Highlights

-

•

Quality of media reporting of celebrity suicide on online media in India is poor.

-

•

About 85.5% of them violated at least one WHO media reporting guideline.

-

•

Online search interest for suicide-seeking keywords increased immediately after the reference celebrity suicide, suggestive of the Werther effect.

-

•

This is possibly associated with poor quality of media reporting of celebrity suicide.

-

•

There is an urgent need for taking steps to improve the quality of media reporting of suicide in India.

Keywords: Celebrity suicide, Media reporting, Werther effect, India, Google trends

Abstract

The literature reports increased suicide rates among general population in the weeks following the celebrity suicide, known as the Werther effect. The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed guidelines for responsible media reporting of suicide. The present study aimed to assess the quality of online media reporting of a recent celebrity suicide in India and its impact on the online suicide related search behaviour of the population. A total of 200 online media reports about Sushant Singh Rajput’s suicide published between 14th to 20th June 2020 were assessed for quality of reporting following the checklist prepared using the WHO guidelines. Further, we examined the change in online suicide-seeking and help-seeking search behaviour of the population following celebrity suicide for the month of June using selected keywords. In terms of potentially harmful media reportage, 85.5 % of online reports violated at least one WHO media reporting guideline. In terms of potentially helpful media reportage, only 13 % articles provided information about where to seek help for suicidal thoughts or ideation. There was a significant increase in online suicide-seeking (U = 0.5, p < 0.05) and help-seeking (U = 6.5, p < 0.05) behaviour after the reference event, when compared to baseline. However, the online peak search interest for suicide-seeking was greater than help-seeking. This provides support for a strong Werther effect, possibly associated with poor quality of media reporting of celebrity suicide. There is an urgent need for taking steps to improve the quality of media reporting of suicide in India.

1. Introduction

Suicide is a major public health problem, and is one of the leading causes of mortality globally (Naghavi, 2019). The reported deaths due to suicide in India is highest among countries worldwide (Dandona et al., 2018). Studies have reported that media reports of celebrity suicide stimulate imitation acts in vulnerable population (Gould et al., 2003). Also, repeated insensible media coverage may act as a source of misinformation that suicide is an acceptable solution to ongoing difficulties in life. This has been supported by the bulk of available literature, with a recent meta-analysis reporting a 13 % increased risk of suicide (95 % confidence interval of 8–18 %; median follow-up duration of 28 days) in the period following the media report of celebrity suicide death (Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2020). Media reporting of suicide is a double-edged sword, with inappropriate and sensational reporting of suicide news leading to copycat phenomenon or Werther effect. Whereas, sensible media reporting of suicide along with media involvement in spreading preventive information shown to minimise copycat eff ;ects, and has been shown to be eff ;ective in reducing suicide deaths (Cheng et al., 2018). Thus, researchers have advocated for a more responsible descriptive reporting of suicide news, with emphasis on sharing preventive information related to suicide. This includes reporting upon how people could adopt alternative coping strategies to deal with life stresses or depressed mood along with sharing links of educative websites or suicide helplines; and has been shown to be associated with decreased suicide suicidal behaviour and ideation in vulnerable population (Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2010; Till et al., 2017). Therefore, media reporting of suicide-related preventive information has been associated with positive effects on subsequent suicide rates and ideation. This is described as the Papageno effect, and acts as a counterforce to the Werther Effect (Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2017)

Responsible media reporting of suicide is considered as the best available strategy to counter the harmful effects of media reportage (Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2020). In recent years, internet is being increasingly used by the public for seeking health-related information; and information related to mental health related disorders or problems also being widely available online (Amante et al., 2015). It is understandable, that several researchers have expressed concerns about vulnerable individuals either using internet to access pro-suicide information (e.g. methods of suicide) or inadvertently being exposed to online news or information which negatively affects their thoughts or mood and promote suicidal behaviours in them (Arendt and Scherr, 2017; Till and Niederkrotenthaler, 2014). However, internet also provides a host of suicide prevention related information and resources which could in turn decrease the risk of suicide (Biddle et al., 2008). Further, news over internet and social media is able to reach to a large number of vulnerable and difficult to reach youth population; and has been shown to potentially influence the public opinion, attitudes, and behaviours over wide range of topics (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010). Thus, it is important to explore the quality of online media reporting of celebrity suicide in India. This would in turn help in better understanding the role played by this new electronic medium in either predisposing or protecting people with suicidal ideas or death wishes.

There has been limited literature available assessing the quality of media reporting of suicide in India. Most of the studies assessed media reporting of suicide in general population, and only one study had focused on celebrity suicide specifically (Harshe et al., 2016). However, that study took death of Robin Williams (Hollywood movie actor of US origin) as the reference event and was done about four years back. Further, all the available studies have assessed newspapers in a particular region and were conducted prior to Press Council of India (PCI) issuing media reporting guidelines on suicide and mental illness in India. The PCI has adopted the guidelines of World Health Organization (WHO) report on Preventing Suicide (Press Council of India, 2020). It forbids undue repetition of stories, placing stories in prominent positions, explicit description of the suicide method, providing details about the suicide location, using sensational headlines and reporting photographs of the person. There might be some change in the quality of media reporting of suicide in recent years, more specifically after the PCI guidelines. Further, the WHO guidelines for responsible reporting are valid for all types of media, and it is important to explore the role played by the online media in current digital world. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge there has been no study from Indian context yet exploring the association between media reporting of death of celebrity by suicide and subsequent suicidal behaviour in the general population.

The official figures for deaths due to suicide in India is released by the National Crimes Record Bureau (NCRB) in India. However, the NCRB has stopped releasing this data since 2016 and the official suicide statistics have not been made public till now. Further, it is usually available at the end of the year and does not provide data on a weekly basis. Moreover, any other system of directly recording suicide statistics in India will face the challenges associated with collecting vital statistics through sub-optimal existing vital registration system, misclassification, and under-reporting of suicide deaths due to associated legal complications and social stigma around suicide death in the family(Armstrong and Vijayakumar, 2018). Additionally, the restrictions imposed on movement of people and social distancing guidelines to be followed during the current COVID-19 pandemic, makes it even more difficult to access the study population in a systematic manner for assessment of suicide risk using traditional research methods (Bidarbakhtnia, 2020).

The above described limitations could be addressed by employing research methods and techniques involving the study of internet-based search behaviours and social media content. Infodemiology has been defined as “the science of distribution and determinants of information in an electronic medium, specifically the Internet, or in a population, with the ultimate aim to inform public health and public policy” (Eysenbach, 2009). Google Trends is an analytical tool available for tracking the online search interests of the population. The evidence supporting correlation between increased online search interest for particular suicide-related search queries using Google search engine and the actual number of suicides in that region during that particular time-period has been increasing over the past two decades (Lee, 2020). Moreover, recent studies have shown that data obtained using Google Trends for suicide-seeking keywords could be used for predicting actual monthly suicide numbers at the Country level (Kristoufek et al., 2016). Thus, in the present study we monitored the changes in internet search volumes for keywords representing suicide-seeking and help-seeking behaviours using the Google Trends platform as a proxy marker to assess the impact of recent celebrity suicide in India.

Sushant Singh Rajput (SSR) was a much-loved Indian actor who died by suicide on June 14, 2020. This was reported by various national and international media, and was considered as the reference event in this study. Thus, the present study aimed to assess the quality of online media reporting of a celebrity suicide in India, and evaluate its adherence with the WHO guidelines for responsible media reporting of suicide. Further, we aimed to examine the change in internet search volumes for keywords representing suicide-seeking and help-seeking behaviours of the population immediately following the celebrity suicide. This would provide indirect evidence for either existence or absence of the Werther and the Papageno effect at the population level in India.

2. Materials and method

The online media reports related to the theme of death of SSR by suicide on 14th June were retrieved using the Google News online platform (https://news.google.com). The search was conducted on 20th June, 2020 in the tor browser, using search terms “Sushant”, “Singh”, “Rajput”, “died”, “death” and “suicide”. The search period was restricted between 14 to 20 June, 2020. This corresponded to first week immediately after the reference event. A total of 214 reports published on various international, national, and regional online news and entertainment media portals were retrieved. Fourteen of them contained either only videos or were not related to theme of the present study, and were excluded. Thus, a total of 200 articles were selected for further analysis.

The news headlines were analysed to generate a word cloud (using a word cloud generator available at https://www.wordclouds.com) representing the commonly used terms in the online media reports covering SSR death. Two authors independently reviewed and extracted information related to different news report characteristics using a pre-designed format in Microsoft Excel. It included information pertaining to descriptive characteristics of the news report such as the date of publishing, name of the news publisher, type media agency, and primary focus of the article being descriptive or commentary. The quality of articles was evaluated using a checklist prepared on the basis of WHO responsible media reporting of suicide guidelines (see Supplementary Table 1), and is similar to that used in previous studies (Armstrong et al., 2018). The items were coded as “1” if the guideline was violated and “0” if the guideline was adhered to in the report. Two trained researchers independently reviewed and extracted information following the above described procedure. Any discrepancy or disagreement between the two researchers was resolved by consensus. The third author was consulted if needed. The data were analysed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). The descriptive (frequency and percentage) and inferential statistics (chi-square and Fishers’ exact test) were conducted. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant for all tests.

The Google Trends utilizes an algorithm to give normalized relative search volume (RSV) for the keyword(s) searched for a specified geographical region and time period. The RSV represents how frequently a given search query has been searched on the Google search engine, compared to the total number/volume of Google searches conducted in the same geographical region over the selected time period. The RSV values range from zero (representing very low search volumes) to 100 (peak search volume for that query). Google Trend analysis was conducted to evaluate the online search interest for keywords representing suicide-seeking and help-seeking behaviours of the population for the month of June 2020. The initial list was made based on the review of available literature, which was finalized by the process of consensus building between two authors R.G. and S.S (qualified psychiatrists with clinical and research experience of working with people with mental illness and suicidal ideas/attempts) based on the face validity of search terms. The examples of suicide-seeking keywords included in the study were ‘commit suicide’, ‘suicide method’, and ‘kill myself’. Whereas, the help-seeking keywords such as ‘suicide help’, ‘suicide treatment’, and ‘psychiatrist’ were used. The four Google Trends options of Region, Time, Category, and Search type were specified as India, from 1 June to 30 June 2020, all categories, and web search in the present study. The “plus” (+) function from google trends was used to integrate the search volume (RSV) of all suicide-seeking terms and help-seeking keywords. A Graph showing daily variation in RSV for suicide-seeking and help-seeking keywords was constructed. The change in mean RSV value for the suicide-seeking and help-seeking keywords after the reference event, when compared to baseline was analysed by applying the Mann Whitney-U test. The complete list of keywords used in this study along with other details pertaining to the Google Trends methodology are described in Supplementary Table 2.

The information used in this study involved published online media reports and data related to the volume of anonymized web searches made during a given time period, both of which were freely available in the public domain. Further, no patient or participant was approached directly in this study. Thus, no written ethical permission was required from the ethics committee.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of media headlines

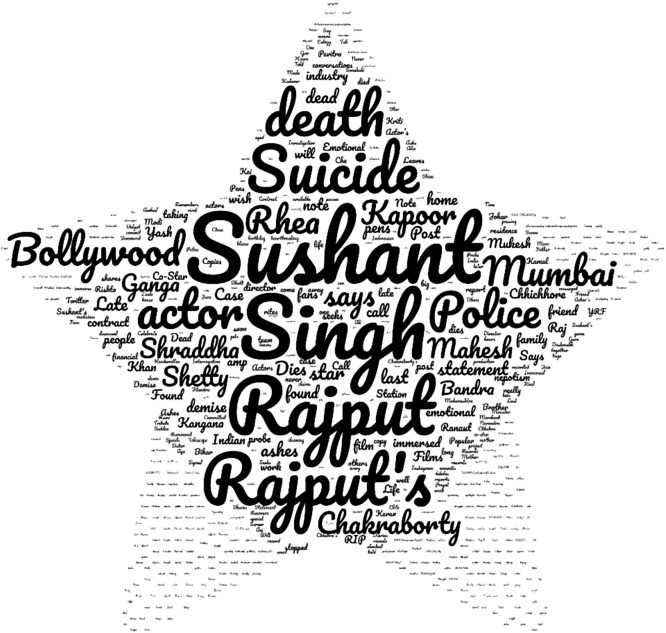

The frequency of different words used in the headlines of the 200 media reports analysed in the present study were depicted as a word cloud, with the size of font used being representative of its frequency (Fig. 1 ). Apart from the words in the name of SSR, the most commonly used words were "suicide", "death", "actor", "police", "Bollywood", "Mumbai", "Rhea", and "Kapoor" in decreasing order of frequency. This suggested that a significant proportion of headlines used words like suicide, police or Bollywood to sensationalize or glamourize the headlines, with no significant difference between news media (37.5 %; 37/122) and entertainment media (42.0 %; 37/88) headlines (χ2 =0.426, p = 0.56). The term “suicide” was used with similar frequency in both news media (n = 18;16.1 %) and entertainment media (n = 15;17 %) headlines. Only two news media reports (n = 2;1.8 %) mentioned ‘hanging’ term in the headlines. The location of suicide was mentioned in two news media (1.8 %) and two (2.3 %) entertainment media headlines.

Fig. 1.

Word cloud of media report headlines analysed in the study (N = 200).

3.2. Analysis of media reports

The selected media reports were published from various media platforms: international news group, 9% (n = 18); national news group, 28.5 % (n = 57); regional news group, 18.5 % (n = 37); and entertainment blogs, 44 % (n = 88). Seventeen news media platforms had reported the story four or more times in the immediate one-week period following the SSR suicide, with Hindustan Times (6), NDTV (6), Republic World (6), Times of India (5), DNA (5), India TV (4), The Indian Express (4) and Times Now (4) contributing to 41.5 % (n = 83/200) of the articles. Around 17 % (n = 34) articles were published on 14th June 2020, while 49.5 % of articles (n = 99) were published on 18th June,2020. About 45.5 % (n = 91/200) articles were focussed at direct descriptive reporting of suicide.

The descriptive analysis of media reports for different potentially harmful and helpful media report characteristics are described in Table 1, Table 2 respectively. About 85.5 % of reports violated the recommendation provided in the guideline, by including at least one potentially harmful information. There was significant association between the type of news media and the use of sensational language [χ2(3) = 9.774 (p < 0.021)]. Regional and entertainment media used more sensational language compared to national and international media. There was significant association between the type of news media and provision of information about where to seek help [χ2(1) = 15.98 (p < 0.001)]. Mainstream news media provided such information more than entertainment media. Final social media posts were shared more by national media compared to international, regional and entertainment media [χ2(3) = 9.91 (p < 0.019)].

Table 1.

Potentially harmful media reporting characteristics according to World Health Organization suicide reporting guidelines.

| Media report characteristics | Total n (%) |

News n (%) |

Entertainment n (%) |

Test statistic χ2 (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of sensational language | 116 (58) | 60 (53.6) | 56 (63.6) | 2.049 a (0.15) |

| Use of ‘committed’ term | 37 (18.5) | 19 (17) | 18 (20.5) | 0.398 a (0.53) |

| Reporting of suicide method | 69 (34.5) | 42 (37.5) | 27 (30.7) | 1.014 a (0.32) |

| Detailed account of method | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Suicide site reported | 119 (59.5) | 68 (60.7) | 51 (58) | 0.156 a (0.69) |

| Negative life events mentioned | 19 (9.5) | 7 (6.3) | 12 (13.6) | 3.127 a (0.77) |

| Reference to the cause of suicide | 34 (17) | 15 (13.4) | 19 (21.6) | 2.347 (0.13) |

| Monocausal explanation for suicide | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (2.3) | 2.571 b (0.19) |

| Photograph of the celebrity | 171 (85.5) | 95 (47.5) | 76 (38) | 0.95 a (0.75) |

| Final social media posts of the celebrity | 13 (6.5) | 10 (8.9) | 3 (3.4) | 2.47 b (0.116) |

| Social media posts of bereaved persons | 106 (53) | 59 (52.7) | 47 (53.4) | 0.011 a (0.92) |

| Suicide note reported | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Sensational headline | 79 (39.5) | 42 (21) | 37 (18.5) | 0.426 a (0.51) |

| Word ‘suicide’ in headline | 33 (16.5) | 18 (9) | 15 (7.5) | 0.34 a (0.85) |

| Mention of suicide method in headline | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | 1.587b (0.51) |

| Life event(s) in headline | 8 (4) | 1 (0.5) | 7 (3.5) | 6.4 b (0.23) |

| Mention of location in headline | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.6 b (1) |

Chi-square test.

Fishers Exact test. *p-value< 0.05.

Table 2.

Potentially helpful media reporting characteristics according to World Health Organization suicide reporting guidelines.

| Media report characteristics | Total n (%) |

News n (%) |

Entertainment n (%) |

Test statistic (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of ‘died by Suicide’ or ‘took his life’ term | 150 (75) | 88 (78.6) | 62 (70.5) | 1.732 a (0.19) |

| Information to seek help | 26 (13) | 24 (21.4) | 2 (2.3) | 15.98 (<0.001) |

| Educate about suicide prevention | 4 (2) | 4 (3.6) | 0 | 3.207 b (0.13) |

| Coping with suicide thoughts | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0.79 b (1) |

| Focus on life & contribution to society | 46 (23) | 28 (25) | 18 (20.5) | 0.575 a (0.45) |

| Recognises link with mental illness | 57 (28.5) | 30 (26.8) | 27 (30.7) | 0.367 a (0.54) |

| Expert opinion | 4 (2) | 4 (3.6) | 0 | 3.207 b (0.13) |

| Research findings reported | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0.79 b (1) |

| Suicide statistics reported | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0.79 b (1) |

| Dispel myths regarding suicide | 3 (1.5) | 3 (2.7) | 0 | 2.393 b (0.25) |

Chi-square test.

Fishers Exact test.*p-value< 0.05.

3.3. Google trends analysis

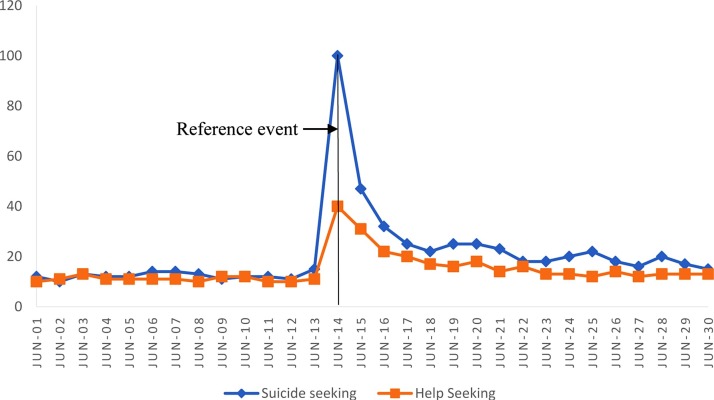

The median and inter-quartile range (IQR) values of RSV for suicide-seeking keywords in the two-weeks before and after the death of SSR on 14 June 2020 were 12 (IQR: 11.5–13.5) and 22 (IQR: 18–25) respectively. Whereas, the median and IQR values of RSV for suicide-seeking keywords in the two-weeks before and after the death of SSR were 11 (10–11.5) and 14 (13–19) respectively. There was a significant increase in RSV for suicide-seeking (U = 0.5; Z= -4.62; p < 0.001) and help-seeking (U = 6.5; Z=-4.39; p < 0.001) keywords after the reference event, when compared to baseline. However, the online peak search volume and search interest for suicide-seeking was greater than help-seeking as shown in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Google Trends graph depicting change in online search interest for queries representing suicide-seeking and help-seeking behaviours in India for the month of June 2020 (Results are expressed as relative normalized search volume numbers).

4. Discussion

The present study analysed the online media reports related to the theme of a popular Bollywood movie actor’s suicide, and compared it against the WHO media reporting guidelines for suicide. The story of this recent celebrity suicide received widespread coverage across different online news platforms, including national and international news agencies. Overall, majority of articles showed poor adherence with the WHO guidelines while reporting the celebrity suicide. The reports had minimal focus on educating the public the regarding suicide. Further, the change in online search interest for different keywords related to “suicide-seeking” and “help-seeking” behaviours after this event were analysed to explore for possible Werther and Papageno effects.

A substantial proportion of articles did not follow most of the recommendations. About 58 % articles used sensational language, 59.5 % articles mentioned suicide site, 17 % articles suggested possible cause for suicide which was not related to poor mental health. A study assessing the quality of suicide reporting in Indian print media found increase in prominence of suicide reports after the celebrity suicide (Harshe et al., 2016). It speculated that the most likely reason for sensationalism in media reporting of suicide might be to enhance the readership. Further, only 13 % articles provided information about where to seek help for suicidal thoughts. A previous study evaluating the newspaper coverage of celebrity suicide in United States against ‘Mindset’ recommendations for reporting suicide, found 46 % articles provided details about suicide method and only 11 % provided information about help-seeking (Carmichael and Whitley, 2019). Previous studies from India found minimal adherence to media reporting recommendations for suicide in the print media. Menon et al found that the method of suicide was reported in 99.1 % articles and locations of suicide was reported in 86.5 % articles (Menon et al., 2020). Chandra et al. showed that 80 % articles reported suicide location and 61 % suggested monocausality for suicide (Chandra et al., 2014). The high frequency of harmful reporting characteristics observed in the present study is consistent with the low adherence to WHO guidelines reported in other neighbouring Asian countries as well (Arafat et al., 2020a). Studies from Bangladesh (Arafat et al., 2020b), Indonesia (Nisa et al., 2020) and Sri Lanka (Brandt Sørensen et al., 2019) have also reported non-adherence to WHO recommendations in print media such as reporting of suicide method, description of suicide note and inclusion of personal identification characteristics in reports. The headlines of the online reports included in the current study used the term ‘suicide’ in 18 % articles. Previous studies on print media from India reported “suicide” mentioned in headlines of 68.6 % articles (Chandra et al., 2014) and 30.31 % articles (Harshe et al., 2016).

Refreshingly, in the present study 81.5 % articles did not use the word ‘commit’ or related terms while reporting suicide, and 65.5 % articles did not mention the suicide method in the reports. This is a welcome improvement in media reportage of suicide, which might be due to the positive effect of PCI adopting guidelines on media reporting of suicide in September 2019 based on the WHO guidelines (Vijayakumar, 2019). However, photograph of the celebrity was provided by 47.5 % of news media reports and 38 % of entertainment media reports. Publication of photograph of a person with mental illness without the individual’s or his/her next of kin’s consent in case of suicide violates section 24 (1) of the Mental Health Care Act, 2017 in India (Mental Healthcare Act, 2017). Further, sensational language was used to report celebrity suicide by majority of news media and entertainment media reports. Among the news media, regional media used sensational language more frequently than national and international media. Final social media posts were reported by 8.9 % news media and 3.4 % entertainment media. Among the different media platforms, national media shared final social media posts more frequently than international, regional and entertainment media. Mainstream news media provided information about where to seek help more frequently than entertainment media. This is in line with a study on print media from India, that reported vernacular newspapers to be more compliant with WHO suicide reporting guidelines compared to English language newspapers (Menon et al., 2020).

Moreover, in terms of providing potentially helpful information, only one article provided research findings and population level statistics regarding suicide. Only two percent articles included expert opinion from health professionals while reporting suicide. Also, 28.5 % articles tried to address the link between suicide and poor mental health in the present study. This highlights the need to emphasize the importance of including such information in media reports of suicide among journalists and news editors. It helps in increasing the awareness about mental health problems among the general population and encourage them to seek treatment for the same. A previous study assessing South Indian newspapers found that a few articles recognised the link between suicide and psychiatric disorders or substance use disorders (Menon et al., 2020). Similarly, previous studies from India evaluating the reporting of suicides in newspapers found that only few articles tried to educate public about the issue of suicide by including opinion from health professionals, research findings or information about suicide prevention programmes (Chandra et al., 2014; Harshe et al., 2016; Menon et al., 2020).

One possible solution is to have a uniform national suicide reporting guideline for the media of the entire country. A similar approach has been shown to be beneficial in improving the overall quality of media reporting of suicide in Australia (Pirkis et al., 2009). However, as prior researchers have pointed out (Vijayakumar, 2019), merely framing of guidelines may not help in improving the quality of media reporting of suicide. A continuous collaborative approach involving both mental health experts and media professionals should be adopted to sensitize them about the available research evidence backing these media reporting guidelines has been shown to successful in improving adherence to media reporting guidelines (Bohanna and Wang, 2012). Also, there should be regular workshops held for media professionals to provide them with adequate training and support in covering mental health and suicide-related topics.

The findings from google trend analysis showed a significant increase in online search interest for terms representing both suicide-seeking and help-seeking behaviours after the SSR death. The surge in internet search volume for suicide-seeking keywords along with media reports of copycat suicides from different parts of India provides evidence of the Werther effect (Hindustantimes, 2020; News18, 2020, p. 18; Timesofindia, 2020). There are several possible mechanisms described in the literature to explain the observed increase in suicidal behaviour among the general population associated with media reporting of celebrity suicide (Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2020). First, people may identify with the deceased celebrities, which is usually more common in case of entertainment celebrities due to their strong public identity and following. Second, repeated insensible media reporting might lead to normalization of suicide as an acceptable way out of their problems by the vulnerable population. Third, media reporting about the method of celebrity suicide might increase the cognitive availability of that method and remove ambivalence about which method to choose for suicide in vulnerable individuals, leading to an increase in suicide by the same method among the vulnerable population. Interestingly, there was also smaller but significant increase in the internet search volume for help-seeking keywords. The peak search volume for help-seeking and suicide-seeking keywords was observed on the day of SSR’s death, with a lower peak RSV and subsequently lower daily RSVs for help-seeking terms as compared to suicide-seeking terms among the general population. This suggests a weaker Papageno effect as compared to the Werther effect, possibly due to poor adherence to the WHO suicide reporting guidelines by the online and other types of media in India while covering the celebrity suicide (Newslaundry, 2020).

There only a few studies that have assessed the fidelity of suicide reporting in India, with almost of the studies having evaluated the quality of media reporting of suicide in general population and included only few print media newspapers. Thus, our study provides valuable addition to bridge these gaps in the existing literature on media reporting of celebrity suicide from India. Further, a wide range of online media reports were analysed in this study for the first time in Indian settings to the best of our knowledge. Further, the use of a novel Google Trends analysis to show an increased online search interest for suicide-seeking keywords immediately after the reference celebrity suicide provided support for the existence of Werther effect in the Indian context. However, there are certain limitations as well which should be kept in mind while interpreting the findings of this study. The study focussed only on English language media reports. We did not assess print media without online version, television, radio and social media. This might be an important area for future research, since studies from Western countries suggest television coverage or social media (e.g. Twitter) to be associated with increased suicide rates (Jashinsky et al., 2014). Further, the relationship between people searching for suicide-seeking keywords might not be as clear as that observed for people with certain infectious disease like the influenza, with Google Trends analysis of data about searching for disease symptoms or other disease-related information being used to predict their incidences or outbreaks prior to the traditional methods of reporting an outbreak (Cao et al., 2017; Ginsberg et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2018). This is likely due to the fact that that someone who searched about suicide might not be actually suicidal, and may or may not kill themselves during the specified study period. Further, the keywords representing suicide-seeking and help-seeking behaviours were derived from review of literature from Western countries mostly followed by consensus amongst the authors based on their face validity. However, the search methodology used for doing the Google Trends analysis in the present study is in accordance with the guidelines for conducting a robust Google Trends research (Nuti et al., 2014).

5. Conclusion

The quality of media reporting of celebrity suicide on online media in India is poor when compared to adherence with the WHO guidelines or the PCI guidelines. In terms of including potentially harmful information, about 85.5 % of reports violated at least one recommendation provided in the guideline. Further, compliance with recommendations of including potentially helpful information about creating awareness about suicide and possible ways of seeking help for suicidal thoughts was very low, with only few articles 13 % articles providing information about where to seek help for suicidal thoughts or ideation. There was a significantly greater increase in the online search interest for suicide-seeking keywords after the recent celebrity suicide. This in turn provides support for a strong Werther effect, possibly associated with poor quality of media reporting of celebrity suicide. The results emphasize the need for an increased collaboration, promotion, and advocacy by experts for uptake of existing media reporting guidelines on suicide by journalists and other stakeholders. There is an urgent need for research on understanding the effects of media reporting of suicide at general population’s suicidal acts and thoughts.

Financial disclosure

“None”.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102380.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Amante D.J., Hogan T.P., Pagoto S.L., English T.M., Lapane K.L. Access to care and use of the internet to search for health information: results from the US national health interview survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015;17:e106. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arafat S.M.Y., Kar S.K., Marthoenis M., Cherian A.V., Vimala L., Kabir R. Quality of media reporting of suicidal behaviors in South-East Asia. Neurol. Psychiatry Brain Res. 2020;37:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.npbr.2020.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arafat S.M.Y., Mali B., Akter H. Do Bangladeshi newspapers educate public while reporting suicide? A year round observation from content analysis of six national newspapers. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;48 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2019.101920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendt F., Scherr S. Optimizing online suicide prevention: a search engine-based tailored approach. Health Commun. 2017;32:1403–1408. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1224451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong G., Vijayakumar L. Suicide in India: a complex public health tragedy in need of a plan. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3 doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30142-7. e459–e460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong G., Vijayakumar L., Niederkrotenthaler T., Jayaseelan M., Kannan R., Pirkis J., Jorm A.F. Assessing the quality of media reporting of suicide news in India against World Health Organization guidelines: a content analysis study of nine major newspapers in Tamil Nadu. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2018;52:856–863. doi: 10.1177/0004867418772343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidarbakhtnia A. 2020. Surveys Under Lockdown; a Pandemic Lesson. [Google Scholar]

- Biddle L., Donovan J., Hawton K., Kapur N., Gunnell D. Suicide and the internet . BMJ. 2008;336:800–802. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39525.442674.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohanna I., Wang X. Media guidelines for the responsible reporting of suicide: a review of effectiveness. Crisis. 2012;33:190–198. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt Sørensen J., Pearson M., Andersen M.W., Weerasinghe M., Rathnaweera M., Rathnapala D.G.C., Eddleston M., Konradsen F. Self-harm and suicide coverage in Sri Lankan newspapers. Crisis. 2019;40:54–61. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao B., Liu C., Durvasula M., Tang W., Pan S., Saffer A.J., Wei C., Tucker J.D. Social media engagement and HIV testing among men who have sex with men in China: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017:19. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael V., Whitley R. Media coverage of robin williams’ suicide in the United States: a contributor to contagion? PLOS ONE. 2019;14:e0216543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra P.S., Doraiswamy P., Padmanabh A., Philip M. Do newspaper reports of suicides comply with standard suicide reporting guidelines? A study from Bangalore. India. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2014;60:687–694. doi: 10.1177/0020764013513438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Q., Chen F., Lee E.S.T., Yip P.S.F. The role of media in preventing student suicides: a Hong Kong experience. J. Affect. Disord. 2018;227:643–648. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandona R., Kumar G.A., Dhaliwal R.S., Naghavi M., Vos T., Shukla D.K., Vijayakumar L., Gururaj G., Thakur J.S., Ambekar A., Sagar R., Arora M., Bhardwaj D., Chakma J.K., Dutta E., Furtado M., Glenn S., Hawley C., Johnson S.C., Khanna T., Kutz M., Mountjoy-Venning W.C., Muraleedharan P., Rangaswamy T., Varghese C.M., Varghese M., Reddy K.S., Murray C.J.L., Swaminathan S., Dandona L. Gender differentials and state variations in suicide deaths in India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3:e478–e489. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30138-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G. Infodemiology and infoveillance: framework for an emerging set of public health informatics methods to analyze search, communication and publication behavior on the internet. J. Med. Internet Res. 2009;11:e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg J., Mohebbi M.H., Patel R.S., Brammer L., Smolinski M.S., Brilliant L. Detecting influenza epidemics using search engine query data. Nature. 2009;457:1012–1014. doi: 10.1038/nature07634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould M., Jamieson P., Romer D. Media contagion and suicide among the Young. Am. Behav. Sci. 2003;46:1269–1284. doi: 10.1177/0002764202250670. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harshe D., Karia S., Harshe S., Shah N., Harshe G., De Sousa A. Celebrity suicide and its effect on further media reporting and portrayal of suicide: an exploratory study. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2016;58:443. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.196704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindustantimes . Hindustan Times; 2020. Sushant Singh Rajput’S Fan Ends Life in Visakhapatnam: Report [WWW Document] . URL https://www.hindustantimes.com/bollywood/sushant-singh-rajput-s-fan-ends-life-in-visakhapatnam-report/story-QKOexaEj1X6nNPoXBOobKK.html (accessed 8.1.20) [Google Scholar]

- Jashinsky J., Burton S.H., Hanson C.L., West J., Giraud-Carrier C., Barnes M.D., Argyle T. Tracking suicide risk factors through twitter in the US. Crisis. 2014;35:51–59. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A.M., Haenlein M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010;53:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kristoufek L., Moat H.S., Preis T. Estimating suicide occurrence statistics using google trends. EPJ Data Sci. 2016;5:1–12. doi: 10.1140/epjds/s13688-016-0094-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.-Y. Search trends preceding increases in suicide: a cross-correlation study of monthly Google search volume and suicide rate using transfer function models. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;262:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V., Kaliamoorthy C., Sridhar V.K., Varadharajan N., Joseph R., Kattimani S., Kar S.K., Arafat S.Y. Do Tamil newspapers educate the public about suicide? Content analysis from a high suicide Union Territory in India. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020933296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental Healthcare Act, 2017.

- Naghavi M. Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ. 2019:364. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- News18 . 2020. Andaman’s Minor Girl Hangs Herself After She Went Into Depression Over Sushant Singh Rajput’s Suicide [WWW Document] URL https://www.news18.com/news/movies/andamans-minor-girl-hangs-herself-after-she-went-into-depression-over-sushant-singh-rajputs-suicide-2675233.html (accessed 8.1.20) [Google Scholar]

- Newslaundry . 2020. Are Top Indian Newspapers Complying With Guidelines on Suicide Reporting? [WWW Document] URL https://www.newslaundry.com/2020/04/17/are-top-indian-newspapers-complying-with-guidelines-on-suicide-reporting (accessed 8.1.20) [Google Scholar]

- Niederkrotenthaler T., Voracek M., Herberth A., Till B., Strauss M., Etzersdorfer E., Eisenwort B., Sonneck G. Role of media reports in completed and prevented suicide: Werther v. Papageno effects. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2010;197:234–243. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederkrotenthaler T., Stack S., Stack S. Routledge; 2017. Media and Suicide : International Perspectives on Research, Theory, and Policy. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niederkrotenthaler T., Braun M., Pirkis J., Till B., Stack S., Sinyor M., Tran U.S., Voracek M., Cheng Q., Arendt F., Scherr S., Yip P.S.F., Spittal M.J. Association between suicide reporting in the media and suicide: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ m575. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisa N., Arifin M., Nur M.F., Adella S., Marthoenis M. Indonesian online newspaper reporting of suicidal behavior: compliance with world health organization media guidelines. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020;66:259–262. doi: 10.1177/0020764020903334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuti S.V., Wayda B., Ranasinghe I., Wang S., Dreyer R.P., Chen S.I., Murugiah K. The use of google trends in health care research: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkis J., Dare A., Blood R.W., Rankin B., Williamson M., Burgess P., Jolley D. Changes in media reporting of suicide in Australia between 2000/01 and 2006/07. Crisis. 2009;30:25–33. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.30.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press Council of India . 2020. Guidelines Adopted by the PCI on Mental illness/reporting of Suicide Cases. [Google Scholar]

- Till B., Niederkrotenthaler T. Surfing for suicide methods and help: content analysis of websites retrieved with search engines in Austria and the United States. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2014;75:886–892. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Till B., Tran U.S., Voracek M., Niederkrotenthaler T. Beneficial and harmful effects of educative suicide prevention websites: randomised controlled trial exploring papageno v. Werther effects. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2017;211:109–115. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.177394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timesofindia . Times India; 2020. Patna: Girl Hangs Self After Watching Sushant Singh Rajput’s Suicide News | Patna News - Times of India [WWW Document] URL https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/patna/patna-girl-hangs-self-after-watching-sushant-singh-rajputs-suicide-news/articleshow/76416345.cms (accessed 8.1.20) [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumar L. Media Matters in suicide – indian guidelines on suicide reporting. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2019;61:549. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_606_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Chai Y., Li X., Young S.D., Zhou J. Using internet search data to predict new HIV diagnoses in China: a modelling study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e018335. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.