Abstract

Background:

Globally, road traffic injuries (RTIs) are a leading cause of disability and trauma-related deaths. We aimed to describe the clinical and epidemiological characteristics and outcomes of RTIs in our environment to provide the evidence for effective control measures.

Methods:

This was a 1-year retrospective study of all patients with RTIs treated at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu, Nigeria.

Results:

Four hundred and twenty-one patients with 484 injuries were studied. The mean age of the patients was 34.4 ± 14.6 years, and the male-to-female ratio was 3.3:1. Most of the injuries occurred on intercity roads/highways (48.7%) and involved motorcycle crashes (31%). Soft-tissue injuries (27.7%) and fractures (21.9%) were the most common types of injuries. The lower extremities were the most common sites of injury. The mean injury-arrival interval was 23.2 ± 2.4 h. The injury severity score (ISS) ranged from 1 to 50, with a mean of 9.2 ± 2.9. The 1-year mortality rate was 10.7%. Traumatic brain injury, open vehicular injuries, and increased ISS were the potential risk factors for mortality.

Conclusion:

Soft-tissue injuries and fractures were the most common types of injuries. The majority of the injuries occurred on the inter-city roads and highways and involved head-on-collisions with motorcycles. The young male adults were the most commonly affected age group.

Key Words: Characteristics, epidemiology, Nigeria, outcomes, road traffic injuries

INTRODUCTION

Injuries are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in both developing and developed countries. About 5.8 million people die each year as a result of injuries, and this constitutes 16% of the global burden of diseases and 10% of the world's deaths.[1,2] Overall, injuries are estimated to be the third most common cause of death globally.[3] Road traffic injuries (RTIs) are a leading cause of premature death and disability worldwide.[4] They are currently ranked 9th globally among the leading causes of disease burden in terms of disability-adjusted life years lost.[5] An estimated 1.24 million lives are lost annually from RTIs globally. It is estimated that by the year 2020, RTIs will have moved from the 9th to 3rd position in the global disease burden ranking and the economic loss from road traffic crashes is estimated at United States Dollars 518 billion per annum.[6]

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are thought to bear more than 85% of the global burden of deaths and injuries arising from road traffic crashes.[7] This may be attributable to accelerated urbanization and motorization of many developing countries with poor road infrastructure, inefficient trauma systems, and poor enforcement of traffic laws. In Nigeria, RTIs have been identified as a major public health problem, but there are no pragmatic approaches to combat this problem.[8,9] Previous studies have reported that RTIs are a leading cause of trauma-related deaths and the most common cause of disability.[8,9,10,11] This has enormous physical, social, emotional, and economic implications on the society. For effective control measures to be developed, the data generated systematically from the epidemiological studies are needed.

Despite the burden of RTIs in Nigeria, the most populous country in Africa, documentation of the injury characteristics, associated factors, and outcomes of RTIs in this region have been inadequate. This study was designed to answer the question: What are the characteristics and determinants of outcome of RTIs in our environment? The objectives of this study were to describe the epidemiological characteristics, the pattern, and outcomes of treatment of RTIs in our hospital. The result of this study will help in developing effective intervention measures against this public health problem not only in Nigeria but also in other LMICs with similar road infrastructure and trauma systems.

METHODS

Study design and setting

This was a 1-year retrospective, hospital-based study conducted at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital (UNTH) Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu, Nigeria. The medical records of all the patients who sustained injuries from road traffic crashes and were treated at our hospital from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2015, were reviewed.

The hospital is a 500-bed tertiary hospital and a major referral trauma center in the south-eastern region of Nigeria. It is located along a very busy expressway and serves the states of southeast, south-south, and north-central regions of Nigeria with a population of about 5 million people. This study was conducted according to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines for reporting observational studies.

Ethics approval

The research and ethics committee of UNTH Ituku-Ozalla approved the study protocol before the study commenced.

Study population and data collection

The study population included all road traffic crash victims who were treated in our hospital from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2015. The medical records of all the patients who presented with RTIs within the study period were retrospectively assessed. Patients who had incomplete medical records were excluded from the study. Data were extracted from the medical records of the patients and entered into a data collection form designed for this study. The demographic data of the patients, type of vehicle, type of road, mechanism of road crash, anatomical site of the injury, type of injury, injury-arrival interval, injury severity score (ISS), monthly distribution of injuries, length of hospital stay, and outcome of the treatment were retrieved from the medical records. The follow-up records of the patients for a period of at least 1 year after the discharge were recorded. The outcome measures used were full recovery from injuries within 1 year of treatment; the presence of disability arising from the injuries within 1 year of treatment and death within 1 year.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 22.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago IL, USA). Associations between two or more qualitative variables were assessed using the Chi-square test of significance. The frequency of variables was identified using descriptive statistics and described using frequency distribution. The patterns and relationships between several variables were analyzed using the multivariate analysis (logistic regression). A two-sided P << 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

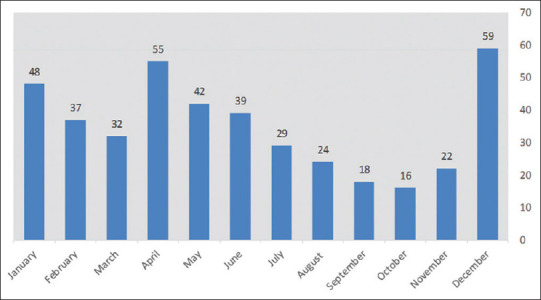

Four hundred and twenty-one patients with 484 injuries were studied. Sixteen patients were excluded from the study because of incomplete medical records. During the study period, a total of 6238 patients presented to the accident and emergency unit. Thus, the proportion of RTIs in this study is approximately 67 in 1000. Their ages ranged from 6 months to 78 years, with a mean of 34.4 ± 14.6 years. Most patients were between the age group of 21 and 40 years (235 [55.8%]). The modal age group was 31–40 years. There were 323 males and 98 females, with a male: female ratio of 3.3:1. Majority (48.7%) of the injuries occurred on intercity roads/highways [Table 1]. The months that witnessed peak injury incidence were January (48 [11.5%]), April (55 [13.6%]), and December (59 [13.9%]) [Figure 1].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the patients (n=421)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| <1 | 4 (0.9) |

| 1-10 | 29 (6.9) |

| 11-20 | 25 (5.9) |

| 21-30 | 107 (25.4) |

| 31-40 | 128 (30.4) |

| 41-50 | 58 (13.8) |

| 51-60 | 40 (9.5) |

| 61-70 | 18 (4.3) |

| 71-80 | 12 (2.8) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 98 (23.3) |

| Male | 323 (76.7) |

| Occupation | |

| Drivers/motorcyclists | 106 (25.1) |

| Farmers | 21 (4.9) |

| Students/pupils | 51 (12.2) |

| Civil servants | 67 (16) |

| Unemployed | 23 (5.6) |

| Business/traders | 93 (22) |

| Artisans | 59 (13.9) |

| Others | 1 (0.3) |

| Types of roads | |

| Intracity | 128 (30.4) |

| Intercity/highways | 205 (48.7) |

| Rural | 88 (20.9) |

Figure 1.

Distribution of road traffic injuries by months of the year

Motorcycle crashes (131 [31%]) were responsible for the majority of the RTIs, followed by crashes involving minibuses (116 [27.5%]) and cars (88 [21%]) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Types of vehicles involved in road traffic injuries

| Types of vehicles | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Motorcycle | 131 (31) |

| Minibus | 116 (27.5) |

| Car | 88 (21) |

| Tricycle | 25 (5.9) |

| Lorry | 16 (38) |

| Pedestrian | 45 (10.8) |

| Total | 421 (100) |

Riders of motorcycles and vehicle drivers (195 [46.3%]) accounted for majority of the victims, followed by passengers (181 [42.9%]) and pedestrians (45 [10.8%]). The majority of motorcycle crash victims were riders (86 [65.6%]), whereas passengers and pedestrians constituted 59.8% and 45.7% of motor vehicular crash victims, respectively. Seatbelt and helmet use was recorded in 29.2% and 10.8% of occupants of vehicles and motorcyclists, respectively. Head-on-collision (165 [39.2%]) was the most common mechanism of the accident followed by vehicle somersault (70 [16.6%]). Other mechanisms of the accident are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mechanisms of road traffic crashes

| Mechanism of road crash | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Head-on-collision | 165 (39.2) |

| Somersaulting | 69 (16.4) |

| Side collision | 70 (16.6) |

| Veering off road | 30 (7.1) |

| Pedestrian | 45 (10.7) |

| Not stated | 42 (10) |

| Total | 421 (100) |

Sixty patients (14.3%) sustained multiple injuries. Soft-tissue injuries (134, 27.7%) were the most common type of injuries followed by fractures (106 [21.9%]) and traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) (97 [20%]), as shown in Table 4. The ISS of the patients ranged from 1 to 50, with a mean score of 9.2 ± 2.9. The major injury was defined as ISS >15. Majority of the patients (253 [60.1%]) had ISS >15.

Table 4.

Types of injuries

| Injuries | n (%) |

|---|---|

| TBIs | 97 (20) |

| Fractures | 106 (21.9) |

| Dislocations | 26 (5.4) |

| Soft-tissue injuries | 134 (27.7) |

| Blunt chest injuries | 47 (9.7) |

| Blunt abdominal injuries | 24 (4.9) |

| Burns | 9 (1.9) |

| Spinal injuries | 29 (6.0) |

| Crush injuries | 12 (2.5) |

| Total | 484 (100) |

TBIs: Traumatic brain injuries

The injury-arrival interval ranged from 15 min to 1 week with a mean interval of 23.2 ± 2.4 h. Only 30 patients (7.1%) presented to the emergency department within the “golden hour,” 118 (28%) presented within the first 6 h, whereas 273 (64.8%) presented after 6 h of the injury.

TBI was associated more with motorcycle crashes in which the riders and passengers did not wear helmets than in the crashes where the riders and passengers wore helmets (χ2= 31.99; P = 0.001). Motorcycle crashes injuries that occurred along intercity roads and highways were multiple in nature and associated with higher ISS (χ2= 13.32; P = 0.024). Patients who had been involved in motorcycle crashes as well as pedestrians (open vehicle injuries) were more likely to sustain severe injuries compared to the drivers and passengers of cars and minibuses (closed vehicle injuries) (χ2= 14.90; P = 0.012). Drivers and passengers of cars and minibuses who wore seatbelt had significantly lower ISS and mortality rates compared to those who did not wear seatbelt (χ2= 35.41; P = 0.0001). The majority of the injuries occurred in the lower extremities (124 [25.6%]) which were mostly associated with motorcycle crashes (χ2= 33.51; P = 0.001). Head/neck and upper extremities were the anatomical sites of injuries in 22.7% and 22.1% of victims, respectively [Table 5].

Table 5.

Anatomical site of injuries

| Distribution of injuries by body region | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Head/neck | 110 (22.7) |

| Upper extremity | 107 (22.1) |

| Chest | 60 (12.4) |

| Abdomen | 54 (11.2) |

| Spine | 29 (6.0) |

| Lower extremity | 124 (25.6) |

| Total | 484 (100) |

The mean length of the hospital stay was 14.5 ± 8.2 days, with a range of 1–252 days. Two hundred and seventy-one (64.3%) patients were treated and discharged home without any disability; 26 patients (6.2%) were treated and discharged home with permanent disabilities (loss of body parts, hemiplegia, paraplegia, etc.); 12 (2.9%) were referred to other hospitals on request; and 67 (15.9%) left against medical advice. Discharged against medical advice was associated with victims who sustained fractures (χ2= 39.83; P = 0001). After a 1-year follow-up period, mortality was reported in 45 patients giving a 1-year mortality rate of 10.7%. Analysis of the potential risk factors for death showed that patients with increased ISS, TBI, and open vehicle injuries were found to be more vulnerable (χ2= 12.63; P = 0.032).

DISCUSSION

The incidence of RTIs in this study was 6.7% (67 in 1000 population). This figure is comparable to the incidence of RTI of 41 in 1000 population reported by Laninjo et al.[9] about 9 years earlier. It also suggests a possible increase in the incidence of RTI in Nigeria. This poses a major public health problem in Nigeria with huge economic losses. It calls for the urgent attention of all stakeholders in both government and nongovernmental agencies to address this significant cause of morbidity and mortality in Nigeria.

Majority of the victims of road traffic crashes were males. The most common age group involved was 21–40 years. These findings are similar to other studies in Nigeria and other parts of the world.[3,12,13] The young adult males are most commonly involved in trauma because they are the active age group of the society. They are most commonly involved in social and economic activities. Their tendency to risky behaviors also put them at the risk of RTIs. The man-hours lost, the morbidity and mortality from RTIs in this economically productive population, has a huge negative impact on the economy of the nation.

Most road traffic crashes occurred on intercity roads and highways, whereas a significant proportion (20.9%) occurred on rural roads. This is different from a World Health Organization study in Europe where about 67% of injuries occurred on urban (intracity) roads.[14] This disparity may be attributed to the location of our hospital which is along a major highway and surrounded by many rural communities.

This study noted a seasonal pattern in the incidence of road traffic crashes. The months of January, April, and December witnessed the increased incidence of road traffic crashes. Other studies in Nigeria by Akinpelu et al.[10] in Ile Ife, Ohakwe et al.[15] in Owerri, and Eke et al.[16] in Port-Harcourt have also reported seasonal patterns in the incidence of road traffic crashes. The pattern of RTIs in this study is similar to the study by Ohakwe et al.[15] who also noted the peak incidence in January and December. In contrast, Eke et al.[16] reported that most road traffic crashes occurred between July and August, whereas Akinpelu et al.[10] recorded the highest incidence in April, July, and September.

Our findings may be explained by the fact that December/January and April are the festive periods in Nigeria. While Christmas and New Year celebrations take place in December and January, respectively, the Easter celebration usually holds in April. These festivals are usually associated with heavy traffic on Nigerian roads as people travel from one location to the other. In addition, these seasons coincide with school holiday periods when school children are out-of-school and may be more prone to RTIs on the streets.

In this study, road traffic crashes involving motorcycles and commercial buses were the leading causes of injuries. This is similar to the reports in previous studies by Madubueze et al.[12] and Boniface et al.[13] Motorcycles and minibuses are the common means of transportation in our environment. Mini-buses are commonly used on intracity and intercity roads, whereas the motorcycles are more commonly used in the intracity and rural roads. Drivers of vehicles and riders of motorcycles and tricycles accounted for majority of the victims, with riders of motorcycles contributing most to this number. The vulnerability of motorcycle riders has also been reported in previous studies.[12,17] This may be explained by the observation in this study that head-on-collision was the most common mechanism of injury, thereby making the drivers and riders more vulnerable to injuries. The drivers of commercial buses and riders of motorcycles should be educated on standard safety measures that must be observed for commercial transportation.

The usage of helmets among motorcycle crash victims in this study was very low. This is similar to the reports by a study in Bangladesh that reported a helmet usage rate of 17.8%,[18] but in contrast to other studies from Tanzania[13] and India[19] that reported higher helmet usage rates 43.4% and 64.3%, respectively. It was observed that TBI was positively associated with motorcycle crashes in which the riders and passengers did not wear helmets. There is poor enforcement of the use of helmets by riders and passengers of motorcycles in Nigeria and other developing countries. Seatbelt usage was also low and similar to a compliance rate of 27.3% reported in a previous Nigerian study.[20] This study also demonstrated that the use of seatbelts was associated with a significant reduction in the severity of injuries and mortality rates. The poor compliance with the use of helmets and seatbelts among victims of road traffic crashes is worrisome and calls for intensive public enlightenment, appropriate legislation, and strict enforcement of the use of safety devices by road users in Nigeria and other developing countries. These findings support the public campaigns for the use of helmets and seatbelts to remedy the public health problems of road traffic crashes.

Collisions were the most common mechanism of accidents (235 [55.8%]). Head-on-collision was the most common type of collision (165 [39.2%]). This is similar to the study by Madubueze et al.[12] in Abakaliki, Nigeria, where head-on-collisions accounted for 38.8% of the accidents. However, Pathak et al.[19] in India reported side collisions as the most common cause of accident in their study. Most of the mechanisms of the accidents such as collisions, summersaulting of vehicles, and vehicles veering off the roads are usually associated with over speeding. Bad roads which are prevalent in many developing countries may also cause the vehicles to veer off the roads as the drivers swerve to avoid potholes on the roads. Enforcement of speed limits and proper road maintenance may help to reduce the incidence of road traffic crashes in our environment.

Soft-tissue injuries and fractures were the most common types of injuries in this study and correlate with previous studies.[12] However, Akinpelu et al.[10] in Ile Ife Nigeria reported the head injury as the most common type of injury in their study. This may be explained by the high incidence of pedestrian injuries (23.7%) in their study. Injuries from motorcycle crash and pedestrian injuries (open vehicle injuries) were more severe than injuries from car and minibus crashes (closed vehicle injuries). This may be due to the exposure of the riders and passengers of motorcycles and pedestrians to the direct impact of the crashes. Injuries that occurred along the highways and intercity roads were also significantly more severe. This is in concurrence with the studies by Pathak et al.[19] and Lin et al.[21] who reported a significant association between the speed of travel and the severity of injury. The lower extremity was the most common injury site in this study. This correlated with an Indian study,[19] but in contrast with another Nigerian study[12] where the head was the most common site of injury and an Iranian study[22] where the upper limb was the most common site of injury. Lower extremity injuries were significantly associated with motorcycle crashes as has been reported in previous studies.[10,13,19] The exposure of the lower extremities of motorcycle riders to the direct impact of crashes, the relative instability of the motorcycle, and the tendency of motorcycle riders to over speed may explain this observation.

The mean injury-arrival time in our study was 23.2 h. This is significantly longer than 36.3 min reported by Newgard et al.[23] in a North American cohort study may be an indicator of the poor prehospital care of injured patients in our environment. The widespread patronage of traditional bonesetters has been postulated as an explanation for this observation.[24] The intervention of traditional bonesetters in the treatment of acute major trauma has been reported to be deleterious.[25,26]

Majority of the patients were treated and discharged home. However, a large number of patients, particularly those with long bone fractures left against medical advice. This is a common practice in our environment and has been reported in a previous study.[27] Many of these patients patronize traditional bonesetters who are believed to offer cheaper services and are culturally more acceptable in our environment. Increasing the coverage and scope of the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) will reduce out-of-pocket medical expenditure and increase access to health care.

The mortality rate in this study was 10.7% which is higher than 4.7%[12] and 6.8%[10] reported in previous studies. This disparity may be due to the differences in the characteristic of the injuries and efficiency of trauma care management in the different study locations.

Limitations of the study

This study was conducted at a single hospital site over a 1-year period and may not reflect the true picture of the problem and may make the results not generalizable. The retrospective and single-site design of the study might have limited the scope of the study. We recommend a multi-center prospective study that will increase the scope and generalizability of the results. There is also a possibility of selection bias in this study. The more severely injured patients may have died before arrival at the hospital, whereas the less severely injured patients may not have been admitted to the hospital.

CONCLUSION

Injuries arising from road transportation remain a major public health problem in our environment. This study provides valuable insight into the pattern and characteristics of RTIs prevalent in Nigeria. The young male adults are most vulnerable to RTIs with consequent economic losses. The use of motorcycles as a means of transportation is dangerous and should be discouraged because of the high risk of severe injuries and mortality. TBI, open vehicular injuries, and increased ISS were the potential risk factors for mortality. With the vulnerable groups and seasonal patterns identified, this study highlights the need for targeted and integrated intervention approaches to reduce the negative impact of road traffic crashes in our environment. The improvement of health-care facilities, trauma care management, and neurosurgical services will also improve the outcome of these injuries.

Recommendations

There is a need for integrated and targeted interventions to reduce road traffic crashes and injuries. Some of these interventions include public road safety education programs to increase the awareness and adherence to traffic safety regulations by road users, especially during festive seasons and the enforcement of road safety laws such as speed limits, use of crash helmets, and seat belts by law enforcement agencies. The author plans to develop collaboration with relevant government agencies – Police and Federal Road Safety Corps to carry out these interventions which if targeted at the vulnerable road users will reduce the incidence and severity of RTIs.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Research quality and ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board / Ethics Committee. The authors followed applicable EQUATOR Network (http://www.equator-network.org/) guidelines during the conduct of this research project.

Acknowledgments

The author sincerely appreciates the staff of the medical records department of UNTH who assisted with the data collection. Mr Ikechukwu Ani, a statistician was very helpful with data analysis and interpretation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krug EG, Sharma GK, Lozano R. The global burden of injuries. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:523–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curry P, Ramaiah R, Vavilala MS. Current trends and update on injury prevention. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2011;1:57–65. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.79283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peden M, McGee K, Sharma G. The Injury Chart Book: A Graphical Overview of the Global Burden of Injuries. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health organization; 2002. [Last accessed on 2019 Nov 03]. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/92415622X.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 4.García-Altés A, Suelves JM, Barbería E. Cost savings associated with 10 years of road safety policies in Catalonia, Spain. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:28–35. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.110072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toroyan T, Harvey A, Bartolomeos K, Laych Kea. Global Status Report on Road Safety: Time for Action. 2009. [Last accessed on 2019 Nov 03]. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241563840 .

- 6.Peden M, Scurfield R, Sleet D. World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention. 2004. [Last accessed on 2019 Nov 04]. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2004/9241562609 .

- 7.Parkinson F, Kent SJ, Aldous C, Oosthuizen G, Clarke D. The hospital cost of road traffic accidents at a South African regional trauma centre: A micro-costing study. Injury. 2014;45:342–5. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onyemaechi N, Ofoma UR. The public health threat of road traffic accidents in Nigeria: A call to Action. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2016;6:199–204. doi: 10.4103/amhsr.amhsr_452_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Labinjo M, Juillard C, Kobusingye OC, Hyder AA. The burden of road traffic injuries in Nigeria: Results of a population-based survey. Inj Prev. 2009;15:157–62. doi: 10.1136/ip.2008.020255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akinpelu VO, Oladele AO, Amusa YB, Ogundipe OK, Adeolu AA, Komolafe EO. Review of road traffic accident admissions in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. East Cent Afr J Surg. 2006;12:63–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nwadinigwe CU, Onyemaechi NO. Lethal outcome and time to death in injured hospitalized patients. Orient J Med. 2005;17:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madubueze CC, Chukwu CO, Omoke NI, Oyakhilome OP, Ozo C. Road traffic injuries as seen in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Int Orthop. 2011;35:743–6. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1080-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boniface R, Museru L, Kiloloma O, Munthali V. Factors associated with road traffic injuries in Tanzania. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;23:46. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.23.46.7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Racioppi F, Eriksson L, Tingvall C, Villaveces A. Preventing Road Traffic Injury: A Public Health Perspective for Europe. World Health Organization Europe. 2004. [Last accessed on 2019 Nov 16]. Available from: http://www.int/iris/handle/10665/107554 .

- 15.Ohakwe J, Iwueze IS, Chikezie DC. Analysis of road traffic accidents in Nigeria: A case study of Obinze/Nekede/Iheagwa Road in Imo State, Southeastern, Nigeria. Asian J App Sci. 2011;4:166–75. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eke N, Etebu EN, Nwosu SO. Road traffic accident mortalities in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Anil Aggrawals Internet J Forensic Med Toxicol. 2000. [Last retrieved on 2019 Nov 13]. p. 1. Available from: http://www.anilaggrawal.com/ij/vol_001_no_002/paper006.html .

- 17.Chini F, Farchi S, Ciaramella I, Antoniozzi T, Giorgi Rossi P, Camilloni L, et al. Road traffic injuries in one local health unit in the Lazio region: Results of a surveillance system integrating police and health data. Int J Health Geogr. 2009;8:21. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-8-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ul Baset MK, Rahman A, Alonge O, Agrawal P, Wadhwaniya S, Rahman F. Pattern of road traffic injuries in rural Bangladesh: Burden estimates and risk factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:1354. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14111354. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14111354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pathak SM, Jindal AK, Verma AK, Mahen A. An epidemiological study of road traffic accident cases admitted in a tertiary care hospital. Med J Armed Forces India. 2014;70:32–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popoola S, Oluwadiya K, Kortor J, Denen-Akaa P, Onyemaechi N. Compliance with seat belt use in Makurdi, Nigeria: An observational study. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3:427–32. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.117950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin MR, Chang SH, Huang W, Hwang HF, Pai L. Factors associated with severity of motorcycle injuries among young adult riders. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:783–91. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohtasham-Amiri Z, Dastgiri S, Davoudi-Kiakalyeh A, Imani A, Mollarahimi K. An Epidemiological Study of Road Traffic Accidents in Guilan Province, Northern Iran in 2012. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2016;4:230–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newgard CD, Schmicker RH, Hedges JR, Trickett JP, Davis DP, Bulger EM, et al. Emergency medical services intervals and survival in trauma: assessment of the “golden hour” in a North American prospective cohort. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:235–46.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onyemaechi NO, Nwankwo OE, Ezeadawi RA. Epidemiology of injuries seen in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Niger J Clin Pract. 2018;21:752–7. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_263_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faheem AM, Gulzar S, Bilal F. Complications of fracture treatment by traditional bone setters at Hyderabad. J Pak Orthop Assoc. 2009;21:58–64. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Onyemaechi NO, Onwuasoigwe O, Nwankwo OE, Schuh A, Popoola SO. Complications of musculoskeletal injuries treated by traditional bonesetters in a developing country. Indian J Appl Res. 2014;4:313–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Popoola SO, Onyemaechi NO, Kortor JN, Oluwadiya K. Leave Against Medical Advice (LAMA) from in-patient orthopaedic treatment. SA Orth. 2013;12:58–61. [Google Scholar]