Abstract

PURPOSE

As a result of their immunocompromised status associated with disease and treatment, patients with cancer face a profound threat for higher rates of complications and mortality if they contract the coronavirus disease 2019 infection. Medical oncology communities have developed treatment modifications to balance the risk of contracting the virus with the benefit of improving cancer-related outcomes.

METHODS

We systemically examined our community cancer center database to display patterns of change and to unveil factors that have been considered with each decision. We studied a cohort of 282 patients receiving treatment and found that 159 patients (56.4%) had treatment modifications.

RESULTS

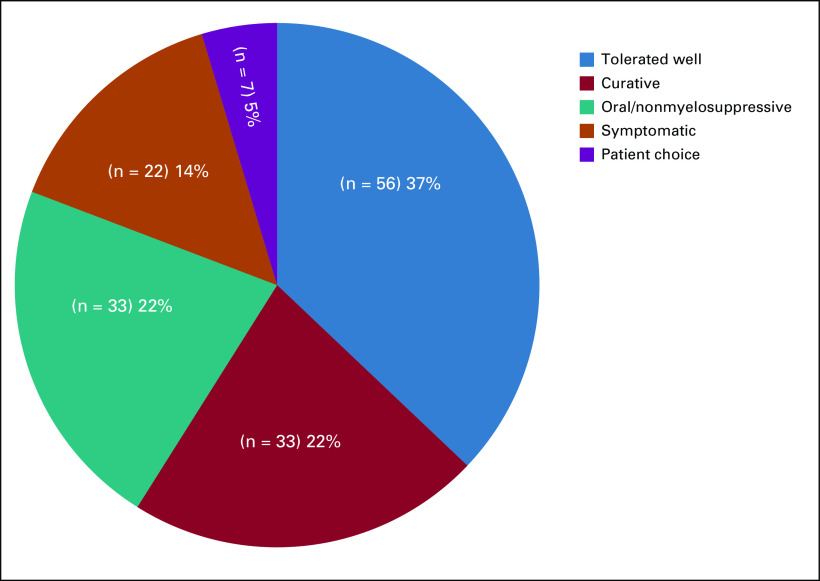

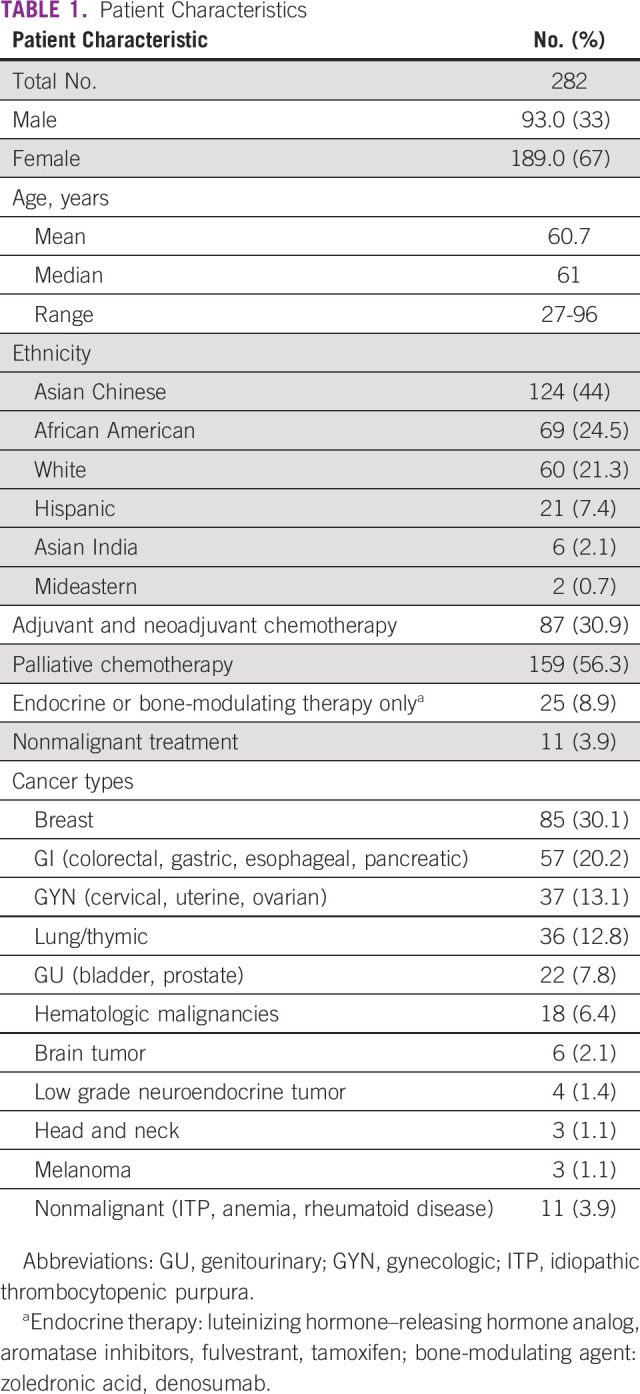

The incidence of treatment modification was observed in patients undergoing adjuvant and neoadjuvant (41.4%), palliative (62.9%), or injectable endocrine or bone-modulating only (76.0%) treatments. Modifications were applied to regimens with myelosuppressive (56.5%), immunosuppressive (69.2%), and immunomodulating (61.5%) potentials. These modifications also affected intravenous (54.9%) and subcutaneous injectable treatments (62.5%) more than oral treatments (15.8%). Treatment modifications in 112 patients (70.4%) were recommended by providers, and 47 (29.6%) were initiated by patients. The most common strategy of modification was to skip or postpone a scheduled treatment (49%). Among treatment with no modifications, treatment regimens were maintained in patients who tolerated treatment well (37.0%), in treatments with curative intent (22%), and in symptomatic patients who required treatment (14%).

CONCLUSION

Our observation and analysis suggested that the primary goal of treatment modification was to decrease potential exposure. The pattern also reflected the negative impact of the pandemic on health care providers who initiated these changes. Providers have to consider individualized recommendations incorporating multiple factors, such as tolerance, potential toxicity, treatment nature and route, and disease severity.

INTRODUCTION

The unprecedented coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has presented a public health challenge globally. Since the first confirmed case reported in New York City on March 1, 2020, there have been more than 371,711 confirmed cases and 23,959 deaths by May 31, 2020.1 Initial retrospective studies from China reported higher complication and mortality rates in patients with cancer compared with the general population owing to their immunocompromised status induced by the disease and/or treatment.2-6 In an early Italian case-fatality study, approximately 20% of patients who died of COVID-19 had active cancer.7

CONTEXT

Key Objective

In the face of the coronavirus pandemic at a community cancer center in New York City, we wanted to know how often chemotherapy schedules were modified and what the key factors were that influenced the decision-making process.

Knowledge Generated

Treatment modifications were made in 56% of patients in all treatment categories, including both myelosuppressive and nonmyelosuppressive regimens. These modifications affected intravenous and subcutaneous injectable treatments more than oral treatments. Health care providers recommended changes in 70.4% of cases, frequently using a strategy of skipping or postponing a scheduled treatment (49%). Among patients who maintained treatment intensity, 37% of them tolerated treatment well, 22% had treatments with curative intent, and 14% of them were symptomatic and required treatment.

Relevance

The decision to modify chemotherapy regimens should take into consideration both the benefit and risk of treatment versus the potential of increased exposure to COVID-19 infection. Reducing treatment frequency can reduce exposure and, in turn, morbidity and mortality.

Since the start of the outbreak, the oncology community has faced a tremendous responsibility to make a correct recommendation for each individual patient receiving treatment. Oncologists had to consider the benefits of continuing or initiating cancer treatment, with many of these being myelosuppressive or immunosuppressive in nature, or both, against the risk of patients contracting the virus and developing severe complications. In addition, a PAUSE order was issued in New York State on March 22, 2020, and social distancing required the cancer center to reduce its occupancy even for patients receiving chemotherapy. Medical societies have published some timely guidelines that mainly discussed the sequence of multimodality treatments, whereas chemotherapy treatment decisions for individual patients were left to individual providers.8-10 The COVID-19 cases started to increase exponentially in New York City in early March, and we witnessed the fear and its impact on both patients with cancer and providers, who started to make recommendations on chemotherapy regimen modifications.

In this study, we aimed to examine the prevalence and characteristics of the treatment modifications carried out in our community cancer center. We were interested in uncovering the factors that lead to the decision, and we analyzed the influence of such variables as patients’ disease status, treatment purpose, treatment regimen natures, and preferences of the providers or patients in the practice of treatment modification.

METHODS

We have established a prospective registry to observe the treatment patterns of patients with cancer undergoing treatment who may or may not have had a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 during the pandemic at the Maimonides Cancer Center. The project was approved by the institutional review board.

Patient Identification

Consecutive patients whose names were present on the cancer center daily chemotherapy schedule between March 9, 2020, and April 10, 2020, were compiled after removing redundant entries. Patients who belonged to the selected six of 10 medical oncology attending physicians in the cancer center were enrolled in this study. Eligible patients should be receiving active treatment. Those patients who only received transfusion of blood products or who needed mediport maintenance flushes were not eligible. Patients who were on active treatment of benign hematologic conditions were eligible, whereas patients who had suspicious or confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 infection were excluded.

Data Collection

Patient demographics were extracted from electronic medical records. The senior author (Y.X.) interviewed each of the five medical oncologists to gather the following information on every patient: cancer type; nature of treatment and status of disease: metastatic, adjuvant or primary treatment; treatment regimen; modification(s) made; who—provider or patient—initiated the modifications; and the reason for not offering modifications, if applicable. Data were verified from the electronic medical records.

Definitions of Treatment Regimens by Potential Adverse Effects

Myelosuppressive regimens included all routine chemotherapy drugs. Nonmyelosuppressive regimens included drugs without myelosuppressive potential, mainly antibodies, such as trastuzumab, bevacizumab, or oral targeted therapies, such as osimertinib. Immunosuppressive drugs included rituximab, lenalidomide, high-dose corticosteroids, and daratumumab. Immune-modulating agents included the immune checkpoint inhibitors that target programmed death 1 or programmed death ligand 1, such as pembrolizumab, nivolumab, atezolizumab, and durvalumab. Endocrine therapy included luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone agonists, fulvestrant, tamoxifen, and aromatase inhibitors. Bone-modulatory therapies included zoledronic acid and denosumab. Benign hematology treatments included intravenous iron replacement, erythropoietin, and romiplostim.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

We initially identified 295 patients on the chemotherapy schedule, 13 of which were excluded as a result of a COVID-19 diagnosis. This study is composed of 282 patients; 93 males and 189 females. Median age was 61 years (range, 27-96 years). The patient population represented multiethnic groups, with the majority being Asian Chinese (n = 124; 44%), followed by African Americans (n = 69; 24.5%), and Whites (n = 60; 21.3%). Two hundred forty-six patients were receiving chemotherapy, which included 87 patients (30.9%) receiving adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy (with or without endocrine therapy), 159 patients (56.3%) receiving palliative treatment of metastatic disease (with or without bone-modulating therapy), 25 patients (8.9%) receiving only endocrine therapy or bone-modulating therapy, and 11 patients receiving treatment of nonmalignant purpose (Table 1). The most common cancer type was breast cancer (n = 85; 30.1%), followed by GI (n = 57; 20.2%) and gynecologic (n = 37; 13.1%) cancers.

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics

Treatment Regimens and Modifications

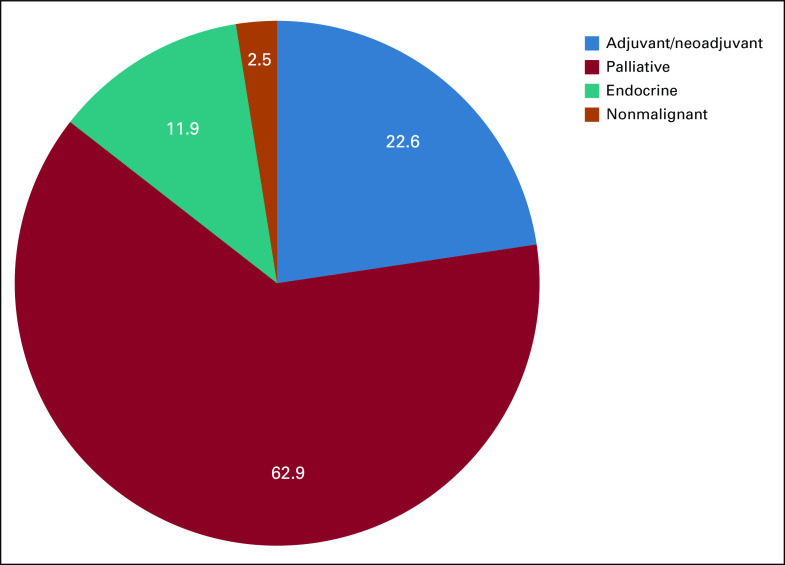

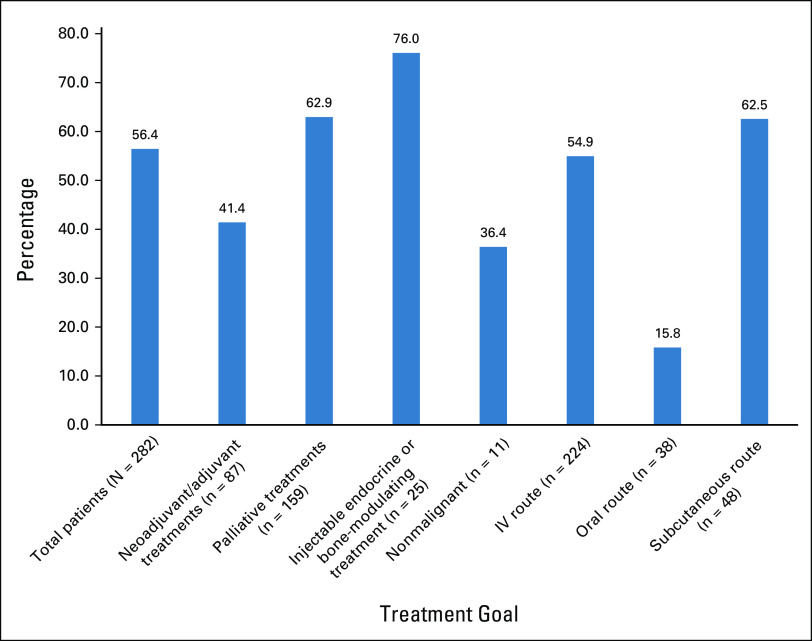

Altogether, the treatments of 159 patients (56.4%) were modified, or 51.8% of the regimens (162 of 313 regimens). Of note, chemotherapy drugs and a targeted oral drug may comprise the regimen of some patients, and the changes may be counted separately in different regimen categories. Median age of patients receiving treatment modification was 64 years, which reflected an older distribution compared with patients who did not have any modification (age 56 years). The majority of those treatment changes fell into the category of palliative. Treatment modifications occurred in all categories divided on the basis of the goals and nature of the treatments (Fig 1) manifesting in 41.4% of the adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings, 62.9% of the palliative setting, and 76.0% of the injectable endocrine or bone-modulating only treatments. Divided by route of administration, these modifications affected intravenous treatments (54.9%) and subcutaneous injectable treatments (62.5%) more than oral treatments (15.8%; Fig 2).

FIG 1.

Prevalence of treatment modifications by the category of nature of treatment. Data are given as percent.

FIG 2.

Incidence of treatment modifications by category of treatment goals and administration routes. IV, intravenous.

Upon breaking down the treatment regimens according to the potential adverse effects (Fig 3), modifications were recommended for patients taking intravenous myelosuppressive therapies (56.5%), intravenous nonmyelosuppressive regimens (46.7%), and immunomodulating and myelosuppressive combination therapies (45.5%). Treatments in the following categories showed a higher chance of needing modification: immunosuppressive (69.2%) and immunomodulating single agent (61.5%). Conversely, oral myelosuppressive treatments (31.6%) and oral nonmyelosuppressive treatments (0%) were less likely to be modified (Fig 3).

FIG 3.

Incidence of treatment modifications by category of potential toxicities with different regimens. IV, intravenous.

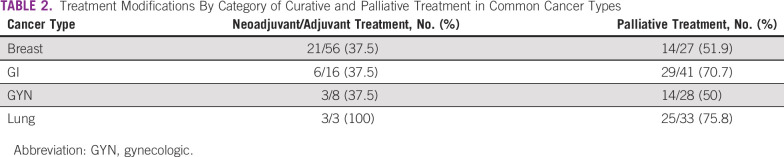

We further analyzed the patterns of changes within each cancer type and individual regimens, and a detailed list of all regimens is provided in the Data Supplement. Data comparing curative with palliative treatment in several selected cancer types are listed in Table 2. Consistently in breast, GI, and gynecologic cancers, treatment modifications were only offered to 37.5% of patients receiving curative treatments, whereas it was offered to more than 50% of patients in palliative treatment cases. In the small subset of patients who were treated for multiple myeloma (n = 10), nine patients had treatment change (90%), and most of the drugs used for this cancer treatment belonged to the category of immunosuppressive drugs (Data Supplement).

TABLE 2.

Treatment Modifications By Category of Curative and Palliative Treatment in Common Cancer Types

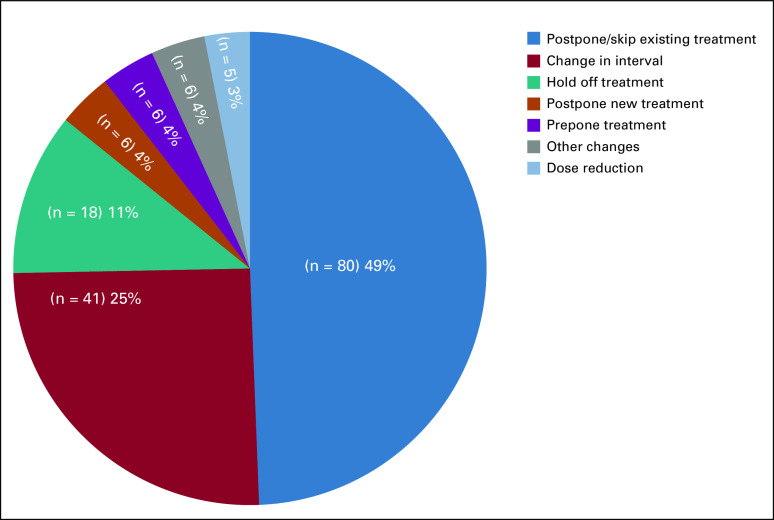

Types of Treatment Regimen Modifications

Seven types of modification strategies were documented (Fig 4), the most common being to postpone or skip an upcoming treatment (n = 80; 49.4%), followed by a change in treatment intervals (n = 41; 25.3%). Four common changes in the latter category were recorded (data not shown) as follows: prolongation of luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone antagonists interval from every month to every 3 months; change of weekly paclitaxel to every 3 weeks; change of weekly gemcitabine and protein-bound paclitaxel used for pancreatic cancer to every 2 weeks; and increased treatment interval of single-agent checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy programmed death ligand 1 inhibitory agents. For 18 patients, it was recommended that treatment be held for an unlimited time. Among this group, median age of patients was 64.5 years (range, 50-87 years). A strategy of dose reduction was occasionally applied, particularly for three patients taking oral poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors, which are known for their myelosuppressive potential. In situations involving surgery as part of the multimodality treatment, six patients had a delay of surgery after the completion of neoadjuvant treatments and were started on hormonal treatment, which was meant to be taken in an adjuvant setting (prepone treatment group).

FIG 4.

Proportion of different types of regimen modification strategies.

Whereas all of the treatment changes were agreed upon by both providers and patients, the changes in 112 patients (70.4%) were recommended by providers and 47 (29.6%) were initiated by patients. Median age of the patients in those two groups was 64 and 65 years, respectively, which does not represent a major difference.

Each health care provider seemed to have a favorable preference in modification strategies, manifested by some by the predominant use of postponing or skipping a cycle of treatment, and by others in favor of increasing intervals (data not shown).

Reasons were also explored for those cases in which treatment regimens were maintained (Fig 5). The most common reason for not changing treatment occurred in patients who have tolerated the treatment well, even in the palliative treatment setting (n = 56; 37.1%). Treatment of symptomatic patients who required palliation from treatment was observed in 22 patients (14.6%).

FIG 5.

Proportion of reasons for no modifications of treatment regimens.

DISCUSSION

Early studies from China indicated that patients with cancer were more likely to have intensive care unit admissions and undergo intubation after contracting COVID-19 infection.2,3 This observation alerted health care providers involved in the care of patients with cancer to exam their practice and recommend individualized cancer treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. New York City, as an epicenter, started to have an exponential surge of cases in early March 2020. At the time, the COVID-19 clinical oncology frequently asked questions published on March 12, 2020, on the ASCO Web site stated that there was no evidence to support changing or holding chemotherapy or immunotherapy in patients with cancer or in bone marrow transplantation/stem-cell transplantation, and withholding critical anticancer or immunosuppressive therapy was not recommended.9 Conversely, the guideline published by the American Society for Breast Surgeons recommended maintaining the treatment plan in patients undergoing curative treatment, as well as in the case of first-line treatment of metastatic disease where patients derive the most benefit.10 Nevertheless, in practice, treatment modifications were made widely among the medical oncology community.

In this study, we aimed to examine the prevalence and factors influencing the decision-making process that led to individualized treatment modifications. We found that treatment modifications were made in more than one half of all patients and in almost all treatment categories, including those of curative and palliative intent. Despite curative intent and contradicting guidelines, treatment modifications were offered to 30% to 40% of patients taking adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatments. Although it is not surprising that treatment modifications were commonly observed in those regimens that may have a negative impact on COVID-19 complications, such as myelosuppressive, immunosuppressive, or immunomodulating treatments, it is surprising to find treatment changes in those with nonmyelosuppressive potential, such as injectable endocrine and bone-modulating treatments. With a close examination of this pattern of treatment modifications, along with data on increased rates of modifications in intravenous and injectable treatments compared with oral treatments, our data show that the primary intention behind modifying treatments was to minimize possible COVID-19 exposure, followed by a secondary goal of reducing treatment-induced toxicities.

The results of the study also provide a glimpse of the negative impact of the pandemic on the decision-making processes of health care providers. We designed the study enrollment period to be 5 weeks between March 9 and April 10, 2020, which reflected a time span when the cumulating cases of COVID-19 were increasing exponentially but had not reached their peak. However, despite being early in the pandemic, as many as 54% of treatment modifications were already planned, with a majority recommended by physicians. Different providers also had their predominant treatment modification strategies. Among them, a simple solution of skipping or postponing a scheduled treatment seemed to be a temporary decision, likely reflecting a day-by-day stress level on the providers from the public health crisis.

Despite the concern of increased morbidity and mortality from COVID-19 infection in patients with cancer, approximately 43.6% of patients continued prescribed treatments without modifications. For patients receiving palliative treatment for metastatic disease, 37.1% (n = 59) continued planned treatment. The American Society for Breast Surgeons guideline also recommended that first-line treatment of metastatic disease be continued as it is likely to improve disease outcome.10,11 In the mind of our providers, continuing treatment in the palliative setting was offered to those who were tolerating treatment well and who were symptomatic. Continuing treatment in those tolerating it well may have implied a perceivable diminished chance of severe myelosuppressive or immunosuppressive toxicities affecting the consequence of COVID-19 infection. Treatment in those who were symptomatic clearly indicated prioritizing and weighing the overall benefits more than the risks in the patient’s disease condition.

Age and comorbidities have also been identified as the most important negative factors for poor outcome from COVID-19 infection.7,12 In our study, the median age of those whose treatment was recommended to be changed was older, indicating that age is an important factor in decision making. In contrast, we did not see a difference in the median age of patients who received treatment modification initiated by providers or by themselves. There were also no differences in the median age of patients who were offered an unlimited break from treatment.

This study provides a real-world snapshot of the response to the COVID-19 threat in a medical oncology community located within a hard-hit area of the pandemic. The advantage of this study is its unbiased patient selection of consecutive patients, which accounts for those who did or did not receive modifications to their treatments. There are also multiple shortcomings of this study. First, there was a disproportionately low representation of certain disease groups, such as hematologic malignancies, lung, and genitourinary cancers, in which decision making may have been different. There was also an underrepresentation of patients taking oral treatments, which can be myelosuppressive/nonmyelosuppressive targeted therapies or hormonal treatments, as they would not appear on the chemotherapy schedule. The selection criteria did not capture newly diagnosed patients who did not start treatment, and no additional information on the decision-making process can thus be obtained. Finally, our study did not follow up on the potential detrimental effects and clinical outcomes of patients who had treatment modifications.

Overall, our study revealed that as many as 56.4% of all patients and approximately 40% of patients taking curative treatments received treatment modifications in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic in our community cancer center. The pattern of modification was best explained by a primary goal of decreasing potential exposure. It also reflected the negative impact of the pandemic on health care providers, who struggled to make right recommendations on an individualized basis incorporating multiple factors, such as tolerance, potential toxicity, nature of the treatment, severity of disease, and route of treatment.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Trishala Meghal, Pooja Murthy, Yiwu Huang, Yiqing Xu

Administrative support: Ashley D’Silva

Provision of study materials or patients: Trishala Meghal, Pooja Murthy, Lan Mo, Yiwu Huang

Collection and assembly of data: Dong D. Lin, Pooja Murthy, Lan Mo, Ashley D’Silva, Yiwu Huang, Yiqing Xu

Data analysis and interpretation: Dong D. Lin, Yiqing Xu

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/site/misc/authors.html.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Yiwu Huang

Consulting or Advisory Role: Rigel, Boehringer Ingelheim

Speakers' Bureau: Takeda, AstraZeneca

Yiqing Xu

Consulting or Advisory Role: Axess Oncology, Eisai, Deciphera, AbbVie

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.New York State Department of Health NYSDOH COVID-19 tracker. https://covid19tracker.health.ny.gov/views/NYS-COVID19-Tracker/NYSDOHCOVID-19Tracker-Map?%3Aembed=yes&%3Atoolbar=no&%3Atabs=n

- 2.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: A nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xia Y, Jin R, Zhao J, et al. Risk of COVID-19 for patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:e180. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30150-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua MLK, et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission in patients with cancer at a tertiary care hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1108–1110. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Report of the WHO-China joint mission on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf

- 7.Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1775–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burki TK. Cancer guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:629–630. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30217-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Society of Clinical Oncology COVID-19 clinical oncology: Frequently asked questions (FAQs) https://www.asco.org/sites/new-www.asco.org/files/content-files/blog-release/pdf/COVID-19-Clinical%20Oncology-FAQs-3-12-2020.pdf

- 10.American College of Surgeons Recommendations for prioritization, treatment and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: Executive summary. doi: 10.1007/s10549-020-05644-z. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/executive-summary [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Dietz JR, Moran MS, Isakoff SJ, et al. Recommendations for prioritization, treatment, and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;181:487–497. doi: 10.1007/s10549-020-05644-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su VYF, Yang Y-H, Yang K-Y, et al. The risk of death in 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Hubei Province. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3539655