Abstract

Understanding a tumor’s detailed molecular profile has become increasingly necessary to deliver the standard of care for patients with advanced cancer. Innovations in both tumor genomic sequencing technology and the development of drugs that target molecular alterations have fueled recent gains in genome-driven oncology care. “Basket studies,” or histology-agnostic clinical trials in genomically selected patients, represent one important research tool to continue making progress in this field. We review key aspects of genome-driven oncology care, including the purpose and utility of basket studies, biostatistical considerations in trial design, genomic knowledgebase development, and patient matching and enrollment models, which are critical for translating our genomic knowledge into clinically meaningful outcomes.

Keywords: genome-driven oncology, precision medicine, basket study, basket trial, knowledgebase

INTRODUCTION: THE LANDSCAPE OF GENOME-DRIVEN ONCOLOGY

The current oncology landscape is shaped by efforts to understand the molecular changes underlying cancer and attempts to target these molecular changes. The ability to rapidly and comprehensively detect such changes has improved dramatically in recent years. Advancements in sequencing technologies, such as high-throughput next-generation sequencing, have enabled the rapid identification of all classes of genomic alterations in tumors, including copy-number alterations, sequence mutations, and structural rearrangements in thousands of genes simultaneously (1).

The initial proof-of-concept of genome-driven oncology was the development of imatinib for treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemias (CML) harboring the BCR–ABL translocation (2). This led to remarkable gains in survival, and today patients with CML have life expectancies approaching that of the general population (3). Similarly, agents targeting human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-expressing breast cancer, BRAF V600-mutant melanoma, and EGFR-, ALK-, and ROS1-mutant lung cancer have dramatically improved outcomes (4–6). Understanding molecular changes in tumors can also help to select against ineffective therapies. For example, mutations in BRAF, KRAS, and NRAS predict for resistance to anti-EGFR therapies in colorectal cancers (7).

These early successes in targeting cancer’s genomic aberrations have propelled a paradigm of choosing therapy guided by an individual tumor’s molecular profile (8). Molecular characterization has become standard of care for many tumor types, including non-small cell lung cancer, breast cancer, melanoma, ovarian cancer, and some leukemias. Even this disease-specific paradigm of genomic profiling has been challenged by the recent accelerated approval of pembrolizumab for any tumor harboring microsatellite instability, raising the prospect that delivering the standard of care for all cancer patients will soon require some form of comprehensive genomic characterization (9).

As genomic characterization of tumors has moved from testing individual mutations to more comprehensive profiling of hundreds or even thousands of genes, the selection of treatment based on specific molecular biomarkers has grown both more ambitious and more complex. Early efforts followed traditional disease-specific clinical trial methodology, focusing on allocating patients with a specific tumor type to one of several therapies based, at least in part, on the molecular alteration identified in each patient. For example, the BATTLE trial adaptively randomized patients to one of four targeted treatment groups according to molecular alteration as defined via central genomic profiling (10, 11). The BATTLE study served as an early framework for novel adaptive clinical trial design and disease-specific molecular allocation of treatment. As our understanding of the genomic changes within specific tumor types has grown, so has the recognition that potentially actionable genomic alterations recur across a wide variety of tumor types, albeit often at low frequencies in any individual tumor type (12, 13). How then can the utility of precision oncology in targeting previously validated as well as entirely novel genomic biomarkers be expanded to a larger set of tumor types? Moreover, how can these potential benefits be efficiently and rigorously interrogated?

BASKET STUDIES: AN EMERGING APPROACH TO EVALUATING THE BENEFITS OF GENOME-DRIVEN ONCOLOGY

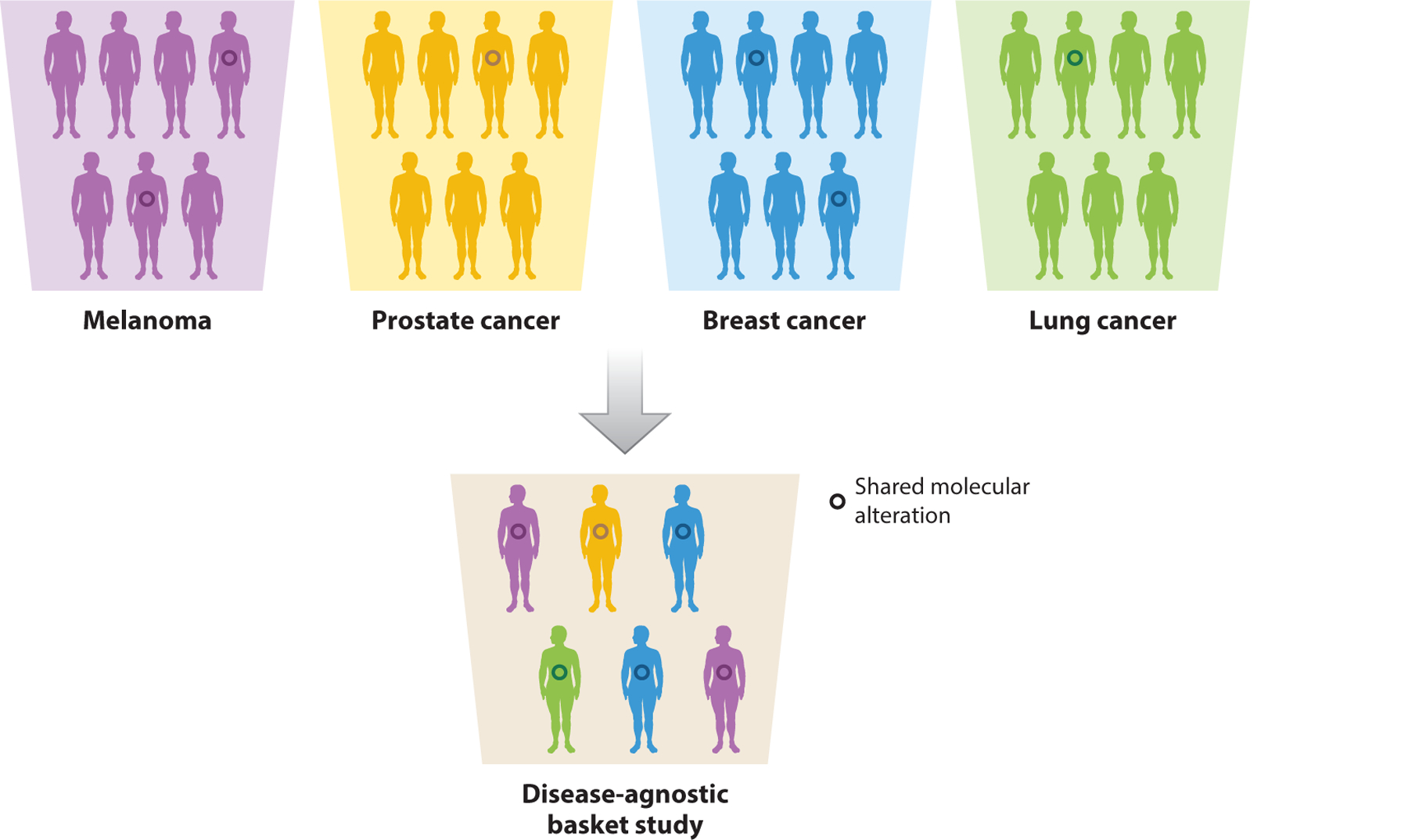

One key advance toward addressing these questions came through the development of “basket” studies, a new clinical trial paradigm that defines eligibility based on the presence of a specific genomic alteration, irrespective of histology. Unlike most clinical trials, which test a drug against a specific cancer type, the central organizing principle of a basket trial is the molecular alteration. The term basket arises from each collection of patients that harbors a particular mutation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

In contrast to a traditional, organ-site-specific trial, the central organizing principle of a basket study is the genomic alteration. A basket trial tests a particular therapy among patients with the same genomic alteration (depicted by the colored circles) across multiple cancer types.

We critically review some of the primary purposes of basket studies: (a) to provide initial proof-of-principle evidence for the clinical validation of a novel genomic target, (b) to clarify whether new drugs effectively inhibit their intended targets by evaluating them in optimal genomic candidates, (c) to screen for potential efficacy across multiple tumor types in order to guide more traditional, disease-specific follow-up studies, and (d) to generate pivotal data that support new standards of care. We use examples of different drug targets to illustrate several of these scenarios. We also consider how the optimal use of basket studies may differ for drugs that are investigational compared to those that have already been approved for another indication.

LESSONS LEARNED FROM BASKET STUDIES

One of the initial uses of a basket study was to determine whether a drug already approved to target a genomic alteration in one cancer type could be efficacious against the identical mutation in other cancer types. Given the growing number of agents approved to target genomic alterations in a tumor-specific context, and the observation that these alterations are rarely restricted to these tumor types, the potential for broadening the utility of genome-driven oncology through this approach could be vast. For example, BRAF V600 mutations occur in about half of all cutaneous melanomas. Among patients with V600-mutant melanoma, the use of RAF and MEK inhibitors has improved survival (14, 15). However, most RAF mutations occur in nonmelanoma cancers, raising the question of whether targeting BRAF in other cancers would lead to similar benefits. Disease-specific trials could be conducted in tumor types with a relatively high prevalence of BRAF mutations, including thyroid cancer, hairy cell leukemia, and non-small cell lung cancer (16–18). In contrast, the basket trial paradigm is particularly well suited to study tumor types that consistently but rarely harbor BRAF V600 mutations. As such, one of the first basket trials investigated the efficacy of BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib in patients harboring BRAF mutations across a variety of cancer types (19). Among other important observations, this study identified efficacy in two closely related rare disorders, Langerhans cell histiocytosis and Erdheim-Chester disease, for which there were no approved therapies (20). The results of this trial are expected to lead to US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of vemurafenib in several additional tumor types, providing proof-of-concept that this approach can advance the standard of care.

The basket trial design is also an efficient strategy to interrogate potentially actionable germline alterations, which can be seen at low frequencies in patients with a variety of tumor types. In a pivotal study testing olaparib that ultimately led to the first regulatory approval of a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, patients with germline BRCA1/2 mutations were treated across a spectrum of advanced cancers (21). The trial not only demonstrated initial proof-of-concept efficacy of PARP inhibition in BRCA1/2 germline-mutant prostate and pancreas cancer but also led directly to the FDA approval of olaparib in patients with ovarian cancer who harbor germline BRCA1/2 mutations, helping to establish a new standard of care for these patients. This study also led to large randomized phase III studies of PARP inhibitors in BRCA1/2 germline mutant breast and ovarian cancer, which have subsequently demonstrated improved outcomes, and similar studies are ongoing in pancreas and prostate cancer (22, 23).

One of the repeated observations from initial basket studies has been the diversity of patient outcomes despite the sharing of a common genomic biomarker. To better understand the biologic underpinnings of this heterogeneity in response, basket trials have evolved to more routinely incorporate comprehensive tumor analysis. A recent basket study of an AKT inhibitor in AKT1-E17K-mutant advanced solid tumors illustrates the utility of this approach (24). Extensive molecular analysis led to the identification of specific genomic contexts that may condition response to AKT inhibition. This experience illustrates that relying solely on the presence or absence of a single mutation, in this case AKT1-E17K, may mean overlooking additional factors that inform optimal patient selection.

Genomic profiling of cancer has revealed that oncogenic mutations in a gene are often not limited to a single codon. Instead, recurrent mutations can be seen at multiple alleles, each potentially conferring distinct signaling properties and sensitivity to pharmacologic inhibition. This degree of complexity must be considered by designers of basket studies. For example, in a recent basket study evaluating the efficacy of pan-HER inhibition in tumors harboring activating mutations in HER2/3, both the specific HER2 mutation and tumor type affected response to HER inhibition (25). Like the AKT inhibitor trial, this study underscores that, in many cases, the benefits of genomically targeted therapy are conditioned by a multitude of factors. Evaluation within the context of basket studies will be necessary to unravel these biologic complexities.

The selection of a truly histology-agnostic biomarker in a basket trial can lead to rapid translation of a targeted therapy into the clinical setting, as seen with tropomyosin-related kinase (TRK) inhibitors. TRK fusions are pathogenic alterations that occur at high frequencies in several rare cancers but also occur in a wide array of common cancers, typically at frequencies of ≤1% (26). Importantly, these fusions confer exquisite sensitivity to targeted inhibition in a truly histology-agnostic manner. This observation enabled the development of larotrectinib, which is expected to be the first genomically targeted therapy approved for use based on mutation alone, regardless of tumor type (27). The example of larotrectinib also demonstrates how incorporating pediatric cancers into the earliest stages of clinical development can further accelerate eventual regulatory approval of a tumor-agnostic genomically selected therapy. This experience targeting TRK fusions supports the fundamental premise that some cancers may be best classified on the basis of a mutation and not site of origin, and it acts as a general validation of the basket study paradigm.

Although most basket trials to date have employed targeted, small-molecule inhibitors against a particular genomic alteration, the underlying approach of the basket study is relevant to other classes of cancer therapy, including immunotherapy. For example, the efficacy of immune check-point blockade relies, in part, on intrinsic tumor characteristics such as the cancer’s genomic landscape, specifically the absolute number of somatic mutations and the presence of microsatellite instability (28). A basket study testing PD-1 (programmed cell death protein 1) blockade in patients with mismatch-repair-deficient tumors confirmed tumor-agnostic activity and led to the regulatory approval of pembrolizumab for any mismatch-repair-deficient advanced cancer patient (29). This landmark decision marks the first time a therapy was approved for treatment of cancer based solely on the presence of specific genomic characteristics regardless of the underlying tumor type. This approval illustrates the expanding role for basket trials beyond the testing of singular genomic biomarkers and reinforces the potential clinical impact of this research paradigm.

WHAT TO TEST: SELECTING BIOMARKERS FOR EVALUATION IN BASKET STUDIES

The basket study relies on appropriate biomarker selection to ensure its success. As more basket trials have been conducted, our understanding of the critical factors necessary for designing a rigorous basket study has improved. This section reviews the characteristics of a biomarker that make it appropriate for evaluation in a basket study. Key considerations in biomarker selection are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Biomarker characteristics favoring a basket study versus a traditional tumor-specific studya

| Characteristic | Basket study | Traditional tumor-specific study |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence of biomarker | Low | >5% |

| Distribution across cancers | Wide | Limited |

| Testing for biomarker | Amenable to multiplexing (next-generation sequencing, etc.) | Requires dedicated test |

| Evidence supporting association of candidate biomarkers with response | Required | Required |

The biomarker for a basket study, in contrast to a tumor-specific study, should occur at a low frequency across a wide variety of cancers and be amenable to a multiplex assay.

Both types of studies require preclinical or clinical evidence supporting an association between the biomarker and therapeutic response.

Basket trials are best suited to assess the efficacy of targeting genomic alterations that occur at low frequencies across a wide variety of tumor types. Markers that occur at high frequencies within a smaller number of tumor types (e.g., BRAF V600 in melanoma) are still appropriate, but those that occur with >5% frequency in many tumor types may be better evaluated through multiple disease-specific studies. There are two reasons for this—one pragmatic and one biologic. First, for very rare mutations, a traditional disease-specific study is not feasible owing to insufficient patient enrollment. For example, the AKT1-E17K mutation is oncogenic but occurs at very low prevalence in multiple tumor types, present in only ~3% of breast cancers and even less common in endometrial, ovarian, cervical, lung, colorectal, and prostate cancers (30). Consequently, a basket trial becomes a systematic strategy to clinically validate the efficacy of AKT inhibition in patients with AKT1-E17K mutations. The second reason is related to our understanding that a tumor’s response to a particular therapy is conditioned by its lineage. As discussed further below (Biostatistical Considerations of Basket Studies), if a particular tumor type harbors a mutation at a high enough frequency, it makes sense to conduct a single-site trial without introducing the separate variables and complexity of a multi-histology study.

Basket trials rely on the ability to rapidly identify a wide range of genomic alterations in a single test, since evaluating patients for a specific low-incidence alteration is operationally inefficient and often impractical. The availability of large-panel next-generation sequencing has greatly facilitated the identification of these variants, both common and rare, in a single test. In contrast, single-analyte testing relies on clinicians to order separate tests for each patient, a cumbersome and often impractical process. At our institution, a single next-generation sequencing test called MSK-IMPACT allows clinicians access to comprehensive mutational profiling that can inform treatment decisions (31).

ASSESSING THE UTILITY OF GENOME-DRIVEN ONCOLOGY: A CRITICAL VIEW

As in any other new field of medicine, it is important that we constantly assess the effectiveness of genome-driven oncology and evaluate whether the early deliverables are ultimately living up to their promise. In fact, several such efforts to measure the impact of this approach have recently been undertaken, with conflicting results.

The SHIVA trial was one of the first modern, large-scale, histology-agnostic studies conducted primarily to evaluate the effectiveness of genomically matching patients with refractory metastatic cancers and with a particular molecular alteration to a targeted agent (32). More than 700 patients underwent biopsy and molecular profiling of their metastatic tumors. Those with a molecular alteration identified within one of three molecular pathways (hormone receptor, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, or RAF/MEK) were matched to either a molecularly targeted agent (experimental group) or routine therapy (control group). Each patient was assigned to one of 11 molecularly targeted agents, and the routine therapy was physician’s choice. The primary endpoint of the trial was progression-free survival (PFS). Ultimately, the authors did not find a difference in PFS between the matched and the unmatched groups and concluded that off-label use of molecularly targeted agents should be discouraged. However, the SHIVA trial’s design had several methodologic shortcomings. Critically, to accurately assess whether a particular targeted therapy is effective against its target (a genomic alteration), there must be strong preclinical or clinical evidence supporting an association between the presence of the biomarker and response. In other words, the tumor must depend on the targeted pathway. Furthermore, the therapy must potently inhibit its target. Unfortunately, many of the target-and-drug pairs defined by the SHIVA trial lacked this evidence. Patients were matched to a limited set of therapies available in France at the time, including hormonal therapies and drugs now known to incompletely or nonselectively inhibit their targets. Furthermore, patients were matched with inhibitors without a biologic rationale. For example, patients with alterations in RICTOR, which activates the mTORC2 complex, were matched to everolimus, an mTORC1 inhibitor. These and other methodologic concerns lead us to question whether the primary conclusions of SHIVA may be premature.

In contrast, the MOSCATO-01 trial offered patients at a major European drug development center the opportunity for comprehensive genomic profiling of their cancers and then, based on the results, potential enrollment to genomically matched phase I/II studies available at that same center (33). The study used patients as their own controls, comparing the PFS on the prior therapy (PFS1, or the control) to the PFS on the matched therapy (PFS2), an endpoint previously proposed as a means of evaluating efficacy of targeted therapy in a single-arm study (34). Ultimately, MOSCATO-01 found that 33% of patients matched to targeted therapy (8% of all profiled patients) achieved an extended PFS compared to their last treatment (PFS2:PFS1 ratio >1.3). This result rejected the prespecified null hypothesis and demonstrated the feasibility and potential effectiveness of a disciplined biomarker-target approach. The use of more comprehensive profiling, more stringent genomic matching criteria, and better purpose-built inhibitors may all help explain the difference in outcomes observed between SHIVA and MOSCATO-01.

Other recent studies have also demonstrated superior outcomes with genome-driven therapy compared to unmatched therapy (35, 36). These studies further reinforce that the careful selection of biomarker-drug pairs is required for the effective implementation of genome-driven oncology.

As the attempt to apply genome-driven medicine to a larger population of cancers has grown, so has the skepticism surrounding this approach. Efforts to broaden the benefits of molecularly targeted therapy have often failed, leading some to question the fundamental premise that identifying and targeting a particular gene are likely to continue resulting in clinical impact. Although we are beginning to see more concrete evidence of success both at the individual gene level and at a population scale, it is important we remain vigilant and constantly reassess our basic assumptions over the value of this approach. Moreover, as we cover below, the current system in which genomically driven studies are conducted contains many inefficiencies, and therefore, opportunities for improvement. We believe that the benefits of genome-driven oncology can be applied more broadly by improving the identification, design, and execution of these studies.

BIOSTATISTICAL CONSIDERATIONS OF BASKET STUDIES

The restructuring of the fundamental organizing principle of a clinical trial, turning from cancer type to genomic alteration, presents new challenges for the biostatistical design of these studies. Although the structure of these studies is based on the assumption that the genomic alteration rather than the tumor type is likely to be predictive of response to a targeted therapy, it has become clear that tumor lineage remains an important modifier of response. The first generation of basket studies addressed this issue by acting as a series of independent, phase II studies conducted in parallel, typically using a conventional two-stage design such as the Simon design. Thus, each tumor type (basket) enrolled an adequate number of patients so that efficacy could be independently evaluated. This approach has several potential drawbacks, including higher false-positive rates than a typical phase II study, lack of evaluation for a potential relationship between baskets, and lack of evaluation for homogeneity of response.

From now on, biostatistical considerations will become increasingly important in clinical trials applying genome-driven oncology, especially as these studies begin to be used to support regulatory approvals. One important concern when employing the multiple independent two-stage designs utilized by the first generation of basket studies is that this multiple hypothesis testing may lead the investigator to incorrectly conclude that activity is present in one study arm. Given enough baskets, or study arms, a therapy might show a statistically significant effect by chance alone (i.e., a false positive). For example, as noted by Cunanan and colleagues (37), in a study with five disease cohorts (baskets) where each has a 5% false-positive rate, the cumulative chance that an ineffective drug will be declared effective is ~23%—a rate that would be considered unacceptably high in a traditional phase II study. Increasing the number of baskets further exacerbates this false-positive rate. By adjusting the decision rules or sample size within each basket, investigators can limit the overall false-positive rate.

Basket trials that are designed as multiple independent Simon two-stage studies also limit the ability to account for the interrelationship between the tumor-defined cohorts. This is because these designs do not incorporate the potential inherent interconnectedness among the baskets. Intuitively, a drug that is clearly efficacious in one tumor type raises our expectations that it will be effective in another. This potential correlation of efficacy could be harnessed during trial design. For example, the aggregation of efficacy data from a group of disease cohorts might allow for interim analysis and conclusion development more quickly, with fewer patients. Similarly, the use of statistical modeling can enable efficacy information to be shared among the baskets, improving efficiency and thereby theoretically allowing for enrollment of fewer patients (37). Ultimately, the field of biostatistics is rapidly evolving new designs for the era of tumor-agnostic precision oncology studies to address these potential shortcomings. These improvements will help ensure that the data derived from these increasingly important studies will have the statistical reliability and generalizability that we have come to expect from evidence-based medical practice.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS IN PRECISION ONCOLOGY STUDIES

We have laid out a framework that we believe is necessary both to successfully navigate the scientific challenges and to broaden the scope and applicability of genome-driven oncology. Equally important will be improving the way we test genomic hypotheses that come out of this framework in the clinic. We will need to be able to sequence patients, understand the clinical significance of the results, notify stakeholders of opportunities to act on these results, enroll patients to relevant studies, and finally interpret the outcome and iterate as necessary. Critical evaluation of each step in this chain identifies immediate opportunities for improvement that, when implemented in aggregate, offer the potential to dramatically increase the scope and ambition of hypotheses we can test in the clinic.

Initial efforts within individual institutions using broad-scale tumor sequencing to drive enrollment to targeted therapy studies revealed disappointing genomic match rates, often in the 4–13% range (38). One possible explanation is the clinician’s limited ability to interpret genomic testing results. Even at our large comprehensive cancer center, treating physicians misinterpreted the presence or absence of actionable mutations in a sizable minority of patients. To address this need, several large “knowledgebases” that aggregate and annotate the clinical significance of somatic variants have emerged (Table 2). These knowledgebases differ in their depth, scope, and capabilities. Our institution (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center) has developed OncoKB, a comprehensive, expert-guided precision oncology knowledgebase (39). To date, OncoKB has annotated >3,700 alterations in 476 cancer-associated genes. It also includes clinical and therapeutic information curated from multiple unstructured information resources, including information on biomarker-guided use of FDA-approved therapies, National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, disease-specific expert and advocacy group recommendations, and medical literature. By integrating annotated genomic data with their functional and therapeutic implications, OncoKB and similar resources act as clinical support tools to aid clinicians in interpreting their patient’s tumor mutational profile, and thus, in making informed treatment decisions.

Table 2.

Currently available somatic knowledgebases to help the oncologist identify the right treatment

| Knowledgebase | Genes annotated | Tumor-specific annotations | Community contributions/open source | Clinical guideline integration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Portal (Broad Institute) | 254 | yes | yes | yes |

| Precision Medicine Knowledgebase (Weill Cornell Medical College) | 163 | yes | yes | yes |

| Personalized Cancer Therapy (MD Anderson Cancer Center) | 32 | yes | no | no |

| Targeted Cancer Care (Massachusetts General Hospital) | 30 | yes | no | no |

| OncoKB (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center) | 476 | yes | yes | yes |

| Cancer Driver Log (The Ohio State University) | 62 | yes | no | no |

| My Cancer Genome (Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center) | 61 | yes | yes | yes |

| CIViC (Washington University in St. Louis) | 330 | yes | yes | yes |

New and more robust methods are needed to facilitate the connection between patients with actionable alterations and clinical trials targeting these often-rare genomic variants. Within our own institution, we have addressed this need by developing a system that enables the principal investigator of a precision oncology study to automatically identify, track, and recruit patients with qualifying genomic alterations (40). Rather than placing clinical trial recommendations into clinical sequencing reports, treating physicians receive automated, personalized notifications of genomically matched study opportunities for the individual patients they are treating, based on analysis of their sequencing reports. Notifications are not only generated when the initial sequencing report is signed out but also triggered by events that typically prompt a change in therapy, such as a computed tomography scan showing progressive disease or a rise in tumor markers on serial blood draws. Moreover, when a new study opens that targets an alteration for which a matched targeted therapy was previously unavailable, all previously sequenced patients with this alteration are identified, and the treating physician is again automatically notified. There are three keys to the success of this system. First, treating physicians do not need to be experts in interpreting the actionability of individual genomic alterations but instead can rely on those running the studies evaluating these individual alterations to identify treatment opportunities for their patients. Second, treating physicians are only notified of studies that are immediately available for their patient, a significant improvement over models that recommend dozens of studies even if the patient is not eligible, no spots are available, or the location is inaccessible. Finally, this system evolves as our understanding of the actionability of alterations improves; it provides physicians and their patients with up-to-date information and treatment opportunities at the moment they need them. The pairing of this genomic matching system with histology-agnostic genotype-driven basket studies has tremendously improved our center’s ability to treat patients with genomically matched therapy based on the results of their tumor sequencing.

Although the automated genomic matching and notification system developed at our center may not be immediately translatable in its current form to the broader oncology community, it clearly demonstrates the measures required to pursue an ambitious future for precision medicine. The field is urgently in need of a centralized genomic clearinghouse where the results of clinical genomic sequencing can be shared and matched in real time against the qualifying genomic alterations being targeted by individual studies. Unlike current study registries such as ClinicalTrials.gov, this system would permit a privacy-compliant two-way exchange between patients and study sponsors, who could indicate the specific genomic variants of interest and provide an enrollment pathway for qualifying patients.

Facilitating the identification of highly relevant genomically matched studies is only the first step. Patients must be able to readily access these studies. Although creation of histology-agnostic basket studies has significantly improved the likelihood that a genomically matched study exists for a particular patient, geographical constraints to study access remain an important barrier. The current generation of precision oncology studies is beginning to address this problem. Many study centers have programs to support enrolled patients’ travel and lodging. This approach allows investigators who have the most experience with an investigational drug to manage the patient while removing the patient’s financial barriers. Under this model, a small number of carefully selected and geographically dispersed sites act as referral centers for wide catchment areas. Although study sponsors must bear the cost of travel, this cost is generally much less than would be necessary to support the very large number of sites required to avoid the need for travel.

Alternatively, an increasing number of studies have adopted a “just in time” (JIT) study activation model. Under this system, once a patient with a relevant genomic alteration is identified, the study is rapidly opened at the site where the patient is already being treated. The study is brought to the patient rather than the patient to the study. Because the qualifying genomic alterations are typically very rare, many study sites enroll only one patient. The feasibility of this approach has been demonstrated by several trials, most notably by the Novartis Signature program. This program, essentially a collection of individual basket studies, offers genomically matched therapy under a JIT activation model to any physician and patient who wish to participate. In under two years, 368 patients with rare genomic variants have been treated at 167 unique sites (16 academic, 151 community). The ability of studies using JIT enrollment models to access patients treated in community (nonacademic) sites, where most cancer patients continue to be treated, is particularly important (41).

In addition to exploration of new enrollment models, there has been a move toward consolidation of multiple studies with genomically selected subjects into larger protocols, referred to as “master,” “umbrella,” or “molecular allocation” studies. These protocols generally offer multiple therapeutic options matched to the patient’s individual tumor genome. Several of these studies, such as I-SPY 2 (NCT01042379), Lung-MAP (NCT02154490), ALCHEMIST (NCT02194738), and BATTLE-2 (NCT01248247), have explored genomically defined subtypes of specific cancers. Some of these disease-specific studies that evaluate sufficiently common targets have even incorporated randomization against standard or “unmatched” therapy (42, 43). Master protocols can also offer treatment across a variety of tumor types and essentially become a collection of individual basket studies. Examples of this approach include NCI-MATCH (NCT02465060), MyPathway (NCT02091141), and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry (TAPUR) (NCT02693535).

The most ambitious effort to date has been the NCI-MATCH study, which is anticipated to include >30 unique treatment arms assigned primarily on the basis of genomic selection criteria. Unlike many related efforts, NCI-MATCH incorporates centralized, highly multiplexed tumor genomic screening, with the plan to biopsy and sequence 5,000 patients. This feature has made NCI-MATCH particularly attractive to community oncologists, who might otherwise not have easy access to tumor genomic screening beyond sending material to large commercial laboratories. In fact, initial enrollment to NCI-MATCH resulted in 795 patients undergoing fresh tumor biopsies in the first three months, far exceeding even the most optimistic initial projections. Importantly, interim analysis of the first 645 successfully sequenced tumors indicates that genomic matches will be made for ~24% of patients, a figure that is anticipated to grow further as the number of study arms continues to expand. Identification of potentially actionable alterations in 1 in 4 advanced cancer patients biopsied through NCI-MATCH demonstrates that even though the individual genomic lesions are uncommon, in aggregate, they affect a high proportion of patients. Thus, NCI-MATCH illustrates the potential scope of this therapeutic strategy (44).

CONCLUSIONS

We are approaching an era when understanding a tumor’s detailed molecular profile will become necessary to deliver the standard of care for all patients with advanced cancer. Exponential gains in the ability to profile cancers in real time and an increasing community adoption of these technologies are driving this new reality. The combination of these factors has finally allowed rigorous testing of a growing armamentarium of selective drugs against both common and rare genomic alterations. Although we have already achieved many tangible gains, targeting genomic alterations in both the tumor-lineage-dependent and -independent contexts, we have yet to fully capitalize on this approach. Histology-agnostic basket trials enrolling genomically selected subjects represent one important research tool for the efficient generation of knowledge needed to deliver clinically valuable therapies. However, basket trials are only one component of the larger infrastructure required to continue making progress in genome-driven oncology. Improvements in biomarker selection, biostatistical design, genomic knowledgebase development, patient matching, and enrollment models of genome-driven oncology care are needed to translate our genomic knowledge into clinically meaningful outcomes.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Dr. Hyman has consulted for Atara Biotherapeutics, Chugai Pharma, CytomX Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Hyman has received research support from Puma Biotechnology, Loxo Oncology, and AstraZeneca.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Schram AM, Berger MF, Hyman DM. 2017. Precision oncology: charting a path forward to broader deployment of genomic profiling. PLOS Med 14(2):e1002242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Druker BJ, Guilhot F, O’Brien SG, et al. 2006. Five-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med 355(23):2408–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bower H, Björkholm M, Dickman PW, et al. 2016. Life expectancy of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia approaches the life expectancy of the general population. J. Clin. Oncol 34(24):2851–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. 2001. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N. Engl. J. Med 344(11):783–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, et al. 2010. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med 363(9):809–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. 2004. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N. Engl. J. Med 350(21):2129–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Roock W, De Vriendt V, Normanno N, et al. 2011. KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, and PTEN mutations: implications for targeted therapies in metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet Oncol 12(6):594–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyman DM, Taylor BS, Baselga J. 2017. Implementing genome-driven oncology. Cell 168(4):584–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Food and Drug Administration. Approved drugs—FDA grants accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for first tissue/site agnostic indication https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm560040.htm

- 10.Kim ES, Herbst RS, Wistuba II, et al. 2011. The BATTLE trial: personalizing therapy for lung cancer. Cancer Discov 1(1):44–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu S, Lee JJ. 2015. An overview of the design and conduct of the BATTLE trials. Chin. Clin. Oncol 4(3):33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang MT, Asthana S, Gao SP, et al. 2016. Identifying recurrent mutations in cancer reveals widespread lineage diversity and mutational specificity. Nat. Biotechnol 34(2):155–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, et al. 2013. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature 502(7471):333–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. 2011. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N. Engl. J. Med 364(26):2507–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, et al. 2015. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N. Engl. J. Med 372(1):30–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brose MS, Cabanillas ME, Cohen EEW, et al. 2016. Vemurafenib in patients with BRAF(V600E)-positive metastatic or unresectable papillary thyroid cancer refractory to radioactive iodine: a non-randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 17(9):1272–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tiacci E, Park JH, De Carolis L, et al. 2015. Targeting mutant BRAF in relapsed or refractory hairy-cell leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med 373(18):1733–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Planchard D, Besse B, Groen HJM, et al. 2016. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with previously treated BRAF(V600E)-mutant metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: an open-label, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 17(7):984–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hyman DM, Puzanov I, Subbiah V, et al. 2015. Vemurafenib in multiple nonmelanoma cancers with BRAF V600 mutations. N. Engl. J. Med 373(8):726–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Emile J-F, et al. 2013. Dramatic efficacy of vemurafenib in both multisystemic and refractory Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring the BRAF V600E mutation. Blood 121(9):1495–1500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaufman B, Shapira-Frommer R, Schmutzler RK, et al. 2015. Olaparib monotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation. J. Clin. Oncol 33(3):244–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robson ME, Im S-A, Senkus E, et al. 2017. OlympiAD: Phase III trial of olaparib monotherapy versus chemotherapy for patients (pts) with HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (mBC) and a germline BRCA mutation (gBRCAm). J. Clin. Oncol 35(Suppl.):LBA2501 (Abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, et al. 2016. Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med 375(22):2154–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyman DM, Smyth LM, Donoghue MTA, et al. 2017. AKT inhibition in solid tumors with AKT1 mutations. J. Clin. Oncol 35(20):2251–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hyman DM, Piha-Paul SA, Rodon J. 2017. Neratinib in HER2- or HER3-mutant solid tumors: SUMMIT, a global, multi-histology, open-label, phase 2 “basket” study Presented at Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res., June 2–6, Chicago, IL. Abstr. CT001 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stransky N, Cerami E, Schalm S, et al. 2014. The landscape of kinase fusions in cancer. Nat. Commun 5:4846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyman DM, Laetsch TW, Kummar S, et al. 2017. The efficacy of larotrectinib (LOXO-101), a selective tropomyosin receptor kinase (TRK) inhibitor, in adult and pediatric TRK fusion cancers. J. Clin. Oncol 35(Suppl.):LBA2501 (Abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. 2015. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med 372(26):2509–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, et al. 2017. Mismatch-repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 357(6349):409–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bleeker FE, Felicioni L, Buttitta F, et al. 2008. AKT1(E17K) in human solid tumours. Oncogene 27(42):5648–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH, et al. 2017. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat. Med 23(6):703–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le Tourneau C, Delord J-P, Gonçalves A, et al. 2015. Molecularly targeted therapy based on tumour molecular profiling versus conventional therapy for advanced cancer (SHIVA): a multicentre, open-label, proof-of-concept, randomised, controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 16(13):1324–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Massard C, Michiels S, Ferté C, et al. 2017. High-throughput genomics and clinical outcome in hard-to-treat advanced cancers: results of the MOSCATO 01 trial. Cancer Discov 7(6):586–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Von Hoff DD, Stephenson JJ, Rosen P, et al. 2010. Pilot study using molecular profiling of patients’ tumors to find potential targets and select treatments for their refractory cancers. J. Clin. Oncol 28(33):4877–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsimberidou A-M, Wen S, Hong DS, et al. 2014. Personalized medicine for patients with advanced cancer in the phase I program at MD Anderson: validation and landmark analyses. Clin. Cancer Res 20(18):4827–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kris MG, Johnson BE, Berry LD, et al. 2014. Using multiplexed assays of oncogenic drivers in lung cancers to select targeted drugs. JAMA 311(19):1998–2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cunanan KM, Gonen M, Shen R, et al. 2017. Basket trials in oncology: a trade-off between complexity and efficiency. J. Clin. Oncol 35(3):271–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schram AM, Reales DN, Cambria R. 2017. Oncologist use and perception of large panel next generation tumor sequencing. Ann. Oncol 28:2298–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chakravarty D, Gao J, Phillips S, et al. 2017. OncoKB: a precision oncology knowledge base. JCO Precis. Oncol 1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eubank MH, Hyman DM, Kanakamedala AD, et al. 2016. Automated eligibility screening and monitoring for genotype-driven precision oncology trials. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc 23(4):777–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lynam EB, Leaw J, Wiener MB. 2012. A patient focused solution for enrolling clinical trials in rare and selective cancer indications: a landscape of haystacks and needles. Drug Inf. J 46(4):472–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park JW, Liu MC, Yee D, et al. 2016. Adaptive randomization of neratinib in early breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med 375(1):11–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rugo HS, Olopade OI, DeMichele A, et al. 2016. Adaptive randomization of veliparib-carboplatin treatment in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med 375(1):23–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Conley BA, Gray R, Chen A, et al. 2016. Abstract CT101: NCI-molecular analysis for therapy choice (NCI-MATCH) clinical trial: interim analysis. Cancer Res 76(14 Suppl.):CT101 (Abstr.) [Google Scholar]