Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to evaluate the ability of lapachones in disrupting the fungal multidrug resistance (MDR) phenotype, using a model of study which an azole-resistant Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant strain that overexpresses the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter Pdr5p.

Methods

The evaluation of the antifungal activity of lapachones and their possible synergism with fluconazole against the mutant S. cerevisiae strain was performed through broth microdilution and spot assays. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and efflux pump activity were assessed by fluorometry. ATPase activity was evaluated by the Fiske and Subbarow method. The effect of β-lapachone on PDR5 mRNA expression was assessed by RT-PCR. The release of hemoglobin was measured to evaluate the hemolytic activity of β-lapachone.

Results

α-nor-Lapachone and β-lapachone inhibited S. cerevisiae growth at 100 μg/ml. Only β-lapachone enhanced the antifungal activity of fluconazole, and this combined action was inhibited by ascorbic acid. β-Lapachone induced the production of ROS, inhibited Pdr5p-mediated efflux, and impaired Pdr5p ATPase activity. Also, β-lapachone neither affected the expression of PDR5 nor exerted hemolytic activity.

Conclusions

Data obtained indicate that β-lapachone is able to inhibit the S. cerevisiae efflux pump Pdr5p. Since this transporter is homologous to fungal ABC transporters, further studies employing clinical isolates that overexpress these proteins will be conducted to evaluate the effect of β-lapachone on pathogenic fungi.

Keywords: Fluconazole, Lapachone, Multidrug resistance, Yeast

Introduction

Infections caused by azole-resistant fungi are a matter of extreme concern to public health, due to the high mortality associated with them, mainly in immunocompromised individuals [1]. Nevertheless, a low number of drugs is available to treat fungal infections, and there are several disadvantages related to their use, such as the increasing incidence of resistance to azole and echinocandin drugs, and the toxicity induced by amphotericin B [2].

The multidrug resistance (MDR) phenotype is majorly responsible for the failure of antifungal treatments. It confers to the microorganism a high degree of resistance to structurally and functionally unrelated compounds [3]. In fungi, the main MDR mechanism relies on the overexpression of efflux transporters within the plasma membrane [4]. These proteins, also called efflux pumps, extrude the drugs from the cell, avoiding them to reach the intracellular concentration required to a successful antifungal activity [5]. The co-administration of an antifungal agent, such as fluconazole, and a substance capable of inhibiting efflux pumps would preclude antifungal resistance, therefore ensuring the proper outcome of the treatment [6].

MDR transporters related to antifungal resistance belong mainly to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily, which consists of primary active transporters that use ATP hydrolysis as an energy source for the transport of substances against a concentration gradient [7]. Besides Candida spp., Cryptococcus spp., and Aspergillus spp., MDR transporters are also found in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [8]. Moreover, S. cerevisiae MDR transporters are homologous to efflux pumps of pathogenic fungi. For example, the ABC pumps CaCdr1p [9] and CaCdr2p [10], the major Candida albicans MDR transporters, are homologous to S. cerevisiae Pdr5p, Snq2p, and Yor1p. The high similarity shared by these proteins enables the use of S. cerevisiae as a model of study of antifungal resistance in pathogenic fungi [11].

Lapachones are natural naphthoquinones that possess several pharmacological activities [12, 13]. In a previous work, our group aimed to study the effect of lapachones on C. albicans virulence factors. It was observed that β-lapachone and α-nor-lapachone were able to inhibit C. albicans growth, yeast-to-hyphae transition, biofilm formation, and cell wall mannoprotein expression [14].

Considering the relevance of fungal infections caused by resistant strains, the urgent need of discovering new therapeutic options, and the in vitro effectiveness of lapachones against C. albicans growth and virulence factors, the aim of this study was to evaluate the ability of lapachones in inhibiting Pdr5p-mediated antifungal resistance, using a model of study which an azole-resistant Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant strain that overexpresses this transporter.

Materials and methods

Strains and culture conditions

In this study, two mutant strains of S. cerevisiae were used. The first strain, namely, AD124567 (Pdr5p+), overexpresses Pdr5p, while the genes encoding the Pdr3p regulator and the other five ABC transporters (Yor1p, Snq2p, Pdr10p, Pdr11p, and Ycf1p) have been deleted. The second one, namely, AD1234567 (Pdr5p−), had all the six genes related to ABC transporters deleted, and also the gene that encodes the Pdr5p transporter [15]. Consequently, Pdr5p+ strain shows fluconazole resistance, while Pdr5p− strain is sensitive to this antifungal agent. Both strains were grown in yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) medium (2% glucose, 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone) at 30 °C with agitation and were harvested in the exponential phase of growth whenever experiments were about to be performed. At growth experiments, cells were incubated in the presence of β-lap for 48 h. In previous studies, it was observed that 90 min is a suitable incubation time considering the functioning of Pdr5p, and then, it was chosen to be used at the subsequent assays using intact cells. At experiments employing purified membranes and erythrocytes, 60 min of incubation time was chosen because it is optimal to observe Pdr5p ATPase activity and hemolytic effects, respectively. Cellular concentrations were evaluated by optical density measurements (600 nm) and expressed as “cells/ml”.

Chemicals

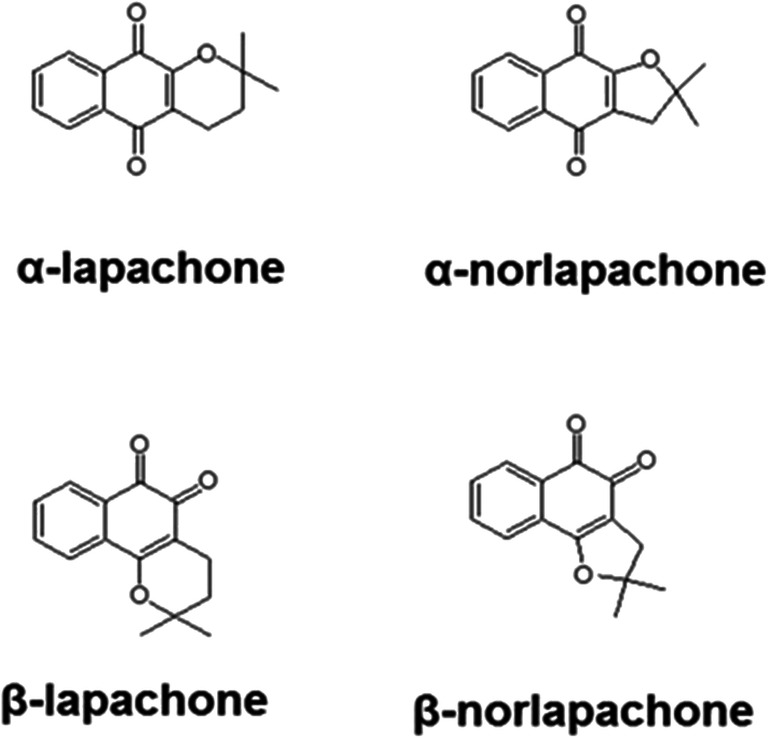

Fluconazole was obtained commercially from the university pharmacy (UFJF, Juiz de Fora—MG, Brazil). Fluconazole stock solutions were prepared in distilled water, sterilized by filtration (0.22 μm), and maintained at − 20 °C. α-Lapachone (α-lap), α-nor-lapachone (α-nor), β-lapachone (β-lap), and β-nor-lapachone (β-nor) (Fig. 1) were synthesized by the Laboratory of Heterocyclic Chemistry from the Institute of Natural Products Research (IPPN/UFRJ) and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma-Aldrich®, St. Louis, USA, D4540) to a final concentration of 10 mg/ml [16]. 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) (D6883), Nile red (19193), ascorbic acid (200.06), JumpStart Taq DNA Polymerase (D9307), SYBR Green (S9430), PCR Reference dye (R4526), and dNTP set (GE-28-4065) were also purchased from Sigma-Aldrich®, and stock solutions were prepared in distilled water and stored at 2–8 °C.

Fig. 1.

Structure of the compounds tested in this study: α-lapachone; α-nor-lapachone; β-lapachone; β-nor-lapachone

Antifungal susceptibility test

The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined according to the M27-A3 methodology for broth microdilution from CLSI [17] with slight modifications. Briefly, 2 × 104 cells/ml of Pdr5p+ strain were inoculated into YPD medium and incubated at 30 °C for 48 h with agitation (75 rpm), in the presence of serial concentrations (100–6.25 μg/ml) of lapachones. Cell growth was measured using a microplate reader at 600 nm (Fluostar Optima, BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany).

Checkerboard assay

The ability of lapachones to enhance fluconazole activity was evaluated through the checkerboard assay as described elsewhere [18] with slight modifications. Briefly, 2 × 104 cells/ml of Pdr5p+ strain were inoculated into YPD medium and incubated at 30 °C for 48 h with agitation (75 rpm), in the presence of combinations of serial concentrations of lapachones (100–6.25 μg/ml) and fluconazole (500–31.25 μg/ml). Cell growth was measured using a microplate reader at 600 nm (Fluostar Optima, BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany). The interaction between lapachones and fluconazole was evaluated by the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) model. The FICI is defined as the sum of the FIC of each drug, while FIC is the ratio MIC in combination/MIC alone. Synergistic, additive, indifferent, and antagonistic interactions were defined by a FICI < 0.5, 0.5–1.0, 1.0–4.0, or > 4.0, respectively.

Spot assay

The spot assay was performed as described elsewhere [19]. Briefly, 5-fold serial dilutions of 6 × 105 cells/ml of Pdr5p+ were spotted onto YPD agar plates in the presence or absence of 125 μg/ml fluconazole, 12.5 μg/ml β-lap, and 25 mM ascorbic acid. Then, plates were incubated at 30 °C for 48 h and photographed.

Reactive species oxygen measurement

The fluorescent probe DCFH-DA was used in order to assess the production of reactive species oxygen (ROS) induced by β-lap and the combination of β-lap/fluconazole [20]. Briefly, 107 cells/ml of Pdr5p+ strain were incubated at 30 °C for 90 min in the presence of 100 μg/ml β-lap, 125 μg/ml fluconazole, 100 μg/ml β-lap + 125 μg/ml fluconazole, and 100 μg/ml β-lap + 125 μg/ml fluconazole + 25 mM ascorbic acid. Untreated cells were used as the negative control. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000g for 3 min and pellets were resuspended in PBS containing 10 μM DCFH-DA and incubated for 15 min in darkness. Fluorescence was measured at 485/538 nm (excitation/emission) (Fluostar Optima, BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany), and results were expressed as mean intensity fluorescence.

Nile red accumulation assay

The effect of β-lap on the efflux activity of Pdr5p was assessed as described elsewhere [21], with slight modifications. Briefly, Pdr5p+ cells (107 cells/ml) were harvested by centrifugation at 5000g for 3 min and washed twice with cold PBS 10 mM at pH 7.2. Afterward, cells were incubated in a 96-well black polystyrene microplate for 60 min at 30 °C in the presence of 100 μg/ml β-lap, followed by the addition of 7 μM of Nile red and incubation at 30 °C for 30 min. Lastly, cells were resuspended in PBS containing 0.2% glucose and incubated for 30 min at 30 °C. The Pdr5p− strain was used as a blank control. Fluorescence was measured at 485/538 nm (excitation/emission) (Fluostar Optima, BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany), fluorescence of the blank systems was discounted, and results were expressed in comparison to the untreated system.

Preparation of plasma membranes

S. cerevisiae plasma membranes were obtained from mutant strain Pdrp5+ and from the null mutant Pdr5p− as previously described elsewhere [22]. Briefly, cells in the exponential phase of growth were harvested and washed with 10 mM sodium azide. Then, yeast cell wall was digested and differential centrifugation was performed in order to remove contaminants (4500g for 10 min, 12,000g for 12 min, and 20,000g for 40 min, respectively). Plasma membrane preparations were stored in liquid nitrogen and thawed immediately prior to use in the Pdr5p ATPase activity assays.

ATPase activity

The effect of β-lap on the ATPase activity of Pdr5p was evaluated by incubating membranes containing Pdr5p (0.013 mg/mL final concentration) in a 96-well plate at 37 °C for 60 min in a reaction medium containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 4 mM MgCl2, 75 mM KNO3, 7.5 mM NaN3, 0.3 mM ammonium molybdate, and ATP (1 mM, 2 mM, or 3 mM) in the presence of different concentrations of the compound (100–6.25 μg/ml). After incubation, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 1% SDS [23], and the amount of released inorganic phosphate (Pi) was measured through the Fiske and Subbarow method [24]. Briefly, 100 μL of ammonium molybdate was added to the wells, and inorganic phosphate released from ATP hydrolysis was measured spectrophotometrically at 660 nm (Fluostar Optima, BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany). Preparations containing plasma membranes obtained from the null mutant strain AD1234567 (Pdr5p− membranes) were used as controls, and the difference between the ATPase activity of the Pdr5p+ and Pdr5p− membranes represents the ATPase activity that is mediated by Pdr5p. A Lineweaver-Burk plot was designed in order to assess the type of inhibition promoted by β-lap.

Mitochondrial membrane potential measurement

The effect of β-lapachone on the mitochondrial membrane potential of Pdr5p+ strain was evaluated as described by Hwang et al. [25], with slight modifications. Briefly, 107 cells/ml of Pdr5p+ strain were incubated at 30 °C for 90 min in the presence of 100 μg/ml β-lap and 10 μM sodium azide. Untreated cells were used as negative control. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000g for 3 min and pellets were resuspended in PBS containing 2.5 μg/ml JC-1 and incubated for 15 min in darkness. Fluorescence was measured at 485/530 nm (excitation/emission) and at 485/590 nm (SpectraMax i3x, Molecular Devices, CA, USA), and results were expressed as the JC-1 fluorescence ratio (590 nm/530 nm).

RT-PCR

Quantification of mRNA expression levels was performed as previously described [26]. Briefly, Pdr5p+ cells (107 cells/ml) were incubated in the presence or absence (calibrator system) of 100 μg/ml β-lap, 125 μg/ml fluconazole, and 100 μg/ml β-lap + 125 μg/ml fluconazole for 90 min at 30 °C. Then, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000g for 3 min and washed twice with PBS 10 mM pH 7.2. The pellet was resuspended in an RNA lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0; 0.5 M EDTA; 0.5% SDS; 1% 2-mercaptoethanol), mixed for 30 s and incubated at 65 °C for 1 h. Afterwards, RNA was extracted using a homemade TRIzol Reagent (38% phenol pH 4.3, 0.8 M guanidine thiocyanate, 0.4 M ammonium thiocyanate, 0.1 M sodium acetate pH 5.0, 5% glycerol) [27]. From each sample, 1.0 μg of total RNA was subjected to RNase-free DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) treatment, and complementary DNA was synthesized using the high-capacity cDNA reverse. Quantitative PCR was performed using a SYBR Mix, consisting of 20 mM Tris, 50 mM potassium chloride, 5 mM magnesium chloride, 5 μL JumpStart Taq DNA polymerase, 0.5× SYBR Green, and 200 nM dNTP. Gene expression profile was evaluated using the StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) under default parameters. The 2−ΔΔCT method was adopted to calculate the relative abundance of the samples employing TFC1 as a housekeeping gene to normalize the expression of PDR5 gene. The following real-time PCR primers (0.4 μM) were used: PDR5F: 5′-CCCAAGTGCCATGCCTAGAT-3′; PDR5R: 5′-CGTTAGCAACACCAACAGCC-3′; TFC1F: TGGATGACGTTGATGCAGAT-3′; TFC1R: 5′-GCTCGCTTTTCATTGTTTCC-3′.

Human erythrocyte viability

The effect of β-lap on human erythrocyte viability was assessed as described elsewhere [18]. Cells were washed three times and resuspended in PBS to a final of concentration of 2% v/v. Then, cells were incubated in the presence of different concentrations of β-lap (128–0.5 μg/ml) for 60 min at 37 °C. Afterward, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3000g for 5 min and 100 μl of supernatant was transferred to the wells of a 96-well microplate. The absorbance of hemoglobin released from human erythrocytes was measured at 540 nm (Fluostar Optima, BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany). Controls of 100% and 0% hemolysis were performed by incubating the cells in PBS in the presence or absence of 1% Triton X-100, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were performed at least three times, and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Data were analyzed by Student’s t test, and P values lower than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Antifungal susceptibility test

While α-nor and β-lap completely inhibited S. cerevisiae growth at 100 μg/ml, α-lap inhibited fungal growth in 28% at 100 μg/ml. Moreover, β-nor did not present antifungal activity against Pdr5p+ cells (Fig. 2). Furthermore, Fig. 2 shows that the inhibition of cell growth by α-lap, α-nor, and β-lap was dose-dependent.

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of the growth of Pdr5p+ cells in the presence of the tested compounds. Cells were grown in the presence of α-lapachone, α-nor-lapachone, β-lapachone, and β-nor-lapachone at 6.25–100 μg/ml at 37 °C for 48 h. Cell growth was measured spectrophotometrically (600 nm). Data represent mean ± standard error of three independent experiments. Black circle for α-lapachone. Whit circle for α-nor-lapachone. Inverted black triangle for β-lapachone. White triangle for β-nor-lapachone. *p < 0.05

Checkerboard assay

Data obtained by checkerboard assay are summarized in Table 1. Combining α-lap, α-nor, or β-nor with fluconazole did not enhance the antifungal activity of the compounds, and FICI values ranged from 1.5 to 2.0, indicating no interaction. Nevertheless, the association between β-lap and fluconazole promoted a 4-fold decrease in their MIC values, with a FICI of 0.5, indicating synergism.

Table 1.

Checkerboard assays of S. cerevisiae mutant strain overexpressing the multidrug efflux pump Pdr5p

| Lapachone (μg/ml) | Fluconazole (μg/ml) | FICI | Outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC a | MIC c | FIC | MIC a | MIC c | FIC | |||

| α-Lap | > 100 | > 100 | 1 | 500 | 500 | 1 | 2 | I |

| α-Nor | 100 | 50 | 0.5 | 500 | 500 | 1 | 1.5 | I |

| β-Lap | 50 | 12.5 | 0.25 | 500 | 125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | S |

| β-Nor | > 100 | > 100 | 1 | 500 | 500 | 1 | 2 | I |

MIC a, MIC of compound alone; MIC c, MIC of compound combined; FIC, fractional inhibitory concentration; FICI, fractional inhibitory concentration index; I, indifferent; S, synergistic

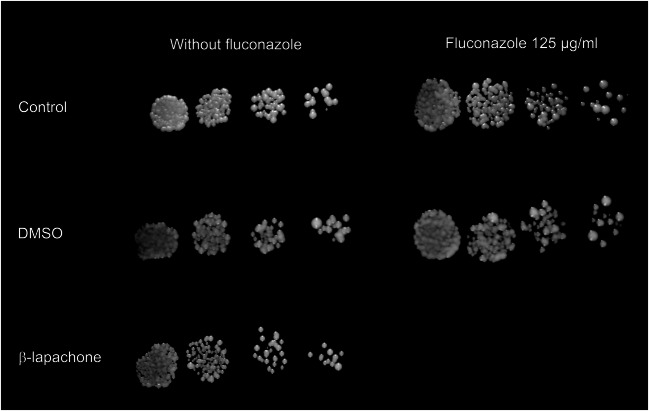

Spot assay

The combined activity between β-lapachone and fluconazole was also evaluated through the spot assay. Results presented in Fig. 3 show that Pdr5p+ cells grew in the absence and presence of 125 μg/ml fluconazole (positive control). Cells were able to grow at all yeast concentrations tested. On the other hand, the combination of β-lap and fluconazole completely inhibited cell growth.

Fig. 3.

Combined effect of β-lapachone and fluconazole on the growth of Pdr5p+ cells in solid media through spot assay. Serial 5-fold dilution cells were spotted onto YPD agar in the presence or absence of 125 μg/ml fluconazole, 0.125% DMSO, and 12.5 μg/ml β-lapachone. Combining fluconazole and β-lapachone resulted in the complete inhibition of Pdr5p+ cell growth

Reactive species oxygen measurement

Pdr5p+ cells produced a basal concentration of ROS after incubation in the absence of any substances (Fig. 4a). Treatment with 125 μg/ml fluconazole did not change significantly the fluorescence emitted by DCFH-DA, indicating that this antifungal agent did not stimulate ROS production by Pdr5p+ cells. Nonetheless, treatment with 100 μg/ml β-lap led to an approximately 2-fold increase of ROS concentration. Combining β-lap with fluconazole did not augment the ROS production in comparison with treatment with β-lap alone. Ascorbic acid significantly diminished ROS production, being used as a negative control. Moreover, combining β-lap, fluconazole and ascorbic acid promoted cell growth comparable with a positive control (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Effect of β-lapachone and fluconazole alone and in combination on ROS production by Pdr5p+ cells. a ROS production after treatment with 125 μg/ml fluconazole was comparable with control. Treatment with 100 μg/ml β-lapachone increased ROS production. Combining β-lap with fluconazole did not enhance ROS production in comparison with treatment with β-lapachone alone. Ascorbic acid significantly diminished ROS production, being used as a negative control. *p < 0.05 in comparison with untreated system. b Combined effect of ascorbic acid, β-lapachone, and fluconazole on the growth of Pdr5p+ cells in solid media through spot assay. Serial 5-fold dilution cells were spotted onto YPD agar in the presence or absence of 125 μg/ml fluconazole, 25 mM ascorbic acid, 0.125% DMSO, and 12.5 μg/ml β-lapachone. Combining 100 μg/ml β-lapachone, 125 μg/ml fluconazole, and 25 mM ascorbic acid promoted cell growth comparable to the positive control

In this methodology, β-lap was used at a concentration (100 μg/ml) higher than its MIC in combination with fluconazole, due to the increase in the number of yeasts used. Toxicity was not observed when 107 cells/ml was incubated with 100 μg/ml β-lap at 30 °C for 48 h, a period higher than the used in the present methodology (data not shown).

Nile red accumulation assay

Nile red is a highly fluorescent phenoxazine derivative and is also a substrate for MDR transporters. In a cell where efflux pumps are either blocked or low expressed, Nile red incorporates into the cytoplasm and stains it red. However, a cell that overexpresses MDR transporters extrudes Nile red from the intracellular environment, diminishing fluorescence. Treatment of Pdr5p+ cells with 100 μg/ml β-lap increased Nile red accumulation in 79.4%, in comparison with the untreated cells, as shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Assessment of Pdr5p activity by Nile red accumulation assay. Pdr5p+ cells were incubated in the presence or absence of 100 μg/ml β-lapachone for 60 min at 30 °C. Then, cells were loaded with Nile red, and the transporter was activated by adding 0.2% glucose. Treatment of Pdr5p+ cells with β-lapachone inhibited Nile red efflux by 79.4%. *p < 0.05

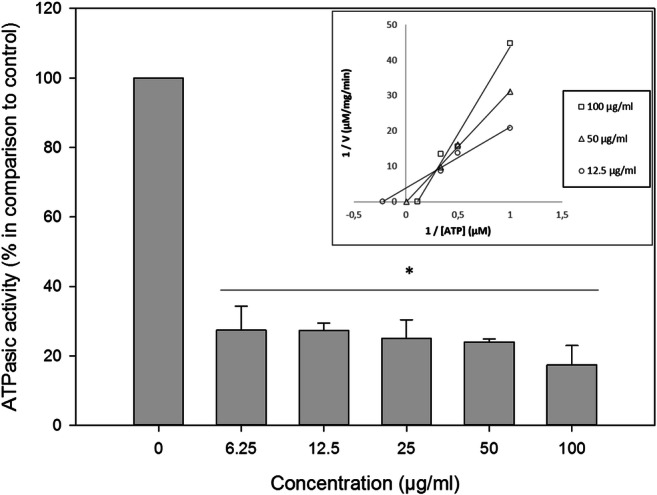

ATPase activity

Since Pdr5p is an ATP-binding cassette protein, it uses ATP hydrolysis as an energy source to extrude drugs from the cell. Thus, inhibiting ATPase activity of Pdr5p would preclude its ability to transport substances. At concentrations ranging from 6.25 to 100 μg/ml, β-lap inhibited Pdr5p ATPase activity by 72.6–82.5% (Fig. 6a). The Lineweaver-Burk plot shows that the effect of β-lap on Pdr5p ATPase activity resulted from a mixed inhibition (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

The effect of β-lapachone on the ATPase activity of Pdr5p was evaluated by incubating membranes containing Pdr5p in the presence of different concentrations of the compound (100–6.25 μg/ml). β-Lapachone inhibited Pdr5p ATPase activity by 72.6–82.5%. The Lineweaver-Burk plot shows that the effect of β-lap on Pdr5p ATPase activity occurred due to a mixed inhibition (inset). *p < 0.05

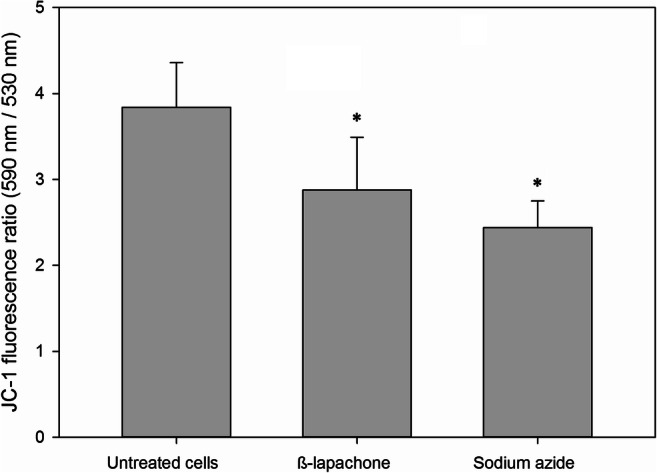

Mitochondrial membrane potential measurement

ATP production by mitochondria is dependent of the mitochondrial membrane potential. Since ATP is the energy source of ABC proteins, disrupting mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) would jeopardize ATP production, avoiding the functioning of Pdr5p. At 100 μg/ml, β-lap reduced MMP by 25%, while sodium azide decreased MMP by 37% (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Mitochondrial membrane potential in the presence of β-lapachone was assessed by JC-1 labeling. β-Lapachone at 100 μg/ml reduced MMP by 25%, while sodium azide decreased MMP by 37%. *p < 0.05

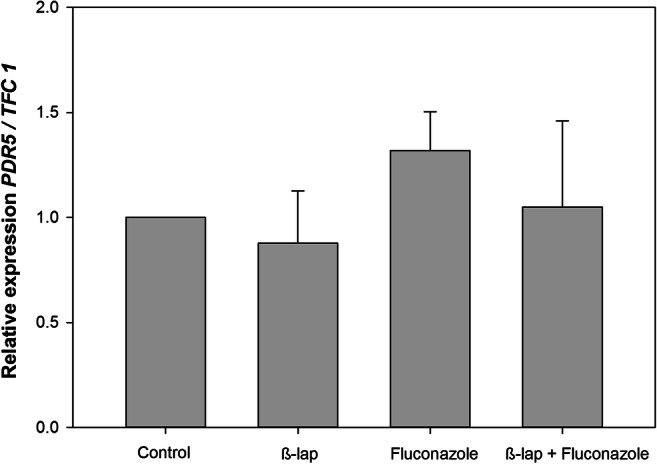

RT-PCR

Besides the impairment of the efflux pump activity, another strategy that could be used to overcome drug resistance is the inhibition of gene transcription. In order to verify this hypothesis, the RT-PCR assay was performed. Neither β-lap and fluconazole alone nor the combination between these drugs affected the transcription of the PDR5 gene (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

The influence of β-lapachone alone or in combination with fluconazole on PDR5 mRNA expression of Pdr5p+ cells was assessed by RT-PCR. TFC1 was used as a housekeeping gene and the untreated cells as a reference sample. The relative expression level of mRNA was calculated using the ΔΔCT method. Values represent mean + SD of three independent experiments. One hundred micrograms per milliliter of β-lapachone, 125 μg/ml fluconazole, and 100 μg/ml β-lapachone + 125 μg/ml fluconazole did not exert any significant effect on PDR5 gene expression

Human erythrocyte viability

Treatment of human erythrocytes with β-lap at 128 μg/ml produced hemolysis (3.77%) comparable with PBS (3.56%) and DMSO at 1.28% (5.23%) (Fig. 9), denoting to a non-hemolytic activity of the compound.

Fig. 9.

Evaluation of β-lapachone toxicity against human erythrocytes. A human erythrocyte suspension (0.5% v/v) was incubated in the presence of serial concentrations of β-lapachone (128–0.5 μg/ml) for 60 min, and the absorbance of released hemoglobin was measured at 540 nm. Controls of 100% and 0% hemolysis were performed by incubating the cells in PBS in the presence or absence of 1% Triton X-100, respectively. DMSO (1.28%) was also used as control. β-Lapachone showed toxicity comparable with PBS and DMSO. *p < 0.05

Discussion

The research focusing on the discovery of new antifungal therapies has largely increased in the past decade, due to high mortality caused by invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised individuals [28, 29]. The present status of fungal infection epidemiology is the consequence of the remarkable ability of fungi to acquire resistance to antifungal agents. Then, overcoming fungal resistance mechanisms would be a promising approach to cope with infections caused by MDR microorganisms [30].

Since the main MDR mechanism of pathogenic fungi is related to the overexpression of efflux transporters along the plasma membrane, inhibiting these proteins could avoid the extrusion of the antifungal agent and hence allow its antifungal activity [31]. Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate whether lapachones, natural products with known antifungal activity, are able to enhance the antifungal activity of fluconazole through the inhibition of Pdr5p, a S. cerevisiae MDR transporter.

Firstly, the effect of lapachones on Pdr5p+ cells growth was evaluated through a microdilution technique. A dose-dependent effect of β-lap on the growth of Pdr5p+ strain was observed, with a MIC value of 50 μg/ml. Menacho-Márquez and Murguía [32] assessed the effect of β-lap on the growth of a wild-type S. cerevisiae strain and have also observed a dose-dependent profile; however, the highest concentration employed in this study was 20 μg/ml. At this concentration, a reduction of 60% on S. cerevisiae growth was observed, while we obtained an 80% growth reduction at 25 μg/ml.

The greater effect of α-nor and β-lap against yeast growth was reported by our group in a previous study using a fluconazole-resistant C. albicans strain [14]. Nevertheless, α-lap and β-nor have also shown antifungal activity against C. albicans, which was not observed in the present study against S. cerevisiae cells. Moreover, Pdr5p+ cells were less susceptible to lapachones than the aforementioned C. albicans strain. A study using a higher number of C. albicans and S. cerevisiae strains must be performed in order to compare the susceptibility of these two microorganisms to lapachones and confirm this finding.

In order to screen the compounds for use on the subsequent methodologies, the interaction between lapachones and fluconazole, a well-known antifungal drug, was evaluated by the checkerboard method. Only β-lap presented synergism with fluconazole against Pdr5p+ cellular growth. For this reason, this compound was selected and used in the following assays. This is the first report regarding the synergic effect between β-lap and an antifungal agent. The interaction between β-lap and antimicrobial drugs has been characterized in other organisms, such as Mycobacterium sp. [33] and Staphylococcus aureus [34], but the mechanisms involved were not yet clarified.

According to Ramos-Pérez et al. [35], the antifungal activity of β-lap is related to its ability to induce ROS production, since a yap1Δ mutant strain was hypersensitive to the quinone at 30 μM. Anaissi-Afonso et al. [36] have also observed that β-lap and derivatives at 10–100 μM exert their antifungal activity through oxidative stress and mitochondrial disfunction. On the other hand, Menacho-Márquez et al. [37] observed that pre-incubation with dicoumarol did not affect the antifungal toxicity of β-lap, indicating that ROS production is not the mechanism responsible for the toxicity of β-lap against S. cerevisiae. In this study, it was observed that combining β-lap and fluconazole did not enhance ROS production. Nonetheless, ascorbic acid prevented the inhibitory effect of the combination β-lap and fluconazole on S. cerevisiae growth, pointing to the essential role of ROS on the synergism between β-lap and fluconazole. Li et al. [38] observed that osthole, a prenylated coumarin obtained from the Chinese herb Cnidii fructus, presented a synergistic effect with fluconazole against the growth of fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains. The mechanism involved in this action may be related to ROS production, since combining these substances led to the upregulation of oxidation-reduction genes. Interestingly, unlike β-lap, osthole combined with fluconazole promoted a threefold increase of intracellular ROS production (in comparison with osthole alone), reinforcing the participation of ROS on the synergistic interaction between these compounds.

Pdr5p+ strain was used in this study because its azole resistance is a consequence of the overexpression of Pdr5p, an ABC transporter related to the MDR phenotype. In order to unveil whether the combined activity of β-lap and fluconazole occurs due to the inhibition of Pdr5p function, a methodology using Nile red was employed [39]. In this study, it was observed that β-lap significantly increased Nile red fluorescence within the cells, meaning that the efflux of this dye was inhibited. Then, it may be concluded that β-lap affects the functioning of Pdr5p transporter, which explains the results obtained on the checkerboard assay. The inhibition of Pdr5p by β-lap allows fluconazole to reach the intracellular concentration needed to perform its antifungal activity. Consequently, a synergic activity between β-lap and fluconazole was achieved.

In order to evaluate whether the inhibition of Pdr5p is related to a decrease in its ATPase activity, purified plasma membranes with a high concentration of Pdr5p were used. Results show that β-lap significantly impaired Pdr5p ATPase activity through a mixed inhibition. In previous studies, our group reported the inhibition of Pdr5p ATPase activity by several distinct substances, such as organic compounds containing tellurium [19]. Nonetheless, the inhibition of ATPase activity is not required for the impairment of efflux pump activity. Farnesol, a natural sesquiterpene compound, inhibits efflux promoted by Candida albicans CaCdr1p without affecting ATPase activity [40]. Interestingly, Loo and Clarke [41] showed that tariquidar, a quinoline compound known as a potent inhibitor of P-glycoprotein, stimulates the ATPase activity of this efflux transporter by changing the nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) conformation.

In addition to a direct action on Pdr5p ATPase activity, β-lap could decrease ATP production by perturbing mitochondrial function. In order to evaluate if the compound is capable of change, the mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), the potentiometric probe JC-1 was used. JC-1 accumulation in mitochondria depends on its potential. Mitochondrial polarization promotes the generation of red J-aggregates, capable of emitting fluorescence at 590 nm. On the other hand, green monomers that possess an emission fluorescence at 530 nm are formed when mitochondria is depolarized. Then, the ratio between the fluorescence intensity at 590 nm/530 nm is directly related to MMP [42]. It was observed that β-lap decreased MMP, indicating an indirect impairment of ATPase activity of Pdr5p, since mitochondrial polarization is essential to ATP production. Previous studies have shown that mitochondria is an important target of β-lap both in fungi [36] and other organisms such as Trypanosoma cruzi [43] and cancer cells [44].

As well as inhibiting the transporter activity, a substance may preclude the efflux process by downregulating the transcription of PDR5 gene. Data obtained showed that β-lap, fluconazole, and the combination β-lap + fluconazole did not change mRNA levels. The inhibition of a fungal MDR transporter by a natural product without alteration in transcript levels has already been reported. Geraniol, a monoterpene found in essential oils of several plants, competitively inhibits CaCdr1p (a C. albicans ABC transporter) through binding to its active site. However, geraniol affects neither the transcription nor the translation of the transporter [6]. Then, we may conclude that the capability of inhibiting ABC transporters gene transcription is not essential for a substance to be used as an efflux pump inhibitor.

Lack of toxicity is an essential requirement for a substance be considered suitable for clinical usage. Thus, the ability of β-lap to disrupt erythrocytes was assessed, by measuring the release of hemoglobin after treatment with the compound. Results show that β-lap did not possess hemolytic activity, and it is fundamental considering a clinical situation where an intravenous administration is mandatory. Furthermore, the majority of drugs taken orally reach the bloodstream to be distributed to the target tissue. Then, using drugs with hemolytic activity would also be harmful considering oral administration.

Besides antifungal activity, β-lap showed synergistic activity with fluconazole against the growth of the S. cerevisiae strain used in this study. Moreover, data obtained indicates that this synergism is related to ROS production, inhibition of Pdr5p ATPase activity, and mitochondrial disfunction, leading to the impairment of efflux mediated by this transporter. In addition, β-lap did not exert toxic effects upon human erythrocytes. Considering our results and the homology between S. cerevisiae Pdr5p and pathogenic fungi MDR transporters, we may suggest that β-lap is a potential candidate to be used in association to fluconazole in the treatment of fluconazole-resistant fungal infections. Further studies employing pathogenic fungi clinical isolates that overexpress these proteins will be conducted to evaluate the effect of β-lapachone on pathogenic fungi.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) (Brazil) and Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ). The authors would like to thank Geralda Rodrigues Almeida for the technical support.

Funding information

This study was financed by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brazil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dudoignon E, Alanio A, Anstey J, Coutrot M, Fratani A, Jully M, et al. Outcome and potentially modifiable risk factors for candidemia in critically ill burns patients: a matched cohort study. Mycoses. 2019;62:237–246. doi: 10.1111/myc.12872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Ami R. Treatment of invasive candidiasis: a narrative review. J Fungi. 2018;4:97. doi: 10.3390/jof4030097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Healey KR, Perlin DS. Fungal resistance to Echinocandins and the MDR phenomenon in Candida glabrata. J Fungi. 2018;4:105. doi: 10.3390/jof4030105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B. Antifungal drug resistance among Candida species: mechanisms and clinical impact. Mycoses. 2015;58:2–13. doi: 10.1111/myc.12330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardno TS, Ivnitski-steele I, Lackovic K, Cannon RD. Targeting efflux pumps to overcome antifungal drug resistance. Future Med Chem. 2016;8:1485–1501. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2016-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh S, Fatima Z, Ahmad K, Hameed S. Fungicidal action of geraniol against Candida albicans is potentiated by abrogated CaCdr1p drug efflux and fluconazole synergism. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0203079. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavalheiro M, Pais P, Galocha M. Host-pathogen interactions mediated by MDR transporters in fungi: as pleiotropic as it gets! Genes. 2018;9:332. doi: 10.3390/genes9070332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golin J, Ambudkar SV. The multidrug transporter Pdr5 on the 25th anniversary of its discovery: an important model for the study of asymmetric ABC transporters. Biochem J. 2015;467:353–363. doi: 10.1042/BJ20150042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad R, Wergifosse PD. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel gene of Candida albicans, CDR1, conferring multiple resistance to drugs and antifungals. Curr Genet. 1995;27:320–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00352101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanglard D, Ischer F, Monod M, Billel J (1997) Cloning of Candida albicans genes conferring resistance to azole antifungal agents: characterization of CDR2, a new multidrug ABC transporter gene. Microbiology:405–416 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Demuyser L, Van Dijck P. Can Saccharomyces cerevisiae keep up as a model system in fungal azole susceptibility research ? Drug Resist Updat. 2019;42:22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliveira D, Sousa E, Alves S, Tomaz V, Suarez S, Lima M, et al. Effects of a novel b-lapachone derivative on Trypanosoma cruzi : parasite death involving apoptosis, autophagy and necrosis. Int J Parasitol Drugs Resist. 2016;6:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Y, Zhou X, Xu M, Piao J, Zhang Y, Lin Z. β-Lapachone suppresses tumour progression by inhibiting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in NQO1-positive breast cancers. Sci Rep. 2017;7:2681. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02937-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moraes DC, Curvelo JAR, Anjos CA, Moura KCG, Pinto MCFR, Portela MB. β-Lapachone and α-nor-lapachone modulate Candida albicans viability and virulence factors. J Mycol Med. 2018;28:314–319. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Decottignies A, Kolaczkowski M, Balzi E, Goffeau A. Solubilization and characterization of the overexpressed PDR5 multidrug resistance nucleotide triphosphatase of yeast. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12797–12803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hooker SC. The constitution of lapachol and its derivatives. Part IV. Oxidation with potassium permanganate. J Am Chem Soc. 1936;58:1168–1173. doi: 10.1021/ja01298a029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rex JH, Alexander BD, Andes D, Arthington-Skaggs B, Brown SD, Chaturvedi V et al (2008) Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts: approved standard-third edition. Clin Lab Stand Inst:1–25

- 18.Niimi K, Harding DRK, Parshot R, King A, Lun DJ, Decottignies A, Niimi M, Lin S, Cannon RD, Goffeau A, Monk BC. Chemosensitization of fluconazole resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and pathogenic fungi by a D-octapeptide derivative. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1256–1271. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1256-1271.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Figueira L, De Sá R, Toledo FT, De Sousa BA, Gonçalves AC, Tessis AC et al (2014) Synthetic organotelluride compounds induce the reversal of Pdr5p mediated fluconazole resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Microbiol:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Bueno I, Batista J, Rocha T, Silva M. Diphenyl diselenide ( PhSe )2 inhibits biofilm formation by Candida albicans, increasing both ROS production and membrane permeability. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2015;29:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keniya MV, Fleischer E, Klinger A, Cannon RD. Inhibitors of the Candida albicans major facilitator superfamily transporter Mdr1p responsible for fluconazole resistance. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rangel LP, Fritzen M, Yunes RA, Leal PC, Creczynski-Pasa TB, Ferreira-Pereira A. Inhibitory effects of gallic acid derivatives on Saccharomyces cerevisiae multidrug resistance protein Pdr5p. FEMS Yeast Res. 2010;10:244–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2009.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dulley JR. Determination of inorganic phosphate in the presence of detergents or protein. Anal Biochem. 1975;67:91–96. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90275-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiske CH, Subbarow Y. The colorimetric determination of phosphorus. J Biol Chem. 1925;66-375:400. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang JH, Choi H, Kim AR, Yun JW, Yu R, Woo ER, Lee DG. Hibicuslide C-induced cell death in Candida albicans involves apoptosis mechanism. J Appl Microbiol. 2014;117:1400–1411. doi: 10.1111/jam.12633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ricardo E, Costa-de-oliveira S, Dias AS. Ibuprofen reverts antifungal resistance on Candida albicans showing overexpression of CDR genes. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009;9:618–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2009.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valach M (2016) RNA extraction using the “home-made” TRIzol substitute. protocols.io. http://www.protocols.io/view/RNA-extraction-using-the-home-made-Trizol-substitu-eiebcbe. Accessed 10 July 2019

- 28.De Oliveira HC, Monteiro MC, Rossi AS. Identification of off-patent compounds that present antifungal activity against the emerging fungal pathogen Candida auris. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019;9:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C, Zhang Y, Zhang W, Yuan S, Ng T, Ye X. Purification of an antifungal peptide from seeds of Brassica oleracea var gongylodes and investigation of its antifungal activity and mechanism of action. Molecules. 2019;24:1337. doi: 10.3390/molecules24071337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spitzer M, Robbins N, Wright GD. Combinatorial strategies for combating invasive fungal infections. Virulence. 2017;8:169–185. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1196300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prasad R, Rawal MK. Efflux pump proteins in antifungal resistance. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menacho-Márquez M, Murguia JR. β-Lapachone activates a Mre11p-Tel1p G1/S checkpoint in budding yeast. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2509–2516. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.21.3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silva JL, Mesquita ARC, Ximenes EA. In vitro synergic effect of β -lapachone and isoniazid on the growth of Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:580–582. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762009000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macedo L, Fernandes T, Silveira L, Mesquita A, Franchitti AA, Ximenes EA. β-Lapachone activity in synergy with conventional antimicrobials against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Phytomedicine. 2013;21:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramos-Pérez C, Lorenzo-Castrillejo I, Quevedo O, García-Luis J, Matos-Perdomo E, Medina-Coello C, Estévez-Braun A, Machín F. Yeast cytotoxic sensitivity to the antitumour agent β-lapachone depends mainly on oxidative stress and is largely independent of microtubule or topoisomerase-mediated DNA damage. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;92:206–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anaissi-Afonso L, Oramas-Royo S, Ayra-Plasencia J, Martín-Rodríguez P, García-Luis J, Lorenzo-Castrillejo I, et al. Lawsone, juglone, and β-lapachone derivatives with enhanced mitochondrial-based toxicity. ACS Chem Biol. 2018;13:1950–1957. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.8b00306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menacho-Márquez M, Rodríguez-Hernández CJ, Villarong MÁ, Pérez-Valle J, Gadea J, Belandia B, et al. EIF2 kinases mediate β-lapachone toxicity in yeast and human cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:630–640. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.994904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li DD, Chai D, Huang XW, Guan SX, Du J, Zhang HY, et al. Potent in vitro synergism of fluconazole and osthole against fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e00436–e00417. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00436-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ivnitski-steele I, Holmes AR, Lamping E, Monk BC, Richard D, Sklar LA. Identification of Nile red as a fluorescent substrate of the Candida albicans ABC transporters Cdr1p and Cdr2p and the MFS transporter Mdr1p. Anal Biochem. 2009;394:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma M, Prasad R. The quorum-sensing molecule farnesol is a modulator of drug efflux mediated by ABC multidrug transporters and synergizes with drugs in Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4834–4843. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00344-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loo TW, Clarke DM. Tariquidar inhibits P-glycoprotein drug efflux but activates ATPase activity by blocking transition to an open conformation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;92:558–566. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chazotte B. Labeling mitochondria with JC-1. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;6:1103–1104. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot065490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Menna-Barreto RFS, Corrêa JR, Pinto AV, Soares MJ, De Castro SL. Mitochondrial disruption and DNA fragmentation in Trypanosoma cruzi induced by naphthoimidazoles synthesized from β-lapachone. Parasitol Res. 2007;101:895–905. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0556-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li YZ, Li CJ, Pinto AV, Pardee AB. Release of mitochondrial cytochrome C in both apoptosis and necrosis induced by β-lapachone in human carcinoma cells. Mol Med. 1999;5:232–239. doi: 10.1007/BF03402120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]