The primary function of vitamin D in higher vertebrates is to regulate mineral homeostasis through direct actions on intestinal calcium (Ca) and phosphate (P) absorption, bone mineral resorption, and renal mineral reabsorption. Vitamin D itself is inactive and must undergo sequential modification via two specific chemical reactions, first in the liver to 25(OH)D3 by the enzyme CYP2R1, and then in the kidney to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3 or calcitriol] by the tightly regulated enzyme CYP27B1 (1). Calcitriol, whose level is also modulated via renal CYP24A1–mediated degradation, is then secreted into the blood as an active endocrine hormone and delivered to distant target tissues.

Production of calcitriol in nonrenal target tissues

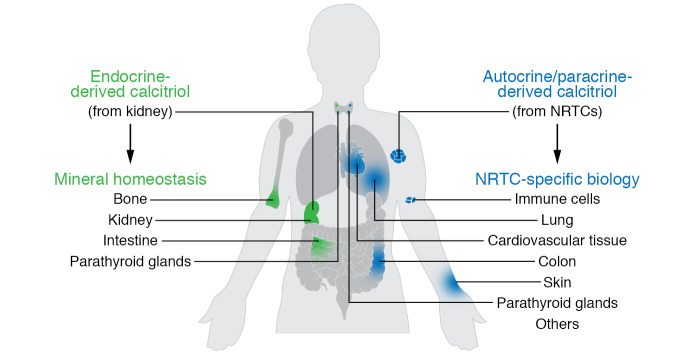

Research over the past several decades has suggested that the conversion of 25(OH)D3 to calcitriol also occurs in a myriad of nonrenal tissues and cells (NRTCs) that include the skin, parathyroid glands, bone cells, both cardiovascular and immune cells, and many others (2). The basis for this idea stems from initial immunocytochemical observations that indicate that CYP27B1 is also expressed in NRTCs, albeit at very low levels relative to levels in the primary renal source. Not surprisingly, these observations stimulated new research aimed at determining details of this previously undescribed source of calcitriol (3). This work has led to an important hypothesis proposing that renal endocrine calcitriol is predominantly linked to the regulation of mineral metabolism, whereas local NRTC production of this hormone may be central to the control of the numerous noncalcemic biological activities identified in these cell types (Figure 1). This hypothesis is supported through further observations indicating that the regulation of Cyp27b1 expression in NRTCs differs substantially from that in the kidney (4). Thus, while renal Cyp27b1 expression is tightly modulated by parathyroid hormone (PTH), calcitriol and phosphaturic FGF23, these mineralotropic hormones are inactive in NRTCs, where inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, TNF-α, LPS, and probably others prevail (5). The discovery has, in part, drawn numerous investigators into the exploration of vitamin D action in immune cells and its role as an antiinflammatory agent in target cells (5). Interestingly, in spite of decades-earlier revelations that PTH and calcitriol itself, as well as the more recently discovered FGF23, constitute major modulators of renal CYP27B1 (4), a mechanistic basis for this regulation has only recently begun to emerge (6, 7). On the other hand, insight into how Cyp27b1 is regulated by inflammatory modulators has been limited in vivo (8). Irrespective of these issues, it is noteworthy that, although local production of calcitriol in NRTCs has gained wide acceptance in the field, key fundamental insights supporting the relevance of this process and its biological consequences remain outstanding. In this Viewpoint, we suggest that additional information will be essential to fully understand the nature of the autocrine production of calcitriol by NRTCs and may also be critical for designing future clinical trials aimed at deciphering the role of vitamin D supplementation in both health and disease.

Figure 1. Model summarizing two potential biological spheres of vitamin D3 influence.

Renal endocrine calcitriol may predominantly link to the regulation of mineral metabolism, while local NRTC production may control other numerous noncalcemic biological activities.

The importance of adequate blood levels of vitamin D

Ironically, a current conflict exists within the field as to what might constitute adequate levels of circulating 25(OH)D3, the substrate for calcitriol production, in healthy humans, and of supplemental vitamin D required to maintain those levels. Indeed, while the Institute of Medicine has concluded that 25(OH)D3 levels at or above 20 ng/mL are adequate to protect the skeleton, the Endocrine Society has concluded that 30 ng/mL or more is appropriate (9). Although this issue remains unresolved and is not the topic of this Viewpoint, the absence of an appreciation for how these levels might impact the differential synthesis of calcitriol in the kidneys and in NRTCs has led to considerable uncertainty as to how clinical trials and the parameters of those trials should be established. This is particularly true relative to the effects of vitamin D in cancer prevention, cardiovascular protection, immune disease, and diabetes, as well as in other maladies for which a protective, noncalcemic role for vitamin D has been indicated. Despite the potential relevance of this information, numerous randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have been conducted over the past several decades; unfortunately, results from the majority of these have not been particularly illuminating. Commentary on the details of these trials, most of which showed no effect, has been extensive and will not be considered here (10); three recent trials, however, merit reference. The recently concluded VITAL trial (VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL), aimed at assessing the ability of supplemental vitamin D to prevent cancer and cardiovascular disease, resulted in the general absence of an impact of the vitamin on either of these diseases, although a modest potential effect on cancer was noted upon careful secondary evaluation (10, 11). A second trial conducted to determine the impact of high-dose supplemental vitamin D on prediabetic progression did not reach statistical significance (12). Finally, a clinical trial aimed at assessing the impact of supplemental vitamin D on patients with tuberculosis also found no effect on the disease, despite noted elevations in 25(OH)D3 levels (10). This study did, however, underscore the importance of using reliable assays to measure vitamin D metabolites with accuracy. These trial results join the many others that have failed to provide substantive evidence for vitamin D as an effective treatment for disease progression.

Interestingly, vitamin D may also play a beneficial role in a wide number of infectious diseases, including that induced by SARS–CoV-2, the virus central to the ongoing global coronavirus pandemic (13). Indeed, much work in vitro has already focused on mechanisms by which vitamin D might function to protect patients from viral infection, including the potential ability of vitamin D to regulate ACE2 and its potential role as an antiinflammatory agent to combat the so-called “cytokine storm” associated with SARS–CoV-2. Although correlative studies now abound, the current challenge will be to conduct appropriate RCTs to prove that the effects seen in vitro and in animal models can also be observed with respect to this coronavirus, and multiple efforts are now underway. Unfortunately, virtually all the issues noted above that have resulted in uninformative clinical trial outcomes with other diseases continue to apply to SARS–CoV-2 as well.

Unresolved mechanisms relevant to NRTC production of calcitriol

The mechanistic in vivo work alluded to earlier has led to a basic understanding of the genomic regulation of renal Cyp27b1 in mice (6, 7, 14); nevertheless, its relevance to humans remains unexplored. From a genomic perspective, however, it is worth mentioning that the CYP27B1 and CYP24A1 genes of both species are similarly organized and that the regulation of human CYP27B1 by PTH, FGF23, and calcitriol in the kidneys and by LPS in NRTCs has also been well documented (4, 6, 7, 14), suggesting potentially similar mechanistic underpinnings. Fundamental questions pertinent to the local production of calcitriol for both species still exist, however, and objectives are worth enumerating. First is the need to determine whether NRTCs biosynthesize calcitriol in healthy subjects in vivo, as has been solidified unequivocally in patients with a variety of granulomatous diseases (8), and especially to assess these levels relative to the kidneys. Equally important will be an evaluation of whether this synthesis can exert a measurable effect on vitamin D receptor activation mechanisms to alter gene expression and modify cellular function. Second is the need to assess whether and if locally produced calcitriol is routinely secreted by NRTCs in health as well as in disease (5, 8). Third is the necessity to determine whether the activity of locally produced calcitriol is dependent on or influenced by the circulating levels of endocrine-derived calcitriol. Finally, there is a critical need to determine whether circulating concentrations of 25(OH)D3 substrate differentially affect the production of calcitriol in the kidneys and in NRTCs. Lower levels of 25(OH)D3 are known to rapidly saturate the kidney enzyme, whereas higher levels may be needed to provoke calcitriol production in NRTCs (8). This insight is important, because cellular uptake of 25(OH)D3, rather than altered enzyme affinity, is likely the primary determinant for NRTC production of calcitriol (8). It is noteworthy that the components of an uptake mechanism for 25(OH)D3 that have been previously defined for the kidney are generally either few or absent in NRTCs; viable alternatives for the latter will have to be explored (3). This issue is particularly critical, since blood levels of unbound 25(OH)D3 are postulated to be essential for cellular uptake, as advanced by advocates of the free-hormone hypothesis (15, 16). Resolution of these issues will be essential for understanding the role of calcitriol production in NRTCs and perhaps for the design of future clinical studies aimed at assessing the levels of vitamin D supplementation necessary to maintain health and combat specific disease states.

Models for characterizing features of NRTC calcitriol production

A unique animal model is required to assess the features of NRTC production of calcitriol described above. Several characteristics of such a model include (a) a highly attenuated circulating endocrine calcitriol level facilitated through selective downregulation of Cyp27b1 expression in the kidneys, (b) full retention of Cyp27b1 expression and regulation in NRTCs, and (c) an ability to precisely regulate circulating levels of either vitamin D3 or 25(OH)D3 experimentally under conditions of tightly controlled mineral metabolism. Although a kidney-selective Cyp27b1-null mouse is not yet available and global Cyp27b1-null mice do not retain NRTC production of calcitriol (17), a Cyp27b1 pseudo-null mouse with the above characteristics has recently been generated (7). This mouse strain was derived directly from our identification of a kidney-specific genomic module that controls Cyp27b1 expression in mice. Accordingly, deletion of this module led to a dramatic loss of basal and regulated expression of renal Cyp27b1 in these mice, yet was without effect on Cyp27b1 expression in NRTCs. This Cyp27b1 pseudo-null mouse exhibits hypocalcemia, hyperparathyroidism, low FGF23 expression, and very low levels of circulating calcitriol as well as an aberrant Cyp27b1-null–like skeleton. Importantly, while key elements of this phenotype are normalized when systemic mineral metabolism and low levels of renal Cyp24a1 are fully restored through dietary means, detectable blood levels of calcitriol are completely eliminated (7). This model will be extremely useful for exploring the missing features of NRTC production of calcitriol, as enumerated above, and assessing the role of calcitriol in both health and disease. It is our view that the details obtainable through this avenue of investigation in the mouse will likely advance our current understanding of the synthesis of calcitriol in NRTCs and provide potential clinically relevant insights as well.

Acknowledgments

We thank Seong M. Lee and Nancy A. Benkusky as well as previous members of our laboratory for their contributions to this work. We also thank Glen Jones and Martin Kaufmann for their contributions and insights. This Viewpoint was supported by the NIH award DK117475 (to JWP).

Version 1. 07/27/2020

Electronic publication

Version 2. 09/01/2020

Print issue publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Copyright: © 2020, American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Reference information: J Clin Invest. 2020;130(9):4519–4521. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI141334.

Contributor Information

J. Wesley Pike, Email: jpike@wisc.edu.

Mark B. Meyer, Email: markmeyer@wisc.edu.

References

- 1.Jones G, Prosser DE, Kaufmann M. Cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism of vitamin D. J Lipid Res. 2014;55(1):13–31. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R031534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewison M, et al. Extra-renal 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1alpha-hydroxylase in human health and disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103(3-5):316–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chun RF, et al. Vitamin D binding protein and the biological activity of vitamin D. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:718. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bikle D, Christakos S. New aspects of vitamin D metabolism and action - addressing the skin as source and target. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(4):234–252. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hewison M. Vitamin D and innate and adaptive immunity. Vitam Horm. 2011;86:23–62. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386960-9.00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer MB, et al. A kidney-specific genetic control module in mice governs endocrine regulation of the cytochrome P450 gene Cyp27b1 essential for vitamin D3 activation. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(42):17541–17558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.806901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer MB, et al. Targeted genomic deletions identify diverse enhancer functions and generate a kidney-specific, endocrine-deficient Cyp27b1 pseudo-null mouse. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(24):9518–9535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.008760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hewison M, Adams JS. Extrarenal 1α-ydroxylase. In: Feldman D, Pike JW, Adams JS, eds. Vitamin D. 3rd ed. Academic Press; 2011:777–804. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouillon R. Comparative analysis of nutritional guidelines for vitamin D. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13(8):466–479. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giustina A, et al. Consensus statement from 2nd International Conference on Controversies in Vitamin D. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2020;21(1):89–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiemstra T, Lim K, Thadhani R, Manson JE. Vitamin D and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. doi: 10.1210/jc.2019-00194. [published online ahead of print February 10, 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pittas AG, et al. Vitamin D supplementation and prevention of type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(6):520–530. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant WB, et al. Evidence that vitamin D supplementation could reduce risk of influenza and COVID-19 infections and deaths. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):E988. doi: 10.3390/nu12061620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer MB, et al. A chromatin-based mechanism controls differential regulation of the cytochrome P450 gene Cyp24a1 in renal and non-renal tissues. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(39):14467–14481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.010173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie Z, Wang X, Bikle DD. Editorial: Vitamin D binding protein, total and free vitamin D levels in different physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020;11(40):1–3. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bikle DD, Gee E. Free, and not total, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D regulates 25-hydroxyvitamin D metabolism by keratinocytes. Endocrinology. 1989;124(2):649–654. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-2-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dardenne O, Prudhomme J, Hacking SA, Glorieux FH, St-Arnaud R. Rescue of the pseudo-vitamin D deficiency rickets phenotype of CYP27B1-deficient mice by treatment with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3: biochemical, histomorphometric, and biomechanical analyses. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(4):637–643. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]