Abstract

Background

A novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was reported in Wuhan, China late December 2019. The disease has as of the end of March 2020, affected over 35 countries (with over 570,000 cases and 26,000 deaths) worldwide. This includes the U.S., where cases are increasing by the thousands every day (100,000 cases with 1500 deaths as of April 2020). We set out to investigate new or increased stressful life events (SLEs) as a result of this pandemic in the U.S.

Methods

In this exploratory qualitative study, we examined new or heightened SLEs during an active phase of this outbreak. We used a list of SLEs acquired from the first phase of our study, whereby we conducted open-ended surveys and performed an in-depth focus group. We applied Lazarus and Folkman’s transactional model of stress and coping to understand diverse focus-group participants’ appraisal of events. We coded survey data and applied sentiment analysis.

Results

Participants varied in perceived threat and challenge appraisals of COVID-19, indicating both calm and fear. From 267 coded and sentiment analyzed events from survey text, 95% were predominantly negative; 112 (42%) very negative and 142 (53%) moderately negative. Social capital was unanimously emphasized upon as monumental for example: family, friends or technology mediated. We additionally identified seven major themes of SLEs due to the pandemic.

Limitations

Our sample profile is not inclusive of all subsets of the population.

Conclusions

Participants mostly shared similar frustrations and a variety of SLEs such as fear of the unknown and concern for loved ones as a result of COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus, Transactional stress model, Stressful life events, Sentiment analysis, Social capital

Highlights

-

•

The COVID-19 is adding or heightening Stressful Life Events.

-

•

People are finding active and passive ways to cope with COVID-19 SLEs.

-

•

Social Capital is monumental during crises such as a novel global pandemic.

-

•

Social distancing has strained social capital and people-coping as a resource.

1. Introduction

The Corona Virus Disease of 2019 (COVID-19) was first reported in Wuhan China in December of 2019 (WHO, 2020a). Since then, the disease has ravaged through populations worldwide paralyzing public health efforts and health systems with the continued devastating death tolls projected by the time of this publication. On March 11th, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the disease a global pandemic (WHO, 2020b) and nations all over the world called for measures to combat the disease within their own countries. As of the writing of this article, March 28th, 2020, the global count includes 571,678 confirmed cases with 26,494 deaths (WHO, 2020c). In the U.S., there have been 101,242 confirmed cases and 1588 deaths (Chavez, 2020).

Stressful life events (SLE) have been studied over tens of decades and are postulated precursors of health behaviors, outcomes and quality of life (Holmes and Rahe, 1967; Cohen et al., 2019; Dong et al., 2019; Rafanelli et al., 2005; Lillberg et al.,2003; Muscatell et al., 2009). In health psychology, the overall physical and environmental effects of stress are often studied along with mediating and moderating factors, such as coping and social support (Hobfoll, 1998; Ward et al., 2003). Social capital is the collective term for various support initiatives available to members of social groups which have been shown to provide individuals and communities resources to deal with adversities (Nakhaie and Arnold, 2010; Wind and Villalonga-Olives, 2019). Studies have long demonstrated that variations of stress-related depressive moods depend on individual satisfaction with social capital from available social support systems (Krause et al., 1989; Nakhaie and Arnold, 2010; Wind and Villalonga-Olives, 2019).

In early 2020, while the COVID-19 crisis was still in a semi-latency period, at least for the U.S., we began our initial study on stressful life events (SLEs). We aimed to investigate SLEs for different demographic groups and assess differences, if any, in how the different demographic groups experience and appraise SLEs. We were also interested in whether there were differences in social capital for different demographic groups, particularly of varying nativity and whether appraisals of SLEs would vary due to perceived social capital. To help answer this question and others we embarked on a mixed methods study that assessed the variety of stressors largely faced by people in different demographic groups in the U.S. Through this phase of our study, we hoped to create, pilot test and validate a stress rating scale that can be used to assess the onset of disease as an enhancement to what has been previously presented by Holmes and Rahe (Holmes and Rahe, 1967) with their Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS). Our intention was to develop a toolkit informed and appraised by individuals from diverse backgrounds and inclusive of modern-day stressors beyond the SRRS and its variants.

By the time we were done conducting the interviews and first surveys, the COVID-19 U.S. numbers had more than tripled with cases hitting over a hundred thousand. As we analyzed results for our ongoing study, it became clear that the pandemic, as a stressful life event, was becoming dominant. Researchers acknowledge the complexities in studying perceptions and reactions to unexpected and potentially stressful events especially where events unfolding could reveal changes in affect, cognitions and even behavior patterns (Gaspar et al., 2016). Our initial study participants underscored heightened stressful life events associated or as a result of the pandemic. We subsequently incorporated a COVID-19 based study and initiated a second guided-survey where we collected open-ended responses on COVID-19 associated or exacerbated stressors. We also conducted an in-depth focus group with a group of 15 diverse individuals from assorted professions.

2. Methods

We incorporated triangulation to investigate the element of stress from a variety of cultural groups. Triangulation involves more than one method of data collection and can help determine completeness of data and transcend limitations of individual methods (Carter et al., 2014). We conducted key informant interviews (N = 34), two open ended surveys (N = 85 and 205 respectively) and two focus groups (N = 10 and 15 respectively). We restricted participation to only eligible U.S. adult residents who were 18 years and older and were able to communicate in and read English. Interview and focus group scheduling were all done via online schedulers (www.calendly.com and www.doodle.com). Adult individuals from all races/ethnicities could participate, including undocumented U.S. residents as long as temporary status from a visa or other instrument was not an issue. We did not ask for verification or description of eligibility.

Our interviews and first survey occurred concurrently. The survey was hosted on Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and used the same questions as the interviews. We used the research crowdsourcing website, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk https://www.mturk.com), which offers research tools including an Amazon verified diverse, heterogeneous population and verifying participants using active Amazon account information. MTurk’s Human Intelligence Tasks (HITs) allow for a researcher to set requirements for subjects including demographics, country of residence and prior approval rate based on the worker’s other MTurk work. Qualified MTurk participants received information about the survey and were routed to our online survey on Qualtrics where their informed consent was requested. A total of 120 participants responded.

A focus group was scheduled after the interview and survey data were completed to dig deeper into the stressful life events by select demographics and narrow down data into themes. This first 2-h focus group with ten participants entailed an in-depth discussion about social capital and a guided session on the second half. Poll-everywhere (www.polleverywhere.com), a website that allows for live participant interaction, was used to refine our coded stressful life events towards a scale creation in our ongoing study.

Dominant themes associated with the Coronavirus pandemic were investigated further using additional open-ended Qualtrics surveys via MTurk and a second 2-h in-depth focus group. We obtained data from 220 survey respondents and 15 focus groups participants. We used NVivo professional plus software (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 12, 2018) to code all research data. The unit of analysis was the life events and stressful experiences described by participants and the social capital from person-centered coping mechanisms identified. Stressful life events (SLE) themes were coded and grouped for each demographic category. Sentiments were auto-coded for survey data and manually verified and refined on NVivo.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic variations in stressful life events

We reported data from a diverse group of individuals of varying races, ethnicity and nativity status. Table 1 illustrates the demographic breakdown of all study participants. We informally defined stressful life events as distinct non-episodic events that would cause a significant change in mood or strain routine functioning and gave two specific examples (i.e. death of a loved one and loss of employment). We asked participants to identify at least five of these events that would be significantly stressful for them if they happened and any additional ones that others who shared the same demographics (specifically race, ethnicity and nativity) would experience. We coded data from 34 interviews and 120 surveys highlighting the most dominant (top 15) stressful life events by race, ethnicity and nativity status in Table 2 . The table indicates how many code frequencies of the SLEs were recorded by participants from each demographic group. By the time we were gathering these data, the U.S. had not yet reported any cases of COVID19 so any stressors related to disease outbreaks or global pandemics ranked low, at position 28. A complete list of identified SLEs from preliminary qualitative results from our ongoing study is shared in Appendix 1.

Table 1.

Demographic breakdown of participants.

| Gender | Interviews N | Survey 1 N | Total N | Focus Group 1 N | Survey 2 N | Focus Group 2 N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 22 | 42 | 64 | 6 | 105 | 9 |

| Male | 12 | 43 | 55 | 4 | 100 | 6 |

| Age Group | ||||||

| 18-24 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 34 | 1 |

| 25-44 | 26 | 52 | 78 | 6 | 114 | 11 |

| 45-54 | 4 | 24 | 28 | 1 | 45 | 2 |

| 55-64 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 12 | 1 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Asian | 9 | 17 | 26 | 2 | 45 | 2 |

| Black | 10 | 14 | 24 | 5 | 46 | 7 |

| White | 7 | 30 | 37 | 2 | 54 | 3 |

| Latino | 8 | 17 | 25 | 1 | 59 | 2 |

| All Others | 0 | 7 | 7 | - | 1 | 1 |

| Nativity | ||||||

| U.S. Born | 11 | 58 | 69 | 4 | 106 | 5 |

| Immigrant | 18 | 8 | 26 | 4 | 71 | 7 |

| 1st generation | 5 | 19 | 24 | 2 | 42 | 3 |

| Educational Attainment | Data not collected | |||||

| Less than high school | 2 | - | ||||

| High school graduate | 50 | - | ||||

| Bachelors | 93 | - | ||||

| Graduate or higher | 60 | - | ||||

| Socioeconomic status | Data not collected | |||||

| I am unemployed, as a result, I or my family has trouble making eds meet | 23 | - | ||||

| I am employed but also qualify for or receive one or more government funded benefits such as WIC, SNAP and Medicaid | 52 | - | ||||

| I do not qualify for or receive any benefits but I or my family has difficulties making ends meet | 28 | - | ||||

| I or my family can get by with little to no problem making ends meet without added assistance; | 50 | - | ||||

| I or my family make enough with some to spare and have no problem making ends meet | 52 | - | ||||

| All participants | 34 | 85 | 119 | 10 | 205 | 15 |

Table 2.

Top 15 stressors by race and ethnicity and US nativity status.

| Asian | Black or African American | Latino | White | US Born | 1st Generation | Immigrant | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Death of a loved one | 90 | 90 | 90 | 95 | 95 | 90 | 92 |

| 2 | Racism | 82 | 97 | 89 | 0 | 22 | 67 | 97 |

| 3 | Discrimination includes implicit bias and stereotyping | 83 | 92 | 89 | 12 | 48 | 67 | 92 |

| 4 | Personal health issues | 47 | 44 | 38 | 97 | 73 | 77 | 89 |

| 5 | Financial hardship and economic crisis | 77 | 80 | 83 | 76 | 74 | 80 | 44 |

| 6 | Loved one’s health issues | 75 | 60 | 59 | 90 | 70 | 75 | 60 |

| 7 | Unemployment, loss of job or means of livelihood | 49 | 73 | 72 | 44 | 44 | 49 | 73 |

| 8 | Poverty, minimum wages and inadequate basic needs | 40 | 70 | 71 | 24 | 24 | 40 | 75 |

| 9 | Parenting challenges | 22 | 12 | 9 | 47 | 50 | 24 | 67 |

| 10 | Work related challenges and stresses | 20 | 25 | 55 | 63 | 63 | 35 | 54 |

| 11 | Debt | 74 | 80 | 72 | 89 | 89 | 74 | 80 |

| 12 | Acculturation and assimilation challenges conflicts | 49 | 33 | 59 | 5 | 5 | 60 | 80 |

| 13 | Job-seeking and lack of jobs or career growth | 24 | 72 | 74 | 40 | 26 | 24 | 72 |

| 14 | Loneliness, Isolation including separation from family | 20 | 20 | 39 | 7 | 7 | 20 | 85 |

| 15 | Immigration challenges including fear of deportation and loss of status | 22 | 35 | 77 | 0 | 11 | 22 | 75 |

Appendix 1.

Full List of Coded SLEs.

| Rank by coding frequency | Description of SLE |

|---|---|

| 1 | Death of a loved one |

| 2 | Racism |

| 3 | Discrimination includes implicit bias and stereotyping |

| 4 | Financial hardship and economic crisis |

| 5 | Personal health issues |

| 6 | Loved one’s health issues |

| 7 | Unemployment, loss of job or means of livelihood |

| 8 | Poverty, minimum wages and inadequate basic needs |

| 9 | Parenting challenges |

| 10 | Work related challenges and stresses |

| Debt | |

| 12 | Acculturation and assimilation challenges conflicts |

| 13 | Job seeking and lack of jobs or career growth |

| Loneliness, Isolation including separation from family | |

| Immigration challenges including fear of deportation and loss of status | |

| 16 | Divorce or separation from significant |

| 17 | Eviction, foreclosure, loss of housing and homelessness |

| 18 | Educational challenges including cost |

| Hardly any (unique) struggles | |

| 20 | Harsh (current) political climate |

| Marriage and issues with significant others | |

| Mental health issues including clinical diagnoses | |

| 23 | Family problems and conflict |

| Internal conflicts | |

| 25 | Chronic or prolonged illnesses or terminal disease and associated challenges |

| Relocation | |

| Aging challenges | |

| 28 | Experiencing or recovering from major disease outbreaks or natural disasters including severely inclement weather |

| 29 | Accidents and injury including car accident |

| Cultural and ethnic obligations, woes or disappointment | |

| Family or loved one in distress | |

| Health insurance, lack of it, cost or loss | |

| Navigating systems, particularly government | |

| Transportation issues including car breaking down | |

| Childcare difficulties including cost | |

| 36 | Assortment of hate crimes |

| 32 | Housing instability, cost and challenges |

| One’s children in distress | |

| Saving for the future and retirement | |

| Unsafe or low-quality environment and neighborhoods | |

| Being undocumented in the US and the uncertainty | |

| 42 | Environmental nuisances and discomfort |

| Legal issues | |

| Poor or low access to amenities including health, education, environment | |

| Unexpected major financial obligations | |

| 46 | Burden of caring for sick or old family members |

| Death of a pet | |

| Disaster in home country | |

| Family expectations and obligations financially and or culturally | |

| Fear of mistreatment by law enforcement | |

| Having and recovery from major health procedures | |

| Major home repairs | |

| Mortgage, rent and cost of housing challenges | |

| Reverse racism or discrimination | |

| 55 | Aging or sick family in home country |

| Being in or experiencing war or combat | |

| Being the victim of a crime | |

| Conflict with close friends or loved ones | |

| Dealing with costly medical procedures or needs | |

| Disability | |

| Domestic or other violence | |

| Experience or encounter of police brutality or partiality | |

| Helplessness when witnessing injustice | |

| Pregnancy and newborns | |

| Substance misuse and addiction | |

| Work life imbalance | |

| 67 | Betrayal by family or loved one |

| Exhaustion and sleep deprivation | |

| Food deserts and food insecurity | |

| Miscarriages | |

| Political instability or war in home country | |

| Social interactions or obligations | |

| Violence including domestic | |

| 74 | Childhood trauma |

| Religious woes | |

| Xenophobia | |

| Some SLEs were tied: had the same number of codes as referenced by participants in their open-ended text | |

3.2. Sentiment analysis of text relevant to coronavirus

We asked participants to highlight any new stressors or exacerbated existing stressful life events due to the current pandemic and describe them in detail. Qualtrics validation was applied so that this was a required question on the survey. Out of 299 responses, 205 were deemed useable and were coded in NVivo. The software identified positive and negative sentiments in a high (very) and moderate extreme. Text analysis on software like NVivo is limited and does not fully analyze sentiment or recognize contextual phrases associated with some sentiment like sarcasm, slang or ambiguity. We thus manually refined these and coded overarching SLE themes. Ninety five percent of the 267 unique coded sentiments were predominantly negative for SLEs, with 112 (42%) ‘very negative’ and 142 (53%) ‘moderately negative’. We classified ‘very negative’ stressors as those actually experienced by participants, for instance loss of a job or lack of amenities. ‘Moderately negative’ stressors had mostly to do with fears and worry, for example the indication of uncertainty. Positive themes included entries of readjustments of life that didn’t show indication of stress or strain, for example, “I work from home now”. A few entries explicitly stated they had no COVID-19 related stressors and were thus coded into ‘very positive’. Table 3 highlights a few examples of survey entries coded at each sentiment.

Table 3.

Sentiment analysis of SLE text related to Coronavirus.

| Very negative |

Moderately negative |

Moderately positive |

Very positive |

|---|---|---|---|

| 112 (42%) | 142 (53%) | 2 (3%) | 10 (2%) |

| Having to stay inside a lot is causing lots of loneliness and mental health issues like anxiety, and dealing with a toddler all day is maddening. The other person in my home is not able to work as much so our finances are getting tighter and the stores are low on food that we need so it is making it stressful in that area as well. I’m unable to connect with friends in person and feel more isolated. Income reduced, no immediate family in this country fir support. Both work in medical field offering direct care to pt, daily potential exposure to covid victims. Anxiety due to daily challenges and changes with PPEs scare, lack of emotional support, psychological support. anxiety since all family live away from us, incase of anything we cannot even travel. Saving is currently a challenge since we have to support family back at home. Budget is tight. There is a huge spike of racism against my family and my people ever since the COVID-19 epidemic breaks out in the U.S. This makes me not only worry about my family’s safety because of the possibility of contracting the virus, but also from the racists who are looking for an excuse to attack and terrorize Asian American families. Covid 19 has been me lonely because I have to stay at home.It has also made work very stressful and demanding I recently moved to a new town and was relying on my freelance work in the events industry to survive until I found a job in my new town, but the entire industry has been cancelled and I’m out of my usual way of making money. Jobs that are still available are hard to get because it’s so competitive since a lot of people are unemployed. I don’t have a home yet, it’s hard to get one without a job so I am facing homelessness. I’m currently working and earning much less which makes me stress about meeting my family’s financial obligations. I also don’t know when I can travel overseas to see my parents or help them in any way. I have lost my job, filed for unemployment, have 0.00 and unemployment is backed up so no money has been sent. We are unsure when we will start receiving monies so likely will need to move since we cannot pay rent Having to stay inside a lot is causing lots of loneliness and mental health issues like anxiety, and dealing with a toddler all day is maddening. I have lost both my jobs related to the virus I lost my job because of COVID-19 (at a restaurant), which was the highest paying job I have ever had, and this has had a ripple effect on the rest of my life. I am very worried and stressed about finding a new job, especially with the state of things right now, and my bills are all due as it is the end of the month. The primary household owner in my family was laid off. That has increased my stress. A stranger shouted racial slurs at me outside wwalmart and said cchinese [sic]virus. My fishes died when I could not come back from Italy on time I feel like killing myself this COVID is causing problems un able to pay my car payment and car insurance so imleft [sic] with no transportation COVID-19 is making my mental health worse because I am experiencing anxiety now. I experienced a little racism due to the Coronavirus, because of my complexion and looks. The individual that called me a racial slur thought I was from China and was the main cause of the Coronavirus. For that, I would say that is pure ignorance. Increased drug abuse |

The uncertainty of the situation freaks me out It’s hard to get food these days, even delivery Illness puts me at increased risk of severe disease if I contract the virus Covid-19 is effecting [sic] the health of my family members, it makes me stressed out and worried for them. I’m also worried about my job security as the economy continues to tank. No job would add additional stress on me because of financial issues. It’s risky to do anything where you have to leave the security of your home, and possibly expose yourself to COVID-19. You can’t go to work, or do things like go to a grocery store in peace. Medical and dental appointments must be postponed. Things you normally do in a usual day can not be done. There is a lot of injustice in how COVID tests are being distributed and made available. It is taxing on people with very little health insurance (or none). Social distancing is affecting my free movement, no more sight seeing, no more hanging out with my loved ones. The preexisting stress is now compounded because of self isolation that is in place. I keep thinking that Ican [sic] be infected any time walking in the street or working My daily life has totally changed Iam [sic] scared to go out I feel disconnected with others I have tried to order online which is more expensive and backed up. Still cannot find toilet paper or dish soap or tylonol [sic]. Ugh. Hoarding of products and not being able to find in stores Illness puts me at increased risk of severe disease if I contract the virus I worry about my retirement disappearing because of the stock market instability I fear this virus also has become a political gain for some politicians. I am just ready for it to be over so that things can get back to normal. Everyone is stock piling now so it makes it stressful to lay hands on what I want easily My wife has to go to work. She is concerned about her health because she has asthma. |

My employment [sic]is still open but is very different than normal because of people staying home Although it is an unknown or stressful time I can honestly do nothing about it an it’s no ones [sic]fault so what can we do but have a positive attitude and make have a positive attitude. Don’t be stressed and just live. |

I have no additional stress due to COVID-19 at all I don’t have any stressors from COVID 19 Not stressed working from home I feel like I can feel productive. NONE It’s not affecting [sic] me No new stressors nothing due to COVID |

3.3. Transactional model of stress and coping with COVID 19

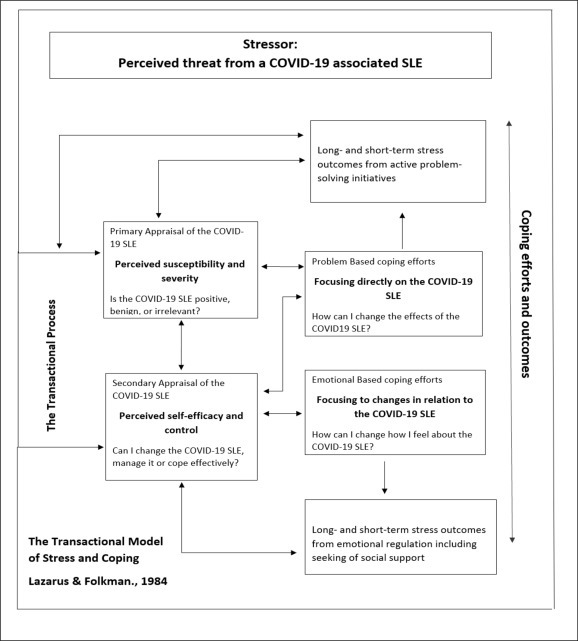

Stress viewed within a transactional model was introduced in 1984 by Lazarus and Folkman (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984) where an individual’s level of stress at a given time depends on the dynamic transaction between the individual and his/her environment. Stress levels were determined from the net transactional effect between personal and environmental SLEs and available resources such as coping mechanism. Lazarus and Folkman (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984) described cognitive appraisal as an evaluation of the stress effect to an individual. As a result of the appraisal, an event was categorized as irrelevant, benign, or a threat currently or potentially harmful. Cognitive appraisal was further subdivided into primary and secondary appraisal where primary appraisal considers encounters with the SLE while secondary appraisal evaluates available mediators and their efficacy in reducing the harm. Coping was either problem focused, actively tackling the SLE, or emotional passively addressing the stressor by focusing on reducing effects of the SLE.

Our focus group was conducted with participants who represented different professional industries. A few were parents and most were still working either on the front line in healthcare or telecommuting in light of the pandemic. We used the same semi-structured questions inquiring about new or currently increased stressors due to the Coronavirus and had an open discussion where follow-up questions were based on participant responses. Fig. 1 shows Folkman and Lazarus’ model of stress and coping applied to our study and Table 3 includes select excerpts obtained from the 15-participant focus group.

Fig. 1.

Appraising and coping with COVID-19 SLEs. Model adaptation.

About half of focus group participants indicated an ability to cope or just experience calmness from a cognitive appraisal of their threat and challenges supporting the theory that threat and challenge are not mutually exclusive (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). Responses highlighted support of the theory that coping serves either to regulate the emotions and distresses from the SLE (emotion-focused coping) or to manage the problem by directly tackling the element influencing the SLE (problem-focused coping). Participants appraise their new or heightened COVID-19 based SLE challenges as either threatening or non-threatening, and secondarily in terms of whether they had the resources to respond to or cope effectively. Participants reported making significant physical and psychological alterations in order to cope with the imminent threat, such as shutting off all news, incorporating new hobbies or adopting faith and spirituality. This was consistent with the “threat or harm” approach (Cohen et al., 2019) that significantly alters routine activities or status and poses a threat to available resources (Lazarus, 1974). If the perception is that there is a lacking capacity to respond to the challenge, the individual would most likely to lean on emotion-focused coping responses such as wishful thinking (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984).

Focus group participants acknowledged there were unknown variables towards problem-focused COVID-19 coping by considering things were ‘out of their control’ and they could not possibly do anything else beyond the measures they already had in place. Coping strategies varied from positive thinking to denial and/or optimism. All participants acknowledged their environmental influences, appraised their coping resources and ended up on opposite ends of the ‘current or projected mental state’ curve as shown in the examples highlighted on ‘stress outcome’ in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Applying the Transactional Stress and Coping Model to Focus Group Participants’ responses.

| Potential Stressor | Primary Appraisal “Am I OK or in trouble" |

Secondary Appraisal and Evaluation “What can I do about it" |

Coping Strategies Passive and Active |

Stress Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

COVID-19 and associated stressors e.g. health, financial, isolation, the unknown |

Calm but there’s a little worry in the back of my mind Panic and fear of the unknown, Scared for my elderly parents. I know if my mom who has health issues gets the covid19 she won’t survive it. I don’t know whether I’m overreacting I am used to working from home, so its relatively the same as normal life … But I can’t shake this feeling in my chest …. , you know, is this a COVID symptom or is this just a lot of anxiety- this tightness in my chest |

Stressing out doesn’t help me out one bit so I’m trying to remain calm and do what I need to do to disengage when necessary. I was reminded my job right now is to keep her safe and make her feel that she is safe and everything else is secondary So I feel like I don’t even have time to process what’s going on a lot of the times it’s just a lot of putting out fires |

Currently stable. Learning ways to keep my mind busy A lot of people will ask why I’m so quiet and it’s ‘cause I need to distance myself from the news for a bit. Stressing out doesn’t help me out one bit so I’m trying to remain calm and do what I need to do to disengage when necessary I’m generally doing well but I just realized recently that I’m in the self-preservation mode where I am avoiding the news coz I don’t want to get fearful. I think for my own good I just don’t want to think a lot about what’s going on around the world. |

Not good. Too much anxiety. I have PTSD and agoraphobia and that doesn’t bode well right now. And so I try to reflect on that and think about that too as I’m going through this but it’s not helping with my own personal mental health in my own fear I’m not as stressed as I should … I cannot do anything beyond what I’m already doing to keep myself my family safe and it’s out of my control I’m not as stressed as I thought I would be although the stress increases as time goes on and more people are diagnosed especially closer and closer to me. I am stressed out and it does impact her (daughter) |

| Coping resources | Physical | Material | Social | Psychological |

| I do reflect on my privilege … I’ve been organizing mutual aid drives for folk …. that gives me a sense of pride and destresses me … Online Yoga and working out in the park I just shut off every electronic in my house for two days and just had a meditation and that kind of helped Catching up on sleep and spending time growing my faith My hands are completely dry and cracked from washing and bleaching and sanitizing ….and that’s how I can exercise control |

Sometimes I can turn it off and I watch Real Housewives of Atlanta and kind of laugh … I’ve been reading books Eating a lot … A lot of drinking and sulking … |

Being informed is one thing but being inundated with all the bad news isn’t helpful. The memes are fun though. I’ve been finding myself going for walks, like multiple times a day and smiling at everybody. I see on the street just because I’m hoping it’s some kind of like human interaction.” |

Stressed and worried but I put on a professional calm mask in order to not cause panic. I think it’s just to take it day by day as opposed to thinking about. What is the next week going to bring? What’s the next month going to bring? What’s the next year going to bring because I feel like that’s really beyond my control and beyond anyone’s knowledge or awareness That’s why I’m so calm, you know for me. I’m the kind of person who I’m like if I can’t control it then, you know, you know, I don’t worry about it. |

3.4. Overarching themes of coronavirus related stressful life events

From survey data and focus group sentiments, we identified five major themes from the current pandemic: (a) financial constraints, (b) isolation from family, (c) dwindling mental health, uncertainty, (4) worry about the future and (5) work-related challenges. Demographic differences from the survey are shared where applicable. Select excerpts are shared as spoken by focus group participants (FGP) with code names used. We omitted any reference to people such as celebrities or politicians and political parties.

3.4.1. Financial constraints and loss of employment

An assortment of financial challenges was identified as the dominant stressor during the pandemic. Survey participants indicated job loss, lost hours and other pressures from bills. We did not notice any demographic specific differences other than by educational attainment and socioeconomic status. Participants who particularly relied on or were qualified for government assistance indicated financial struggles and fears such as how they would pay for essentials and medical care. Slightly more participants below a bachelor’s degree attainment (36%) indicated new or increased financial stressors compared to 20% of those with bachelor’s degrees and higher. Participants from higher-ranking socioeconomic categories (can make do without government assistance or can make do with plenty to spare) largely described financial uncertainty for the future including downturns in their retirement, stock and savings accounts as a result of the pandemic. No personal financial concerns were discussed by the focus group, but participants did share professional experiences and concerns particularly those in community-based professions including public health working with disadvantaged communities.

3.4.2. Dwindling mental health

Poor mental health was noted across demographics with a few noticeable intensities. More males than females indicated mental illness, albeit without further description as a stressor, caused by the pandemic. Increased substance use, (e.g. alcohol and tobacco), also accompanied entries of reduced mental health for males. Females, however, elaborated on stressful life events they were experiencing, such as job loss due to being in the hospitality or food industry, highlighting potential underlying mental dysregulations. Females in the study also reported multiple stressors as a result of the pandemic compared to fewer responses from males.

FGP: Echo:Yes, I am stressed out actually last week. I was having panic attacks.

3.4.3. Isolation and loneliness

Isolation was an overarching theme with most demographic groups sharing the same sentiment. Immigrants particularly had a lot to share as their isolation included sentiments of being away from their families in their home countries.

FGP Yucca:I’ve been living by myself for the last couple years … most of my peers are married or have children or other responsibilities, …but I so need to be socially connected to so, you know, I do see that my social media using has increased significantly.

3.5. Misinformation and fear of the unknown

No major patterns were observed when this theme was analyzed by demographics as fear was almost equally reported. Younger participants (under 45 years old) however shared more context.

FGP X:But the problem is you’re not getting proper information from anywhere the news or the media …. You don’t know what’s actually out there and first they say “we already know this is an RNA virus”. Then they say “it’s more like the flu”, but now we just learned or they’re telling us that it can actually last for 24 hours outside the host and stable which is very rare for an RNA virus.

FGP Silver:So, I follow a lot what’s going on in Europe and especially Latin America … Some of them goes aligned with the rest of the world and some of them are not … It’s quite puzzling here. For some reason, they think that this is going to be done in two weeks for some odd reason.

FGP: Bila Shaka:I see misinformation everywhere … … trying to pass Green New Deal with the stimulus package to using Chloroquine to prevent corona … I worry about people believing some of the nonsense.

FGP: Ruth:I think I’ve had conversations with a couple of people, and everybody is sort of the armchair virologist geneticist. … how this started, why this started, why it’s so big in Italy why it’s big here. I just think nobody knows no not even the experts not even the virologists. Not even the infectious disease specialist. … so much of it is speculation you hear one day it only lasts on surfaces for 24 hours. You hear the next day it lasts on surfaces for five days, and I just think there’s too much uncertainty right now.

3.6. Xenophobia and racism

A significant theme of racism and xenophobia was reported by race. Asian participants highlighted acts of hate perpetrated upon them and others due to Coronavirus, which other races resonated with, based on past similar event.

FGP Unicorn:I identify as Asian Pacific Islander person … whenever we talk about a disease or a virus coming from a specific area and it and if it’s from somewhere not in Western European areas people tend to become extremely racist towards that community and so since the virus came from Wuhan China, now Chinese folks but not even just Chinese folk anyone that’s Asian is being targeted … Not that it’s just discrimination, but it’s now leading to actual violence ….

FGP: Tiffany: … he [President Trump] says it’s a Chinese virus or whatever, but everybody knows that he’s talking about all Asians … And I feel like this country is pretty much born on fear on stirring up that type of fear and that type of hatred and it just bounces around from community to community.

FGP Jo:And everything I mean and I understand the xenophobia because I remember like when Ebola was a big thing … it’s a sad but it’s a reality that I think that people you know who look like me or not from where I’m from have experience for so long. It’s almost like second nature like we’re so used to it. But you know, I can sympathize with you know, with all the Asians and Asian-Americans and everybody that’s going through it now because that’s how we felt for a very long time and continue to feel.

3.6.1. Work related and associated challenges

Focus group participants represented diverse industries (Appendix 2) including education, health and healthcare. None of them indicated loss of employment except for the substitute teacher who was also a graduate student. Frustrations shared were based on professional experiences and readjustment. For instance, professors having to transition to an online format, or public health practitioners sharing frustrations and challenges experienced or on behalf of those they serve. Examples shared include lack of COVID-19 tests and personal protective equipment, economic effects of the pandemic on disparate communities and increased workloads.

FGP Titi:I typically work from home but having my daughter with me at home that’s a stressor coz I still do have a full workload and my daughter’s only about 15 months old and she wants my attention and I still have some work to get done.

FGP Panda: …. like in public health, we work with so many families that are already kind of living on the Edge, you know and all that it takes is one little push over the edge for them to have something go wrong and the disparities to really, you know, just blow out of the water.

FGP JJ:Because of the coronavirus I just have so much more free time now

FGP Baraka:I’ve lost my sense of purpose because I’m so used to getting up every morning and going to school and I am teaching online and everything has transitioned to online but it doesn’t feel the same. It just feels like the distance between me and my students

Appendix 2.

Focus Group Participants by Profession.

|

3.6.2. Concern for loved ones

This was a dominant theme particularly among female participants who indicated they were parents concerned about their children; 6 females vs. only one male. Highlights of such concern included homeschooling challenges. Immigrant survey and focus group participants particularly indicated concerns for older parents and relatives (particularly relatives) who have family in their home countries.

FGP D-Wiz: … because in Africa, what’s gonna happen to them if this virus gets to them because the medical situation is completely different from American, you know, hospitals and medical facilities.

FGP Panda:It’s really hard, … that fear of the unknown and I don’t know how I would handle the stress if one of my family members came down with it.

FGP Echo: I’m worrying about my parents who you know, they are sickly and I’m like if they get this disease, they won’t survive it. It and if they don’t survive it, I won’t be able to go to their funeral because there’s no plane to take me there.

3.7. Social capital at a time of social distancing

Adequate social support alleviates the etiology of mental disorders and can moderate ensuing depression. Social isolation is a mental health determinant exhibited along racial and ethnic lines, and might be worse for some demographic groups such as immigrants (Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012). Survey sentiment analysis on social support was entirely positive (96%) with a few neutral stances; for instance, a participant stated: They are helpful but not needed at the time when everyone is facing the same problem as I.

Focus group participants emphasized support systems including religious and community helping them cope. Others accentuated stresses from not being close or having to social distance themselves from their support systems. Technology mediated social support was a dominant emerging social capital theme. Participants shared anecdotes of virtual playdates for children and informal meetings such as happy hour with friends. All participants indicated amplified use of phones, messaging apps and social media to keep in touch with family, friends, coworkers and others in the community. Excerpts from focus group participants (FGP) and survey participants (SP) on social capital are shared below

FGP Tito: It’s starting to wear on me because I feel like I am getting trapped in my own house, and it’s not I’m not even so concerned about the whole aspect of society falling apart so much. I’m just kind of feeling a little claustrophobic in my own house. I’ve been finding myself going for walks, like multiple times a day and smiling at everybody I see on the street just because I’m hoping it’s some kind of like human interaction.

SP 1:I like to be out and about, being in a home alone with no one around me is hard to cope with at time.

FGP Baraka:… being able to lean into my church community my small group and to spend more time with God. So, I’m really grateful for that.

SP 2:My family, friends, and loved ones have been my rock. I don’t know if I’d be able to handle this alone.

SP 3:We talk about it. We reassure each other that everything is going to be ok.

SP 4:My immediate family is safe together, we can have social distancing get-togethers with neighbors outside, friends and extended family can keep in touch by phone.

FGP: Giraffe:I’m working from home on telework I’m able to as I walk around and meet my neighbors and you can sort of you can feel their fears as you talk to them. And you get to know the names of their dogs …, you can to see that they’re kind of afraid about the unknown and I’m able to leverage what I know to kind of calm their nerves a little bit and let them know that this too shall pass …

4. Discussion

With news and current events dominated by COVID-19 related stories, we had limited challenges meeting our sample quotas. Open-ended online surveys were adequately responded to. Demographic-specific disparities were seldom reported except on xenophobic and racist events surrounding Asian individuals as described by both survey and focus group participants. Our observation matches recent reports highlighting a backlash of discrimination and xenophobia against Asian Americans (Reny and Barreto, 2020). The backlash is comparable to those during the SARS outbreak in 2003 (Person et al., 2004), H1N1 in 2009 (Sparke and Anguelov, 2012), and Ebola in 2014–2016 (Kim et al., 2016) where communities are vilified leading to racialized behavior such as avoidance and bullying (Reny and Barreto, 2020). The use of technology has reportedly skyrocketed with cell phones, messaging apps, web conferencing technologies (e.g. Zoom and Skype), email and social media being the main avenue that the majority of the population can keep in touch with their friends, families, and loved ones or keep up with the news. Furthermore, because of advances in technology, participants described fewer disruptions to their daily routine due to ability to work from home or attend classes online. It was additionally clear that everyone felt it necessary to be informed yet struggled with the changing and overload of COVID-19 related news and guidelines.

To our knowledge, previous studies have not examined the association of social capital and stressful life events during a global scale pandemic. Results from our study highlight that greater social support is indeed associated with lower perceived stress during the early phase of the COVID19 pandemic. Our study participants who were parents of young kids emphasized challenges of homeschooling their children but reiterated during focus groups that it was more important to create a calm environment with a redefined normalcy for growing children whose future could very well be shaped by this crisis. One focus group participant highlighted that her child’s school organized a weekly online class session via Zoom for students during the school closure and even had loaner electronic devices for children in need. Additionally, focus group participants appreciated the opportunity to vent and share some fears and frustrations in a group setting, some reiterating that the session has been the most human communication they have had outside their work and family in while.

On coping, participants differed in their emotion vs. problem focused coping based on their appraisal of the COVID-19 threat and its current or potential challenges. Social capital, operationalized as social support is positively associated with health outcomes in the population and can provide resources to deal with adversities (Wind and Villalonga-Olives, 2019) such as those related to COVID-19. Due to the unprecedented nature of the current pandemic, research is lacking that would highlight the benefits of social capital in an era where distancing is encouraged to save lives. Nonetheless, previous studies have highlighted improved health outcomes from impacted health behaviors and influenced psychosocial processes due to connectedness (Kawachi et al., 2008; Nieminen et al.2013). Kawachi specifically highlights lower levels of social trust associated with major causes of death particularly from chronic diseases such as heart diseases and cancer. The widespread disparities in health among racial, ethnic and socioeconomic groups particularly during emerging epidemics have been described in the literature (Des Jarlais et al., 2005). Additionally, highlighted in the literature is the stress of contracting a disease due to worry and lack of information (Nieminen et al.2013), a concept we also observed in the early phase of the pandemic. Our focus group purposely deviated from a discussion of a political nature. Nonetheless, the rhetoric of uncertainty in communication especially from political leaders was not absent. Historical evidence regarding epidemics suggests that it is impossible to disentangle such events from the politics (Ebook central, 1024).

Social capital can improve health outcomes by influencing access to health services and amenities, impacting health-related behaviors, and affecting individual psychosocial processes (Xu et al., 2020). Participants particularly emphasized perceived dire effects if they were devoid of any form of social capital. Their family, friends, coworkers, religious and community associates or even social media comrades helped cope, share news and tips or just divert their attention from the current world-wide chaos. Despite the coping strategies discussed, the novelty of the pandemic and current events had participants leaning on multiple coping methods. The general scheme of social capital discussion was that both sets of participants either longed for interactions, held on to connections, or invented new ways to interact and maintain or enhance social capital. This concept is in accordance with Wind and Villalonga-Olives (Wind and Villalonga-Olives, 2019) who describe a manipulation that consists of activities that directly build or strengthen social capital when social capital is the intervention target. Snowden particularly discusses pandemic situations, and the effectiveness of quarantines (Ebook central, 1024) which would add value to future similar studies that investigate coping during social distancing and whether the enhanced survival is perceived as a worthy tradeoff from the lack of connectedness.

A nascent concept towards the end of the group session touched on the aftermath of the pandemic; those who had lost loved ones, those who had been without or emerge from the pandemic without social capital and those with various forms of trauma due to the pandemic. In summary, the more pragmatic and objective problem based coping efforts (see Fig. 1) was more pronounced in participants during this early pandemic phase. Participants efforts were more directed at defining the problem and finding solutions, which included enhancing their social capital. The protective effect of social capital on stress warrants further exploration. As the COVID-19 upheaval continues to unfold and the unknown evolves into fruition, it is clear that SLEs, having the potential to impact health and wellbeing, will continue to be experienced or exacerbated for most people.

5. Limitations

Due to the novel COVID-19 being a new pandemic currently ongoing as of the writing of this article, this study could present some gaps in stressful life events as the situation unfolds. Because of the caliber of its global effect, there seems to be a lot of uncertainty about the future which in itself is a huge stressor for most. People from different demographic groups could exhibit renewed or increased devastations as the ravaging effects of the disease continue. Only two out of 205 survey participants indicated educational levels lower than a high school diploma and all focus group participants were professionals with at least a bachelor’s degree. Efforts to sample other minority groups proved futile with no American Indian and Pacific Islanders responding to the survey HITs. Additionally, those without computers or with lower literacy levels may not have been able to access the survey or focus group scheduling. As a result, experiences and perceptions of a subset of the population is lacking.

6. Conclusion

Our study highlights the broader effects of the pandemic. In the U.S. with exceptions by demographics, financial strains, racism and isolation increased due to reduced travel to home countries of immigrants. At the preparation of this manuscript, (April 2020), the pandemic has not been controlled and various cities in the U.S. were on recommended or mandatory lockdown with all K-12 schools closed, most public universities transitioned to online and workers either temporarily displaced, telecommuting or deemed ‘essential and are reporting to work’. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore stressful life events during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated social capital in terms of coping. Our findings suggest that as part of public health preparedness and health promotion, policies should be explored that fund increased social capital such as online religious events and district-wide K-12 class sessions via video hosting capabilities such as Zoom. Ultimately, social capital can effectively lower stress which can decrease the health and quality of life associated outcomes from unexpected or unavoidable stressful life events such as those from a global pandemic like COVID-19.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has recently stated that the effects of the coronavirus pandemic would be imprinted on the personality of the country for years to come, stating “I think there’s going to be some subliminal post-traumatic stress syndrome that we’re all going to face” (Forgey, 2020). Future studies and health promotion efforts should address each stressor independently, particularly those who were already living on the edge before COVID-19 emotionally, socially or even financially.

7. Human participation protection

This study was approved by Loma Linda University Institutional Review Board. All study participants provided informed consent and had the option to decline or withdraw from participation at any time. No identifying information was requested. Anonymity was maintained through coded names for interview or focus group participation. Web-based survey did not query for any identifying information, and participants were reminded to maintain their anonymity. Unexpected interview personal identifiers were anonymized in the analytical datafile to prevent participants from being identified from any sensitive information that may have been inadvertently shared. All eligible participants equally participated in all aspects of the study selected. Completed transcripts have no personal identifiers. The Internet Protocol (IP) address collection feature was disabled on Qualtrics. All research information including interview recordings is stored in password protected shared folder hosted on a cloud-based portal only accessible to the study team.

Role of the funding source

This research was funded, in part, by a doctoral dissertation stipend to the first author from the Loma Linda University, School of Public Health.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Cindy Ogolla Jean-Baptiste: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, preparation. R. Patti Herring: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. W. Lawrence Beeson: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Hildemar Dos Santos: Writing - review & editing. Jim E. Banta: Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants who took part in the interviews, focus group and those from MTurk who responded to the open-ended survey.

References

- Carter N. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2014;41(5):545–547. doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.545-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez N. CNN; 2020. US coronavirus cases reach more than 101,000 as reported deaths hit new daily high.https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/27/health/us-coronavirus-friday/index.html [cited 2020 03,28,2020]; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Murphy M.L.M., Prather A.A. Ten surprising facts about stressful life events and disease risk. Annual Review of Psychology. 2019;70:577–597. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais D.C. Social factors associated with AIDS and SARS. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11(11):1767–1769. doi: 10.3201/eid1111.050424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y. Stressful life events moderate the relationship between changes in symptom severity and health-related quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2019;54(5):445–451. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebook central https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/oxford/detail.action?docID=5910244

- Forgey Q. POLITICO; 2020. Coronavirus will be ‘imprinted on the personality of our nation for a very long time,’ Fauci warns.https://www.politico.com/news/2020/04/01/anthony-fauci-coronavirus-pandemic-159158 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar R. Beyond positive or negative: Qualitative sentiment analysis of social media reactions to unexpected stressful events. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;56:179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll S.E. Plenum Press; New York: 1998. Stress, culture, and community : The psychology and philosophy of stress. The plenum series on stress and coping; p. 296. xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes T.H., Rahe R.H. The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1967;11(2):213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I., Subramanian S.V., Kim D. Springer; New York ; London: 2008. Social capital and health; p. 291. x. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.S., Sherman D.K., Updegraff J.A. Fear of Ebola: The influence of collectivism on xenophobic threat responses. Psychological Sciences. 2016;27(7):935–944. doi: 10.1177/0956797616642596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N., Liang J., Yatomi N. Satisfaction with social support and depressive symptoms: A panel analysis. Psychology and Aging. 1989;4(1):88–97. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.4.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R.S. Psychological stress and coping in adaptation and illness. International Psychiatry in Medicine. 1974;5(4):321–333. doi: 10.2190/T43T-84P3-QDUR-7RTP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R.S., Folkman S. Springer Pub. Co; New York: 1984. Stress, appraisal, and coping; p. 445. xiii. [Google Scholar]

- Lillberg K. Stressful life events and risk of breast cancer in 10,808 women: A cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157(5):415–423. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscatell K.A. Stressful life events, chronic difficulties, and the symptoms of clinical depression. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2009;197(3):154–160. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318199f77b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakhaie R., Arnold R. A four year (1996-2000) analysis of social capital and health status of Canadians: The difference that love makes. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;71(5):1037–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieminen T. Social capital, health behaviours and health: A population-based associational study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:613. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Person B. Fear and stigma: The epidemic within the SARS outbreak. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10(2):358–363. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafanelli C. Stressful life events, depression and demoralization as risk factors for acute coronary heart disease. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2005;74(3):179–184. doi: 10.1159/000084003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reny T.T., Barreto M.A. Politics, Groups, and Identities; 2020. Xenophobia in the time of pandemic: Othering, anti-Asian attitudes, and COVID-19; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sparke M., Anguelov D. H1N1, globalization and the epidemiology of inequality. Health & Place. 2012;18(4):726–736. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes E.A., Miranda P.Y., Abdulrahim S. More than culture: Structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;75(12):2099–2106. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward A.M., Jones A., Phillips D.I. Stress, disease and ’joined-up’ science. Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 2003;96(7):463–464. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcg084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO WHO statement regarding cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China. 2020. https://www.who.int/china/news/detail/09-01-2020-who-statement-regarding-cluster-of-pneumonia-cases-in-wuhan-china Available from:

- WHO WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 Available from:

- WHO Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report - 68. 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200328-sitrep-68-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=384bc74c_2 Available from:

- Wind T.R., Villalonga-Olives E. Social capital interventions in public health: Moving towards why social capital matters for health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2019;212:203–218. doi: 10.1136/jech-2018-211576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Lizheng, Guo Min, Nicholas Stephen, Sun Long, Yang Fan, Wang Jian. Disease causing poverty: Adapting the onyx and bullen social capital measurement tool for China. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8163-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]