Abstract

Malaysia recorded its first case of COVID-19 on January 24th, 2020 with a stable number of reported cases until March 2020, where there was an exponential spike due to a massive religious gathering in Kuala Lumpur. This caused Malaysia to be the hardest hit COVID-19 country in South East Asia at the time. In order to curb the transmission and better managed the clusters, Malaysia imposed the Movement Control Order (MCO) which is now in its fourth phase. The MCO together with targeted screening have slowed the spread of COVID-19 epidemic. The government has also provided three economic stimulus packages in order to cushion the impact of the shrinking economy. Nonetheless, early studies have shown that the MCO would greatly affect the lower and medium income groups, together with small and medium businesses.

Keywords: COVID-19, Malaysia, Movement Control Order, Economic impact

Introduction

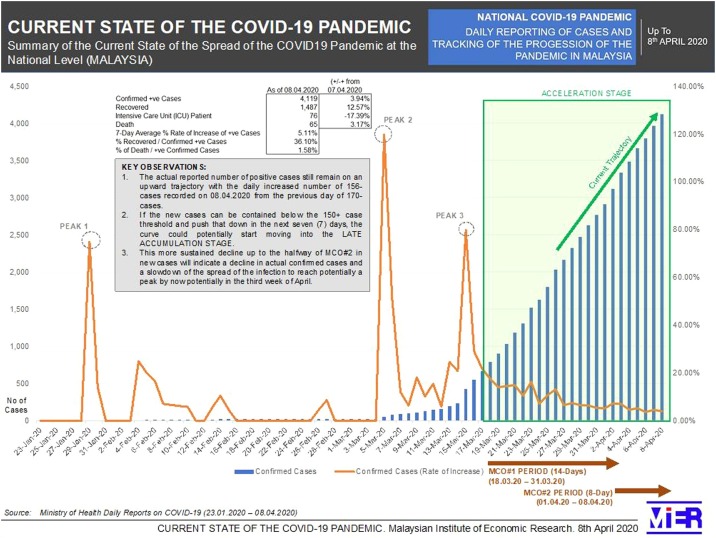

The COVID-19 virus first emerged in Wuhan, China in late December 2019, and presented initially as pneumonia of an unknown cause amongst traders and visitors to Wuhan's seafood market which was also selling exotic wild animals [1]. From a zoonotic transmission, the virus has evolved into a person-to-person transmission, with a widening clinical spectrum from asymptomatic infection to respiratory tract spectrums and even death [2]. This alerted the international community and since then the disease has spread worldwide, involving more than 180 countries forcing the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 12th, 2020 [3]. Malaysia recorded its first case on January 24th, 2020 and up until March 2020, case numbers remained relatively low and occurred mainly amongst foreign arrivals from China [4]. Nonetheless, Malaysia had its first large daily spike on March 15th, 2020 with 190 cases, most of them being linked to a massive religious event in Kuala Lumpur. The following day (March 16th, 2020) the cumulative cases had surpassed the 500th mark with the first COVID-19 death reported on 17th March, 2020 (Fig. 1 ) [4]. Due to the rapid increase in positive cases and the difficulty in tracing the contacts, the government of Malaysia has imposed the Movement Control Order (MCO) on the 18th March 2020 [5].

Fig. 1.

State of the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia demonstrating initial clusters and trajectory projection overtime.

MIER Report, April 8, 2020.

The implementation of the MCO – the early challenges

Following the implementation of the MCO, all Malaysians were instructed primarily to stay indoors. Other restrictions imposed included prohibition of mass gatherings, health screening and quarantine for Malaysians coming from abroad, restriction on foreigners entering the country and closure of all facilities except primary and essential services such as health services, water, electricity, telecommunication and food supply companies [6].

The early management of COVID-19 in Malaysia, prior to the MCO, was challenging. Initially, the reporting of COVID-19 was classified as an influenza infection due to the concurrent winter season in the northern hemisphere countries together with the movement of people during the end of year holiday season. Based on this presumption, although initial precautions had been implemented by the Ministry of Health, earlier actions identified people who were at risk and those with influenza like illness to be screened and further managed. Due to the novel characteristics of the virus, many countries including Malaysia had assumed that the COVID-19 infection could be a local outbreak whereby chances of the spread to other countries were slim [7]. Many countries had initially downplayed the severity of the virus as there was a lack of understanding of the characteristics of transmission [6]. In addition, during the first phase of the outbreak, Malaysia encountered a unique situation where a sudden change of government left the country with a void in good governance. The management of the outbreak was entrusted to the Ministry of Health (MOH) alone; without cohesive management by other government agencies. During this interim phase, the COVID-19 outbreak was managed by the civil servants of the MOH, which is known for its tightly knit professional core that is independent of politics, headed by the highly capable Director General of Health who was voted one of the top three medical doctors in the world in handling the COVID-19 crisis [8], [9]. Although the medical fraternity in Malaysia is diverse in their provision of service, they share a common thread that is set by professional and medical ethics, and follow adherence to evidence-based medicine in delivery of medical care and public health services.

At the early stage of the outbreak, East Asian countries had already experienced a surge of positive cases which had prompted the respective governments to impose stricter public health measures. This included movement restrictions, social distancing and banning of mass gatherings [10]. On the other hand, until the declaration of the pandemic by the WHO on the 12th March, 2020, many countries including Malaysia were managing the infection in a less aggressive manner. These countries had kept their borders open to visitors with a lack of screening at entry points and had left those with infected status to enter freely into the country. This in turn created a sense of insecurity amongst the public.

As a result, Malaysia faced two different COVID-19 clusters within a short period of time, the first being from imported cases and the latter from the religious mass gathering involving several thousand participants from more than 15 different countries. Due to the exponential spike in the COVID-19 positive cases, the state of MCO was declared on March 16th, 2020 to commence on March 18th, 2020 [10].

Flattening the curve – the Malaysian initiative

Whilst Malaysia's decision to implement the MCO was slightly later compared to other affected countries such as South Korea, the result of this implementation had surprised many. Earlier in March, JP Morgan Chase & Co together with Malaysia Institute of Economic Research (MIER) [11] predicted that Malaysia will have an acceleration of cases that would peak mid-April, with between 6000 and 8500 cumulative infections.

With the concurrent onset of the COVID-19 clusters, the government needed drastic interventions to prevent the prediction from becoming a reality. The approach taken by Malaysia had been based on past experiences from China and South Korea. China's drastic measure of controlling the spread of the virus in Wuhan had showed resounding success after more than 70 days of a strictly controlled, tight lockdown. Nonetheless, this may not have been a suitable option for Malaysia [12]. The nature of Malaysians who are more sociable and have the affinity for social gatherings might pose as a difficult challenge should the complete lockdown be imposed. On the other hand, South Korea had used a different approach. The South Korean model relied heavily on two approaches: mass screening to detect and treat positive cases and strong nationwide IT coverage to trace and inform the public of the COVID-19 progress [13], [14]. Although the South Korean model appeared to be more suitable, the issues of constrained resources and limited IT coverage in rural areas made it a challenge should it be implemented in Malaysia.

Hence, the MOH and the government designed a combination of MCO measures and targeted screening approaches to be used during the mitigation phase. This was to create a small window of opportunity aiming to break the transmission chain of the virus. Firstly, the government's implementation of the MCO in restricting mass movement was aiming to achieve two objectives: slowing the transmission chain in the community and allowing the MOH to trace, isolate and manage the identified positive cases. Secondly, with the restricted movement measures in place, the MOH would be able to fully screen and manage the existing clusters as to prevent the transmission from extending beyond the first or second generation of infection. In order to accomplish this within the incubation period time frame (0–14 days post exposure), collaborative approaches between the sectors were used. These included the health sector, police, military, academicians, statisticians and others to work together in curbing the transmission. Each of these sectors worked differently but ultimately towards the same goal. For example, whilst the health sector was responsible for managing the medical and public health aspects of the infection, the police and military worked closely together to enforce the movement restriction orders, especially in the red zone areas. As COVID-19 situation changes frequently, standardized operating procedures (SOP) were needed for the references of the health care workers and the public. Hence, the academics and statisticians often worked hand in hand with the government, in advising and providing data in managing the pandemic in Malaysia.

Thirdly, an aggressive screening approach has been used to isolate and treat positive cases. These include identifying at risk individuals within the identified clusters, screening the contact and close contact individuals to the positive cases, and also door-to-door screening exercises in red zone areas. Although Malaysia has yet to reach the target of 16,500 tests daily (currently 11,500 tests are conducted daily, 69.7% coverage), the current testing is able to detect and identify a significant percentage of positive cases per population (7.2% of the positive rate vs. the WHO standard of 10.0% of the positive rate) which is at par with the current WHO standards [15]. The expansion of the number of laboratories from 4 to 48 laboratories nationwide has enabled the testing to be done more quickly and within the targeted time frame. Fourthly, using mass media and IT technology, the government has been able to reach a wider public coverage and within a shorter period of time. The dissemination of information includes the following: regular media announcements from the MOH regarding social distancing, hand washing and inviting contacts from the religious cluster to come forward for testing, daily personal texting to individual's smartphones of government's directives and advice, and also daily countering of COVID-19's fake news as to prevent confusion and panic amongst the public. In addition, daily media press conferences by the same authorities (Director of Health and The Minister of Defence) have created a sense of security and confidence amongst the public during the period of this pandemic.

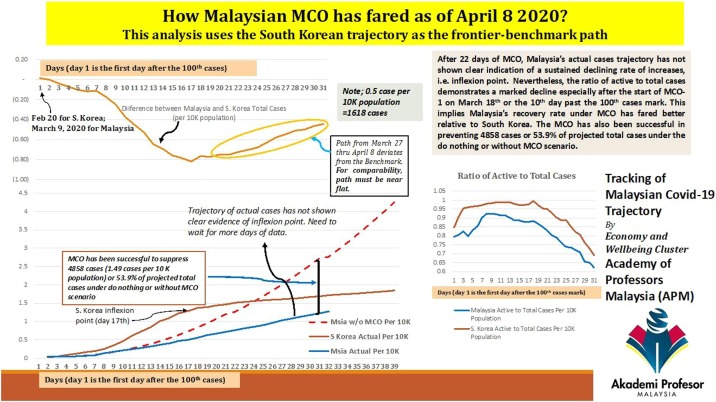

This, together with aggressive intervention in the managing of COVID-19 cases in hospitals using methods of strict surveillance for the positive cases, early intervention in symptomatic cases and a combination drug therapies have shown a dramatic improvement in the recovery rate, starting from Day-7 after the start of MCO-1 or the 17th day after the hundredth case (Fig. 2 ). Up until the 9th of April, 2020, Malaysia had reported a recovery rate of 38% with a fatality rate of 1.58% [15]. In terms of early intervention in symptomatic cases, Malaysia has adopted the clinical staging in identifying those who are at risk of respiratory deterioration by instituting a combination of drug therapies. There are five clinical stages: asymptomatic (stage 1), symptomatic but without pneumonia (stage 2), symptomatic with pneumonia (stage 3), symptomatic, pneumonia and requiring supplemental oxygen (stage 4) and critically ill with multi-organ failure (stage 5). Several warning signs include fever, tachycardia, dropping of ALC and an increase in CRP levels which may denote deterioration in general well-being, even though patients are still in stage 1 and stage 2 [16]. In terms of combination drug therapies, until now there is still no specific treatment for the COVID-19 infection that is currently approved with limited data on experimental agents including chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir-ritonavir, interferon, ribavirin etc, as the situation is dynamic and changing daily [16]. Up to recently, patients were given a combination of drugs based on clinical staging and the patient's clinical condition.

Fig. 2.

State of COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia demonstrating comparison of recovery rate between Malaysia and South Korea.

Academy of Professors Malaysia Report, April 8, 2020.

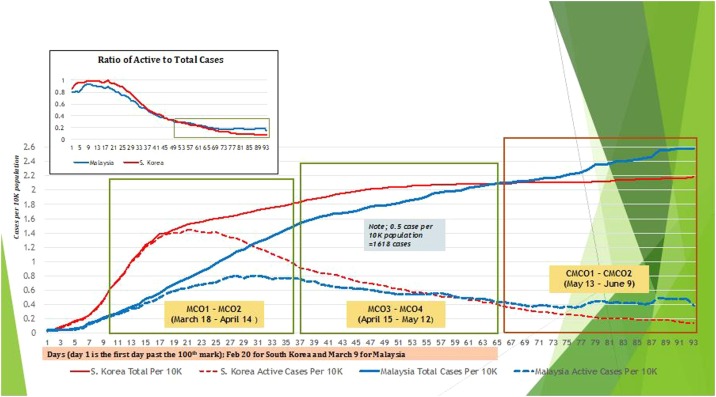

Looking into Fig. 3 [17], the rise of daily cases from the 3rd of March, 2020 (peak 2) to the 15th of March, 2020 (peak 3) followed closely the predictive trajectory with cases remaining in an upward trend. The actual cumulative confirmed cases as compared to projected cumulative confirmed cases remained the same until 23rd March 2020, with projected cases predicted to have an exponential peak from 30th March onwards. The first phase of MCO (MCO-1) of a 14 days’ duration (from the 18th of March to the 31st of March, 2020) started to show a small gap between actual and projected cumulative cases. Nevertheless, the day to day cases remained unstable. The results of the second phase of the 14-day MCO (commenced April 1st) showed interesting findings. Up to 8th April 2020, the actual reported cases were lower compared with the projected baseline trajectory (5.11% vs. 7.44%). Although there was a promising sign that the daily cases were beginning to indicate a downwards trend, the overall trend remained unstable, with cases fluctuating day to day, and small peaks in between. Even 24 days after the implementation of the MCO (April 11, 2020), the desired effect of flattening the cumulative case curve remained elusive. Although the MCO-1 and MCO-2 have by far successfully suppressed approximately 6352 cases (58% of the total projected cases without the MCO scenario as of April 11), it had yet to reach the inflexion point, which typically denotes the start of a sustained diminishing rate of increases in cases. This compares to South Korea where the inflexion point for total cases was achieved 17 days after the hundredth case. As a result, on the 10th of April, the government announced a third MCO extension (MCO-3) for another 14 days (from the 15th of April to the 28th of April, 2020) followed by a fourth MCO (MCO-4) extension (29th of April 2020 to 15th of May 2020) with the aim to further widen the window of opportunity to flatten the curve and deny the baseline projection. From Fig. 3, the COVID-19 cases in Malaysia showed two interesting findings. Firstly, the overall cumulative actual cases trajectory (presented in blue line) appeared to push the active cases curve upwards, but it was markedly lower than the projected baseline trajectory. The effect of the MCO in flattening the curve can be seen from the mid MCO-3, with relatively lower trend in MCO-4 and further. This prompted the government to start the Conditional Movement Control Order (CMCO-3 and CMCO-4) from 13th of May 2020 to 9th of June 2020. The CMCO has eased some of the strict restrictions imposed to the public and reopening the national economy in a controlled manner. However, when benchmarked to South Korea, the normalized cases show considerable weakening of relative performance, possibly due to the increased number of testing in recent weeks and spikes attributed to foreign workers.

Fig. 3.

Malaysia's performance in managing COVID-19 in terms of comparison with South Korea as benchmarking (reported as cases per 10,000 population).

MIER Report, June 9, 2020.

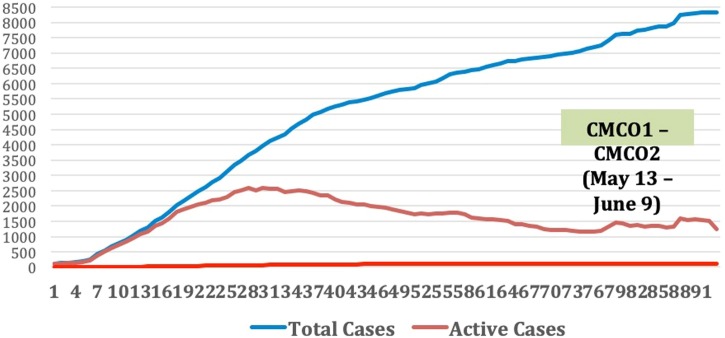

Secondly, with regards to the actual active cases (presented in blue dotted line), the data suggests that active cases may have reached their peak on April the 6th, the 28th day after the 100th case or the 18th day after the start of the first MCO. From April the 11th, the MCOs seem to show an effect to reduce the active cases. However, it lags from South Korean's benchmark model by seven days. Malaysia's four MCO series followed by two CMCOs have worked very well, as reflected especially by the relatively stable and low number of active cases during the CMCO period. Fig. 4 illustrates the actual number of COVID-19 cases in Malaysia in terms of cumulative and active cases. There is an apparent gap between the cumulative cases, which stood at 8000 cases at the end of CMCO period and the number of active cases with the risk of infectivity ranging from 1200 to 1500 cases towards the end of the CMCO period. This widening gap proved that the moves in restricting the public movement together with targeted mass screening approach and early intervention were able to curb the surge of COVID-19 infection in Malaysia.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of cumulative and active cases of COVID-19 infection in Malaysia during the period of MCO and CMCO.

Academy of Professors Malaysia Report, June 9, 2020.

The impact of MCO to nation's health and economy

The tailor-made combination of movement restriction orders and the aggressive screening exercises have given the much needed hope to Malaysia in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. Whilst the flattening curve effect and the turn-around inflexion point remain elusive with a possibility of emerging of a new cluster amongst the population, there is an early sign that this combined approach is appropriate for Malaysia. Admittedly, prolonging the MCO is not without its adverse implications.

The impact on public health

Most of the legal procedures on infection disease prevention and control is documented in Act 342 Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases Act 1988 under the Laws of Malaysia [16]. The MOH Malaysia has also issued COVID-19 guidelines in its portal [17] which follow recommendations of the WHO interim guidance on infection prevention and control during health care when the COVID-19 is suspected.

The first requirement in any epidemic would be crisis procurement of healthcare equipment such as test kits, personal protective equipment (PPE) and ventilators. According to the WHO Scientific Brief (2020) of the current evidence, the COVID-19 virus is primarily transmitted between people through respiratory droplets and contact routes. Airborne transmission may be possible in specific circumstances and settings in which procedures or support treatments that generate aerosols are performed: endotracheal intubation, bronchoscopy, open suctioning, administration of nebulized treatment, manual ventilation before intubation, turning the patient to the prone position, disconnecting the patient from the ventilator, non-invasive positive-pressure ventilation, tracheostomy, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

The guidelines [17] have recommended airborne precautions (using PPE) when handling suspected infected persons during procedures and support treatments that generate aerosol. The difficulty is that demand for the equipment exceeds its supply. The test kits and ventilators would have to be procured from overseas. Initially there was concern that the current stock of PPE would be insufficient to meet the expected demand but Malaysians have risen to the occasion in a unique show of support and solidarity by either directly producing the PPE or donating towards the manufacture or procurement of PPE. From within healthcare facilities to private conglomerates through non-governmental organizations, prison and orphanages, many have contributed to this endeavour, regardless of race, religion or social standing [18], [19], [20], [21].

The second requirement is to test as many as possible since the testing of all is not financially feasible or logistically possible. In this aspect, the MOH has purchased high accuracy rapid test kits from South Korea and is able to conduct about 22,000 tests per day. The current RT-PCR test whilst highly accurate with specificity and sensitivity rates of 90 percent and above, takes 2–3 days to obtain the results and is relatively expensive (MYR 380–700/test, USD 89–163/test). Until May the 25th, 2020 a total of 513,370 tests have been conducted of which 7417 (1.45%) were positive [22] Malaysia is doing a targeted screening approach, by which areas with COVID-19 infections are categorized as red zone (high infectivity), orange (moderate infectivity) and green (low infectivity). Of the red zones areas, further enhanced MCO is implemented as to do door-to-door screening and testing.

Thirdly, to prevent infection from outside Malaysia, all overseas inbound passengers are quarantined for 14 days. The Defence Minister Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob made an announcement on April the 2nd, that the compulsory 14-day quarantine order for all Malaysians and visitors returning from overseas would start on April the 3rd, 2020. All returning Malaysians or foreign visitors who enter the country are subjected to the quarantine procedure at all entry points, irrespective if they travelled by air, sea or land [23]. Malaysia has identified 409 quarantine centres across the country, that once opened could accommodate over 40,000 people at the same time. As at April the 4th 2020, a total of 1188 Malaysians who returned from abroad had been quarantined [24]. All symptomatic COVID-19 positive persons have been isolated in hospitals and quarantine centres. Unfortunately, Malaysia has not been able to identify asymptomatic positive cases, except a few who were in contact with the positive cases, due to lack of rapid testing. This creates a lag between identified cases and potential contacts, resulting in further spread of infection in the community [25], [26].

The impact to economy

The Malaysian government, over a span of six weeks, has announced three economic stimulus packages with a total value of MYR260 billion (USD 60 billion), representing some 17% of the country's GDP. It mainly comprises loan deferments, loan guarantees, one-off cash assistance, credit facilities and rebates as well as a direct fiscal injection of MYR35billion (USD 8 billion) [27], [28]. The bulk of this package targeted the lower and middle income groups, followed by assistance to small and medium enterprises which contribute 66% to employment and 38% to the country's GDP. The aim is to alleviate difficulties faced by people in the lower income group who are bound to face severe disruptions to livelihoods during the MCO period.

The Malaysian Institute of Economic Research's forecast shows that in the absence of strong economic stimulus, Malaysia's real GDP may shrink by about 2.9% in 2020 compared with 2019, resulting in an estimated 2.4 million people losing their jobs. Of these, 67% will be non-salaried, unskilled workers [26]. Kochar and Barroso's (2020) report for the U.S. also found that most workers that are at higher risk of job loss due to COVID-19 are the low-wage workers. Amongst the 19.3 million American workers aged 16–24, 9.2 million (or almost 50%) are employed in the services-sector, which face a greater likelihood of closure. Therefore, the young people working in this sector are disproportionately affected by layoffs related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The situation may not be much different in Malaysia. Recently, the Academy of Professors Malaysia (APM) conducted a study on some 900 online respondents and found that 91% were able to sustain themselves for the first two weeks of MCO (ending 31 March). However, only 58% would be able to sustain themselves if the MCO was extended by another two weeks (to 14th April). About 43% were fearful of losing their jobs, mainly amongst the young age groups of 18–37. Whilst the economic stimulus may be able to provide some relief to households and businesses, many are concerned about the bleak reality and uncertainties of COVID-19 and its impact should the MCO be extended further. Many economists are now calling for the government to identify optimal control measures that weigh the health benefits of control against its overall economic costs.

The way forward and conclusion

At the time of writing (26 May), Malaysians are in phase 4 of the MCO which is scheduled to end on 9th of June, 2020. This phase, known as the Conditional Movement Control Order (CMCO), allows certain businesses to open and a more relaxed movement of people with mandatory standard operating procedures, such as temperature checks, wearing of face masks, social distancing of 2 m, use of hand sanitizers regularly, no mass gatherings, registering names and hand-phone numbers at each premise visited.

There is a change in the profile of people detected positive in Malaysia since early May. By the 10th of May, 2020, it was evident that new clusters had emerged amongst foreign nationals, making up between 70% and 80% of new COVID-19 cases [29]. By the 21st of May, 2020, new clusters of infection were detected amongst illegal foreign workers at immigration detention centres initially in Bukit Jalil (35 non-Malaysian cases), followed by 21 cases amongst foreign detainees in Sepang on the 23rd of May and followed by a further 27 cases in Semenyih on the 24th of May [30]. During the Eid celebration speech on the 23rd of May, the Prime Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin informed the public that any decision to end the CMCO would depend on how far the people can conform to the Government's standard operating procedures and apply them as part of daily life in order to stop the spread of COVID-19. He implied that an exit plan for the MCO was in the works whilst urging community leaders to take charge in helping to break the transmission of COVID-19 [31].

Prior to the Prime Minister's announcement, an article was published in Kolumnis Awani (local news channel) on the 13th of May with reference to community empowerment which contained the following suggestions for community leaders:

-

1.

To follow SOP's laid out by the Ministry of Health, National Security Council and Prime Ministers Department.

-

2.

To take charge of individual and community health prevention activities.

-

3.

To stop the community misinterpretation of messages or instructions that are announced by the government.

-

4.

To establish a community system that works with the government (local or federal) in managing COVID-19 in the community including using existing community committees in keeping the community safe, working with age-specific groups in reaching out to ‘at risk’ individuals or ‘in-need’ families and activating neighbourhood watch to keep track of the communities’ well-being.

-

5.

To monitor the mental stability of households and the community and assist in getting help for those suffering from mental issues for example depression and anxiety.

-

6.

To be aware of any community members needing basic needs for example food packs, medical aid and be able to deal with the needs.

On June 7, 2020, Prime Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin announced that the Conditional Movement Control Order (CMCO) would end June 9, 2020 and be replaced with the Recovery Movement Control Order (RMCO). The government eased restrictions under the condition that the public take responsibility in adhering to the SOPs that have been set. Community leaders, NGO leaders and employers must empower the people to work together to break the chain of the COVID-19 virus transmission and comply with SOPs [32].

The tailor-made in phases MCO and the aggressive screening method appear to show clear signs of slowing down the infection amongst the local population but the number of positive cases are rising again due to transmission amongst foreign workers and imported cases from Malaysians returning from abroad. The challenge now is to contain the infection amongst the illegal foreign workers in the country who will have to be identified, tested, treated and repatriated. The local spread has to be contained by educating the public to be more socially responsible and self-disciplined. The uncertainty of COVID-19 is now reaching beyond health impact, outreaching to economic and livelihood implications of this country and it can only be overcome by good communication, clear and transparent information flow as well as cooperation between the people of Malaysia and the authorities.

Authors’ contributions

NA Aziz and Suleiman A prepared and wrote the initial draft. Othman J with MIER calculated and prepared the epidemiological analyses. Lugova H. conducted proof reading, editing and alignment of the article. All four authors wrote and checked the final manuscript

Funding

No funding sources.

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Acknowledgements

This review is the cumulative works of the Economy and Well-Being Cluster, Academy of Professors Malaysia (APM), an independent body of senior academics that advises and works with the Government of Malaysia on various issues, including the handling and management of the COVID-19 outbreak. We thanked the Director General of Health, Datuk Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah and his team for the data and record of the COVID-19 outbreak in Malaysia. The analyses of the data are being done by the Malaysia Institute of Economic Research (MIER) and the aforementioned cluster of APM. Finally, we acknowledge and thank all health care workers, front-liners and the public of Malaysia who are now working, donating and supporting the country towards the COVID-19 cause.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2020.08.007.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO Europe . March 12, 2020. WHO announces COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic. Date accessed April 11, 2020. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health, Malaysia . January 24, 2020. Press statement KPK 24th January 2020. Date accessed: April 9, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health, Malaysia . May 25, 2020. Press statement KPK 25th May 2020. Date accessed: May 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.March 16, 2020. COVID-19: Movement Control Order imposed with only essential sectors operating. Nation. New Straits Times. Date accessed: May 25, 2020. https://nst.com.my/news/nation/2020/03/575177/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.April 4, 2020. Covid-19: 109 new cases, death toll now at 67. Nation, The Star Online. Date accessed: April 11, 2020. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2020/04/09/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.February 26, 2020. How will Malaysia confront coronavirus without a health minister? Week in Asia. The South China Morning Post. Accessed: May 25, 2020. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/opinion/article/3052446/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.April 14, 2020. In the spotlight – the doctors at the top: truthtellers and heartthrobs. World. CGTN. Accessed: May 25, 2020. https://news.cgtn.com/news/2020-04-14/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Editorial COVID-19: learning from experience. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30686-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou F., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatient with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.March 31, 2020. Restrictions on movement in some Southeast Asian countries to fight COVID-19 have been patchy, even scary. Commentary, Channel News Asia Online. Date accessed April 10, 2020. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/commentary/coronavirus-lockdown/2020/03/31/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.March 16 2020. PM: Malaysia under movement control order from Wed until March 31, all shops closed except for essential services. Home, Malay Mail Online. Date accessed: April 11, 2020. https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2020/03/16/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan J.P. 2020. COVID-19 likely to peak next month in Malaysia. https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2020/03/25/. Business, The Star Online, March 25, 2020. Accessed April 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdullah J.M., Wan Ismail W.F.N., Mohamad I., Ab Razak A., Harun A., Musa K.I., et al. A critical appraisal of COVID-19 in Malaysia and beyond. Malays J Med Sci. 2020;27(2):1–9. doi: 10.21315/mjms2020.27.2.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ministry of Health Malaysia, COVID-19 (Guidelines), Annex 2e Clinical Management of Confirmed Case. https://www.moh.gov.my/moh/resources/Penerbitan/Garispanduan/COVID19/Annex-2e_Clinical_management_22032020.pdf.

- 17.South Korea took rapid, intrusive measures against Covid-19 – and they worked https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/20/. The Guardian International Edition, March 20 2020, Date accessed: April 11, 2020.

- 18.WHO Scientific Brief . March 29, 2020. Modes of transmission of virus causing COVID-19: implications for IPC precaution recommendations. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/modes-of-transmission-of-virus-causing-covid-19-implications-for-ipc-precaution-recommendations) [Google Scholar]

- 19.2020. Coronavirus: South Korea's success in controlling disease is due to its acceptance of surveillance, The Conversation Australia Edition, March 20, 2020. Date accessed: April 11, 2020. https://theconversation.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.2020. Number of COVID-19 tests might seem low for these two reasons, says Health D-G. News, The Malay Mail Online, 2 April 2020. Accessed: April 10, 2020. https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2020/04/02/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministry of Health, Malaysia . 2020. Press statement KPK April 9, 2020. Date released April 9, 2020. Date accessed: April 9, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malay Mail . May 5, 2020. MOH: Malaysia to get 100,000 Covid-19 antigen rapid test kits by end of the week. https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2020/05/05/moh-malaysia-to-get-100000-covid-19-antigen-rapid-test-kits-by-end-of-the-w/1863317. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malaysia Institute of Economic Research; 2020. National COVID-19 pandemic: daily reporting of cases and tracking of the progression of the pandemic in Malaysia, up to 7th April 2020. Date released: April 8, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ministry of Health Malaysia; March 25, 2020. Guidelines on COVID-19 Management in Malaysia No. 5/2020 official portal. Date accessed April 12, 2020. http://www.moh.gov.my/index.php/pages/view/2019-ncov-wuhan-guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 25.March 19, 2020. Infection prevention and control during health care when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected. WHO interim guidance. Date accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance. [Google Scholar]

- 26.March 30, 2020. UMK makes PPE and shield visors for Covid-19 front-liners New Straits Times Online. Date accessed: April 12, 2020. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2020/03/579548/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melanaie Chalil, Malay Mail; April 2, 2020. Malaysian prison inmates sew protective gear for frontliners amid shortage in fight against Covid-19. Date accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.malaymail.com/news/life/2020/04/02. [Google Scholar]

- 28.April 2, 2020. COVID-19: orphans, very poor RPWP generates thousands of PPEs for national front. Aza Jemina Ahmad, Astro Awani. Date accessed April 12, 2020. http://www.astroawani.com/berita-malaysia/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Edge Markets, Malaysia reports 67 new Covid-19 infections today, again mostly among foreigners. https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/malaysia-reports-67-new-covid19-infections-today-again-mostly-among-foreigners.

- 30.CNA . May 21, 2020. COVID-19: new cluster involving immigration detainees identified in Malaysia. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/covid-19-new-cluster-malaysia-detainees-12756824. [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Star TV . May 23, 2020. Muhyiddin's Raya message: greater responsibility to end conditional MCO. https://www.thestartv.com/v/muhyiddin-s-raya-message-greater-responsibility-to-end-conditional-mco. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Povera A., Chan D. June 7, 2020. RMCO based on 7 strategies. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2020/06/598728/rmco-based-7-strategies. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.