Abstract

Phytic acid stores 60–90% of the inorganic phosphorus in legumes, oil seeds, and cereals, making it inaccessible for metabolic processes in living systems. In addition, given its negative charge, phytic acid complexes with divalent cations, starch, and proteins. Inorganic phosphorous can be released from phytic acid upon the action of phytases. Phytases are phosphatases produced by animals, plants, and microorganisms, notably Aspergillus niger, and are employed as animal feed additive, in chemical industry and for ethanol production. Given the industrial relevance of phytases produced by filamentous fungi, this work discusses the functional characterization of fungal phytase-coding genes/proteins, highlighting the physicochemical parameters that govern the enzymatic activity, the development of phytase super-producing strains, and key features for industrial applications.

Keywords: Phytases, Filamentous fungi, Aspergillus Niger, phyA

Introduction: an overview on phytases

Phytic acid, an inositol ring connected to six phosphate groups, is a natural constituent of plant-based foods. Nearly 60–90% of the inorganic phosphorus (Pi) in legumes, oilseeds, and cereals are stored as phytic acid [1], making Pi inaccessible for a range of metabolic processes essential for all living organisms such as energy metabolism/regulation and biosynthesis of nucleic acids/cell membranes [2, 3].

The protonation of the phosphate groups under acidic conditions generates the free form of phytic acid. At neutral pHs, the affinity of phytic acid for divalent and trivalent cations increases, especially for Mg+2, Ca+2, Cu2+, Zn2+, and Fe2+/3+, giving rise to a low-solubility chelate known as phytate [4]. Through this chelating activity, phytic acid could form complexes with starch, proteins, and lipids [5].

Phytases (myo-inositol hexakisphosphate phosphohydrolases) are phosphatases which hydrolyze phytic acid preferentially into inositol and six Pi, but the release of mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, or pentaphosphate intermediates is possible when a partial hydrolysis occurs. Phytases are classified according to the order of release of the phosphate groups from phytic acid in 3-phytases (E.C. 3.1.3.8), 4/6-phytases (E.C. 3.1.3.26), or 5-phytases (E.C. 3.1.3.72) [1, 6].

Phytases are ubiquitously produced by animals, plants, and microorganisms and usually exhibit optimal activity at pH and temperature of 4.5–6.0 and 45–60 °C, respectively, acidic pI, molecular weight around 40–70 kDa, and a monomeric state [7, 8].

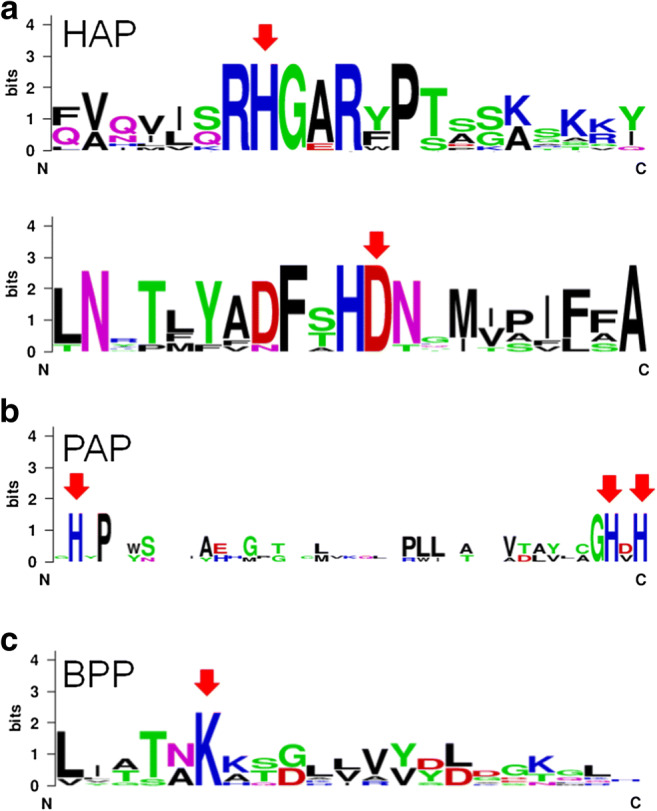

Mullaney and Ullah [9] classified phytases into histidine acid (HAPs), purple acid (PAPs), and β-propeller (BPPs, alkaline phytases) phosphatases according to their catalytic domains. Afterward, Chu et al. [10] reported the isolation and characterization of a cysteine phytase (CPhy) from a bacterium found in bovine rumen. The dependence of all living organisms on Pi has lead nature to evolve many types of catalytic mechanism to cleave phytic acid into Pi [11]. For example, recently, phytase activity was recorded in two bacterial metallo-β-lactamases family enzymes, expanding the phosphatase activity to other protein’s fold [12].

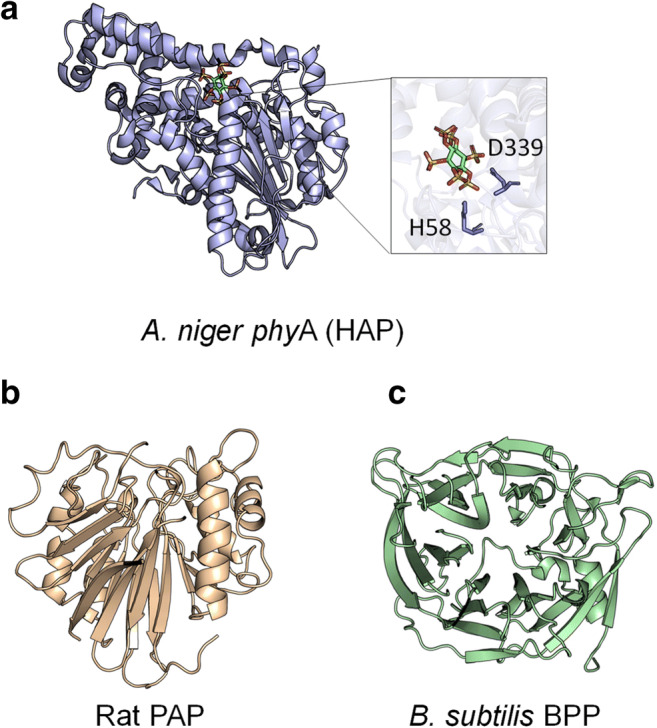

HAPs are the main focus of this work. They are recognized as “fungal phytases.” However, they are also present in bacteria, yeasts, and plants [13]. HAPs show a large α/β domain and a α domain harboring the conserved motives RHGXRXP and the catalytically active dipeptide HD (Figs. 1a and 2a). The histidine residue (H) of the former generates a phosphohistidine intermediate while the aspartic acid residue (D) of the latter donates protons to oxygen of the phosphomonoester bond, thus releasing phosphate from phytic acid [14].

Fig. 1.

Conserved sequences in HAPs (a): AAA02934.1, A niger phyB; AAL55406.1, P. oxalicum; XP_002561094.1, P. chrysogenum; XP_751964.2, A. fumigatus Af293; CAA78904.1, A niger phyA; ADK38546.1, Aspergillus sp. A25; CAC48195.1, P. lycii; CAC48160.1, A. pediades; CAC48234.1, T. pubescens; CAC48163.1, Ceriporia sp.; PAPs (b): 1UTE_A, pig phosphatase; P13686.3, acid phosphatase type 5; 1QFC_A, rat PAP; ADM32502.1, Glycine max PAP; NP_001149655.1, Zea mays; and BPPs (c): EIL89790.1, Rhodanobacter fulvus Jip2; WP_057496850.1, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia; WP_013534878.1, Pseudoxanthomonas suwonensis; ANV78615.1, Pseudomonas fluorescens; AFQ59979.1, Bacillus licheniformis; AOP13449.1, Bacillus subtilis; OBR26768.1, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens

Fig. 2.

Typical α/β-domain and smaller α-domain in HAPs (PDB code: 3K4Q, A. niger ), highlighting the residues H and D, essential for catalysis. In green, myoinositol hexakis sulfate (a); β-sheets surrounded by α-helices in PAPs (1QFC, R. novergicus) (b); and β-propeller in BBPs (3AMS, B. subtilis) (c)

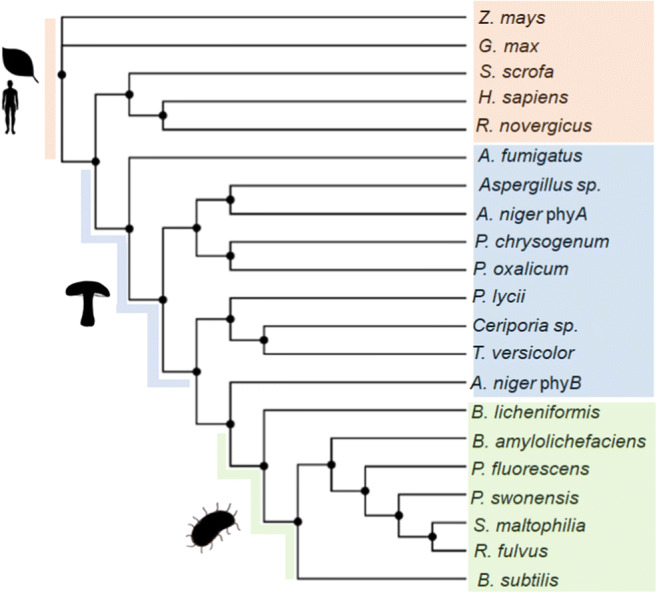

Phylogenetic studies have grouped the microbial HAPs into three clusters: 1, filamentous fungi phytases with 441–539 amino acids and pI (isoelectric point) 4.9–8.5; 2, yeast phytases with 457–479 amino acids and pI 4.4–5.8; and 3, bacterial phytases with 428–523 amino acids and pI 5.5–6.5 [15]. The phylogenetic tree obtained in the present work considered phosphatases, and they were split into HAPs, PAPs, and BPPs (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of HAPs (pale blue), PAPs (pale orange), and BBPs (pale green). Sequences: AAA02934.1, A niger phyB; AAL55406.1, P. oxalicum; XP_002561094.1, P. chrysogenum; XP_751964.2, A. fumigatus Af293; CAA78904.1, A niger phyA; ADK38546.1, Aspergillus sp. A25; CAC48195.1, P. lycii; CAC48160.1, T. pubescens; CAC48163.1, Ceriporia sp.; 1UTE_A, pig phosphatase; P13686.3, acid phosphatase type 5; 1QFC_A, rat PAP; ADM32502.1, G. max PAP; NP_001149655.1, Z. mays; EIL89790.1, R. fulvus Jip2; WP_057496850.1, S. maltophilia; WP_013534878.1, P. suwonensis; ANV78615.1, P. fluorescens; AFQ59979.1, B. licheniformis; AOP13449.1, B. subtilis; OBR26768.1, B. amyloliquefaciens

PAPs and BPPs are typically found in plants (but also in fungi and mammals) and bacteria, respectively [13]. PAPs are metalloenzymes with two β-sheets surrounded by α-helices. Conserved amino acids (H) are involved in metal coordination [16] (Figs. 1b and 2b). A few PAPs display phytase activity [17].

BPPs are typically found in Bacillus sp. [18, 19]. BPPs presents a β-propeller fold and a conserved lysine (K) in the active site, which binds to phosphate (Figs. 1c and 2c) [20]. There are some records of BPPs derived from filamentous fungi at UniProt database; however, this classification is based only on sequence homology, not in experimental data.

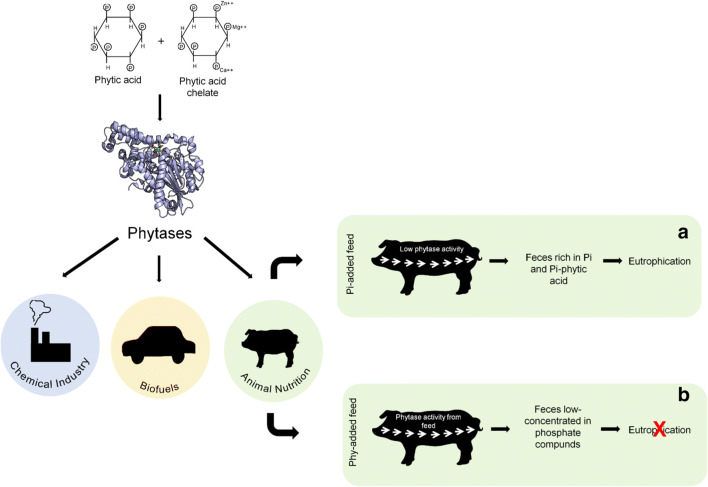

Industrial application of phytases

Phytases are employed in chemical industry to obtain myo-inositol, a six-carbon cyclic polyalcohol, and its phosphate intermediates which play a key role in cell-signaling pathways [21]. Furthermore, phytases have been applied with α-amylase for corn liquefaction aiming the first-generation ethanol production. In this regard, phytase acts releasing calcium ions from corn phytate, making them available as cofactors for the saccharifying enzymes [22, 23]. Chen et al. [24] showed that the expression of a phytase on the cell surface of S. cerevisiae increased the fermentation of sugars to ethanol around 18% compared to a control strain.

In vivo and In vitro studies expanded the spectrum of phytases application to biodegradation of organophosphorus pesticides such as monocrotophos, methyl parathion, and chlorpyrifos. By spraying an A. niger NCIM 563 phytase in Capsicum annum L pre-treated with chlorpyrifos led to a degradation of 72% of the pesticide at pH 7.0 and 35 °C [25].

Most researches have focused on the application of phytases in animal nutrition (Fig. 4). Phytases represent 60% of the animal feed enzyme market, what is correlated to 350 million dollars per year. Moreover, near 70% of feed contains phytase as additive [26, 27].

Fig. 4.

Application of phytases in industrial sectors, highlighting animal feeding

Phytases are mostly employed in feed industry

There is a consensus that monogastric animals present little or no phytase activity throughout their gastrointestinal tracts [28]. Maize, sorghum, and wheat (all rich in phytic acid) are the basis of poultry/pig diets. Then, the growth of these animals can be seriously compromised because of the unavailability of Pi and also cations and organic molecules given the chelating activity of phytic acid [29]. Therefore, pig/poultry diets must be supplemented with Pi to reach the nutritional requirements. However, feed supplementation with Pi must be undertaken with care because it counts for approximately 50–75% costs of the mineral mix and the phosphate excess, excreted to the environment through the feces, can trigger the eutrophication process in freshwater bodies [30]. Then, animal feed supplementation with phytases emerges as a promising alternative.

For application in the feed industry, phytases must exhibit high specific activity at stomach pH, substrate specificity, resistance to proteolysis by digestive proteinases, and stability during storage, pelleting, and passage through the gastrointestinal tract. Furthermore, thermostability is another important requirement because the feed-pelleting process occurs at temperatures around 65–90 °C during 30–60 s [31, 32]. However, the treatment of animal feed with phytases after the pelleting process or the vaporization of liquid phytase in the pellets are possible alternatives to avoid heat-induced enzyme inactivation [33].

Beyond poultry/pigs, microbial phytases have been also employed for fish nutrition to enhance growth, micro/macro-mineral uptake, and to reduce pollution in aquatic environments [34]. Another alternative is the use of heterologous expressing microorganisms as probiotics improving the immune system of fishes [35].

Phytases are derived mainly from genetically modified strains because the wild-type ones produce little protein relative to the commercial demand [36]. The product Natuphos has the largest market share. Natuphos contains a phytase derived from A. niger var. ficuum, produced by A. niger, described as a 3-phytase and used mainly in pig nutrition field. Natuphos has a specific activity of 100 U mg protein−1 and an optimal pH and temperature around 2.5–5.0 and 50 °C, respectively [31]. In 2016, BASF launched the new version of Natuphos, called Natuphos E, which shows an increased resistance to pepsin, adverse pH conditions, activity under high processing temperatures, and high shelf life [37].

Another phytases with outstanding features are Axtra Phy and Ronozyme, produced by DuPont and DSM/Novozymes, respectively. Axtra Phy is sourced from Buttiauxella sp. and expressed by Trichoderma reesei. Compared to Escherichia coli and Citrobacter sp. phytases, Axtra Phy shows higher relative activity at pH 5.0, heat stability up to 95 °C, and enhanced resistance to pepsin [38]. Ronozyme Hiphos and Ronozyme NP are derived from Citrobacter braakii and Peniophora lycii, respectively. Both are expressed in Aspergillus oryzae [39].

An elegant work carried out by [40] compared seven sources of phytases available on market. Overall, the amount of Pi released is proportional to the concentration of enzyme used when the conditions of crop, stomach, and intestine were simulated. Comparing the two phytases from fungi, Ronozyme NP and Natuphos, the former showed higher Kcat for phytate at pH 3.0 and 5.0 at 37 °C, but also showed to be more susceptible to the action of proteases than Natuphos.

Danisco [41] said that the feed supplementation with phytase could result in cost savings of $1.08 and $1.23 per feed tonne for pig and poultry, respectively, given the release of 20% more phosphorous and calcium. Generally, the supplementation of animal feed with 250–500 FTU (phytase units)/kg is recommended, but the benefits can be amplified using higher doses of phytases, such as more than 500 FTU. For example, BASF showed an increase of 50% in fortification of pigs employing 1000 FTU/kg feed. For poultry, this increase was around 30% [37].

Several factors affect the animal response upon the application of phytase in feed such as its concentration, type, source, solubility, the dietary calcium concentration, and the presence of additional exogenous potentiating enzymes [42, 43].

Several works have highlighted the effect of a calcium-rich diet on phytase activity. Calcium, mainly found in limestone, interacts with phytate molecule, making the substrate less accessible to phytases [44, 45]. Alternatives to overcome this problem are a profitable field of study for the next years given that the separation of limestone and feed is an arduous task.

Given the relevance of phytases derived from fungal strains in industrial settings, this work discusses the functional characterization of filamentous fungi phytase-coding genes and proteins giving emphasis to the evolution of knowledge regarding this catalyst.

Phytases from filamentous fungi (HAPs)

Phytase-coding genes and proteins of some filamentous fungi have been characterized (Table 1). The initial researches were carried out with A. niger strains, and it can be considered as a model species regarding phytase production.

Table 1.

Characterization of phytase-coding genes and enzymes derived from filamentous fungi

| Source | Host strain (phytase activity) | ORF (bp) | I (bp) | Ptn (aa) | SP (aa) | pI | MW (kDa) | pH | T (°C) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. niger NRRL 3135 | A. niger (7.6 U mL−1) | 1401 | 102 | 467 | 18/19 | ND | 48.8 | 2.5/5.0 | 55 | van Hartingsveld et al., 1993. |

| A .niger var. ficuum | x (ND) | 1437 | 54/59 | 479 | ~20 | ND | ~52 | ND | ND | Ehrlich et al., 1993. |

| A. terreus 9A-1 | A. niger NW205 (22 U mL−1) | 1338 | 48 | 446 | ND | 5.0 | 61 | 5.5 | 49 | Mitchell et al., 1997. |

| M. thermophila | A. niger NW205 (8.5 U mL−1) | 1461 | 57 | 487 | ND | 4.9 | 63 | 5.5 | 55 | Mitchell et al., 1997. |

| E. nidulans | A. niger NW205 (ND) | 1389 | 54 | 463 | ND | ND | 51 | ND | ND | Pasamontes et al., 1997. |

| T. thermophilus | A. niger NW205 (ND) | 1398 | ND | 466 | ND | 5.2 | 128 | ND | ND | Pasamontes et al., 1997. |

| A. fumigatus | A. niger NW205 (ND) | 1317 | 56 | 439 | 26 | 7.3 | 60 | 4.0/6.0–6.5 | ND | Pasamontes et al., 1997. |

| T. lanuginosus | F. venenatum (110 U mg−1) | 1356 | 56 | 452 | 22 | 5.4 | 51 | 6.0 | ~65 | Berka et al., 1998. |

| A. niger | S. cerevisiae INVSc1 (27.59 U mL−1) | 1400 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 120 | 2.0–2.5/5.0–5.5 | 55–60 | Han et al., 1999. |

| P. lycii | A. oryzae (1080 U mg−1)* | 1317 | ND | 439 | ND | 4.3 | 72 | 4.0–4.5 | 50–55 | Lassen et al., 2001. |

| A. pediades | A. oryzae (400 U mg−1)* | 1359 | ND | 453 | ND | 5.0 | 59 | 5.0–6.0 | 50 | Lassen et al., 2001. |

| Ceriporia sp. | A. oryzae (700 U mg−1)* | 1326 (PhyA1) | ND | 442 | ND | 6.4 | 59 | 5.5–6.0 | 55–60 | Lassen et al., 2001. |

| Ceriporia sp. | A. oryzae (1040 U mg−1)* | 1326 (PhyA2) | ND | 442 | ND | 4.6 | 54 | 5.0–6.0 | 40–45 | Lassen et al., 2001. |

| T. pubescens | A. oryzae (1210 U mg−1)* | 1329 | ND | 443 | ND | 4.4 | 62 | 5.0–5.5 | 50 | Lassen et al., 2001. |

| niger 113 | P. pastoris (39 U mL−1) | 1344 | ND | 448 | 19 | 4.6 | 64 | 2.0/5.0 | 60 | Xiong et al., 2004. |

| A. niger SK-57 | P. pastoris GS115 (865 U mL−1) | 1347 | ND | 449 | ND | ND | 120 | 2.5/5.5 | 60 | Xiong et al., 2005. |

| A. oryzae SH18 | A. oryzae RIB40 niaD− (2 U mL−1) | 1341 | 68 | 447 | 19 | ND | 70 | 5.5–6.0 | 50 | Uchida et al., 2006. |

| P. oxalicum PJ3 | P. pastoris GS115 (12 U mL−1) | 1329 | ND | 443 | ND | ND | 62.5 | 4.5 | 55 | Lee et al., 2007 |

| A. fumigatus WY-2 | P. pastoris GS115 (16 U mL−1) | 1395 | 61 | 465 | ND | 5.9 | 88 | 5.5 | 55 | Wang et al., 2007. |

| A. niger N-J | P. pastoris GS115 (503 U mg−1) | 1344 | ND | 448 | ND | ND | 66–80 | 2.5–5.5 | 55 | Zhao et al., 2007. |

| A. japonicus | P. pastoris (100 U mL−1) | 1404 | ND | 468 | 21 | 4.9 | 66 | 5.5 | 50 | Promdonkoy et al., 2009. |

| A. niger | P. pastoris | 1404 | ND | 468 | 21 | 4.9 | 66 | 5.5 | 50 | Promdonkoy et al., 2009. |

| A. ficuum NTG-23 | (2.1 U mg−1) | 1380 | ND | 460 | ND | ND | 65.5 | 1.3 | 67 | Zhang et al., 2010. |

| E. parvum | P. pastoris KM71 (2.7 U mL−1) | 1380 | 84 | 460 | ND | ND | ~70 | 5.5 | 50 | Fughtong et al., 2010. |

| A. aculeatus RCEF 4894 | P. pastoris GS115 (52,700 U mg−1) | 1404 | ND | 467 | 19 | 6.7 | ~74.8 | 5.5 | ND | Ma et al., 2011. |

| N. spinosa BCC41923 | P. pastoris KM71 (113.05 U mL−1) | 1317 | 57 | 439 | ND | ND | 52 | 5.5 | 50 | Pandee et al., 2011. |

| A. niger NII08121 | E. coli BL21 DE(3) (8 U mL−1) | 1506 | x | 502 | ND | 4.9 | 49 | 6.5 | 50 | Ushasree et al., 2014. |

| A. niger NII08121 | K. lactis (198 U mL−1) | 1506 | x | 502 | ND | ND | 50 | 5.5 | 55 | Ushasree et al., 2014. |

| P. chrysogenum CCT1273 | P. griseoroseum (2.86 U μg −1) | 1452 | x | 483 | 18 | 7.6 | 51 | 2.0–5.0 | 50 | Corrêa et al., 2015. |

| A. oryzaeSBS50 | x (60 U mg−1) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ~80 | 5.0 | 50 | Sapna, 2017. |

| S. thermophile | P. pastoris (1190 U mg−1)* | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 75 | 5.0 | 60 | Maurya et al., 2017. |

| M. importuna | P. pastoris (ND) | 1638 | ND | 546 | x | ND | 60 | 6.5 | 25 | Tan et al., 2017. |

| A. aculeatus APF1 | x (13.82 U mg−1)* | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 25–35 | 3.0 | 50 | Saxena et al., 2019. |

| A. foetidus MTCC11682 | x (294.5 U mg−1) | 1176 | ND | 391 | ND | ND | 90.5 | 3.5/5.5 | 37 | Ajith et al., 2019. |

ORF open reading frame, bp base pairs, phytase activity enzyme activity in culture supernatant or purified* enzyme preparation, I intron, Ptn protein, aa amino acids, SP signal peptide, pI estimated isoelectric point, MW molecular weight assessed by SDS-PAGE, T temperature, ND not determined

The first relate of a phytase (PHYA) produced by A. niger NRRL 3135 was done by Irwing and Cosgrove [46]. A. niger grown in corn starch produced the phytases PHYA and PHYB, which exhibits the highest activities at pH 2.5/5.0 and 2.5 at 58 °C, respectively.

Based on the researches developed by Ullah and Gibson [47] and Ullah [48], the phyA gene was isolated and characterized from a genomic library. phyA shows a CAAT and TATA-box-like structures in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) and a putative signal peptide of 18–19 amino acids. The gene presents a 102-base pair intron and encodes a 467-amino acid protein with a molecular weight of 80 kDa assessed by SDS-PAGE (50 kDa after deglycosylation) and 10 putative glycosylation sites. phyA was cloned into the plasmid pAF2-2S used to transform A. niger cells grown under derepression conditions, i.e., at low phosphate concentration. The enzyme activity increased up to 12-fold in the transformant strains. Subsequently, Southern blotting analysis showed that the copy number of phyA ranged from two to 15 in the recombinant strains [49].

The phyB gene was firstly isolated from a genomic library of A. niger (ficuum). PHYB presents 479 amino acids, 20-amino acid leader sequence, molecular weight of 52 kDa, and eight potential glycosylation sites. PHYB exhibits 23.5% amino acid identity with PHYA and 46% neutral substitutions [50].

The optimal pH for PHYA and PHYB activities are 2.5/5.0 and 2.5, respectively. This divergence is based on the charge distribution of the amino acids in the active site. While PHYB has two negatively charged amino acids, PHYA has also Lys 91, Lys 94, Lys 300, and Lys 301, which remain positively charged at pH 5.0, increasing the affinity of PHYA for the negatively charged phytic acid molecule [51].

Zhang and collaborators [52] isolated and characterized a PHYB from A. ficuum with an optimal pH and temperature of 1.3 and 67 °C, respectively. This is the lowest optimal pH reported to date for an active phytase.

A phy gene that shares the same features of phyB was isolated from A. niger var. awamori, cloned into pFF1 plasmid and used to transform A. niger var. awamori ALK02268. Up to 7-fold increase in phytase activity and gene copy numbers was found in the transformants [53].

The PHYA proteins isolated from Myceliophthora thermophila and Aspergillus terreus 9A-1 display 48 and 60% identity, respectively, with the PHYA from A. niger. Both enzymes show higher activity when phytic acid is used as substrate at pH 5.5 or 6.0, helping to characterize those enzymes as phytases [54].

The molecular mechanisms underlying the expression of phytase-coding genes are not well understood in filamentous fungi as in bacteria and yeasts. Phytase production in filamentous fungi is associated with growth and is induced under low Pi concentrations, as first shown by Shieh and Ware [55] while assessing the effect of Pi concentration on growth and phytase production by A. niger NRRL 3135. They observed that the addition of more than 0.06 g/L of Pi noticeably increase the microorganism growth, but decrease the phytase activity. These data corroborate with those found by van Hartingsveldt and collaborators [49], who observed by Northern blotting an approximately 1.8-kb band related to phyA RNA when A. niger NRRL 3135 was grown in low Pi condition, but not under high Pi concentration. In addition, the phytase gene NCU06351 in Neurospora crassa is downregulated when this fungi is grown under high Pi concentrations [56].

A study carried out by [57] pointed out that production of phytases by A. niger under submerged or solid conditions relies on fungal morphology (dispersed versus pelleted mycelium) and media composition (mainly low concentration of Pi, as highlighted above). Given that phytic acid is not required for phytase production by filamentous fungi [49], a plethora of substrates have been employed, such as glucose, fructose, galactose, maltose, sucrose, starch, rye flour, corn/soybean meal, wheat bran, and sugarcane bagasse [58, 59], highlighting the constitutive expression of this catalyst in fungi.

The strong dependence of phytase production by Pi concentration in culture medium can be solved by the employment of strong and constitutive promoters to control the expression of recombinant phytase genes. A recombinant lineage of Penicillium griseoroseum T73 expressing a Penicillium chrysogenum CCT1273 phytase with a 5.1-fold increase in phytase activity compared with the nontransformed host strain was obtained by our research group by means of using the strong and constitutive promoter gpdA from Aspergillus nidulans [60]. In a similar way, Uchida et al. [61] reported the isolation and cloning of an A. oryzae RIB40 phytase-coding gene downstream the strong promoter P-No8142, which contains cis elements involved in the regulation of α-amylase expression in A. oryzae. As a result, one A. oryzae RIB40 nia− transformant strain reached an approximately 20-fold increase in enzyme activity compared with the native host strain.

As highlighted above, the vast majority of phytase-coding genes described in the literature are from Ascomycete fungi, mainly Aspergillus sp. The first report of phytases produced by basidiomycetes was made by Lassen at al. [62]. Genes encoding 6-phytases were isolated from P. lycii CBS 686.96, Agrocybe pediades CBS 900.96, Trametes pubescens CBS 100232, and Ceriporia sp. CBS 100231. The corresponding cDNAs were obtained and the proteins were expressed in A. oryzae. The recombinant strains exhibited up to 12-fold greater phytase activity compared with PHYA from A. niger. The ORFs of these genes encode proteins with 439–453 amino acids, a 19-amino acid signal peptide (except for P. lycii CBS 686.96, whose signal peptide has 29 amino acids), 6–10 glycosylation sites, and a pI of 4.35–6.40. The optimal pH and temperature were 4.0–6.0 and 55–60 °C, respectively.

A phytase from the mushroom Lentinus edodes was characterized by Zhang et al. [63] and presents a molecular mass of 14 kDa and optimal pH and temperature of 5.0 and 37 °C, respectively. Low molecular mass seems to be a particular feature of phytases derived from basidiomycete fungi given that those obtained from Volvariella volvaceae and Flammulina vellutipes shows 14 and 14.8 kDa, respectively [64, 65].

The first relate of a psychrophilic phytase was done for the filamentous fungi Morchella importuna. The best activity was found at pH 6.5 and 25 °C, what makes this enzyme a promising candidate as feed additive for fishes [66].

A recent study pointed out new fungi sources of phytases, for example, Acrophialophora sp., Humicola sp., Lichtheimia sp., and Scytalidium sp. Among them, Acrophialophora levis showed a specific activity of 81.72 U/mg protein. However, the best strain evaluated in this study was Aspergillus tubingensis (331.32 U/mg protein) [67].

Filamentous fungi phytases are expressed by yeast, plant, and animal cells

In addition to the filamentous fungi highlighted above, yeast strains like Pichia pastoris have been widely employed as host to increase phytase production under methanol-induced conditions by cloning the gene of interest driven by the AOX (alcohol oxidase) promoter in the pPICZαA plasmid or others [68, 69]. P. pastoris is an attractive host for protein expression due to its GRAS (Generally Regarded as Safe) status, the well-known strategies for protein expression, ability to perform post-translational modifications and production of low background proteins. Alternatively, Kluyveromyces lactis strains have also been adopted as host for phytase production [70]. Another emergent yeast for heterologous expression of fungi phytases is Ogataea thermomethanolica [71].

The production of A. niger SK-57 phytase by P. pastoris was evaluated by Xiong et al. [72]. Vectors containing both native A. niger SK-57 phyA and the α-factor signal sequence of the wild-type Saccharomyces cerevisiae or modified sequences according to the codon usage of P. pastoris have been designed. A 14-fold increase in phytase activity was found in transformants wherein both the native signal sequence and the ORF were codon optimized.

Zhao et al. [73] reported the obtaining of a P. pastoris strain with a 30,000-fold increase in phytase activity compared with A. niger N-J wild-type strain. Initially, phytase-producing microorganisms were screened in solid culture media containing calcium phytate and A. niger N-J showed promising phytase production levels. The phytase-coding gene (1344 base pairs [pb]) encodes a 448-amino acid protein with a calculated molecular weight of 49.2 kDa. SDS-PAGE showed a diffused band between 66 and 80 kDa, which may result from the protein’s 11 potential glycosylation sites.

Prondomkoy et al. [74] assessed the phytase production of 300 fungal isolates, and Aspergillus japonicus BCC 18313 (TR86) and A. niger BCC 18081 (TR70) showed the best results. The activity of the enzymes expressed by P. pastoris was approximately 1000-fold higher than that observed in the crude extract of Aspergillus. Both genes present 1404 bp and 95% identity with A. niger CBS 513.88 phytase and encode a 468-amino acid protein with a molecular weight of 51 kDa and pI 4.9. These genes exhibit the typical conserved domains of histidine acid phosphatases, a 21-amino acid signal peptide, eight potential N-glycosylation sites, and molecular weight of 66 kDa according to SDS-PAGE.

Pandee et al. [32] isolated and characterized the PhyN phytase from Neosartorya spinosa BCC 41923. This protein has 439 amino acids and share 91–96% identity with phytases produced by A. fumigatus strains. The optimal pH and temperature are 5.5 and 50 °C, respectively.

Filamentous fungi and yeast strains are the preferred hosts for production of heterologous phytases. Bacterial strains showed to be the last option to express filamentous fungi phytases probably because of the presence of rare codons, the formation of inclusion bodies, and the absence of post-translational modifications [75].

When Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLysS was employed to express the PHYA from A. niger SRRC256, a strong band around 56 kDa was observed in the electrophoretic profile of the insoluble fraction of the cells and the loss in activity (80-fold lower than that observed for A. niger wild-type strain) might be a result from steps during the protein refolding. The inclusion bodies resulting from the high expression of genes cloned into E. coli is a common phenomenon [76].

An efficient production of heterologous proteins by bacterial strains can be achieved by the overexpression of chaperones and other folding-related proteins [77], what was showed when the A. niger NII08121 phytase was co-expressed with the chaperones GroES/EL employing E. coli BL21 (DE3) as the host strain. The chaperones aid the protein folding and an increase of 16-fold in phytase activity was observed. Moreover, the shift in optimum pH of the recombinant phytase (pH 6.5 instead of 2.5/5.0) is probably due to the inability of the E. coli cells to perform glycosylation (post-translational modification essential to modulate the protein half-life or enzymatic activity) [70]. By the way, several efforts have been done to elucidate the glycosylation process in bacteria [78].

Phytases derived from filamentous fungi have been also produced in nonmicrobial hosts, including microalgae and plants. The introduction of phytases in microalgae is an interesting strategy given its high nutritional value, reducing the costs with addition of amino acids in feed, for example [79].

The introduction of phytases in plants aim to increase the soil phosphorus bioavailability for these crops and to maintain the activity of phytase in seeds, thus avoiding future animal feed supplementation with Pi [80].

Several researches have shown the reduction in phytic acid content of seeds following the expression of fungal phytases by plants, for example, wheat (reduction around 12–76%) [81] and Brassica napus (mutants showed an accumulation of 20.6–46.9% more phosphorous compared with the wild type when phytic acid was employed as phosphate source) [82]. Geeta et al. [83] showed that seeds of Zea mays expressing an A. niger phytase had 0.6- to 5-fold more inorganic phosphorous content than the non-expressing ones.

The use of plants for production of microbial phytases was extensively discussed by Gontia et al. [84]. Several parameters should be taken into consideration to evaluate the effect of phytase in plants, for example, the nutritional and metabolic features associated with phosphorous acquisition in wild-type and transgenic plants and the physicochemical conditions of soil to match the requirements of the enzyme [85].

In addition to plants, animals such as the fish Oryzias latipes was employed for production of A. niger phytase to reduce excretion of phosphate compounds by feces into the environment [86]. The authors also reported the obtaining of a transgenic tilapia with an approximately 43.5% reduction in phytate excretion in the feces compared to the wild-type one.

Another example is the “Enviropig,” a Cassie line of pigs expressing phytases in saliva. The phosphorous retention in these animals reached 34% more than that observed for the phytase non-expressing animals. However, the phytase secreted by the Enviropig is sourced from E. coli [87]. Furthermore, a recent research showed that the introduction of phytases, β-glucanases, and xylanases in salivary glands of pigs reduced (23.2–45.8%) the nitrogen and phosphorous content on feces [88].

Thermostability: an issue for industrial application

The main bottlenecks to the application of phytases as animal feed supplement are resistance to proteases found in the gastrointestinal tract, activity at 37–40 °C [89], typical temperature in the stomach of monogastric animals, and thermostability. Phytases must be thermostable to be employed as an animal feed additive given the high temperatures employed in the pelleting process [32, 33]. However, the improvement and balance of optimum temperature, thermal stability, and catalytic efficiency is an arduous task.

Several works have been carried out in order to investigate the structural/molecular determinants of the thermal stability of phytases, but there is no consensus up to date [90]. Sometimes, the accumulation of mutations in a phenotype that previously showed a slight improvement in a specific feature is desirable and reflects exactly what happens in a natural environment [91].

The phytase isolated from the mushroom L. edodes presents optimal activity at 37 °C and residual activity of 84, 62, and 50% after incubation at 60, 70, and 80 °C during 40 min [92], being an excellent alternative for application in animal feed industry. Some works dealing with thermostability of phytases from filamentous fungi are highlighted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Thermostability of phytases from filamentous fungi

| Source | Host strain | Thermostability (residual activity (%)) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. niger | x | 40%/68 °C/10 min | Ullah e Gibson, 1987 |

| A. fumigatus ATCC 34625 | A. niger | 90%/100 °C/20 min 20%/100 °C/120 min | Pasamontes et al., 1997 |

| T. lanuginosus CBS 586.94 | F. venenatum | ~42%/65 °C/20 min | Berka et al., 1998 |

| A. niger | S. cerevisiae INVSc1 | 62.6% (glycosylated) e 37.3% (deglycosylated)/80 °C/15 min | Han et al., 1999 |

| P. lycii CBS 686.96 | A. oryzae A1560 | 62%/80 °C/60 min | Lassen et al., 2001 |

| A. niger 113 | P. pastoris | 25%/80 °C/10 min | Xiong et al., 2004 |

| A. niger SK-57 | P. pastoris | 50%/80 °C/10 min | Xiong et al., 2005 |

| A. niger N-J | P. pastoris | 75,2%/80 °C/15 min 74,1%/85 °C/15 min 68.8%/90 °C/15 min | Zhao et al., 2007 |

| A. niger N-3 | P. pastoris | 45%/90 °C/5 min | Shi et al., 2009 |

| A. japonicus BCC 18313 | P. pastoris | 50%/90 °C/5 min | Prondomkoy et al., 2009 |

| A. niger BCC 18081 | P. pastoris | 60%/100 °C/5 min | Prondomkoy et al., 2009 |

| E. parvum BCC 17694 | P. pastoris | 60%/100 °C/40 min | Fugthong et al., 2010 |

| A. aculeatus RCEF 4894 | P. pastoris | 86.1%/90 °C/10 min 74.6%/90 °C/30 min | Ma et al., 2011 |

| N. spinosa BCC 41923 | P. pastoris | ~60%/90 °C/20 min | Pandee et al., 2011 |

| A. japonicus | P. pastoris | 50%/50 oC/40 min | Fonseca-Maldonado, 2014 |

| T. lanuginosus | x | 50%/70 oC/140 min 50%/80 oC/45 min 50%/90 oC/25 min | Makolomakwa et al., 2017 |

| A. oryzae | x | 10%/80 oC/30 min | Sapna, 2017 |

Microorganisms that inhabit high-temperature environments are valuable sources of thermostable enzymes. The thermophilic fungus Thermomyces lanuginosus CBS 586.94 produces a phytase 47.5% identical to that of A. niger M94550. Its optimal temperature is 65 °C, and it is approximately eight times more thermostable than that of A. niger after incubation at 65 °C for 20 min [93]. Another phytase from T. lanuginosus shows the best activity at 55 °C, but no activity was recorded after incubation at 90 °C during 10 min.

A. niger NRRL 3135 phyA retains only 40% of its initial activity after incubation for 10 min at 68 °C [47]. PHYA has a molecular mass of 120 kDa when expressed by S. cerevisiae INVSc1. The glycosylated and deglycosylated (50 kDa) enzymes showed a residual activity of 62.6 and 37.3%, respectively, after treatment at 80 °C for 15 min [94]. These data show the importance of glycosylation to protect phytases from heat denaturation. For this reason, yeast strains are the organisms of choice to express phytases given their tendency to hyperglycosylated proteins at consensus sites [95].

Phytase from A. aculeatus RCEF 4894 shows desirable features to be employed in animal feed industry. After its treatment at 90 °C for 10 and 30 min, 86.1 and 74.6% of the initial activity were maintained, respectively. The authors attribute this high thermostability to the 23 potential glycosylation sites (asparagine residues) observed in the protein sequence [96] given that N-glycosylation is an important strategy to improve the production/catalytic properties of some proteins [97].

Two of the most thermostable phytases found in literature are those derived from A. fumigatus ATCC 34625 and P. lycii CBS 686.96. The first one maintains approximately 90 and 20% of its initial activity following incubation at 100 °C for 20 and 120 min, respectively, and the latter showed the highest thermostability, with approximately 62% of its initial activity remaining following incubation at 80 °C for 60 min. A study carried out by Nielsen et al. [98] showed that the P. lycii phytase was found to be the most thermostable phytase characterized.

In the last two decades, protein engineering has emerged as a key tool to develot biocatalysts with features which overcome the drawbacks of the wild-type ones, thus promoting and expanding their industrial applications [99, 100]. Several strategies could be employed to alter the response protein-temperature. Some examples are related to the addition of new hydrogen bonds, disulfide bridges, beta-turns or flexi termini stabilization, enhancement of hydrophobic packing, and alpha helix/beta-sheet stabilization [101].

Some regions of PHYA from A. niger (the salt bridges between Glu125-Arg163, Asp299-Arg136, Asp266-Arg219, Asp339-Lys278, Asp335-Arg136, and Asp424-Arg428) were predicted as thermolabile by bioinformatic tools given their expansion upon the increase of temperature. This data could be the basis to engineer novel thermostable phytases with desirable properties [102].

Another work showed that the replacement of the residues I144 and T252 in PHYA (single or double mutant) to glutamic acid and arginine, respectively, improves the thermostability by a factor of 20% compared with the wild-type one due to the formation of novel hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions [103].

Han et al. [104] proposed several mutations in PHYA from A. niger based on the structure of A. fumigatus phytase (the most thermostable phytase in literature). At 80 °C for 1 h, the mutants 1 (35-ANESVISP-42, 163-RAQPGQ-168, and 248-TSTVDTK-254 in PHYA correspond to 35-EDELSVSS-42, 163-GATNRA-168, and 248-RTSDASQ-254 in A. fumigatus phytase) and 2 (S39V, S42P, T165Q, N166P, R167G, R248T, D251V, A252D, and Q254K) retained 58 and 41% of the initial activity, respectively, while the native showed a residual activity of only 21%. However, these mutations resulted in a reduced catalysis efficiency possibly due to the proximity to substrate binding motifs.

Conclusion and future remarks

In this work, the evolution of knowledge of filamentous fungi phytases field as well as the bottlenecks these enzymes face to be employed in industry was discussed. The main application of phytases is as feed supplement; however, this spectrum has been expanded to ethanol production and degradation of organophosphorus compounds. Every year, nearly 20% of the manuscripts published about phytase discusses A. niger as the source of this enzyme (sciencedirect.com data); however, basidiomycetes have emerged as promising alternatives. The investigation about other sources of phytases is especially interesting to cope the requirements for application in new industrial sectors. In addition, researches about the interaction phytase-food are a profitable field for new discoveries. The high demand for phytases opens horizons for the discovery of catalysts with improved properties to be applied in industry.

Funding information

The authors received financial support from CNPq (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development) and FAPEMIG (Foundation for Research Support of the State of Minas Gerais).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rao DECS, Rao KV, Reddy TP, Reddy VD. Molecular characterization, physicochemical properties, known and potential applications of phytases: an overview. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2009;29:182–198. doi: 10.1080/07388550902919571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh B, Satyanarayana T. Microbial phytases in phosphorous acquisition and plant growth promotion. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2011;17:93–103. doi: 10.1007/s12298-011-0062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Secco D, Bouain N, Rouached A, Prom-u-thai C, Hanin M, Pandey AK. Phosphate, phytase and phytases in plants: from fundamental knowledge gained in Arabdopsis to potential biotechnological application in wheat. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2017;37:898–910. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2016.1268089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohn L, Meyer AS, Rasmussen SK. Phytate: impact on environment and human nutrition. A challenge for molecular breeding. J Zheijang Univ Sci B. 2008;9:165–191. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0710640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vohra A, Satyanarayana T. Phytases: microbial sources, production, purification, and potential biotechnological applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2003;23:29–60. doi: 10.1080/713609297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrientos L, Scott JJ, Murthy PPN. Specificity of hydrolysis of phytic acid by alkaline phytase from lily pollen. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1489–1495. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konietzny U, Greiner R. Bacterial phytase: potential application, in vivo function and regulation of its synthesis. Braz J Microbiol. 2004;35:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lei XG, Porres JM. Phytate enzymology, applications, and biotechnology. Biotechnol Lett. 2003;25:1787–1794. doi: 10.1023/a:1026224101580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mullaney EJ, Ullah AHJ. The term phytase comprises several different classes of enzymes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;312:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu H-M, Guo R-T, Lin T-W, Chou C-C, Shr H-L, Lai H-L, Tang T-Y, Cheng K-J, Selinger BL, Wang A-HJ. Structures of Selenomonas ruminantium phytase in complex with persulfated phytate: DSP phytase fold and mechanism for sequential substrate hydrolysis. Structure. 2004;12:2015–2024. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mullaney EJ. Phytases: attributes, catalytic mechanisms and applications in: turner. In: Turner BL, Mullaney EJ, editors. Inositol phosphates: linking agriculture and the environment. Wallingford: CABI; 2007. pp. 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villamizar GAC, Funkner K, Nacke H, Foerster K, Daniel R. Functional metagenomics reveals a new catalytic domain, the metallo-β-lactamase superfamily domain, associated with phytase activity. mSphere. 2019;4:e00167–e00119. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00167-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plaxton W, Lambers H. Annual plant reviews, phosphorous metabolism in plants. first. New Delhi: Wiley Blackwell; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oh B-C, Choi W-C, Park S, Kim Y-O, Oh T-K. Biochemical properties and substrate specificities of alkaline and histidine acid phytases. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;63:362–372. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1345-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar V, Singh G, Verma AK, Agrawal S. In silico characterization of histidine acid phosphatases. Enzyme Res. 2012;2012:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2012/845465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guddat LW, McAlpine AS, Hume D, Hamilton S, Jersey J, Martin JL. Crystal structure of mammalian purple acid phosphatase. Structure. 1999;7:7. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuang R, Chan KH, Yeung E, Lim BL. Molecular and biochemical characterization of AtPAP15, a purple acid phosphatase with phytase activity, in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:199–209. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.143180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schenk G, Mitic N, Hanson GR, Comba P. Purple acid phosphatase: a journey into the function and mechanism of a colorful enzyme. Coord Chem Rev. 2013;257:473–482. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar V, Yadav AN, Verma P, Sangwan P, Saxena A, Kumar K, Singh B. β-Propeller phytases: diversity, catalytic attributes, current developments and potential biotechnological applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;98:595–609. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.01.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang H, Shi P, Wang Y, Luo H, Shao N, Wang G, Yang P, Yao B. Diversity of beta-propeller phytase genes in the intestinal contents of grass carp provides insight into the release of major phosphorous from phytase in nature. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:1508–1516. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02188-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki T, Nishioka T, Ishizuka S, Hara H. A novel mechanism underlying phytate-mediated biological action-phytate hydrolysates induce intracellular calcium signaling by a Gαq protein-coupled receptor and phospholipase C-dependent mechanism in colorectal cancer cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010;54:947–955. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris P, Xu F, Kreel NE, Kang C, Fukuyama S. New enzyme insights drive advances in commercial ethanol production. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2014;19:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makolomakwa M, Puri AK, Permaul K, Singh S. Thermo-acid-stable phytase-mediated enhancement of bioethanol production using Colocasia esculenta. Bioresour Technol. 2017;235:396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.03.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X, Xiao Y, Shen W, Govender A, Zhang L, Fan Y, Wang Z. Display of phytase on the cell surface of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to degrade phytate phosphorous and improve bioethanol production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100:2449–2458. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-7170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah PC, Kumar VR, Dastager SG, Khire JM. Phytase production by Aspergillus niger NCIM 563 for a novel application to degrade organophosphorous pesticides. BMC Express. 2017;7:66. doi: 10.1186/s13568-017-0370-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhavsar K, Khire JM. Current researches and future perspectives of phytase bioprocessing. RSC Adv. 2014;4:26677–26691. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feed Management (2014) How to select the best phytases for your feed formulation? http://www.feedmanagement-digital.com/201401/Default/10/0. Accessed 30 May 2018

- 28.Humer E, Schwarz C, Schedle K. Phytase in pig and poultry nutrition. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2015;99:605–625. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen AVF, Tetens I, Meyer AS. Potential of phytase-mediated iron release from cereal-based foods: a quantitative view. Nutrients. 2013;5:3074–3098. doi: 10.3390/nu5083074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar A, Chanderman A, Makolomakwa M, Perumal K, Singh S. Microbial production of phytases for combating environmental phosphate pollution and other diverse applications. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2015;46:556–591. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wyss M, Brugger R, Kronenberger A, Rémy R, Fimbel R, Oesterhelt G, Lehmann M, van Loon APGM. Biophysical characterization of fungal fitases (myo-inositol hexakisphosphate phosphohydrolases): catalytic properties. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:367–373. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.367-373.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pandee P, Summpunn P, Wiyakrutta S, Isarangkul D, Meevootisom V. A thermostable phytase from Neosartorya spinosa BCC 41923 and its expression in Pichia pastoris. J Microbiol. 2011;49:257–264. doi: 10.1007/s12275-011-0369-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao L, Wang W, Yang C, Yang Y, Diana J, Yakupitiyage A, Luo Z, Li D. Application of microbial phytase in fish feed. Enzym Microb Technol. 2007;4:497–507. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar V, Sinha AK, Makkar HPS, De Boeck G, Becker K. Phytate and phytase in fish nutrition. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2012;96:335–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2011.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santos KO, Costa-Filho J, Riet J, Spagnol KL, Nornberg BF, Kütter MT, Tesser MB, Marins LF. Probiotic expressing heterologous phytase improves the immune system and attenuates inflammatory response in zebrafish fed with a diet rich in soybean meal. Fish Shelffish Immunol. 2019;93:652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, Ridgway D, Gu T, Moo-Young M. Bioprocessing strategies to improve heterologous protein production in filamentous fungal fermentations. Biotechnol Adv. 2005;23:115–129. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.BASF (2016) The phytase pioneer, BASF, sets a new benchmark in animal nutrition with Natuphos® E. https://www.basf.com/en/company/news-and-media/news-releases/2016/01/p-16110.html. Accessed 8 November 2017

- 38.Dupont (2016) Axtra® Phy. http://animalnutrition.dupont.com/fileadmin/user_upload/live/animal_nutrition/documents/open/DuPont-Axtra-PHY-brochure-2016.pdf. Accessed 20 November 2017

- 39.DSM (2017) https://www.dsm.com/content/dam/dsm/anh/en_US/documents/DSM/Whitepaper_Enzymes_CTA2.pdf. Accessed 18 November 2017

- 40.Menezes-Blackburn D, Gabler S, Greiner R. Performance of seven commercial phytases in an in vitro simulation of poultry digestive tract. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:6142–6149. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b01996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Danisco (2014) https://www.poultryworld.net/Nutrition/Articles/2014/5/Danisco-launches-new-products-at-AveSui-1521698W/. Accessed 20 November 2017

- 42.Cowieson AJ, Ruckebusch P, Sorbara JOB, Wilson JW, Guggenbuh P, Roos FF. A systematic view on the effect of phytase on ileal amino acid digestibility in broilers. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2017;225:182–194. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santos TT, O’Neill HVM, Gonzalez-Ortiz G, Camacho-Fernandez D, Lopez-Coello C. Xylanase, protease and superdosing phytase interactions in broiler performance, carcass yield and digesta transit time. Anim Nutr. 2017;3:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilkinson SJ, Selle PH, Bedford MR, Cowieson AJ. Separate feeding of calcium improves performance and ileal nutrient digestibility in broiler chicks. Anim Prod Sci. 2014;54:172. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abdollahia MR, Duangnumsawangb Y, Kwakkelb RP, Steenfeldtc S, Bootwallad SM, Ravindran V. Investigation of the interaction between separate calcium feeding and phytase supplementation on growth performance, calcium intake, nutrient digestibility and energy utilization in broiler starters. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2016;219:48–58. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Irwing GCJ, Cosgrove DJ. Inositol phosphate phosphatases of microbiological origin: the inositol pentaphosphate products of Aspergillus ficuum phytases. J Bacteriol. 1972;112:434–438. doi: 10.1128/jb.112.1.434-438.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ullah AHJ, Gibson DM. Extracellular phytase (E.C. 3.1.3.8) from Aspergillus ficuum NRRL 3135: purification and characterization. Prep Biochem. 1987;17:63–71. doi: 10.1080/00327488708062477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ullah AHJ. Aspergillus ficuum phytase: partial primary structure, substrate selectivity and kinect characterization. Prep Biochem. 1988;18:459–471. doi: 10.1080/00327488808062544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Hartingsveldt W, van Zeijl CM, Harteveld GM, Gouka RJ, Suykerbuyk ME, Luiten RG, van Paridon PA, Selten GC, Veeenstra AE, van Gorgon RF, van den Hondel CAMJJ. Cloning, characterization and overexpression of the phytase-encoding gene phyA of Aspergillus niger. Gene. 1993;127:187–194. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90620-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ehrlich KC, Montalbano BG, Mullaney EJ, Dischinger HC, Jr, Ullah AHJ. Identification and cloning of a second phytase gene (phyB) from Aspergillus niger (ficuum) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;195:53–57. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kostrewa D, Wyss M, D’arcy A, van Loon APGM. Crystal structure of Aspergillus niger pH 2,5 optimum acid phosphatase at 2,4 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1997;288:965–974. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang GQ, Dong XF, Wang ZH, Zhang Q, Wang HX, Tong JM. Purification, characterization, and cloning of a novel phytase with low pH optimum and strong proteolysis resistance from Aspergillus ficuum NTG-23. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:4125–4131. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piddington CS, Houston CS, Paloheimo M, Cantrell M, Miettinen-Oinonen A, Nevalainen JR. The cloning and sequencing of the genes encoding phytase (phy) and pH 2,5 optimum acid phosphatase (aph) from Aspergillus niger var. awamori. Gene. 1993;133:55–62. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90224-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mitchell DB, Vogel K, Weimann BJ, Pasamontes L, van Loon APGM. The phytase subfamily of histidine acid phosphatases: isolation of genes for two novel phytases from the fungi Aspergillus terreus and Myceliophthora thermophila. Microbiology. 1997;143:245–252. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-1-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shieh TR, Ware JH. Survey of microorganisms for the production of extracellular phytase. Appl Microbiol. 1968;16:1348–1351. doi: 10.1128/am.16.9.1348-1351.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martins MP, Martinez-Rossi NM, Sanches PR, Gomes EV, Bertolini MC, Pedersoli WR, Silva RN, Rossi A. The pH signaling transcription factor PAC-3 regulates metabolic and developmental processes in pathogenic fungi. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2076. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Papagianni M, Nokes SE, Filer K. Submerged and solid-state phytase fermentation by Aspergillus niger: effects of agitation and medium viscosity on phytase production, fungal morphology and inoculum performance. Food Technol Biotechnol. 2001;39:319–326. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vats P, Banerjee UC. Studies on the production of phytase by a newly isolated strain of Aspergillus niger van teigham obtained from rotten wood-logs. Process Biochem. 2002;38:211–217. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pires EBE, Freitas AJ, Souza FF, Salgado RL, Guimarães VM, Pereira FA, Eller MR. Production of fungal phytases from agroindustrial byproducts for pig diets. Sci Rep. 2019;9:9256. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45720-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Corrêa TLR, Queiroz MV, Araújo EF. Cloning, recombinant expression and characterization of a new phytase from Penicillium chrysogenum. Microbiol Res. 2015;170:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uchida H, Arakida S, Sakamoto T, Kawasaki H. Expression of Aspergillus oryzae phytase gene in Aspergillus oryzae RIB40 niaD−. J Biosci Bioeng. 2006;102:564–567. doi: 10.1263/jbb.102.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lassen SF, Breinholt J, Ostergaard PR, Brugger R, Bischoff A, Wyss M, Fuglsang CC. Expression, gene cloning and characterization of five novel phytases from four basidiomycete fungi: Peniophora lycii, Agrocybe pediades, a Ceriporia sp., and Trametes pubescens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:4701–4707. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.10.4701-4707.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang G-Q, Wu Y-Y, Ng T-B, Chen Q-J, Wang H-X. A phytase characterized by relatively high pH tolerance and thermostability from the Shiitake mushroom Lentinus edodes. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:540239. doi: 10.1155/2013/540239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu MJ, Wang HX, Ng TB (2011) Purification and identification of a phytase from fruity bodies of the winter mushroom, Flammulina velutipes. Afr J Biotechnol:17845–17852

- 65.Xu L, Zhang G, Wang H, Ng TB. Purification and characterization of phytase with a wide pH adaptation from common edible mushroom Volvariella volvacea (Straw mushroom) Indian J Biochem Biophys. 2012;1:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tan H, Tang X, Li T, Liu R, Miao Z, Huang Y, Wang B, Gan W, Peng Biochemical characterization of a psychrophilic phytase from an artificially cultivable morel Morchella importuna. J Microbiol Bioetechnol. 2016;27:2180–2189. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1708.08007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Özdemir SC, Uzel A. Bioprospecting of hot springs and compost in West Anatolia regarding phytase producing thermophilic fungi. Sydowia. 2020;72:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Potvin G, Ahmad A, Zhang Z. Bioprocess engineering aspects of heterologous protein production in Pichia pastoris: a review. Biochem Eng J. 2010;64:91–105. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ahmad M, Hirz M, Pichler H, Schwab H. Protein expression in Pichia pastoris: recent achievements and perspectives for heterologous protein production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:5301–5317. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5732-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ushasree MV, Vidya J, Pandey A. Extracellular expression of a thermostable phytase (phyA) in Kluyveromyces lactis. Proccess Biochem. 2014;49:1440–1447. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roongsawang N, Puseenam A, Kitikhun S, Sae-Tang K, Harnpicharnchai P, Ohashi T, Fujiyama K, Tirasophon W, Tanapongpipat S. A novel potential signal peptide sequence and overexpression of ER-resident chaperones enhance heterologous protein secretion in thermotolerant methylotrophic yeast Ogataea thermomethanolica. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2016;178:710–724. doi: 10.1007/s12010-015-1904-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xiong A-S, Yao Q-H, Peng R-H, Han P-L, Cheng Z-M, Li Y. High level expression of a recombinant acid phytase gene in Pichia pastoris. J Appl Microbiol. 2005;98:418–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhao D-M, Wang M, Mu X-J, Sun M-L, Wang X-Y. Screening, cloning and over expression of Aspergillus niger phytase (phyA) in Pichia pastoris with favourable characteristics. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2007;45:522–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2007.02216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Prondomkoy P, Tang K, Sornlake W, Harnpicharnchai P, Kobayashi RS, Ruanglek V, Upathanpreecha T, Vesaratchavest M, Eurwilaichitr L, Tanapongpipat S. Expression and characterization of Aspergillus thermostable phytases in Pichia pastoris. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;290:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Terpe K. Overview of bacterial expression systems for heterologous protein production: from molecular and biochemical fundamentals to commercial systems. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;72:211–222. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0465-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Phillipy BQ, Mullaney EJ. Expression of an Aspergillus niger (phyA) in Escherichia coli. J Agric Food Chem. 1997;45:3337–3342. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Delic M, Göngrich R, Mattanovich D, Gasser B. Engineering of protein folding and secretion strategies to overcome bottlenecks for efficient production of recombinant proteins. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21:414–437. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.5844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eichler J, Koomey M. Sweet new roles for protein glycosylation in prokaryotes. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25:662–672. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Erpel F, Restovic F, Arce-Johnson P. Development of phytase-expressing Chlamydomonas reinhardtii for monogastric animal nutrition. BMC Biotechnol. 2016;16:29. doi: 10.1186/s12896-016-0258-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen R, Xue G, Chen P, Yao B, Yang W, Ma Q, Fan Y, Zhao Z, Tarczynski MC, Shi J. Transgenic maize plants expressing a fungal phytase gene. Transgenic Res. 2008;17:633–673. doi: 10.1007/s11248-007-9138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Abid N, Khatoon A, Maqbool A, Irfan M, Bashir A, Asif I, Shahid M, Saeed A, Brinch-Pedersen H, Malik KA. Transgenic expression of phytase in wheat endosperm increases bioavailability of iron and zinc in grains. Transgenic Res. 2017;26:109–122. doi: 10.1007/s11248-016-9983-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang Y, Ye X, Ding G, Xu F. Overexpression of phyA and appA genes improves soil organic phosphorus utilization and seed phytase activity in Brassica napus. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Geetha S, Joshi JB, Kumar KK, Arul L, Kokiladevi E, Balasubramanian P, Sudhakar D. Genetic transformation of tropical maize (Zea mays L.) inbred line with a phytase gene from Aspergillus niger. 3 Biotech. 2019;9:208. doi: 10.1007/s13205-019-1731-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gontia I, Tantwai K, Rajput LPS, Tiwari S. Transgenic plants expressing phytase gene of microbial origin and their prospective applications as feed. Food Technol Biotechnol. 2012;50:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Giles CD, George TS, Brown LK, Mezeli M, Shand CA, Richardson AE, Mackay R, Wendler R, Darch T, Menezes-Blackburn D, Cooper P, Stutter MI, Lumsdom DG, Blackwell MSA, Wearing C, Zhang H, Haygarth PM. Linking the depletion or rhizosphere phosphorus to the heterologous expression of a fungal phytase in Nicotiana tabacum revealed by enzyme-labile P and solution 31P NMR spectroscopy. Rhizosphere. 2017;3:82–91. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hostetler HA, Collodi P, Devlin RH, Muir WM. Improved phytate phosphorous utilization by Japanese medaka transgenic for the Aspergillus niger phytase gene. Zebrafish. 2005;2:19–31. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2005.2.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Meidinger RG, Ajakaiye A, Fan MZ, Zhang J, Phillips JP, Forsberg CW. Digestive utilization of phosphorus from plant-based diets in the Cassie line of transgenic Yorkshire pigs that secrete phytase in the saliva. J Anim Sci. 2014;91:1307–1320. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang X, Li Z, Yang H, Liu D, Cai G, Li G, Mo J, Wang D, Zhong C, Wang H, Sun Y, Shi J, Zheng E, Meng F, Zhang M, He X, Zhou R, Zhang J, Huang M, Zhang R, Li N, Fan M, Yang J, Wu Z. Novel transgenic pigs with enhanced growth and reduced environmental impact. Elife. 2018;22:7. doi: 10.7554/eLife.34286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fugthong A, Boonyapakron K, Sornlek W, Tanapongpipat S, Eurwilaichitr L, Pootanakit K. Biochemical characterization and in vitro digestibility assay of Eupenicillium parvum (BCC17694) phytase expressed in Pichia pastoris. Protein Expr Purif. 2010;70:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.U Vasudevan M, Jaiswal AK, Krishna S, Pandey A. Thermostable phytase in feed and fuel industries. Bioresour Technol. 2019;278:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tang Z, Jin W, Sun R, Liao Y, Zhen T, Chen H, Wu Q, Gou L, Li C. Improved thermostability and enzyme activity of a recombinant phyA mutant phytase from Aspergillus niger N25 by directed evolution and site directed mutagenesis. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2018;108:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang G-Q, Wu Y-Y, Ng T-B, Chen Q-J, Wang H-X. A phytase characterized by relatively high pH tolerance and Thermostability from the shitake mushroom Lentinus edodes. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:540239. doi: 10.1155/2013/540239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Berka RM, Rey MW, Brown KM, Byun T, Klotz AV. Molecular characterization and expression of a phytase gene from the thermophilic fungus Thermomyces lanuginosus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4423–4427. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4423-4427.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Han Y, Wilson DB, Lei XG. Expression of an Aspergillus niger phytase gene (phyA) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1915–1918. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.1915-1918.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Han Y, Lei XG. Role of glycosylation in the functional expression of an Aspergillus niger phytase phyA in Pichia pastoris. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;364:83–90. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ma Z-Y, Pu S-C, Jiang J-J, Huang B, Fan M-Z, Li Z-Z. A novel thermostable phytase from the fungus Aspergillus aculeatus RCEF 4894: gene cloning and expression in Pichia pastoris. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;27:679–686. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ge F, Zhu L, Aang A, Song P, Li W, Tao Y, Du G. Recent advances in enhanced enzyme activity, thermostability and secretion by N-glycosylation regulation in yeast. Biotechnol Lett. 2018;40:847–854. doi: 10.1007/s10529-018-2526-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nielsen AVF, Nyffenegger C, Meyer AS. Performance of microbial phytases for gastric inositol phosphate degradation. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:943–950. doi: 10.1021/jf5050469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Böttcher D, Bornscheuer UT. Protein engineering of microbial enzymes. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13:274–282. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lutz S. Beyond directed evolution - semi-rational protein engineering and design. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2012;21:734–743. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jaenicke R, Schurig H, Beaucamp N, Ostendorp R. Structure and stability of hyperstable proteins: glycolytic enzymes from hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. Adv Protein Chem. 1996;48:181–269. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60363-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kumar K, Patel K, Agrawal DC, Khire JM. Insights into the unfolding pathway and identificationof thermally sensitive regions of phytase from Aspergillus niger by molecular dynamics simulations. J Mol Model. 2015;21:163. doi: 10.1007/s00894-015-2696-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Liao Y, Li C, Chen H, Wu Q, Shan Z, Han X. Site-directed mutagenesis improves the thermostability and catalytic efficiency of Aspergillus niger N25 phytase mutated by I44E and T252R. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2013;171:900–915. doi: 10.1007/s12010-013-0380-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Han N, Miao H, Yu T, Xu B, Yang Y, Wu Q, Zhang R, Huang Z. Enhancing thermal tolerance of Aspergillus niger PhyA phytase directed by structural comparison and computational simulation. BMC Biotechnol. 2018;18:36. doi: 10.1186/s12896-018-0445-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]