Abstract

Objective

To determine how state guidance documents address equity concerns in K-12 schools during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.

Study design

Using online searches, we collected state-level documents from all 50 states and the District of Columbia discussing reopening plans for K-12 schools in the 2020-2021 academic year. We examined whether these documents explicitly mentioned equity as a concern, as well as if and how they addressed the following equity issues: food insecurity and child nutrition, homelessness or temporary housing, lack of access to Internet/technology, students with disabilities or special needs, English-language learners, students involved with or on the verge of involvement with the Department of Children and Family Services or an equivalent agency, mental health support, students/staff at greater risk of severe illness from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, and students/staff living with someone at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Results

Forty-four of 51 states (86%) explicitly mentioned equity as a concern or guiding principle. At least 90% of states offered guidance for 7 equity issues. Fewer than 75% of states addressed homelessness or temporary housing, students involved with or on the verge of involvement with Department of Children and Family Services or an equivalent agency, and students/staff living with someone at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Conclusions

Wide variability exists in state-level guidance to help K-12 schools develop reopening plans that protect those who are most vulnerable to learning loss or reduced access to basic needs. Interpretation and implementation by local educational agencies will need to be assessed.

Keywords: equity, states, schools, COVID-19, pandemic

Abbreviations: COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

As part of the attempt to reduce transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and control the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, schools closed across the globe in February-March 2020. In the US alone, more than 55 million children have missed in-class instruction.1 Worldwide, schools have closed in more than 190 countries, affecting 1.57 billion children and youth, or 90% of the world's student population.2 When and how to reopen schools has been a difficult and sensitive topic on a national, regional, and local level. Despite uncertainties regarding the future of the pandemic, the American Academy of Pediatrics has released guidelines stating that it “strongly advocates” the goal of “having students physically present in school,” citing evidence that children and adolescents are less likely to be symptomatic, to have severe disease resulting from SARS-CoV-2 infection, and to spread infection.3

Research has challenged the last of these points. A large study from South Korea showed that children between the ages of 10 and 19 years can spread the virus at least as well as adults,4 and another study found that children younger than 5 years of age with mild-to-moderate symptoms may have high amounts of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in their nasopharynx compared with older children and adults.5 At least 338 000 children in the US have tested positive through July 30, 2020.6 Regardless of differences in transmission potential between children and adults, it is increasingly evident that school re-entry can increase virus levels within a community.

However, long-term school closures can negatively impact students, especially those who come from disadvantaged backgrounds. Students from low-income families may lack access to a household computer, resulting in significant learning loss relative to their peers during periods of remote instruction. Without reliable access to free and reduced-cost meals, these students might also not have enough to eat. At the end of April 2020, more than 1 in 5 households in the US and 2 in 5 households with mothers with children 12 years and younger were food insecure. Furthermore, these rates of food insecurity were meaningfully greater than at any other previous point for which there are comparable data.7 Many parents whose jobs cannot be done from home also rely on schools as a source of childcare.

Beyond delivering academic instruction, schools provide students with a source of nutrition, as well as opportunities for socialization and physical activity. They are sites for physical, speech, and mental health therapy. For some students, they are also a precious source of safety. School closures may inhibit the reporting of child abuse. Using data from Florida, the number of reported child maltreatment allegations was approximately 27% lower than expected during March and April 2020, the first 2 months in which schools were closed in Florida.8 At the same time, child sexual abuse may have increased following lockdown orders. At the end of March 2020, the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network reported that for the first time ever, one-half of the victims receiving help from the National Sexual Assault Hotline were minors.9 Of minors who discussed coronavirus-related concerns, 79% stated that they were currently living with their abuser.9

Balancing these types of equity concerns with the safety concerns associated with viral transmission will be the key challenge to overcome during this school year.10 In the spring and summer months leading up to school restart dates, each of the 50 states, as well as Washington, DC, produced its own K-12 school reopening guidelines. Our aim was to compare these guidelines, focusing on how they intend to address equity concerns relevant to the students and staff who are especially vulnerable during this time. The results may be informative for state and local educational agencies as they continue to revise and finalize their plans for the 2020-2021 academic year.

Methods

We conducted Google searches to identify state-level documents from 50 states and the District of Columbia discussing the reopening of K-12 schools in the 2020-2021 academic year. For convenience, we will refer to DC as our “51st state.” Searches included various combinations of the following terms: [name of state], school, K-12, education, department of education, department of public health, COVID-19, reopening, guidelines, and plan. We used the most recent guidelines as of July 15, 2020, in our assessment, although we expect schools to continue to update their plans as the year progresses.

For each state-level document, we extracted the state, author, and date last updated as of our reading. We also recorded whether the document mentioned equity as a guiding principle and whether the state offered any specific guidance regarding the following equity concerns: (1) food insecurity and child nutrition, (2) homelessness or temporary housing, (3) lack of access to Internet/technology, (4) students with disabilities or special needs in education, (5) English-language learners, (6) students involved with or on the verge of involvement with the Department of Children and Family Services or an equivalent agency (this category includes students at risk of abuse and neglect, as well as students in foster care), (7) mental health support, (8) students at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection, (9) staff at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection, (10) students living with someone at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection, and (11) staff living with someone at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection. More information about how we defined each of these 11 categories can be found in Table I (available at www.jpeds.com). All documents were read by the same researcher, 1 researcher read all state documents and 2 other researchers read a subset of state documents (19 in total) to confirm data extraction. All disagreements were resolved through discussion.

After extracting data from each state document, we determined what proportion of documents overall mentioned equity as a consideration when planning for the upcoming academic year. We then determined what proportion of documents contained guidance for each of the 11 aforementioned equity issues. To identify examples of how these equity-related policies are being considered at the local level, we also compared school reopening guidelines from 4 major cities in 2 randomly chosen states to their respective state documents.

Using data from all 51 states, we examined relationships between the degree of equity guidance and a state's political affiliation, poverty rates, percent urbanization, Gini coefficient (a measure of income inequality), educational attainment, and health score as defined by the United Health Foundation. Lastly, we compiled guidelines in aggregate to identify how states are planning to address concerns of equity in the coming academic year.

Results

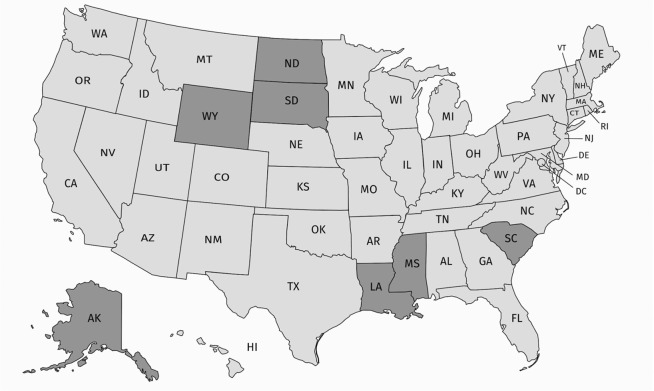

In our review of planning documents, we found that 44 of 51 states (86%) explicitly mentioned equity as a concern or guiding principle. The 7 states that did not mention equity included states from the West, Midwest, and Southeast regions of the US (Figure 1 ). On average, states addressed 8.6 of 11 equity issues. Despite lacking an explicit mention of equity, 2 states—North Dakota and South Carolina—performed above this average, mentioning 10 and 11 equity concerns, respectively. The remaining states—Alaska, Mississippi, South Dakota, Louisiana, and Wyoming—offered guidance for a range of 4 to 7 concerns (Table II [available at www.jpeds.com]11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61 shows equity concerns mentioned by each state).

Figure 1.

States with planning documents that did not explicitly mention equity as a concern or guiding principle. Dark gray = did not explicitly mention equity; Light gray = did explicitly mention equity.

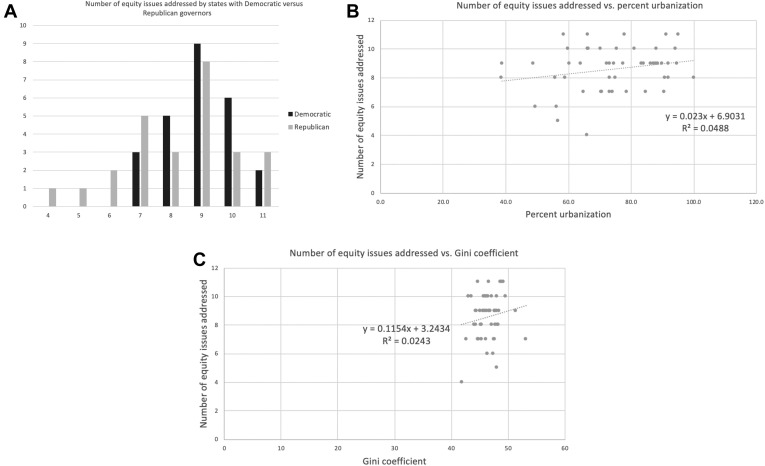

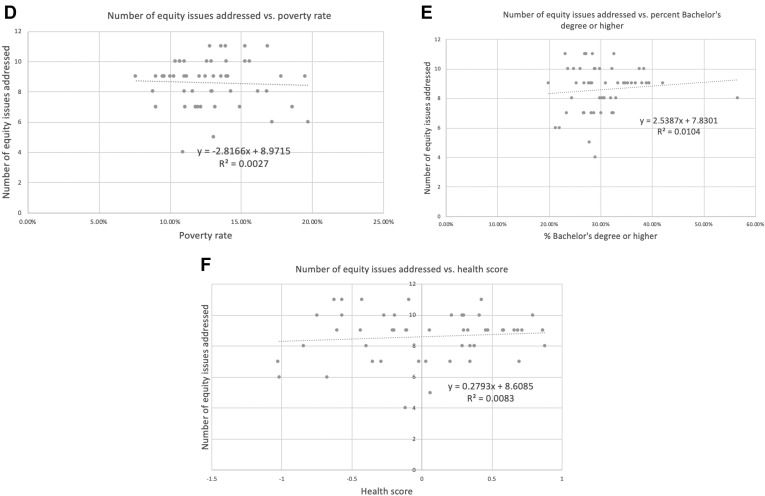

Although 6 of the 7 states that did not explicitly mention equity as a guiding principle have Republican governors, no significant difference was found between the total number of equity issues addressed for states with Republican vs Democratic leaders (P = .11) (Figure 2, A; available at www.jpeds.com).62 In addition, we found no strong correlation between the number of equity issues addressed and a state's poverty rate, urbanization level, Gini coefficient, educational attainment, or health score as defined by the United Health Foundation (Figure 2, B-F; available at www.jpeds.com).63, 64, 65, 66, 67

Figure 2.

Factors that potentially affect a state's attention to equity: political affiliation, percent urbanization, Gini coefficient (a measure of income inequality), poverty rate, educational attainment, and overall health score (as defined by the United Health Foundation). A, Histogram comparing the distribution of equity issues addressed for states with Republican vs Democratic leaders (P = .11).62B, Linear regression comparing the number of equity issues addressed and a state's percent urbanization (R2 = 0.05).63C, Linear regression comparing the number of equity issues addressed and a state's Gini coefficient (R2 = 0.02).64D, Linear regression comparing the number of equity issues addressed and a state's poverty rate (R2 = 0.003).65E, Linear regression comparing the number of equity issues addressed and what percentage of a state's population holds a bachelor's degree or greater (R2 = 0.01).66F, Linear regression comparing the number of equity issues addressed and state health score as defined by the United Health Foundation (R2 = 0.01).67 This score was calculated using 35 measures representing 5 categories: behaviors, social and economic factors, physical environment, clinical care, and health outcomes. A score of 0 represents the health score of the US. No score was available for DC.

Table III shows what proportion of states addressed each of our 11 categories. Overall, states performed well, and we found that 7 of our equity concerns were addressed by at least 90% of all states. The remaining 4 were addressed by fewer than 75% of all states and include homelessness or temporary housing, students involved with or on the verge of involvement with the Department of Children and Family Services or an equivalent agency, students living with someone at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection, and staff living with someone at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Table III.

Proportion of state government plans with guidance on specific equity concerns, listed in descending order

| Equity concerns | Number of documents with policies addressing this group or issue |

|---|---|

| Students with disabilities or special needs | 50 (98%) |

| Students at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection | 50 (98%) |

| Mental health support | 49 (96%) |

| Food insecurity and child nutrition | 48 (94%) |

| Lack of access to Internet/technology | 48 (94%) |

| Staff at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection | 47 (92%) |

| English-language learners | 46 (90%) |

| Homelessness, temporary housing | 36 (71%) |

| Students involved with or on the verge of involvement with the DCFS or equivalent agency | 31 (61%) |

| Students living with someone at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection | 27 (53%) |

| Staff living with someone at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection | 7 (14%) |

We randomly selected California and Mississippi when comparing equity issues addressed by city-level vs state-level documents. Based on a reading of school reopening guidelines for a sample of cities in California (San Francisco, Sacramento, San Diego, and Los Angeles)68, 69, 70, 71 and Mississippi (Jackson, Gulfport, Vicksburg, and Biloxi),72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80 city-level guidance addressed the same or fewer equity issues when compared to the corresponding state-level guidance.

Table IV contains a summary of best practices for each of our equity concerns based on data from all 51 states.

Table IV.

Summary of best practices for addressing equity concerns in K-12 education

| Equity concerns | Guidelines |

|---|---|

| Food insecurity and child nutrition |

|

| Homelessness or temporary housing |

|

| Lack of access to Internet or technology |

|

| Students with disabilities or special needs |

|

| English-language learners |

|

| Students involved with or on the verge of involvement with DCFS or equivalent agency |

|

| Mental health support |

|

| Students at greater risk, or living with someone at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection |

|

| Staff at greater risk, or living with someone at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection |

|

HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996; PPE, personal protective equipment; USDA, US Department of Agriculture.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted the education and well-being of schoolchildren across the US. The most at-risk students include those from low-income families, students with disabilities, English-language learners, students at risk of abuse or neglect, and students with underlying medical conditions, among other groups. Some individuals may identify with more than 1 of these groups, along with historically marginalized groups such as racial and ethnic minorities, refugees, and LGBTQ + individuals, placing them at even greater risk of experiencing learning loss or lacking basic needs during this time. Teachers and staff members face their own challenges related to operating schools during an ongoing pandemic; many are worried about their safety if schools open in person and about how best to teach and support students if schools continue online.81

In acknowledgment of all of these challenges, most states have made equity a guiding principle in drafting guidelines for the 2020-2021 academic year. Our study revealed that almost all states offer guidance for schools regarding food insecurity, lack of access to Internet/technology, students with disabilities, English-language learners, mental health support, and students or staff at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Some states may need to further consider how they can support students experiencing homelessness or temporary housing, students at risk of abuse or neglect, students in foster care, and students or staff living with individuals at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

We were unable to find a factor that strongly correlated with the total number of equity issues that a state's guidelines addressed. In particular, the lack of correlation between income inequality, educational attainment, health scores, or poverty rates and the degree of equity guidance suggests that state-level planning committees may be crafting K-12 school equity guidelines independently of state-level measures of inequity.

Different equity concerns may be of greater importance depending on whether schools are providing in-person instruction or distance learning. For instance, under distance learning, schools may not need to provide special support for individuals with underlying medical conditions, but they will need to devote greater efforts to supporting students without Internet access, as well as students who rely on schools for free- or reduced-cost meals. They will also need to develop practices that enable teachers to identify signs of abuse or neglect, despite only encountering students in a remote learning environment. Regardless of whether schools are opening in-person or not, continuous collaboration among families, teachers, school leaders, public health officials, and community organizations will be essential to achieving a balance of safety and equity in the coming academic year.

Our study has several limitations. First, we only reviewed publicly available guidance documents posted by state-level departments online. Certain states may have prepared relevant guidance documents that were not posted on the Internet and, as a result, were not represented in our data. As the pandemic continues to evolve, some states have modified their guidelines and their plans for reopening, but changes and addendum guidance documents added after July 15, 2020 were not included here. Readers looking for continuous updates may consider Johns Hopkins University's online eSchools + Initiative, which presents a regularly updated analysis of school reopening plans.82 However, our study and the eSchools + Initiative used different frameworks. For instance, the eSchools + Initiative included broader categories such as “children of poverty and systemic disadvantage,” and we considered 3 separate poverty-related issues: food insecurity, homelessness, and lack of access to Internet or technology. The eSchools + Initiative also included categories not specific to vulnerable populations, including “privacy” and “engagement and transparency.” In general, relative to our study, the eSchools + Initiative offers a broader overview of school reopening guidance while focusing less on compiling the specific equity-related practices proposed by different state guidelines.83

A second limitation of our study is that local educational agencies may or may not follow state-level guidance. We examined this possibility when reading policies from cities in Mississippi and California. In this sample, city-level guidance did not conflict with the equity concerns raised by state-level documents. However, some local officials have announced an intent to depart from regional or state-level recommendations regarding school reopening; these local officials include leaders of private schools, which do not share many of the same regulations governing public school systems.84 Even at the local level, discrepancies might arise between stated guidance and implementation as schools begin the academic year. For instance, local educational agencies may intend to secure funding for technological devices to assist students in need, but this funding may not be available.

Third, our data extraction does not reflect differences in the comprehensiveness of state guidelines. Some state provided detailed guidance for a particular equity concern, whereas others only mentioned that a particular concern should be addressed. Policies with minimal guidance leave local educational agencies with the responsibility of figuring out how to support their students and staff in at-risk populations.

This review of state government guidance focused exclusively on equity concerns in K-12 schools during the COVID-19 pandemic. School leaders can use the findings presented here to identify best practices for a variety of equity concerns. Implementing some or all of these practices will help protect vulnerable populations in the 2020-2021 academic year.

Data Statement

Data sharing statement available at www.jpeds.com.

Footnotes

Supported by the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine Summer Research Program and the University of Chicago Bucksbaum Institute for Clinical Excellence [to A.L.]. L.F.R. serves on the Editorial Board of The Journal of Pediatrics.

Supplementary Data

Appendix

Table I.

Coding guidelines used in data extraction

| Category (Y/N) | Coding guidelines |

|---|---|

| Mentions equity as a guiding principle | Check Y if any of the following:

|

| Food insecurity and child nutrition | Check Y if guidance mentions policies relevant to food insecurity

|

| Homelessness or temporary housing | Check Y if guidance mentions students experiencing homelessness or addresses this population's needs

|

| Lack of access to Internet/technology | Check Y if guidance mentions students without access to Internet/technology or addresses this population's needs

|

| Students with disabilities or special needs | Check Y if guidance mentions this population

|

| English-language learners | Check Y if guidance mentions this population

|

| Students involved with or on the verge of involvement with DCFS or equivalent agency | Check Y if guidance mentions this population (including students placed in foster care, OR students at greater risk of abuse and neglect), OR if guidance mentions DCFS or an equivalent agency

|

| Mental health support | Check Y if guidance mentions mental health resources for students OR staff

|

| Students at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection | Check Y if guidance mentions this population

|

| Staff at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection | Check Y if guidance mentions this population

|

| Students living with someone at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection | Check Y if guidance mentions this population. States that mentioned allowing families to self-report as being high risk were also marked Y

|

| Staff living with someone at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection | Check Y if guidance mentions this population

|

DCFS, Department of Children and Family Services; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Table II.

Equity issues mentioned by each state

| States | Author | Date last updated (or, if unknown, date accessed) | Mentions equity as a guiding principle, Y/N | Child nutrition and food insecurity, Y/N | Homelessness, temporary housing, Y/N | Lack of access to internet/technology, Y/N | Students with disabilities/special needs, Y/N | English-language learners, Y/N | Students involved with or on the verge of involvement with DCFS, Y/N | Mental health support for students or staff, Y/N | Students at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection, Y/N | Staff at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection, Y/N | Student living with someone at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection, Y/N | Staff living with someone at greater risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection, Y/N | Total (out of 11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL11 | AL State Department of Education | June 26, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 8 |

| AK12 | AK Department of Education and Early Development, AK Department of Health and Social Services | July 15, 2020 | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | 4 |

| AZ13 | AZ Department of Education | June 1, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 9 |

| AR14 | AR Department of Education | June 16, 2020 | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 6 |

| CA15 | CA Department of Education | June 8, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 11 |

| CO16 | CO Department of Education | June 22, 2020 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 9 |

| CT17 | CT State Department of Education | June 29, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 10 |

| DE18 | DE Department of Education | July 9, 2020 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 9 |

| FL19 | FL Department of Education | June 11, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 11 |

| GA20 | GA Department of Education and GA Department of Public Health | July 11, 2020 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 8 |

| HI21 | HI State Department of Education | July 8, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | 8 |

| ID22 | ID Department of Education, ID Department of Health & Welfare, ID State Board of Education | July 9, 2020 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 7 |

| IL23 | IL State Board of Education, IL Department of Public Health | June 23, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | 9 |

| IN24 | IN Department of Education | July 15, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 9 |

| IA25 | IA Department of Education | July 15, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 9 |

| KS26 | KS State Department of Education | July 15, 2020 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 7 |

| KY27 | KY Department of Education | July 13, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 11 |

| LA28 | LA Department of Education | July 15, 2020 | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 7 |

| ME29 | ME Department of Education | July 13, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 8 |

| MD30 | MD State Department of Education | June 26, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 9 |

| MA31 | MA Department of Elementary and Secondary Education | July 15, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 9 |

| MI32 | MI Return to School Advisory Council | June 30, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 9 |

| MN33 | MN Department of Education, MN Department of Health | June 18, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 9 |

| MS34 | MS Department of Education | June 8, 2020 | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 6 |

| MO35 | MO School Boards' Association | July 9, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | 7 |

| MT36 | MT Office of Public Instruction | July 2, 2020 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 |

| NE37 | NE Department of Education | July 15, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 8 |

| NV38 | NV Department of Education | June 9, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 10 |

| NH39 | NH Department of Education | July 15, 2020 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 9 |

| NJ40 | NJ Department of Education | June 26, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 9 |

| NM41 | NM Public Education Department | June 20, 2020 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| NY42 | NY State Education Department, NY State Department of Health | July 13, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 9 |

| NC43 | NC State Board of Education, NC Department of Public Instruction | July 15, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 10 |

| ND44 | ND Department of Public Instruction | July 15, 2020 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 10 |

| OH45 | OH Department of Education | July 9, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 11 |

| OK46 | OK State Department of Education | June 3, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 10 |

| OR47 | OR Department of Education, OR Health Authority | June 30, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 10 |

| PA48 | PA Department of Education | June 26, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 7 |

| RI49 | RI Department of Education | June 19, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 8 |

| SC50 | SC Department of Education | June 22, 2020 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 11 |

| SD51 | SD Department of Education | July 13, 2020 | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 5 |

| TN52 | TN Department of Education | July 15, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 10 |

| TX53 | TX Education Agency | July 2, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | 7 |

| UT54 | UT State Board of Education | June 26, 2020 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 7 |

| VT55 | VT Agency of Education | July 15, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 9 |

| VA56 | VA Department of Education | July 1, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 10 |

| WA57 | WA Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction | July 8, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 9 |

| WV58 | WV Department of Education | July 15, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 9 |

| WI59 | WI Department of Public Instruction | June 29, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 10 |

| WY60 | WY Department of Education | July 1, 2020 | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | 7 |

| DC61 | DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education | July 13, 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 8 |

Y indicates that guidance was found for a particular issue; N indicates that guidance was not found.

References

- 1.Map: Coronavirus and School Closures - Education Week [Internet]. 2020. https://www.edweek.org/ew/section/multimedia/map-coronavirus-and-school-closures.html Accessed June 30, 2020.

- 2.Giannini S., Jenkins R., Saavedra J. 2020. Reopening schools: When, where and how? [Internet]. UNESCO.https://en.unesco.org/news/reopening-schools-when-where-and-how Accessed August 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Pediatrics COVID-19 Planning Considerations: Guidance for School Re-entry [Internet] http://services.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/clinical-guidance/covid-19-planning-considerations-return-to-in-person-education-in-schools/ Accessed August 10, 2020.

- 4.Park Y.J., Choe Y.J., Park O., Park S.Y., Kim Y.-M., Kim J. Early release–contact tracing during coronavirus disease outbreak, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.3201/eid2610.201315. 26(10) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heald-Sargent T., Muller W.J., Zheng X., Rippe J., Patel A.B., Kociolek L.K. Age-related differences in nasopharyngeal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) levels in patients with mild to moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Pediatr. 2020:e203651. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Academy of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital Association . 2020. AAP and CHA - Children and COVID-19 State Data Report [Internet]https://downloads.aap.org/AAP/PDF/AAP%20and%20CHA%20-%20Children%20and%20COVID-19%20State%20Data%20Report%207.30.20%20FINAL.pdf Accessed August 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauer L. 2020. The COVID-19 crisis has already left too many children hungry in America [Internet]. Brookings.https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/05/06/the-covid-19-crisis-has-already-left-too-many-children-hungry-in-america/ Accessed June 30, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baron E.J., Goldstein E.G., Wallace C.T. Suffering in silence: how COVID-19 school closures inhibit the reporting of child maltreatment. J Public Econ. 2020;190:104258. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network . 2020. For the First Time Ever, Minors Make Up Half of Visitors to National Sexual Assault Hotline [Internet]. RAINN.https://www.rainn.org/news/first-time-ever-minors-make-half-visitors-national-sexual-assault-hotline Accessed August 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faden R., Faxon E., Anderson A., Wahl M., Collins M. 2020. The Ethics of K-12 School Reopening: Identifying and Addressing the Values at Stake. Johns Hopkins University.https://equityschoolplus.jhu.edu/files/ethics-of-k12-school-reopening-identifying-and-addressing-the-values-at-stake.pdf Accessed August 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alabama State Department of Education . 2020. Roadmap for Reopening Schools.https://www.alsde.edu/Documents/Roadmap%20for%20Reopening%20Schools%20June%2026%202020.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alaska Department of Education and Early Development, Alaska Department of Health and Social Services . 2020. Alaska Smart Start 2020 Framework Guidance for K-12 Schools.https://education.alaska.gov/news/COVID-19/Alaska%20Smart%20Start%202020%20Framework%20Guidance.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arizona Department of Education COVID-19: Guidance and Suggestions [Internet] https://www.azed.gov/communications/2020/03/10/guidance-to-schools-on-covid-19/ Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 14.Arkansas Department of Education . 2020. Arkansas Ready for Learning.http://dese.ade.arkansas.gov/public/userfiles/Communications/Ready/Arkansas_Ready_for_Learning_Final_7_8_20_V3.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.California Department of Education . 2020. Stronger Together: A Guidebook for the Safe Reopening of California’s Public Schools.https://www.cde.ca.gov/ls/he/hn/documents/strongertogether.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colorado Department of Education Planning for the 2020-21 School Year: A Framework and Toolkit for School and District Leaders [Internet] https://www.cde.state.co.us/planning20-21 Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 17.Connecticut State Department of Education . 2020. Adapt, Advance, Achieve: Connecticut’s Plan to Learn and Grow Together.https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/SDE/COVID-19/CTReopeningSchools.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delaware Department of Education . 2020. Returning to School.https://www.doe.k12.de.us/cms/lib/DE01922744/Centricity/Domain/599/ddoe_returningtoschool_guidance_final.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Florida Department of Education . 2020. Reopening Florida’ Schools and the CARES Act.http://www.fldoe.org/core/fileparse.php/19861/urlt/FLDOEReopeningCARESAct.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Georgia Department of Education, Georgia Department of Public Health Georgia’s Path to Recovery for K-12 Schools [Internet]. Georgia Insights—Data. Access. Action. | An initiative of the Georgia Department of Education. https://www.georgiainsights.com/recovery.html Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 21.Hawaii State Department of Education Return to Learn [Internet] http://www.hawaiipublicschools.org/ConnectWithUs/MediaRoom/PressReleases/Pages/school-year-2020-21.aspx Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 22.Idaho Department of Education, Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, Idaho State Board of Education . 2020. Idaho Back to School Framework.https://www.sde.idaho.gov/re-opening/files/Idaho-Back-to-School-Framework-2020.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Illinois State Board of Education, Illinois Department of Public Health . 2020. Starting the 2020-21 School Year.https://www.isbe.net/Documents/Part-3-Transition-Planning-Phase-4.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Indiana Department of Education Re-entry Resources [Internet] https://www.doe.in.gov/covid-19/re-entry-resources Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 25.Iowa Department of Education Return-to-Learn [Internet] https://sites.google.com/iowa.gov/returntolearn/home Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 26.Kansas State Department of Education Navigating Change: Kansas’ Guide to Learning and School Safety Operations [Internet] https://www.ksde.org/Teaching-Learning/Resources/Navigating-Change-Kansas-Guide-to-Learning-and-School-Safety-Operations Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 27.Kentucky Department of Education COVID-19 Reopening Resources [Internet] https://education.ky.gov/comm/Pages/COVID-19-Reopening-Resources.aspx Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 28.Louisiana Department of Education . 2020. School Reopening Guidelines and Resources.https://www.louisianabelieves.com/docs/default-source/strong-start-2020/school-reopening-guidelines-and-resources.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maine Department of Education Framework for Returning to Classroom Instruction [Internet] https://www.maine.gov/doe/framework Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 30.Maryland State Department of Education . 2020. Maryland Together: Maryland’s Recovery Plan for Education.http://marylandpublicschools.org/newsroom/Documents/MSDERecoveryPlan.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Coronavirus/COVID-19: Guidance/On the Desktop Messages [Internet] http://www.doe.mass.edu/covid19/on-desktop.html Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 32.Michigan Return to School Advisory Council MI Safe Schools: Michigan’s 2020-21 Return to School Roadmap. 2020. https://www.michigan.gov/documents/whitmer/MI_Safe_Schools_Roadmap_FINAL_695392_7.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 33.Minnesota Department of Education, Minnesota Department of Public Health . 2020. Guidance for Minnesota Public Schools: 2020-21 School Year Planning.https://education.mn.gov/MDE/index.html Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mississippi Department of Education . 2020. Considerations for Reopening Mississippi Schools.https://msachieves.mdek12.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Considerations-for-Reopening-Schools-June-8-FINAL.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Missouri School Boards’ Association . 2020. Pandemic Recovery Considerations: Re-Entry and Reopening of Schools.https://ams.embr.mobi/Documents/DocumentAttachment.aspx?C=ZfON&DID=GJGDM Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montana Office of Public Instruction . 2020. Reopening MT Schools Guidance.http://opi.mt.gov/Portals/182/COVID-19/Reopening%20MT%20Schools%20Guidance-Final.pdf?ver=2020-07-02-114033-897 Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nebraska Department of Education Launch Nebraska [Internet] https://www.launchne.com/ Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 38.Nevada Department of Education . 2020. Nevada’s Path Forward.https://nvhealthresponse.nv.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Nevada_Path_Forward_6.9.20_FRAMEWORK.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39.New Hampshire Department of Education New Hampshire Grades K-12 Back-to-School Guidance. https://www.covidguidance.nh.gov/sites/g/files/ehbemt381/files/inline-documents/sonh/k-12-back-to-school.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 40.State of New Jersey Department of Education . 2020. The Road Back: Restart and Recovery Plan for Education.https://www.nj.gov/education/reopening/NJDOETheRoadBack.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 41.New Mexico Public Education Department . 2020. Reentry Guidance.https://webnew.ped.state.nm.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/20NMPED_ReentryGuide_Hybrid.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42.New York State Education Department . 2020. Recovering, Rebuilding, and Renewing the Spirit of Our Schools School Reopening Guidance.http://www.nysed.gov/common/nysed/files/programs/reopening-schools/nys-p12-school-reopening-guidance.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 43.North Carolina State Board of Education North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. Lighting Our Way Forward: North Carolina’s Guidebook for Reopening Public Schools. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1z5Mp2XzOOPkBYN4YvROz4YOyNIF2UoWq9EZfrjvN4x8/preview?pru=AAABcsinN5A41035PyhCjNNDQ5i3_9e2w Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 44.North Dakota Department of Public Instruction North Dakota K-12 Smart Restart Fall 2020. https://www.nd.gov/dpi/sites/www/files/documents/Covid-19/NDK12restartguide.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 45.Ohio Department of Education . 2020. Planning Guide for Ohio Schools and Districts.http://education.ohio.gov/getattachment/Topics/Reset-and-Restart/Reset-Restart-Guide.pdf.aspx?lang=en-US Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oklahoma Department of Education . 2020. Return to Learn Oklahoma.https://sde.ok.gov/sites/default/files/Return%20to%20Learn%20Oklahoma.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oregon Department of Education, Oregon Health Authority . 2020. Ready Schools, Safe Learners 2020-21 Guidance.https://www.oregon.gov/ode/students-and-family/healthsafety/Documents/Ready%20Schools%20Safe%20Learners%202020-21%20Guidance.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pennsylvania Department of Education Reopening Guidance for the 2020-21 School Year [Internet] https://www.education.pa.gov/Schools/safeschools/emergencyplanning/COVID-19/SchoolReopeningGuidance/Pages/default.aspx [cited 2020 Jul 15] Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 49.State of Rhode Island . 2020. Back_to_School_RI_Guidance_6.19.20-2.pdf.https://www.ride.ri.gov/Portals/0/Uploads/Documents/COVID19/Back_to_School_RI_Guidance_6.19.20.pdf?ver=2020-06-19-120036-393 Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 50.South Carolina Department of Education . 2020. Guidance and Recommendations for 2020-21 School Year.https://ed.sc.gov/newsroom/covid-19-coronavirus-and-south-carolina-schools/accelerateed-task-force/draft-accelerateed-task-force-guidance-and-recommendations-for-2020-21-school-year/ Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 51.South Dakota Department of Education Starting Well 2020 [Internet] https://doe.sd.gov/coronavirus/startingwell.aspx Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 52.Tennessee Department of Education Reopening Guidance [Internet] https://www.tn.gov/education/health-and-safety/update-on-coronavirus/reopening-guidance.html Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 53.Texas Education Agency Coronavirus (COVID-19) Support and Guidance [Internet]. Texas Education Agency. https://tea.texas.gov/texas-schools/health-safety-discipline/covid/coronavirus-covid-19-support-and-guidance Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 54.Utah State Board of Education . 2020. School Reopening Planning Handbook.https://schools.utah.gov/file/5997f53e-85ca-4186-83fe-932385ea760a Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 55.State of Vermont Agency of Education COVID-19 Guidance for Vermont Schools [Internet] https://education.vermont.gov/covid19#shs Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 56.Virginia Department of Education . 2020. Recover Redesign Restart.http://www.doe.virginia.gov/support/health_medical/covid-19/recover-redesign-restart-2020.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction . 2020. Reopening Washington Schools 2020: District Planning Guide.https://www.k12.wa.us/sites/default/files/public/workgroups/Reopening%20Washington%20Schools%202020%20Planning%20Guide.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 58.West Virginia Department of Education West Virginia School System Re-entry and Recovery Guidance [Internet]. West Virginia Department of Education. https://wvde.us/school-system-re-entry/ Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 59.Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction . 2020. Education Forward: Reopening Wisconsin Schools.https://dpi.wi.gov/sites/default/files/imce/sspw/pdf/Education_Forward_web.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wyoming Department of Education . 2020. Smart Start Working Document.https://1ddlxtt2jowkvs672myo6z14-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Smart-Start-Guidance.pdf Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 61.DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education Guidance and Resources for COVID-19-related Closures and Recovery [Internet] https://osse.dc.gov/page/guidance-and-resources-covid-19-related-closures-and-recovery Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 62.Partisan composition of governors [Internet]. Ballotpedia. https://ballotpedia.org/Partisan_composition_of_governors Accessed August 7, 2020.

- 63.U.S. Census Bureau Urban Percentage of the Population for States, Historical | Iowa Community Indicators Program [Internet] https://www.icip.iastate.edu/tables/population/urban-pct-states Accessed August 7, 2020.

- 64.Population Reference Bureau U.S. Indicators: Gini Index of Income Inequality - PRB [Internet] https://www.prb.org/usdata/ Accessed August 7, 2020.

- 65.List of U.S. states and territories by poverty rate. In: Wikipedia [Internet] 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_U.S._states_and_territories_by_poverty_rate&oldid=966056135 Accessed August 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 66.List of U.S. states and territories by educational attainment. In: Wikipedia [Internet] 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_U.S._states_and_territories_by_educational_attainment&oldid=965165403 Accessed August 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 67.United Health Foundation Findings State Rankings | 2018 Annual Report [Internet]. America’s Health Rankings. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/learn/reports/2018-annual-report/findings-state-rankings Accessed August 7, 2020.

- 68.San Francisco Department of Public Health Interim guidance released to help plan safer reopening of local schools | San Francisco [Internet] https://sf.gov/news/interim-guidance-released-help-plan-safer-reopening-local-schools Accessed July 27, 2020.

- 69.Sacramento City Unified School District. COVID-19 [Internet]. Sacramento City Unified School District. https://www.scusd.edu/covid-19 Accessed July 27, 2020.

- 70.San Diego Unified School District. COVID-19 INFORMATION [Internet] https://sites.google.com/sandi.net/covid19 Accessed July 27, 2020.

- 71.Los Angeles County Office of Education COVID-19 Resources [Internet] https://www.lacoe.edu/Home/Health-and-Safety/Coronavirus-Resources Accessed July 27, 2020.

- 72.Jackson Public Schools Coronavirus Response [Internet] http://www.jackson.k12.ms.us%2Fsite%2Fdefault.aspx%3FPageID%3D11454 Accessed August 7, 2020.

- 73.Gulfport School District . 2020. Reopening Schools in the Wake of the COVID-19 Pandemic Contingency Plan.https://www.gulfportschools.org/cms/lib/MS01910520/Centricity/Domain/17/Letter%20to%20Parents%20-%20FINAL.pdf Accessed August 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gulfport School District . 2020. GSD Returning to School: Questions and Answers.https://www.gulfportschools.org/cms/lib/MS01910520/Centricity/Domain/9/GSD-Returning%20to%20School%202020-21.pdf Accessed August 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gulfport School District Virtual Learning Program - Schedules, Guidelines, and Expectations. https://www.gulfportschools.org/site/handlers/filedownload.ashx?moduleinstanceid=29337&dataid=45068&FileName=GSD%20Virtual%20Learning%20Student%20Guidelines.pdf Accessed August 7, 2020.

- 76.Vicksburg Warren School District Guide for the Reopening of Schools. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ZFozNleX5pmh7x6OIPEEd_6m3sy8rWCA/view Accessed August 7, 2020.

- 77.Biloxi Public Schools Ways to Prepare for Returning to School. https://www.biloxischools.net/site/default.aspx?PageType=3&DomainID=4&ModuleInstanceID=142&ViewID=6446EE88-D30C-497E-9316-3F8874B3E108&RenderLoc=0&FlexDataID=14798&PageID=1 Accessed August 7, 2020.

- 78.Biloxi Public Schools 2020-21 Return To School Plan. https://www.biloxischools.net/site/default.aspx?PageType=3&DomainID=4&ModuleInstanceID=142&ViewID=6446EE88-D30C-497E-9316-3F8874B3E108&RenderLoc=0&FlexDataID=14485&PageID=1 Accessed August 7, 2020.

- 79.Biloxi Public Schools Transportation & Mask Information. https://www.biloxischools.net/site/default.aspx?PageType=3&DomainID=4&ModuleInstanceID=142&ViewID=6446EE88-D30C-497E-9316-3F8874B3E108&RenderLoc=0&FlexDataID=14617&PageID=1 Accessed August 7, 2020.

- 80.Boudreaux M. 2020. Biloxi return to school.https://www.biloxischools.net/cms/lib/MS01910473/Centricity/Domain/4/2020-21%20School%20Plan%20letter.pdf Accessed August 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Most Teachers Concerned About In-Person School 2 In 3 Want To Start The Year Online [Internet]. NPR.org. 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/08/06/898584176/most-teachers-concerned-about-in-person-school-2-in-3-want-to-start-the-year-onl Accessed August 10, 2020.

- 82.Johns Hopkins University . 2020. eSchool+ School Reopening Policy Tracker [Internet]https://equityschoolplus.jhu.edu/reopening-policy-tracker/ Accessed August 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Addressing Disparities in K-12 Education During the Pandemic: Examples of Policy Options and Guidance [Internet]. Johns Hopkins University. 2020. https://equityschoolplus.jhu.edu/files/addressing-disparities-in-k12-education-during-the-pandemic-examples-of-policy-options.pdf Accessed August 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Romero S., Rio del GMN, Mazzei P. If Public Schools Are Closed, Should Private Schools Have to Follow? - The New York Times [Internet]. 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/05/us/schools-reopening-private-public.html Accessed August 10, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.