14. Marthoenis et al. (2016) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| 15. McCann et al. (2011) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| 16. Napa et al. (2017) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| 17. Petrakis et al. (2013) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| 18. Skubby et al. (2015) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | Y |

| 19. Tanskanen et al. (2011) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| 20. Tindall et al (2018a) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| 21. Yarborough et al. (2018) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

Screening, Data Extraction, and Synthesis

Initial screening of articles was conducted by the first author and a research assistant based on the information contained in their titles and abstracts. Full-text screening and using CASP for quality assessment were conducted by the authors. The authors discussed and resolved remaining disagreements about inclusion or exclusion of an article. The following data was extracted for each included study: article title, first author, published year, locations where the study was conducted, methods and procedures, themes, and outcomes (Table 2). Two authors reviewed all details extracted from the set of included studies for consistency; disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Table 2.

Summary of each article included in review

| Author (year) | Sample | Race/ethnicity | Location | Methods/procedures | Themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allard et al. (2018) |

N = 18 Caregivers Age range: 34–81 years Mage = 46 years |

– | Great Britain | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis Grounded theory/phenomenological analytical approach |

1. Retrospective accounts of desperation 2. Service engagement and relief 3. Hope and optimism |

| Cadario et al. (2012) | N = 12 Caregivers | 58% European 33% Māori 9% Māori /Cook Island Maori |

New Zealand | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis General inductive approach |

1. Difficulties noticed 2. Lack of awareness of mental illness; 3. How help was sought, and which service was approached 4. Thoughts about illness precipitants 5. Experience of services and suggestions; 6. Beliefs and knowledge of mental illness |

| Chen et al. (2016) |

N = 16 Parents Mage = 53.1 years |

69% White 19.8% Hispanic 6.3% African American 6.3% Asian |

United States | Semi-structured interviews Directed content analysis |

1. Contemplation stage: initial awareness, recognizing severity and considering options. 2. Action stage: help-seeking intention, securing help and service appraisal |

| Connor et al. (2016) | N = 14 Family members | – | Great Britain | Semi-structured interviews Deductive analysis |

1. Family response to illness: withdrawal, normalization, fear of stigma, fear of loss and guilt, lack of knowledge about services, triggers for help-seeking, GP contact |

| dos Santos Martin et al. (2018) |

N = 13 Family members Mage = 47.5 years |

– | Brazil | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

1. Lack of knowledge and difficulty in recognizing the mental illness 2. Not knowing where to seek specialized treatment 3. Stigma, prejudice and resistance to psychiatric treatment |

| Franz et al. (2010) |

N = 12 Family members Mage = 47.8 years |

100% African American | United States | Semi-structured interviews Grounded theory |

1. Society’s beliefs about mental illnesses 2. Families’ beliefs about mental illnesses 3. Fear of the label of a mental illness 4. Raised threshold for the initiation of treatment. |

| Giacon et al. (2019) |

N = 13 Family members Age Range: 37–75 years |

– | Brazil | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

1. Waiting move: trying to justify the behavior of the youth 2. Not understanding the psychosis 3. Seeking help |

| Hasan and Musleh (2017) |

N = 27 Family members Age range: 37–68 years Mage = 47 years |

– | Jordan | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

Lack of awareness about mental illness and associated symptoms Perceived stigma The role of the extended family Financial problems |

| Hernandez et al. (2019) |

N = 33 Caregivers Age range: 25–62 years Mage = 42 years |

100% Latino | United States | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

1. Relationships: engaged vs. disengaged, active vs. poor communication 2. Awareness: misattributions, lower threshold to behavioral change, patient treatment resistance, accommodation 3. Treatment seeking: family caregiver direct vs. indirect action, extended support network |

| Ienciu et al. (2010) | N = 25 Family members | – | Romania | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

1. Society’s beliefs about mental illness 2. Families’ beliefs about mental illness 3. Perceived stigma of a mental illness diagnosis 4. Misattribution of symptoms and denial 5. Raised threshold for initiation of treatment |

| Kumar et al. (2019) |

N = 30 Caregivers Mage = 37.7 years |

– | India | Focus groups Grounded theory |

1. Information regarding illness 2. Information regarding treatment 3. Availability and accessibility of treatment 4. Identification and recognition of mental health and physical problems in family members 5. Management of psychosocial issues related to patient’s illness 6. Optimum quality of care from treatment facility 7. Services provided by the government |

| Lavis et al. (2015) |

N = 80 Caregivers Age range: 23–80 years Mage = 49.9 years |

87.5% White British 2.5% White Irish 2.5% White Other 2.5% Asian Pakistani 1.25% Mixed White/ Asian 1.25% Asian Indian 2.5% Mixed Ethnicity |

Great Britain | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

1. Carers’ accounts of what they do: ‘producing normality’, vigilance, and medication management 2. Carers’ accounts of how they feel: reward, distress, and reconfigured lives 3. Talking and listening: services and carers |

| Lucksted et al. (2018) |

N = 18 Family members Age range: 25–65+ years |

44.5% African American 22% Asian, Pacific Islander 33% White, Caucasian 5.5% Other |

United States | Semi-structured interviews Inductive analysis Thematic analysis |

1. Direct family engagement: family distress and uncertainty about engagement, program outreach to family members, program characteristics, and program flexibility and individualization 2. Program effectiveness 3. Competing priorities and program logistics 4. Family member roles in client engagement: practical assistance, encouragement to engage, autonomy dynamics |

| Marthoenis et al. (2016) |

N = 16 Family members Age range: 27–68 years Mage = 47 years |

81% Acehnese 19% Gayonese |

Indonesia | Semi-structured interviews Qualitative content analysis Thematic analysis |

Misattribution of the cause and symptoms of mental disorders Perceived stigma Role of extended family Financial issues Distance to psychiatric hospital Perceived complicated bureaucratic system |

| McCann et al. (2011) |

N = 20 Caregivers Age range: 21–76 years Mage = 49 years |

– | Australia | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

1. GPs as a resourceful or an unresourceful means of access to FEP services 2. Encountering barriers accessing FEP services 3. Carers’ knowledge, experience and assertiveness enhancing access |

| Napa et al. (2017) |

N = 31 Family members Age range: 36–46+ years |

– | Thailand | Semi-structured interviews Grounded theory |

1. Communicating to gain support and understanding 2. Capturing solutions 3. Engaging in the family caregiving role |

| Petrakis et al. (2013) |

N = 12 Family members Age range: 21–70 years |

75% Australian 16.7% Asian 8.3% African |

Australia | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

1. Reduced isolation 2. Sense of collective experience 3. Opportunity to ventilate and feel heard 4. Reduced stigma and shame 5. Increased knowledge about mental health 6. Enhanced skills in supporting the person experiencing mental illness |

| Skubby et al. (2015) | N = 11 Parents | 64% White 36% African American |

United States | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

1. Delaying access to treatment 2. Facilitating access to treatment |

| Tanskanen et al. (2011) |

N = 9 Family members Age range: 26–68 years |

56% White British 22% White Other 11% Black Caribbean 11% Mixed race |

Great Britain | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

1. Understanding of symptoms and experiences 2. Help-seeking processes 3. Beliefs and knowledge about mental health services 4. Responses of social networks to illness onset and help-seeking |

| Tindall et al. (2018a) | N = 5 Family members | – | Australia | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

1. Emotional toll on caregivers 2. Experiences seeking support for their loved one |

| Yarborough et al. (2018) | N = 10 Family members | – | United States | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

1. Care seeking delays 2. Coping strategies 3. Caregivers often attribute symptoms to typical teenage behavior 4. Autonomy and privacy |

Results

Search Results

The initial literature search identified 365 studies of which 68 studies were include in the full-text evaluation; 297 were removed after a review of abstract and title, or duplication. Four additional studies were identified through the hand search of citations. A secondary literature search identified five additional studies that were included in the full-text evaluation. Independent review of the 77 studies revealed 26 studies that meet the inclusion criteria and were appraised (see Fig. 1). Five articles were removed after further discussion during the CASP appraisal process due to being outside the purview (e.g., focused on family coping strategies or evaluation of a family-oriented program) of this review. A final total of 21 studies were included in this review.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart on selection of studies included in review

Description and Demographics of Studies Included in Review

Of the 21 studies included in this review, the majority were conducted in the North America (n = 6; US) and Europe (n = 5; Great Britain, Romania), followed by four in Australia and New Zealand, three in Asia (Thailand, Indonesia, India), two in South America (Brazil), and one in the Middle East. Most studies included in this review were inperson interviews with the exception of one (Kumar et al. 2019) which used focus groups. Twenty were unique studies and included a total of 425 family members who contributed to findings presented in this meta-synthesis. Six studies did not distinguish between which parent (e.g., mother or father) participated in the study (Hasan and Musleh 2017; Hernandez et al. 2019; Marthoenis et al. 2016; McCann et al. 2011; Napa et al. 2017; Yarborough et al. 2018), of the 15 remaining studies, the majority of family members represented were mothers (n = 169), followed by 61 fathers (n = 61; See Table 2).

Emotional Impact

Thirteen of the 21 studies (62%) (Allard et al. 2018; Chen et al. 2016; Connor et al. 2016; Franz et al. 2010; Giacon et al. 2019; Kumar et al. 2019; Lavis et al. 2015; Lucksted et al. 2018; Napa et al. 2017; Petrakis et al. 2013; Tanskanen et al. 2011; Tindall et al. 2018a; Yarborough et al. 2018) discussed the psychological and mixed emotion impacts on family members of individuals with FEP prior to referral or treatment initiation. These studies specifically mentioned the development or feeling of desperation (Allard et al. 2018), distress (Lavis et al. 2015; Lucksted et al. 2018; Napa et al. 2017; Tindall et al. 2018a), fear (Connor et al. 2016), confusion (Kumar et al. 2019; Lavis et al. 2015; Tindall et al. 2018a), sadness (Cadario et al. 2012), guilt (Connor et al. 2016; Franz et al. 2010; Hasan and Musleh 2017; Tanskanen et al. 2011; Yarborough et al. 2018) loss (Lavis et al. 2015; Lucksted et al. 2018), general emotional wear and pain (Giacon et al. 2019) and isolation (Napa et al. 2017). These emotional responses penetrated their everyday caregiving role and were perceived as the most important factor that determined their capacity to support their loved one with FEP. The majority of family members went through these emotional reactions before accepting and realizing that formal help should be sought. The emotional impacts such as guilt resulted in feeling discouraged and isolated, which in turn deterred help-seeking behaviors and engagement in mental health services.

Although most families reported a decline in overall well-being, many families developed coping strategies (Chen et al. 2016; Connor et al. 2016; Franz et al. 2010; Giacon et al. 2019; Hernandez et al. 2019; Ienciu et al. 2010; Lavis et al. 2015). Family members revealed the process of adopting coping strategies as a positive adjustment to caring for a loved one with FEP. Through this process family members reflected that family support groups and shared experience fostered empowerment and reduced the feeling of isolation (Allard et al. 2018; Lucksted et al. 2018; Petrakis et al. 2013; Skubby et al. 2015).

Misinterpretation of Signs

Fourteen of the 21 (67%) studies revealed that family members often misattributed the signs and non-specific nature of early symptoms that contributed to the delay in seeking treatment for their loved one (Allard et al. 2018; Cadario et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2016; Connor et al. 2016; dos Santos Martin et al. 2018; Franz et al. 2010; Giacon et al. 2019; Hasan and Musleh 2017; Hernandez et al. 2019; Marthoenis et al. 2016; Napa et al. 2017; Skubby et al. 2015; Tanskanen et al. 2011; Yarborough et al. 2018). Family members were also uncertain as to whether the ‘difficulties’ that their loved one was experiencing were even related to illness. The most common signs observed by family members during the early stage of psychosis included somatic symptoms, especially loss of appetite, weight loss, sleep disturbance (Cadario et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2016; dos Santos Martin et al. 2018; Giacon et al. 2019; Tanskanen et al. 2011), panic attacks (Chen et al. 2016), hallucinations (Chen et al. 2016; Giacon et al. 2019), and social and emotional withdrawal (Connor et al. 2016; dos Santos Martin et al. 2018; Giacon et al. 2019; Yarborough et al. 2018). Prior to treatment family members tended to normalize these signs and construct alternative explanations to explain behaviors. The most commonly used alternative explanations were substance use (Chen et al. 2016; dos Santos Martin et al. 2018; Giacon et al. 2019; Hernandez et al. 2019; Napa et al. 2017; Skubby et al. 2015), rebellious teenager behavior (Chen et al. 2016; dos Santos Martin et al. 2018; Giacon et al. 2019), life stressors (dos Santos Martin et al. 2018; Hernandez et al. 2019; Skubby et al. 2015), or supernatural causes (Connor et al. 2016; dos Santos Martin et al. 2018; Hasan and Musleh 2017; Marthoenis et al. 2016; Napa et al. 2017). Of the five studies that referenced supernatural origins for psychosis, the majority of individuals that referenced ‘evil spirits’ or ‘possession’ were Asian (Connor et al. 2016; Marthoenis et al. 2016; Napa et al. 2017).

The emergence and escalation of psychotic symptoms and/or socially disruptive behaviors (Chen et al. 2016; Marthoenis et al. 2016) or violent or suicidal behaviors (Connor et al. 2016; Giacon et al. 2019; Ienciu et al. 2010; Tanskanen et al. 2011) often served as the catalyst for family members deciding to seek help. On the other hand, some vicarious experience could also be the catalyst of seeking help earlier, for example, family history of psychopathology allows family members to recognize early signs of psychosis (Chen et al. 2016; Napa et al. 2017).

Stigma

Of the 21 studies included in this meta-synthesis, family members from seven studies (33%) expressed the impact of stigma towards mental health, and more specifically psychosis, was a contributing factor in the delay to seek mental health services (Chen et al. 2016; dos Santos Martin et al. 2018; Franz et al. 2010; Hasan and Musleh 2017; Ienciu et al. 2010; Marthoenis et al. 2016; Tanskanen et al. 2011). Family members expressed concerns related to being labeled for receiving mental health services and feeling isolated from relatives, friends, and acquaintances (i.e., neighbors) (dos Santos Martin et al. 2018; Hasan and Musleh 2017; Marthoenis et al. 2016), in the early phases of psychosis. Family members also reflected that more public health campaigns should focus on increasing awareness about mental illness within families, the community, and in society as a whole (Cadario et al. 2012; Franz et al. 2010; Ienciu et al. 2010).

Accessing Specialty Services

Fifteen studies (71%) identified three major social and professional resources for family members in the process of identifying the appropriate services for FEP (Allard et al. 2018; Cadario et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2016; Connor et al. 2016; dos Santos Martin et al. 2018; Franz et al. 2010; Giacon et al. 2019; Hasan and Musleh 2017; Hernandez et al. 2019; Kumar et al. 2019; Marthoenis et al. 2016; McCann et al. 2011; Napa et al. 2017; Petrakis et al. 2013; Skubby et al. 2015; Tanskanen et al. 2011). These resources included medical personnel (e.g., psychiatrists, mental health therapists, primary health care providers), school staff (e.g., school counselor, teachers), and social networks (e.g., relatives, friends, religious leaders). Seven studies conducted in six different counties (i.e., New Zealand, US, Great Britain, Jordan, Indonesia, Brazil), identified that several family members sought initial help from faith healers or religious leaders (Cadario et al. 2012; Connor et al. 2016; dos Santos Martin et al. 2018; Franz et al. 2010; Hasan and Musleh 2017; Marthoenis et al. 2016; Skubby et al. 2015). Among medical personnel, family members sought resources from primary health care providers and psychiatrists were generally utilized as a last resort (Cadario et al. 2012), although reasons for this were not revealed. Interactions with medical personnel and school staff resulted in the immediate referrals to specialty services (Cadario et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2016). However, family members from four studies expressed that referrals and suggestions from religious leaders (Cadario et al. 2012; Kumar et al. 2019), medical personnel (Giacon et al. 2019; Kumar et al. 2019), and school staff were unhelpful (Skubby et al. 2015), which often resulted in the further delay of treatment. Experiences of being referred to unsuitable mental health services, misattributing symptoms of psychosis, and misdiagnosis were several of the reasons why family members thought these referrals were unhelpful. Five studies highlighted the perceived inability for family members to locate resources or useful information due to the lack of direction or language barriers (Connor et al. 2016; Hernandez et al. 2019; McCann et al. 2011; Skubby et al. 2015; Tanskanen et al. 2011). Previous experiences with relatives, friends, and social media that were negative induced fear of accessing specialty services for FEP among family members (Cadario et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2016).

The time dedicated to acquiring referrals to specialty services and locating information resources are often combined with practical and systematic barriers to accessing mental health services revealed in six studies included in this meta-synthesis (Chen et al. 2016; Connor et al. 2016; Franz et al. 2010; Hasan and Musleh 2017; Ienciu et al. 2010; Marthoenis et al. 2016). Family members identified several practical barriers such as lack of transportation, insurance coverage, cost of services, and travel distance to specialty services as practical barriers. Systematic barriers included, limited appointment times, unclear criteria for enrollment, and competence of the mental health professionals (e.g., misattribution of symptoms, misdiagnosis).

Discussion

The present meta-synthesis systematically examined the qualitative literature pertaining to family experiences prior to seeking treatment for a loved one with FEP. Due to the young age at which an individual typically develops psychosis (Kirkbride et al. 2006) and the limited insight into diagnosis (Lal and Malla 2015; Marthoenis et al. 2016), the burden of help-seeking in the early stages of psychosis is usually initiated by family members. Findings from the meta-synthesis of 21 qualitative studies identified four distinct themes: the misattribution of signs and symptoms, the emotional impact on family members, stigma associated with psychosis, and accessing specialty services. These four themes expressed by family members provided insight into the common experiences navigating the presentation of FEP and the impact on family members, as well as the process to accessing mental health services for FEP. Given that the delay in treatment results in longer DUP, which is associated with worse outcomes for individuals with FEP (Lloyd-Evans et al. 2011; Marshall et al. 2005; Norman et al. 2005), it is essential to understand the experiences of family members to identify points in the pathway of care that can be targeted for further improvement.

In the early phases of psychosis, studies revealed that family members misattributed the signs and symptoms of psychosis (Cadario et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2016; Connor et al. 2016; dos Santos Martin et al. 2018; Giacon et al. 2019; Hasan and Musleh 2017; Hernandez et al. 2019; Marthoenis et al. 2016; Napa et al. 2017; Skubby et al. 2015; Tanskanen et al. 2011; Yarborough et al. 2018) specifically negative symptoms (e.g., withdrawal, isolation, disinterest, lack of motivation) (Cadario et al. 2012; Connor et al. 2016; dos Santos Martin et al. 2018; Giacon et al. 2019; Hasan and Musleh 2017; Marthoenis et al. 2016; Yarborough et al. 2018). Individuals that present solely with negative symptoms (e.g., social isolation or apathy) tend to have a significantly longer DUP than individuals that present with only positive (e.g., hallucinations or delusions) or both positive and negative symptoms (Platz et al. 2006). Families would attribute changes in behaviors to various explanations including substance use, typical adolescent behavior, or superstitious experiences (e.g., possession, demons, black magic, ghosts, sorcery) (Cadario et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2016; dos Santos Martin et al. 2018; Hasan and Musleh 2017; Hernandez et al. 2019; Marthoenis et al. 2016; Napa et al. 2017; Skubby et al. 2015; Yarborough et al. 2018). Several family members that endorsed misattributing psychotic symptoms for spiritual reasons were Asian, Middle Eastern, or South American. Whereas family members that sought out religious leaders or faith healers occurred across all racial and ethnics groups. Overall, misattribution of symptoms may be explained by the lack of knowledge about psychosis and its presentation among family members, medical personnel, and school staff. Family members suggested that public health campaigns to raise the level of awareness about early symptoms would be beneficial and reduce stigma associated with psychosis (Cadario et al. 2012; Franz et al. 2010; Ienciu et al. 2010), such campaigns have been associated with a shortened DUP (Joa et al. 2007).

Consistent with previous literature, among caregivers in other populations, family members suffer from a range of significant physical, psychological, and emotional problems (Onwumere et al. 2016). As an example, family caregivers experienced sleep deficiencies (Smith et al. 2018), elevated levels of anxiety or depression (Tennakoon et al. 2000), high blood pressure (Poon et al. 2018), increased health utilization and more frequent visits to their general practitioner (Tennakoon et al. 2000), and overall reduction in well-being (McCann and Lubman 2014). The presence of psychological and physical symptoms, combined with the stress and burden of caring for and managing a loved ones’ illness, may further impact the quality of life of family members (Onwumere et al. 2016). These findings highlight the need for additional research focused on identifying and developing strategies to mitigate symptoms at specific points along the pathway to treatment. This underscores the importance of evidence-based interventions such as family psychoeducation and possible adaptations to address constructs beyond expressed emotion.

Once a crisis occurred with an individual experiencing FEP, family members sought three main sources for help: medical professionals, professional advocates, and their support system (e.g., friends and family) (Cadario et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2016; dos Santos Martin et al. 2018; Giacon et al. 2019; Kumar et al. 2019; Marthoenis et al. 2016; McCann et al. 2011; Napa et al. 2017; Petrakis et al. 2013; Skubby et al. 2015; Tanskanen et al. 2011). The differences in outreach activities for EIP models may be associated with family member experiences and the availability of such services may contribute to difficulties experienced by medical personnel and school staff in referring individuals with FEP and their family members to specialty services for FEP. Medical personnel, particularly general practitioners, and professional advocates should be educated on the early signs of psychosis and screening tools for at risk individuals such as the Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences—Positive 15-items (CAPE-P15), as they are typically the first source in referring family members to the correct services. Two studies conducted in Norway targeted information campaigns, one for medical personnel and the other for school staff. It was found that early detection programs for medical personnel and information campaigns for teachers aided in shorten DUP and assisted in the individuals in correctly identifying psychosis (Langeveld et al. 2011; Melle et al. 2004).

Several logistical and systematic barriers (e.g., referral, availability of services) were consistent among the studies included in this review, in light of geographical locations of studies. However, family member experiences may be unique to specific countries as a result of different health care systems and availability of EIPs or other specialty services. For instance, family members from studies conducted in the US and Jordan stated that the cost of treatment and insurance coverage as contributing factors to delays or complication in the initiation of treatment, which were not mentioned by family members in Australia or Great Britain. It is also important to consider the status of EIPs and mental health reform and the impact of family member experiences and encounters with their respective mental health or primary care systems. Australian EIPs paved the way for early psychosis programs starting in 2003 and have a nationwide program with set guidelines for early detection, acute care, and continuing care (McGorry 2015). Within the US, although programs may vary between states, EIPs have increased by approximately 2150% from 12 in 2008 to approximately 270 programs in 2018 (National Association of State and Mental Health Program Directors 2016; National Association of State and Mental Health Program Directors 2018), following the initial findings from the Recovery After An Initial Schizophrenia Episode—Early Treatment Program (Kane et al. 2015a, b). The current landscape of EIPs and the initiatives to improve services for those atrisk or diagnosed with a psychotic disorder, hopes to improve the dissemination of mental health education (e.g., symptoms, screenings), streamline referrals, and increase access to EIPs through expansion.

Limitations

The authors determined that several articles had a moderate methodological approach but were still included in the review. Although this may have been a limitation, the authors chose not to exclude these studies in order to add more depth to the review and to capture the perspectives of family members from a variety of countries. When interrupting the results presented in this review, variations in health care systems across countries can have a direct impact on accessing specialty services. Furthermore, differences in outreach activities for EIP and CSC models may be associated with family member experiences and the availability of such services may contribute to difficulties experienced by medical personnel and school staff in referring individuals with FEP and their family members to specialty services for FEP. It is important to note that most of these studies were conducted in developed, English-speaking countries, which may reduce the generalizability of the perspectives from the family members and constraints on identifying specific cultural experiences. Additionally, the years for this literature review were restricted from 2010 to 2019. This restriction allows for more focus on the current research from the past decade but does remove a few relevant studies that were published more than ten years ago. Another possible limitation is the analysis to determine themes in each paper (e.g., thematic analysis vs. grounded theory). Although the methodological approaches varied across studies, prominent themes were relatively consistent across studies, enhancing the findings outlined in this meta-synthesis. The majority of the interviews were retrospective, which could result in inaccuracies and imperfect memories surrounding the time of the first-episode psychosis. Further limitations include the way in which the family members were recruited for the studies. The family members that participated in these studies may have more engagement with services as they were recruited through EIPs, which could skew the findings or overlook experiences from non-engaged family members.

Family members are typically at the forefront for initiating treatment for their loved one, this meta-synthesis highlights the experiences of family members from the emergence of a loved ones’ symptoms to steps taken to initiate treatment. Understanding where the points of intervention for support and areas to improve in the identification of FEP is imperative to improving the pathway to EIPs or other specialty services. Many of the barriers could be confronted with early detection programs and information campaigns. With increased awareness within the general population, or targeted at where help-seeking is initial sought (e.g., general practitioners, teachers, school counselors), the prime barriers including misattributing symptoms, emotional impact on family members, coping strategies (e.g., normalizing), stigma of psychosis, and access to specialty services would diminish resulting in shortened DUP. Future studies should not only focus on service users’ help-seeking and engagement but family members’ as well. Although further qualitative-driven studies are needed, this literature review identifies family members play a vital role in the care of those experiencing FEP. An understanding that family member needs may be different from consumer needs is important in the development and improvement of mental health campaigns and services.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Behavioral Health Innovations’ undergraduate research assistants J.W. and A.D. in helping with literature searches and creating tables for this manuscript.

Funding This study was supported by K01MH117457 from the National Institute of Mental Health, R25DA035163 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and R01AA020248 and R01AA020248-05S1 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical Approval This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Addington J, & Burnett P (2004). Working with families in the early stages of psychosis In Psychological interventions in early psychosis. A treatment handbook (pp. 99–116). West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Collins A, McCleery A, & Addington D (2005). The role of family work in early psychosis. Schizophrenia Research, 79(1), 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Heinssen RK, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, Marcy P, Brunette MF,… Penn D (2015). Duration of untreated psychosis in community treatment settings in the United States. Psychiatric Services, 66(7), 753–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard J, Lancaster S, Clayton S, Amos T, & Birchwood M (2018). Carers’ and service users’ experiences of early intervention in psychosis services: implications for care partnerships. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12(3), 410–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K, Fuhrer R, & Malla A (2010). The pathways to mental health care of first-episode psychosis patients: a systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 40(10), 1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin ST, Goldstein AB, & Heinssen RK (2015). Early intervention for psychosis: the recovery after an initial schizophrenia episode project. Psychiatric Annals, 45(11), 548–553. [Google Scholar]

- Bird V, Premkumar P, Kendall T, Whittington C, Mitchell J, & Kuipers E (2010). Early intervention services, cognitive–behavioural therapy and family intervention in early psychosis: systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(5), 350–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black K, Peters L, Rui Q, Milliken H, Whitehorn D, & Kopala L (2001). Duration of untreated psychosis predicts treatment outcome in an early psychosis program. Schizophrenia Research, 47(2), 215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadario E, Stanton J, Nicholls P, Crengle S, Wouldes T, Gillard M, & Merry SN (2012). A qualitative investigation of first-episode psychosis in adolescents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(1), 81–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASP U (2017). Critical appraisal skills programme (CASP). Qualitative Research Checklist, 31(13), 449. [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Gearing RE, DeVylder JE, & Oh HY (2016). Pathway model of parental help seeking for adolescents experiencing first‐episode psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 10(2), 122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commander M, Cochrane R, Sashidharan S, Akilu F, & Wildsmith E (1999). Mental health care for asian, black and white patients with non-affective psychoses: pathways to the psychiatric hospital, in-patient and after-care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 34(9), 484–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton MT (2005). Barriers to initial outpatient treatment engagement following first hospitalization for a first episode of nonaffective psychosis: a descriptive case series. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 11(1), 62–69. 00131746–200501000-00010 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton MT, Goulding SM, Gordon TL, Weiss PS, & Kaslow NJ (2009). Family-level predictors and correlates of the duration of untreated psychosis in african american first-episode patients. Schizophrenia Research, 115(2), 338–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor C, Greenfield S, Lester H, Channa S, Palmer C, Barker C,… Birchwood M (2016). Seeking help for first‐episode psychosis: a family narrative. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 10(4), 334–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JA, Lefley HP, Pickett SA, & Cohler BJ (1994). Age and family burden among parents of offspring with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 64(3), 435–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos Martin I, Giacon BCC, Vedana KGG, Zanetti ACG, Fendrich L, & Galera SAF (2018). Where to seek help? Barriers to beginning treatment during the first-episode psychosis. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 5(3), 249–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle R, Turner N, Fanning F, Brennan D, Renwick L, Lawlor E, & Clarke M (2014). First-episode psychosis and disengagement from treatment: a systematic review. Psychiatric Services, 65(5), 603–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz L, Carter T, Leiner AS, Bergner E, Thompson NJ, & Compton MT (2010). Stigma and treatment delay in first‐episode psychosis: a grounded theory study. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 4(1), 47–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacon BCC, Vedana KGG, dos Santos Martin I, Zanetti ACG, Fendrich L, Cardoso L, & Galera SAF (2019). Family experiences in the identification of the first-episode psychosis in young patients. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 33(4), 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan SM, McGorry P, & Krstev H (2003). Does treatment delay in first-episode psychosis really matter? Psychological Medicine, 33(1), 97–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan AA, & Musleh M (2017). Barriers to seeking early psychiatric treatment amongst first-episode psychosis patients: a qualitative study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(8), 669–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez M, Hernandez MY, Lopez D, Barrio C, Gamez D, & López SR (2019). Family processes and duration of untreated psychosis among US latinos. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 13(6), 1389–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ienciu M, Romoşan F, Bredicean C, & Romoşan R (2010). First episode psychosis and treatment delay—causes and consequences. Psychiatria Danubina, 22(4), 540–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joa I, Johannessen JO, Auestad B, Friis S, McGlashan T, Melle I,… Larsen TK (2007). The key to reducing duration of untreated first psychosis: information campaigns. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 34(3), 466–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, Mueser KT, Penn DL, Rosenheck RA,… Estroff SE (2015a). Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(4), 362–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, Correll CU, Brunette MF, Mueser KT,… Robinson J (2015b). The RAISE early treatment program for first-episode psychosis: background, rationale, and study design. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(3), 240–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkbride JB, Errazuriz A, Croudace TJ, Morgan C, Jackson D, Boydell J… Jones PB (2012). Incidence of schizophrenia and other psychoses in england, 1950–2009: a systematic review and meta-analyses. PloS ONE, 7(3), e31660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkbride JB, Fearon P, Morgan C, Dazzan P, Morgan K, Tarrant J… Leff JP (2006). Heterogeneity in incidence rates of schizophrenia and other psychotic syndromes: findings from the 3-center AeSOP study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(3), 250–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutra K, Triliva S, Roumeliotaki T, Basta M, Lionis C, & Vgontzas AN (2016). Family functioning in first-episode and chronic psychosis: the role of patient’s symptom severity and psychosocial functioning. Community Mental Health Journal, 52 (6), 710–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar G, Sood M, Verma R, Mahapatra A, & Chadda RK (2019). Family caregivers’ needs of young patients with first episode psychosis: a qualitative study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 10.1177/0020764019852650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal S, & Malla A (2015). Service engagement in first-episode psychosis: current issues and future directions. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 60(8), 341–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langeveld J, Joa I, Larsen TK, Rennan JA, Cosmovici E, & Johannessen JO (2011). Teachers’ awareness for psychotic symptoms in secondary school: the effects of an early detection programme and information campaign. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 5(2), 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis A, Lester H, Everard L, Freemantle N, Amos T, Fowler D… Sharma V (2015). Layers of listening: qualitative analysis of the impact of early intervention services for first-episode psychosis on carers’ experiences. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 207(2), 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln CV, & McGorry P (1995). Who cares? Pathways to psychiatric care for young people experiencing a first episode of psychosis. Psychiatric Services, 46(11), 1166–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Evans B, Crosby M, Stockton S, Pilling S, Hobbs L, Hinton M, & Johnson S (2011). Initiatives to shorten duration of untreated psychosis: systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 198(4), 256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loebel AD, Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, Mayerhoff DI, Geisler SH, & Szymanski SR (1992). Duration of psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 149(9), 1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucksted A, Stevenson J, Nossel I, Drapalski A, Piscitelli S, & Dixon LB (2018). Family member engagement with early psychosis specialty care. Early intervention in psychiatry, 12(5), 922–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, Drake R, Jones P, & Croudace T (2005). Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(9), 975–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marthoenis M, Aichberger MC, & Schouler-Ocak M (2016). Patterns and determinants of treatment seeking among previously untreated psychotic patients in Aceh province, Indonesia: a qualitative study. Scientifica, 2016, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann TV, Lubman DI, & Clark E (2011). First‐time primary caregivers’ experience accessing first‐episode psychosis services. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 5(2), 156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann TV, Lubman DI, Cotton SM, Murphy B, Crisp K, Catania L,… Gleeson JF (2012). A randomized controlled trial of bibliotherapy for carers of young people with first-episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 39(6), 1307–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann TV, & Lubman DI (2014). Qualitative process evaluation of a problem-solving guided self-help manual for family carers of young people with first-episode psychosis. BMC psychiatry, 14(1), 168–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD (2015). Early intervention in psychosis: obvious, effective, overdue. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 203(5), 310–318. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melle I, Larsen TK, Haahr U, Friis S, Johannessen JO, Opjordsmoen S,… McGlashan T (2004). Reducing the duration of untreated first-episode psychosis: effects on clinical presentation. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(2), 143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan C, Abdul-Al R, Lappin JM, Jones P, Fearon P, & Leese M,… AESOP Study Group. (2006). Clinical and social determinants of duration of untreated psychosis in the AESOP first-episode psychosis study. The British Journal of Psychiatry The Journal of Mental Science, 189, 446–452. 189/5/446 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Penn DL, Addington J, Brunette MF, Gingerich S, Glynn SM,… McGurk SR (2015). The NAVIGATE program for first-episode psychosis: rationale, overview, and description of psychosocial components. Psychiatric Services, 66 (7), 680–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napa W, Tungpunkom P, Sethabouppha H, Klunklin A & Fernandez R (2017). A Grounded Theory Study of Thai Family Caregiving Process for Relatives with First Episode Psychosis. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research, 21(2), 158–170. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of State and Mental Health Program Directors. (2016). Fiscal years 2016 and 2017: snapshot of state plans for using the Community Mental Health Block Grant (MHBG) ten percent set-aside for early intervention programs. https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Information_Guide-Snapshot_of_State_Plans_Revision.pdf.

- National Association of State and Mental Health Program Directors. (2018). Fiscal year 2018: snapshot of state plans: for using the community mental health block grant 10 percent set-aside to address first episode psychosis. https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Snapshot_of_State_Plans.pdf.

- Norman RM, Lewis SW, & Marshall M (2005). Duration of untreated psychosis and its relationship to clinical outcome. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 187(S48), s19–s23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onwumere J, Shiers D, & Chew-Graham C (2016). Understanding the needs of carers of people with psychosis in primary care. The British Journal of General Practice The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 66(649), 400–401. 10.3399/bjgp16X686209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrakis M, Oxley J, & Bloom H (2013). Carer psychoeducation in first-episode psychosis: evaluation outcomes from a structured group programme. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 59 (4), 391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platz C, Umbricht DS, Cattapan-Ludewig K, Dvorsky D, Arbach D, Brenner H, & Simon AE (2006). Help-seeking pathways in early psychosis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(12), 967–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon AWC, Curtis J, Ward P, Loneragan C, & Lappin J (2018). Physical and psychological health of carers of young people with first episode psychosis. Australasian Psychiatry, 26 (2), 184–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Sint K, Lin H, Robinson DG, Schooler NR,… Brunette MF (2016). Cost-effectiveness of comprehensive, integrated care for first episode psychosis in the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 42(4), 896–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Coleman KJ, Yarborough BJH, Operskalski B, Stewart C, Hunkeler EM,… Beck A (2017). First presentation with psychotic symptoms in a population-based sample. Psychiatric Services. 10.1176/appi.ps.201600257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SP, & Grange T (2006). Measuring pathways to care in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review. Schizophrenia Research, 81(1), 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skubby D, Bonfine N, Tracy H, Knepp K, & Munetz MR (2015). The help-seeking experiences of parents of children with a first-episode of psychosis. Community Mental Health Journal, 51(8), 888–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LM, Onwumere J, Craig T, & Kuipers E (2018). Caregiver correlates of patient-initiated violence in early psychosis. Psychiatry research, 270, 412–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanskanen S, Morant N, Hinton M, Lloyd-Evans B, Crosby M, Killaspy H,… Johnson S (2011). Service user and carer experiences of seeking help for a first episode of psychosis: a UK qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 11(1), 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennakoon L, Fannon D, Doku V, O’Ceallaigh S, Soni W, Santamaria M,... Sharma T (2000). Experience of caregiving: relatives of people experiencing a first episode of psychosis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 177(6), 529–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tindall RM, Allott K, Simmons M, Roberts W, & Hamilton BE (2018a). Engagement at entry to an early intervention service for first episode psychosis: an exploratory study of young people and caregivers. Psychosis, 10(3), 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Tindall RM, Simmons MB, Allott K, & Hamilton BE (2018b). Essential ingredients of engagement when working alongside people after their first episode of psychosis: a qualitative meta‐synthesis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12(5), 784–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright A, Browne J, Mueser KT, & Cather C (2019). Evidence-based psychosocial treatment for individuals with early psychosis. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 29(1), 211–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarborough BJ, Yarborough MT, & Cavese JC (2018). Factors that hindered care seeking among people with a first diagnosis of psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 13(5), 1220–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]