Highlights

-

•

BioAider is an efficient tool for high-throughput analysis of viral genomes.

-

•

BioAider monitors viral variation that facilitates epidemic control of COVID-19.

-

•

14 substitution hotspots in SARS-CoV-2 genome indicates viral polymorphism.

-

•

NSP13-Y541C was found to be a crucial substitution key viral replication.

-

•

The unique SSRX repeats on N protein suggests the animal origin of SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords: BioAider, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Sustainable development, Mutant hotspots, SR-rich region

Abstract

The novel human coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) causes the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic worldwide. Control of COVID-19 pandemic is vital for public health and is the prerequisite to maintain social stability. However, the origin and transmission route of SARS-CoV-2 is unclear, bringing huge difficult to virus control. Monitoring viral variation and screening functional mutation sites are crucial for prevention and control of infectious diseases. In this study, we developed a user-friendly software, named BioAider, for quick sequence annotation and mutation analysis on large-scale genome-sequencing data. Herein, we detected 14 substitution hotspots within 3,240 SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences, including 3 groups of potentially linked substitution. NSP13-Y541C was crucial substitution which might affect the unwinding activity of the viral helicase. In particular, we discovered a SR-rich region of SARS-CoV-2 distinct from SARS-CoV, indicating more complex replication mechanism and unique N-M interaction of SARS-CoV-2. Interestingly, the quantity of SSRX repeat fragments in SARS-CoV-2 provided further evidence of its animal origin. Overall, we developed an efficient tool for rapid identification of viral genome mutations which could facilitate viral genomic studies. Using this tool, we have found critical clues for the transmission route of SARS-CoV-2 which would provide theoretical support for the epidemic control of pathogenic coronaviruses.

1. Introduction

The severe pandemic of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by a 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) which was first detected and characterized at the end of 2019 (Wu et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). Later, the name of this virus was suggested as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) (Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy, 2020). SARS-CoV-2 is a new pathogen showing high infectiousness, fast spread, partial asymptomatic infection, and other new features (Sanche et al., 2020; Wang, Tong et al., 2020). At present, the virus has been detected in most countries and regions around the world, threatening public health, normal social life, and economy. Effective control and dealing with the COVID-19 could reduce the impact of the pandemic on the economy which is important for the sustainable development of society (Rahman et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 has infected more than ten million people with about 600,000 deaths worldwide as of July 19th, 2020 (https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/). Compared with rural areas, the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in urban megacities is more serious (Antony Aroul, Velraj, & Haghighat, 2020). Current research shows that the virus is likely to spread through aerosol transmission, especially in the crowded place and enclosed space (Berlanga et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2019). Most patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 mainly present lower respiratory tract infections, accompanied by fever, dry cough, dyspnea (Huang et al., 2020). So far, there is no specific drug to treat SARS-CoV-2 infection and the vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 is still on the way. Therefore, blocking the transmission of the virus is of great importance for disease prevention and pandemic control (Megahed & Ghoneim, 2020). However, most key features of SARS-CoV-2, such as its origin and intermediate hosts, are still unclear, leading to difficulty in the control of virus spread. Considering the complicated interspecies and community transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the prevention and control of the epidemic requires the joint efforts of multiple industries (Xu, Luo, Yu, & Cao, 2020).

Coronaviruses are enveloped virus with a non-segmented positive-sense RNA genome which is the largest genome among all RNA viruses (Rota et al., 2003). The first open reading frame (ORF) encodes a polyprotein 1ab (pp1ab, ORF1ab) and approximately occupies the first two-thirds of the genome, while the remainder are structural and non-structural proteins (Song et al., 2019). The pp1ab is further hydrolyzed into 16 non-structural proteins (NSP1 ∼ NSP16) by one or two papain-like protease (PLPs) in NSP3 and 3C-like protease (3CLpro) in NSP5, which is required for viral RNA replication and transcription (Fehr & Perlman, 2015; Ziebuhr, 2005). For these non-structural proteins in pp1ab, NSP2 can inhibit two host proteins of PHB1 and PHB2, which play an important role in viral infection (Cornillez-Ty, Liao, Yates, Kuhn, & Buchmeier, 2009). The PLPs of NSP3 hydrolyze the N-terminal of pp1ab to NSP1 ∼ NSP4, and 3CLpro of NSP5 binds 11 conserved Q-S dipeptide sites in pp1ab to produce 12 mature non-structural proteins (NSP5 ∼ NSP16) (Fehr & Perlman, 2015; Lei, Kusov, & Hilgenfeld, 2018). NSP12, also known as the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), is a key component in the replication and transcription cycle of coronaviruses (Subissi et al., 2014). Currently, RdRp is considered to be the main target of antiviral drugs for SARS-CoV-2 (Gao et al., 2020). NSP13 owns NTPase/Helicase activity and can unwind double-stranded RNA and DNA helix (Jang, Lee, Yeo, Jeong, & Kim, 2008). Due to the conservation of NSP13 in all coronaviruses species, it is considered as an ideal target for the development of antiviral drugs for SARS-CoV (Jia et al., 2019; Shum & Tanner, 2008). The main four structural proteins of coronaviruses are spike protein (S), small envelope protein (E), membrane protein (M) and nucleocapsid protein (N) (Cui, Li, & Shi, 2019). S protein interacts with cellular receptors to mediate cell membrane fusion, allowing viruses to enter host cells (Li, 2016). E and M proteins are involved in the assembly of the virus, which is related to the formation and release of the viral envelope, N protein plays an important role in virus replication and pathogenesis (Li, 2016; Schoeman & Fielding, 2019).

Based on seven conserved replicase domains in pp1ab (polyprotein-1ab) for the classification of coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the Sarbecovirus subgenus of the genus Betacoronavirus in the subfamily Orthocoronavirinae together with human SARS-CoV and various bat SARSr-CoVs (SARS-related CoVs), and SARS-CoV-2 is highly similar to bat coronavirus Bat-CoV-RaTG13 genetically (International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses Executive, 2020; Zhou, Yang et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). Similar to SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 uses the angiotensin converting enzyme II (ACE2) as its receptor, while the serine protease TMPRSS2 plays an important role in activating spike (S) protein (Hoffmann et al., 2020). Some novel features of SARS-CoV-2 has been revealed, including a furin protease cleavage site in the Spike which may be related to viral transmissibility (Wang, Qiu et al., 2020). Recently, a novel bat-derived coronavirus RmYN02 with the similar furin insertion in the S was found, which implied the bat origin of SARS-CoV-2 (Zhou, Chen et al., 2020).

As RNA viruses, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) encoded by coronaviruses lacks the proofreading capability, leading to high mis-incorporation rate during replication even with the help of exoribonucleases like ExoN (Denison, Graham, Donaldson, Eckerle, & Baric, 2011). Together with the genome recombination events, the mis-incorporation could cause viral diversity and promote viral transmission (Hu et al., 2017). At the same time, in order to better adapt to the host, the virus usually mutates continuously under the selection pressure of the host. In particular, some non-synonymous substitution sites with high mutant frequency are often experience strong positive selection (Pond et al., 2006). Considering the continuous increase of infected people and the high variability of the virus, it is important to pay attention to the genomic changes of SARS-CoV-2. Recently, 7 substitution hotspots in SARS-CoV-2, ORF1ab-G10818T (ORF1ab-L3606F), ORF1ab-C8517T, ORF3a-G752T (ORF3a-G251V) S-A1841G (D614G), G171T (Q57H), ORF8-T251C (ORF8-L84S) and N-GGG608_609_610AAC (N-RG203_204KR) have been reported, (Capobianchi et al., 2020; Ceraolo & Giorgi, 2020; Issa, Merhi, Panossian, Salloum, & Tokajian, 2020; Wang, Liu et al., 2020). In addition, the non-synonymous substitutions of ORF3a-G251V and ORF8-L84S both cause the changes of amino acid (aa) polarity, which may affect the conformation of the protein and lead to function alteration (Ceraolo & Giorgi, 2020).

Despite these recent discoveries, in order to deal with the continuous variation of SARS-CoV-2 and the accumulation of sequencing data, methods for quick and efficient analysis of the mutation features and substitution hotspots of SARS-CoV-2 genome are urgently required. However, tools for sequence alignment have been well developed, such as Clustal, Muscle or Mafft, but tools for the downstream sequence variation analysis are lacked. Although the analysis of a large number of variant sequences could be accomplished well through scripts, it is difficult for biological or clinical experts without bioinformatics and programming skills. Some tools such as MutPred can analyze variations by entering amino acid sequence, but unable to handle synonymous substitutions and consecutive nucleotide mutations like dinucleotide and trinucleotide substitution (Pejaver et al., 2017). In comparative genomic studies, it is very important to identify whether amino acid properties have changed when dealing with non-synonymous substitutions, which can help to identify some important mutations. In this respect, we have developed an interactive analysis tool, Bioinformatics Aider V1.0 (BioAider V1.0). BioAider shows high efficiency and convenience in gene annotation and mutation screening on multiple genome-sequencing data.

In this research, we collected 3,240 complete genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2 from 64 different countries and regions, with sampling time from December 24, 2019 to April 1, 2020. We conducted a detailed genome mutation analysis using BioAider. We identified 14 substitution hotspots and 3 groups of possible linkage substitutions. Especially, we found distinctive polymorphism on SR-rich region of N protein in SARS-CoV-2 and related coronaviruses in other animals. Our work develops a new tool for recognition of the variation and evolution of SARS-CoV-2, contributes to research the replication and pathogenic mechanism of SARS-CoV-2, and provides further evidence for the animal origin of SARS-CoV-2.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Working principle of fast annotation and mutation analysis in BioAider

BioAider provides a convenient function for annotation on homologous sequence. Users can import the aligned complete genome sequence dataset, and adjust the reference sequence for gene extraction to the forefront of the sequence dataset. With the related gene information of reference sequence input in the input box, including gene name, start string and end string separated by comma, BioAider can extract genes and annotation from a large number of sequences in batches. Notably, the length of start string or end string is not limited, but it should be unique in the reference sequence.

For mutation analysis, BioAider will scan all the codons in the aligned sequence, using the first sequence in the dataset as the reference sequence. BioAider can identify five different mutation types (synonymous, non-synonymous, insert, deletion and termination) based on the codon method. It can distinguish the changes in properties of amino acid when dealing with non-synonymous substitutions. Then, it will locate the position of the corresponding base in the mutated codon, so it can identify multiple types of mutation at the same site, including dinucleotide and trinucleotide substitutions. Next, it summarizes all the mutation sites with corresponding frequency and strains, and if users choose to generate the frequency distribution of synonymous or non-synonymous sites, BioAider will directly generate the results in vector format image. Of note, the frequency distribution map does not include those sites that are both synonymous and non-synonymous substitution, because such sites cannot determine the common substitution frequency.

2.2. Mutation analysis of SARS-CoV-2

The 3,240 complete genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2 with high quality of sequencing were downloaded from GISAID (https://www.gisaid.org/), and the reference genome sequence of SARS-CoV-2 (NC_045512.2) for ORF annotation was from GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank). All the viral strains used in this study were listed in Table S1. Multiple sequence alignment of genomic sequences of SARS-CoV-2 were accomplished using Mafft v7.407 (Katoh & Standley, 2013; Zhang et al., 2020). The annotation and extraction of codon genes of these 3,240 SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences using BioAider V1.0. We extracted 11 continuously coding genes based on the annotation information of NC_045512.2, including ORF1ab, S, ORF3a, E, M, ORF6, ORF7a, ORF7b, ORF8, N and ORF10. Then we used Muscle program in MEGA v7.0.14 to align these coding genes based on codons method (Kumar, Stecher, & Tamura, 2016).

We combined these 11 continuously coding genes to tandem sequence in BioAider and used it to represent the complete genome sequence of SARS-CoV-2 for subsequent analysis. Among all the early sampled virus strains (Dec 24, 2019 to Dec30, 2019), genome of the viral strain with GISAID ID EPI_ISL_402119 (sampled in Dec30, 2019) existed most frequently (65 strains sequence were same with EPI_ISL_402119) in the 3,240 sequenced strains and appears in multiple regions. Therefore, the strain of EPI_ISL_402119 was used as the reference sequence for genome variation analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in BioAider. For these possible linkage substitution hotspots, we extracted corresponding viral sequences which contained these sites using BioAider.

2.3. Structure prediction of protein

The tertiary protein structure was downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (PDB, http://www.rcsb.org), and protein homology modeling was calculated by online tools SWISS-MODEL then using Chimera 1.10.2 to compare protein models (Pettersen et al., 2004; Waterhouse et al., 2018).

3. Results

3.1. Function overview and examples of BioAider

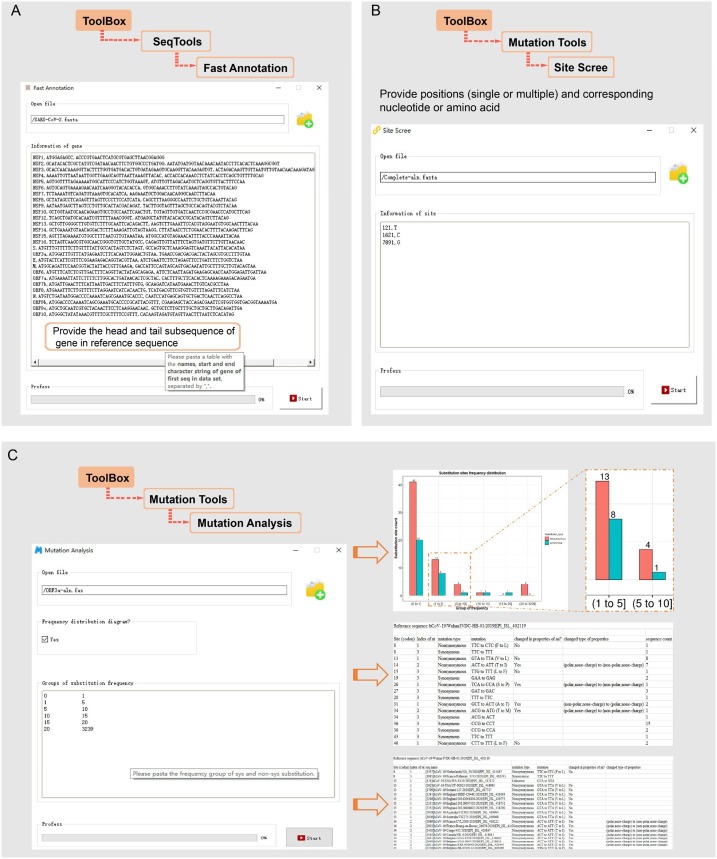

BioAider V1.0 was developed based on Python 3.7 and R 3.5, and used PySide2 for interface packaging. BioAider combines complex algorithms and fault-tolerant processing mechanisms inside, providing a user-friendly interface with prompts added to interface controls. The function of BioAider are divided into three main sections (Fig. 1 ). The SeqTools was used for common sequence processing, such as Split Sequence Fragmenet, Combine Gene, and Sequence Fast Annotation (Fig. 2 A). The section of Similar Analysis includes two functions that are generating sequence identity matrix and removing high similar sequence according to a specific threshold. Especially, BioAider owns the ability to acquire the identity of nucleotide and amino acid simultaneously, and provides optional features of gap compression in Sequence Identity Matrix. For the Mutation Tools, three nested functions are applied for genome variation analysis. The Site Counter can summarize the type, count and proportion of nucleotide (or amino acids) at each site for the aligned sequence datasets, the Site Scree is used for extract the sequence of the specific site (Fig. 2B). In particular, in addition to the highly summarized analysis results, the function of Mutation Analysis also provides high-quality vector graphics of synonymous or non-synonymous substitution frequency distribution for publication (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 1.

Function overview in BioAider.

Fig. 2.

Examples of sequence analysis by BioAider. (A) Fast sequence annotation based on aligned homologous sequence. (B) Site screen is used to search linkage disequilibrium substitution sites. (C) Parameter sets and result examples of mutation analysis.

3.2. Mutation sites in SARS-CoV-2 genomes

In this study, ‘substitution’ refers to synonymous or non-synonymous substitution, and ‘mutation’ includes all the genomic variance. The frequency of mutation (or substitution) refers to the number of mutant strains compared to the reference strain sequence in this study.

Compared with the early viral sampling strains (EPI_ISL_402119) in GISAID database, a total of 2,152 mutation sites (regardless of insertions or deletions) were identified in 3,239 SARS-CoV-2 sequenced whole genomes, accounting for 7.36 % of SARS-CoV-2 full-length gene (Table 1 ). The number of synonymous and non-synonymous substitution sites was counted as 784 (2.68 %) and 1335 (4.57 %), respectively. Among these non-synonymous substitution sites, 738 resulted in changes in amino acid properties. Besides, 12 sites contained both synonymous and non-synonymous substitution depending on the strains, and a total of 21 termination mutation sites were also detected. In all the coding genes, three with the most mutation sites were ORF1ab, spike (S) and nucleocapsid (N) gene, containing 1400, 296 and 168 mutation sites, respectively, accounting for 6.57 %, 7.75 % and 13.36 % in their corresponding gene length. The gene with the highest proportion of mutation sites was ORF10, containing 16 mutation sites in 114 bases which occupied 14.04 % of ORF10. All the mutation sites and viral strains of SARS-CoV-2 detected by BioAider in this study were summarized in Tables S2 and S3.

Table 1.

Mutation sites of SARS-CoV-2 based on 3239 sequenced strains.

| Genes | Length | Mutation sites | S(p) / N(p) / S-N(p) / Termination(p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count/Proportion | ||||

| ORF1ab | NSP1 | 540 | 48/8.88 % | 24(4.44 %)/24(4.44 %)/0/0 |

| NSP2 | 1914 | 168/8.77 % | 46(2.40 %)/122(6.37 %)/0/0 | |

| NSP3 | 5835 | 384/6.58 % | 130(2.23 %)/253 (4.33 %)/1(0.02 %)/0 | |

| NSP4 | 1500 | 99/6.60 % | 46(3.07 %)/53(3.53 %)/0/0 | |

| NSP5 | 918 | 42/4.58 % | 19(2.07 %)/23(2.51 %)/0/0 | |

| NSP6 | 870 | 71/8.16 % | 30(3.45 %)/41(4.71 %)/0/0 | |

| NSP7 | 249 | 19/7.63 % | 9(3.61 %)/10(4.02 %)/0/0 | |

| NSP8 | 594 | 27/4.55 % | 9(1.52 %)/16(2.69 %)/1(0.17 %)/1(0.17 %) | |

| NSP9 | 339 | 21/6.19 % | 11(3.24 %)/10(2.95 %)/0/0 | |

| NSP10 | 417 | 27/6.48 % | 10(2.40 %)/14(3.36 %)/1(0.24 %)/2(0.48 %) | |

| NSP12 | 2796 | 157/5.61 % | 58(2.07 %)/96(3.43 %)/0/3(0.11 %) | |

| NSP13 | 1803 | 109/6.05 % | 42(2.33 %)/67(3.72 %)/0/0 | |

| NSP14 | 1581 | 99/6.25 % | 41(2.59 %)/56(3.54 %)/1(0.06 %)/1(0.06 %) | |

| NSP15 | 1038 | 62/5.97 % | 18(1.73 %)/43(4.14 %)/1(0.10 %)/0 | |

| NSP16 | 894 | 67/7.49 % | 27(3.02 %)/39(4.36)/0/1(0.11 %) | |

| Count | 21,288 | 1400/6.57 % | 520(2.44 %)/867(4.07 %)/5(0.02 %)/8(0.04) | |

| S | 3819 | 296/7.75 % | 105(2.75 %)/186(4.87 %)/3(0.08 %)/2(0.05 %) | |

| ORF3a | 825 | 94/11.39 % | 31(3.75 %)/63(7.64 %)/0/0 | |

| E | 225 | 22/9.78 % | 9(4.00 %)/13(5.78 %)/0/0 | |

| M | 666 | 44/6.61 % | 28(4.21 %)/16(2.40 %)/0/0 | |

| ORF6 | 183 | 22/12.01 % | 4(2.18 %)/16(8.74 %)/0/2(1.09 %) | |

| ORF7a | 363 | 40/11.02 % | 12(3.31 %)/22(6.06 %)/1(0.27 %)/5(1.38 %) | |

| ORF7b | 129 | 11/8.52 % | 3(2.33 %)/7(5.42 %)/0/1(0.77 %) | |

| ORF8 | 363 | 39/10.75 % | 10(2.75 %)/26(7.16)/0/3(0.83 %) | |

| N | 1257 | 168/13.36 % | 58(4.61 %)/107(8.51 %)/3(0.24 %)/0 | |

| ORF10 | 114 | 16/14.04 % | 4(3.51 %)/12(10.53 %)/0/0 | |

| Complete | 29,232 | 2152/7.36 % | 784(2.68 %)/1335(4.57 %)/12(0.04 %)/21(0.07 %) | |

3.3. Substitution frequency distribution of synonymous or non-synonymous sites

To assess the overall substitution frequency of these mutated sites, we divided the substitution frequency into six different groups, and drew the frequency spectra of 2,119 substitution sites (784 synonymous and 1335 non-synonymous) of the 3,239 sequenced strains (Fig. 3 ). The result showed that the non-synonymous substitutions were always over synonymous ones except for the fifth group. Besides, a large number of sites with substitution frequencies between 1 and 5, and more than half of the substitution sites were observed in single strain only (the first group). We also found 60 sites owning a substitution frequency greater than 20, including 40 non-synonymous substitution sites and 20 synonymous substitution sites. The substitution frequency distribution of synonymous or non-synonymous sites for each codon gene are presented in Fig. S1.

Fig. 3.

Substitution frequency of synonymous or non-synonymous sites in SARS-CoV-2 genome. The frequency of X axis indicates the number of variant strains at the same substitution site, and the number one of first group represents that only one strain was mutated at this site. The Y axis represents the count of substitution sites corresponding to the range of frequency. The frequency spectra was drawn using BioAider by specifying six different groups.

3.4. Substitution hotspots in SARS-CoV-2 genomes

Totally, 2,119 substitution sites were detected in the 3,239 sequenced strains, and most of them showed a low substitution frequency. We defined the site with substitution frequency over 200 as the substitution hotspot. Thus far, 14 substitution hotspots were identified which distributed in ORF1ab, S, ORF3a, ORF8 and N gene (Fig. 4 ). Among these substitution hotspots, 10 sites were non-synonymous and 4 were synonymous. As for these non-synonymous substitution hotspots, 6 substitution sites caused a change on polarity or chargeability of amino acid. Especially, there was a trinucleotide substitution hotspot on the N gene and caused two amino acid changes.

Fig. 4.

Substitution hotspots in 3239 SARS-CoV-2 full genomic sequences. The value of the substitution site indicates the position on the corresponding gene, and showed the two main bases and ratio at substitution hotspots of 3239 sequenced strains. In particular, the substitution hotspots in N gene was a trinucleotide mutation. Round represented polar aa changed to non-polar aa, triangle represented non-polar aa changed to polar aa; diamond represented change in charge of polar aa.

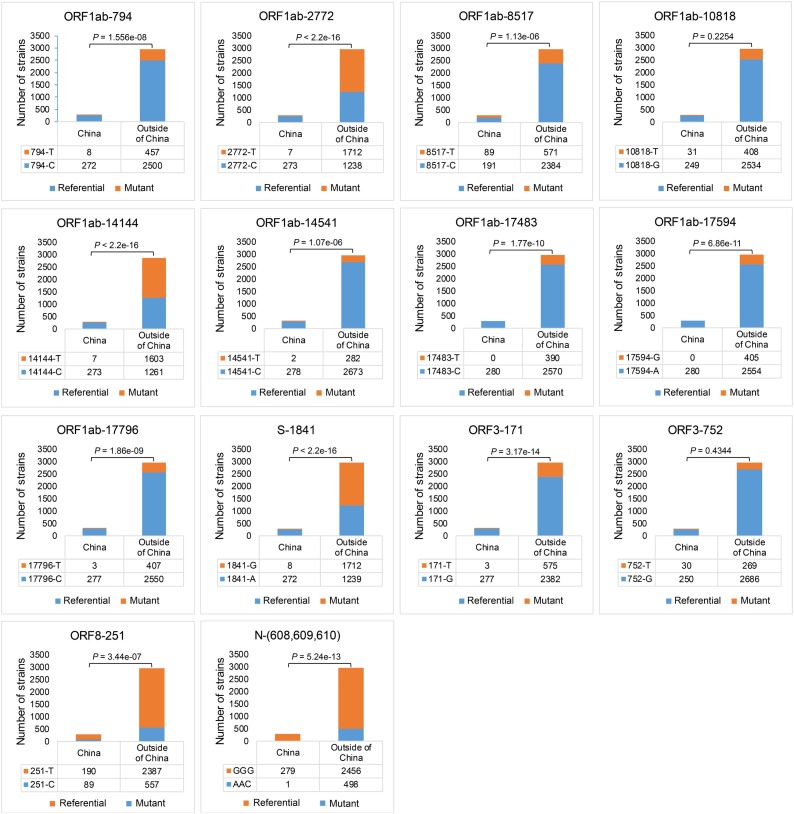

3.5. Spatial distribution characteristic of SARS-CoV-2 in each substitution hotspot

For all the substitution hotspots, we divided them into two geographical regions, China and outside of China, and studied the distribution differences of substitution hotspots between the two geographical areas (Fig. 5 ). As the result, except substitution hotspots of ORF1ab-10818 and ORF3a-752, mutant type and referential type in the 12 other substitution hotspots showed significant spatial distribution differences (p < 0.01, chi-square test) between China and outside of China. Furthermore, we found in substitution hotspots of ORF1ab-8517 and ORF8-251C, the mutant type (ORF1ab-8517T or ORF8-251C) owned a higher ratio and were more prevalent in China than outside of China, opposite to other 10 substitution hotspots.

Fig. 5.

Spatial distribution of referential types and mutant types in 14 substitution hotspots. Note strains which contained degenerate bases in substitution hotspots were culled, and spatial distribution differences of mutant type and referential type in hotspots was based on chi-square test.

3.6. Linkage among these substitution hotspots

Furthermore, we found some hotspots contains substitutions with similar patterns and frequency (Table 2 ), indicating potential connection among these substitution hotspots.Especially, we found 3 groups of possible linkage substitution. In order to refer to these substitution groups clearly, we used gene names and base positions to mark them. These linkage substitution hotspots were ORF1ab-2772 & ORF1ab-14144 & S-1841, ORF1ab-8517& ORF8-251 and ORF1ab-17483 & ORF1ab-17594 & ORF1ab-17796.

Table 2.

Sites with non-synonymous substitution frequency over 20 or synonymous substitution frequency over 200.

| Gene | Substitutions | AA change | Changes in properties of aa | Frequency/Proportion | Sampling date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF1ab | T225A | D75E | No | 29/0.89 % | 2020-01-21 to 2020-03-25 |

| C794T* | T265I | (polar, none-charge) to (non-polar) | 464/14.32 % | 2020-02-21 to 2020-03-31 | |

| G1132A | V378I | No | 73/2.25 % | 2020-01-18 to 2020-03-30 | |

| G1175A | G392D | (polar, none-charge) to (polar, negative-charge) | 68/2.10 % | 2020-02-25 to 2020-03-31 | |

| A2215G | I739V | No | 77/2.38 % | 2020-02-09 to 2020-03-29 | |

| C2293T | P765S | (non-polar) to (polar, none-charge) | 91/2.81 % | 2020-02-09 to 2020-03-29 | |

| G2626A | A876T | (non-polar) to (polar, none-charge) | 65/2.00 % | 2020-02-25 to 2020-03-31 | |

| C2772T* | No | No | 1719/53.06 % | 2020-01-28 to 2020-04-01 | |

| C2912T | P971L | No | 30/0.93 % | 2020-01-28 to 2020-03-25 | |

| C8517T* | No | No | 660/20.37 % | 2020-01-05 to 2020-03-26 | |

| T9212A | F3071Y | (non-polar) to (polar, none-charge) | 49/1,51 % | 2020-02-01 to 2020-03-23 | |

| G9832A | G3278S | No | 26/0.80 % | 2020-03-02 to 2020-03-29 | |

| A10058G | K3353R | No | 44/1.36 % | 2020-01-30 to 2020-03-21 | |

| G10818T* | L3606F | No | 439/13.55 % | 2020-01-17 to 2020-03-31 | |

| C11651T | S3884L | (polar, none-charge) to (non-polar) | 30/0.93 % | 2020-03-12 to 2020-03-23 | |

| C14144T* | P4715L | No | 1700/52.47 % | 2020-02 to 2020-04-01 | |

| C14541T* | No | No | 284/8.77 % | 2020-02-09 to 2020-03-29 | |

| C17483T* | P5828L | No | 390/12.04 % | 2020-02-20 to 2020-03-25 | |

| A17594G* | Y5865C | No | 405/12.50 % | 2020-02-20 to 2020-03-25 | |

| C17796T* | No | No | 410/12.65 % | 2020-01-19 to 2020-03-25 | |

| T18472C | F6158L | No | 28 | 2020-03-03 to 2020-03-25 | |

| C18734T | A6245V | No | 27 | 2020-03-12 to 2020-03-23 | |

| G19420T | V6474L | No | 24 | 2020-03-05 to 2020-03-20 | |

| Gene | Substitutions | AA change | Changed in properties of aa | Frequency/Proportion | Sampling date |

| S | A1841G* | D614G | (polar, negative-charge) to (polar, none-charge) | 1720/53.09 % | 2020-01-28 to 2020-04-01 |

| G2025C& | Q675H | (polar, none-charge) to (polar, positive-charge) | 7/0.22 % | 2020-03-03 to 2020-03-27 | |

| A2024G& | Q675R | (polar, none-charge) to (polar, positive-charge) | 1/0.03 % | 2020-03-04 | |

| AG2827CC | S943P | (polar, none-charge) to (non-polar) | 22/0.68 % | 2020-02-29 to 2020-03-20 | |

| ORF3a | G171T* | Q57H | (polar, none-charge) to (polar, positive-charge) | 578/17.84 % | 2020-02-21 to 2020-03-31 |

| C296T | A99V | No | 23/0.71 % | 2020-02-29 to 2020-03-31 | |

| G587T | G196V | (polar, none-charge) to (non-polar) | 48/1.48 % | 2020-02-25 to 2020-03-23 | |

| G752T* | G251V | (polar, none-charge) to (non-polar) | 299/9.23 % | 2020-01 to 2020-03-29 | |

| M | A8G | D3G | (polar, negative-charge) to (polar, none-charge) | 41/1.27 % | 2020-02 to 2020-03-30 |

| C524T | T175M | (polar, none-charge) to (non-polar) | 117/3.61 % | 2020-03-01 to 2020-03-29 | |

| ORF7a | C242T | S81L | (polar, none-charge) to (non-polar) | 25/0.77 % | 2020-03-07 to 2020-03-25 |

| ORF8 | G184C | V62L | No | 41/1.27 % | 2020-01-15 to 2020-03-25 |

| G184T | V62L | No | 3/0.09 % | 2020-03-18 to 2020-03-24 | |

| T251C* | L84S | (non-polar) to (polar, none-charge) | 646/19.94 % | 2020-01-05 to 2020-03-26 | |

| N | C38T | P13L | No | 29/0.89 % | 2020-02-27 to 2020-03-23 |

| G578T | S193I | (polar, none-charge) to (non-polar) | 27/0.83 % | 2020-01-21 to 2020-03-23 | |

| C581T | S194L | (polar, none-charge) to (non-polar) | 21/0.65 % | 2020-01-16 to 2020-03-21 | |

| C590T | S197L | (polar, none-charge) to (non-polar) | 49/1.51 % | 2020-02-25 to 2020-03-23 | |

| G605A | S202N | No | 34/1.05 % | 2020-01-25 to 2020-03-26 | |

| GGG608-609-610AAC* | R203K | No | 499/15.40 % | 2020-02-25 to 2020-04-01 | |

| G204R | (polar, none-charge) to (polar, positive-charge) |

Represents the substitution hotspots.

These sites were near furin cleavage region of S protein though the substitution frequency was below 20.

To test our hypothesis, we compared the number of strains between referential type and mutant type which synchronously mutated at the possible linkage substitution hotspots (Table 3 ). For each combination of possible linkage substitution hotspots, we found mutant type and referential type in accounts for more than 98 % of the population, it implied that the genetic variants in these combined substitution hotspots were not independent, but linkage.

Table 3.

The number of strains with possible linkage substitution among mainly mutant and referential strain.

| Combination of possible linkage substitution hotspots | Referential/Count | Mainly mutant/Count | Others |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORF1ab-2772 & ORF1ab-14144 & S-1841 | CCA/1504(46 %) | TTG/1690(52 %) | 45(2 %) |

| ORF1ab-8517& ORF8-251 | CT/2571(79 %) | TC/641(20 %) | 27(1 %) |

| ORF1ab-17483 & ORF1ab-17594 & ORF1ab-17796 | CAC/2824(87 %) | TGT/386(12 %) | 29(1 %) |

3.7. Vital substitution hotspots in SARS-CoV-2 NSP13

Since the 541th aa is one of the known key sites of NSP13 for binding to nucleic acids in SARS-CoV, the non-synonymous substitution hotspot of ORF1ab-Y5865C (NSP13-Y541C) in NSP13 probably affects the function of NSP13. We conducted protein model prediction of SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 by homology protein modeling. The result showed that closest protein model of NSP13 to SARS-CoV-2 was from SARS-CoV (PBD ID: 6JYT, 99.83 % amino acid identity). Notably, the tertiary structure of NSP13 were almost completely overlapping between SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV (Fig. 6 A). Besides, the 541th aa was relatively conservative in SARS-CoV-2 related animal coronaviruses (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Tertiary structure prediction of SARS-CoV-2 NSP13. (A) Tertiary structure superposition of NSP13 between SARS-CoV-2 (orange) and SARS-CoV (brown), the tertiary structure of SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 was based on model of SARS-CoV NSP13 (PBD ID: 6JYT) by homology modeling using gene sequence of EPI_ISL_402119. (B) The sequence alignment with partial amino acid of NSP13. SARS-CoV (AY291315.1), SARS-CoV-2_referential (EPI_ISL_402119), SARS-CoV-2_NSP13-P504L_Y541C (EPI_ISL_413456), Bat-CoV RaTG13 (MN996532.1), Bat-CoV_RmYN02 (EPI_ISL_412977), Pangolin-CoV (EPI_ISL_410721), MERS-CoV (KC875821.1).

3.8. Non-synonymous substitutions sites near furin cleavage region

Two non-synonymous substitution sites near the furin cleavage region of RRAR on S protein were identified (Fig. 7 and Table 2). There were 7 mutant strains with S-G2025C (S-Q675H) and one with S-A2024G (S-Q675R) among 3,239 sequenced strains. The 675th aa on S protein was the seventh amino acid upstream of RRAR, and we found S-Q675H and S-Q675R made original polar amino acids from no-charged to positively charged.

Fig. 7.

Non-synonymous substitution near the furin cleavage site of S.

3.9. Distinctive polymorphism in SR-rich fragment of SARS-CoV-2

We found a continuous variable area with non-synonymous substitutions from 183th to 204th aa on the N protein in SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 8 ), and there were 5 variable sites with non-synonymous substitutions frequency over 20, including a trinucleotide substitution which led to two consecutive aa substitutions of R203K and G204R (Table 2). Notably, there were 2 strains substituted on the 196th and 201th codons of SARS-CoV-2, too, but they were synonymous substitutions which did not cause amino acid substitutions (Table S2).

Fig. 8.

Polymorphic SR-rich region in SARS-CoV-2 N protein. The mutant strain in SARS-CoV-2 was represented using earliest sampled strain of this mutant type. The red and blue boxes represent the SSRX repeat domain.

The variable area was rich in Ser (S) and Arg (R) and contains SSRX repeat fragments. We compared the region among SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-2 related coronavirus, SARS-CoV and SARSr-CoV in this area (Fig. 8), and found that it was relatively conserved in SARS-CoV-2 related coronavirus, SARSr-CoV and SARS-CoV, but showed distinctive polymorphic in SARS-CoV-2. Interestingly, we found 4 SSRX repeat fragments in most strains of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-2 related coronavirus strains, but SARSr-CoV and SARS-CoV lacked the third SSRX repeat fragments due to one amino acid substitution. We found the number of SSRX repeat fragments well reflects the evolutionary relationship among SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-2 related coronavirus, SARSr-CoV and SARS-CoV. Especially, the substitution of two continuously amino acids on the last SSRX repeat fragments (203th and 204th in SARS-CoV-2) was exclusively observed in SARS-CoV-2.

To explore the polymorphism of SR-rich region (aa 183–204) on SARS-CoV-2 N protein, we intercepted the amino acids in this region. After culling some strains sequence containing degenerate bases in the region that could not be translated normally, we screened the SR-rich regions in the remaining 3,233 strains. The results showed the SR-rich regions in SARS-CoV-2 can be divided into 23 different types (Table 4 ), including the reference type. The two main types were the reference type (2561 strains) and the mutant type of N-R203K_G204R (494 strains). The majority of the 22 mutant types harbored only single-amino-acid substitution compared to the reference type, indicating that this region was relatively conserved among most SARS-CoV-2 strains. However, we could still find some distinctive polymorphism among different strains. The sampling date showed that most mutations existed in the 3233 recently sequenced strains, implying a constant evolution of the SR-rich region in SARS-CoV-2 genome.

Table 4.

The 23 types of SR-rich regions in N protein of SARS-CoV-2.

| Type | Amino acid sites and mutants |

First strain | Sampling date | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSRX-1 |

SSRX-2 |

SSRX-3 |

SSRX-4 |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 183 | 184 | 185 | 186 | 187 | 188 | 189 | 190 | 191 | 192 | 193 | 194 | 195 | 196 | 197 | 198 | 199 | 200 | 201 | 202 | 203 | 204 | Count | |||

| Reference type | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | P | G | S | S | R | G | 2561 | EPI_ISL_402123 | 2019-12-24 |

| N-R203K_G204R | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | P | G | S | S | K | R | 494 | EPI_ISL_412912 | 2020-02-25 |

| N-S197L | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | N | S | S | R | N | L | T | P | G | S | S | R | G | 49 | EPI_ISL_414623 | 2020-02-25 |

| N-S202N | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | P | G | S | N | R | G | 34 | EPI_ISL_416317 | 2020-01-25 |

| N-S193I | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | N | I | S | R | N | S | T | P | G | S | S | R | G | 27 | EPI_ISL_416389 | 2020-01-21 |

| N-S194L | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | N | S | L | R | N | S | T | P | G | S | S | R | G | 21 | EPI_ISL_406594 | 2020-01-16 |

| N-S188L | S | S | R | S | S | L | R | S | R | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | P | G | S | S | R | G | 6 | EPI_ISL_415708 | 2020-03-07 |

| N-S183Y | Y | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | P | G | S | S | R | G | 6 | EPI_ISL_417474 | 2020-03-12 |

| N-R195K | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | N | S | S | K | N | S | T | P | G | S | S | R | G | 6 | EPI_ISL_415650 | 2020-03-02 |

| N-R185C | S | S | C | S | S | S | R | S | R | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | P | G | S | S | R | G | 5 | EPI_ISL_416336 | 2020-02-01 |

| N-S190I | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | I | R | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | P | G | S | S | R | G | 4 | EPI_ISL_421358 | 2020-03-17 |

| N-S188P | S | S | R | S | S | P | R | S | R | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | P | G | S | S | R | G | 4 | EPI_ISL_414558 | 2020-03-06 |

| N-R191 L & N-R203K_G204R | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | L | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | P | G | S | S | K | R | 4 | EPI_ISL_417021 | 2020-03-15 |

| N-G200S | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | P | S | S | S | R | G | 2 | EPI_ISL_417508 | 2020-03-16 |

| N-N192K | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | K | S | S | R | N | S | T | P | G | S | S | R | G | 2 | EPI_ISL_417238 | 2020-03-03 |

| N-P199S | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | S | G | S | S | R | G | 1 | EPI_ISL_414379 | 2020-02-18 |

| N-P199T | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | T | G | S | S | R | G | 1 | EPI_ISL_419772 | 2020-03-13 |

| N-P199L | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | L | G | S | S | R | G | 1 | EPI_ISL_418677 | 2020-03-15 |

| N-T198I & N-R203K_G204R | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | N | S | S | R | N | S | I | P | G | S | S | K | R | 1 | EPI_ISL_419988 | 2020-03-23 |

| N-R203K | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | P | G | S | S | K | G | 1 | EPI_ISL_419890 | 2020-03-19 |

| N-S186F | S | S | R | F | S | S | R | S | R | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | P | G | S | S | R | G | 1 | EPI_ISL_418324 | 2020-03-11 |

| N-R191C | S | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | C | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | P | G | S | S | R | G | 1 | EPI_ISL_420598 | 2020-03-22 |

| N-S186Y | S | S | R | Y | S | S | R | S | R | N | S | S | R | N | S | T | P | G | S | S | R | G | 1 | EPI_ISL_416398 | 2020-02-02 |

Note: The mutation sites are in bold comparing with the reference strain.

4. Discussion

COVID-19 pandemic poses a great challenge to the healthy cities and societies, and its prevention and control requires cross-disciplinary cooperation and research, including biology, industry, medicine and computer information technology (Xu et al., 2020). Computational biology, big data and artificial intelligence are playing a more important role in daily monitoring, prevention and treatment of infectious diseases, contributing to maintaining the sustainable development of society (Liu & Li, 2020; Zhou, He, Cai, Wang, & Su, 2019). To deal with rapid variation of SARS-CoV-2, program tools for high-throughput analyses on big sequencing data of genome are of great importance for genomic and evolutionary studies. More importantly, simplicity of operation and high summary of analysis results could save a lot of time for researchers.

Some graphic-interface bioinformatics programs, such as MEGA, DNAMAN and Geneious, are commonly used to browse or align the sequences of genes and genomes, but they are not suitable for the mutation analysis of large-scale datasets (Kearse et al., 2012; Kumar et al., 2016). For instance, SNP-sites can screen the mutant sites in datasets of DNA sequences by sequence alignment with the reference sequence, but it cannot tell the types of those mutations (e.g. synonymous mutation or non-synonymous mutation) which are important for viral genome analyses (Page et al., 2016). In addition, SNP-sites is a command-line program which is not friendly to users not familiar with bioinformatic programs. Another program named MutPred is capable of analyzing amino acid sequences but not nucleic acid sequences, thus it cannot reveal the variance on viral genomes (Pejaver et al., 2017).

Here, we present BioAider, an efficient graphical tool for mutation analysis of viral genome. BioAider can process nucleic acid and amino acid sequence analysis in parallel. After several simple steps of operation including dataset input and parameter setup, BioAider will process the analyses automatically and outputs comprehensive and visualized graphs presenting all the information about the mutations in the input genomes, such as mutation type list (e.g. synonymous mutation, non-synonymous mutation, insertion, deletion or nonsense mutation), mutation frequency and changes in amino acid properties. Meanwhile, BioAider is designed for high-throughput analyses, and this interface makes it more efficient experience for the handling of bigdata. BioAider greatly improve the efficiency for genome variation analysis of SARS-CoV-2, contributing to the study of SARS-CoV-2 and the development of healthy smart cities. In addition, BioAider harbors a built-in database of all 25 amino acid codon systems (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Utils/wprintgc.cgi?) and can be used for the analyses of genomes from other organisms such as bacteria and archaea. The expansion and optimization of BioAider in the future will endow the software with more functions.

In this study, we conducted high-resolution analysis of mutations within SARS-CoV-2 genome based on 3240 sequenced strains using BioAider. 2,152 mutation sites among different strains were detected which accounted for 7.36 % of the complete genome. These mutation sites included 1,335 non-synonymous substitution sites, implying abundant variations in the genome of SARS-CoV-2. However, more than half of the mutation sites were only observed in a single strain of SARS-CoV-2 which was difficult to be distinguished from sequencing errors. Considering there were only 60 sites with substitution frequency above 20. Therefore, we speculated that there were no large-scale mutations in the sequencing strains we analyzed.

According to the spatial distribution analysis between strains of mutant types and referential type regarding the substitution hotspots, 12 of 14 sites showed significant distribution differences in China and outside of China, indicating different virus prevalence in the two regions and may evolve in different directions in the future. We also noticed mostly strains sampled in China were before Mar 2020, this was due to the epidemic of China has been roughly controlled in March. Considering these facts, we speculate that virus differentiation in and outside of China may attribute to human intervention. Besides, these non-synonymous substitution hotspots should be given more attention, they were most likely related to the phenotype of the virus. The latest study has discovered the strain with substitution of S-D614G could increases the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 (Korber et al., 2020).

In SARS-CoV NSP13, the 541th aa was critical for the protein function and double mutations of S539A/Y541A showed higher unwinding activity for nucleic acids binding (Jia et al., 2019). The amino acid identity of NSP13 between SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV was 99.83 % and their tertiary structure was almost completely overlapping, indicating that NSP13 541th aa is also a vital site for the function of SARS-CoV-2 NSP13. Notably, the mutant strain of NSP13-541C first appeared in the United States (sampled on Feb 20, 2020), and the United States was the country with the largest number and extremely high proportion of this mutant strains (316, 78 % of all the 405 mutant strains with NSP13-Y541C). We also noted that among the 711 strains sampled in the United States on Feb 20, 2020 and beyond, strains with NSP13-Y541C accounted for almost half of these strains. This fact indicates that NSP13-Y541C has gone through less negative selection pressure and even this variation may be beneficial. Therefore, we speculate that NSP13-Y541C improves the unwinding activity of NSP13 and promotes the replication of SARS-CoV-2, contributing to their rapid spread in the United States. However, further studies are required to reveal the detailed effect of substitution in 541th aa of SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 and whether the possible linkage substitution site of 504th aa plays a synergistic role in this process.

Among the potential linkage substitution hotspots identified in this study, ORF1ab-8517 and ORF8-251 were observed in a recent research (Ceraolo & Giorgi, 2020; Tang et al., 2020). Among the triple linkage substitution hotspots of ORF1ab-277, ORF1ab-14144 and S-1841, ORF1ab-C2772T belongs to synonymous substitution, while ORF1ab-C14144T caused the aa change of NSP12-P323L in interface region which is a bridge section connecting NiRNA (nidovirus RdRp-associated nucleo-tidyltransferase) and Fingers of RdRp (Gao et al., 2020). The 614th aa in S protein was located in the subdomain (SD) region downstream of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) on S1. We found that mutant strains with NSP12-323L & S-614G were popular in the world and owned more than half the frequency (52 %) in the population, indicating that this mutant was dominant in SARS-CoV-2. However, the functional impact of linkage substitution in these two sites is still unclear at present, and whether NSP12-323 and S-614 are related on specific function needed more experimental data to verify.

Previous studies have reported that SR-rich region in SARS-CoV is crucial for N protein multimerization and the interaction with membrane (M) protein (He, Dobie et al., 2004; He, Leeson et al., 2004). In the SR-rich region of N protein, there was only 2-aa difference between SARS-CoV-2 (referential type) and SARS-CoV. Therefore, the similar function of SR-rich region may exist in SARS-CoV-2, although there is no relevant research reported at present. Compared to SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 harbors one more SSRX repeat fragments in the 193th–196th aa of N protein. Previous research reported that the SR-rich region of SARS-CoV in 184th–196th aa was crucial for N protein multimerization and the deletion of this region completely would make N protein abolish the self-multimerization (He, Dobie et al., 2004). Besides, the protein fragment of ASSRSSSRSRGNSRN (SSRX or SRXX repeat fragments) may play an important role in SARS-CoV infection (Luo et al., 2005). We noted that SARS-CoV could be regarded as a deletion of SSRX in SR-rich region compared to SARS-CoV-2, and the transmission rate of SARS-CoV-2 was higher than SARS-CoV, thus, whether SR-rich region of SARS-CoV-2 plays an important role in this process is worth to explore. However, the research about SR-rich region in coronavirus was still limited at present. Especially, unlike SARS-CoV, the region in SARS-CoV-2 is still constantly evolving, implying that the N protein of SARS-CoV-2 may employ a more flexible replication mechanism and even interaction with M protein. A study reported that the N protein of SARS-CoV can specifically bind to heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) A1 and plays an important role in RNA replication and transcription, especially, the key binding region is in the SR-rich region of SARS-CoV N protein (aa 161-210), the interaction between human hnRNP A1 and SARS-N protein may be the key to SARS-CoV replication and transcription (Luo et al., 2005). Whether such a similar mechanism exists in SARS-CoV-2 is still unclear. However, in human cells, there are more than 20 hnRNPs has been discovered, and SR-rich region of SARS-CoV-2 showing distinctive polymorphism, whether the SARS-CoV-2 can bind to one of these hnRNPs needs more verification. It might provide a new hint in understanding the process of SARS-CoV-2 replication in human cells. Besides, the potential phenotype changes related to non-synonymous substitution hotspots on fourth SSRX repeat fragments of SARS-CoV-2 may be also worth attention.

In the hotspot screening, we have found several substitutions critical for viral replication potentially. For instance, the ORF1ab-C794T was located on NSP2 and NSP2 was reported to inhibit the host protein PHB1 and PHB2 which benefited viral replication, indicating that ORF1ab-C794T may affect viral replication (Cornillez-Ty et al., 2009). The ORF3a-G171T (Q57H) was located at the transmembranous domain of the 3a protein (Fig. S2). The 3a protein was reported to form ion channels on host cell membrane and enhance the membrane permeability which benefited SARS-CoV life cycle (Minakshi, Padhan, Rehman, Hassan, & Ahmad, 2014). Thus, ORF3a-G171T (Q57H) may affect the formation of ion channels and subsequently influence the viral replication. As for ORF3a-G752T (G251V), a recent analysis predicted that it was in an important functional domain and might be related to virulence, infectivity, ion channel formation and virus release (Issa et al., 2020). We also found several important sites for virus entry, though they showed lower substitution frequency in our research data. For instance, S-Q675H and S-Q675R near furin cleavage region possibly influence the cleavage of RRAR, a critical step for virus entry (Fig. 7). In addition, we also detected a strain with the mutation of S-R408I located in the RBD (Table S2) which was reported to play an important role in virus-receptor binding by a recent study (Saha, Banerjee, Tripathi, Srivastava, & Ray, 2020).

5. Conclusion

BioAider greatly simplifies annotation and genome variation analysis of large-scale sequences data. We initially revealed the variation characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and predicted the possible impact for some non-synonymous substitution hotspots using BioAider, contributing to study the formation mechanism and evolution of SARS-CoV-2. The distinctive polymorphism SR-rich region of N protein in SARS-CoV-2 provides a new clue to establish anti-virus strategy for viral replication. In this study, we could not include all the sequences of SARS-CoV-2 due to the rapid increase of the genomic data. More researches or real time analysis with relevant clinical data may contribute to the viral epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 and treatment of COVID-19. The BioAider software could help doctors or those who are not familiar with bioinformatics to analyze the viral genomes, which is conducive to prevention and control of the COVID-19 or similar viral infectious diseases.

6. Data accessibility

BioAider and all the updated versions are freely available to non-commercial users at https://github.com/ZhijianZhou01/BioAider/releases, and the detailed user manual is available from https://github.com/ZhijianZhou01/BioAider.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was jointly funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China

(grant numbers 32041001 and 81902070), National Key Research and Development Program of China (grantnumber 2017YFD0500104), the Provincial Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (grant numbers 2019JJ20004, 2019JJ50035, and 2020SK3001), and the Emergency Project of Prevention and Control for COVID-19 of Central South University (grant number 160260003).

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2020.102466.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Antony Aroul R.V., Velraj R., Haghighat F. The contribution of dry indoor built environment on the spread of coronavirus: Data from various Indian states. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2020;102371 doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlanga F.A., Liu L., Nielsen P.V., Jensen R.L., Costa A., Olmedo I., de Adana M.R. ). Influence of the geometry of the airways on the characterization of exhalation flows. Comparison between two different airway complexity levels performing two different breathing functions. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2020;53:101874. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2019.101874. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capobianchi M.R., Rueca M., Messina F., Giombini E., Carletti F., Colavita F.…Bartolini B. Molecular characterization of SARS-CoV-2 from the first case of COVID-19 in Italy. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceraolo C., Giorgi F.M. Genomic variance of the 2019-nCoV coronavirus. Journal of Medical Virology. 2020;92(5):522–528. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornillez-Ty C.T., Liao L., Yates J.R., 3rd., Kuhn P., Buchmeier M.J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nonstructural protein 2 interacts with a host protein complex involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and intracellular signaling. Journal of Virology. 2009;83(19):10314–10318. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00842-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of V. The species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: Classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nature Microbiology. 2020;5(4):536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., Li F., Shi Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2019;17(3):181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison M.R., Graham R.L., Donaldson E.F., Eckerle L.D., Baric R.S. Coronaviruses: An RNA proofreading machine regulates replication fidelity and diversity. RNA Biology. 2011;8(2):270–279. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.2.15013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr A.R., Perlman S. Coronaviruses: An overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2015;1282:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Yan L., Huang Y., Liu F., Zhao Y., Cao L.…Rao Z. Structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from COVID-19 virus. Science. 2020;368(6492):779–782. doi: 10.1126/science.abb7498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He R., Dobie F., Ballantine M., Leeson A., Li Y., Bastien N., Li X. Analysis of multimerization of the SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid protein. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;316(2):476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He R., Leeson A., Ballantine M., Andonov A., Baker L., Dobie F., Li X. Characterization of protein-protein interactions between the nucleocapsid protein and membrane protein of the SARS coronavirus. Virus Research. 2004;105(2):121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Kruger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S.…Pohlmann S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–280 e278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B., Zeng L.P., Yang X.L., Ge X.Y., Zhang W., Li B.…Shi Z.L. Discovery of a rich gene pool of bat SARS-related coronaviruses provides new insights into the origin of SARS coronavirus. PLoS Pathogens. 2017;13(11):e1006698. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y.…Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses Executive C. The new scope of virus taxonomy: Partitioning the virosphere into 15 hierarchical ranks. Nature Microbiology. 2020;5(5):668–674. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0709-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa E., Merhi G., Panossian B., Salloum T., Tokajian S. SARS-CoV-2 and ORF3a: Nonsynonymous mutations, functional domains, and viral pathogenesis. mSystems. 2020;5(3) doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00266-20. e00266–00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang K.J., Lee N.R., Yeo W.S., Jeong Y.J., Kim D.E. Isolation of inhibitory RNA aptamers against severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus NTPase/Helicase. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2008;366(3):738–744. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Z., Yan L., Ren Z., Wu L., Wang J., Guo J.…Rao Z. Delicate structural coordination of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus Nsp13 upon ATP hydrolysis. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019;47(12):6538–6550. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Standley D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2013;30(4):772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M., Moir R., Wilson A., Stones-Havas S., Cheung M., Sturrock S.…Drummond A. Geneious basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(12):1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korber B., Fischer W.M., Gnanakaran S., Yoon H., Theiler J., Abfalterer W.…Wyles M.D. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 spike: Evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei J., Kusov Y., Hilgenfeld R. Nsp3 of coronaviruses: Structures and functions of a large multi-domain protein. Antiviral Research. 2018;149:58–74. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F. Structure, function, and evolution of coronavirus spike proteins. Annual Review of Virology. 2016;3(1):237–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-042301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Li Y. Smart cities for emergency management. Nature. 2020;578(7796):515. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00523-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H., Chen Q., Chen J., Chen K., Shen X., Jiang H. The nucleocapsid protein of SARS coronavirus has a high binding affinity to the human cellular heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1. FEBS Letters. 2005;579(12):2623–2628. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megahed N.A., Ghoneim E.M. Antivirus-built environment: Lessons learned from Covid-19 pandemic. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2020;61 doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakshi R., Padhan K., Rehman S., Hassan M.I., Ahmad F. The SARS Coronavirus 3a protein binds calcium in its cytoplasmic domain. Virus Research. 2014;191:180–183. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page A.J., Taylor B., Delaney A.J., Soares J., Seemann T., Keane J.A., Harris S.R. SNP-sites: Rapid efficient extraction of SNPs from multi-FASTA alignments. Microbial Genomics. 2016;2(4):e000056. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pejaver V., Urresti J., Lugo-Martinez J., Pagel K.A., Lin G.N., Nam H.-J.…Radivojac P. MutPred2: Inferring the molecular and phenotypic impact of amino acid variants. bioRxiv. 2017:134981. doi: 10.1101/134981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C., Ferrin T.E. UCSF Chimera--A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pond S.L., Frost S.D., Grossman Z., Gravenor M.B., Richman D.D., Brown A.J. Adaptation to different human populations by HIV-1 revealed by codon-based analyses. PLoS Computational Biology. 2006;2(6):e62. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M.A., Zaman N., Asyhari A.T., Al-Turjman F., Alam Bhuiyan M.Z., Zolkipli M.F. Data-driven dynamic clustering framework for mitigating the adverse economic impact of Covid-19 lockdown practices. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2020;62 doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rota P.A., Oberste M.S., Monroe S.S., Nix W.A., Campagnoli R., Icenogle J.P.…Bellini W.J. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300(5624):1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha P., Banerjee A.K., Tripathi P.P., Srivastava A.K., Ray U. A virus that has gone viral: Amino acid mutation in S protein of Indian isolate of Coronavirus COVID-19 might impact receptor binding, and thus, infectivity. Bioscience Reports. 2020;40(5) doi: 10.1042/BSR20201312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanche S., Lin Y.T., Xu C., Romero-Severson E., Hengartner N., Ke R. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2020;26(7) doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeman D., Fielding B.C. Coronavirus envelope protein: Current knowledge. Virology Journal. 2019;16(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shum K.T., Tanner J.A. Differential inhibitory activities and stabilisation of DNA aptamers against the SARS coronavirus helicase. Chembiochem. 2008;9(18):3037–3045. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z., Xu Y., Bao L., Zhang L., Yu P., Qu Y.…Qin C. From SARS to MERS, thrusting coronaviruses into the spotlight. Viruses. 2019;11(1) doi: 10.3390/v11010059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subissi L., Imbert I., Ferron F., Collet A., Coutard B., Decroly E., Canard B. SARS-CoV ORF1b-encoded nonstructural proteins 12-16: Replicative enzymes as antiviral targets. Antiviral Research. 2014;101:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X., Wu C., Li X., Song Y., Yao X., Wu X.…Lu J. On the origin and continuing evolution of SARS-CoV-2. National Science Review. 2020 doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Liu Z., Chen Z., Huang X., Xu M., He T., Zhang Z. The establishment of reference sequence for SARS-CoV-2 and variation analysis. Journal of Medical Virology. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Qiu Y., Li J.Y., Zhou Z.J., Liao C.H., Ge X.Y. A unique protease cleavage site predicted in the spike protein of the novel pneumonia coronavirus (2019-nCoV) potentially related to viral transmissibility. Virologica Sinica. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12250-020-00212-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Tong J., Qin Y., Xie T., Li J., Li J.…He Y. Characterization of an asymptomatic cohort of SARS-COV-2 infected individuals outside of Wuhan, China. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A., Bertoni M., Bienert S., Studer G., Tauriello G., Gumienny R.…Schwede T. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2018;46(W1):W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y.M., Wang W., Song Z.G.…Zhang Y.Z. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C., Luo X., Yu C., Cao S.-J. The 2019-nCoV epidemic control strategies and future challenges of building healthy smart cities. Indoor and Built Environment. 2020;29(5):639–644. doi: 10.1177/1420326x20910408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Gao F., Jakovlić I., Zou H., Zhang J., Li W.X., Wang G.T. PhyloSuite: An integrated and scalable desktop platform for streamlined molecular sequence data management and evolutionary phylogenetics studies. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2020;20(1):348–355. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Feng G., Bi Y., Cai Y., Zhang Z., Cao G. Distribution of droplet aerosols generated by mouth coughing and nose breathing in an air-conditioned room. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2019;51 doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2019.101721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., He S., Cai Y., Wang M., Su S. Social inequalities in neighborhood visual walkability: Using street view imagery and deep learning technologies to facilitate healthy city planning. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2019;50 doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2019.101605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., Chen X., Hu T., Li J., Song H., Liu Y.…Shi W. A novel bat coronavirus closely related to SARS-CoV-2 contains natural insertions at the S1/S2 cleavage site of the spike protein. Current Biology. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W.…Shi Z.L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J.…Research T. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebuhr J. The coronavirus replicase. In: Enjuanes L., editor. Coronavirus replication and reverse genetics. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2005. pp. 57–94. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

BioAider and all the updated versions are freely available to non-commercial users at https://github.com/ZhijianZhou01/BioAider/releases, and the detailed user manual is available from https://github.com/ZhijianZhou01/BioAider.