Abstract

The interest in lactic acid bacteria, including Lactobacillus plantarum NRRL B-4496, has increased in recent years as bio-preservatives, due to the production of secondary metabolites capable of inhibiting pathogenic bacteria. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the antimicrobial activity, cytotoxicity and the anti-inflammatory response of L. plantarum NRRL B-4496 cell-free supernatant (CFS). Furthermore, the CFS was fractionated by size exclusion chromatography using Sephadex G-25, and a minimal inhibitory volume test was determined against a panel of pathogenic bacteria. The cytotoxicity and the inflammatory activities of the fractions were evaluated using the human-derived THP-1 cell line. Results of this study indicates that CFS of L. plantarum NRRL B-4496 possesses antimicrobial protein compounds against the pathogen Listeria monocytogenes and showed no toxicity nor a pro-inflammatory response to human macrophages. The obtained results contribute to the development of novel bio-preservatives, L. plantarum cell-free supernatant or its fractions, with a potential use in the food industry.

Keywords: Lactobacillus plantarum, Protein fractions, Antimicrobial activity, Cytotoxicity, Inflammatory activity

Introduction

In recent years, a precipitated increase in drug-resistant infections to antibiotics has presented a serious challenge for researchers from different areas of study such as medicine, molecular biology, food science, and antimicrobials therapies. The ability of bacteria to develop different mechanism of resistance and the loss of efficacy of antibiotics/antimicrobials to inhibit pathogenic microorganisms bring out the urgent need to develop alternatives to evolve substances/compounds as control agents [1, 2].

Over the last decades, peptides have been studied for their antimicrobial activity and new development of natural antimicrobials and/or peptides (AMPs) with a vast spectrum of antiviral, antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-parasitic targets have been published [3–5].

In another perspective, there is a trend in the preference of consumers to choose fresh, preservative free, and less processed foods, which makes the research on natural antimicrobials relevant in order to replace current antimicrobials, while ensuring food safety. For this purpose, bio-preservatives such as essential oils, enzymes and microorganisms among others have been studied [6–8].

A good example is lactic acid bacteria (LAB) which have the ability to produce secondary metabolites that have been shown to possess antimicrobial activities such as organic acids, bacteriocins, hydrogen peroxide, reuterin (or 3-hydroxypropionaldehyde), diacetyl and ethyl alcohol among others [9–11]. Moreover, selected LAB has been recognized as safe for its traditional use in food fermentation process and was designed QPS (Qualified Presumption of Safety) with a direct application in food and pharmaceutical industries.

Previous studies have reported the antimicrobial activities of peptides isolated from lactobacilli. For example, peptides isolated from L. helveticus PR4 showed a broad spectrum of inhibition against Enterococcus faecium, Bacillus megaterium, Escherichia coli, Listeria innocua, Salmonella spp., Yersinia enterocolitica, and Staphylococcus aureus [12]. In another study, the peptide plantaricin K25 isolated from L. plantarum K25 showed antibacterial activity against Gram-positive and -negative bacteria [13].

To the best of our knowledge, no previous reports recognize bacteriocins or antimicrobial peptides/proteins from L. plantarum NRRL B-4496; moreover, previous work in our laboratory shows a strong antimicrobial activity of this Lactobacillus strain (data not shown). Therefore, following our program to identify novel peptides for use in food preservation, we aimed to study the antimicrobial activities of the cell-free supernatant (CFS) of L. plantarum NRRL B-4496. Moreover, we assessed the cytotoxicity and the inflammatory response of the CFS using a human macrophage model.

Materials and methods

Strains and media culture

L. plantarum NRRL B-4496 used in this study was provided by the Food Microbiology Laboratory strain collection of the Universidad de las Americas Puebla (Puebla, Mexico). Other bacterial strains used in this study were methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 700698), Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923), Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), Acinetobacter baumannii (ATCC BAA-747), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 14210), and Listeria monocytogenes (Scott A). Salmonella Typhimurium (ATCC 13311) was only used to test the antimicrobial activity of CFS fractions. The fungal strains Candida albicans (ATCC 10231), Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii (provided by Dr. Karen Bartlett, University of British Columbia, BC, Canada), Aspergillus fumigatus (ATCC 1022), and Trichophyton rubrum (ATCC 18758), representing human pathogenic fungi were used in this study. Bacterial strains were maintained in Mueller-Hinton broth (Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, MD) supplemented with 1.5% agar (Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, MD) at 4 °C. Fungal strains were maintained in Sabouraud broth (Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, MD) supplemented with 1.5% agar and incubated at 28 °C. Fungal spores suspensions were prepared according to published protocols [14].

Cell-free supernatant preparation

L. plantarum NRRL B-4496 was cultivated (106 CFU mL−1, plate count) in 30 mL of MRS broth (Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, MD) and incubated at 35 °C, 48 h. The CFS culture was obtained by centrifugation at 8000×g during 10 min (Marathon 21 K/R, Fisher Scientific, Germany), filter sterilized through 0.45 μm Millipore membrane filter, and CFS concentrated 10-fold by vacuum evaporation on a Buchi R-210/215 rotary evaporator (Buchi, Flawil, Switzerland) at 70 °C ± 1.0 °C and 25 cm Hg. Concentrated supernatants were lyophilized on a freeze-dryer (Labconco Corp., Kansas, MO).

Gel filtration chromatography of fractions

To obtain the fractions, CFSs were reconstituted in 1.5 mL PBS buffer and fractionated through a glass column (60 × 1.5 cm) filled with Sephadex G-25 (Pharmacia, Uppsala) in PBS with a final volume of (106 cm3). Gel filtration chromatography by size-exclusion was performed as described Hamilton [15]. The column was connected to a fraction collector FRAC-100 (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) and fourteen fractions of 1 mL each were collected with a flow rate of 200 μL min−1, in a total elution time of 1.2 h.

Protein quantification and molecular weight calculations

The protein amount in each fraction was determinate by the Bradford method. The binding of the dye with the proteins was evaluated by spectrophotometry at an absorbance of 595 nm [16]. A calibration curve using bovine serum albumin was used to calculate the protein concentrations.

Fractions 2, 3, 5 and 6 were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE, 12%) [17] in a Hoffer apparatus and 12 μL of the samples were loaded. Protein bands were silver stained, and molecular mass standards were obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA).

Minimal inhibitory volume

The minimum inhibitory volume (MIV) was defined as the minimum volume of CFS or its fractions at which no microbial growth was observed (no turbidity observed in the well). MIVs were determined by a microdilution assay. The CFS L. plantarum NRRL B-4496 and its fractions volumes of 2, 5 and 50 μg mL−1 were assayed in a final volume of 200 μL per well. Bacterial strains were grown at 37 °C for 18 h at 1×g and their densities were adjusted to an optical density of 0.05 at 600 nm (1 × 107 CFU mL−1). In the case of the filamentous fungi, 5 μL of a spore suspension (1 × 106 spores mL−1) were used as inoculum and incubated at 28 °C for 48 h. Amikacin (100 μg mL−1) or gentamicin (50 μg mL−1) (for bacteria), and amphotericin (100 μg mL−1) or terbinafine (125 μg mL−1) (for fungi) were used as positive controls. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

pH sensibility

CFS pH was measured and adjusted to pH 6.5 with a 40% NaOH (w/v) solution to test the antimicrobial activity of neutralized or not CFS.

Proteinase K test

The pH of the reconstituted CFS was adjusted to 6.5 with a 40% NaOH (w/v) solution. The proteinase digestion was performed by adding 3 μL of proteinase K (Fermentas, Hanover, MD) in a 200 μL well, the plate was incubated at 37 °C during 2 h. Afterwards, the antimicrobial activity of the neutralized-hydrolyzed CFS was determined by means of a minimum inhibitory volume test.

Cytotoxic assay

The cytotoxicity of the CFS fractions was evaluated using the human-derived monocytes THP-1 cell line (ATCC TIB- 202). We have implemented this model in our lab and the following publications are provided as an example: PDIM: 25417600, 27,794,508, 28,122,038, 31,111,047, and 31,205,934. The cytotoxic evaluation was performed following published protocols [18]. Briefly, 5 × 104 cells were dispensed per well in a 96-well plate with a final volume of 200 μL. CFS fractions were tested at a final volume of 100 μL. THP-1 cells exposed to hydrogen peroxide (10 μL of a 5% solution) were used as a positive control, whereas untreated cells were used as negative control. The analysis of the toxicity was performed with MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, Sigma). Experiments were performed in triplicate. Final concentrations of DMSO per well were always ≤1%.

Inflammatory assay

Inflammatory and anti-inflammatory assays were performed using activated THP-1 cells at a final density of 7.5 × 104 cells per well following published protocols [18]. Cells treated with 1% DMSO were considered as negative control (previous study showed DMSO suppresses the expression of many pro-inflammatory responses [19]), whereas 100 ng mL−1 of LPS from E. coli (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used as a positive control, since LPS stimulates immune responses by interacting with the membrane receptor CD14 to induce the generation of cytokines [20]. Experiments were carried out in triplicate and the final concentrations of DMSO per well were always ≤ 1%. Fractions were tested at a final volume of 100 μL, which was selected based on the survival of the cell in the cytotoxic experiments.

Statistical analysis

Statistical software Prism 8.2.1 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) was utilized to perform analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the mean differences were calculated using Tukey’s multiple comparison test (α = 0.05).

Results and discussion

Antimicrobial activities of CFS L. plantarum NRRL B-4496

The CFSs of L. plantarum NRRL B-4496 with pH neutralized or not, was tested against selected pathogenic bacteria and fungi (Table 1). Results showed that the non-neutralized CFS were more effective against methicillin-resistant S. aureus, S. aureus, and L. monocytogenes, followed by E. coli (Table 1) probably due to lactic acid antimicrobial activity. The molds and yeasts tested in this study (clinical pathogens) showed to be resistant to the CFSs. Interestingly, other studies have found a direct correlation between the antifungal activity and the lactic acid concentration. However, the microorganisms responded in a different way to antimicrobial compounds such as CFS due to their nature (wild type or collection strain), antimicrobial resistance, matrix, environmental conditions, among others. For example, the activity of CFSs from eighty-eight different L. plantarum strains isolated from different food matrices showed that lactic acid concentrations of 5 g L−1 to 25 g L−1, (which this variability depends on the incubation time of L. plantarum) were able to control the growth of several strains from the Spanish Type Culture Collection (CECT, Paterna, Spain): Aspergillus niger (CECT 2805), A. flavus (CECT 20802), Fusarium culmorum (CECT 2148), Penicillium roqueforti, P. expansum (CECT 2278), and P. chrysogenum (CECT 2669), and Cladosporium spp. (UFG 163, isolated from an oat based matrix). The researchers observed that higher production of lactic acid in the CFS (after 24 h of incubation) improved antifungal activity [21].

Table 1.

Antibacterial and antifungal activities of the CFS of L. plantarum NRRL B-4496 expressed as the minimum volume for inhibition (μg mL−1)

| Microorganism | Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native pH | Neutralized pH | Proteinase K | ||

| Bacteria (1 × 107 CFU mL−1) | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 700698 | 2 | R | R |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 | 2 | R | R | |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | 5 | R | R | |

| Listeria monocytogenes Scott A | 2 | 50 | R | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC BAA-747 | R | R | R | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 14210 | R | R | R | |

| Fungi | Candida albicans ATCC 10231 | R | R | R |

| (1 × 106 spores mL−1) | Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii | R | R | R |

| Trichophyton rubrum ATCC 18758 | R | R | R | |

| Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 1022 | R | R | R | |

R = maximal concentration tested 200 μl

Experiments were performed in triplicate

In our study, the neutralized CFS showing anti-Listeria activity appear to be related to the presence of peptides or proteins since the activity is abolished after treatment with proteinase K (Table 1). The antimicrobial activity detected for Listeria in CFS (neutralized or not) is lost when treated with the enzyme that hydrolyzed antimicrobial peptides or proteins.

In order to isolate the fractions responsible for the antibacterial activity, the CFS of the culture was subjected to fractionation through size exclusion chromatography. A total of fourteen fractions of 1 mL each were collected.

After testing all the fourteen fractions (upon pH neutralization), only the CFS fractions 2, 3, 5, and 6 showed antimicrobial activity against L. monocytogenes (Table 2) with a minimum volume of 50 μL. The rest of the CFS fractions showed no antibacterial activity against the tested bacteria.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial activity of the CFS fractions of L. plantarum NRRL B-4496

| Fraction | Listeria monocytogenes Scott A | Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 13311 | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 700698 | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 × 107 CFU mL−1 | 1 × 107 CFU mL−1 | 1 × 107 CFU mL−1 | 1 × 107 CFU mL−1 | 1 × 107 CFU mL−1 | |

| 1 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | – | + | + | + | + |

| 3 | – | + | + | + | + |

| 4 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5 | – | + | + | + | + |

| 6 | – | + | + | + | + |

| 7 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 8 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 9 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 10 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 11 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 12 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 13 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 14 | + | + | + | + | + |

Experiments were performed in triplicate

- No microbial growth observed (50 μg ml−1); + Microbial growth observed (200 μg mL−1)

In the literature, studies have reported that AMPs produced by LABs inhibited the growth of L. monocytogenes. For example, the bacteriocin LiN333 produced by L. casei isolated from Jianshui Cai (Chinese fermented food), inhibited the growth of L. monocytogenes at pH <10 [22], whereas plantaricin ZJ316 produced by L. plantarum ZJ316 showed antibacterial activities not only for Listeria spp., but also to a panel of Gram-negative and –positive bacteria [23]. Also, it is been reported that most of the bacteriocins studied are stable in acidic conditions but decreasing their activity when the medium is either in neutral or alkaline conditions [24]. In our study, we report that the activity of the protein-containing fractions was active upon neutralization of the pH.

The protein concentrations of the fractions were 157, 915, 328, and 196 μg mL−1 in fraction 2 (>100 kDa), 3 (~45 kDa), 5 (30–45 kDa), and 6 (15 kDa), respectively (Fig. 1). The rest of the collected fractions showed no presence of proteins.

Fig. 1.

Protein concentration in CFS fractions of L. plantarum NRRL B-4496. The protein concentration of CFS fractions obtained by exclusion chromatography was measured using the Bradford reagent. Protein concentrations were calculated according to a calibration curve of BSA

Other studies have reported that the antimicrobial peptide plantaricin ZJ316 had a molecular mass of 2.3 kDa, whereas pediocin LB-B1 (molecular masses of 2.5 and 6.5 kDa) produced by L. plantarum LB-B1 showed an effective bactericidal activity against L. monocytogenes 54,002 [25]. Tsai et al. [26] studied the antimicrobial peptide m2163 and m2386 isolated from L. casei ATCC 334, which showed the anti-proliferative activity on the human colorectal cancer cell line SW480.

Other works have reported that certain AMPs showed antibacterial activity against antimicrobial resistant bacteria. For example, although the methicillin resistant S. aureus Oxford was reported to be resistant to vancomycin, it was sensitive to nisin [27], whereas lacticin 3147 showed activity against twenty strains of vancomycin-resistant enterococci isolated from patients and obtained from the Antibiotic Resistance Monitoring and Reference Laboratory, Health Protection Agency (HPA), Colindale, UK), with minimal inhibitory concentration values between 1.9 and 7.7 mg L−1 [28].

Cytotoxicity and inflammatory activities of CFS fractions

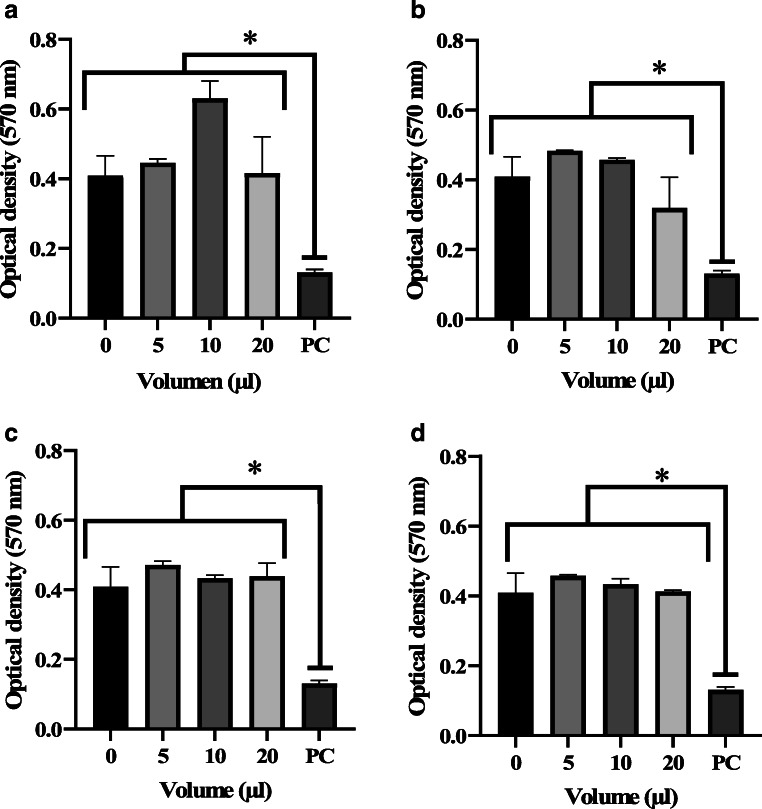

The cytotoxic activity was assayed on the human macrophage cell line THP-1. Results showed that all of the fractions that showed anti-Listeria activity were nontoxic to THP-1 cells (Fig. 2), suggesting a potential use in food preservation. Human-derived macrophages are a known model to assess cytotoxicity and inflammatory response upon exposure of the cells to different types of compounds. Macrophages are among the first cells to arrive when an injury or exposure to compounds occurs [18]. Another study reported that an exopolysaccharide isolated from the probiotic L. plantarum RJF4 showed no toxicity to the rat myoblast L6 cell line and have been proposed to use this polysaccharide as a food additive or for therapeutical applications [29]. Sentürk, Ercan and Yalcin [30] reported an IC50 value of the secondary metabolite produced by L. plantarum, isolated from animal sources, in the MCF-7 cell line of 0.0011 mg mL−1.

Fig. 2.

Cytotoxicity of CFS L. plantarum NRRL B-4496 fractions. The cytotoxicity of the (a) Fraction 2, (b) Fraction 3, (c) Fraction 5, and (b) Fraction 6; were assessed on human-derived macrophage THP-1 cell line using the MTT assay. PC = positive control. The data represent the mean ± the standard deviation from three independent experiments. Treatment groupings separated by an asterisk (*) are significantly different (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s test

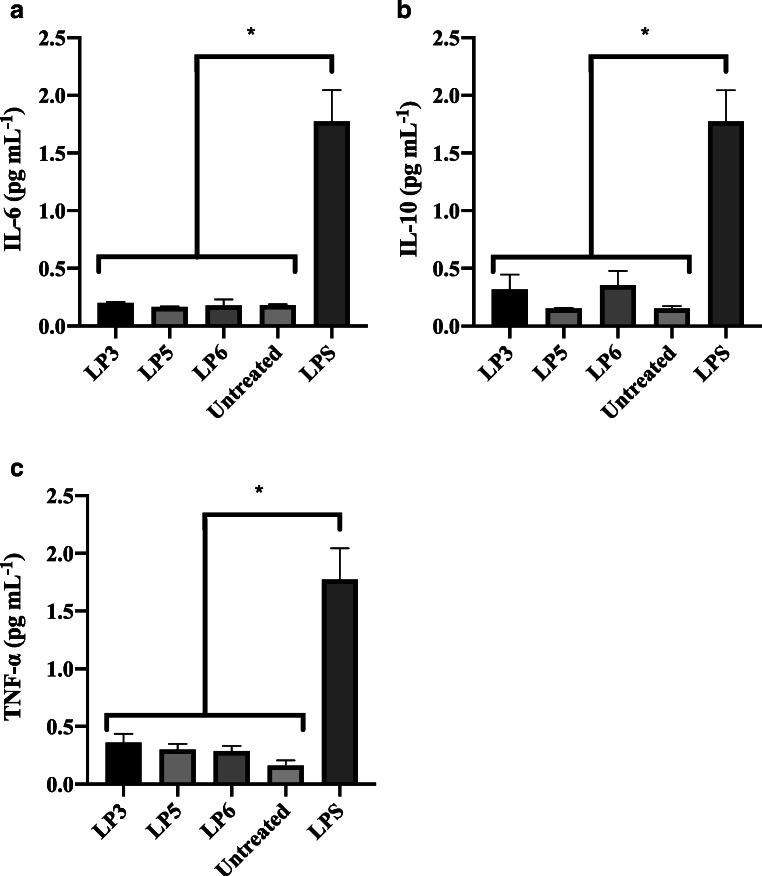

THP-1 cells are responsible for eliciting an inflammatory or anti-inflammatory response mediated by the secretion of cytokines [18]. In the case of the inflammatory activity, fractions were not able to elicit a pro-inflammatory response, as the levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α were not significantly different from the untreated control (negative control) (Fig. 3a and c). No anti-inflammatory activity was measured as the levels of IL-10 remained comparable to the untreated cells (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Immunological responses of CFS L. plantarum NRRL B-4496 fractions. The immunological response of the CFS fractions 3, 5 and 6 were assessed on human-derived macrophage THP-1 cell line using ELISA for (a) IL-6, (b) IL-10, and (c) TNF-α. LPS = lipopolysaccharide (positive control). The data represent the mean ± the standard deviation from three independent experiments. Treatment groupings separated by an asterisk (*) are significantly different (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s test

Other studies have reported anti-inflammatory activity of antimicrobial peptides. For example, the effect of the cationic antimicrobial peptide CEMA (cecropin-melittin hybrid) in macrophages treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS, inflammation inducer) was assessed. Results showed a selectively blockage of the genes induced by LPS, suggesting that the peptide has an anti-inflammatory activity [31]. Moreover, studies on the effect of nisin Z (a lantibiotic peptide) showed a modulation of the host inflammatory responses against S. aureus (ATCC 25293), Salmonella enterica sv. Typhimurium (SL1344), and E. coli (Xen-14, Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA, USA) using murine challenge models [32]. Lastly, peptides isolated from fermented milk inoculated with L. plantarum strains showed anti-inflammatory activity using the albumin inhibition denaturation test in vitro [33].

In another perspective, different strains of L. plantarum as a potential probiotic have been studied [34]. The authors observed that L. plantarum Ln4 from kimchi survive at pH 2.5 in the presence of 0.3% pepsin and 0.3% oxgall, showed intestinal cell adhesion to HT-29 cells and, did not produce harmful enzymes, as β-glucuronidase. As well, it has been reported that the daily intake of a capsule with L. plantarum (CECT 7527, CECT 7528, and CECT 7529, 1.2 × 109 CFU) after 12 weeks, lowered plasma total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C), and oxidized LDL-C (17.4, 17.6 and 15.6%, respectively; compared with the placebo group) in participants with hypercholesterolemia [35].

In conclusion, fractions containing proteins or peptides obtained upon fractionation of the crude extract of L. plantarum NRRL B-4496 inhibited the growth of L. monocytogenes. However, the fractions showing no protein levels did not show any antibacterial activity to any of the tested pathogenic microorganisms. The obtained results contribute to the development of a novel bio-preservative from L. plantarum CFS and its fractions, which constitute an important area of applications in the food industry. Some of the factors that should be considered in future studies are specificity, manufacturer cost, legislation governing their use, and a guideline for rational design.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the Antibody Engineering and Proteomics Facility, Immunity and Infection Research Centre, Vancouver, BC, Canada, by the National Council for Science and Technology (CONACyT) of Mexico and the Universidad de las Americas Puebla (UDLAP). Author Arrioja acknowledges financial support for her Ph.D. studies in Food Science from CONACyT and UDLAP.

Author contribution

D. Arrioja-Bretón performed research, analyzed data and wrote the paper, E. Mani-López contributed to analyze data and write the paper, H. Bach conceived the study and analyzed data, and A. López-Malo analyzed data and contributed to write the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest declared.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Shlaes DM, Gerding DN, John JF, Craig WA, Bornstein DL, Duncan RA, et al. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America and Infectious Diseases Society of America joint committee on the prevention of antimicrobial resistance: guidelines for the prevention of antimicrobial resistance in hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;18:275–291. doi: 10.1086/647610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman ND, Temkin E, Carmeli Y. The negative impact of antibiotic resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park CB, Kim HS, Kim SC. Mechanism of action of the antimicrobial peptide buforin II: buforin II kills microorganisms by penetrating the cell membrane and inhibiting cellular functions. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 1998;244:253–257. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang X, Wang Y, Liu L, Wei Y, Shang N, Zhang X, Li P. Two-peptide bacteriocin PlnEF causes cell membrane damage to Lactobacillus plantarum. BBA-Rev Biomembranes. 2016;1858:274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahar A, Ren D. Antimicrobial peptides. Pharma. 2013;6:1543–1575. doi: 10.3390/ph6121543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beristain-Bauza SC, Palou E, López-Malo A. Bacteriocinas: antimicrobianos naturales y su aplicación en los alimentos. TSIA. 2012;6:64–78. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muhialdin BJ, Hassan Z, Bakar FA, Saari N. Identification of antifungal peptides produced by Lactobacillus plantarum IS10 grown in the MRS broth. Food Control. 2016;59:27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mani-López E, Palou E, López-Malo A. Biopreservatives as agents to prevent food spoilage. In: Holban AM, Grumezescu AM, editors. Microbial contamination and food degradation. London, UK: Academic Press; 2018. pp. 235–270. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jay JM. Antimicrobial properties of diacetyl. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;44:525–532. doi: 10.1128/AEM.44.3.525-532.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piard JC, Desmazeaud M. Inhibiting factors produced by lactic acid bacteria. 2. Bacteriocins and other antibacterial substances. Lait. 1992;72:113–142. doi: 10.1051/lait:199229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arena MP, Silvain A, Normanno G, Grieco F, Drider D, Spano G, Fiocco D. Use of Lactobacillus plantarum strains as a bio-control strategy against food-borne pathogenic microorganisms. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:464. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minervini F, Algaron F, Rizzello CG, Fox PF, Monnet V, Gobbetti M. Angiotensin I-converting-enzyme-inhibitory and antibacterial peptides from Lactobacillus helveticus PR4 proteinase-hydrolyzed caseins of milk from six species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:5297–5305. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.9.5297-5305.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wen LS, Philip K, Ajam N. Purification, characterization and mode of action of plantaricin K25 produced by Lactobacillus plantarum. Food Control. 2016;60:430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Contreras Cárdenas AV, Hernández LR, Juárez ZN, Sánchez-Arreola E, Bach H. Antimicrobial, cytotoxic, and anti-inflammatory activities of Pleopeltis polylepis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;194:981–986. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamilton PB. Ion exchange chromatography of amino acids. Anal Chem. 1958;30:914–919. doi: 10.1021/ac60137a014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72(1–2):248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambrook HC. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juárez ZN, Bach H, Sánchez-Arreola E, Bach H, Hernández LR. Protective antifungal activity of essential oils extracted from Buddleja perfoliata and Pelargonium graveolens against fungi isolated from stored grains. J Appl Microbiol. 2016;120:1264–1270. doi: 10.1111/jam.13092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones R. Dimethylsulfoxide-controversy and current status-1981. JAMA. 1982;248(11):1369–1371. doi: 10.1001/jama.1982.03330110061032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meng F, Lowell CA. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced macrophage activation and signal transduction in the absence of Src-family kinases Hck, Fgr, and Lyn. J Exp Med. 1997;185(9):1661–1670. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russo P, Arena MP, Fiocco D, Capozzi V, Spano G. Lactobacillus plantarum with broad antifungal activity: a promising approach to increase safety and shelf-life of cereal-based products. Int J Food Microbiol. 2017;247:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ullah N, Wang XJ, Wu J, Guo Y, Ge HJ, Li TY, Khan S, Li ZX, Feng XC. Purification and primary characterization of a novel bacteriocin, LiN333, from Lactobacillus casei, an isolate from a Chinese fermented food. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2017;84:867–875. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.04.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen L, Gu Q, Li P, Li Y, Song D, Yang J. Purification and characterization of plantaricin ZJ316, a novel bacteriocin against Listeria monocytogenes from Lactobacillus plantarum ZJ316. J Food Prot. 2018;81:1929–1935. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-18-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sobrino-López A, Martín-Belloso O. Use of nisin and other bacteriocins for preservation of dairy products. Int. Dairy J. 2008;18:329–343. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2007.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie Y, An H, Hao Y, Qin Q, Huang Y, Luo Y, Zhang L. Characterization of an anti-Listeria bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus plantarum LB-B1 isolated from koumiss, a traditionally fermented dairy product from China. Food Control. 2011;22(7):1027–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2010.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai TL, Li AC, Chen YC, Liao YS, Lin TH. Antimicrobial peptide m2163 or m2386 identified from Lactobacillus casei ATCC 334 can trigger apoptosis in the human colorectal cancer cell line SW480. Tumor Biol. 2015;36(5):3775–3789. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-3018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brumfitt W, Salton MRJ, Hamilton-Miller JMT. Nisin, alone and combined with peptidoglycan-modulating antibiotics: activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;50:731–734. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piper C, Draper LA, Cotter PD, Ross RP, Hill C. A comparison of the activities of lacticin 3147 and nisin against drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus species. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64(3):546–551. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dilna SV, Surya H, Aswathy RG, Varsha KK, Sakthikumar DN, Pandey A, Nampoothiri KM. Characterization of an exopolysaccharide with potential health-benefit properties from a probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum RJF4. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2015;64:1179–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.07.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sentürk M, Ercan F, Yalcin S. The secondary metabolites produced by Lactobacillus plantarum downregulate BCL-2 and BUFFY genes on breast cancer cell line and model organism Drosophila melanogaster: molecular docking approach. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2019;85:33–45. doi: 10.1007/s00280-019-03978-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott MG, Rosenberger CM, Gold MR, Finlay BB, Hancock REW. An α-helical cationic antimicrobial peptide selectively modulates macrophage responses to lipopolysaccharide and directly alters macrophage gene expression. J Immunol. 2000;165:3358–3365. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kindrachuk J, Jenssen H, Elliott M, Nijnik A, Magrangeas-Janot L, Pasupuleti M, Thorson L, Ma S, Easton DM, Bains M, Finlay B, Breukink EJ, Georg-Sahl H, Hancock RE. Manipulation of innate immunity by a bacterial secreted peptide: Lantibiotic nisin Z is selectively immunomodulatory. Innate Immun. 2013;19:315–327. doi: 10.1177/1753425912461456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aguilar-Toalá JE, Santiago-López L, Peres CM, Peres C, Garcia HS, Vallejo-Cordoba B, González-Córdova AF, Hernández-Mendoza A. Assessment of multifunctional activity of bioactive peptides derived from fermented milk by specific Lactobacillus plantarum strains. J Dairy Sci. 2017;100:65–75. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-11846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Son SH, Jeon HL, Jeon EB, Lee NK, Park YS, et al. Potential probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum Ln4 from kimchi: evaluation of β-galactosidase and antioxidant activities. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2017;85:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.07.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fuentes MC, Lajo T, Carrion JM, Cune J. Cholesterol-lowering efficacy of Lactobacillus plantarum CECT 7527, 7528 and 7529 in hypercholesterolaemic adults. Br J Nutr. 2013;109(10):1866–1872. doi: 10.1017/S000711451200373X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]