Abstract

Introduction:

We aimed to describe the change of suicide rates in China from 2008 to 2017 and provide suggestions for the prevention of suicide.

Subjects and Methods:

A longitudinal study included the time point tracking were used in our study. The suicide data in China were collected from the authoritative official website and yearbook of China from 2008 to 2017. Data were analyzed by SPSS (version 18.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Origin (version 9.0) was used for graph.

Results:

We found that the suicide rate in China showed a downward trend. The suicide rate for males in rural was the highest, followed by rural women. Then urban male, and urban female suicide rate was the lowest. The difference was statistically significant (F = 88.35, P < 0.01).

Conclusions:

The suicide rate in rural areas was higher than that in cities, and men were higher than women. The government should focus on preventing high suicide rates in rural areas, especially men.

Key Words: Area difference, China, suicide, unequal development

INTRODUCTION

It is reported that suicide was the main cause of death in the Chinese population.[1] The suicide rate estimated by the World Health Organization (WHO) is about 16/100,000 people worldwide each year, and suicide is the leading cause of death in persons aged from 15 to 44 years in the world.[2] China accounts for an estimated 22% of global suicides, or roughly 200,000 deaths every year, according to the WHO report.[3] China's age-standardized suicide rate was 9.08/100,000 population (10.53 for males and 7.64 for females) in 2013.[4] Therefore, suicide has been recognized as an important public health issue in the world, especially in China.

In this study, we aimed to test the hypothesis that the difference of suicide rate between males and females in urban and rural areas is related to the difference in economic development between urban and rural areas. We also tried to describe the change of suicide rates in China from 2008 to 2017 and provide theoretical guidance to reduce suicide rate in China.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Data source

The data of suicide rates were obtained from the Chinese Health Statistics Yearbook (CHSYB), National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China (http://www.nhc.gov.cn/). The data are updated every 2 years, so the latest year was 2017. The data come from official historical data, and it has existed objectively since the researcher carried out the research. Our research is a nationwide study. Study size: Data (published by CHSYB from the National Health Commission of P. R. China) are based on roughly 8% of the national population.[5] To ensure the quality of the collected data, any duplicate or redundant information concerning the injuries was cleaned. The study is adhere to the STROBE guidelines.[6]

Participants

The research object is the number of suicides registered with the CHSYB.

The inclusion/exclusion criteria and study design

The inclusion criteria include the following: the suicides rate should be available and complete. The excluding criteria, including data from more than 10 years ago as well as some main data were lost. A longitudinal study included the time point tracking were used in our study.

Definition of study variables

The crude suicide rate obtained directly from the CHSYB is called the suicide rate, and the suicide rate standardized according to gender, age, and urban and rural factors is called the standardized suicide rate. The suicide rate is expressed in units of one hundred thousand people per year (1/100,000).

Statistical methods data analysis

The effective data of relative suicides were extracted by the official website. Epidemiological approach was used to conduct the analysis. Microsoft Office Excel (version 2007) and SPSS (version 18.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) were used for statistical analysis. Origin (version 9.0, Origin Lab, Northampton, Massachusetts, USA) was used for the graph. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to analyze the difference in suicide rates between groups. All tests were two-tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

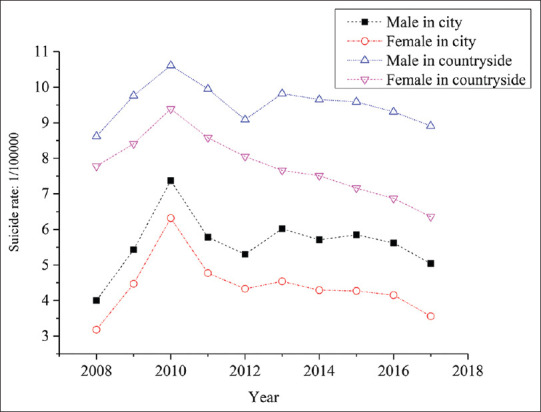

Figure 1 shows that there was a slight rise in the rate of suicide in China from 2008 to 2010. It is obvious in Figure 1. The peak year of suicide rates in the four groups appeared in 2010. Since 2010, female and male suicide rates in city and the rural male suicide rates kept decreased, except 2013. Suicide rates among rural women showed consistently declined. The suicide rate for males in rural was the highest, followed by rural women. Then urban male, and urban female suicide rate was the lowest. In the meantime, among male and female suicide rates between urban and rural areas, rural was higher than urban and males were higher than females. ANOVA showed that the difference was statistically significant (F = 88.35, P < 0.01). The multiple comparisons in ANOVA also showed significant differences between the suicide rates in each group ( P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

The suicide rate of males and females in city and countryside

DISCUSSION

The present study about suicide demonstrated that the suicide rate in China showed a downward trend. This finding was consistent with the previous finding that the suicide rates decreased in both urban and rural regions, as well as males and females.[5] In the 1990s and before 2006, the suicide rate study in China showed that females were higher than males.[7,8,9] Our study also found that the suicide rate was rural greater than that of the urban in same gender, and males were higher than that of females in same region. These results were in agreement with the previous study that since 2006, among rural residents, male suicide rate is higher than female rate.[10] It seems that the current situation of suicide rate between males and females has changed. According to the study of Page et al.,[11] we speculated that the rise trend in the suicide rate in China from 2008 to 2010 may be attributed to the impact of the global economic crisis. Economic crisis can lead to unemployment and let people lose confidence in life and affect the stability of society. Besides economic difficulties, the first wave of baby boomers born in the 1950s and 1960s has started to reach the age of 60 in the 2010s; thus, China is facing an accelerating aging population.[12] Around 2010, its impact on suicide rate has already surfaced in the relatively developed urban areas such as the east and central urban regions of China. Moreover, the massive migration of the central urban young population to the east coast left many older adults behind. It led the central urban areas suffering not only from aging population but also increasing suicide rates among the elderly male since 2008.[13] Those conditions may have driven the spike in suicides in 2010. Rapid macro-socio-economic changes and urbanization may explain the downward trend in the suicide rate in China.[14,15] In 2011, a grassroots medical team with the theme of general practitioners was gradually formed, and the number of psychologists was increased, which is of great significance to improving the mental health of residents and may be related to the decline in suicide rates.[16]

The high suicide rate in the rural area may be attributed to income inequality and differences in delivery of social welfare. Suicide rates so much higher in rural areas than they are in urban areas could be related to rural disadvantages in economy, traffic conditions, and medical resources.[17,18] Similar rural/urban discrepancies in suicide rates have also been found in Australia, India, and Sri Lanka.[17,19] Most of the poor areas' people live on the minimum standard of living granted by the government, whereas for urban people, they have more employment opportunities and more sources of income. Besides, mental health services in rural areas are not as convenient as an urban area. There are various reasons why female suicide rate is lower than male rate. On the one hand, rural women used to be trapped in the countryside, doing farm work, housework, and looking after children. Now, with the improvement of the status of Chinese females, they have better education and employment opportunities. On the other hand, in Chinese culture supported by a grant from, most men need to buy a house and car to get married, provide for their families after marriage, have a lot of financial pressure, and thus have more stress on their lives than women.

To reduce the gap between urban and rural suicide rates, we should vigorously develop the rural economy, promote the social security in the countryside, and strive to reduce the unequal development gap between urban and rural areas. The focus on suicide prevention, which used to be rural women, should now be transformed into rural men. The government should take effective measures to improve the living environment of rural men, provide social support, eliminate the hidden dangers of men at high risk of suicide, and effectively reduce the suicide rate.

Suicide is preventable; to reduce the occurrence of suicide behavior and improve the quality of life of the population, the government should lead and combine various social forces to build a suicide monitoring and intervention system. Conducting mental health education among the public on suicide, suicide-related issues to enhance public awareness of suicide prevention. The improvement of medical conditions and the improvement of road traffic system can shorten the time of medical treatment for attempted suicide and thus reduce the mortality rate. Moreover, there is an important cultural context for successful suicide prevention efforts as well. The necessary cultural norms include (1) positive attitudes toward help-seeking, (2) an accurate understanding of mental health and mental illness, and (3) an emphasis on interdependence and association.[20] In summary, reducing suicide requires government, society, and individuals to work together.

There are some limitations about the study. (1) Data (published by CHSYB from the National Health Commission of P. R. China) are based on roughly 8% of the national population, mainly in areas with relatively good reporting mechanisms, so there is a higher proportion of urban residents in the sample than present in the population as a whole.[5](2) Suicide is a little sensitive topic in China, and the study of suicide in China started later than Western countries. Hence, there is not yet a complete and detailed nationwide injury and death surveillance systems in China. The national monitoring system for suicide attempts is also lacked. Thus, some additional demographic information such as education level, employment status, and medical comorbidities are unavailable. Hence, if we do not know what matters the attempt of suicide most, thus cannot target prevention. As it is well known, the control of drugs and substance abuse in China is very strict. The rate of substance abuse that led to suicide is believed very pretty low, even though there is no national data on the relationship between substance abuse and suicide rate. There is still a lot of research to do in the future in China. We should carry out research on the cause of death registration to explore more consistent and a rational and accurate death registration system.

CONCLUSIONS

Suicide has become a significant population health problem in China. Further efforts to reduce suicide are warranted. The government should put emphasis on high suicide rates in rural areas, especially men.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81560534, PI: Xiuquan Shi).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Research quality and ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board / Ethics Committee. The authors followed applicable EQUATOR Network (http://www.equator-network.org/) guidelines during the conduct of this research project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang L, Liu Y, Liu S, Yin P, Liu J, Zeng X, et al. Status injury burden in 1990 and 2010 for Chinese people. Chin J Prev Med. 2015;49:321–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah A. The relationship between suicide rates and age: An analysis of multinational data from the World Health Organization. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19:1141–52. doi: 10.1017/S1041610207005285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Normile D, Hvistendahl M. Making sense of a senseless act. Science. 2012;338:1025–7. doi: 10.1126/science.338.6110.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao X, Wang LH, Jin Y, Ye PP, Yang L, Er YL, et al. Disease burden caused by suicide in the Chinese population, in 1990 and 2013. Chin J Prev Med. 2017;38:1325–9. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, Sun L, Liu Y, Zhang J. The change in suicide rates between 2002 and 2011 in China. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44:560–8. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips MR, Liu H, Zhang Y. Suicide and social change in China. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1999;23:25–50. doi: 10.1023/a:1005462530658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ji J, Kleinman A, Becker AE. Suicide in contemporary China: A review of China's distinctive suicide demographics in their sociocultural context. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2001;9:1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yip PS, Liu KY, Hu J, Song XM. Suicide rates in China during a decade of rapid social changes. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:792–8. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0952-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu ZY, Huang YQ, Ma C, Shang LL, Zhang TT, Cheng HG. Suicide rate trends in China from 2002 to 2015. Chin Ment Health J. 2017;31:756–67. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page A, Morrell S, Hobbs C, Carter G, Dudley M, Duflou J, et al. Suicide in young adults: Psychiatric and socio-economic factors from a case-control study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:68. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhong BL, Chiu HF, Conwell Y. Rates and characteristics of elderly suicide in China, 2013-14. J Affect Disord. 2016;206:273–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sha F, Chang Q, Law YW, Hong Q, Yip PS. Suicide rates in China, 2004-2014: Comparing data from two sample-based mortality surveillance systems. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:239. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5161-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blasco-Fontecilla H, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Garcia-Nieto R, Fernandez-Navarro P, Galfalvy H, de Leon J, et al. Worldwide impact of economic cycles on suicide trends over 3 decades: Differences according to level of development. A mixed effect model study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:pii: e000785. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun J, Guo X, Zhang J, Jia C, Xu A. Suicide rates in Shandong, China, 1991-2010: Rapid decrease in rural rates and steady increase in male-female ratio. J Affect Disord. 2013;146:361–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu XS. Deepening medical and health reform promoting the construction of healthy China calling for the development of general medicine. Chin J Pract Rural Doctors. 2016;1:9–11. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen YY, Wu KC, Yousuf S, Yip PS. Suicide in Asia: Opportunities and challenges. Epidemiol Rev. 2012;34:129–44. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxr025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang CW, Chan CL, Yip PS. Suicide rates in China from 2002 to 2011: An update. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49:929–41. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0789-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Värnik P. Suicide in the world. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:760–71. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9030760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christoffel T, Gallagher SS. Injury Prevention and Public Health: Practical Knowledge, Skills and Strategies. 2nd ed. USA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]