Abstract

Purpose

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and its enzymatic product prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) possess tumor-promoting activity, and COX-2 is considered as a candidate for targeted cancer therapy. However, several randomized clinical trials using COX-2 inhibitors to treat advanced lung cancer have failed to improve survival indices. To employ a more effective therapeutic strategy to inhibit the COX-2-PGE2 axis in tumors, it is necessary to revisit the mechanism underlying the protumor effect of COX-2-PGE2.

Patients and Methods

Immunohistochemistry was used to predict the expression and prognostic value of COX-2 in lung adenocarcinoma samples. The mRNAs or proteins expression of COX-2, pAKT1/2/3, pErk1/2 and pCREB were detected after different treatments by qPCR or Western blot. The impacts of PGE2 and some inhibitors on cell proliferation and migration ability were verified by CCK-8 and transwell assays, respectively.

Results

In this study, we first confirmed that COX-2 expression in tumor specimens is associated with the pathological stage of the disease. Next, using lung adenocarcinoma cell lines, we found that exogenous PGE2 induces the expression of COX-2 at the mRNA and protein levels. Moreover, downregulation of COX-2 expression restrained PGE2-induced cancer cell proliferation and migration. Mechanistic analysis revealed that PGE2 stimulation activates the PKA-CREB and PI3K-AKT pathways. Downregulation of CREB expression abrogated PGE2-induced COX-2 expression. Moreover, inhibition of PI3K-AKT signaling suppressed the activation of CREB and PGE2-induced COX-2 expression. Specific inhibitors for PI3K and AKT suppressed COX-2 mRNA expression in ex vivo cultures of tumor specimens with PGE2.

Conclusion

Simultaneous targeting of COX-2 and PI3K-AKT effectively suppressed PGE2-induced cell proliferation and migration and both acted in a synergistic manner. Targeting the COX-2-PGE2 positive feedback loop may be therapeutically beneficial to lung adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: PGE2, COX-2, AKT, EP receptor, lung adenocarcinoma

Introduction

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) overexpression is frequently seen in lung adenocarcinoma.1,2 Its major enzymatic product, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), plays a key role in promoting tumor growth and suppressing tumor immunity,3,4 and thus COX-2 is considered as a candidate for targeted cancer therapy. However, a meta-analysis of nine randomized clinical trials of COX-2 inhibitors in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) concluded that COX-2 inhibitors have no impact on survival indices.5 Additionally, there is concern regarding the cardiovascular and hematologic toxicities of COX-2 inhibitors.5 The unsuccessful use of COX-2 inhibitors in the clinical setting for the treatment of lung cancer suggests that it is necessary to revisit the mechanisms underlying the protumor effect of the COX-2-PGE2 axis.

The biological functions governed by PGE2 are mediated by signaling through distinct E-type prostanoid (EP) receptors that consist of four subtypes, namely, EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4.6 PGE2 via EP3 activates Src-STAT3 signaling and promotes the progression of lung adenocarcinoma.7 PGE2 also increases cell migration and invasiveness in an EP4-dependent manner.8–10 Recently, several studies have demonstrated that PGE2 induces COX-2 expression thereby forming a positive feedback loop. PGE2 induces COX-2 expression in podocytes through a PKA-independent mechanism,11 and PGE2 induces COX-2 expression in LoVo colon cancer cells.12 Kim and coworkers have demonstrated that PGE2 signaling activates YAP1 and leads to the upregulation of COX-2 expression in a PI3K-AKT-independent manner. Furthermore, this positive feedback loop is responsible for PGE2-mediated colon regeneration and carcinogenesis following colitis.13 Therefore, targeting the COX-2-PGE2 positive feedback loop may be a novel therapeutic approach for lung cancer.

In this study, we demonstrate that PGE2 induces COX-2 expression in lung cancer cells. We reveal that PGE2 stimulation activates CREB, and CREB is required for PGE2-induced COX-2 expression. Moreover, PGE2 stimulation leads to activation of the PI3K-AKT pathway, and interestingly, inhibition of PI3K-AKT results in suppression of PGE2-mediated phosphorylation of CREB and COX-2 expression. Blocking the COX-2-PGE2 positive feedback loop using a PI3K inhibitor abrogates the PGE2-induced protumor effect. The PI3K inhibitor acts synergistically with a COX-2 inhibitor to reduce lung cancer cell proliferation and migration.

Materials and Methods

Human Subjects and Tissue Samples

Human lung adenocarcinoma specimens were obtained from 109 patients who underwent pulmonary resection prior to radiation or chemotherapy between 2012 and 2016 at the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Tongji Hospital (Wuhan, China). Histological diagnosis was based on the World Health Organization criteria for lung cancer. Disease stage was based on the 7th edition of 2010 AJCC TNM staging guidelines. All patients signed informed consent and the use of human tissue samples was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Tissue Microarray (TMA) and Immunohistochemistry Analysis

TMA was prepared from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens. Representative areas of the tumors were identified by H&E staining, and 1.5 mm tissue cores were obtained in duplicate and embedded in a TMA. Sections cut from the TMA were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated across an ethanol gradient. Sections were pretreated with heat-induced epitope retrieval by microwave heating (400 W) for 15 min in EDTA retrieval buffer (pH 9). Buffer was preheated to 100°C and followed by endogenous peroxidase blocking for 10 min with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide. The sections then were washed and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin for 30 min. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with the primary anti-COX-2 antibody (1:400), anti-EP1 antibody (1:400), anti-EP2 antibody (1:800), anti-EP3 antibody (1:200), or anti-EP4 antibody (1:400) at 4°C overnight. A negative control was performed using identical methods except for the primary antibody.

For COX-2 and EP receptor evaluation, the intensity of COX-2 and EP receptor immunoreactivity was graded as 0 = negative, 1 = weak, 2 = moderate, and 3 = strong staining. The tissue cores showed a degree of staining across nearly all (>75%) of the tumor cells. The scores were defined as low (< 2) or high (≥ 2) immunoreactivity. Two independent observers examined the stained sections in a blinded fashion.

Cell Lines and Cell Culture Related Reagents

Human lung adenocarcinoma A549, H1975, and HCC827 cells were obtained from Cobioer Biosciences (Nanjing, China). Authentication of these cell lines was performed by short tandem repeat (STR) DNA profiling by Cobioer Biosciences in July 2017. All of the cell lines were passaged for fewer than four months. The cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Hyclone, Logan UT, USA). Lung cancer cells were treated with PGE2 (MedChem Expression, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) or Sulprostone, Butaprost and CAY10598 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), which are selective agonists for EP1/EP3, EP2, and EP4, respectively. The inhibitors celecoxib (COX-2), GDC-0068 (AKT) and LY294002 (PI3K) were obtained from MedChem Express. All of the EP agonists and inhibitors were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The final concentration of DMSO in cell culture did not exceed 0.1% (v/v). The cells in the experiments that were treated with DMSO alone served as the vehicle control (blank).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

The TRIzol-based method (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used to isolate total RNA. RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the RT reagent kit (TAKARA, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Vilnius, Lithuania). The primers were obtained from TsingKe Biological Technology (Wuhan, China), and the sequences of the primers presented in Supplementary Table 1. Negative controls without template were also included in the experiments, and all of the reactions were conducted in triplicate. β-actin was used as internal control. Relative expression of the target genes was determined by the ΔΔCT method.

Western Blot Analysis

Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. The blots were developed using the ECL detection system. All of the antibodies used are shown in Supplementary Table 2. To ensure that equal amounts of sample protein were used in electrophoresis and immunoblotting, β-actin was employed as the protein loading control.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

PGE2 levels were detected in culture medium using solid phase sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assays according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Bio-Swamp Life Science, Shanghai, China). The PGE2 assay sensitivity was 6 pg/mL, and the assay range was 30~2400 pg/mL.

Transfections

Short interfering RNA (siRNA) sequences specifically targeting human COX-2 and CREB were synthesized by RiboBio (Guangzhou, China). Reverse transfection was used to deliver siRNA into cells. Briefly, siRNA (50 nM) and Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) were gently premixed in medium without serum as per manufacturer’s recommendations. After adding the transfection mixture to the culture plate, cell suspensions were seeded into the culture plate and maintained in 10% FBS for 24 h or 48 h. The efficacy of knockdown target gene expression was subjected to RT-PCR and Western blot analysis.

Cell Proliferation Assay

Cell proliferation was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8 kit, Dojindo Molecular Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan). Cell suspensions were seeded (3000~5000/100 μL/well) and cultured overnight before exposure to the indicated stimuli. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer (TECAN).

Transwell Migration Assay

Cell migration assay was conducted using 8 μm-pore size Transwell chambers (Corning, NY, USA). Briefly, cells were suspended in serum-free medium and plated into the upper chambers (7×104/100 μL/well). In the lower chambers, medium supplemented with 10% FBS was used as a chemoattractant. PGE2 and other indicated reagents were added to both chambers at a constant concentration. After 24 h of incubation, the cells that migrated through the membrane to the bottom surface were immediately fixed with 4% (w/v) para-formaldehyde, and subsequently stained with 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet. The migratory cells were examined under an optical microscope at 200× magnification. The average number of migratory cells was obtained from three randomly selected fields.

Ex vivo Culture of Patient-Derived Lung Cancer Explants

Ex vivo cultures were performed as previously described.14 Fresh lung cancer tissues were dissected and placed on a gelatin sponge bathed in RPMI-1640 media that was supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 units/mL penicillin-streptomycin. In addition, 0.01% DMSO, PGE2, celecoxib, LY294002 or GDC-0068 was added to the media as indicated. Tissues were cultured at 37°C for 12 h, then snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA extraction.

Statistical Analysis

Data in the bar graphs are displayed as means ±SD. The comparison of differences in the bar graph was performed using a two-tailed t-test or the Mann Whitney U-test (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001). The association of clinic pathological characteristics and COX-2 expression was analyzed using the χ2 test or the Mann Whitney U-test as appropriate. The χ2 test analysis was performed with SPSS, and other statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software v7.0. Disease-free survival (DFS) rates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, with follow-up starting at the time of surgery.

Results

Elevated COX-2 Expression Indicates an Unfavorable Prognosis in Patients with Locally Advanced Lung Adenocarcinoma

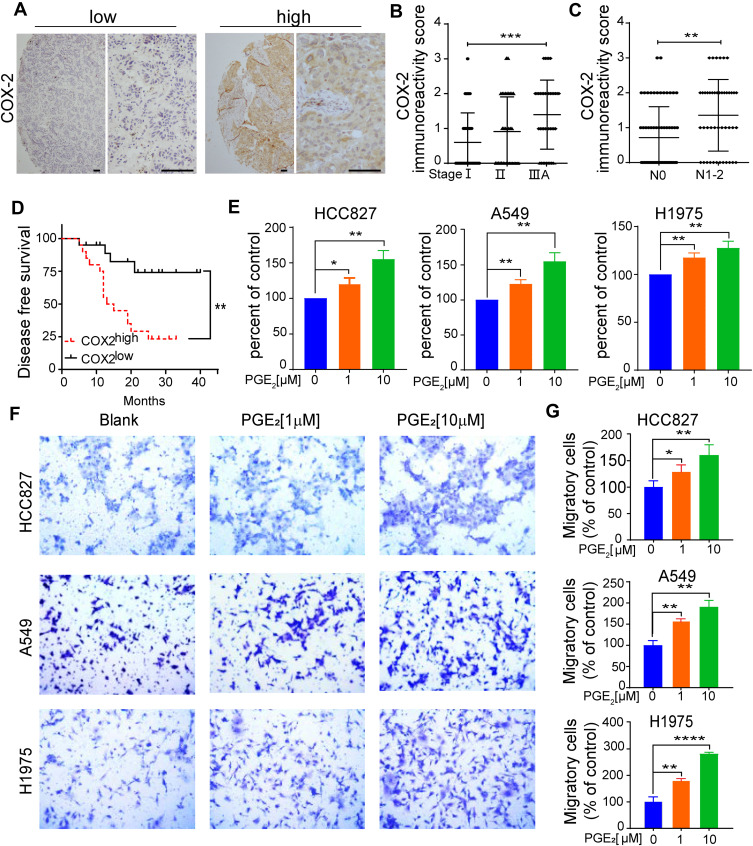

COX-2 overexpression is considered to be a negative predictive factor for the survival of patients with stage I NSCLC.1,2 We first examined whether COX-2 expression is associated with the progression of lung adenocarcinoma. COX-2 expression was evaluated in 109 tumor specimens of patients with lung adenocarcinoma from our clinical archives. The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients are presented in Supplementary Table 3. Out of a total 109 samples, 37 cases (34%) exhibited markedly intense COX-2 immunoreactivities in epithelial compartments, whereas the remaining 72 cases (66%) showed weak or undetectable immunostaining of COX-2 (Figure 1A). COX-2 expression significantly increased in tumors from patients with locally advanced lung adenocarcinoma (stage IIIA) compared to tumors from stage I disease (Figure 1B). A significant association between elevated COX-2 expression and nodal involvement was observed as well (Figure 1C). There was no significant association between elevated COX-2 expression and various clinicopathological features, including age, sex, smoking history, or EGFR mutation status (Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 1.

Elevated COX-2 expression is associated with the progression of lung adenocarcinoma and indicates poor prognosis in patients with locally advanced lung adenocarcinoma. (A) Detection of COX-2 expression in tumor tissues by immunohistochemistry. Representative immunostaining of COX-2 in tumor tissue array, scale bar=100µM. (B) COX-2 expression in tumor tissues from patients with lung adenocarcinoma at TNM stage I (n = 35), stage II (n = 34) and stage IIIA (n = 40). Data are presented as mean± SD. ***p < 0.001 (Mann–Whitney U-test analysis, P = 0.0004). (C) The association of COX-2 expression and lymph node metastasis status. N0 indicates no metastasis in examined lymph nodes. Data are presented as mean± SD. **p < 0.01 (Mann–Whitney U-test analysis, P = 0.0011). (D) Kaplan-Meier curves of DFS for 40 patients with IIIA lung adenocarcinoma according to the levels of COX-2 expression. The COX-2 IHC staining score was used to classify patients into two groups, scores ≥ 2 were classified into the COX-2high group, whereas the rest were referred to as the COX-2low group. Low COX-2 expression significantly prolonged DFS, **p < 0.01 (P = 0.0031). (E) The effect of PGE2 on cell proliferation was evaluated by CCK-8 assay. The cells (3~5x103cells/well) were stimulated with the indicated concentration of PGE2 for 72 h. Cell proliferation was assessed by CCK-8 kit. PGE2 untreated cells were used as control. The Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (two-sided Student’s t-test). (F, G) The effect of PGE2 on cell migration was assessed using transwell chambers. The cells (7×104 cells/100 µL RPMI-1640) were suspended in serum-free medium with or without PGE2. After 24 h of cell culture, the number of cells on the underside of the transwell inserts were counted in three random fields under a light microscope (magnification, 200x). Blank indicates the cells without PGE2 treatment. The Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (two-sided Student’s t-test).

We next investigated whether COX-2 had prognostic value in locally advanced lung adenocarcinoma. A total of 40 patients with stage IIIA lung adenocarcinoma were enrolled in this study, and the subjects were divided into a COX-2high group (defined as an immunoreactivity score of ≥ 2, n = 20) and a COX-2low group (the remaining patients, n = 20). Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrated that at a median follow-up time of 19 months, the median DFS for patients with COX-2low was 20 months (95% CI, 12.17–29.83 months), whereas that for the COX-2high group was 14 months (95% CI, 6.43–19.58 months). Low COX-2 expression significantly prolonged DFS time (Figure 1D). Our findings strongly suggest that elevated COX-2 expression in tumors is related to an unfavorable prognosis for patients with locally advanced lung adenocarcinoma.

COX-2 overexpression is associated with increased production of PGE2, which promotes cell proliferation and migration in many types of cancers, including colon, breast, and lung.15 We found that additional PGE2 in the cell cultures significantly promoted the proliferation (Figure 1E) and migration in all three tested lung adenocarcinoma cell lines and in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1F and G).

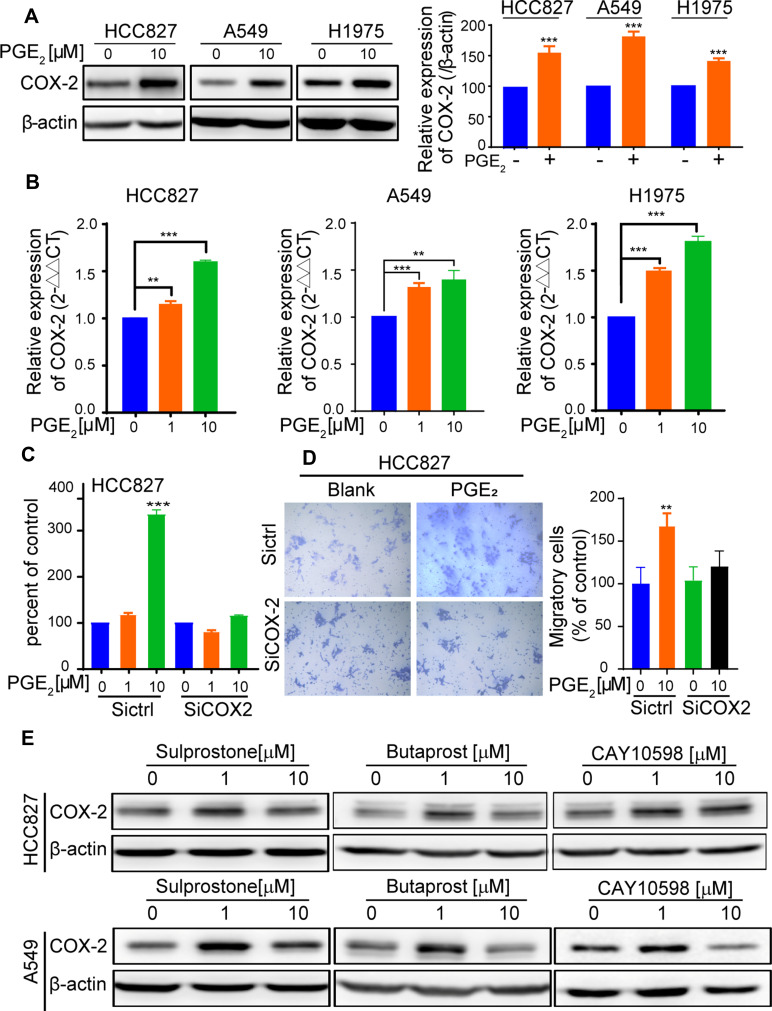

PGE2 Upregulates COX-2 Expression in Lung Cancer Cells

PGE2 signaling has been reported to increase COX-2 expression in colonic tissues and to form a positive feedback loop that is responsible for PGE2-mediated colon regeneration and carcinogenesis following colitis.13 In this study, cell cultures supplemented with PGE2 led to a significant increase in COX-2 protein expression (Figure 2A). We also observed that PGE2 induced COX-2 mRNA expression in the HCC827, A549, and H1975 cells (Figure 2B). We show for the first time that PGE2 induces COX-2 expression in lung adenocarcinoma cells.

Figure 2.

PGE2 upregulates COX-2 expression and downregulation of COX-2 expression abrogates PGE2-mediated protumor effects. (A) The cells were cultured with or without PGE2 for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were harvested and lysed. COX-2 expression was analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-COX-2 antibody. The bar graphs show densitometric analysis of changes in the abundance of COX-2 as normalized to β-actin. (B) The cells were treated with the indicated concentration of PGE2 for 6 h. The expression of COX-2 was detected by RT- PCR. The Data are presented as the mean ±SD (n = 3, two-sided Student’s t-test, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (C) HCC827 cells were transfected with siRNA-control or siRNA-COX-2 for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were treated with PGE2 for 72 h. Proliferation was assessed using a CCK8 kit. Knockdown of COX-2 completely abrogates PGE2-induced cell proliferation (***p < 0.001). (D) HCC827 cells were transfected with siRNA-COX-2 or siRNA-control for 48 h. Subsequently, the cells were suspended in serum-free medium with or without PGE2. After 24 h of cell culture, cells on the underside of the transwell inserts were counted in three random fields under a light microscope (magnification, 200x). Data are presented as the mean ± SD (**p < 0.01, ns, not significant.). (E) The cells were treated with EP agonists, including Sulprostone for EP1/EP3, Butaprost for EP2, and CAY10598 for EP4. COX-2 expression was detected by immunoblotting after 24 h of culture.

To determine whether PGE2-induced COX-2 expression is responsible for the pro-tumor effect of PGE2, COX-2 expression was downregulated by RNA interference (Figure S1A). Downregulation of COX-2 significantly reduced PGE2 production by A549 and HCC827 cells (Figure S1B). Moreover, PGE2-mediated cell proliferation as well as migration was abrogated in COX-2 knockdown cells (Figure 2C and D). Our findings suggest that PGE2 and COX-2 form a positive regulatory loop that is crucial for PGE2-mediated protumor effects.

To determine the role of EP receptors in inducing COX-2 expression by PGE2, we examined the EP receptor expression in A549, HCC827, and H1975 cells (Figure S1C). All three cell lines expressed EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4 to different degrees. Next, we assessed whether the selective EP subtype ligand agonists Sulprostone, Butaprost and CAY10598 for EP1/EP3, EP2 and EP4, respectively, induce COX-2 expression. Stimulation of HCC827 and A549 cells with the indicated agonists led to a marked increase in COX-2 expression as determined by Western blot analysis (Figure 2E). The results indicate that PGE2-induced COX-2 expression in lung cancer cells could be mediated through any functional EP receptors. Interestingly, we also observed that in 109 tumor specimens, COX-2 immunoreactivity was significantly correlated with the expression levels of the EP receptors (EP high was defined as having an immunoreactivity score of ≥ 2) (Figure S1D and Supplementary Table 4).

Activation of PI3K-AKT and CREB is Required for PGE2-Induced COX-2 Expression

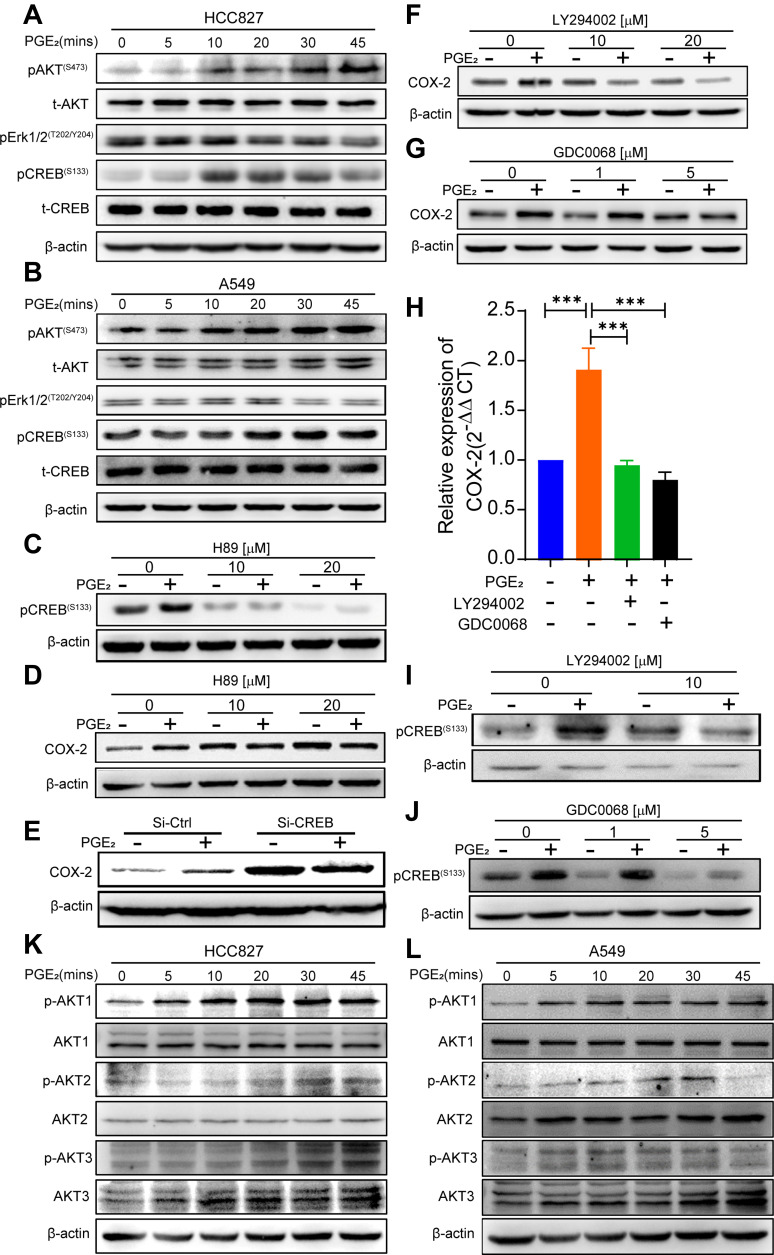

To further elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying PGE2-induced COX-2 expression, we examined the activation status of the PKA-CREB, PI3K-AKT and MEK-ERK1/2 pathways in A549 and HCC827 cells in response to PGE2 stimulation. The addition of PGE2 to the cell cultures led to a robust phosphorylation of CREB 10 min after exposure and decreased by 45 min. PGE2-induced phosphorylation of AKT at serine 473 (S473) was apparent after 20 min and lasted for at least 45 min (Figure 3A and B). In contrast, phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was slightly reduced in HCC827 cells after exposure to PGE2.

Figure 3.

PGE2-induced activation of the PI3K-AKT and CREB pathway is required for COX-2 induction. (A, B) HCC827 cells and A549 cells were stimulated with 10 µM PGE2 at the indicated time points. The activation of downstream signals of PGE2 was analyzed by immunoblotting. (C, D) HCC827 cells were pretreated with PKA inhibitor H89 for 30 min and then treated with PGE2 for an additional 30 min or 24 h. Phosphorylation of CREB (30 min) and COX-2 expression (24 h) were evaluated by Western blotting. H89 inhibits phosphorylation of CREB and PGE2-induced COX-2 expression. (E) HCC827 cells were transfected with siRNA-control or siRNA-CREB for 48 h, and the cells were treated with or without PGE2 for 24 h. COX-2 expression was evaluated by immunoblotting. Knockdown of CREB abrogates PGE2-mediated upregulation of COX-2 expression. (F, G) HCC827 cells were pretreated with either PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or AKT inhibitor GDC0068 for 30 min and then treated with PGE2 for an additional 24 h. COX-2 expression was evaluated by immunoblotting. Inhibition of PI3K-AKT reduces PGE2-mediated COX-2 expression. (H) ex vivo human lung adenocarcinoma specimens were cultured with PGE2 and PI3K-AKT inhibitors COX-2 mRNA expression was assessed by qPCR (***P < 0.001). The data represent tumor specimens from four individual lung cancer patients. (I, J) HCC827 cells were pretreated with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or AKT inhibitor GDC0068 for 30 min and then treated with PGE2 for an additional 30min. CREB phosphorylation was evaluated by immunoblotting. PGE2-induced phosphorylation of CREB is diminished by inhibition of PI3K-AKT. (K, L) HCC827 cells and A549 cells were cultured with PGE2 for the indicated time intervals. Phosphorylation of ATK 1, AKT2, and AKT3 was detected by Western blotting using specific antibodies against each of the AKT isoforms. AKT1 is activated in both cell lines in response to PGE2 stimulation.

We next determined which signaling pathway(s) are responsible for PGE2-induced COX-2 expression. PKA is the key main regulator of p-CREB. Pretreatment of HCC827 cells with the PKA inhibitor H89 suppressed PGE2-induced phosphorylation of CREB (Figure 3C). Consequently, cell cultures supplemented with H89 blocked PGE2-induced COX-2 expression (Figure 3D). CREB is a transcription factor that regulates a wide variety of genes by binding to cyclic AMT response element (CRE) in promoter regions, including COX-2.16,17 To determine whether CREB is required for PGE2-induced COX-2 expression, we downregulated CREB expression by RNA interference (Figure S2A) and subsequently assayed COX-2 expression upon PGE2 stimulation. Downregulation of CREB expression resulted in diminished PGE2-induced COX-2 expression (Figure 3E), suggesting that CREB is required for PGE2-induced COX-2 expression. The activation of AKT by PGE2 in colonic epithelial cells is not responsible for PGE2-induced COX-2 expression.13 We sought to determine whether this is also the case in lung cancer cells. HCC827 cells were treated with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 in addition to PGE2. PGE2-induced phosphorylation of AKT was abrogated by LY294002 at a concentration of 10 µM (Figure S2B). PGE2-induced COX-2 expression was suppressed by LY294002 (Figure 3F). To determine whether AKT activation is required for COX-2 expression, we used the pan-AKT-specific inhibitor GDC-0068.18 The AKT inhibitor suppressed PGE2-induced COX-2 expression in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3G). These in vitro findings were confirmed by ex vivo culture of tumor specimens with PGE2 (Figure 3H).

Activation of PI3K-AKT signaling is capable of phosphorylating numerous downstream signaling proteins. Several studies have shown that the activation of AKT is capable of phosphorylating CREB on Ser 133 and increasing its transcriptional activation.19 However, whether PGE2-induced activation of PI3K-AKT signaling affects phosphorylation of CREB remains unknown. Inhibition of PI3K-AKT activation by either LY294002 (Figure 3I) or GDC-0068 (Figure 3J) significantly diminished PGE2-induced phosphorylation of CREB. The mammalian serine/threonine AKT kinases comprise three isoforms, namely, AKT1, AKT2, and AKT3. To further determine which AKT isoform(s) are affected by PGE2, specific antibodies against each isoform were used. AKT1 was clearly activated by PGE2 stimulation in HCC827 (Figure 3K) and A549 cells (Figure 3L). Thus, our study for the first time demonstrates that activation of CREB via both PKA and PI3K-AKT pathways is required for PGE2-induced COX-2 expression in lung cancer cells.

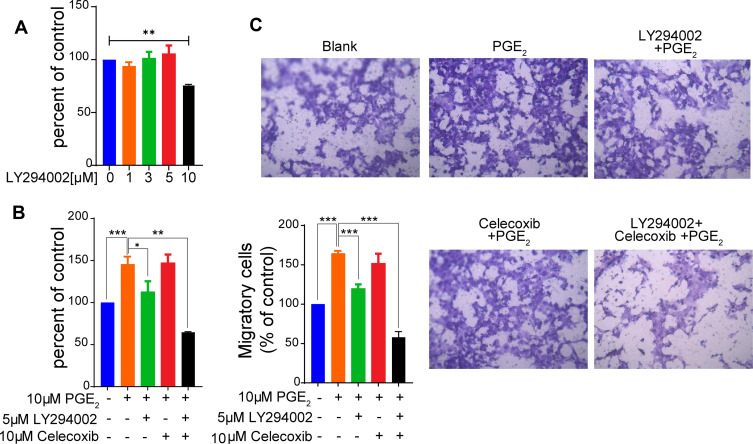

Inhibition of PI3K-AKT Signaling Antagonizes PGE2-Induced Protumor Effects

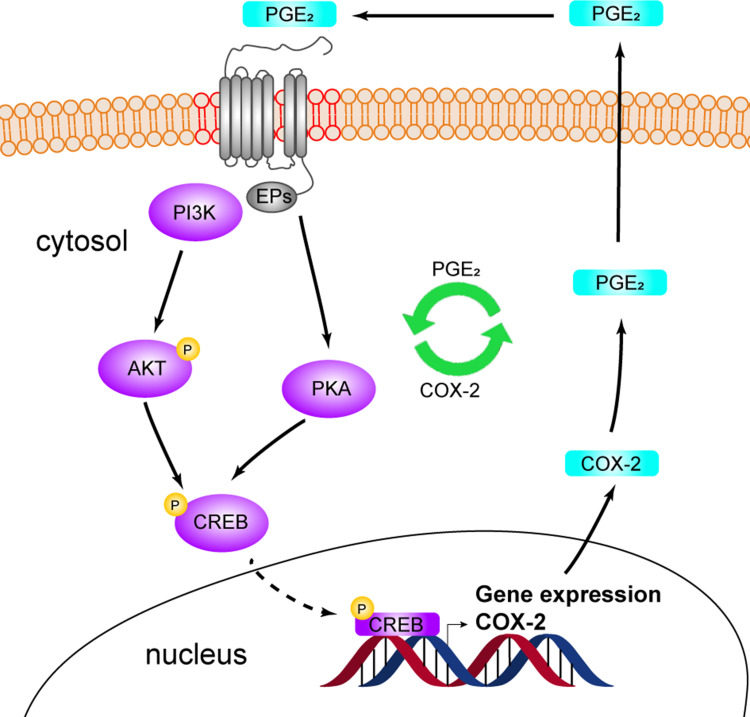

To determine whether inhibition of PI3K-AKT signaling inhibits PGE2-mediated protumor effects, we first examined the effect of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 on cell proliferation without the addition of PGE2. The addition of LY294002 at a concentration of 5 µM in HCC827 cell cultures had almost no inhibitory effect on cell proliferation (Figure 4A). Tumor cells treated with PGE2 showed a significant increase in cell proliferation (Figure 4B). The addition of LY294002 at a concentration of 5 µM almost abrogated PGE2-induced cell proliferation. Moreover, cultures of HCC827 cells with PGE2 in the presence of LY294002 at 5 µM significantly reduced PGE2- induced cell migration (Figure 4C). Celecoxib has been applied in several clinical trials,20,21 but the overall outcome remains debatable.5 The efficacy of celecoxib is at least partially limited by its toxicities. Figure S3 shows that the treatment of tumor cells with celecoxib resulted in a reduction in cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. Celecoxib at a concentration of 10 µM had minimal effects on suppressing cell proliferation. The tumor cells cultured with 10 µM celecoxib did not affect PGE2-induced cell proliferation and migration (Figure 4B and C). Interestingly, the combination of 10 µM of celecoxib and 5 µM of LY294002 resulted in a potent inhibitory effect on cell proliferation and migration. These findings indicate that LY294002 plays a synergistic role with celecoxib in suppressing COX-2-PGE2 axis-mediated protumor effects. Taken together, our results showed that stimulation of lung cancer cells with PGE2 induces COX-2 expression via activation of PKA-CREB and PI3K-AKT pathways (Figure 5). Inhibition of PI3K-AKT blocks the PGE2-induced positive feedback loop, thereby improving the efficacy of celecoxib.

Figure 4.

Celecoxib and LY294002 synergistically inhibit the proliferation and migration of lung cancer cells. (A) HCC827 cells were cultured with the indicated concentrations of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002. Cell proliferation was assessed using a CCK-8 assay. LY294002 at a concentration of 10 µM significantly inhibits cell proliferation (**p < 0.01), whereas < 10 µM of LY294002 has no effect on cell proliferation. (B) HCC827 cells were pretreated with 5µM LY294002 or 10 µM of the COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib, which has no effect on cell proliferation as shown in Figure S3 or the combination of these two inhibitors for 1 h and subsequently cultured with PGE2 for 72 h. The proliferation was evaluated using a CCK-8 kit. The combination of LY294002 and Celecoxib dramatically suppresses cell proliferation. The data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3, Student’s t-test; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). The data represent at least three independent experiments. (C) The effect of LY294002 and Celecoxib on PGE2-mediated cell migration was evaluated using a transwell assay. The combination of LY294002 and Celecoxib significantly reduces migratory capability of tumor cells. The data are presented as the mean ± SD (two-sided Student’s t-test, n = 3, ***P < 0.001). Blank indicates the cells that were not treated with PGE2, LY294002 or Celecoxib.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram showing the formation of the PGE2-COX-2 positive feedback loop. PGE2 induces COX-2 expression through any functional EP receptor. The activation of PI3K-AKT and CREB by PGE2 is required for the upregulation of COX-2 expression. Elevated COX-2 expression is responsible for the PGE2-mediated pro-tumor effects. Targeting both PI3K-AKT and COX-2 effectively abrogates PGE2-mediated increase in cell proliferation and migration.

Discussion

Elevated COX-2 expression in tumors is a marker of poor prognosis in stage I of lung adenocarcinoma.1,2 Here, we found a significant association between elevated COX-2 expression and disease stage. Moreover, a correlation between an increase in COX-2 expression in tumors and an unfavorable DFS in lung adenocarcinoma patients was observed in stage IIIA disease. Our findings confirmed and extended those of previous studies as well as indicated that COX-2 promotes lung adenocarcinoma progression.

The protumor effect of COX-2 in lung adenocarcinoma has been extensively investigated. COX-2 induction and overexpression are associated with an increase in production of PGE2, one of the major products of COX-2 that is known to modulate cell proliferation, cell death, and tumor invasion in many types of cancer.15 Our study confirmed that PGE2 induces an increase in cell proliferation and migration in three lung adenocarcinoma cell lines, namely, A549, HCC827, and H1975, which harbor frequent mutations in KRAS (A549), EGFR (H1975, HCC827), PIK3CA (H1975), and TP53 (H1975, HCC827) to reflect the mutational spectrum detected in patients.

One important finding in our study is that PGE2 can induce lung cancer cells to express COX-2. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first demonstration of the existence of a positive feedback loop between COX-2 and PGE2 in lung cancer. The positive regulatory relationship between COX-2 and PGE2 can reinforce the tumor-promoting effect mediated by the COX-2-PGE2 axis. Indeed, our data show that the downregulated COX-2 expression abrogates PGE2-induced cell proliferation and migration.

Recent findings indicate that PGE2-induced COX-2 expression in colon cancer is mediated by EP2 and EP4 receptors.12,13 However, we demonstrated that besides EP2 and EP4, EP1 and EP3 receptors are involved in PGE2-induced COX-2 expression in lung adenocarcinoma. This discrepancy between colon cancer and lung adenocarcinoma could be due to the variations in expression profiles of EP receptors across different tumor types. Indeed, unlike in lung adenocarcinoma cells, EP1 and EP3 mRNA and protein expression levels are at almost undetectable levels in LoVo colon cancer cells.12

In this study, we also investigated the underlying mechanism by which PGE2-induces COX-2 expression in lung cancer cells. In our experiments, PGE2 activated the PKA-CREB and PI3K-AKT pathways. Furthermore, inhibition of PKA reduced the activation of CREB, and downregulation of CREB suppressed PGE2-induced COX-2 expression. Mechanistic analysis revealed that PGE2 stimulation enhanced the binding of CREB to the COX-2 promoter, and subsequently the expression of COX-2. More importantly, in our study, we show, for the first time, that the inhibition of PI3K-AKT signaling also affects PGE2-induced CREB phosphorylation. As a consequence, PI3K or AKT inhibitors suppress PGE2-induced COX-2 expression. Recently, a number of studies have identified actions of H89 that are independent of their effects on PKA. Its nonspecific effects include actions on other protein kinases, signaling molecules, and also on basic cellular functions such as transcription.22 For this reason, in this study, we used a PI3K inhibitor to explore the possibility of preventing the protumor effects of PGE2-COX-2 axis.

Identifying the PGE2-mediated positive feedback loop and its underlying responsible signaling pathway has potential clinical applications. COX-2 has long been considered as a valuable candidate for cancer therapy, but several clinical trials using COX-2 inhibitors in combination with chemotherapy to treat NSCLC have failed to improve overall survival and progression-free survival.5,21,23,24 Additionally, there is concern for cardiovascular and hematologic toxicities of COX-2 inhibitors.5 In our study, we show, for the first time, that inhibition of AKT activation blocks PGE2-induced COX-2 expression as well as suppresses PGE2-induced cell proliferation and migration. The combination of inhibitors for COX-2 and AKT resulted in a greater, synergistic effect on the suppression of PGE2-induced cell proliferation and migration. Thus, our findings provide a potential therapeutic target via inhibition of AKT activity to block the PGE2-induced positive feedback loop and thereby improve the efficacy of COX-2 inhibition.

Acknowledgment

All of the authors would like to acknowledge Adam Stanley (graduate student in our laboratory) for proofreading our manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers 81672808, 81472652, and 81874168 for L.L.).

Disclosure

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest for this work.

References

- 1.Achiwa H, Yatabe Y, Hida T, et al. Prognostic significance of elevated cyclooxygenase 2 expression in primary, resected lung adenocarcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(5):1001–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khuri FR, Wu H, Lee JJ, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression is a marker of poor prognosis in stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(4):861–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dohadwala M, Batra RK, Luo J, et al. Autocrine/paracrine prostaglandin E2 production by non-small cell lung cancer cells regulates matrix metalloproteinase-2 and CD44 in cyclooxygenase-2-dependent invasion. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(52):50828–50833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210707200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hennequart M, Pilotte L, Cane S, et al. Constitutive IDO1 expression in human tumors is driven by cyclooxygenase-2 and mediates intrinsic immune resistance. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017;5(8):695–709. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou YY, Hu ZG, Zeng FJ, Han J, Rosell R. Clinical profile of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in treating non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of nine randomized clinical trials. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151939. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breyer RM, Bagdassarian CK, Myers SA, Breyer MD. Prostanoid receptors: subtypes and signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41(1):661–690. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaki T, Endoh K, Miyahara M, et al. Prostaglandin E2 activates Src signaling in lung adenocarcinoma cell via EP3. Cancer Lett. 2004;214(1):115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhong X, Fan Y, Ritzenthaler JD, et al. Novel link between prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and cholinergic signaling in lung cancer: the role of c-Jun in PGE2-induced alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression and tumor cell proliferation. Thorac Cancer. 2015;6(4):488–500. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JI, Lakshmikanthan V, Frilot N, Daaka Y. Prostaglandin E2 promotes lung cancer cell migration via EP4-βArrestin1-c-Src signalsome. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8(4):569–577. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho MY, Liang SM, Hung SW, Liang CM. MIG-7 controls COX-2/PGE2-mediated lung cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013;73(1):439–449. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faour WH, Gomi K, Kennedy CR. PGE(2) induces COX-2 expression in podocytes via the EP(4) receptor through a PKA-independent mechanism. Cell Signal. 2008;20(11):2156–2164. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu -H-H, Lin Y-M, Shen C-Y, et al. Prostaglandin E2-induced COX-2 expressions via EP2 and EP4 signaling pathways in human LoVo colon cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(6):1132. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim HB, Kim M, Park YS, et al. Prostaglandin E2 activates YAP and a positive-signaling loop to promote colon regeneration after colitis but also carcinogenesis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(3):616–630. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ravindranathan P, Lee TK, Yang L, et al. Peptidomimetic targeting of critical androgen receptor-coregulator interactions in prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 2013;4(1):1923. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sobolewski C, Cerella C, Dicato M, Ghibelli L, Diederich M. The role of cyclooxygenase-2 in cell proliferation and cell death in human malignancies. Int J Cell Biol. 2010;2010:215158. doi: 10.1155/2010/215158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayr B, Montminy M. Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(8):599–609. doi: 10.1038/35085068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conkright MD, Montminy M. CREB: the unindicted cancer co-conspirator. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15(9):457–459. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin J, Sampath D, Nannini MA, et al. Targeting activated Akt with GDC-0068, a novel selective Akt inhibitor that is efficacious in multiple tumor models. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(7):1760–1772. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du K, Montminy M. CREB is a regulatory target for the protein kinase Akt/PKB. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(49):32377–32379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edelman MJ, Wang X, Hodgson L, et al. Phase III randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of celecoxib in addition to standard chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression: CALGB 30801 (alliance). J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(19):2184–2192. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.3743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Groen HJM, Sietsma H, Vincent A, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled phase iii study of docetaxel plus carboplatin with celecoxib and cyclooxygenase-2 expression as a biomarker for patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: the NVALT-4 study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4320–4326. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.5214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray AJ. Pharmacological PKA inhibition: all may not be what it seems. Sci Signal. 2008;1(22):re4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.122re4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch A, Bergman B, Holmberg E, et al. Effect of celecoxib on survival in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a double blind randomised clinical phase III trial (CYCLUS study) by the Swedish lung cancer study group. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(10):1546–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edelman MJ, Tan MT, Fidler MJ, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter Phase II study of the efficacy and safety of apricoxib in combination with either docetaxel or pemetrexed in patients with biomarker-selected non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(2):189–194. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.5789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]