Abstract

Background

Recent guidelines recommend that patients with immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) and proteinuria 0.5–1 g/d and >1 g/d be treated with long-term renin–angiotensin system blockade (RASB). This study investigated whether patients with IgAN and persistent hematuria, but without proteinuria, can benefit from RASB.

Material/Methods

IgAN patients with persistent hematuria at four centers were recruited from January 2013 to December 2018. Patients were divided into those who did and did not receive long-term RASB. The primary outcome was the appearance of proteinuria, and the secondary outcomes were the decreased percentage of hematuria, rate of decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and final blood pressure. The effects of RASB on these outcomes were assessed by multivariate Cox regression models and propensity score matching.

Results

Of the 110 eligible patients, 44 (40.0%) received RASB and 66 (60.0%) did not. Treated patients had higher diastolic pressure. The unadjusted primary outcome, the appearance of proteinuria, was significantly less frequent in individuals who were than who were not treated with RASB. Multivariate Cox regression showed that RASB reduced the risk of the primary outcome and the levels of hematuria. The rate of eGFR decline and final blood pressure did not differ in the two groups.

Conclusions

RASB reduced the risk of proteinuria development and increased the remission of hematuria in patients with IgAN who presented with persistent hematuria alone. RASB, however, did not affect blood pressure in patients without hypertension and did not affect the rate of eGFR decline.

MeSH Keywords: Glomerular Filtration Rate; Glomerulonephritis, IGA; Hematuria

Background

IgAN is the most common cause of primary glomerulonephritis in developed countries [1]. Current clinical treatment strategies for IgAN include renin–angiotensin system blockade (RASB) to control blood pressure and proteinuria and administration of glucocorticoids, with or without other immunosuppressive agents, to selected patients [2,3]. RASB is considered a first-line treatment of IgAN [4], with benefits that include the reduction of proteinuria and renal function decline, with most studies recruiting patients with proteinuria >0.5–1 g/d [5–9]. Clinically, patients with IgAN have received RASB to eliminate or reduce proteinuria, as well as to control hypertension [10]. The 2012 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcome (KDIGO) guidelines recommended the use of long-term RASB in patients with proteinuria >1 g/d and suggested its use if proteinuria is 0.5–1 g/d [4]. Proteinuria was found to be an important risk factor for poor patient prognosis [11–14]. Although a study assessing the efficacy of RASB in reducing the incidence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) recruited individuals with any level of proteinuria, subgroup analysis found that RASB had limited effect in IgAN patients with proteinuria <1 g/d [15]. This did not necessarily indicate that RASB was ineffective in these patients, because the incidence of ESRD was low in this subgroup. It remains unclear whether IgAN patients with persistent hematuria alone and initial proteinuria < 150 mg/d can benefit from RASB, as studies have suggested that regular observation was sufficient [16]. However, persistent and significant hematuria was recently reported to independently increase the risk of renal function loss, with remission of hematuria having a favorable effect on disease progression [17]. Because proteinuria also increases adverse renal outcomes, it is essential that IgAN patients with persistent hematuria alone avoid the development of proteinuria and reduce their levels of hematuria. The present study therefore investigated whether RASB can exert protective effect on IgAN patients who present with persistent hematuria alone and without proteinuria initially.

Material and Methods

Patients

Patients with biopsy-proven IgAN and persistent hematuria, but without proteinuria, were recruited between January 2013 and December 2018 at four hospitals, including Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, the Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University and People’s Hospital of Hunan Province. Patients were included if they had primary IgAN and persistent hematuria alone. Unless they developed proteinuria, individuals were followed up for more than six months. Patients were excluded if they had secondary IgAN (e.g. secondary to purpura nephritis, lupus nephritis, hepatitis B associated glomerulonephritis), systemic diseases, or crescentic IgAN (>50% crescentic glomeruli). Patients were also excluded if they had received immunosuppression therapy (corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine or tacrolimus) within 1 year or during follow-up, or if they were lost to follow up. Patients were divided into two groups, those who were and were not treated with RASB. All patients were followed up until June 2019.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital of Central South University and at all other centers and was performed in compliance with the principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Baseline characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of all enrolled individuals were obtained from the electronic medical records systems of the respective institutions. Baseline characteristics recorded included gender; age; uric acid and hemoglobin concentrations; serum creatinine and albumin levels; level of hematuria; initial eGFR; systolic and diastolic blood pressure; and Oxford classification, including mesangial hypercellularity (M), endocapillary hypercellularity (E), segmental glomerulosclerosis (S), tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis (T) scores and crescents (C) [22]. Also recorded were use of RASB and duration from initial diagnosis by biopsy to the start of therapy.

Definitions

Absence of proteinuria was defined as protein excretion ≤150 mg/d before renal biopsy. Levels of urinary protein were repeatedly confirmed twice. Appearance of proteinuria was defined as urinary protein >150 mg/d, with no recovery in the absence of treatment. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg [18]. eGFR was calculated using the CKD-EPI equation [19]. Hypoalbuminemia was defined as serum albumin ≤35 g/L [20]; and hyperuricemia as serum uric acid level >416 μmol/L in men and >360 μmol/L in women [21]. RASB included treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) or angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) during the follow-up period before proteinuria appeared.

The primary outcome was defined as the appearance of proteinuria. The secondary outcomes were the decreased percentage of hematuria, the rate of eGFR decline during follow-up and final blood pressure.

Treatment strategy

Treated patients were administered oral low-dose RASB, consisting of 1–2 tablets/d of benazepril, perindopril, valsartan or losartan, alone or in combination, before the appearance of proteinuria, with the dosage adjusted individually based on blood pressure and serum creatinine concentrations.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages and compared by Chi square tests or Fisher exact tests. Continuous variables are expressed as means±standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) and compared by t tests or Mann-Whitney U tests. Time to the primary outcome was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was used to assess the role of RASB in the primary outcome. Because this study was designed retrospectively and the initial diastolic pressure was higher in the treatment group (Table 1), individuals who did and did not receive RASB were at different risks of progression. To better compare the decreases in the percentage of hematuria and the rates of eGFR decline, propensity score matching was performed. A logistic regression model was used to predict the probability of RASB treatment for every patient. Propensity scores were estimated using a model that included variables such as initial eGFR, serum uric acid, initial systolic pressure, initial diastolic pressure and MESTC scores. Patients who were and were not treated with RASB were matched by closest scores (±0.05). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (22.0, IBM), with a two-tailed P<0.05 indicating statistical significance.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of IgAN patients only with persistent hematuria initially (n=110).

| Characteristics at biopsy | All (n=110) | Treatment group (n=44) | Untreated group (n=66) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Male (%) | 29 (26.4) | 12 (27.3) | 17 (25.8) | 0.86 |

| Age (years) | 30±11 | 32±11 | 29±10 | 0.16 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 71.0 (59.0–81.0) | 72.0 (59.0–86.0) | 71.0 (58.8–77.5) | 0.26 |

| Initial eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 105.5±24.4 | 102.0±22.9 | 107.9±25.2 | 0.21 |

| Hematuria, (cells/hpf) | 34.0 (17.0–66.0) | 36.0 (24.0–65.0) | 33.0 (13.0–68.0) | 0.31 |

| Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 120 (107–127) | 120 (109–128) | 118 (104–124) | 0.21 |

| Diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 75 (68–83) | 78 (70–85) | 71 (65–80) | 0.03 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 11 (10.0) | 6 (13.6) | 5 (7.6) | 0.34 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 127 (118–134) | 127 (117–133) | 127 (117–134) | 0.95 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 41.9±4.5 | 41.6±4.6 | 42.1±4.4 | 0.53 |

| Uric acid (μmol/L) | 281 (249–321) | 281 (229–342) | 283 (255–309) | 0.75 |

| Low hemoglobin, n (%) | 13 (11.8) | 5 (11.4) | 8 (12.1) | 0.90 |

| Hypoalbuminemia, n (%) | 6 (5.5) | 3 (6.8) | 3 (4.5) | 0.68 |

| Hyperuricemia, n (%) | 13 (11.8) | 6 (13.6) | 7 (10.6) | 0.63 |

| Biopsy characteristics | ||||

| M1, n (%) | 57 (51.8) | 27 (61.4) | 30 (45.5) | 0.10 |

| E1, n (%) | 24 (21.8) | 8 (18.2) | 16 (24.2) | 0.45 |

| S1, n (%) | 38 (34.5) | 18 (40.9) | 20 (30.3) | 0.12 |

| T1–2, n (%) | 7 (6.4) | 2 (4.5) | 5 (7.6) | 0.70 |

| C1–2, (%) * | 12 (10.9) | 8 (18.2) | 4 (6.1) | 0.06 |

| Duration from initial diagnosis to start of therapy (months) | 5.0 (1.0–12.0) | 4.5 (1.0–16.5) | 5.6 (1.0–12.0) | 0.96 |

Crescents >50% were excluded.

eGFR – estimated glomerular filtration rate; RASB – reninangiotensin system blockers; M – mesangial hypercellularity; E – endocapillary hypercellularity; S – segmental glomerulosclerosis; T – tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis; C – crescent.

Results

Patients and baseline characteristics

This study recruited 110 patients, 29 (26.4%) men and 81 (73.6%) women, of mean age 30±11 years. Of these 110 patients, 44 (40.0%) did and 66 (60.0%) did not receive RASB treatment before the development of proteinuria. The mean±SD initial eGFR was 105.5±24.4 ml/min/1.73 m2 and the median (IQR) hematuria was 34.0 (17.0–66.0) cells per high powered field (hpf). According to the Oxford classification, 51.8%, 21.8%, 34.5%, 6.4% and 10.9% of these patients were pathologically characterized as M1, E1, S1, T1–2 and C1–2, respectively. Diastolic blood pressure was significantly higher in patients with than without RASB (p=0.03). All other characteristics (gender, age, serum creatinine, initial eGFR, systolic pressure, low hemoglobin, hypoalbuminemia, hyperuricemia, and Oxford classifications of M1, E1, S1, T1–2 and C1–2) were similar in the two groups (Table 1).

Follow up and outcome

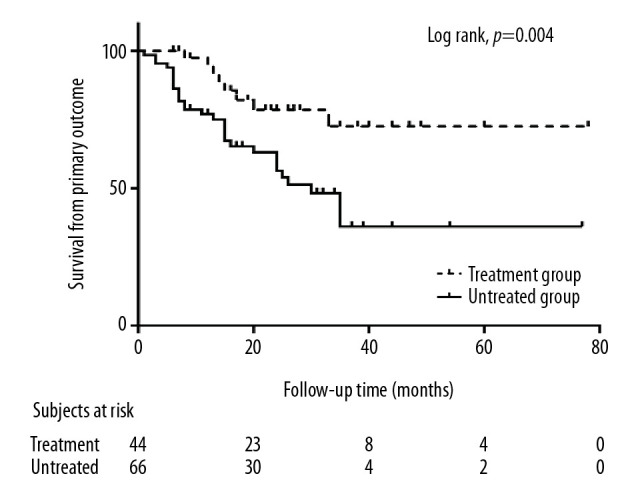

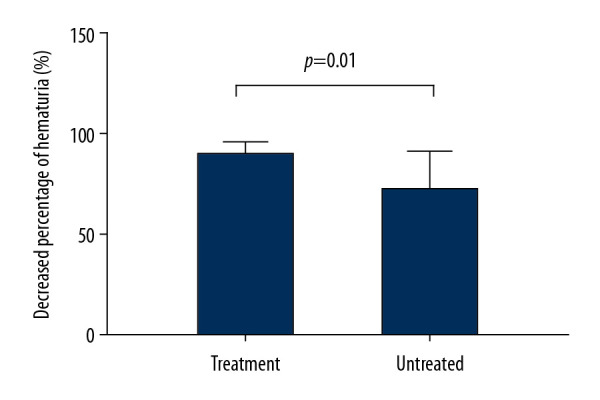

The follow-up time was 24.0 (12.8–36.3) months, without significant difference between the two groups. The proportion of individuals who progressed to proteinuria was significantly higher in the untreated than in the treated group (p=0.003), and unadjusted Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that the progression to the primary outcome was significantly slower for patients with RASB than without (Log-rank, p=0.004) (Figure 1). The difference between hematuria at the start and end of follow up was significant in the groups who did (paired t test, p=0.01) and did not (paired t test, p=0.03) receive RASB. The decreased percentage of hematuria was significantly higher (p=0.01, Figure 2) and the final level of hematuria was lower (p=0.049) in the treated than in the untreated group (Table 2). However, final eGFR, the rate of eGFR decline, and final systolic and diastolic blood pressure were similar in the two groups.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of survival in RASB treated and untreated patients. Progression to the primary outcome differed significantly (log-rank, p=0.004). RASB, rennin-angiotensin system blockers

Figure 2.

Effect of RASB on the decreased percentage of hematuria. The decreased percentage of hematuria was significantly higher in RASB treated than untreated patients (p=0.01). RASB, rennin-angiotensin system blockers.

Table 2.

Outcomes of treated and untreated IgAN patients only with persistent hematuria initially (n=110).

| Outcomes | All | Treatment group | Untreated group | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome (n, %)* | 38 (34.5) | 8 (18.2) | 30 (45.5) | 0.003 |

| Final eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 107.1±24.2 | 106.0±22.1 | 107.8±25.6 | 0.71 |

| Hematuria change from start to end of follow-up (cells/hpf)** | 35.0±102.1 | 48.7±110.0 | 25.9±96.2 | 0.01/0.03# |

| Final hematuria (cells/hpf) | 4.5 (1.7–19.2) | 3.6 (1.7–6.2) | 5.9 (1.7–29.3) | 0.049 |

| Decreased percentage of hematuria (%) | 82 (21–94) | 90 (72–96) | 72 (6–91) | 0.01 |

| Rate of eGFR decline (ml/min per 1.73 m2/y) | 0.51 (−3.98–5.35) | 1.04 (−1.66–4.41) | −0.05 (−4.73–5.58) | 0.38 |

| Final systolic pressure (mmHg) | 115 (110–122) | 118 (110–125) | 115 (107–121) | 0.38 |

| Final diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 75 (65–81) | 76 (74–85) | 69 (63–80) | 0.17 |

| Follow-up time (for the primary outcome, months) | 18.0 (10.5–30.0) | 21 (12.0–34.5) | 16.5 (8.0–27.0) | 0.11 |

| Follow-up time (for the whole follow-up periods, months)## | 24.0 (12.8–36.3) | 24.5 (12.5–38.0) | 24.0 (12.8–32.0) | 0.28 |

Appearance of proteinuria;

initial hematuria – final hematuria;

paired t test;

all patients were followed up until June 2019 whether progressed to the primary endpoint or not.

eGFR – estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Benefits of RASB to the primary outcome

The effect of RASB on the primary outcome was analyzed in four multivariate Cox regression models. In model 1, in which the hazard ratio (HR) was adjusted by gender and age, RASB had a significant benefit (HR=0.34, 95% CI: 0.16–0.75, p=0.01). In model 2, in which HR was adjusted by gender, age, hypertension, hyperuricemia, initial eGFR, duration from initial diagnosis to start of therapy and initial hematuria, RASB also had a significant effect on the primary outcome (HR=0.28, 95% CI: 0.12–0.65, p=0.003). In model 3, in which HR was adjusted by factors in Model 2 and Oxford classification factors, RASB was still associated with a better outcome (HR=0.22, 95% CI: 0.09–0.53, p=0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis for the effect of RASB on the primary outcome of IgAN patients only with persistent hematuria initially.

| Models | All (n=110) | P | Patients without hypertension (n=99) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |||

| Model 1* | ||||

| With RASB | 0.34 (0.16–0.75) | 0.01 | 0.23 (0.09–0.59) | 0.002 |

| Without RASB | Reference | – | – | – |

| Model 2** | ||||

| With RASB | 0.28 (0.12–0.65) | 0.003 | 0.21 (0.08–0.55) | 0.002 |

| Without RASB | Reference | – | – | – |

| Model 3*** | ||||

| With RASB | 0.22 (0.09–0.53) | 0.001 | 0.17 (0.06–0.46) | 0.001 |

| Without RASB | Reference | – | – | – |

Adjusted by gender and age;

adjusted by gender, age, hypertension, hyperuricemia, initial eGFR, duration from initial diagnosis to start of therapy and initial hematuria;

Model 2+Oxford classification factors (M, E, S, T and C).

RASB – renin–angiotensin system blockers; HR – hazard ratio; CI – confidence interval.

Excluding patients with hypertension, the benefits of RASB on the primary outcome remained applicable to patients without hypertension (Table 3).

Benefits of RASB to the secondary outcomes

The benefits of RASB on the decreased percentage of patients with hematuria and the rate of eGFR decline were analyzed following propensity score matching. Thirty-seven patients who received RASB were matched with 66 patients who did not, essentially eliminating any differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups (Supplementary Table 1). The decreased percentage of hematuria of RASB treated individuals was 93 (IQR, 74–96), which was much higher than the untreated patients (p=0.01, Table 4). However, rates of eGFR decline and final blood pressure were similar in the two groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Secondary outcomes of propensity-matched patients (n=103).

| Outcomes | Treatment group | Untreated group | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| All (n=103) | |||

| Decreased percentage of hematuria (%) | 93 (74–96) | 72 (–6–91) | 0.01 |

| Rate of eGFR decline (ml/min per 1.73 m2/y) | 0.78 (−1.95–4.36) | 0.05 (−4.73–5.58) | 0.48 |

| Final systolic pressure (mmHg) | 118 (110–125) | 115 (107–121) | 0.38 |

| Final diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 76 (74–85) | 69 (63–80) | 0.17 |

| Patients without hypertension (n=93) | |||

| Decreased percentage of hematuria (%) | 91 (73–96) | 71 (–22–91) | 0.01 |

| Rate of eGFR decline (ml/min per 1.73 m2/y) | 0.69 (−1.66–4.41) | −0.05 (−4.77–5.47) | 0.37 |

| Final systolic pressure (mmHg) | 118 (110–124) | 115 (106–121) | 0.45 |

| Final diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 76 (71–80) | 70 (65–80) | 0.48 |

eGFR – estimated glomerular filtration rate.

When patients with hypertension were excluded, RASB still showed benefits in reducing hematuria in patients without hypertension, with the final systolic and diastolic pressure remaining similar in these two groups (Table 4).

Discussion

Treatment strategies are sought to delay the progression of IgAN [23]. Studies have therefore assessed the ability of RASB to protect renal function and reduce the development of proteinuria [24–26], with RASB becoming a first line treatment for IgAN [4,10,15,27]. Fewer studies have assessed the effects of RASB in patients with IgAN and persistent hematuria, but without proteinuria, perhaps because disease progression is slower in these patients. In addition, few IgAN patients with hematuria but without proteinuria undergo renal biopsy. A study on the clinicopathological features and outcomes of IgAN patients with proteinuria <1 g/d found that only 23.1% of these patients did not have proteinuria [28]. Although several randomized controlled trials (RCT) and reviews have assessed the effects of RASB on IgAN patients, most of these excluded patients without proteinuria. For example, an RCT assessing the effects of ACEI on renal survival in patients with IgAN enrolled only patients with urinary protein excretion ≥0.5 g/d [5], and another RCT on the effects of ACEI in young patients included only patients with moderate proteinuria [7]. Moreover, the KDIGO guidelines did not include recommendations for RASB in patients without proteinuria. A study evaluating the associations between RASB therapy and ESRD in patients stratified by levels of proteinuria, including individuals without proteinuria, found that RASB had renal protective effects in subjects with urinary protein excretion >1 g/d, but not in patients with urinary protein excretion <1 g/d [15]. This result did not necessarily indicate that RASB is ineffective for patients with proteinuria <1 g/d or those with hematuria alone, because the incidence of ESRD was rare in these subgroups.

Generally, kidney biopsies are rarely performed in patients with hematuria but without proteinuria. However, persistent hematuria in significant amounts has been found to independently increase the risk of renal function loss in IgAN. Moreover, some physicians believe it necessary to biopsy patients with persistent hematuria to rule out the possibility of IgAN, especially in women of childbearing age. For these reasons, renal biopsies were obtained from the individuals enrolled in the present study.

Specific treatment is generally not recommended for IgAN patients without proteinuria, with annual follow-up regarded as sufficient [16,29]. However, some of these patients may develop proteinuria as the disease progresses. For example, of the 110 patients in the present study, 38 (34.5%) developed proteinuria during follow up, including 30 patients who did not receive RASB treatment.

Several recent studies have sought to identify parameters prognostic of long-term outcomes in patients with IgAN, including initial renal function, hypertension, and significant proteinuria and hematuria [17,30–32]. Renal lesions are also associated with renal outcomes [33,34]. According to the latest Oxford classification of IgAN, mesangial hypercellularity (M), segmental sclerosis (S), and interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy (T) are predictive of renal outcomes. Endocapillary cellularity (E) is also predictive in the absence of immunosuppressive therapy. This study added crescents (C) to the Oxford classification MEST score [35]. These parameters have also been shown to predict progression to ESRD in patients with IgAN. Both clinical variables and renal histopathology, including eGFR, proteinuria and Oxford classification score, have been identified as risk factors for ESRD in patients with IgAN [36]; and hypertension, proteinuria and the degree of renal lesions were found to be independent predictors for predicting the risk of death/dialysis in patients with IgAN [37].

Proteinuria has been regarded as a risk factor for renal damage, with remission of proteinuria improving the prognosis of patients with IgAN, regardless of initial proteinuria levels [38]. Similarly, persistent hematuria in significant amounts increased renal function loss, with remission of hematuria having a favorable effect on progression of IgAN [17]. Rational treatment should be designed for IgAN patients with persistent hematuria but without proteinuria [38]. Early changes in proteinuria were demonstrated to be a surrogate end point for clinical progression of IgAN in selected settings [39]. Thus, in assessing the benefits of RASB, the present study selected the appearance of proteinuria as the primary outcome, finding that RASB reduced the risk of the primary outcome as well as reducing the level of hematuria to a greater extent than the lack of treatment, and indicating that RASB had a significant effect on the remission of hematuria. Taken together, these findings suggest that RASB can benefit IgAN patients with persistent hematuria alone.

RASB treatment, however, did not affect the rate of eGFR decline in all patients and in patients without hypertension. Consistent with our result, an earlier retrospective study assessing the effect of corticosteroids (CS) on IgAN measured the slope of eGFR as a renal outcome [40]. Subgroup analysis showed that the rate of eGFR decline was slow in patients with proteinuria <1 g/d, with no significant difference between patients who were and were not treated with CS. A study of IgAN patients with minimal proteinuria and/or with hematuria alone found that only 23.1% had hematuria alone and only 2.9% developed injured renal function [28]. Another study on the outcomes in IgAN patients with minimal or no proteinuria found that only 3.5% showed a >50% increase in SCr and none developed ESRD [41], indicating that progression is slow in IgAN patients with low levels of proteinuria. Future studies assessing the effect of RASB on the decline in eGFR rate among IgAN patients with persistent hematuria alone should include a longer follow-up time. Because of the important roles of proteinuria and hematuria levels in predicting renal progression, RASB should be regarded as beneficial for IgAN patients with persistent hematuria alone.

RASB has been shown to control blood pressure and reduce proteinuria. We found that, after excluding patients with hypertension, RASB was effective in preventing the primary outcome and lowering hematuria, with blood pressure similar in the two groups. These findings indicated that hypertension was not a prerequisite for RASB treatment in IgAN patients with hematuria alone, and that low-dose RASB did not significantly affect blood pressure in patients without hypertension.

This study had several limitations. The first was its retrospective design, suggesting that there may have been unmeasured potential confounders. In addition, the limited follow-up time precluded a determination of the association between RASB and the rate of eGFR decline. Large multicenter studies and longer follow-up time are needed to assess the effect of RASB on the rate of eGFR decline.

Conclusions

RASB independently reduced the risk of proteinuria development and increased the remission of hematuria in IgAN patients with hematuria alone, indicating that RASB could be beneficial in their treatment. This benefit was applicable to patients without hypertension, and RASB did not significantly affect their blood pressure.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the matched IgAN patients only with hematuria initially (n=103).

| Characteristics at biopsy | Treatment group (n=37) | Untreated group (n=66) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Male (%) | 10 (27.0) | 17 (25.8) | 0.89 |

| Age (years) | 31±12 | 29±10 | 0.29 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 72.0 (59.0–86.5) | 71.0 (58.8–77.5) | 0.26 |

| Initial eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 102.2±23.7 | 107.9±25.2 | 0.26 |

| Hematuria, (cells/hpf) | 37.0 (27.0–71.0) | 33.0 (13.0–68.0) | 0.14 |

| Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 120 (108–128) | 118 (104–124) | 0.53 |

| Diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 76 (70–84) | 71 (65–80) | 0.18 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 5 (13.5) | 5 (7.6) | 0.49 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 127 (116–131) | 127 (117–134) | 0.69 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 42.1±4.6 | 42.1±4.4 | 0.96 |

| Uric acid (μmol/L) | 288 (227–339) | 283 (255–309) | 0.67 |

| Low hemoglobin, n (%) | 4 (10.8) | 8 (12.1) | 1.00 |

| Hypoalbuminemia, n (%) | 2 (5.4) | 3 (4.5) | 1.00 |

| Hyperuricemia, n (%) | 4 (10.8) | 7 (10.6) | 1.00 |

| Biopsy characteristics | |||

| M1, n (%) | 21 (56.8) | 30 (45.5) | 0.27 |

| E1, n (%) | 7 (18.9) | 16 (24.2) | 0.53 |

| S1, n (%) | 15 (40.5) | 20 (30.3) | 0.29 |

| T1–2, n (%) | 1 (2.7) | 5 (7.6) | 0.42 |

| C1–2, (%)* | 3 (8.1) | 4 (6.1) | 0.70 |

| Duration from initial diagnosis to start of therapy (months) | 5.0 (1.0–21.0) | 5.6 (1.0–12.0) | 0.94 |

Crescents >50% were excluded.

eGFR – estimated glomerular filtration rate; RASB – reninangiotensin system blockers; M – mesangial hypercellularity; E–endocapillary hypercellularity; S – segmental glomerulosclerosis; T – tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis; C – crescent.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Wyatt RJ, Julian BA. IgA nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2402–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1206793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coppo R. Treatment of IgA nephropathy: Recent advances and prospects. Nephrol Ther. 2018;14(Suppl 1):S13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.nephro.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lv J, Xu D, Perkovic V, et al. TESTING Study Group. Corticosteroid therapy in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1108–16. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011111112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radhakrishnan J, Cattran DC. The KDIGO practice guideline on glomerulonephritis: Reading between the (guide)lines – application to the individual patient. Kidney Int. 2012;82:840–56. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Praga M, Gutierrez E, Gonzalez E, et al. Treatment of IgA nephropathy with ACE inhibitors: A randomized and controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1578–83. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000068460.37369.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woo KT, Lau YK, Zhao Y, et al. Disease progression, response to ACEI/ATRA therapy and influence of ACE gene in IgA nephritis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2007;4:227–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coppo R, Peruzzi L, Amore A, et al. IgACE: A placebo-controlled, randomized trial of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in children and young people with IgA nephropathy and moderate proteinuria. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1880–88. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006040347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng J, Zhang W, Zhang XH, et al. ACEI/ARB therapy for IgA nephropathy: A meta analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:880–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang F, Liu H, Liu D, et al. Effects of RAAS inhibitors in patients with kidney disease. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017;19:72. doi: 10.1007/s11906-017-0771-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ji Y, Yang K, Xiao B, et al. Efficacy and safety of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blocker therapy for IgA nephropathy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:3689–95. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erkan E. Proteinuria and progression of glomerular diseases. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28:1049–58. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borrego J, Mazuecos A, Gentil MA, et al. Proteinuria as a predictive factor in the evolution of kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:3627–29. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu X, Li H, Liu Y, et al. Tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis scores of Oxford classification combinded with proteinuria level at biopsy provides earlier risk prediction in lgA nephropathy. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1100. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01223-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu JR, Coresh J. The public health dimension of chronic kidney disease: What we have learnt over the past decade. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:ii113–20. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka S, Ninomiya T, Katafuchi R, et al. The effect of renin-angiotensin system blockade on the incidence of end-stage renal disease in IgA nephropathy. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2016;20:689–98. doi: 10.1007/s10157-015-1195-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barratt J, Feehally J. Treatment of IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1934–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sevillano AM, Gutierrez E, Yuste C, et al. Remission of hematuria improves renal survival in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3089–99. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017010108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He W, Liu Y, Feng J, et al. The epidemiological characteristics of stroke in Hunan Province, China. Front Neurol. 2018;9:583. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gatta A, Verardo A, Bolognesi M. Hypoalbuminemia. Intern Emerg Med. 2012;7(Suppl 3):S193–99. doi: 10.1007/s11739-012-0802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng C, Wang YL, Wei J, et al. Association between low serum magnesium concentration and hyperuricemia. Magnes Res. 2015;28:56–63. doi: 10.1684/mrh.2015.0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Working Group of the International IgA Nephropathy Network and the Renal Pathology Society. Cattran DC, Coppo R, Cook HT, et al. The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: Rationale, clinicopathological correlations, and classification. Kidney Int. 2009;76:534–45. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barbour S, Feehally J. An update on the treatment of IgA nephropathy. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2017;26:319–26. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunz R, Friedrich C, Wolbers M, Mann JFE. Meta-analysis: Effect of monotherapy and combination therapy with inhibitors of the renin angiotensin system on proteinuria in renal disease. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:30–48. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-1-200801010-00190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tobe SW, Clase CM, Gao P, et al. ONTARGET and TRANSCEND Investigators. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both in people at high renal risk: Results from the ONTARGET and TRANSCEND studies. Circulation. 2011;123:1098–107. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.964171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mann JF, Schmieder RE, McQueen M, et al. ONTARGET Investigators. Renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both, in people at high vascular risk (the ONTARGET study): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:547–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61236-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid S, Cawthon PM, Craig JC, et al. Non-immunosuppressive treatment for IgA nephropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(16):CD003962. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003962.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan M, Li W, Zou G, et al. Clinicopathological features and outcomes of IgA nephropathy with hematuria and/or minimal proteinuria. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2015;40:200–6. doi: 10.1159/000368495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pozzi C. Treatment of IgA nephropathy. J Nephrol. 2016;29:21–25. doi: 10.1007/s40620-015-0248-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Amico G. Natural history of idiopathic IgA nephropathy: Role of clinical and histological prognostic factors. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:227–37. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2000.8966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bartosik LP, Lajoie G, Sugar L, Cattran DC. Predicting progression in IgA nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:728–35. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.27689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coppo R, D’Amico G. Factors predicting progression of IgA nephropathies. J Nephrol. 2005;18:503–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Working Group of the International IgA Nephropathy Network and the Renal Pathology Society. Roberts IS, Cook HT, Troyanov S, et al. The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: Pathology definitions, correlations, and reproducibility. Kidney Int. 2009;76:546–56. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Working Group of the International IgA Nephropathy Network and the Renal Pathology Society. Coppo R, Troyanov S, Camilla R, et al. The Oxford IgA nephropathy clinicopathological classification is valid for children as well as adults. Kidney Int. 2010;77:921–27. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trimarchi H, Barratt J, Cattran DC, et al. Working Group of the International IgA Nephropathy Network and the Renal Pathology Society, Conference Participants. Oxford Classification of IgA nephropathy 2016: An update from the IgA Nephropathy Classification Working Group. Kidney Int. 2017;91:1014–21. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka S, Ninomiya T, Katafuchi R, et al. Development and validation of a prediction rule using the Oxford classification in IgA nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:2082–90. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03480413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berthoux F, Mohey H, Laurent B, et al. Predicting the risk for dialysis or death in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:752–61. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010040355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reich HN, Troyanov S, Scholey JW, Cattran DC Toronto Glomerulonephritis Registry. Remission of proteinuria improves prognosis in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:3177–83. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007050526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inker LA, Mondal H, Greene T, et al. Early change in urine protein as a surrogate end point in studies of IgA nephropathy: An individual-patient meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68:392–401. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tesar V, Troyanov S, Bellur S, et al. VALIGA study of the ERA-EDTA Immunonephrology Working Group. Corticosteroids in IgA nephropathy: A retrospective analysis from the VALIGA study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:2248–58. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014070697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gutierrez E, Zamora I, Ballarin JA, et al. Grupo de Estudio de Enfermedades Glomerulares de la Sociedad Española de Nefrología (GLOSEN) Long-term outcomes of IgA nephropathy presenting with minimal or no proteinuria. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1753–60. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012010063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the matched IgAN patients only with hematuria initially (n=103).

| Characteristics at biopsy | Treatment group (n=37) | Untreated group (n=66) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Male (%) | 10 (27.0) | 17 (25.8) | 0.89 |

| Age (years) | 31±12 | 29±10 | 0.29 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 72.0 (59.0–86.5) | 71.0 (58.8–77.5) | 0.26 |

| Initial eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 102.2±23.7 | 107.9±25.2 | 0.26 |

| Hematuria, (cells/hpf) | 37.0 (27.0–71.0) | 33.0 (13.0–68.0) | 0.14 |

| Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 120 (108–128) | 118 (104–124) | 0.53 |

| Diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 76 (70–84) | 71 (65–80) | 0.18 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 5 (13.5) | 5 (7.6) | 0.49 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 127 (116–131) | 127 (117–134) | 0.69 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 42.1±4.6 | 42.1±4.4 | 0.96 |

| Uric acid (μmol/L) | 288 (227–339) | 283 (255–309) | 0.67 |

| Low hemoglobin, n (%) | 4 (10.8) | 8 (12.1) | 1.00 |

| Hypoalbuminemia, n (%) | 2 (5.4) | 3 (4.5) | 1.00 |

| Hyperuricemia, n (%) | 4 (10.8) | 7 (10.6) | 1.00 |

| Biopsy characteristics | |||

| M1, n (%) | 21 (56.8) | 30 (45.5) | 0.27 |

| E1, n (%) | 7 (18.9) | 16 (24.2) | 0.53 |

| S1, n (%) | 15 (40.5) | 20 (30.3) | 0.29 |

| T1–2, n (%) | 1 (2.7) | 5 (7.6) | 0.42 |

| C1–2, (%)* | 3 (8.1) | 4 (6.1) | 0.70 |

| Duration from initial diagnosis to start of therapy (months) | 5.0 (1.0–21.0) | 5.6 (1.0–12.0) | 0.94 |

Crescents >50% were excluded.

eGFR – estimated glomerular filtration rate; RASB – reninangiotensin system blockers; M – mesangial hypercellularity; E–endocapillary hypercellularity; S – segmental glomerulosclerosis; T – tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis; C – crescent.