Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) potentially increases the risk of thromboembolism and stroke. Numerous case reports and retrospective cohort studies have been published with mixed characteristics of COVID-19 patients with stroke regarding age, comorbidities, treatment, and outcome. We aimed to depict the frequency and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients with stroke.

Methods

PubMed and EMBASE were searched on June 10, 2020, to investigate COVID-19 and stroke through retrospective cross-sectional studies, case series/reports according to PRISMA guidelines. Study-specific estimates were combined using one-group meta-analysis in a random-effects model.

Results

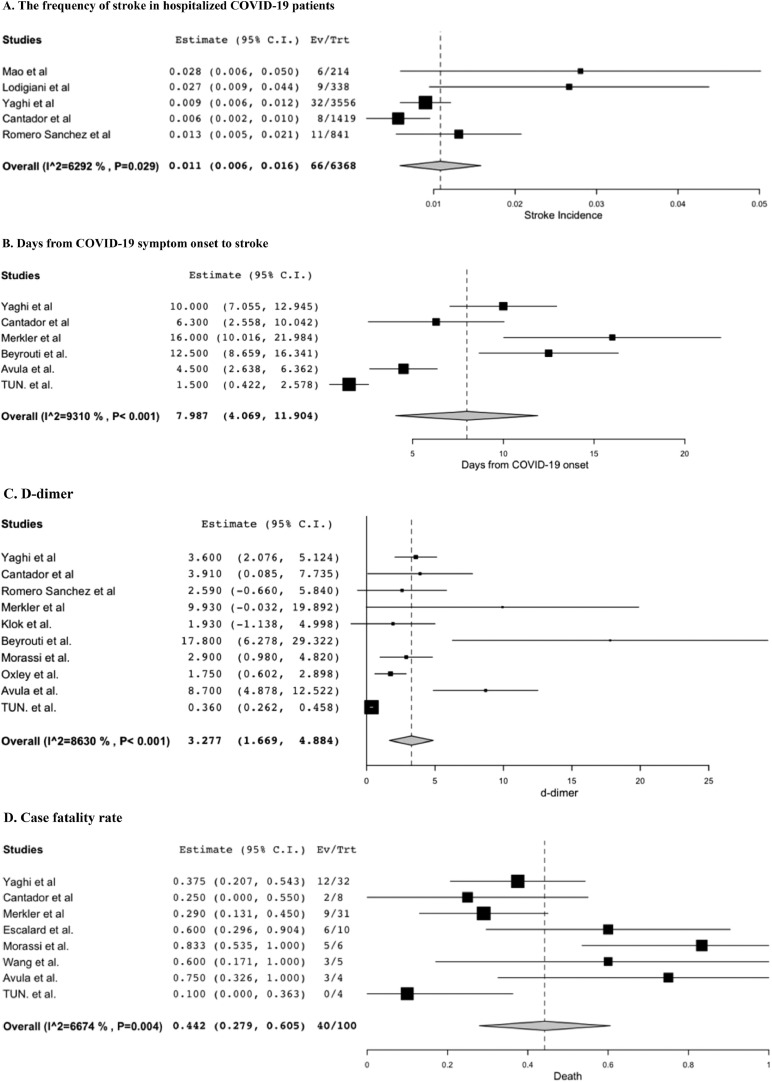

10 retrospective cohort studies and 16 case series/reports were identified including 183 patients with COVID-19 and stroke. The frequency of detected stroke in hospitalized COVID-19 patients was 1.1% ([95% confidential interval (CI)]: [0.6-1.6], I2 = 62.9%). Mean age was 66.6 ([58.4-74.9], I2 = 95.1%), 65.6% was male (61/93 patients). Mean days from symptom onset of COVID-19 to stroke was 8.0 ([4.1-11.9], p< 0.001, I2 = 93.1%). D-dimer was 3.3 μg/mL ([1.7-4.9], I2 = 86.3%), and cryptogenic stroke was most common as etiology at 50.7% ([31.0-70.4] I2 = 64.1%, 39/71patients). Case fatality rate was 44.2% ([27.9-60.5], I2 = 66.7%, 40/100 patients).

Conclusions

This systematic review assessed the frequency and clinical characteristics of stroke in COVID-19 patients. The frequency of detected stroke in hospitalized COVID-19 patients was 1.1% and associated with older age and stroke risk factors. Frequent cryptogenic stroke and elevated d-dimer level support increased risk of thromboembolism in COVID-19 associated with high mortality. Further study is needed to elucidate the pathophysiology and prognosis of stroke in COVID-19 to achieve most effective care for this population.

Keywords: COVID-19, stroke, SARS-CoV2, Meta-analysis, Systematic review

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a novel coronavirus that caused ongoing worldwide pandemic.1 Clinical features of COVID-19 range from asymptomatic to fever, cough, shortness of breath, and even death.2 Associated neurological manifestation included mild disease such as dizziness, headache, impaired sense of smell and taste, and polyneuropathy, as well as impaired consciousness, stroke, seizure, and encephalitis.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 – 11 Increasing evidence suggests that coagulopathy due to COVID-19 leads to systemic arterial and venous thromboembolism including but not limited to acute ischemic stroke.12, 13, 14 – 15 Initial case reports with stroke and COVID-19 were alarming consisted of young patients without comorbidities,16 however, there were also reports of older patients with stroke risk factors and worse outcome.17 There were mixed laboratory data and case fatality rate in case series making it difficult to apprehend the overall characteristics of stroke with COVID-19. Herein, this systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted to illustrate the reported frequency of stroke in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, as well as the demographic and the clinical characterization of all reported patients with COVID-19 and stroke.

Methods

Protocol and registration

A review protocol does not exist for this analysis.

Eligibility criteria

Included studies met the following criteria: the study design was an observational study or a case series or report, the study population was patients with COVID-19 patients and stroke. Articles that do not contain original data of the patients (e.g. guideline, editorial, review, and letter) were excluded from the secondary review.

Information sources and search

All observational studies, case series, and case reports which included patients with COVID-19 and stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) were identified using a 2-level strategy. First, databases including PubMed and EMBASE were searched through June 10th, 2020. Search terms included ((SARS-CoV2) OR (COVID-19)) AND ((stroke) OR (cerebrovascular accident) OR (cerebral infarction)). We did not apply language limitations.

Study selection and data collection process

Relevant studies were identified through a manual search of secondary sources including references of initially identified articles, reviews, and commentaries. All references were downloaded for consolidation, elimination of duplicates. Two independent authors (M.Y. and T.K.) reviewed the search results separately to select the studies based on present inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data items

Outcomes included age, sex, comorbidities, symptoms, days from COVID-19 symptom onset to stroke, laboratory data such as d-dimer, C-reactive protein (CRP), and cardiac troponin, etiology, treatment, and case fatality rate. Among symptoms of stroke, any change in mental status such as lethargy, confusion, and coma were summated as altered mental status; this included patients who presented with new change in mental status, and those who continued to be comatose after weaning off of sedation for mechanical ventilation. Fall or syncope was not included in this category. Corresponding authors were contacted individually if there were any values suspicious for a misspelling.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Risk of bias in individual studies was reviewed using assessment of risk of bias in prevalence studies.18

Summary measures and synthesis of results

To attempt to calculate frequency of stroke in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, retrospective cohort studies focused on hospitalized COVID-19 patients were utilized. For other estimates (age, days from symptom onset of COVID-19 to stroke diagnosis, d-dimer, CRP, troponin, and case fatality rate), retrospective cohort studies which targeted other population and case series as well as case reports were added to the studies above and combined using one-group meta-analysis in a random-effects model using DerSimonian-Laird method for continuous value and Wald method for discrete value with OpenMetaAnalyst version 12.11.14 (available from http://www.cebm.brown.edu/openmeta/). The frequency of common comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, acute coronary syndrome /coronary artery disease), atrial fibrillation, stroke/transient ischemic attack, and malignancy), etiology of stroke if specified in the articles, and treatment (tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), mechanical thrombectomy, and anticoagulation were calculated by summation of events divided by the number of total patients from all studies whose information is available for each value. Any anticoagulation therapy except prophylaxis for deep venous thrombosis preceding the stroke diagnosis was included in the calculation, and whether it was intended for treatment of stroke, therapeutic anticoagulation for other thromboembolic complication, or part of treatment protocol for acute respiratory distress syndrome in COVID-19, was delineated in the result section when available. The ProMeta 3 software was used to perform funnel plots (https://idostatistics.com/prometa3/) for age. We did our systematic review and meta-analysis according to PRISMA guidelines.

Results

Study selection and study characteristics

The database search identified 215 articles that were reviewed based on the title and abstract. Of those, 186 articles were excluded based on article type (clinical guidelines, consensus documents, reviews, systematic reviews, and conference proceedings), conference abstracts, irrelevant topics, and articles without stroke with COVID-19. Twenty-nine articles met the inclusion criteria and were assessed for the systematic review (Fig. e-1). Nine articles were excluded for reasons including duplicate reports and article type. Six articles were added after the second search on June 10, 2020. There were 10 retrospective cohort studies, 6 case series, and 10 case reports with patients of interest.3 , 12 , 13 , 16 , 17 , 19, 24, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 – 39

Risk of bias in individual studies

Summary of risk of bias for prevalence studies for each retrospective cohort study was shown in Table e-1.

Results of individual studies and synthesis of results

Extracted data as above is shown in Tables 1 and 2 for the retrospective cohort studies, and in Table e-2 for the case series and case reports.

Table 1.

Results of Systematic Review with Cohort Studies of COVID-19 Positive Patients - Basic Characteristics.

| Study | Country | Population | Number of Hospitals | Cohort size | Stroke, % (N) | Age | Male, % (N) | Comorbidities, % (N) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTN | DLP | DM | ACS/CAD | AF | Stroke/TIA | Malignancy | ||||||||

| Mao et al. | China | Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection between 1/16-2/19, 2020 | 3 | 214 | 2.8% (6) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Lodigiani et al. | Italy | Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection between 2/13-4/10, 2020 | 1 | 338 | 2.7% (9) | 68.4±5.9 | 66.7% (6) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 11.1% (1) |

| Yaghi et al. | USA | Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection between 3/15-4/19, 2020 | 3 | 3556 | 0.9% (32) | 63±25 | NA | 56.3% (18) | 59.4% (19) | 34.4% (11) | 15.6% (5) | 18.8% (6) | 3.1% (1) | NA |

| Cantador et al. | Spain | Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection between 2/1-4/21, 2020 | 1 | 1419 | 0.56% (8) | 76.4±7.1 | 87.5% (7) | 100% (8) | 87.5% (7) | 50% (4) | 37.5% (3) | 25% (2) | 25% (2) | 62.5% (5) |

| Romero Sanchez et al. | Spain | Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection in March 2020 | 2 | 841 | 1.3% (11) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Merkler et al. | USA | Patients with emergency department visits or hospitalizations with COVID-19 infection between 3/4-5/2, 2020 | 2 | 2132 | 1.5% (31) | 69±16.2 | 58.1% (18) | 96.8% (30) | 54.8% (17) | 74.2% (23) | 51.6% (16) | 54.8% (17) | NA | NA |

| Klok et al. | Netherland | ICU patients with COVID-19 | 1 | 184 | 2.7% (5) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Radmanesh et al. | USA | COVID 19 positive patients who underwent MRI or CT in 3/1-3/31 at NYU | 1 | 242 | 5.4% (13) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Escalard et al. | France | Patients who had stroke with LVO from 3/1 to 4/15 | 1 | 37 | 27% (10)* | 59.5 [54, 71] | 80% (8) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kihira et al. | USA | Patients who had confirmed stroke in 3/16-4/5 | 6 | 48 | 37.5% (18)* | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Value is shown as median [Q1, Q3] or mean±SD unless specified otherwise. Abbreviations: ACS/CAD – acute coronary syndrome/coronary artery disease; AF – atrial fibrillation; DM – Diabetes; HTN – hypertension; DLP – dyslipidemia; LVO: large vessel occlusion; NA – non-applicable; TIA – transient ischemic attack. * - who were COVID-19 positive.

Table 2.

Results of Systematic Review with Cohort Studies of COVID-19 Positive Patients – Characteristics of Stroke, Treatment, and Mortality.

| Study | Ischemic, % (N) | Days from COVID-19 symptom onset | Laboratory data |

Etiology |

Treatment |

Mortality, % (N) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-dimer (μg/mL) | CRP (mg/L) | Cardiac troponin (ng/mL) | Cryptogenic | Cardioembolic | Atherothrombic | tPA | Mechanical thrombectomy | AC | ||||

| Mao et al. | 83.3% (5) | 9 [range 1-18]* | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Lodigiani et al. | 100% (9) | NA | 3.6 [0.4, 6.3] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 22.2% (2) | 22.2% (2) | 88.9% (8) | NA |

| Yaghi et al. | 100% (32) | 10 [5, 16.5] | 3.913 [2.549-10.000] | 101.1 [38.8, 214.3] | 0.7 [0.3125, 1.36]*3 | 65.6% (21) | 21.9% (7) | 6.3% (2) | 12.5% (4) | 21.9% (7) | 78.1% (25) | 37.5% (12) |

| Cantador et al. | 100% (8) | 6.3±5.4 | 2.589 [0.735, 8.156] | 100.5 [27, 206] | NA | 25% (2) | 25% (2) | 37.5% (8) | 12.5% (1) | NA | Prophylactic 37.5% (3), therapeutic 12.5% (2) | 25% (2) |

| Romero Sanchez et al. | NA | 10⁎2 | 9.929±28.286 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Merkler et al. | NA | 16 [5, 28] | 1.93 [0.559, 5.285] | NA | 0.03 [0.03, 0.09] | 51.6% (16) | 41.9% (13) | NA | 9.7% (3) | 6.5% (2) | NA | 29% (9) |

| Klok et al. | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Radmanesh et al. | 100% (13) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 23.1% (3) | NA | NA |

| Escalard et al. | 100% (10) | 6 [range 2-18]* | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 50% (5) | 100% (10) | NA | 60% (6) |

| Kihira et al. | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Days from COVID-19 symptom onset, D-dimer, C-reactive protein (CRP), cardiac troponin – shown as median [Q1, Q3] or mean±SD unless specified otherwise. *1 – specified as “range” in the original article. *2 - mean. *3 - Only 15 patients out of 32 patients had available value in the article. AC – anticoagulation; NA – non-applicable; tPA – tissue plasminogen activator.

Among the 10 retrospective cohort studies, 5 studies defined their population as hospitalized COVID-19 patients, 1 from China,3 1 from Italy,12 2 from Spain,19 , 21 and 1 from USA,22 with total of 6,368 individuals. The reported frequency of stroke in hospitalized COVID-19 patients was 1.1% ([95% confidential interval]: [0.6-1.6], I2=62.9%, 66/6,368 patients)3 , 12 , 19 , 21 , 22 (Fig. 1 A). The other 5 retrospective cohort studies set their population differently and thus were excluded from the calculation of the frequency of stroke in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.13 , 20 , 37 – 39

Figure 1.

Forest plots for characteristics of stroke patients with COVID-19 (random-effects model); (A): The frequency of stroke in hospitalized COVID-19 patients; (B): Days from COVID-19 symptom onset to stroke; (C): D-dimer; (D): Case fatality rate.

All 10 retrospective cohort studies and 16 case series and case reports were included for further analysis regarding age, symptoms of stroke, symptoms of COVID-19, days from COVID-19 onset to stroke diagnosis, d-dimer, CRP, troponin, the frequency of cryptogenic stroke as etiology if it is specified in the article, location of affected major intracranial arteries if specified, and mortality using one-group meta-analysis in a random-effects model (Fig. 1B-D, Fig. e-2). Mean age was 66.6 ([58.4-74.9], I2=95.2%). There was slight male preponderance at 65.6% (61/93 patients). The frequency of comorbidities and stroke risk factors were hypertension 69.4% (75/108 patients), dyslipidemia 44.4% (48/108 patients), diabetes 43.5% (47/108 patients), acute coronary syndrome/coronary artery disease 26.9% (29/108 patients), atrial fibrillation 23.1% (25/108 patients), prior stroke/transient ischemic attack 10.4% (8/77 patients), and malignancy 14.8% (8/54 patients). Of note, prior anticoagulation status for patients with atrial fibrillation was not available in majority of included studies, and thus was not included in this analysis.

Of those who stroke type (ischemic vs hemorrhagic) were described, 96.6% (113/117 patients) had ischemic stroke. The three most common presenting symptoms of stroke gathered mainly from case series and case reports were unilateral weakness (65.7%, 23/35 patients), altered mental status (51.4%, 18/35 patients), and dysarthria (34.3%, 12/35 patients). As for symptoms of COVID-19, cough was most common (77.6%, 59/76 patients), followed by fever (63.2%, 48/76 patients) and dyspnea or hypoxia (62.1%, 41/66 patients). Mean days from symptom onset of COVID-19 to stroke was 8.0 ([4.1-11.9], I2=93.1%) (Fig. 1B). Mean d-dimer was 3.3 μg/mL ([1.7-4.9], I2=86.3%) (Fig. 1C) and elevated, mean CRP was 127.8 mg/L ([100.9-154.6], I2 = 0%) also elevated, however, mean troponin was 0.051 ng/mL ([0.002-0.099], I2 = 91.5%) and was not significantly high. In regards to the etiology of stroke specified by the authors, 50.7% was cryptogenic ([31.0-70.4] I2=64.1%, 39/71patients). Affected major intracranial arteries were middle cerebral arteries (30.5%, 25/82 patients), internal carotid arteries (18.3%, 15/82 patients), vertebrobasilar arteries (7.3%, 6/82 patients), posterior cerebral arteries (3.7%, 3/82 patients). Of those patients whose detail of stroke localization was available, 29.2% had multifocal stroke (14/48 patients). As for acute treatment, 21.8% (24/110 patients) received tPA, 28.3% (34/120 patients) underwent mechanical thrombectomy. Anticoagulation was documented in 61.3% (46/75 patients); of those, 1 patient was getting therapeutic anticoagulation for pulmonary embolism before diagnosis of stroke,23 and another patient was started on therapeutic anticoagulation as part of treatment for acute respiratory distress syndrome from COVID-19, however the timing of anticoagulation in relation to the stroke occurrence was unavailable.25 Other patients were started on anticoagulation therapy for stroke treatment. Case fatality rate was 44.2% (40/100 patients) ([27.9-60.5], I2=66.7%) (Fig. 1D). Funnel plot for age is shown in Supplemental Figure e-3 (Egger's test: p=0.97).

Discussion

This systematic review of 26 studies identified 183 COVID-19 patients with stroke. The salient findings of the study can be summarized as the followings; (1) the frequency of stroke in hospitalized COVID-19 patients was 1.1%, with mean days from COVID-19 symptom onset to stroke at 8 days, most commonly cryptogenic; (2) even with early case series with younger patients without a pre-existing medical condition, the mean age was 66.6, with slight male preponderance (65.6%); (3) stroke risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and prior strokes were common as comorbidities; altered mental status was as frequent as 51.4% as presenting symptom of stroke; (4) elevation of d-dimer and CRP were reproduced after synthesis of results; (5) case fatality rate was as high as 44.2% in patients with COVID-19 and stroke.

We revealed the frequency of stroke in hospitalized COVID-19 patients was 1.1%. Stroke incidence in general population is estimated from 0.6 to 0.8%.40 Infection, particularly systemic upper respiratory illness is an important precipitating risk factor for acute ischemic stroke.41, 42 – 43 Notably, Boehme et al. reported that risk of acute stroke increases 9 times in young population aged 18-45 within 15 days from onset of influenza-like illness.41 Furthermore, patients with emergency department visits and hospitalizations with COVID-19 were reported to be approximately seven times as likely to have an acute ischemic stroke as compared to patients with emergency department visits or hospitalizations with influenza.20 Previous study revealed that stroke risk increases after a systemic respiratory tract infection at most within 3 days from symptom onset.43 On the contrary, the days from symptom onset to stroke with COVID-19 in our study was 8 days, longer than other systemic respiratory infection in pre-COVID-19 era,43 potentially supporting late thromboembolism complications caused by immune-mediated coagulopathy of COVID-19.44 However, this duration between symptom onset of COVID-19 and stroke was variable as represented by a high heterogeneity, and it is notable that some patients presented with stroke even without COVID-19 symptoms.16 Most common etiology of stroke was cryptogenic up to 50.7% which is twice as high as that of general population at 25%.45 29.2% had multifocal stroke among patients whose detail of stroke was available. Collectively, SARS-CoV-2 is potentially a higher precipitating factor for acute ischemic stroke compared to other classic respiratory infection such as influenza, possibly via immune mediated coagulopathy.12 – 15

Early in the course of the pandemic, several cases of younger patients without comorbidities were reported16 , 26 , 27; however, our synthesized results re-demonstrated classic demographics of the population who are at risk for stroke even in COVID-19 patients, including older age, male gender, and pre-existing medical condition such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes. Altered mental status was seen in 51.4% as presenting symptom of stroke, which is more frequent than stroke in general (15–23% in one study).46 Decreased level of consciousness is reported to be a risk factor for missed diagnosis of stroke in emergency room.47 Along with delayed presentation and concurrent fever, this could potentially explain the relatively low rates of tPA administration; however, further investigation is needed to depict the safety and effectivity of tPA in patients with stroke and COVID-19.

D-dimer and CRP were elevated on average at 3.3 μg/mL and 127.8 mg/L respectively in our study. Previous report pointed out d-dimer greater than 1 μg/mL is a risk factor for severe COVID-19 and mortality.48 , 49 Other report demonstrated d-dimer >2.5 μg/mL and CRP >200 mg/L were related to critical illness of COVID-19, which may be associated with higher risk of hyper-inflammatory states and hypercoagulability and resultant pulmonary emboli and microscopic emboli.50 As a marker for acute inflammation and coagulopathy, elevated d-dimer was an adverse prognostic factor in H1N1 influenza in 200951 , 52 and also in acute ischemic stroke.53 Since elevated d-dimer could be used as a risk assessment biomarker of recurrent stroke in general54 , 55 and previous observational study showed that anticoagulation might be associated with improved outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-1956, patients with stroke and COVID-19 might benefit from anticoagulation therapy, especially with cryptogenic stroke.56 However, patients who are intubated under sedation with poor neurological exam warrant extra caution before initiating anticoagulation, since those patients could be at higher risk of ischemic stroke that could have hemorrhagic conversion undetected.57 Neuroimaging should be considered in this population prior to anticoagulation to avoid iatrogenic hemorrhagic conversion of undiagnosed ischemic stroke.

Lastly, the case fatality rate in this population with stroke and COVID-19 was conspicuously high at 44.2%. It is higher than mortality from stroke in general population that differs significantly by age; according to a report of Medicare beneficiaries over the time period 1995 to 2002, the 30-day mortality rate was: 9% in patients 65 to 74 years of age, 13.1% in those 74 to 84 years of age, and 23% in those older than 85 years of age.40 Mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients reported in the early course of pandemic ranged from 4 to 28%.48 , 58, 59, 60 – 61 This discrepancy in mortality of COVID-19 patients with and without stroke could be secondary to withdrawal of medical care when the neurological prognosis is grave17 , 28 , 33; another possibility is that stroke is part of multi-organ failure and systemic coagulopathy whose mortality is higher than COVID-19 patients in general. Notably, prior stroke has been described as a risk factor for severe disease in COVID-19 patients even without concurrent acute stroke, which could potentially support vulnerability of patients with cerebrovascular disease to COVID-19 from undetermined cause.62 The cause of death in this population remains unclear with our study due to limited details about the cause of death from large cohort studies. Further study is needed to elucidate pathophysiology and risk factors for stroke as well as outcome and best treatment measures in hope to lower mortality in COVID-19 patients with stroke.

This study has several limitations. First, this systematic review covered a brief period, and therefore the sample size may still be limited. Second, only limited value was available ubiquitously in the reviewed studies. Third, there was a substantial heterogeneity in patient population given high I2 and different inclusion criteria of the studies used in this analysis, such as hospitalization, requirement of intensive care, and large vessel occlusion that warranted mechanical thrombectomy. In addition, the case reports and case series that were included in this review could potentially have publication bias that more severe cases in a younger population without risk factors with large stroke burden tend to be published as this type of articles, compared to those who had stroke risk factors as comorbidities and suffered small lacunar strokes and COVID-19. Furthermore, reported incidence of acute stroke could be lower than actual, since subtle signs of small stroke could have been missed by the providers especially when patients with COVID-19 were sedated and intubated.

Conclusions

This systematic review assessed the clinical characteristics of stroke in patients with COVID-19. The frequency of stroke in hospitalized COVID-19 patients was 1.1% and associated with older age and stroke risk factors. Frequent cryptogenic stroke and elevated d-dimer level support increased risk of thromboembolism in COVID-19 associated with high mortality. Further studies such as prospective collaborative international registries are helpful to decipher the pathophysiology and prognosis of stroke in COVID-19 to achieve the most effective care for this population to decrease mortality.

Declaration of Competing Interest

There is no conflict of interest of this study.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

None

Funding

None.

Footnotes

Publication history: This manuscript has not been published and is not under consideration elsewhere.

Financial Disclosures: Mai Yamakawa – reports no disclosures

Toshiki Kuno – reports no disclosures

Takahisa Mikami – reports no disclosures

Hisato Takagi – reports no disclosures

Gary Gronseth – reports no disclosures

Funding: There is no funding information for this article.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105288.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mao L., Jin H., Wang M. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:683–690. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sedaghat Z., Karimi N. Guillain Barre syndrome associated with COVID-19 infection: A case report. J Clin Neurosci Off J Neurosurg Soc Aust. 2020;76:233–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao H., Shen D., Zhou H., Liu J., Chen S. Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: causality or coincidence? Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:383–384. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30109-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toscano G., Palmerini F., Ravaglia S. Guillain-Barre Syndrome Associated with SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2574–2576. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camdessanche J.P., Morel J., Pozzetto B., Paul S., Tholance Y., Botelho-Nevers E. COVID-19 may induce Guillain-Barre syndrome. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2020;176:516–518. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alberti P., Beretta S., Piatti M. Guillain-Barre syndrome related to COVID-19 infection. Neurol(R) Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammation. 2020;7:e741. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padroni M., Mastrangelo V., Asioli G.M. Guillain-Barre syndrome following COVID-19: new infection, old complication? J Neurol. 2020;267:1877–1879. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09849-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Virani A., Rabold E., Hanson T. Guillain-Barre Syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. IDCases. 2020:e00771. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poyiadji N., Shahin G., Noujaim D., Stone M., Patel S., Griffith B. COVID-19-associated acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy: CT and MRI features. Radiology. 2020:201187. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lodigiani C., Iapichino G., Carenzo L. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klok F.A., Kruip M., van der Meer N.J.M. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19: An updated analysis. Thromb Res. 2020;191:148–150. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y., Xiao M., Zhang S. Coagulopathy and Antiphospholipid Antibodies in Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helms J., Tacquard C., Severac F. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1089–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oxley T.J., Mocco J., Majidi S. Large-Vessel Stroke as a Presenting Feature of Covid-19 in the Young. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avula A., Nalleballe K., Narula N. COVID-19 presenting as stroke. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoy D., Brooks P., Woolf A. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:934–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cantador E., Nunez A., Sobrino P. Incidence and consequences of systemic arterial thrombotic events in COVID-19 patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02176-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merkler A.E., Parikh N.S., Mir S. Risk of Ischemic Stroke in Patients with Covid-19 versus Patients with Influenza. JAMA Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2730. Published online July 2, (was preprint in medRxiv at the time of systematic review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romero-Sanchez C.M., Diaz-Maroto I., Fernandez-Diaz E. Neurologic manifestations in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: The ALBACOVID registry. Neurology. 2020;95:e1060–e1070. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yaghi S., Ishida K., Torres J. SARS2-CoV-2 and Stroke in a New York Healthcare System. Stroke. 2020;51:2002–2011. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030335. STROKEAHA120030335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beyrouti R., Adams M.E., Benjamin L. Characteristics of ischaemic stroke associated with COVID-19. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91:889–891. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Co C.O.C., Yu J.R.T., Laxamana L.C., David-Ona D.I.A. Intravenous Thrombolysis for Stroke in a COVID-19 Positive Filipino Patient, a Case Report. J Clin Neurosci Off J Neurosurg Soc Aust. 2020;77:234–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deliwala S., Abdulhamid S., Abusalih M.F., Al-Qasmi M.M., Bachuwa G. Encephalopathy as the sentinel sign of a cortical stroke in a patient infected with coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) Cureus. 2020;12:e8121. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez-Pinto T., Luna-Rodriguez A., Moreno-Estebanez A., Agirre-Beitia G., Rodriguez-Antiguedad A., Ruiz-Lopez M. Emergency room neurology in times of COVID-19: malignant ischaemic stroke and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:e35–e36. doi: 10.1111/ene.14286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gunasekaran K., Amoah K., Rajasurya V., Buscher M.G. Stroke in a young COVID -19 patient. QJM Mon J Assoc Phys. 2020;113:573–574. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morassi M., Bagatto D., Cobelli M. Stroke in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: case series. J Neurol. 2020;267:2185–2192. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09885-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moshayedi P., Ryan T.E., Mejia L.L.P., Nour M., Liebeskind D.S. Triage of Acute Ischemic Stroke in Confirmed COVID-19: Large Vessel Occlusion Associated With Coronavirus Infection. Front Neurol. 2020;11:353. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharifi-Razavi A., Karimi N., Zarvani A., Cheraghmakani H., Baghbanian S.M. Ischemic stroke associated with novel coronavirus 2019: a report of three cases. Int J Neurosci. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2020.1782902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tunc A., Unlubas Y., Alemdar M., Akyuz E. Coexistence of COVID-19 and acute ischemic stroke report of four cases. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;77:227–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valderrama E.V., Humbert K., Lord A., Frontera J., Yaghi S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection and ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2020;51:e124–e127. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030153. STROKEAHA120030153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang A., Mandigo G.K., Yim P.D., Meyers P.M., Lavine S.D. Stroke and mechanical thrombectomy in patients with COVID-19: technical observations and patient characteristics. J Neurointerventional Surg. 2020;12:648–653. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alay H., Can F.K., Gozgec E. Cerebral Infarction in an Elderly Patient with Coronavirus Disease. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;53 doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0307-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hossri S., Shadi M., Hamarsha Z., Schneider R., El-Sayegh D. Clinically significant anticardiolipin antibodies associated with COVID-19. J Crit Care. 2020;59:32–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malentacchi M., Gned D., Angelino V. Concomitant brain arterial and venous thrombosis in a COVID-19 patient. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:e38–e39. doi: 10.1111/ene.14380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radmanesh A., Raz E., Zan E., Derman A., Kaminetzky M. Brain Imaging Use and Findings in COVID-19: A Single Academic Center Experience in the Epicenter of Disease in the United States. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41:1179–1183. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Escalard S., Maier B., Redjem H. Treatment of acute ischemic stroke due to large vessel occlusion with COVID-19: Experience From Paris. Stroke. 2020;51:2540–2543. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030574. STROKEAHA120030574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kihira S., Schefflein J., Chung M. Incidental COVID-19 related lung apical findings on stroke CTA during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Neurointerventional Surg. 2020;12:669–672. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benjamin E.J., Blaha M.J., Chiuve S.E. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boehme A.K., Luna J., Kulick E.R., Kamel H., Elkind M.S.V. Influenza-like illness as a trigger for ischemic stroke. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5:456–463. doi: 10.1002/acn3.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elkind M.S., Carty C.L., O'Meara E.S. Hospitalization for infection and risk of acute ischemic stroke: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke. 2011;42:1851–1856. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.608588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smeeth L., Thomas S.L., Hall A.J., Hubbard R., Farrington P., Vallance P. Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke after acute infection or vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2611–2618. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McFadyen J.D., Stevens H., Peter K. The Emerging Threat of (Micro)Thrombosis in COVID-19 and Its Therapeutic Implications. Circ Res. 2020;127:571–587. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saver J.L. Cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:e26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1609156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lisabeth L.D., Brown D.L., Hughes R., Majersik J.J., Morgenstern L.B. Acute stroke symptoms: comparing women and men. Stroke. 2009;40:2031–2036. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.546812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Madsen T.E., Khoury J., Cadena R. Potentially Missed Diagnosis of Ischemic Stroke in the Emergency Department in the Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Study. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23:1128–1135. doi: 10.1111/acem.13029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lippi G., Cervellin G., Casagranda I., Morelli B., Testa S., Tripodi A. D-dimer testing for suspected venous thromboembolism in the emergency department. Consensus document of AcEMC, CISMEL, SIBioC, and SIMeL. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014;52:621–628. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2013-0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petrilli C.M., Jones S.A., Yang J. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1966. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Z.F., Su F., Lin X.J. Serum D-dimer changes and prognostic implication in 2009 novel influenza A(H1N1) Thromb Res. 2011;127:198–201. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davey R.T., Jr., Lynfield R., Dwyer D.E. The association between serum biomarkers and disease outcome in influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus infection: results of two international observational cohort studies. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sato T., Sato S., Yamagami H. D-dimer level and outcome of minor ischemic stroke with large vessel occlusion. J Neurol Sci. 2020;413 doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.116814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.You L.R., Tang M. The association of high D-dimer level with high risk of ischemic stroke in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients: A retrospective study. Med (Baltimore) 2018;97:e12622. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choi K.H., Seo W.K., Park M.S. Baseline D-Dimer Levels as a Risk Assessment Biomarker for Recurrent Stroke in Patients with Combined Atrial Fibrillation and Atherosclerosis. J Clin Med. 2019;8:1457. doi: 10.3390/jcm8091457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paranjpe I., Fuster V., Lala A. Association of Treatment Dose Anticoagulation With In-Hospital Survival Among Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:122–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dogra S., Jain R., Cao M. Hemorrhagic stroke and anticoagulation in COVID-19. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis Off J Natl Stroke Assoc. 2020;29 doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen T., Wu D., Chen H. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368:m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aggarwal G., Cheruiyot I., Aggarwal S. Association of Cardiovascular Disease With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Severity: A Meta-Analysis. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2020;45 doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2020.100617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.