Abstract

The COVID-19 health crisis has engendered a set of additional health and safety regulations and procedures (e.g. social distancing) to the hospitality industry. The purpose of this paper is to explore in-depth how organizations can facilitate employees’ deep compliance with these procedures. Employing an instrumental case-study approach, we collected multi-level interview data and archival data in a small-medium sized restaurant in China. The findings reveal that employees’ deep compliance with safety procedures includes a four-stage psychological process, and this process is underpinned by both management safety practices and organizational crisis strategies. As the hospitality industry starts to exit lockdown and ramp up operations, this study offers theoretical and practical insights on how organizations in hospitality can protect the health and safety of their employees and the broader community.

Keywords: COVID-19, Deep compliance, Management commitment to safety, Crisis strategy

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted the hospitality and tourism sectors around the globe, forcing widespread closures and strict requirements on trade due to the risk of infection and even death for some vulnerable segments of the community (Nicola et al., 2020; Rivera, 2020). Several factors are linked to why hospitality is highly susceptible to this kind of health-related crisis - high volume of patrons, large staff work teams, exposure to intra- and international travelers, the potential for contagion through cross-contamination, and multiple pathogen delivery mechanisms (e.g., surfaces, cutlery and crockery, food; Leung and Lam, 2004). As the world emerges from lockdown, hospitality remains a high-risk industry due to the threat of a ‘second wave’ (Xu and Li, 2020), and the organizations in this industry must learn how to conduct business, while remaining safe at the same time. Failure to comply with COVID-19 safety measures might endanger the health and safety of frontline staff, the viability of the business, and the general public.

This research is set out to understand how hospitality organizations might facilitate employee compliance with COVID-19 safety requirements and protocols in response to this unprecedented health crisis. However, safety research in hospitality mostly focused on food safety rather than employee safety, such as the factors influencing the implementation of food safety measures (e.g., Guchait et al., 2016; Harris et al., 2017). The existing hospitality crisis management literature, on the other hand, tends to focus more on organizational response practices in relation to marketing and organization maintenance (e.g., Israeli and Reichel, 2003; Israeli et al., 2011), without a specific focus on the health and wellbeing of employees. There were a few exceptions, where a few studies examined hotel and restaurants’ response to the Sudden Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003. These studies provided a vivid account of the susceptibility and ‘brittleness’ of the hospitality industry to health-related threats. While they also briefly discussed the safety measures put in place, such as the acquisition of protective equipment and the enforcement of environmental hygiene (e.g., Chien and Law, 2003; Tse et al., 2006), the descriptive nature of these studies means that we have little theoretical insight on how organizations could effectively respond to a global pandemic.

Therefore, we draw on broader organizational safety research to guide our research inquiry. Particularly, we follow the theoretical framework put forth by Hu and colleagues (Hu et al., 2020), which differentiates between ‘deep’ (mindful awareness and careful application of safety procedures) and ‘surface’ compliance (demonstrating compliance with minimal effort). Building on this work, we seek to explore the unique psychological mechanisms that lead to a deep approach to compliance, which we found evolved over the course of the pandemic in the studied restaurants. To further explain the contributing contextual factor of deep compliance, we propose that employees’ deep compliance is created under the influence of management safety practices, as well as the organization’s overarching crisis response strategies. In doing so, our study not only contributes to the theoretical building of deep compliance but also provides practical insights for managers in the hospitality industry to effectively respond to COVID-19 pandemic.

The paper begins by reviewing literature in safety compliance and safety research, followed by the method. The findings are discussed in line with the key constructs and relationships depicted in the conceptual model. Finally, theoretical and practical implications are provided.

2. Literature review

2.1. Safety research in the hospitality context

In the hospitality context, particularly restaurants, most safety research has focused on food handlers and food safety because restaurants have been labelled as one of the most frequent settings for foodborne illness outbreaks (Murphy et al., 2011). Given the importance of food safety, significant research attention has been allocated to the factors contributing to or inhibiting employees’ compliance with food safety. On the whole, there are three common threads in food safety research. The first thread focusses on external factors, such as mandatory food safety training and certification specified in Food Codes or local statutes (Murphy et al., 2011). The second thread of our research has taken the lens of organizations and identified a list of organizational factors that can facilitate food safety compliance, such as organizational support (Guchait et al., 2016), leadership styles (Lee et al., 2013), and organizational food safety climate (De Boeck et al., 2017). In comparison, drawing on motivational theory, the third thread of research highlights that organizational drivers alone are not enough to lead to food safety. Thus, this line of research has shifted focus to employees and examines how employees’ risk perception (Griffith et al., 2010) or motivation (Harris et al., 2017) shapes their food safety compliance. Notably, in Harris et al.’s (2017) research, they highlighted that when employees perceive intrinsic values of complying with safety procedures, they are more likely to follow food sanitation regulations.

Although the findings from these studies have advanced the knowledge of food handlers’ compliance behavior in terms of food safety, they have left a significant gap in another aspect of organization safety - employee safety, especially service employees who have close contact with customers. Safety literature has established that employee safety is important to organizations because it directly contributes to reductions in injuries and associated costs (Christian et al., 2009). In comparison, failing to establish employee safety may ruin the employee-organization relationship, tarnish the organization’s reputation, and in very serious cases, result in lawsuits and bankruptcy. In the context of COVID-19, except for managing food safety, it is critical and essential for organizations to closely monitor employee safety, because protecting employees from infection not only demonstrates the organization’s responsibility to help contain the spread of the virus, but also determines the survival of the organization during this crisis. When employees are infected, restaurants may end up in bankruptcy or foreclosure, as evident in extensive anecdotal evidence, showing that worldwide, many restaurants have temporarily or even permanently closed down after one or more employees tested positive for coronavirus. Therefore, it is essential to expand the scope of safety research in the hospitality context by examining how to promote employee safety across the organization.

2.2. Safety compliance

Safety compliance refers to core safety tasks individuals carry out to maintain workplace safety (Griffin and Neal, 2000). These include a set of behaviors that aim to meet an organization’s safety requirements, such as compliance with the organization’s safety rules and procedures, as well as wearing personal protective equipment. Griffin and Neal (2000) proposed that safety compliance is influenced by an individual’s safety knowledge, safety skills and safety motivation, which in turn are influenced by the organization’s safety climate. Recent research has focused on not only whether people comply with safety procedures, but how they comply with procedures. This line of research is motivated by the finding that employees might comply with safety procedures for the mere sake of compliance, such that compliance with safety procedures becomes a ritual or superficial exercise, without furthering the objective of working safely (Hopkins, 2006). Similarly, the recent study by Rae and Provan (2019) on the work of safety professionals also differentiated compliance activities into safety work (demonstrating compliance through audits and checklists) and the safety of work (risk reduction within the physical safety of work).

Building on these existing studies, Hu et al. (2020) reconceptualized safety compliance by forwarding the concepts of deep compliance and surface compliance to contrast different ways workers can comply with safety rules and procedures. Employees engage in deep compliance with the intention to maintain workplace safety, and invest the effort required for enacting risk management strategies expected to accomplish organizationally-desired safety outcomes. In contrast, employees engage in surface compliance with the intention to minimally meet organizational requirements and therefore direct their effort and attention towards demonstrating basic compliance. The differentiation between deep and surface compliance provides a new avenue for safety compliance research, particularly given the preliminary evidence, which indicates that whereas deep compliance can reduce accidents and injuries, surface compliance contributes to increased occurrence of adverse safety events (Hu et al., 2020).

In terms of situational factors contributing to safety compliance, previous safety reseach has provided preliminary eviduence that management commitment to safety can promote deep compliance (Hu et al., 2020). It suggests that when employees perceive that management are genuinely concerned about safety, they are more motivated to behave safely (Christian et al., 2009). The outbreak of COVID-19 has introduced a list of new safety rules and procedures in addition to existing procedures as discussed in the food safety literature (e.g., hygiene). A pressing question is how organizations could facilitate deep compliance with COVID-19 safety rules and procedures to protect workers from being infected and stop possible transmission during service encounters. Although management commitment to safety has been identified as an organizational factor that can drive deep compliance (e.g., Hu et al., 2020), little is known about the underlying psychological process, and how management can create perceptions of commitment to safety among employees. Also, the mechanism that catalyzes and activates deep compliance in the context of a global health crisis needs to be addressed further. In the following empirical section, we explore these questions in the context of a case study conducted with restaurants in China.

3. The present study

As the main aim of the study is to analyze how deep compliance with COVID-19 safety measures can be fostered in the hospitality industry, we adopt a case study approach to develop a rich and contextualized description of the focal phenomenon. We applied an instrumental case study for primary data collection and analysis (Eisenhardt, 1989). Specifically, with this research approach, we are able to provide an in-depth evaluation of an important topic (e.g., safety compliance in the hospitality industry) that has many questions waiting to be answered (e.g., how do workers comply, what encourages workers to comply). Also, this method enables researchers to delve into the internal processes behind the phenomenon of interest, and develop a rich understanding of the experience and responses of top managers and employees in terms of deep compliance throughout COVID-19.

Based on purposive sampling criteria (Patton, 1990), our case is a small-medium sized private restaurant group in northern China (to protect company anonymity, henceforth labeled “ABC”). In China, most restaurants have gradually reopened since April 2020 (Clay, 2020), while the rest of the world was still in the lockdown phase. The Chinese government has introduced strict COVID-19 health and safety requirements, and the experience of restaurants implementing these new measures may offer valuable insights for restaurants in other regions. We chose ABC because it has managed to survive COVID-19 without massive layoffs or restructuring, and was operating at full capacity at the time of the study. In response to COVID-19, ABC management implemented a number of new health and safety procedures and practices. Thus, the case firm provides us with a suitable avenue to examine employees’ deep compliance and management safety strategies and behaviors. Practically, the case firm allowed us to interview the owner, senior managers, team leaders, and frontline employees. This approach serves the benefit of providing greater richness to the single case and offers multiple perspectives in explaining the organization’s response to the focal phenomena, as well as helping to cross-validate the data. ABC has one full-service restaurant with around 100 employees and two fast-food stores with around 20 employees in each. The variety in sizes enables a comparison within the organization, adding more layers and richness to the data. We now turn to the details of our research method.

4. Methodology

4.1. Background of the case company

ABC was founded in 1999 and is located in north China. The full-service restaurant (henceforth “ABC-R”) is run by a general manager, but the owner still participates in strategy-level decisions. Its main business includes banquet service, fine-dining service, and a specialty hotpot. The annual revenue as of 2019 was about 13 million yuan ($2 million). Two fast-food stores (hereinafter “ABC-F1” and “ABC-F2”) were opened in 2010 and 2011 as a variation of the full-service restaurant, which has a good reputation in the local community with high-quality cheap eats. In terms of safety, the company has a relatively good safety record and a strong safety culture as reported by the management and employees. It has no major health and safety incidents since its opening. Due to COVID-19, ABC-R closed its business on 26 January 2020, while two fast-food stores closed on 24 January and 22 January 2020 respectively (See Appendix for a summary of the COVID-19 timeline).

4.2. Data collection

The primary data collection method of this research was in-depth semi-structured interviews with both employees and the management. The choice of this data collection approach enabled participants from different levels and roles to share their perceptions, thus providing a rich database for analysis. The number of employee participants being interviewed was determined by data saturation when no new themes emerged during iterative data analysis (Thomson, 2010). Specifically, a total of 14 interviews were conducted, including seven interviews with frontline employees, two interviews with line managers, four interviews with senior management, and one interview with the owner. To ensure the privacy, we discussed with the management team to ensure each participant was able to participant in a private manner. During the interview, employees participants were explicitly made aware of that the interviews are for research purpose only, and their responses would in no way impact the restaurants or themselves. All interviews were conducted by phone call or WeChat voice call during May 2020. The duration of the interviews was 30–60 min s. Interviews were conducted in Chinese, and they were digitally recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim to facilitate detailed analysis (Creswell and Creswell, 2017). No incentives were offered for participation. Background information about the informants, such as age, job title, education, and tenure, were also collected (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Detailed list of informants.

| Informants | Job title | Gender | Education level | Age range | Number of years working for ABC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Executive level | |||||

| 1 | Founder and owner | M | Secondary/high school | 45–59 | 21 |

| 2 | General manager (ABC-R) | M | Secondary/high school | 45–59 | 10 |

| 3 | Service manager(ABC-R) | F | Secondary/high school | 35–44 | 14 |

| 4 | Store manager (ABC-F1) | F | Secondary/high school | 35–44 | 3 |

| 5 | Store manager (ABC-F2) | F | Secondary/high school | 35–44 | 8 |

| Supervisory level | |||||

| 6 | Service leader (dining lobby, ABC-R) | F | Secondary/high school | 35–44 | 9 |

| 7 | Service leader (private dining room, ABC-R) | F | Secondary/high school | 35–44 | 8 |

| General level | |||||

| 8 | Reception attendant (ABC-R) | F | Secondary/high school | 25–34 | 2 |

| 9 | Service attendant (ABC-R) | F | Secondary/high school | 35–44 | 0.5 |

| 10 | Service attendant (ABC-R) | F | Secondary/high school | 35–44 | 2 |

| 11 | Cook (ABC-F1) | F | Less than secondary/high school | 45–59 | 1 |

| 12 | Service attendant (ABC-F1) | F | Secondary/high school | 45–59 | 9 |

| 13 | Service attendant (ABC-F2) | F | Less than secondary/high school | 25–34 | 4 |

| 14 | Service attendant (ABC-F2) | F | Less than secondary/high school | 35–44 | 3 |

Note: ABC-R refers to the full-service restaurant. ABC-F1 refers to fast-food store 1 and ABC-F2 refers to fast-food store 2.

Two separate interview protocols were designed to examine compliance with COVID-safety measures from management and employees, respectively. In both cases, the interviews start by providing informants with an overview of the research, such as the purpose, the expected length of the interviews, and the confidentiality and anonymity. The background information (e.g., age, tenure, position, role) was also collected in this stage.

The management protocol was divided into three sections. The informants were first asked about the timeline throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as its perceived impacts on the business. The second section focused on the implementation of specific safety and health measures and employee responses to newly implemented measures. The closing part included the perceived effectiveness of these measures.

In the employee protocol, we started with a timeline question and another question about concerns, specifically: “what was your biggest concern since the outbreak of COVID-19”. The second section focused on their experience with the new COVID-19 procedures. The third section included an additional question related to the improvements the organization would make and what measures they think should be preserved after COVID-19.

In addition to interviews, we also collected and reviewed archival data, including the company’s social media posts on WeChat official account and posts in their employees’ group chat. These supplementary materials provide us with additional information on their COVID-19 safety measures (Appendix) and enables us further to triangulate the data (Yin, 2014).

4.3. Data analysis

Thematic content analysis was employed to analyze the interview data (Creswell and Creswell, 2017). A combination of inductive and deductive approaches was used to guide the coding process. As specified by Yin (2014), the deductive approach used in a case study provides a starting point by analyzing and comparing with previously established theory and empirical findings. The inductive approach enables the researcher to have an open mind in identifying new patterns from data. Specifically, a three-step analytical process was undertaken. First, each interview transcript was read thoroughly for open coding. Then, themes and categories were identified by analyzing and comparing the responses of participants. At the final step, perspectives of the participants at different levels of the organization (i.e., management and employees) about coping measures were compared and contrasted. These comparisons, in turn, helped to validate the information obtained from each participant at different organizational levels, such as employees’ response to the measures introduced by the management. In particular, the data analysis process included three stages. In the initial stage, collected data were transcribed and translated; followed by the coding stage, where “Nodes” were created in by using NVivo 12 by the first and second author independently. Then, the codes were cross-checked by the research team. The validated information was then used for data interpretation and presentation stage, where the sub-themes were generated by categorizing and grouping the relevant codes.

5. Findings

To illustrate how deep compliance with COVID-19 safety measures can be fostered in the hospitality industry, we present our finding in three sections: 1) employee deep compliance 2) management COVID-19 safety practice and 3) organizational strategies in response to COVID-19.

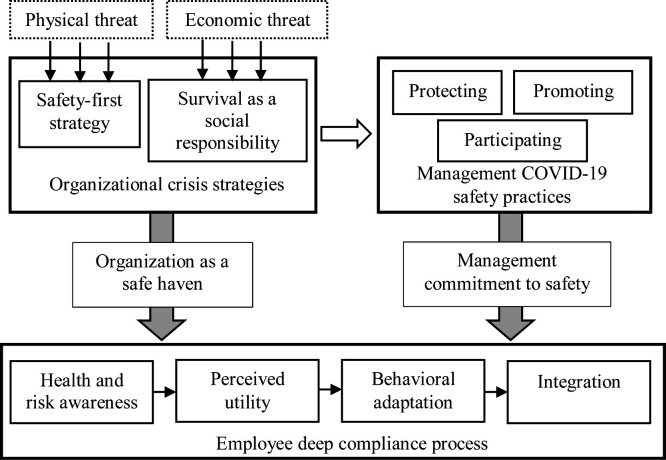

As depicted in Fig. 1 , our findings show that within individuals, employees experience deep compliance as a four-stage psychological process. Individuals’ engagement in deep compliance started with heightened risk and health awareness. Such awareness prompts perceived utility value of COVID-19 safety measures, which in turn motivate behavioral adaptation. Prolonged use then increases an individual’s confidence in the effectiveness of the new measures, prompting the integration of these measures into one’s work routine and safety practice.

Fig. 1.

Summary of deep compliance with COVID-19 safety measures.

This individual deep compliance process is heavily influenced and facilitated by three management-level COVID-19 safety practices: 1) prioritization of protection of the health and safety of employees, 2) relentless promotion of the importance of health and safety in the context of a pandemic, and 3) active participation in the newly established safety routines and activities. Through a combination of these management practices, management demonstrates a genuine commitment to workplace health and safety to employees.

Our finding further reveals that management safety practices and employees’ deep compliance are both embedded in and shaped by the broader organizational and environmental context. Particularly, we identified two salient environmental threats to the organization and its employees: the physical threat presented by COVID-19, as well as the economic impact on the hospitality industry, which threatens the viability of the organization and job insecurity for its employees. Under these threats, the organization responds by serving as a safe haven for the employees. In response to the physical threat, the organization adopted a safety-first strategy, putting other organizational priorities, including financial and operational goals to a second place. In response to the economic threat, the organization pivoted its core mission, emphasizing on the survival of the business as a social responsibility; that is, even though not financially viable, the organization opens in order to provide employment opportunities to its staff members. In doing so, the organization is able to meet the physical and job security needs of employees at the time of crisis, creating a solid relationship basis for cooperative safety responses from the workforce during a tough time.

5.1. Individual deep compliance

As depicted in Fig. 1, deep compliance consists of four stages: health and risk awareness, perceived utility, behavioral adaption, and integration.

5.1.1. Health and risk awareness

Increased health and risk awareness constitute the initial stage of the deep compliance process. As a few managers mentioned, increased health and safety awareness is the primary change since the outbreak of a pandemic. In our findings, it is evident that employees became more aware of the health threat of COVID-19 and showed a heightened sense of health and risk awareness, for example, “We are clear about the severity of this virus. In the restaurant industry, we get in contact with a lot of people; there is a huge customer flow, so we must be very cautious and raise our risk awareness.” Some believed the perceived risk extends to their family members: “I have other family members at home, after all, working at the restaurants we will be in touch with so many people, and when we go home, we are in close contact with our family members.”

5.1.2. Perceived utility

The heightened risk awareness phase further contributed to the perceived utility value of newly introduced COVID-19 safety measures. The utility value of safety procedures plays a major role in sustaining compliance behavior (Hu et al., 2018). Our findings reveal that growing considerations have been made to one’s own health and safety, as well as the health and safety of other organizational members and customers. As evidenced in the employee interviews, all of them confirmed the utility of the introduced safety measures. For example, when asked whether the new COVID-19 safety measures created extra work, one worker responded: “I won’t see them in this way. They are all essential and useful measures. The workload is not a big deal. This is for our own safety, and we also need to consider others, so we need to carry out these measures really well.”

Besides, many perceived that they have a moral or social responsibility to protect the health and safety of the customers who come to the restaurants. “True, they (COVID-safety measures) require more work. But it’s good for our customers, for everyone. We are all in this together. We need to understand each other. During a pandemic, I think being strict is good.”

Such responsibility is not only limited to reducing physical risk for the customers but also include the need to create a perception of safety for the customers. As a team leader acknowledged:

“The customers would see it as a good thing too. At least we are offering them certain protections. If someone who’s not feeling well comes in, it will make customers feel unsafe. We’ve had a customer who asked us: ‘Is it safe in your restaurant? Should I be worried?’ We can say to them, ‘you can be rest assured to dine in.’”

5.1.3. Behavioral adaptation

As workers comply with safety measures on a daily basis, many begin to become accustomed to them and adapt their behaviors accordingly. As one worker put it: “When we come to work, we are used to all safety measures. You make all the changes naturally. When we change into our uniform, the supervisors distribute the face masks, and we will put on the face masks without thinking. It is all about habit. We rarely forget them… Especially on handwashing, we have never seen this before. Now all staff members wash their hands really well before starting on the tasks. This is really necessary.”

Employees’ behavioral adaptation has been confirmed by the managers and team leaders who spoke very highly about how cooperative the workforce has been in complying with all new COVID-19 safety measures. “It’s basically 100 % for all the safety procedures, including cleaning the utensils, sanitization, the staff are doing really well.” This behavioral adaptation has also been observed during the period when the staff were stood down and were staying at home. As a manager commented, “Every day at 8 pm, they uploaded their travel history and temperature on time. No single one of them sent anything nonsense. They even took a picture of the thermometer. Very cooperative, no one is selfish.”

5.1.4. Integration

As staff members adapted their behaviors by complying with new COVID-19 safety measures, it became apparent that such adaptation leads to the final stage of deep compliance – integration with existing work routines. As one manager recalled, the pandemic really helped them to improve health and safety management in general. There is a shared consensus that many of the new safety measures should be in place regardless of whether there is a pandemic. Many have seen how these new measures directly contribute to other organizational priorities, including food safety, provision of high-quality customer service and fulfilment of responsibility to reduce the spread of transmissible diseases such as common cold and flu. Overall, with time, the managers and workers became more aware of the effectiveness and additional benefits of the new COVID-19 safety measures. Long-term maintenance of these measures and their integration into the existing safety management system is on the rise.

5.2. Management commitment to safety

Moving to the management level, our findings offered evidence of how managers demonstrate their commitment to safety, particularly during times of crisis. As an essential dimension of safety climate, management commitment to safety is the most influential predictor of employee safety behavior (Zohar and Polachek, 2014). Under the COVID-19 situation, we found that management commitment to safety is demonstrated by three management-level COVID-19 safety practices: protecting, promoting, and participating. Each of these practices is explained below.

5.2.1. Protecting

Protection reflects managers’ significant efforts in protecting their employees from being infected by coronavirus throughout the crisis. It involves the provision of safety resources, making important business decisions in response to safety concerns, as well as designing employee-oriented protective measures.

We documented that protection of staff members started with management’s provision of face masks before the lockdown of Wuhan. As one senior manager noted: “I came to know about the outbreak in Wuhan through my friend there. Though my city was not in lockdown just yet, I felt how horrible it could get. I then started to pile up the face masks and distribute them to all employees.”

As the local cases began to emerge, the owner made the decision to shut down the restaurants even before the government’s instruction to do so. He explained his rationale as below:

“It became serious at the time; we suddenly had more than a dozen of cases here. If there were confirmed cases in our restaurants, all staff members would be put on self-isolation. We don’t really have resources for that… We were trying to mitigate the risk, by deprioritizing financial considerations, but offering more safety for our staff. They need to go home. Because we are in the restaurant industry, people are coming from all different places, who knows we might have someone from Wuhan or other affected regions. We need to protect our staff.”

The decision was understood and appreciated by the frontline employees, “At the time when we began to panic, our restaurant had already decided to shut down temporarily. They (owner and managers) were concerned about our safety, so they shut down the business, let everyone go home and take a break.”

During the shutdown period, store managers constantly checked in on employees’ health through WeChat (a Chinese messaging app). As indicated by the managers, they set up a WeChat group, through which managers can send through self-protection advice to staff members and urge them to take a temperature check every day and stay alert to COVID-19 symptoms.

When the restaurants reopened, the management also implemented strict measures to protect the safety of staff members, including body temperature check for all working staff members, the cleaning and sanitation of all utensils and work surfaces (see Appendix for a full list of COVID-19 safety measures at ABC). The workers described those safety measures as comprehensive, capturing “all aspects” of work. As one worker described, she always feels “confident” in the restaurants: “Ever since I came here, I can see managers’ concern about employees, with good protective measures in place”.

Furthermore, the sense of protection seems to be prioritized over the organization’s business goals, with short-term gains deprioritized relative to long-term losses: “We do more than 100 % for our staff safety, as long as one customer show symptoms of coughing or high temperature, I will stop him/her from entering the store immediately. This is what I must do. I can’t afford to have one customer to influence my whole team.”

5.2.2. Promoting

Promoting includes management’s relentless efforts in emphasizing the importance of personal and work safety. As one senior manager acknowledged, health and safety can only be achieved when employees are interested and motivated to protect the safety of themselves and others. To achieve this goal, managers have introduced additional safety meetings that focus on self-protection awareness and communicate the expectations and safety performance standards. For example, one manager mentioned, “Before COVID-19, we only had pre-start meetings, but now we add two more post-shift meetings. In pre-start meetings, as a manager, I will communicate with staff about every aspect of COVID-19, such as the latest updates on confirmed cases, the newest health advice and requirements from health professionals or government, and the specific COVID-19 safety measures in the restaurants. In post-shift meetings, I will give a brief review on their safety performance, and point out the particular areas we need to pay more attention to, and more importantly, to tell them why we need to do so.”

In addition to daily meetings, a series of staff training on COVID-19 took place in this organization to inform staff about the pandemic. “We have held multiple training sessions for our staff. We talked about the current situation of the pandemic and the scientific ways to contain its spread at the workplace.”

Several employees recounted that their managers and supervisors often speak about self-protection and the protection of customers, during daily meetings, training, and even during staff lunch. “They (managers) always remind us to stay alert, to wear masks and to protect ourselves and others from the virus.” Similar to protection, constantly promoting the importance of safety by management has received positive feedback from the employees and increases their safety motivation.

5.2.3. Participating

Participation includes two specific aspects; one is a bottom-up approach where managers actively involve employees to work on COVID-19 related measures; the other is a top-down approach where managers regularly check and review employees’ compliance with COVID-19 safety practices.

To ensure the smooth implementation of COVID-19 safety measures, the managers actively participated in safety by working together with employees. One manager described how she worked with employees to develop the registration form required by government regulations:

“When the staff came to work, we prepared a register book to record their names, their family of origin, their travel history, and whether they have any COVID-19 symptoms. This book is a group idea.” She also mentioned how they came up with cleaning and sanitation practices: “Our staff members were sitting together, discussing how we do sanitization, how do we use the disinfectants, how do we use ethanol, etc. It’s all coming from our staff”. This is confirmed by one of the employee interviewees: “It was my idea on the ratio of disinfectant and ethanol, I saw that on TV, and I brought it to the store manager, and we used that”.

From our interviews, we can see that apart from the compulsory procedures, employees are welcome to participate in prevention work. Everybody could speak up or share their experiences. As long as it helps with containing the spread of the virus, any idea from the employees is encouraged and has been adopted.

In terms of the top-down approach, managers also participate in the safety routines by closely monitoring employees’ behaviors and conducting a safety check. “We do the checks every day, including random checks.” As one manager recounted, “the staff are doing a great job, we didn’t find any signs of poor safety job”. For employees who did not follow all protective measures, managers would give them constant reminders. As one employee shared, “It’s getting warm recently, sometimes we wear the mask a bit lower. Our manager will remind us to wear it properly. She is very strict”. As another employee echoed: “Particularly when it comes to facing customers, our leader will keep monitoring whether we wear masks”. Such safety checks are not constrained to the workplace, as one manager mentioned: “We also check whether they follow the self-protection measures during the commute to work and make sure those who take the bus take precaution. I check with them every day.”

From the perspective of employees, these random safety-checks are essential. For example, when asking about wearing a face mask, one worker commented that they were not bothered, because by having these checks, they feel their organization is genuinely concerned about their health and safety, which in turn alleviates their concerns and makes them feel safer at the workplace.

5.3. Organizational threats and strategies

5.3.1. The external threats

As specified in systems theory, organizations are not operating in a vacuum but shaped by various factors both internal and external (Katz and Kahn, 1978). In addition to the elements that are within the organization (e.g., management commitment), external elements (e.g., competition, technology disruption, and natural disasters) and the organization’s responses to these factors, are also important (Tse et al., 2006). Our findings show that the public health hazard of COVID-19 is one such external element, and it has placed dual threats on the organization and its employees. One threat is related to physical safety. Three interviewed employees explicitly expressed their concern and fear about contracting the virus. As discussed in the health and risk awareness section, they attribute such threat to the characteristic of hospitality work: during service encounters employees are in contact with a large number of customers on a daily basis, and anyone of them could carry the virus or touch a contaminated surface.

The management was also concerned about how the virus might threaten the viability of the business: “Everyone in China is super scared of this disease (i.e. COVID-19). If you do not take all the necessary protective measures, if there is a suspected case, or a real one, your store will be doomed. It will be shut down (by the government), and we may not be able to recover in a short period. We in the senior management team all think along these lines.”

Another major threat is related to the economic impact on the hospitality industry and job security. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, massive layoffs have begun in restaurants across the world (del Rio-Chanona et al., 2020). In the case firm, all managers and employees indicated that the industry had been hardest hit by this crisis, causing their ongoing anxiety over job security. The situation has further deteriorated as restaurant workers are generally depicted as low-skilled, temporary, and with a low entry barrier. Indeed, when we asked employees what their biggest concern since the outbreak of COVID-19 was, all of them ranked job insecurity as the primary concern, “I feel I need this job, I don’t have other hopes. I count on this job to make some money to maintain myself.”

Similarly, the management also understands how the hardship in the industry creates challenges for its employees: “The economy is tough out there, jobs are very hard to come by. They (the staff members) cherish the work opportunities provided here. This is a labor-intensive industry, with low requirements of education and qualification. They are all from low socio-economic background.”

5.3.2. Safety-first strategy

In response to the external threats, at the strategic level, the case firm has functioned as a safe haven for their employees by meeting their needs for physical safety and job security during the crisis.

Specifically, from the interview with the owner and senior management team, we found that they have adopted a safety-first strategy by placing an absolute priority on maintaining workplace health and safety during the pandemic, even at the cost of financial loss. For example, as mentioned above, the case restaurant was the first to voluntarily shut down in that region. Back then this is a tough decision, as it was Chinese New Year, the busiest time of the year for most restaurants to boost sales; however, the owner and senior management team decided to adopt the safety-first strategy by putting employees’ and customers’ safety ahead of business profits. As the owner explained,

“It’s all about safety, not the organization’s profit. As long as everyone is healthy and well, I will be happy. I think we have done a better job than what the government could imagine. No one complained about anything or expressed dissatisfaction. We are all getting through this together. When we decided to shut down, then all of the employees supported this decision.”

This is echoed by another senior manager: “Facing such an unprecedented pandemic, despite some safety measures meaning huge losses to the organization, we are still willing to do so, because only by fighting the pandemic together, can we get back to normal sooner. This is our responsibility as a business. Early on, we had to destroy a lot of raw food material (because we decide to shutdown)—a massive loss. But we still did it, and we believe this is the right thing to do. I’ve talked to employees about this, and they felt the same.”

It is the safety-first strategy that drives management to proactively take COVID-safe measures and safeguard employees’ physical health, promoting the importance of safety to its employees and actively participating in the daily safety routine.

5.3.3. Survival as a social responsibility

The second strategy is ‘survival as a social responsibility’. Recent research suggests that corporate social responsibility should also extend to internal stakeholders such as employees, to engage in activities that directly address employees’ personal and family needs that are above and beyond legal requirements (Hu and Jiang, 2018; Shen and Zhu, 2011). As highlighted by the owner, in front of this crisis, working to provide job security is one of the most important goals of his firm so that employees can keep their jobs and support their families during this difficult time. “Now to reopen is not financially viable, but for the sake of employees. We would be better off if we continue to shut down until the pandemic is over. However, while the organization would be safe in this way, our staff will be out of income and experience social instability. The livelihood of employees will be a huge issue. It’s more for taking social responsibility, not simply for the sake of the organization.” He further explained that as long as the restaurant can stay open and meet the payroll, he and investors are willing to take the financial losses.

The dedication of management to keep jobs for employees has contributed to positive and cooperative responses from employees, which serve as the foundation for complying with additional safety requirements, which create a significantly larger workload. As one manager put,

“In our organization, all staff members are able to keep their job. There are no pay cuts; all the benefits and rewards schemes remain the same. They are very appreciative that the business is willing to provide the same benefits and pay, even though the company is operating at a loss. They all appreciate that.”

The findings from employees provide support for the above senior manager’s statement. “As long as we get to keep the job, I am happy to do more for the restaurant. We are all in this difficult situation, the whole restaurant industry, because of the pandemic”.

We also found that for some employees, the relationship between the organization and the employee goes beyond transactional exchange, but has a deeper root in how employees perceive the organization as their family. As the manager recalled, “I think our employees love the restaurant as their own family, view their managers and co-workers as their extended family members. They tend to believe that if the restaurants need them to do this, they will do so and do it well. Because it’s a very special period of time, they become more compassionate. I have chatted with them many times, about the tough situation we are facing. And they all respond like ‘it is very hard for the business, we understand’. And I can tell they take greater ownership and try to contribute on their side.” This is echoed by several employees. For example:

“The business is tough now; we all should help. When it recovers, the organization will not forget us. We have worked here for so many years. We are like a family. The future will be brighter; now we just need to understand each other… I think I understand managers. Since I am here, I treat the restaurant as my family, and we all face this hardship together. If someone goes down, the whole family should be with them; it feels much better than facing this by yourself.”

6. Discussion and conclusion

As the world starts to reopen after the initial lockdown, hospitality organizations need to learn how to conduct business, while remaining safe at the same time. Although a number of new safety measures have been introduced, the extent to which these measures are complied with in a ‘deep’ or comprehensive manner will impact not only on the health and safety of hospitality employees but also the viability of the business. Drawing on a case study from China, this paper has sought to understand 1) what are the key psychological stages of deep compliance that employees have experienced, 2) what and how management safety practices can facilitate employees’ deep compliance, and 3) what and how the broader organizational and environmental context can further shape management safety practice and employees’ deep compliance. Based on the findings from the case study, we answered these questions by offering a framework of deep compliance, which integrates individual psychological stages, management practices, and organizational crisis strategies.

In relation to the first question, the findings show that individual employees experience deep compliance as a four-stage psychological process, starting with heightened risk and health awareness, and then moving to perceived utility value of COVID-19 safety measures and behavioral adaption, and ultimately promoting the integration of measures into the work routine. A key finding that emerged from this study is that the experience of deep compliance incorporates changes in employees’ awareness and perceptions, which drives motivation to apply the safety requirements and protocols. Furthermore, deep compliance is not static, but a continuous practice of safety behaviors which facilitates learning overtime, as employees further revise their perceptions of risks and safety procedures.

In relation to the second question, we found that managers can demonstrate their genuine commitment to workplace safety to employees through three management practices - protecting, promoting, and participating. In answering the question ‘what and how specific management practices can facilitate employees’ deep compliance in the context of COVID-19’, our research suggests that it is the combination of all three practices that cultivates an absolute commitment to employee safety and wellbeing, which then explicates the deep compliance process. Our research also suggests that the three practices seem to be more influential at different psychological stages. For example, protecting and promoting seems to be important for raising risk awareness and the utility value of safety procedures, whereas participating helps to translate those awareness perceptions into behavior and integration.

Finally, we uncovered that employees’ deep compliance, as well as management safety practices, are shaped by organizational crisis strategies. Particularly, we highlighted the two strategies that are particularly relevant: the safety-first strategy; and the survival of the business as a social responsibility strategy. Through these two strategies, the organization created a safe haven for employees during the times of crisis, creating a relationship basis for positive management and employee safety response to take place. Taken together, knowing how organizations can encourage staff’s safety compliance means managers and safety professionals can capitalize on the COVID-19 opportunity to drive more effective safety practices

6.1. Theoretical implications

Our study extends existing research on deep compliance by providing a deeper conceptualization of this concept as a four-stage psychological process. Deep compliance reflects an individual’s intention to achieve organizationally desired outcomes (i.e. safety), and the deployment of cognitive and physical resources to deliver this outcome (e.g. scanning for risks). Our findings extend this conceptualization by providing an enriched description of the deep compliance experience. We highlighted that increased awareness of health and safety risks underpin the intention of attaining safety goals. Our research also found that the motivation that drives deep compliance behavior goes beyond the protection of the safety of oneself and other organizational members, and incorporates a sense of moral responsibility for external stakeholders (i.e. customers) as well as the general public. Furthermore, Hu et al. (2020) assumed that deep compliance is always effortful as individuals invest cognitive and physical efforts to achieve safety goals. Our study added a time-perspective, suggesting that the experience of deep compliance might evolve from initial effortful experience to that of a less effortful and automatic work habit. Many expressed that they become used to the new routine after prolonged use: “No, it’s not a trouble at all” as one employee put it. The behavioral adaptation is eased by the fact that many of the new COVID-19 protection measures such as social distancing, hand washing and wearing face masks are common in non-work domains too, adding behavioral reinforcement. Furthermore, as employees comply with new COVID -19 measures, they develop a revised understanding of relevant workplace health and safety risks, and how the designed safety procedures and processes might protect them from potential harm. As a result, they become more confident about the effectiveness of these measures and are willing to continue with such practice even after the pandemic is over. Overall, our research advocates for a more longitudinal approach to understanding safety compliance.

Second, this study provides a vivid account of how management safety practices influence deep compliance process. We identified three managerial COVID-19 safety practices: namely protecting, promoting and participating. These practices map onto six behavioral dimensions of management commitment to safety proposed by Fruhen et al. (2019): communication, guidance and support, decision making and planning, allocating resources, involving workers, and participation. For example, the protecting practices include decision making based on safety concerns, as well as provision of safety resources. In relation to promoting practices, communication is an important means to promote the importance of safety via meetings and training sessions. In relation to participating practice, it includes top-down guidance and safety audits, as well as bottom-up involvement. In line with this line of research, we documented that employees perceive that their management is genuinely concerned about safety through these management COVID-19 safety practices. We further unveiled how these practices help raise employees’ health and safety awareness, influence the perceived utility value of the new COVID-19 safety measures, enforce compliance behaviors and the integration to existing safety practices. In doing so, our research advances the understanding of how management commitment to safety facilitates employee deep compliance.

Third, our findings suggest that an organization’s crisis response strategies are the ultimate driving force for both management safety practices as well as employee deep compliance. In response to the COVID-19 crisis, the case firm strives to protect its employees’ physical safety and job security. Informed by such crisis response strategies, organizational resources are allocated towards the development and implementation of new safety measures. Financial pressure is partially relieved via pay cuts at senior management level, while employee jobs and pay are largely intact. This crisis response strategy aligns with self-sacrifice leadership (De Cremer et al., 2009), which refers to “an abandonment or postponement of personal interests and privileges for the collective welfare” (Choi and Yoon, 2005, p. 52). Prior research suggests that self-sacrifice leadership is the most important antecedent of employee prosocial behavior, because the self-sacrificial leader operates as a role model motivating follower behavior. We extend this line of literature by suggesting that during the time of a crisis, leaders’ self-sacrifice, as well as concern for their employees, alleviate their concerns and distress resulting from uncertainty and threat due to COVID-19. In doing so, the organization becomes a safe haven for employees (Feeney, 2004), meeting their need for security. This, in turn, strengthens employees’ willingness to work with the organization and the motivation to participate in and comply with new safety measures.

In summary, our study suggests a need to adopt a multilevel and systemic perspective to understand how employee deep compliance can be created in an organization.

6.2. Managerial implications

Our findings bring several practical implications. First, our findings regarding the psychological processes implicated in deep compliance point to specific recommendations regarding the delivery of safety training. As most safety training includes a compliance component (Krauss et al., 2014), knowing more about the judgments and evaluations that underpin the transition from surface to deep compliance is invaluable. Specifically, our research shows that it may be advantageous to emphasize certain parts of the compliance process and highlight the utility and benefits of safety measures. Workers should also be given opportunities to learn how safety practices can become embedded in their everyday routines, reducing the impost and disruption to their daily tasks.

Second, our findings regarding management safety commitment provide practical suggestions about how a positive safety climate that promotes deep compliance can be achieved. Specifically, achieving deep compliance requires management to move beyond ideas founded on social exchange and towards more nuanced theories surrounding self-regulation, attachment, and intrinsic motivation. Particularly during pandemics or other disasters, where there might be a temptation to make quick and unilateral decisions, our research instead suggests that managers would be better served by slowing down decision making and including employees in the discussions. High-quality communication about the rationale and importance of safety measures also appears to be critical. During a pandemic, leaders should communicate openly and transparently about what they do and do not know, as well as share the ways in which safety is linked to production and long-term business viability during difficult times. Finally, visibly committing to the welfare, health, and wellbeing of employees through providing reassurance, allocating resources to safety procurement, and highlighting the priority of employee needs, helps to create a ‘safe haven’ within which employees feel safe and secure, bolstering their commitment to the organization and desire to deeply comply with safety measures.

Finally, our findings regarding organizational responses to the COVID-19 pandemic suggest that strategies convey signals to employees that can shape their relationships with the organization. Such a signaling effect could be stronger during the COVID-19 pandemic because it is an unprecedented event; organizational responses or strategies offer informative cues for employees to understand and make attributions about their organizations. As such, while organizations consider their strategies or responses to the COVID-19 pandemic based on economic and business-related factors, they should also consider the implications of those strategies or responses on employees’ understanding of the organizations and thus employee-organization relationships.

6.3. Limitations and future research orientation

The current study has several limitations. First, the researchers adopted a qualitative approach based on a single case study, which has limited generalization. The findings should be interpreted within this niche context. Although single case studies can serve as a powerful example (Siggelkow, 2007), in terms of having an in-depth understanding of safety compliance with contextualized findings, it is noted that future work in this area could simultaneously analyze multiple cases, considering the impact of COVID-19 on restaurants’ safety compliance can vary significantly. Notably, it would be interesting to have a comparative analysis of the safety culture and practices among different organizations. For example, to have case firms from the initial epicenter (i.e., Wuhan) may enrich our findings. Alternatively, future studies could seek to validate our findings using quantitative designs, with larger samples of firms.

Second, previous studies have suggested that there are strong cultural differences in organizations’ safety behaviors (e.g., Yorio et al., 2019). While this study gave important insight into the process and the triggers of deep compliance by focusing on an organization from China, as mentioned above, the generalizability of our findings outside this specific context is limited. Considering individuals in Chinese culture value power distance and collective responsibility, especially during the time of crisis (Yang, 1993), restaurant managers and employees in China may be different from those in other countries. For example, Liu et al. (2012) found that Chinese show a strong spirit of sacrifice in employment relations for the sake of the collective interest. Thus, when confronting a difficult time, Chinese people tend to display stronger solidarity and organizational loyalty. That is, the relationship between external threats and employee safety compliance behaviors may be stronger in Chinese firms than in Western firms. We, therefore, suggest that future studies verify and extend these findings in non-Chinese cultures.

Finally, COVID-19, as a public health crisis, has certain distinctive features when compared to other natural disaster crises (e.g., earthquake and hurricane). Its “during crisis” stage lasts much longer, and there is also intensive government “intervention” throughout the process. This feature means organizations’ experiences and responses could vary significantly over time. Therefore, future research would benefit from a longitudinal study that covers different stages of a crisis and captures organizations’ changes in regard to the level of threat perceived, the responses undertaken, and the results in terms of performance and safety.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Appendix A

See Table A1

Table A1.

COVID-19 Timeline.

| ABC-R | ABC-F1 | ABC-F2 | Government announcement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1.22 | Gave face mask to all employees | Closed for holiday as usual, planned to reopen on 1 February*. | ||

| 1.23 | Wuhan Lockdown Announced. | ||||

| 1.24 | Open as normal for Chinese New Year Eve banquets. | *Closed for holiday as usual, planned to reopen on 1 February | |||

| 1.25 | Open as normal. Customers called in to cancel their reservations. | ||||

| 1.26 | Temporarily closed | ||||

| 2.1 | Local government suggested cancel group dining service. | ||||

| 2.20 | Staged reopen for take-away only service | ||||

| 3.1 | Reopen for dine-in service | Local government lifted dine-in restrictions for fast-food stores | |||

| 3.17 | Local government lifted dine-in restrictions for full-service restaurant | ||||

| 3.18 | Reopen for dine-in service | ||||

| 3.29 | Reopen for dine-in service with ‘half-team’ rostered to work. | ||||

| 4.30 | All employees back to work with full work shifts. All services, except for large banquets, are back to normal. |

Notes: *employees at two fast-food stores have 7 days New Year leave, but due to the COVID-19, the return to work date was postponed.

Appendix B

See Table B1

Table B1.

COVID-19 Safety Measures and representative quotes.

| Measures | Supporting interview quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| Safety measures for employees | Before work,

|

“Our staff members take 4 temperature checks every day. If the temperature is above 37.5 °C, he/she will be required to take sick leave.” (Manager, ABC-R) |

During work,

|

“Before the shift, managers hand out face masks, and gloves. Mask is required. I have two face masks, one is for off-work personal use, and the other is provided by the manager for work use only.” (Employee, ABC-F1) | |

Off work,

|

“We have a WeChat group, called ‘We’re family’. During the lockdown period, we group chatted and reported temperature, and travel history in the group.” (Store manager, ABC-F1). | |

| Safety measures for customers | At the Entrance,

|

“Customers must wear a face mask before they enter our store, and at the entrance, we have a staff to scan Health QR code. If it is not green, we will not let him/her enter. For people who do not have Health Code, we will ask them to fill out an information form for contact tracing. We also have non-contact thermometer to check customers’ temperature.” (Employee, ABC-R) |

During the dining (ABC-R),

|

“In Chinese tradition, people prefer to share a meal with friends and family using their own chopsticks, but this may cause the spread of coronavirus. So, we provide ‘public chopsticks’, and experiment with serving separate portions rather than ‘family style’”(General manager, ABC-R) | |

During the dining (ABC-F1 and ABC-F2)

|

“We have lots of marks, such as the 1.5 distance marks on the floor, and the single direction arrow showing the entrance, exit, and the direction for collecting meal. If people stand too close, we will come over and remind them to keep social distance.” (Service attendant, ABC-F1) | |

After the dining,

|

“We ask clients to use WeChat for payment.” (Reception attendant, ABC-R) | |

| Other measures |

|

“We use ethanol for disinfection. We use such disinfection measures before, but now it becomes stricter. All tables and chairs will be cleaned using disinfectant spray, before customers taking the seats; and when they finish and leave the table, we will disinfect the table and chair again immediately.” (Store manager, ABC-F1). |

Appendix C

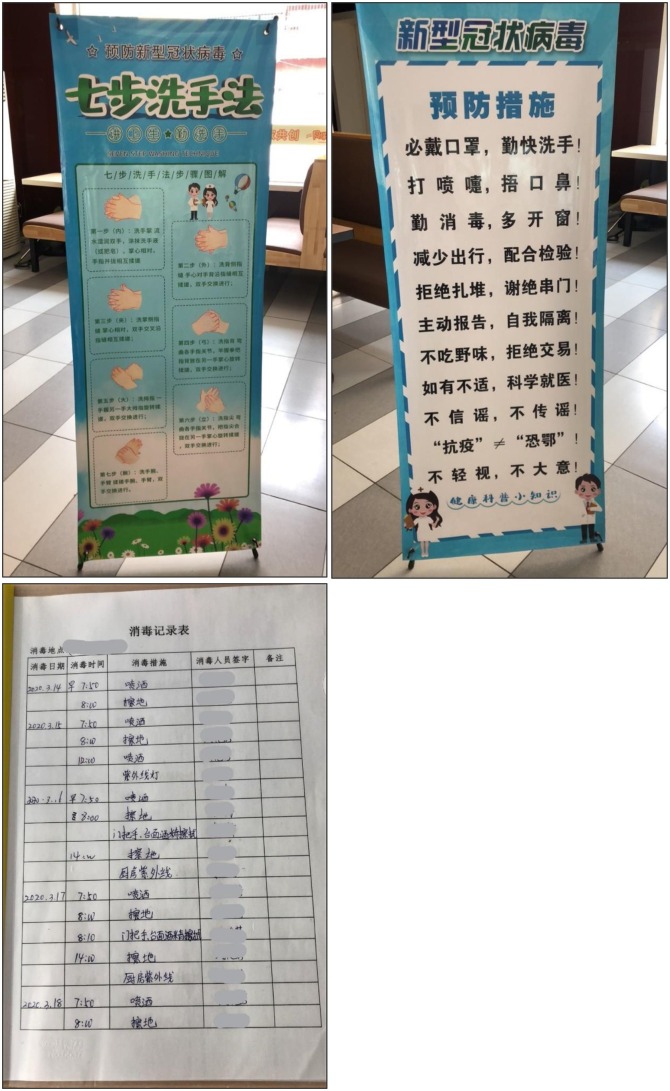

See Fig. C1

Fig. C1.

Pictures from top left to right. 7 steps hand washing poster; COVID-19 ‘stop spread’ sign; sanitation records with date, time, specific sanitation measures used, and signature.

References

- Chien G.C., Law R. The impact of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome on hotels: a case study of Hong Kong. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2003;22(3):327–332. doi: 10.1016/S0278-4319(03)00041-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y., Yoon J. Effects of leaders’ self-sacrificial behavior and competency on followers’ attribution of charismatic leadership among Americans and Koreans. Current Res. Soc. Psychol. 2005;11(5):51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Christian M.S., Bradley J.C., Wallace J.C., Burke M.J. Workplace safety: a meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009;94(5):1103. doi: 10.1037/a0016172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay X. The Telegraph; 2020. As Restaurants in China Start to Reopen, Could They Be a Recovery Roadmap for British Chefs?https://www.telegraph.co.uk/food-and-drink/features/restaurants-china-start-reopen-could-recovery-roadmap-british/ April. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J.W., Creswell J.D. Sage publications; 2017. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. [Google Scholar]

- De Boeck E., Mortier A.V., Jacxsens L., Dequidt L., Vlerick P. Towards an extended food safety culture model: Studying the moderating role of burnout and jobstress, the mediating role of food safety knowledge and motivation in the relation between food safety climate and food safety behavior. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017;62:202–214. [Google Scholar]

- De Cremer D., Mayer D.M., van Dijke M., Schouten B.C., Bardes M. When does self-sacrificial leadership motivate prosocial behavior? It depends on followers’ prevention focus. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009;94:887–899. doi: 10.1037/a0014782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Rio-Chanona R.M., Mealy P., Pichler A., Lafond F., Farmer D. Supply and demand shocks in the COVID-19 pandemic: an industry and occupation perspective. Covid Econ. 2020;6:65–103. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989;14(4):532–550. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney B.C. A secure base: responsive support of goal strivings and exploration in adult intimate relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004;87(5):631. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruhen L.S., Griffin M.A., Andrei D.M. What does safety commitment mean to leaders? A multi-method investigation. J. Safety Res. 2019;68:203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2018.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin M.A., Neal A. Perceptions of safety at work: a framework for linking safety climate to safety performance, knowledge, and motivation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000;5(3):347. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith C.J., Livesey K.M., Clayton D. The assessment of food safety culture. Br. Food J. 2010;112(4):439–456. [Google Scholar]

- Guchait P., Neal J.A., Simons T. Reducing food safety errors in the United States: leader behavioral integrity for food safety, error reporting, and error management. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016;59:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Harris K.J., Murphy K.S., DiPietro R.B., Line N.D. The antecedents and outcomes of food safety motivators for restaurant workers: an expectancy framework. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017;63:53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins A. Studying organizational cultures and their effects on safety. Saf. Sci. 2006;44(10):875–889. [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Jiang Z. Employee-oriented HRM and voice behavior: a moderated mediation model of moral identity and trust in management. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018;29(5):746–771. [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Griffin M., Yeo G., Kanse L., Hodkiewicz M., Parkes K. A new look at compliance with work procedures: an engagement perspective. Saf. Sci. 2018;105:46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Casey T., Griffin M. You can have your cake and eat it too: embracing paradox of safety as source of progress in safety science. Saf. Sci. 2020;130 [Google Scholar]

- Israeli A.A., Mohsin A., Kumar B. Hospitality crisis management practices: the case of Indian luxury hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011;30(2):367–374. [Google Scholar]

- Israeli Aviad, Reichel Arie. Hospitality crisis management practices: the Israeli case. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2003;22(4):353–372. [Google Scholar]

- Katz D., Kahn R.L. Vol. 2. Wiley; New York: 1978. p. 528. (The Social Psychology of Organizations). [Google Scholar]

- Krauss A., Casey T., Chen P.Y. Contemporary Occupational Health Psychology; 2014. Making Safety Training Stick; pp. 181–197. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.E., Almanza B.A., Jang S.S., Nelson D.C., Ghiselli R.F. Does transformational leadership style influence employees’ attitudes toward food safety practices? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013;33:282–293. [Google Scholar]

- Leung P., Lam T. Crisis management during the SARS threat: a case study of the Metropole Hotel in Hong Kong. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2004;3(1):47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Hui C., Lee C., Chen Z.X. Fulfilling obligations: why Chinese employees stay. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012;23(1):35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K.S., DiPietro R.B., Kock G., Lee J.S. Does mandatory food safety training and certification for restaurant employees improve inspection outcomes? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011;30(1):150–156. [Google Scholar]

- Nicola M., Alsafi Z., Sohrabi C., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A., Iosifidis C., et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int. J. Surg. 2020:78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M.Q. SAGE Publications, Inc; 1990. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Rae A., Provan D. Safety work versus the safety of work. Saf. Sci. 2019;111:119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera M. Hitting the reset button for hospitality research in times of crisis: COVID-19 and beyond. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Zhu C.J. Effects of socially responsible human resource management on employee organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011;22:3020–3035. [Google Scholar]

- Siggelkow N. Persuasion with case studies. Acad. Manag. J. 2007;50(1):20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson S.B. Grounded theory-sample size. J. Adm. Gov. 2010;5(1):45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Tse A.C.B., So S., Sin L. Crisis management and recovery: how restaurants in Hong Kong responded to SARS. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2006;25(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S., Li Y. Beware of the second wave of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10233):1321–1322. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30845-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K.S. Chinese social orientation: an integrative analysis. In: Cheng L.Y., Cheung F.M.C., Chen C.-N., editors. Psychotherapy for the Chinese: Selected Papers from the First International Conference; Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Yin R.K. 5th ed. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2014. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Yorio P.L., Edwards J., Hoeneveld D. Safety culture across cultures. Saf. Sci. 2019;120:402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2019.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohar D., Polachek T. Discourse-based intervention for modifying supervisory communication as leverage for safety climate and performance improvement: a randomized field study. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014;99(1):113. doi: 10.1037/a0034096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]