Several instances of COVID related suicidal behaviour have been reported from various nations (Goyal et al., 2020; Mamun and Ullah, 2020). It is of interest that the links between COVID-19 and mental health has been a priority for this journal (Tandon, 2020). Examining the relationship between COVID-19 and suicidality from a biopsychosocial perspective has the potential to improve our understanding of individual suicidal behaviour and inform suicide prevention strategies both at an individual as well as population level; this is what we attempt below.

-

1

Biological links

Mounting evidence points to pronounced inflammatory changes in the brain and blood of patients with suicidal ideation, attempts as well as completed suicide. The strength of the evidence has prompted researchers to evaluate the role of inflammatory biomarkers in suicide risk assessment, with some promising results (Bergmans et al., 2019). Likewise, seropositivity for respiratory coronaviruses has been linked to increased suicide risk. Though the exact mechanisms underpinning this association remain unclear, it is thought to be related to the neurotropic potential of the virus and their ability to trigger a sustained central and peripheral inflammatory reaction, both of which may increase vulnerability for suicidal behavior (Okusaga et al., 2011). Treatments, that attenuate these inflammatory changes, may have beneficial spinoffs on suicidal behavior and merit further evaluation (Menon and Padhy, 2020).

-

2

Sociological pathways

Multiple, overlapping sociological pathways may contribute to the relationship between novel coronavirus pandemic and suicidal behaviour. Firstly, the fear of contracting the infection and spreading it to family members may trigger altruistic suicidal ideas (India.com News Desk, 2020); these concerns may be more pronounced among high risk sub-populations such as policemen and health care workers (HCW).

Next, pandemic containment measures such as lockdown and social distancing norms may engender feelings of isolation and entrapment as well as a lack of general social direction, potentially driving anomic suicidal behaviour; suicides among migrant workers (News18 India, 2020), attributed to a combination of unemployment, feelings of isolation due to separation from family and apprehension about future may be an example of this. Simultaneously, for individuals lacking sufficient social integration, prolonged containment measures such as lockdown may lead to a sense of being alienated from others and result in egoistic suicides.

Finally, being subjected to prolonged social regulations that restrict individual freedom may trigger fatalistic thoughts and despair about the future, particularly among groups who are already experiencing such restrictions. A case in point is the reports of post lockdown suicide among those incarcerated (Grierson, 2020), ostensibly driven by pessimism and despair due to the strict containment measures.

-

3

Personality and psychosocial factors

One of the earliest reports on COVID related suicide from India mentioned the possible reasons as fear of acquiring COVID-19 (Goyal et al., 2020). Subsequent reports have highlighted the proximal role of apprehensions about contracting COVID-19 as a potential driver of suicide (Mamun and Ullah, 2020).

But why do these apprehensions affect some more than others? The answer to this may lie in personality variables such as intolerance to uncertainty, a construct central to anxiety disorders. This construct refers to dispositional fear wherein the unknown is perceived intensely, resulting in anxiety and emotional problems (Fergus, 2013). There are studies, in the present pandemic, that have linked intolerance of uncertainty to mental wellbeing of subjects, with fear of COVID-19 playing a key mediating role in this relationship (Satici et al., 2020). This merits further investigation across settings and cultures.

Other relevant psychosocial factors that may be operating here include economic adversity, unemployment, poverty and resultant hardships induced by the pandemic. Furthermore, remaining confined to home increases access to means such as firearms/pesticides; this enhances the chances of a person acting upon his/her suicidal ideation. Means restriction has been shown to be one of the most effective interventions for suicide prevention (Menon et al., 2018). But this is patently hard to achieve when people are home bound.

Finally, the role of media in triggering suicidal behavior must not be ignored. Irresponsible and sensationalized reporting of suicides can precipitate suicidal behaviour; but in the context of the pandemic can also exacerbate fear, compound stigma and heighten suicide risk. Media professionals must exercise caution while reporting COVID-19 related suicides as it is a key population level suicide prevention strategy (Zalsman et al., 2016).

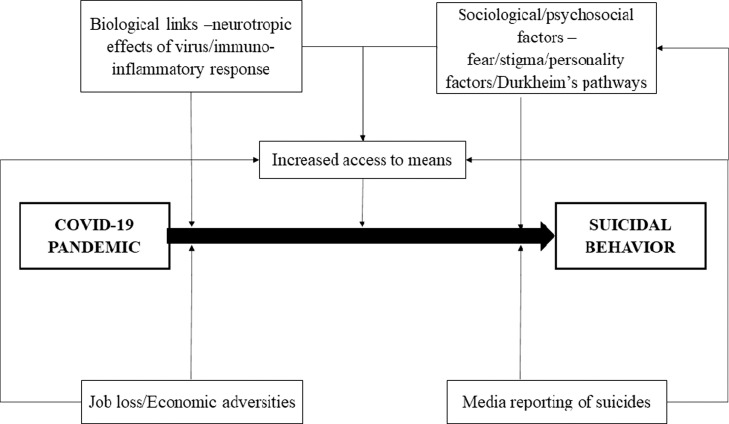

To sum up, we advocate a biopsychosocial approach (Fig. 1 ) to understand suicidal behaviour in the context of the pandemic. Interventions for COVID related suicidality would follow this understanding and can be both population based (such as media level reporting strategies or mass media information campaigns) or individually focussed (such as anti-inflammatory therapies or relevant psychosocial therapies). Often, practice precedes science or evidence in medicine and given the acute nature of the pandemic and suicides, clinicians may be well served by following a structured approach to suicide prevention activities, so that every possible contributor to suicide is suitably addressed. We owe such diligence to our patients, who deserve nothing less than the best we can offer.

Fig. 1.

A biopsychosocial framework to understand the relationship between COVID-19 outbreak and suicidal behavior.

Financial disclosures

There are no financial disclosures or sources of support for the present work.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors reported no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgments

None.

References

- Bergmans R.S., Kelly K.M., Mezuk B. Inflammation as a unique marker of suicide ideation distinct from depression syndrome among U.S. Adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;245:1052–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus T.A. A comparison of three self-report measures of intolerance of uncertainty: an examination of structure and incremental explanatory power in a community sample. Psychol. Assess. 2013;25:1322–1331. doi: 10.1037/a0034103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal K., Chauhan P., Chhikara K., Gupta P., Singh M.P. Fear of COVID 2019: first suicidal case in India! Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;49 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grierson J. Alarm over five suicides in six days at prisons in England and Wales. The Guardian. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- India.com News Desk . News India.com; 2020. “I Might Spread COVID-19 to My Family”, IRS Officer Commits Suicide in Delhi’s Dwarka [WWW Document]. India News Break. News Entertain. URL https://www.india.com/news/india/i-might-spread-covid-19-to-my-family-irs-officer-commits-suicide-in-delhis-dwarka-4058218/ (Accessed 6.18.20) [Google Scholar]

- Mamun M.A., Ullah I. COVID-19 suicides in Pakistan, dying off not COVID-19 fear but poverty? – the forthcoming economic challenges for a developing country. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V., Padhy S.K. Mental health among COVID-19 survivors: Are we overlooking the biological links? Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V., Subramanian K., Selvakumar N., Kattimani S. Suicide prevention strategies: an overview of current evidence and best practice elements. Int. J. Adv. Med. Health Res. 2018;5:43. doi: 10.4103/IJAMR.IJAMR_71_18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- News18 India . News18; 2020. Migrant Worker from Assam Commits Suicide in Surat [WWW Document] URL https://www.news18.com/news/india/migrant-worker-from-assam-commits-suicide-in-surat-2628969.html (Accessed 6.19.20) [Google Scholar]

- Okusaga O., Yolken R.H., Langenberg P., Lapidus M., Arling T.A., Dickerson F.B., Scrandis D.A., Severance E., Cabassa J.A., Balis T., Postolache T.T. Association of seropositivity for influenza and coronaviruses with history of mood disorders and suicide attempts. J. Affect. Disord. 2011;130:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satici B., Saricali M., Satici S.A., Griffiths M.D. Intolerance of uncertainty and mental wellbeing: serial mediation by rumination and fear of COVID-19. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00305-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon R. COVID-19 and mental health: preserving humanity, maintaining sanity, and promoting health. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;51 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalsman G., Hawton K., Wasserman D., van Heeringen K., Arensman E., Sarchiapone M., Carli V., Höschl C., Barzilay R., Balazs J., Purebl G., Kahn J.P., Sáiz P.A., Lipsicas C.B., Bobes J., Cozman D., Hegerl U., Zohar J. Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:646–659. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]