Abstract

Although personal identity development has been conceptualized as a source of psychological stability and protective against depressive symptoms among Hispanic immigrants, there remains ambiguity regarding the directional relationship between identity development and depression. To address this limitation, the current study sought to establish directionality between identity development and depressive symptoms. The sample consisted of 302 recent (<5 years) immigrant Hispanic adolescents (53.3% boys; Mage = 14.51 years at baseline; SD = 0.88 years) from Miami and Los Angeles who participated in a longitudinal study. The findings suggested a bidirectional relationship between identity and depressive symptoms such that identity coherence negatively predicted depressive symptoms, yet depressive symptoms also negatively predicted coherence and positively predicted subsequent identity confusion. Findings not only provide further evidence for the protective role of identity development during times of acute cultural transitions, but also emphasize the need for research to examine how depressive symptoms, and psychopathology more broadly, may interfere with establishing a sense of self.

Keywords: Personal identity, Depressive symptoms, Adolescents, Hispanic immigrants

Introduction

Hispanic youth face numerous challenges that place them at risk for mental health problems (Asfour et al. 2017). Compared to non-Hispanic Whites, Hispanics are more likely to experience depressive symptoms (Kann et al. 2018; Limon et al. 2016). Given these disparities and the fact that Hispanic youth represent a large and growing proportion of the U.S. population (Stepler and Lopez 2016), there is a need to understand factors associated with mental health and well-being among this population. Although cultural processes can play an important role, it is also necessary to focus on other factors that contribute to these mental health problems (Causadias et al. 2018). One such factor is identity development, an integral process that begins to unfold during adolescence and anchors youth within a given set of social roles (Côté and Levine 2015).

Identity development helps young people establish themselves within a set of social roles, thereby protecting them against aimlessness associated with depression (Crocetti et al. 2008). A coherent sense of identity has been associated with higher self-esteem and lower internalizing symptoms (for a review, see Crocetti et al. 2014). At the same time, depressive symptoms may also hinder identity development (Marcia 2006). Because identity development requires youth to constantly develop, evaluate, and revise their identity (Crocetti et al. 2008; Schwartz et al. 2005), problems with motivation, decision-making, and engagement which are common among individuals with depression (American Psychiatric Association 2013) may pose barriers to identity development (Klimstra and Denissen 2017). Consistently, depressive symptoms predict weaker identity commitments over time in adolescence (Schwartz et al. 2012). As a result, the directionality of the relationship between identity development and depression remains unclear (Klimstra and Denissen 2017). To address these gaps, the current study examined the directional links between general identity development and depressive symptoms among recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents.

Conceptualizing Identity Development

According to Erikson (1950), identity develops in a dynamic manner involving coherence and confusion, wherein healthy identity development results from a preponderance of coherence over confusion. Coherence refers to a sense of certainty, comfort, and satisfaction with one’s sense of who one is and where one is going in life. Confusion, conversely, signifies a sense of uncertainty marked by an inability to enact and maintain lasting commitments and a lack of a clear sense of purpose and direction. In this sense, identity confusion is viewed as a destabilization in one’s sense of self that undermines one’s sense of consistency across time and place (Erikson 1968). Although these two dimensions are negatively correlated, they are not opposites on a single continuum (Schwartz et al. 2009). Individuals may not only exhibit coherence in some identity domains and confusion in others, but may also, within a single identity domain, express coherence in some respects and confusion in others. For example, an adolescent may express certainty regarding going to college (i.e., coherence) yet express doubts regarding whether they can manage being away from home or the workload associated with higher education (i.e., confusion).

Identity coherence and confusion not only operate somewhat independently but are also differentially related to adolescent outcomes (Meca et al. 2017; Syed et al. 2013). Broadly, identity coherence is expected to facilitate positive adjustment and to protect against depression, whereas identity confusion is expected to interfere with positive development and predispose individuals to depression (Schwartz et al. 2009). Several cross-sectional studies have found identity confusion to be positively associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety, and coherence to be negatively associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety (e.g., Luyckx et al. 2013; Schwartz et al. 2009). Despite this large body of work, the directionality of the links between identity and psychopathology remains unclear (Klimstra and Denissen 2017). The establishment of directionality represents an important first step toward determining strategic points of intervention (Maxwell and Cole 2007). For example, if identity development predicts depressive symptoms, an effective avenue for intervention may be promoting positive identity development as a way of preventing depressive symptoms. On the other hand, if depressive symptoms predict identity development, interventions may need to target depressive symptoms as a way of promoting identity development. If the relationship is bidirectional, both types of strategies would be needed.

To date, only three studies have sought to identify the directionality in the relationship between identity processes and depressive symptoms (i.e., Becht et al. 2019; Schwartz et al. 2012; van Doeselaar et al. 2018). Schwartz et al. (2012) found a bidirectional negative relationship between identity coherence, as determined by the strength of adolescents’ commitment to educational and interpersonal goals, and internalizing symptoms (e.g., anxiety and depression) among early to middle Dutch adolescents. In contrast, van Doeselaar et al. (2018) found that identity commitment negatively predicted depressive symptoms, but that depressive symptoms did not predict identity commitments, among Dutch youth. Lastly, Becht and colleagues (2019) found that identity confusion, not identity coherence, positively predicted depressive symptoms, and that depressive symptoms did not predict subsequent identity coherence or confusion, among a sample of Dutch and Belgian youth. It is worth noting that these studies used primarily White samples which decreases the external validity of the findings. Becht et al. (2019 p. 8), speculated that, for ethnic minorities, “failing to establish strong identity commitments and experiencing ongoing identity uncertainty may be more strongly related to subsequent depressive symptoms.” As such, it is difficult to understand how well findings from these prior studies generalize to recently immigrated Hispanic youth in a U.S. cultural context, whose identity development may be more complex and difficult compared with ethnic majority youth (Azmitia et al. 2008).

Identity Development in Hispanic Immigrant Adolescents

In addition to focusing on more general identity domains such as career, relationships, and values, Hispanic youth must also make sense of themselves culturally (e.g., deciding what it means to be Hispanic and how their ethnic group fits into the larger national context) (Meca et al. 2017; Syed and Juang 2014). For this reason, achieving identity coherence and minimizing identity confusion may be more difficult for immigrant and minority adolescents because of the greater amount of identity work required of them as compared to majority-group adolescents (Schwartz et al. 2017). At the same time, establishing a coherent sense of self and identity is of great importance to adolescents from immigrant backgrounds as it serves to anchor them during times of acute cultural change (Schwartz et al. 2006). Consistently, previous longitudinal work (Meca et al. 2017; Schwartz et al. 2017) with Hispanic adolescents have found that identity confusion, not identity coherence, positively predicts internalizing symptoms (e.g., anxiety and depression). Despite utilizing longitudinal designs to determine the effects of identity coherence and confusion on depressive symptoms among Hispanic youth, these prior studies solely tested unidirectional effects (identity → depressive symptoms) and did not examine effects in the opposite direction. Indeed, the directional relationship between identity development and depression among Hispanic youth has yet to be examined and understood.

The Current Study

To address the previously stated gaps in the literature, the aim of the current study was to establish the directional relationship between identity processes and depressive symptoms utilizing a broad, general measure of identity coherence and confusion among a sample of recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents. The current study focuses on recent Hispanic immigrant adolescents for two reasons. First, as previously noted, identity development has been conceptualized as a source of stability for adolescents during times of acute cultural change, where such cultural change can compromise youth’s mental health during this transition (Schwartz et al. 2006). Additionally, recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents are likely to experience discrimination and other cultural stressors, which may exacerbate difficulties with identity development (Rumbaut 2008). In sum, the experience of immigration, coupled with experiences of discrimination, may create a context that complicates the process of identity development for many Hispanic immigrant youth (Meca et al. 2017).

Two hypotheses regarding the directional relationships between identity development and depressive symptoms among recently immigrated Hispanic youth were proposed. First, given the role of identity development during acute cultural change, and findings from prior studies (e.g., Becht et al. 2019; van Doeselaar et al. 2018), it was hypothesized that the effect would be largely unidirectional, such that depressive symptoms would not predict identity coherence or confusion. Second, and consistent with prior longitudinal studies (Meca et al. 2017; Schwartz et al. 2017), it was hypothesized that identity confusion—and not identity coherence—would positively predict depressive symptoms over time.

Methods

Participants

The sample for the present analyses was drawn from Construyendo Oportunidades Para Adolescentes Latinos (COPAL; Schwartz et al. 2014), a six-wave longitudinal study on acculturation, identity, family functioning, and health among recent Hispanic immigrant families. To be eligible for this study, youth had to have (a) arrived in the US within 5 years of the baseline assessment and (b) be either entering or finishing the 9th grade. The sample consisted of 302 Hispanic adolescents from immigrant families in Miami (n = 152) and Los Angeles (n = 150). On average, participants were 14.51 years old at baseline (SD = 0.88, range 14–17) and 46.7% were female. Although 32% of the sample did not report annual household income at baseline, for those participants who responded to this question, the mean annual household income was $27,028 (SD = $13,454) in Miami and $34,521 (SD = $5398) in Los Angeles. Whereas the Miami sample was primarily from Cuba (61%), the Dominican Republic (8%), Nicaragua (7%), Honduras (6%), Colombia (6%), and other Hispanic countries (12%), the Los Angeles sample was primarily from Mexico (70%), El Salvador (9%), Guatemala (6%), and other Hispanic countries (15%).

Procedure

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Miami and the University of Southern California, and by the Research Review Committees at each of the respective participating school districts. Additional study details are reported in Schwartz et al. (2014). Participants were recruited between May and November 2010 from 23 randomly selected public high schools in Miami and Los Angeles with student bodies that were at least 75% Hispanic. Baseline data were gathered during the summer and fall of 2010, and subsequent time points occurred every six months thereafter over a three-year time period, for a total of 6 time points corresponding to baseline and 6, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months post-baseline. The current analyses used adolescent data from the first (baseline), third (12-month post-baseline), and fifth (24-month post-baseline) time points to examine the associations between study variables across full-year increments.

Parent-adolescent dyads completed the assessment at the same time, in separate rooms, and in the language of their choice (i.e., English or Spanish) using an audio computer assisted self-interviewing (A-CASI) methodology. All measures were translated into Spanish using a two-step translation process (Sireci et al. 2006) in which measures were translated by one translator from English to Spanish, back-translated by a second translator (from Spanish to English), and then evaluated by both translators to resolve discrepancies. Although 84% of adolescents completed their baseline assessments in Spanish, this percentage decreased to 69.5% by Time 5. Parents received $40 at baseline, with increments of $5 at each subsequent time point, and adolescents were compensated for their participation with movie tickets at each time point. Intensive tracking strategies were utilized to maximize participant retention (Knight et al. 2009). Overall, 85% of participants were retained through all waves. Little’s (1988) Missing Completely at Random test indicated that data were missing at random [χ2(20) = 27.520, p = 0.121], indicating that results were not biased as a result of missing values.

Measures

Identity coherence and confusion

Identity coherence and confusion were assessed using the 12-item identity subscale from the Erikson Psychosocial Stage Inventory (EPSI; Rosenthal et al. 1981). Six items are worded in a ‘positive’ direction towards coherence (α = 0.80; Sample item: “I know what kind of person I am”), and 6 items are worded in a ‘negative’ direction towards confusion (α = 0.73; Sample item: “I don’t really know who I am”). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Strongly Disagree) to 4 (Strongly Agree). Prior analyses have supported the two-factor structure, even after controlling for potential methodological effects of item wording (Schwartz et al. 2009). Indeed, in the current study, coherence and confusion were found to be only moderately related to each other across time points (r = −0.334 to −0.221).

Depressive symptoms

The 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977) assessed adolescents’ depressive symptoms (α = 0.93, sample item: “I felt sad this week”). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Strongly Disagree) to 4 (Strongly Agree) and ask participants how depressed they have felt during the week prior to assessment. The CES-D has been translated into Spanish and used frequently with Hispanic individuals (e.g., Todorova et al. 2010).

Analytic Strategy

Analyses were conducted in Mplus v8.0 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2017). Missing data were handled using full-information maximum likelihood estimation. Model fit was evaluated using the comparative fit index (CFI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). According to values suggested by Little (2013), good fit is defined as CFI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤ 0.05, and SRMR ≤ 0.05; adequate fit is defined as CFI ≥ 0.90, RMSEA ≤ 0.08, and SRMR ≤ 0.08; and mediocre fit is defined as CFI ≥ 0.85, RMSEA ≤ 0.10, and SRMR ≤ 0.10. Although the χ2 value is reported, it was not used to gauge model fit because it tests the null hypothesis of perfect fit, which is rarely plausible with large samples or complex models (Davey and Savla 2010).

As detailed below, the analyses proceeded in four steps. No additional steps or analysis were conducted beyond the ones detailed below. First, longitudinal invariance analyses were conducted to ensure that the study constructs were equivalent across time. Establishing longitudinal invariance is a necessary step prior to any longitudinal analysis, as one must ensure that longitudinal change in a construct is a result of true change in the same construct over time (rather than the latent construct measuring something different at each time point; Little 2013). As such, configural (i.e., the number of factors and the patterning of items onto their respective subscales is consistent across time), metric (i.e., factor loadings between items and subscales are equal across time), and scalar (i.e., item intercepts are equivalent across time) invariance were established prior to conducting substantive longitudinal analyses. Model comparisons were done utilizing the CFI (ΔCFI < 0.010) and RMSEA (ΔRMSEA < 0.010; Little 2013). Although the χ2 difference test is reported, because it tests the null hypothesis that two paths or models are exactly equivalent (Meade et al. 2008), it was not utilized in determining model fit. As such, the assumption of longitudinal metric and scalar invariance would be satisfied if ΔCFI < 0.01 and ΔRMSEA < 0.01. For both metric and scalar invariance, it is possible to reach a conclusion of partial invariance (Brown 2015). Partial invariance indicates that a majority, but not all, of the loadings or intercepts are equivalent across time. A conclusion of partial invariance can also be reached if the overall invariance test indicates a significant difference in fit between models, but no one loading or intercept is found to be responsible for the difference in fit.

Second, descriptive statistics and a correlation matrix were calculated for all study variables. Third, to establish the directional relationship between identity processes (i.e., coherence and confusion) and depressive symptoms, a random intercept cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM; Hamaker et al. 2015) was estimated with gender, age, and years in the United States included as controls. A RI-CLPM is like traditional CLPM, except it utilizes random intercepts to disentangle between-person processes (or trait-like differences) from within-person processes (see Hamaker et al. 2015 for more details). Within-person processes in a RI-CLPM represent fluctuations from measurement wave to measurement wave around individuals’ expected scores, which are based on the individual’s personal mean across timepoints and on the stable between-person component (i.e., the random intercept). As such, cross-lagged effects within a RI-CLPM can be interpreted as the extent to which one’s deviation from one’s expected score on a given variable is related to one’s deviation from their expected score on another variable at the subsequent measurement wave (Hamaker et al. 2015).

Fourth, to temporal invariance or non-varying cross-lagged paths across time (Allison 1990), stationarity (equality) constraints on corresponding cross-lagged relationships were imposed in the final model. If the assumption of stationarity holds, then only one set of lagged path estimates is produced between Time t and Time t + 1. To evaluate the tenability of these stationarity constraints, models with and without these constraints were compared using the ΔCFI (>0.010) and ΔRMSEA (>0.010) criteria to determine whether the stationarity assumption should be statistically retained or rejected.

Results

Establishing Longitudinal Invariance

Results of the longitudinal invariance tests are provided in Table 1. For identity coherence and identity confusion, the configural invariance model was associated with good-to-adequate fit, χ2 (534) = 743.702, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.923; RMSEA = 0.036; SRMR = 0.056. Metric invariance was then examined by constraining factor loadings to be equal across time and comparing this model against the configural invariance model. There was some evidence of metric non-invariance, ΔCFI = 0.014; ΔRMSEA = 0.002. As such, the next step was to identify which factor loading(s) violated the assumption of metric invariance. Following recommendations by Cheung and Rensvold (1999), model comparisons began with the least restrictive model and proceeded by constraining one factor loading at a time, examining the change in the ΔCFI (>0.010) and ΔRMSEA (>0.010) criteria (Little 2013). Results indicated that none of the individual factor loadings were considered nonequivalent, providing evidence for partial metric invariance. Similarly, there was some evidence of scalar non-invariance, ΔCFI = 0.026; ΔRMSEA = 0.005. However, no single intercept met criteria for non-invariance, resulting in partial scalar invariance.

Table 1.

Model fit and comparison for longitudinal invariance models

| Model | χ2(df) | Δχ2 (Δdf) | CFI | ΔCFI | RMSEA | ΔRMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPSI | |||||||

| Configural | 743.702 (534)* | 0.923 | 0.036 | 0.056 | |||

| Metric | 808.160 (558)* | 64.568 (24)* | 0.909 | 0.014 | 0.038 | 0.002 | 0.080 |

| Scalar | 901.727 (582)* | 93.567 (24)* | 0.883 | 0.026 | 0.043 | 0.005 | 0.080 |

| CES-D | |||||||

| Configural | 2482.525 (1587)* | 0.892 | 0.043 | 0.065 | |||

| Metric | 2535.222 (1627)* | 52.697 (40)* | 0.890 | 0.002 | 0.043 | <0.001 | 0.067 |

| Scalar | 2592.398 (1667)* | 57.176 (40)* | 0.888 | 0.002 | 0.043 | <0.001 | 0.067 |

The configural invariance model for the CES-D was associated with good-to-mediocre fit [χ2 (1587) = 2482.525, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.892; RMSEA = 0.043; SRMR = 0.065]. Metric invariance was then examined by constraining factor loadings to equality across time and comparing this model with the configural invariance model. The assumption of metric invariance was satisfied [Δχ2 (40) = 52.697, p < 0.001; ΔCFI = 0.002; ΔRMSEA < 0.001]. Similarly, the assumption of scalar invariance was supported [Δχ2 (40) = 57.176, p < 0.001; ΔCFI = 0.002; ΔRMSEA < 0.001].

Establishing Directional Effects

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. The RI-CLPM model provided an adequate fit to the data, χ2(12) = 39.833, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.945; RMSEA = 0.088. Building on the RI-CLPM model, temporal invariance (stationarity) constraints were imposed on the cross-lagged relationships of identity coherence and confusion with depressive symptoms. The model with temporal invariance constraints was associated with significantly better fit, Δχ2(15) = 14.624, p = 0.479; ΔCFI = 0.017; ΔRMSEA = 0.039. Given this evidence of stationarity, cross-lagged path coefficients were collapsed across corresponding time points and examined as one set of lagged estimates between Times t and t + 1.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for identity coherence, identity confusion, and depression symptoms at each study wave

| Variable | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|

| Identity coherence (T1) | 3.152 | 0.573 |

| Identity coherence (T3) | 2.976 | 0.704 |

| Identity coherence (T5) | 2.981 | 0.775 |

| Identity confusion (T1) | 1.553 | 0.756 |

| Identity confusion (T3) | 1.520 | 0.787 |

| Identity confusion (T5) | 1.518 | 0.873 |

| Depressive symptoms (T1) | 1.489 | 0.796 |

| Depressive symptoms (T3) | 1.479 | 0.747 |

| Depressive symptoms (T5) | 1.438 | 0.778 |

Table 3.

Bivariate zero-order correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Identity coherence (T1) | - | ||||||||

| 2. Identity coherence (T3) | 0.399*** | - | |||||||

| 3. Identity coherence (T5) | 0.333** | 0.395*** | - | ||||||

| 4. Identity confusion (T1) | −0.334*** | −0.209* | −0.166* | - | |||||

| 5. Identity confusion (T3) | −0.122 | −0.301* | −0.138* | 0.349*** | - | ||||

| 6. Identity confusion (T5) | −0.069 | −0.325** | −0.221* | 0.312*** | 0.337*** | - | |||

| 7. Depressive symptoms (T1) | −0.217** | −0.231* | −0.151*** | 0.524*** | 0.380*** | 0.229*** | - | ||

| 8. Depressive symptoms (T3) | −0.135 | −0.363*** | −0.230*** | 0.296*** | 0.489*** | 0.369*** | 0.429*** | - | |

| 9. Depressive symptoms (T5) | −0.096 | −0.287*** | −0.292*** | 0.217*** | 0.282*** | 0.548*** | 0.300*** | 0.506*** | - |

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

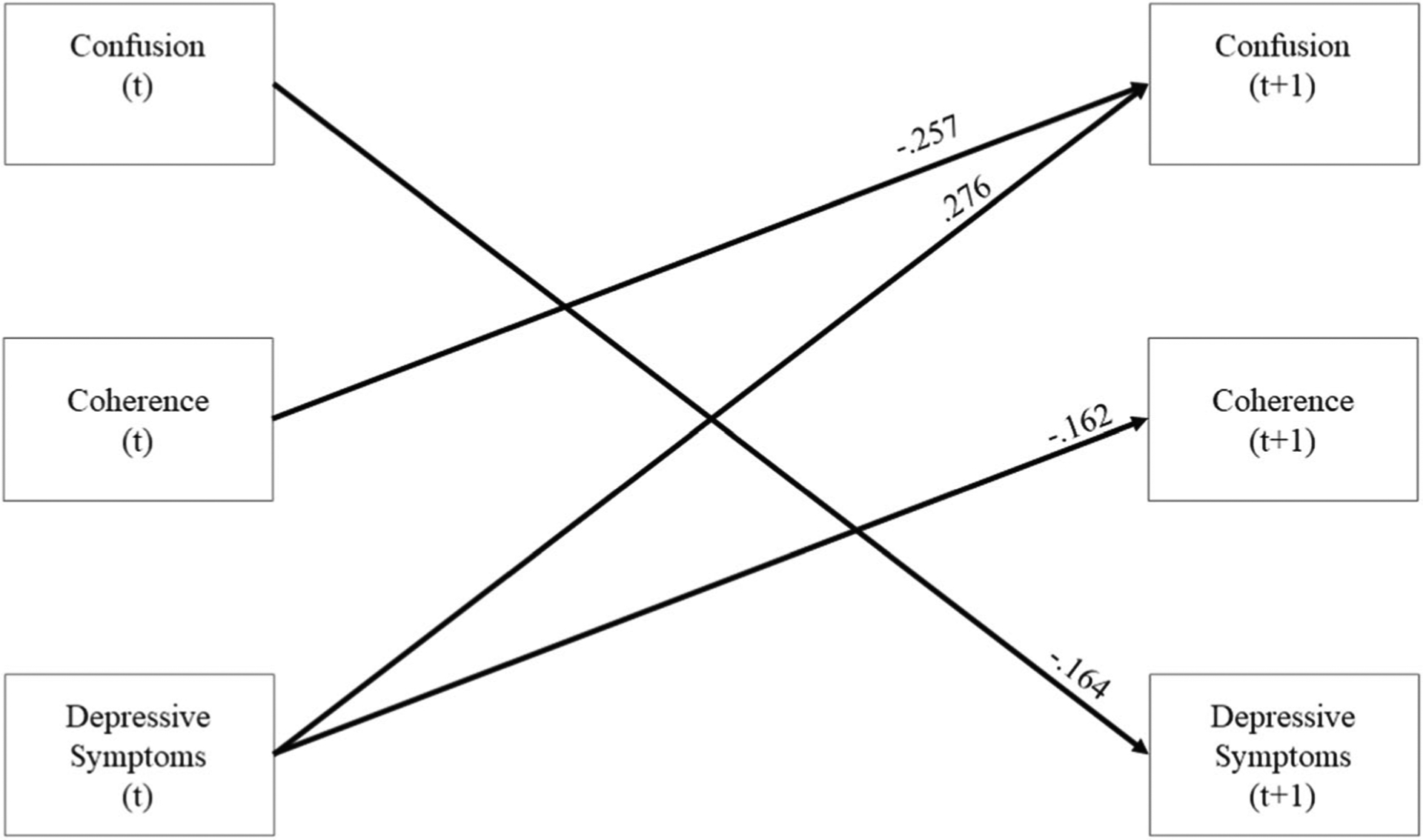

As shown in Table 4 and Fig. 1, results indicated that identity coherence at Time t negatively predicted depressive symptoms at Time t + 1 (β = −0.164, p < 0.001, 95%CI = −0.249 to −0.080). In other words, individuals experiencing greater than their within-person average identity coherence at one wave were more likely to experience lower than their within-person average levels of depressive symptoms at the next wave. At the same time, depressive symptoms at Time t positively predicted identity confusion (β = 0.276, p = 0.001, 95%CI = 0.107–0.444) and negatively predicted identity coherence (β = −0.162, p = 0.044, 95%CI = −0.319 to −0.004) at Time t + 1. In addition, results indicated a unidirectional relationship between identity coherence and confusion. Specifically, identity coherence at Time t negatively predicted identity confusion at Time t + 1 (β = −0.257, p = 0.005, 95%CI = −0.436 to −0.078). Above these directional effects, results also indicated a large between-person correlation between identity confusion and depressive symptoms (r = 0.718, p < 0.001, 95%CI = 0.438–0.998). This finding suggests between-person stability such that Hispanic immigrant youth with higher identity confusion tended to experience greater depressive symptoms across time, and vice versa.

Table 4.

Cross-lagged paths for temporal invariance model

| Outcome (t + 1) | Predictor (t) | Estimate1 | p-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confusion | Coherence | −0.257 | 0.005 | −0.436, −0.089 |

| Depressive | 0.276 | 0.001 | 0.107, 0.444 | |

| symptoms | ||||

| Coherence | Confusion | −0.017 | 0.760 | −0.126, 0.092 |

| Depressive | −0.162 | 0.044 | −0.319, −0.004 | |

| symptoms | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | Confusion | 0.001 | 0.988 | −0.134, 0.136 |

| Coherence | −0.164 | <0.001 | −0.249, −0.080 |

All estimates are standardized regression coefficient

Fig. 1.

Standardized parameter estimates for the within-person cross-lagged effects of the RI-CLPM are presented above. Given parameter values from Time 1 to Time 3 and Time 3 to Time 5 were identical, as a result of the stationarity constraints imposed in Step 1, for simplicity we present the cross-lagged effects from t to t + 1. We have also excluded autoregressive paths and correlations between the residual estimates and path estimates involving the covariates of gender, age, and number of years in the United States

Discussion

Compared to non-Hispanic Whites, Hispanics are more likely to experience depressive symptoms (Limon et al. 2016). Thus, there is a need to identify and clarify predictors and consequences of mental health problems among Hispanic youth (Silva and Van Orden 2018). In particular, a coherent sense of self may serve to anchor youth during times of acute cultural change (Meca et al. 2017; Schwartz et al. 2006). Despite the apparent importance of identity formation during cultural transitions, to date, the directional relationship between identity development and depression among Hispanic youth has yet to be examined. To address these gaps in the literature, the current study sought to identify directional relationships between identity development (coherence and confusion) with depressive symptoms among recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents.

Consistent with Erikson’s (1968) conceptualization of the role of identity development in psychopathology, and with a wealth of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Luyckx et al. 2013; Meca et al. 2017; Schwartz et al. 2009), identity coherence negatively predicted depressive symptoms at subsequent time points. In contrast, identity confusion did not predict subsequent depressive symptoms. Thus, it appears to be the absence of a coherent sense of self, rather than the presence of confusion, that is associated with subsequent depressive symptoms. Such findings provide further evidence suggesting that a coherent sense of self serves to anchor the individual during times of transition, whether during acute cultural transitions (i.e., acculturation) or, more broadly, the transition into emerging adulthood (Schwartz et al. 2013). Indeed, a coherent sense of identity provides individuals with a sense of structure through which to understand self-relevant information (Adams and Marshall 1996) and thus shapes how individuals negotiate with the social and cultural environment as well as the opportunities they choose to pursue (Côté 2002).

At the same time, results indicated that higher levels of depressive symptoms were prospectively associated with less identity coherence. Given that depressive symptoms include a lack of energy and diminished interest in life (American Psychiatric Association 2013), the capacity to establish a coherent sense of self is likely to be impaired. As emphasized in the identity literature, the development of a coherent sense of self represents an agentic and effortful process consisting of active exploration of potential identity alternatives, evaluation of existing identity commitments, and reconsideration of these existing commitments (Luyckx et al. 2006; Schwartz et al. 2005). Depressive symptoms are likely to interfere with such an agentic process. Depressive symptoms were also positively associated with identity confusion at subsequent time points. Thus, in addition to impairing the formation of a coherent sense of self, depressive symptoms also foster confusion in one’s current sense of self. Given that depression is also associated with impaired decision-making (American Psychiatric Association 2013), it is possible that youth experiencing depressive symptoms are also engaging in maladaptive forms of identity exploration (Luyckx et al. 2008). For example, these youth may engage in ruminative exploration, which is characterized by a repetitive and passive type of identity exploration in which one continuously obsesses over and questions one’s choices. Future research is necessary to explore whether ruminative exploration and other forms of maladaptive identity processes mediate the relationship between depressive symptoms and identity processes.

Although the interplay between coherence and confusion was not a focus of the current study, our findings also have important implications for understanding the dynamic interplay between identity coherence and confusion. Findings from the current study support Erikson’s (1950, 1968) propositions that identity coherence and confusion represent distinct dimensions of identity development (Schwartz et al. 2009). Specifically, identity coherence and confusion were differentially related to depressive symptoms at the within-person level, consistent with past cross-sectional (e.g., Schwartz et al. 2005; Syed et al. 2013) and longitudinal (e.g., Meca et al. 2017; Schwartz et al. 2017) studies indicating differential effects on a variety of adolescent outcomes. Additionally, identity coherence predicted lower subsequent identity confusion, whereas identity confusion did not predict lower subsequent identity coherence. This finding was surprising given past research indicating a significant relationship between confusion and coherence (e.g., Schwartz et al. 2017; Syed et al. 2013). It is possible that, for youth undergoing a cultural transition, the relationship between confusion and coherence may differ from that of youth who do not face such cultural transitions. Some confusion during this time of cultural transition may be normative and necessary for identity development (Schwartz et al. 2006). However, for others, confusion during this cultural transition may serve to impair identity development and the establishment of a coherent sense of self. Future research should further explore the role of identity confusion in predicting subsequent identity coherence.

Implications for Intervention

Given the important disparities in internalizing symptoms between Hispanic and non-Hispanic youth (Kann et al. 2018; Limon et al. 2016), the findings have possible programmatic implications for reducing depression among this population. Indeed, the establishment of directionality sheds light on strategic points of intervention (Maxwell and Cole 2007). Although additional research is needed, the findings point to the possibility that interventions focusing on reducing depressive symptoms should also consider promoting increased identity coherence. As reviewed by Eichas et al. (2014), several interventions have been developed to target identity development specifically. Although the activities utilized to promote identity development vary across programs, they have largely focused on promoting and encouraging active identity exploration through self-construction (i.e., making identity-related choices made from among a variety of identity alternatives) and self-discovery (i.e., discover and actualize the person’s set of unique potentials, talents, skills, and capabilities) (Schwartz et al. 2005). Even though these programs represent an important first step in developing activities to promote the enactment of and adherence to commitments and reduce identity distress (e.g., Eichas et al. 2018; Meca et al. 2014), future work is necessary to establish the efficacy of such interventions. At the same time, the fact that depressive symptoms predicted increased identity confusion and decreased identity coherence suggests that future identity-focused interventions should consider mental health issues, and whether depressive symptoms may weaken the capacity of the program’s ability to effectively encourage identity development.

Limitations and Future Directions

The present results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, despite the promising finding of a bidirectional relationship between identity coherence and depressive symptoms, it is important to note that the mechanisms underlying the relationship between identity development and depressive symptoms still remain poorly understood (Klimstra and Denissen 2017). Future research is necessary to attend to the underlying mechanisms that help explain the links of identity development with depressive symptoms and with psychopathology more broadly. Additionally, it should be noted that all participants were recent immigrants residing in major metropolitan areas with substantial and well-established Hispanic populations. Thus, it is unclear whether these findings can be generalized to immigrants in other cities or in “new receiving communities” where many Hispanic immigrants are settling (e.g., Kiang et al. 2011). Finally, given that in Western societies, adult commitments are not enacted until the mid-twenties (Schwartz et al. 2013), it is important for future studies to examine the directionality in identity processes and depressive symptoms among more acculturated youth and beyond adolescence.

Conclusion

Given that Hispanic youth are more likely to report depressive symptoms (Limon et al. 2016), and given that identity development may serve to anchor them during times of acute cultural change (Schwartz et al. 2006), there is a need to establish the directionality of the links between identity and psychopathology. Towards this end, the current study sought to determine the directional relationship between identity development and depressive symptoms among recently immigrated Hispanic youth. The results indicated a bidirectional relationship between identity coherence and depressive symptoms. These findings not only provide further evidence for the protective role that identity development plays during times of acute cultural transitions (Meca et al. 2017; Schwartz et al. 2006), but also emphasizes the need for research to examine how depressive symptoms, and psychopathology more broadly, may interfere with the establishment of a sense of self. It is hoped that the current study will inspire more research focused on the role that identity development plays among immigrant youth, and more broadly on the relationship between identity processes and psychopathology.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Maria-Rosa Velazquez, Tatiana Clavijo, Mercedes Prado, Alba Alfonso, Aleyda Marcos, Daisy Ramirez, Lissette Ramirez, Perlita Carrillo, Monica Pattarroyo, Daniel Soto, Juan A. Villamar, and Karina M. Lizzi for their work in conducting assessments, building rapport, and tracking families.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, co-funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Grant DA026594; S.J.S., PI; J.B.U., Co-PI). Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant R25 MH067127; Torsten B. Neilands).

Data Sharing and Declaration

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Biography

Alan Meca is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at Old Dominion University. His research program focuses on identity development, particularly personal and cultural identity, and the impact identity development has on psychosocial functioning and health disparities.

Julia C. Rodil is a graduate student in the Department of Psychology at Old Dominion University. She is interested in studying the development of cultural processes among youth. Currently, she studies how non-Hispanic White individuals develop attitudes towards ethnic/racial minorities, equity, and social justice.

James F. Paulson is an associate professor of Psychology at Old Dominion University and a pediatric psychologist at the Children’s Hospital of The King’s Daughters. His research focuses on parent characteristics, with an emphasis on psychopathology, and their impacts on parenting, coparenting, and the early family system, with an emphasis on pregnancy and the transition to parenthood.

Michelle Kelley is Professor and Chair in the Department of Psychology and Eminent Scholar at Old Dominion University. Her research focuses on mental health disorders and sexual violence among high-risk populations.

Seth J. Schwartz is a professor in the Department of Public Health Sciences at the University of Miami. His research interests are in personal and cultural identity processes, family relationships, health risk behaviors, and well-being and positive youth development.

Jennifer B. Unger is a professor in the Department of Preventive Medicine at the University of Southern California. Her research interests include psychological, social, and cultural influences on health-risk and health-protective behaviors in diverse populations.

Elma I. Lorenzo-Blanco is an assistant professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin. She received her PhD in clinical psychology and women’s studies at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Her research focuses on the role of socio-cultural and gender-related risk and protective factors on the emotional and behavioral well-being of Hispanic populations with the goal of developing tailored preventive intervention programs for Hispanic youth and families.

Sabrina E. Des Rosiers is an associate professor in the Department of Psychology at Barry University. Her research interests are centered on the examination of risk and protective factors at the individual, cultural, and social level for alcohol use, drug use and other externalizing problems among minority youth.

Melinda Gonzales-Backen is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Family and Child Sciences at Florida State University. Her research interests focus on how cultural stressors and strengths predict adolescent adjustment in the areas of self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and substance use.

Lourdes Baezconde-Garbanati is a Professor in the Department of Preventive Medicine at the Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California. Her research interests are on health disparities, community-based research and public health initiatives that explore the role of culture in health behaviors.

Byron L. Zamboanga is a Professor in the Department of Psychology at Smith College. His research program examines how alcohol cognitions and sociocultural factors are associated with drinking behaviors among adolescents and young adults.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Adams GR, & Marshall SK (1996). A developmental social psychology of identity: understanding the person-in-context. Journal of Adolescence, 19, 429–442. 10.1006/jado.1996.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD In: In Clogg C (ed.) 1990). Change scores as dependent variables in regression analysis Sociological methodology. (pp. 93–114). Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell; 10.2307/271083. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Asfour L, Huang S, Ocasio MA, Perrino T, Schwartz SJ, Feaster DJ, & Prado G (2017). Association between socio-ecological risk factor clustering and mental, emotional, and behavioral problems in Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26, 1266–1273. 10.1007/s10826-016-0641-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia M, Syed M, & Radmacher K (2008). Introduction and evidence from a longitudinal study of emerging adults In Azmitia M, Syed M & Radmacher K (Eds.), The intersections of personal and social identities: new directions for child and adolescent development (pp. 1–16). New York, NY: Wiley and Sons. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becht AI, Luyckx K, Nelemans SA, Goossens L, Branje SJT, Vollebergh WAM, & Meeus WHJ (2019). Linking identity and depressive symptoms across adolescence: aA multisample longitudinal study testing within-person effects. Developmental Psychology. Advance online publication 10.1037/dev0000742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. 2nd ed New York, NY: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Causadias JM, Vitriol JA, & Atkin AL (2018). The cultural (mis)attribution bias in developmental psychology in the United States. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 59, 65–74. 10.1016/j.appdev.2018.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, & Rensvold RB (1999). Testing factorial invariance across groups: a reconceptualization and proposed new method. Journal of Management, 25, 1–27. 10.1177/014920639902500101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Côté JE (2002). The role of identity capital in the transition to adulthood: the individualization thesis examined. Journal of Youth Studies, 5, 117–134. 10.1080/13676260220134403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Côté JE, & Levine CG (2015). Identity formation, youth, and development: a simplified approach. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti E, Meeus WHJ, Ritchie RA, Meca A, & Schwartz SJ (2014). Adolescent identity: is this the key to unraveling associations between family relationships and problem behaviors? In Scheier LM & Hansen WB (Eds.), Parenting and teen drug use: the most recent findings from research, prevention, and treatment (pp. 92–109). New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti E, Rubini M, Luyckx K, & Meeus W (2008). Identity formation in early and middle adolescents from various ethnic groups: from three dimensions to five statuses. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 983–996. 10.1007/s10964-007-9222-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davey A, & Savla J (2010). Statistical power analysis with missing data: a structural equation modeling approach. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Eichas K, Kurtines WM, Rinaldi RL, & Farr AC (2018). Promoting positive youth development: a psychosocial intervention evaluation. Psychosocial Intervention, 27, 1–13. 10.5093/pi2018a5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eichas K, Meca A, Montgomery MJ, & Kurtines WM (2014). Identity and positive youth development: advances in developmental intervention science In The Oxford handbook of identity development (pp. 337–354), New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH (1950). Childhood and society. New York, NY, USA: W. W. Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH (1968). Identity: youth and crisis. Oxford, England: Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Hamaker EL, Kuiper RM, & Grasman RPPP (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20, 102–116. 10.1037/a0038889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, & Ethier KA (2018). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 67, 1–114. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Perreira KM, & Fuligni AJ (2011). Ethnic label use in adolescents from traditional and non-traditional immigrant communities. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 719–729. 10.1007/s10964-010-9597-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimstra TA, & Denissen JJA (2017). A theoretical framework for the associations between identity and psychopathology. Developmental Psychology, 53, 2052–2065. 10.1037/dev0000356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Roosa MW, & Umaña-Taylor AJ (2009). Studying ethnic minority and economically disadvantaged populations: mMethodological challenges and best practices. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association; 10.1037/11887-000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Limon FJ, Lamson AL, Hodgson J, Bowler M, & Saeed S (2016). Screening for depression in Latino immigrants: a systematic review of depression screening instruments translated into Spanish. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 18, 787–798. 10.1007/s10903-015-0321-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83, 1198–1202. 10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx K, Goossens L, Soenens B, & Beyers W (2006). Unpacking commitment and exploration: preliminary validation of an integrative model of late adolescent identity formation. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 361–378. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx K, Klimstra TA, Duriez B, Van Petegem S, & Beyers W (2013). Personal identity processes from adolescence through the late 20s: age trends, functionality, and depressive symptoms. Social Development, 22, 701–721. 10.1111/sode.12027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx K, Schwartz SJ, Berzonsky MD, Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M, Smits I, & Goossens L (2008). Capturing ruminative exploration: extending the four-dimensional model of identity formation in late adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 58–82. 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE (2006). Ego identity and personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 20, 577–596. 10.1521/pedi.2006.20.6.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, & Cole DA (2007). Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods, 12, 23–44. 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade AW, Johnson EC, & Braddy PW (2008). Power and sensitivity of alternative fit indices in tests of measurement invariance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 568–592. 10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meca A, Eichas K, Quintana S, Maximin BM, Ritchie RA, Madrazo VL, Harari GM, & Kurtines WM (2014). Reducing identity distress: results of an identity intervention for emerging adults. Identity: an International Journal of Theory and Research, 14, 312–331. 10.1080/15283488.2014.944696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meca A, Sabet RF, Farrelly CM, Benitez CG, Schwartz SJ, Gonzales-Backen M, & Lizzi KM (2017). Personal and cultural identity development in recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents: links with psychosocial functioning. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 23, 348–361. 10.1037/cdp0000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK & Muthén BO (1998–2017). Mplus User’s Guide. Eighth Edition Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L (1977). The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal DA, Gurney RM, & Moore SM (1981). From trust on intimacy: a new inventory for examining Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 10, 525–537. 10.1007/BF02087944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG (2008). Reaping what you sew: immigration, youth, and reactive ethnicity. Applied Developmental Science, 12, 108–111. 10.1080/10888690801997341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, Prado G, Sharp EH, & Szapocznik J (2006). The role of ecodevelopmental context and self-concept in depressive and externalizing symptoms in Hispanic adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30, 359–370. 10.1177/0165025406066779. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Côté JE, & Arnett JJ (2005). Identity and agency in emerging adulthood: two developmental routes in the individualization process. Youth & Society, 37, 201–229. 10.1177/0044118X05275965. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Klimstra TA, Luyckx K, Hale III, W W, & Meeus W H J (2012). Characterizing the self-system over time in adolescence: internal structure and associations with internalizing symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 1208–1225. 10.1007/s10964-012-9751-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Kurtines WM, & Montgomery MJ (2005). A comparison of two strategies for facilitating identity formation processes in emerging adults: an exploratory study. Journal of Adolescent Research, 20, 309–345. 10.1177/0743558404273119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Montgomery MJ, & Briones E (2006). The role of identity in acculturation among immigrant people: theoretical propositions, empirical questions, and applied recommendations. Human Development, 49, 1–30. 10.1159/000090300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Des Rosiers SE, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Zamboanga BL, Huang S, & Szapocznik J (2014). Domains of acculturation and their effects on substance use and sexual behavior in recent Hispanic immigrant adolescents. Prevention Science, 15, 385–396. 10.1007/s11121-013-0419-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Meca A, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Cano MÁ, & Pattarroyo M (2017). Personal identity development in Hispanic immigrant adolescents: links with positive psychosocial functioning, depressive symptoms, and externalizing problems. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 898–913. 10.1007/s10964-016-0615-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Luyckx K, Meca A, & Ritchie RA (2013). Identity in emerging adulthood: reviewing the field and looking forward. Emerging Adulthood, 1, 96–113. 10.1177/2167696813479781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Wang W, & Olthuis JV (2009). Measuring identity from an Eriksonian perspective: two sides of the same coin? Journal of Personality Assessment, 91, 143–154. 10.1080/00223890802634266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva C, & Van Orden KA (2018). Suicide among Hispanics in the United States. Current Opinion in Psychology, 22, 44–49. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sireci SG, Wang Y, Harter J, & Ehrlich EJ (2006). Evaluating guidelines for test adaptations: a methodological analysis of translation quality. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37, 557–567. 10.1177/0022022106290478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stepler R, & Lopez MH (2016). U.S. lLatino pPopulation gGrowth and dDispersion hHas sSlowed sSince oOnset of the gGreat rRecession U.S. Latino Population Growth and Dispersion Has Slowed since Onset of the Great Recession. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2016/09/08/latino-population-growth-and-dispersion-has-slowed-since-the-onset-of-the-great-recession/. [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, & Juang LP (2014). Ethnic identity, identity coherence, and psychological functioning: testing basic assumptions of the developmental model. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20, 176–190. 10.1037/a0035330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, Walker LHM, Lee RM, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Zamboanga BL, Schwartz SJ, Armenta BE, & Huynh Q-L (2013). A two-factor model of ethnic identity exploration: implications for identity coherence and well-being. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19, 143–154. 10.1037/a0030564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorova IL, Falcón LM, Lincoln AK, & Price LL (2010). Perceived discrimination, psychological distress and health. Sociology of Health Illness, 32, 843–861. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doeselaar L, Klimstra TA, Denissen JJA, Branje S, & Meeus W (2018). The role of identity commitments in depressive symptoms and stressful life events in adolescence and young adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 54, 950–962. 10.1037/dev0000479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]