Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which originated in Wuhan, China, in 2019, is responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. It is now accepted that the wild fauna, probably bats, constitute the initial reservoir of the virus, but little is known about the role pets can play in the spread of the disease in human communities, knowing the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to infect some domestic animals. In this cross-sectional study, we tested the antibody response in a cluster of 21 domestic pets (9 cats and 12 dogs) living in close contact with their owners (belonging to a veterinary community of 20 students) in which two students tested positive for COVID-19 and several others (n = 11/18) consecutively showed clinical signs (fever, cough, anosmia, etc.) compatible with COVID-19 infection. Although a few pets presented many clinical signs indicative for a coronavirus infection, no antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were detectable in their blood one month after the index case was reported, using an immunoprecipitation assay. These original data can serve a better evaluation of the host range of SARS-CoV-2 in natural environment exposure conditions.

Keywords: COVID-19 epidemiology, Outbreak, Self-isolation, Feline, Canine, Luciferase immunoprecipitation system, LIPS

1. Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 infection has presented unprecedented challenges related to viral disease control and prevention worldwide. While the emergence of the virus is now well-documented, important questions regarding the transmissibility of the disease among human populations remain to be answered. SARS-CoV-2 might infect animals [1], including dogs, cats, ferrets [[2], [3], [4]] or minks [5]. Therefore, the hypothesis that small domestic animals could serve as intermediate or amplification hosts of the virus needs to be further addressed in a One Health approach [6,7]. To increase the knowledge regarding transmission rates in circumstances of contamination that ensure efficient human-to-human transmission, we have investigated the infection status of dogs and cats living in close proximity with a cluster of veterinary students who developed COVID-19 symptoms in Winter 2019–2020, i.e. during the initial phase of the first wave of the pandemic in France.

2. Methods

We investigated the presence of SARS-CoV-2 infection of domestic cats (n = 9) and dogs (n = 12) living in close contact with a cluster of French veterinary students, their owners (n = 18), whose median age was 23 years (21–28 years). 14/18 students lived in university residences with common traffic areas and daily outdoor activities to allow animals, especially dogs, to relieve themselves in spaces that were shared by all animals. The other four students lived outside the residence, with reduced contact during lockdown, except for one student who lived with a roommate. All 18 students had contact with at least one sick person within three weeks prior sampling and 11 of them developed symptoms compatible with COVID-19 between February 25th and March 18th, 2020. The symptoms were mainly cough, with or without fever. Headaches, dyspnea and dizziness were reported for one case. Among symptomatic students, two were tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR. The other nine symptomatic patients were not tested in accordance with French regulations that, at the time of sampling, did not request to test all patients in such clusters. Other owners (7/18) were asymptomatic at the time of sampling. All of the owners were in the close vicinity of their pets, e.g. living in the same room – of 12 to 17 square meters - and sharing the same bed (8/8 of cats' owners and 4/12 of dog's owners); accepting face/hand licking (6/8 and 11/12 of cats' and dogs' owners, respectively). All cats were domestic European Shorthair cats. Dogs included in the sampled panel were either cross-bred (n = 6) or purebred individuals from the Labrador Retriever, Shetland Sheepdog, Belgian Malinois and White Swiss Shepherd breeds (n = 6). The average age of these sampled adult animals was 3.3 years for cats (min: 6 months; max: 6.5 years) and 2.7 years for dogs (min: 4 months; max: 8 years). Small pets were free of clinical signs, except some respiratory or digestive signs reported for three cats, independently.

Sera from this per-epidemic cohort of pets (hereafter named “pets epidemic”, n = 21) were freshly prepared from blood collected on March 25th, one month after the index case. A panel of biobanked sera was also obtained from a second cohort (named “pets pre-epidemic” n = 62), composed of animals sampled before the COVID-19 pandemic - between October 2015 and October 2018, containing 55 dogs from 32 popular breeds and seven cats including five European Shorthair, one Turkish Angora and one Devon rex.

The search for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 was carried out on the 79 sera of the two cohorts using a Luciferase Immuno-Precipitation System (LIPS) assay validated and used previously [[8], [9], [10], [11]], using two antigens: (i) the S1 domain of the SARS-CoV-2 S spike protein and (ii) the C-terminal part (residues 233–419) of the SARS-CoV-2 N nucleoprotein [12]. Viral antigens were produced in HEK-293F cells transfected with plasmids expressing the gene for Nanoluc fused to the C-terminus of the viral protein. Recombinant proteins were harvested from the supernatant (S1, which is a surface glycoprotein secreted in culture supernatant) or cell lysate (N, which is located inside the virus) without any purification step and incubated with 10 μL of animal serum. The immune complexes were precipitated with protein A/G-coated beads, washed, and the luciferase activity was monitored on a Centro XS3 LB 960 luminometer (Berthold Technologies, France). The positivity threshold was defined as the mean of 10 negative controls (without serum) + five standard deviations. Human patients' sera collected before and during the course of the epidemic were used as negative and positive controls respectively. The LIPS assay was initially designed to maximize the specificity of the test (>95%) to ensure that human seasonal HCoV were not detected when searching for SARS-CoV-2 Ab, assuming a lower sensitivity. The sensitivity of the LIPS assay has been evaluated in mildly symptomatic humans as 91.4% when compared to the very sensitive cytometric assay [8].

3. Results

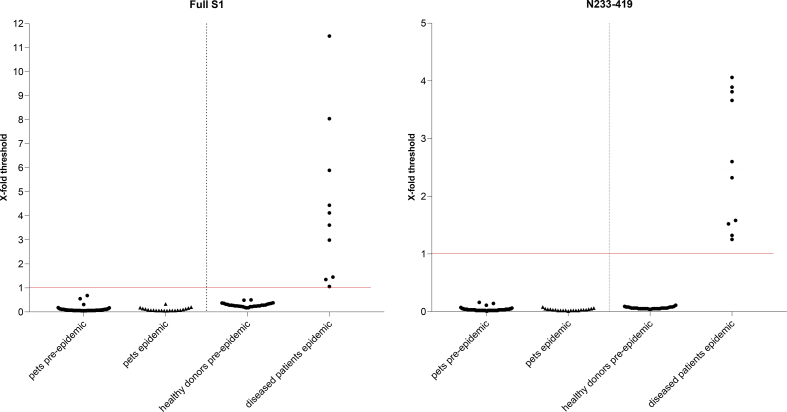

SARS-CoV-2 specific antibodies were not detected in the “pets epidemic” cohort, and no statistical difference was observed compared to the “pets pre-epidemic” cohort (Fig. 1). In addition, late nasal and rectal swabs were taken during one week, starting from the day of blood sampling (March 25th) and all animals tested negative for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR (who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/whoinhouseassays.pdf). We concluded that none of the animals included in this study had been or was infected by SARS-CoV-2, despite repeated close intra-species daily contacts on the campus, and more importantly despite frequent and lasting contacts with COVID-19 patients confined to small rooms.

Fig. 1.

LIPS assay targeting antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in domestic cats and dogs in close contact with a cluster of COVID-19 patients.

Sera from pets in contact with COVID-19 patients (pets epidemic, n = 21); from pets sampled before the epidemic (pets pre-epidemic, n = 62) were tested for the presence of antibodies directed to S1 (left panel) and the C-term (residues 233–419) part of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein (right panel), using a luciferase immunoprecipitation system assay (LIPS). The same assay was performed for humans unrelated to this study, either COVID-19 human patients (symptomatic human patients epidemic, n = 10) or healthy volunteers blood donors (healthy donors pre-epidemic; n = 30).

4. Discussion

Several studies have investigated the susceptibility of domestic animals and their putative role in the current COVID-19 pandemic (review in [1]). Ferrets, in particular, are used for modeling SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans [2], understanding the route of transmission [13] and developing therapeutic strategies [14].

Among seven domestic animal species tested, Shi et al. [3] have demonstrated that ferrets, cats and dogs can be experimentally infected by the intranasal route, probably through the viral receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). Accordingly, it has been recently demonstrated that ACE2 from these species, as well as from others known to support SARS-CoV-2 infection, tolerates many amino acid changes with no decrement in its receptor function, a feature that predicts a low species barrier [15]. Interestingly, key ACE2 residues that distinguish susceptible from resistant species have been identified by Alexander et al. [16], in a scoring model that may also explain the highly contagious nature of the virus among humans. Dogs, that express low levels of ACE2 in the respiratory tract [15], had a susceptibility score of 23 in the work of Alexander et al. and were actually shown by Shi et al. to be less susceptible to experimental infection than cats, which had a SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility score of 27 [3,16]. Cats, during their juvenile post-weaning life (70–100 days), appear to be more vulnerable than older ones [3]. Shi et al. also reported that one out of three naïve cats exposed to infected cats became infected, showing that intra-species respiratory droplet transmission can occur in cats, at least from cats experimentally infected with 105 PFU by the intranasal route [3]. Nasal shedding and subsequent transmission of the virus by direct contact between virus-inoculated cats has also been reported in asymptomatic cats by Halfman et al. [17].

Consistent with the increased susceptibility of this domesticated species, a study of 102 pet cats living in Wuhan, China, and collected in the first quarter of 2020 during the pandemic period, has reported a prevalence of 14.7% seroconverted cats, with cats owned by COVID-19 patients (presumably adults cats) having the highest neutralization titers [18]. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies have also been found in two cats and one dog among 10 cats and nine dogs recruited from COVID-19 patients admitted to Wuhan Hospital in March 2020 [19]. On the other hand, a serological survey conducted in China in companion and street cats (n = 87) and dogs (n = 487) sampled from November 2019 to March 2020 has shown no detectable SARS-CoV-2 specific antibodies [20]. In the latter work, one dog was owned by a SARS-CoV-2 patient and two dogs were in close contact with it during the quarantine. In a collaborative work, we have described in Belgium the first case in cat, identified in March, presenting with diarrhea followed by an acute respiratory syndrome [21]. In the United States, the first two domestic cats displaying respiratory illnesses alongside with SARS-CoV-2 infection were reported in April 2020 [22]. Both cats were owned by persons with suspected or confirmed COVID-19. In France, one cat with mild respiratory and digestive signs tested positive by RT-qPCR on rectal swab (but not on nasopharyngeal swab) with antibodies detected in the serum [23]. This case was reported from a series of 22 cats and 11 dogs whose owners were suspected or confirmed positive for COVID-19. Altogether, these results and the present finding highlight that natural infection of cats is possible but remains a rare event. Consequently, the success of detecting SARS-CoV-2 seropositive pets seems to be linked to well-defined narrowed human/pets interfaces.

Although based on a small cluster of 21 domestic pets, our cross-sectional study based on the antibody response one month after exposure to the index case points to undetectable interspecific transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus between COVID-19 patients and domestic dogs or cats under natural exposure conditions. To support the absence of asymptomatic long portage in seronegative animals, late PCRs (sampling starting from March 25th) had been performed and were negative. Given the susceptibility of cats inoculated intranasally with 105 PFU or by direct aerosol transmission from infected cats [3,17], it is conceivable that the infected and seroconverted cats identified in Wuhan, China [18,19], had either been in contact with patients whose viral load was higher than in our study (which is supported by the fact that patients were hospitalized, conversely to our study in which positive students presented mild symptoms), or have had more contacts with infected cats. These questions among others will need to be further addressed.

Therefore, despite the susceptibility of some animal species revealed in observational or experimental conditions and making the juvenile cat, in particular, a potential model of SARS-CoV-2 replication, our results support evidence for a nil or very low COVID-19 rate of infection in companion dogs and cats, even in a situation of repeated contacts and close proximity to infected humans. This suggests that the rate of SARS-CoV-2 transmission between humans and pets in natural conditions is probably low, below a reproduction number of 1. Replication studies to accurately characterize a possible role of pets, and especially feline, as an intermediate host vector of SARS-CoV-2, are needed in different international contexts. This should include larger populations and the study of the role of the age of the animals and of the surrounding viral load, such as recently surveyed in northern Italy at a time of frequent human infection [24].

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We also thank funding from Institut Pasteur, Labex IBEID (ANR-10-LABX-62-IBEID), REACTing (Research & Action Emerging Infectious Diseases), Cani-DNA BRC that is part of the CRB-Anim infra-structure, ANR-11-INBS-0003 and EU Grant 101003589 RECoVER.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: ST, ME; Formal analysis: ST, ME, PP; Funding acquisition: ME; Investigation: ST, AB, DM, SB, VE, CH, AJ, LC, PV, LT, SVW; Methodology: ST, MB, ME; Supervision: ME; Roles/Writing - original draft: PP; Writing - review & editing: LT, PP, ME, ST.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Abdel-Moneim A.S., Abdelwhab E.M. Evidence for SARS-CoV-2 infection of animal hosts. Pathogens. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/pathogens9070529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim Y.-I., Kim S.-G., Kim S.-M., Kim E.-H., Park S.-J., Yu K.-M., Chang J.-H., Kim E.J., Lee S., Casel M.A.B., Um J., Song M.-S., Jeong H.W., Lai V.D., Kim Y., Chin B.S., Park J.-S., Chung K.-H., Foo S.-S., Poo H., Mo I.-P., Lee O.-J., Webby R.J., Jung J.U., Choi Y.K. Infection and rapid transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in ferrets. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:704–709.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi J., Wen Z., Zhong G., Yang H., Wang C., Huang B., Liu R., He X., Shuai L., Sun Z., Zhao Y., Liu P., Liang L., Cui P., Wang J., Zhang X., Guan Y., Tan W., Wu G., Chen H., Bu Z. Susceptibility of ferrets, cats, dogs, and other domesticated animals to SARS-coronavirus 2. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abb7015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sit T.H.C., Brackman C.J., Ip S.M., Tam K.W.S., Law P.Y.T., E.M.W. To, Yu V.Y.T., Sims L.D., Tsang D.N.C., Chu D.K.W., Perera R.A.P.M., Poon L.L.M., Peiris M. Infection of dogs with SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2334-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oreshkova N., Molenaar R.J., Vreman S., Harders F., Oude Munnink B.B., Hakze-van der Honing R.W., Gerhards N., Tolsma P., Bouwstra R., Sikkema R.S., Tacken M.G., de Rooij M.M., Weesendorp E., Engelsma M.Y., Bruschke C.J., Smit L.A., Koopmans M., van der Poel W.H., Stegeman A. SARS-CoV-2 infection in farmed minks, the Netherlands, April and may 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.23.2001005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leroy E.M., Ar Gouilh M., Brugère-Picoux J. The risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to pets and other wild and domestic animals strongly mandates a one-health strategy to control the COVID-19 pandemic. One Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Zowalaty M.E., Järhult J.D. From SARS to COVID-19: a previously unknown SARS- related coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) of pandemic potential infecting humans – call for a one health approach. One Health. 2020;9 doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grzelak L., Temmam S., Planchais C., Demeret C., Tondeur L., Huon C., Guivel-Benhassine F., Staropoli I., Chazal M., Dufloo J., Planas D., Buchrieser J., Rajah M.M., Robinot R., Porrot F., Albert M., Chen K.-Y., Crescenzo-Chaigne B., Donati F., Anna F., Souque P., Gransagne M., Bellalou J., Nowakowski M., Backovic M., Bouadma L., Fevre L.L., Hingrat Q.L., Descamps D., Pourbaix A., Laouénan C., Ghosn J., Yazdanpanah Y., Besombes C., Jolly N., Pellerin-Fernandes S., Cheny O., Ungeheuer M.-N., Mellon G., Morel P., Rolland S., Rey F.A., Behillil S., Enouf V., Lemaitre A., Créach M.-A., Petres S., Escriou N., Charneau P., Fontanet A., Hoen B., Bruel T., Eloit M., Mouquet H., Schwartz O., van der Werf S. A comparison of four serological assays for detecting anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in human serum samples from different populations. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abc3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Temmam S., Chrétien D., Bigot T., Dufour E., Petres S., Desquesnes M., Devillers E., Dumarest M., Yousfi L., Jittapalapong S., Karnchanabanthoeng A., Chaisiri K., Gagnieur L., Cosson J.-F., Vayssier-Taussat M., Morand S., Moutailler S., Eloit M. Monitoring silent Spillovers before emergence: a pilot study at the tick/human Interface in Thailand. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:2315. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.A. Fontanet, L. Tondeur, Y. Madec, R. Grant, C. Besombes, N. Jolly, S.F. Pellerin, M.-N. Ungeheuer, I. Cailleau, L. Kuhmel, S. Temmam, C. Huon, K.-Y. Chen, B. Crescenzo, S. Munier, C. Demeret, L. Grzelak, I. Staropoli, T. Bruel, P. Gallian, S. Cauchemez, S. van der Werf, O. Schwartz, M. Eloit, B. Hoen, Cluster of COVID-19 in northern France: A retrospective closed cohort study, MedRxiv. (2020) 2020.04.18.20071134. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.18.20071134. [DOI]

- 11.I. Sermet, S. Temmam, C. Huon, S. Behillil, V. Gadjos, T. Bigot, T. Lurier, D. Chretien, M. Backovick, A. Moisan-Delaunay, F. Donati, M. Albert, E. Foucaud, B. Mesplees, G. Benoist, A. Fayes, M. Duval-Arnould, C. Cretolle, M. Charbit, M. Aubart, J. Auriau, M. Lorrot, D. Kariyawasam, L. Fertita, G. Orliaguet, B. Pigneur, B. Bader-Meunier, C. Briand, J. Toubiana, T. Guilleminot, S.V.D. Werf, M. Leruez-Ville, M. Eloit, Prior infection by seasonal coronaviruses does not prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection and associated Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in children, MedRxiv. (2020) 2020.06.29.20142596. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.29.20142596. [DOI]

- 12.Andersen K.G., Rambaut A., Lipkin W.I., Holmes E.C., Garry R.F. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Med. 2020;26:450–452. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richard M., Kok A., de Meulder D., Bestebroer T.M., Lamers M.M., Okba N.M.A., Fentener van Vlissingen M., Rockx B., Haagmans B.L., Koopmans M.P.G., Fouchier R.A.M., Herfst S. SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted via contact and via the air between ferrets. Nat. Commun. 2020;11 doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17367-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.S.-J. Park, K.-M. Yu, Y.-I. Kim, S.-M. Kim, E.-H. Kim, S.-G. Kim, E.J. Kim, M.A.B. Casel, R. Rollon, S.-G. Jang, M.-H. Lee, J.-H. Chang, M.-S. Song, H.W. Jeong, Y. Choi, W. Chen, W.-J. Shin, J.U. Jung, Y.K. Choi, Antiviral efficacies of FDA-approved drugs against SARS-CoV-2 infection in ferrets, MBio. 11 (2020). doi: 10.1128/mBio.01114-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Zhai X., Sun J., Yan Z., Zhang J., Zhao J., Zhao Z., Gao Q., He W.-T., Veit M., Su S. Comparison of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spike protein binding to ACE2 receptors from human, pets, farm animals, and putative intermediate hosts. J. Virol. 2020;94 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00831-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexander M.R., Schoeder C.T., Brown J.A., Smart C.D., Moth C., Wikswo J.P., Capra J.A., Meiler J., Chen W., Madhur M.S. Which animals are at risk? Predicting species susceptibility to Covid-19. BioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.07.09.194563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halfmann P.J., Hatta M., Chiba S., Maemura T., Fan S., Takeda M., Kinoshita N., Hattori S., Sakai-Tagawa Y., Iwatsuki-Horimoto K., Imai M., Kawaoka Y. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in domestic cats. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2013400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Q. Zhang, H. Zhang, K. Huang, Y. Yang, X. Hui, J. Gao, X. He, C. Li, W. Gong, Y. Zhang, C. Peng, X. Gao, H. Chen, Z. Zou, Z. Shi, M. Jin, SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing serum antibodies in cats: a serological investigation, BioRxiv. (2020) 2020.04.01.021196. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.01.021196. [DOI]

- 19.Chen J., Huang C., Zhang Y., Zhang S., Jin M. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2-specific antibodies in pets in Wuhan, China. J. Inf. Secur. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng J., Jin Y., Liu Y., Sun J., Hao L., Bai J., Huang T., Lin D., Jin Y., Tian K. Serological survey of SARS-CoV-2 for experimental, domestic, companion and wild animals excludes intermediate hosts of 35 different species of animals. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020;67:1745–1749. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garigliany M., Van Laere A.-S., Clercx C., Giet D., Escriou N., Huon C., van der Werf S., Eloit M., Desmecht D. SARS-CoV-2 natural transmission from human to cat, Belgium, march 2020. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2020;26 doi: 10.3201/eid2612.202223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman A., Smith D., Ghai R.R., Wallace R.M., Torchetti M.K., Loiacono C., Murrell L.S., Carpenter A., Moroff S., Rooney J.A., Barton Behravesh C. First reported cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in companion animals - New York, march-April 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2020;69:710–713. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sailleau C., Dumarest M., Vanhomwegen J., Delaplace M., Caro V., Kwasiborski A., Hourdel V., Chevaillier P., Barbarino A., Comtet L., Pourquier P., Klonjkowski B., Manuguerra J.C., Zientara S., Le Poder S. First detection and genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 in an infected cat in France. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1111/tbed.13659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patterson E.I., Elia G., Grassi A., Giordano A., Desario C., Medardo M., Smith S.L., Anderson E.R., Prince T., Patterson G.T., Lorusso E., Lucente M.S., Lanave G., Lauzi S., Bonfanti U., Stranieri A., Martella V., Basano F.S., Barrs V.R., Radford A.D., Agrimi U., Hughes G.L., Paltrinieri S., Decaro N. Evidence of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in cats and dogs from households in Italy. BioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.07.21.214346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]