Abstract

BACKGROUND

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are found widespread in drinking water, foods, food packaging materials and other consumer products. Several PFAS have been identified as endocrine-disrupting chemicals based on their ability to interfere with normal reproductive function and hormonal signalling. Experimental models and epidemiologic studies suggest that PFAS exposures target the ovary and represent major risks for women’s health.

OBJECTIVE AND RATIONALE

This review summarises human population and toxicological studies on the association between PFAS exposure and ovarian function.

SEARCH METHODS

A comprehensive review was performed by searching PubMed. Search terms included an extensive list of PFAS and health terms ranging from general keywords (e.g. ovarian, reproductive, follicle, oocyte) to specific keywords (including menarche, menstrual cycle, menopause, primary ovarian insufficiency/premature ovarian failure, steroid hormones), based on the authors’ knowledge of the topic and key terms.

OUTCOMES

Clinical evidence demonstrates the presence of PFAS in follicular fluid and their ability to pass through the blood–follicle barrier. Although some studies found no evidence associating PFAS exposure with disruption in ovarian function, numerous epidemiologic studies, mostly with cross-sectional study designs, have identified associations of higher PFAS exposure with later menarche, irregular menstrual cycles, longer cycle length, earlier age of menopause and reduced levels of oestrogens and androgens. Adverse effects of PFAS on ovarian folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis have been confirmed in experimental models. Based on laboratory research findings, PFAS could diminish ovarian reserve and reduce endogenous hormone synthesis through activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, disrupting gap junction intercellular communication between oocyte and granulosa cells, inducing thyroid hormone deficiency, antagonising ovarian enzyme activities involved in ovarian steroidogenesis or inhibiting kisspeptin signalling in the hypothalamus.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS

The published literature supports associations between PFAS exposure and adverse reproductive outcomes; however, the evidence remains insufficient to infer a causal relationship between PFAS exposure and ovarian disorders. Thus, more research is warranted. PFAS are of significant concern because these chemicals are ubiquitous and persistent in the environment and in humans. Moreover, susceptible groups, such as foetuses and pregnant women, may be exposed to harmful combinations of chemicals that include PFAS. However, the role environmental exposures play in reproductive disorders has received little attention by the medical community. To better understand the potential risk of PFAS on human ovarian function, additional experimental studies using PFAS doses equivalent to the exposure levels found in the general human population and mixtures of compounds are required. Prospective investigations in human populations are also warranted to ensure the temporality of PFAS exposure and health endpoints and to minimise the possibility of reverse causality.

Keywords: perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), ovary, folliculogenesis, steroidogenesis

Introduction

According to the definition adopted by the Endocrine Society Scientific Statement, an endocrine-disrupting chemical (EDC) is ‘a compound, either natural or synthetic, which, through environmental or inappropriate developmental exposures, alters the hormonal and homeostatic systems that enable the organism to communicate with and respond to its environment’ (Diamanti-Kandarakis et al., 2009). A variety of EDCs are used in industrial and consumer applications, such as solvents and lubricants (e.g. polychlorinated biphenyls), flame retardants (e.g. polybrominated diethyl ethers), pesticides (e.g. dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane and chlorpyrifos) and plasticisers (e.g. phthalates and bisphenol-A) (Burger et al., 2007; Caserta et al., 2011). Among them, perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have received unprecedented attention recently due to nationwide drinking water contamination and widespread use that impacts up to 110 million residents in the USA (Environmental Working Group, 2018).

PFAS comprise a large family of manmade fluorinated chemicals that are ubiquitous environmental toxicants to which humans are exposed on a daily basis (Trudel et al., 2008). At least one type of PFAS chemical was detected in the blood of nearly every person sampled in the US National Biomonitoring Program (CDC, 2019). Specific members of this family of chemicals are found in many consumer products, such as non-stick cookware (Teflon) (Bradley et al., 2007; Sinclair et al., 2007), food packaging materials (Begley et al., 2005; Trier et al., 2011; Schaider et al., 2017), stain- and water-resistant coating for clothing, furniture and carpets (Scotchgard and GoreTex) (Hill et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2017) and cosmetics and personal care products (Danish EPA, 2018; Boronow et al., 2019). PFAS are also present in fire-fighting foams (or aqueous film-forming foam, AFFF) widely used in military bases for crash and fire training (Butenhoff et al., 2006; Trudel et al., 2008; Kantiani et al., 2010; Kissa, 2011).

Because PFAS are remarkably widespread in drinking water and groundwater in the USA and globally, especially on and near industrial sites, fire-fighting facilities and military installations, they pose a serious and immediate threat to the communities where the source of drinking water has been contaminated with PFAS. Although government and regulatory bodies have been working towards regulations that limit the production of perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), the two primary PFAS compounds that have been the most extensively manufactured (USEPA, 2016a, 2016b), the phase-out and ban of PFOA and PFOS have led to an increased usage of alternative PFAS chemicals (Ateia et al., 2019). Consequently, there is an urgent need to raise the awareness of the potential threat of PFAS to human health.

PFAS have been identified as contaminants of concern for reproductive toxicity (Jensen and Leffers, 2008). Observational studies have shown that PFAS exposure could delay menarche (Lopez-Espinosa et al., 2011), disrupt menstrual cycle regularity (Zhou et al., 2017), cause early menopause (Taylor et al., 2014) and premature ovarian insufficiency (Zhang et al., 2018) and alter the levels of circulating sex steroid hormones (Barrett et al., 2015). The ovary is the site of folliculogenesis and is responsible for the proper maturation of oocytes. It is also the principle site of sex hormone steroidogenesis. Experimental studies have shown that PFAS exposure is associated with the depletion of ovarian reserve (i.e. the number of ovarian follicles and oocytes) (Bellingham et al., 2009; Domínguez et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2015, 2017; Chen et al., 2017; Du et al., 2019; Hallberg et al., 2019; López-Arellano et al., 2019) and inhibition steroidogenic enzyme activities (Shi et al., 2009; Chaparro-Ortega et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018a). Disruption of this finely controlled network may have physiologic impacts beyond the reproductive system, affecting the overall health of girls and women.

Growing evidence has suggested that the ovaries may be a potential target for PFAS toxicity; however, a comprehensive review of experimental and human studies for the effects of PFAS on normal ovarian function has not previously been reported. In this review, we summarise the sources and pathways of PFAS, describe the processes of ovarian folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis, review the state of the science regarding associations between PFAS exposures and ovarian function in experimental and epidemiological studies, identify gaps in the current data and outline directions for future research.

Methods

A thorough search was carried out for relevant articles in order to ensure a comprehensive review on PFAS exposure and ovarian function. We searched PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) through August 2019. The search terms used included PFAS search terms (perfluoroalkyl, polyfluoroalkyl, perfluorinated, fluorocarbons, perfluorobutanoic acid, perfluoropentanoic acid, perfluorohexanoic acid, perfluoroheptanoic acid, perfluorooctanoic acid, perfluorononanoic acid, perfluorodecanoic acid, perfluoroundecanoic acid, perfluorododecanoic acid, perfluorobutane sulfonic acid, perfluorohexane sulfonic acid, perfluoroheptane sulfonic acid, perfluorooctane sulfonic acid, perfluorooctane sulfonamide, PFBA, PFPeA, PFHxA, PFHpA, PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, PFUnDA, PFDoA, PFBS, PFHxS, PFHpS, PFOS, and PFOSA) and outcome search terms (ovary, follicle, oocyte, menarche, menstrual cycle, menopause, primary ovarian insufficiency, premature ovarian failure, steroid hormones, polycystic ovarian syndrome and ovarian cancer). In addition, we manually reviewed the reference lists of identified articles.

Basic Principles of PFAS

Nomenclature

The term PFAS refers to perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, a large group of manmade chemicals with the distinguishing structure of a chain of carbon atoms (forming an ‘alkyl’) that has at least one fluorine atom bound to a carbon. Details of PFAS terminology, classification and origins can be found elsewhere (Buck et al., 2011; Interstate Technology Regulatory Council, 2017). Note that use of non-specific acronyms, such as perfluorinated compound (PFC), should be avoided in the scientific publications as it has hampered clear communications in researchers, practitioners, policymakers and the public.

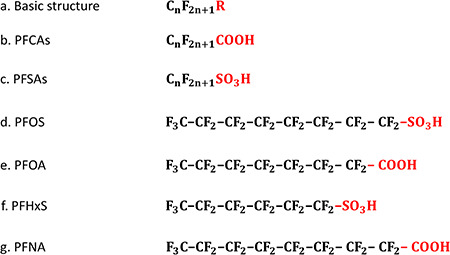

Perfluoroalkyl substances are fully fluorinated molecules in which every hydrogen atom bonded to a carbon in the alkane backbone (carbon chain) is replaced by a fluorine atom, except for the carbon at one end of the chain that has a charged functional group attached. The carbon–fluorine bond is extremely strong and renders these chemicals highly resistant to complete degradation. The basic chemical structure of perfluoroalkyl substances can be written as  , where ‘

, where ‘ ’ defines the length of the perfluoroalkyl chain tail with n > 2, and ‘

’ defines the length of the perfluoroalkyl chain tail with n > 2, and ‘ ’ represents the attached functional group head (as shown in Fig. 1). PFOA and PFOS (so-called C8 compounds) have been the most extensively produced and studied PFAS homologues. Perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) are some of the most basic PFAS molecules and are essentially non-degradable. PFAAs contain three major groups on the basis of the functional group at the end of the carbon chain: perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs), perfluoroalkane sulfonic acids (PFSAs) and perfluoroalkyl phosphonates (PFPAs) or perfluoroalkyl phosphinates (PFPiAs).

’ represents the attached functional group head (as shown in Fig. 1). PFOA and PFOS (so-called C8 compounds) have been the most extensively produced and studied PFAS homologues. Perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) are some of the most basic PFAS molecules and are essentially non-degradable. PFAAs contain three major groups on the basis of the functional group at the end of the carbon chain: perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs), perfluoroalkane sulfonic acids (PFSAs) and perfluoroalkyl phosphonates (PFPAs) or perfluoroalkyl phosphinates (PFPiAs).

Figure 1.

The chemical structures of perfluoroalkyl substances. a. The basic chemical structure of perfluoroalkyl substances, where ‘ ’ represents the length of the perfluoroalkyl chain and ‘

’ represents the length of the perfluoroalkyl chain and ‘ ’ defines the functional group. c. The general chemical structures of perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs) with the functional group of –COOH. d. The general chemical structures of perfluoroalkane sulfonic acids (PFSAs) with the functional group of –

’ defines the functional group. c. The general chemical structures of perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs) with the functional group of –COOH. d. The general chemical structures of perfluoroalkane sulfonic acids (PFSAs) with the functional group of – . d–g. The chemical structures of commonly detected perfluoroalkyl substances, including perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorooctane carboxylic acid (PFOA), perfluohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS) and perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA).

. d–g. The chemical structures of commonly detected perfluoroalkyl substances, including perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorooctane carboxylic acid (PFOA), perfluohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS) and perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA).

Polyfluoroalkyl substances differ from perfluoroalkyl substances by the degree of fluorine substitution in the alkane backbone: at least one carbon must not be bound to a fluorine atom and at least two carbons must be fully fluorinated. The fluorotelomer substances are a subset of polyfluoroalkyl substances because they are oligomers with low molecular weight produced by a telomerisation reaction. Some important examples of fluorotelomer substances are fluorotelomer alcohol (FTOH) and perfluorooctane sulfonamidoethanol (FOSE). Since polyfluoroalkyl substances have a carbon that is lacking fluorine substitution, this weaker bond increases potential for degradation (Buck et al., 2011). For example, FTOH and FOSE can be transformed biologically or abiotically to PFOA and PFOS.

In addition to the descriptions above, PFAS can also exist as polymers. These PFAS polymers are large molecules formed by joining many identical small PFAS monomers. Current information indicates that the non-polymer PFAS constitute the greatest risk for environmental contamination and toxicity, although some PFAS polymers can be degradable to basic PFAS.

Sources of human exposure

Previous studies have evaluated daily exposure in populations around the world (Fromme et al., 2007; Tittlemier et al., 2007; Ericson et al., 2008; Trudel et al., 2008; Ostertag et al., 2009; Haug et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010; Renzi et al., 2013; Heo et al., 2014). Although it is difficult to compare concentrations among populations because of differences in participant characteristics (e.g. age, sex and geographical locations), the ranges of PFAS serum concentrations are remarkably similar worldwide. Exposure to PFAS in the general population is at lower levels compared to those affected by occupational exposure or local contaminations (ATSDR, 2018). Multiple sources of potential exposure to PFAS have been previously identified in the general population. These sources include diet (Tittlemier et al., 2007; Trudel et al., 2008; Vestergren and Cousins, 2009; Haug et al., 2011a; Domingo and Nadal, 2017), drinking water (Post et al., 2009; Thompson et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2016; Domingo and Nadal, 2019), air and dust (Piekarz et al., 2007; Haug et al., 2011b; Goosey and Harrad, 2012; Fromme et al., 2015; Karásková et al., 2016) and consumer products (Begley et al., 2005; Bradley et al., 2007; Sinclair et al., 2007; Trier et al., 2011; Hill et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2017; Schaider et al., 2017; Boronow et al., 2019). The widespread production of PFAS, their use in common commercial and household products, their improper disposal and their resistance to degradation have led to daily human exposures via oral ingestion, inhalation and dermal contact. Different sources and pathways of human exposure are summarised in Table I.

Table I.

Sources and pathways of human exposure to PFAS.

| Sources | Pathways |

|---|---|

| Dietary sources | |

| Fish and shellfish | Environment/Ingestion |

| Drinking water | Ingestion |

| Food-packaging materials | Ingestion |

| Non-stick cookware | Ingestion |

| Others (including dairy products, eggs, beverages and vegetables) | Ingestion |

| Non-dietary sources | |

| Indoor air | Inhalation |

| Indoor dust | Inhalation/ingestion |

| Soil and sediment | Environment |

| Impregnation spray (for furniture and carpet) | Inhalation/dermal absorption |

| Cosmetics | Dermal absorption |

| Other consumer products (including skin waxes, leather samples andoutdoor textiles) | Dermal absorption |

The highest exposures to PFAS are often from dietary intake, particularly to PFOS and PFOA (Tittlemier et al., 2007; Trudel et al., 2008; Vestergren and Cousins, 2009; Haug et al., 2011a; Domingo and Nadal, 2017). Fish and shellfish generally exhibit the highest PFAS concentrations and detection rates among all types of foodstuffs (Domingo and Nadal, 2017; Jian et al., 2017). Other potential dietary sources of PFAS include dairy products, eggs, beverages and vegetables (Haug et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010; Noorlander et al., 2011; Domingo et al., 2012; Eriksson et al., 2013; Herzke et al., 2013; Felizeter et al., 2014; Heo et al., 2014; Gebbink et al., 2015; Vestergren et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2018). However, these foodstuffs have generally low concentrations and low detection frequencies compared to fish and shellfish (Jian et al., 2017). In addition, food can become contaminated with PFAS through transfer from food packaging and/or processing (Schaider et al., 2017) because PFAS are used as in grease- and water-repellent coatings for food-contact materials and non-stick cookware (Begley et al., 2005).

Drinking water is also a common source of PFAS in humans (Domingo and Nadal, 2019). A number of studies have detected PFAS in drinking water samples collected from various countries (Takagi et al., 2008; Jin et al., 2009; Mak et al., 2009; Quinete et al., 2009; Quiñones and Snyder, 2009; Wilhelm et al., 2010; Thompson et al., 2011; Boone et al., 2019). Recently, Boone et al. measured concentrations in source (untreated) and treated drinking water sampled from 24 states across the USA (Boone et al., 2019): Seventeen PFAS analytes were detected in all samples, and summed concentrations ranged from <1–1102 ng/L, with one drinking water treatment plant (DWTP) exceeding the health advisory of 70 ng/L for PFOA and PFOS set by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA).

Some PFAS polymers such as FTOHs were frequently used for impregnation treatment of furniture and floor coverings and as intermediates in manufacturing various household products (e.g. paints, carpet and cleaning agents). These neutral PFAS, mainly FTOHs, FOSA and FOSEs, are volatile compounds that are easily released into indoor environments (air and dust) due to their low water solubility and high vapour pressure (Langer et al., 2010; Haug et al., 2011b; Yao et al., 2018). Perfluoroalkyls have also been detected in indoor air and dust (Kubwabo et al., 2005; Barber et al., 2007; Strynar and Lindstrom, 2008). In the study of 67 houses in Canada, carpeted homes had higher concentrations of PFOA, PFOS and PFHxS in dust, possibly due to the use of stain-repellent coatings (Kubwabo et al., 2005). The use of aqueous firefighting foams at military installations and the production of fluorochemicals at industrial facilities have resulted in widespread contamination in soil and sediment (Xiao et al., 2015; Anderson et al., 2016). Many consumer products, such as ski waxes, leather samples, outdoor textiles and cosmetics products including hair spray and eyeliner, also contain PFAS (Kotthoff et al., 2015; Danish EPA, 2018).

Previous literature has estimated the relative contributions of different exposures routes of PFOA and PFOS in adults (Trudel et al., 2008; Vestergren and Cousins, 2009; Haug et al., 2011a; Lorber and Egeghy, 2011; Gebbink et al., 2015). Oral ingestion from diet and drinking water has been proposed as the largest source of exposure to PFOA and PFOS (around 90%) compared with inhalation or dermal contact (Vestergren and Cousins, 2009; Haug et al., 2011a; Lorber and Egeghy, 2011; Gebbink et al., 2015). For PFOA, Trudel et al. reported ingestion of food from PFOA-containing packaging materials (56%), inhalation of indoor air and dust (14%) and hand-to-mouth transfer of house dust (11%), as significant pathways (Trudel et al., 2008). Other pathways proposed to be less important included ingestion of food prepared with PTFE-coated cookware, dermal contact from clothes and other consumer products (Trudel et al., 2008).

Transport and clearance of PFAS in the human body

Whereas most persistent organic pollutants, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and brominated flame retardants (BFRs), are lipophilic, the substitution of carbon–hydrogen bonds for the strongest carbon–fluorine counterparts coupled with a charged functional group confers unique dual hydrophobic and lipophobic surfactant characteristics to PFAS molecules (Banks and Tatlow, 1994; Kissa, 2011). Most of the available data on transport and clearance of PFAS is based on studies with PFAAs (primarily PFOA and PFOS). In contrast to other persistent organic pollutants, PFAAs are not stored in adipose tissue but undergo extensive enterohepatic circulation. The presence of PFAAs has been confirmed primarily in liver and serum (Pérez et al., 2013; Falk et al., 2015).

The hydrophobic nature of fluorine-containing compounds can also lead to increased affinity for proteins (Jones et al., 2003). Once consumed, PFAAs tend to partition to the tissue of highest protein density, with ~90 to 99% of these compounds in the blood bound to serum albumin (Ylinen and Auriola, 1990; Han et al., 2003). Due to the ability of albumin to pass the blood follicle barrier (Hess et al., 1998; Schweigert et al., 2006), it is suggested that PFAAs can easily be transported into growing follicles. PFAAs have been detected in human follicular fluid and could alter oocyte maturation and follicle development in vivo (Petro et al., 2014; Heffernan et al., 2018).

The primary route of elimination of PFAAs is through the kidney in the urine (Han et al., 2008). Other important clearance pathways include menstruation (Harada et al., 2005; Taylor et al., 2014; Park et al., 2019; Ding et al., 2020), pregnancy (Monroy et al., 2008) and lactation (Bjermo et al., 2013). Sex hormones have been identified as a major factor in determining the renal clearance of PFAAs. One study examined the role of sex hormones and transport proteins on renal clearance and observed that, in ovariectomised female rats, oestradiol could facilitate the transport of PFAAs across the membranes of kidney tubules into the glomerular filtrate, resulting in lower serum concentrations (Kudo et al., 2002).

Serum concentrations of PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS and PFNA appear to be higher in males than in females across all age groups (Calafat et al., 2007). It has been found that ~30% of the PFOS elimination half-life difference between females and males is attributable to menstruation (Wong et al., 2014a). The differences by sex narrows with aging, suggesting that PFAS may reaccumulate after cessation of menstrual bleeding in postmenopausal women (Wong et al., 2014b; Dhingra et al., 2017; Ruark et al., 2017). Decreased serum concentrations have also been shown in premenopausal versus postmenopausal women and, analogously, in men undergoing venesections for medical treatment (Lorber et al., 2015).

PFAAs are considered metabolically inert and remain in the human body for many years. Estimation of human elimination half-lives (or population halving time) for PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS and PFNA have been reported in previous studies (Olsen et al., 2007, 2012; Spliethoff et al., 2008; Bartell et al., 2010; Brede et al., 2010; Glynn et al., 2012; Yeung et al., 2013a, 2013b; Zhang et al., 2013; Wong et al., 2014a; Worley et al., 2017; Eriksson et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018; Ding et al., 2020). Comparing the estimated half-lives of PFAS among populations is difficult as they differ by sampling time intervals, duration of exposure, sex and age of study subjects. Despite these challenges, most of the aforementioned studies have reported that the half-life in humans of PFOA is around 2–3 years and that of PFOS is ~4–5 years.

Mechanistic Evidence for Ovarian Toxicity of PFAS

Effects of PFAS on folliculogenesis

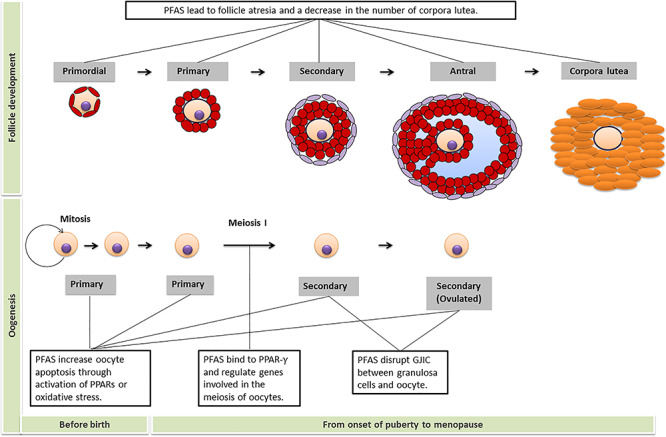

The ovary is the female gonad and an important endocrine organ. The ovaries consist of a surface epithelium surrounding the ovary, a dense underlying connective tissue (tunica albuginea), an outer cortex and an inner medulla. The cortex appears dense and granular due to the presence of ovarian follicles, corpora lutea and stroma. The medulla is highly vascular with abundant blood vessels, lymphatic vessels and nerves. The main functions of the ovary include production, maturation and release of the female gamete (oocyte), and synthesis of female sex steroid and peptide hormones that regulate reproductive and non-reproductive function. Environmental exposures can exhaust the oocyte pool and cause depletion of follicular cells, leading to earlier age at menopause, premature ovarian failure and infertility (Vabre et al., 2017). The processes of oogenesis and follicle development, and the effects of PFAS exposure on folliculogenesis, are summarised in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

PFAS disrupt folliculogenesis. The upper part of the figure is about follicle development and the text box shows the effects of PFAS on the number of follicles at that stage of development. The part below displays the process of oogenesis and text boxes outline the major effects of PFAS at that stage of oocyte development and maturation. GJIC = gap junction intercellular communication; PPAR = peroxisome proliferator activated receptor.

Effects of PFAS on oogenesis

PFAS exposure has been shown to disrupt the earliest stage of folliculogenesis by altering oocyte development (Domínguez et al., 2016; Hallberg et al., 2019; López-Arellano et al., 2019). The potential mechanisms include activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) signalling pathways, disruption of intercellular communication between oocytes and granulosa cells and induction of oxidative stress.

PPARs are family of nuclear hormone receptors that have been identified as key players in the mode of action for PFAS-induced reproductive toxicity (Desvergne and Wahli, 1999). All three known PPAR family members, α, β/δ and γ, are expressed in the ovary (Dauça et al., 2014). The PPAR-α and PPAR-β/δ isoforms are expressed primarily in thecal and stromal cells in the ovary, while the PPAR-γ isoform is detected strongly in granulosa cells and the corpus lutea (Komar et al., 2001). The ability of PFAS to interact with nuclear PPARs has been put forward as an explanation for metabolic disturbances associated with PFAS exposure, mainly through PPAR-α. In addition, PPAR-γ has been found to inhibit the expression of genes involved in the meiosis of oocytes (e.g. endothelin-1 and nitric oxide synthase) (Komar, 2005), implicating a role in female gamete development.

A recent study reported that administration of 10 μg/mL PFNA on bovine oocytes in vitro for 22 h has a negative effect on oocyte developmental competence during their maturation (Hallberg et al., 2019). This decrease in oocyte survival was attributed to PPAR-α(Hallberg et al., 2019), leading to the disturbance of lipid metabolism and increased lipid accumulation in the ovaries (Bjork and Wallace, 2009; Wang et al., 2012). Lending further support, another study showed that excessive lipids in the ooplasm correlated with impaired oocyte developmental competence and low oocyte survival rates (Prates et al., 2014). Because PFAS can bind and activate PPARs and play an important role in PPAR signalling during ovarian follicle maturation and ovulation, it is plausible that persistent activation of ovarian PPARs through PFAS exposure could disrupt the ovarian cell function and oocyte maturation.

In addition to the impact on PPAR signalling, PFAS exposure could alter cell–cell communication within a follicle. Because the interior of an ovarian follicle is avascular, cell–cell communication among granulosa cells and between granulosa cells and the oocyte is critically dependent on bidirectional transfer of low molecular weight nutrients, signalling molecules and waste products via gap junction intercellular communication (Clark et al., 2018). When treated with an aqueous solution with 0, 12.5, 25 and 59 μM PFOS in vitro for a 44-h maturation period, the number of live oocytes and the percentage of matured oocytes decreased in porcine ovaries (Domínguez et al., 2016). Similarly, foetal murine oocytes exposed to 28.2 and 112.8 μM PFOA in vitro for 7 days exhibited increased apoptosis and necrosis (López-Arellano et al., 2019). These effects are attributed due to inhibition of gap junction intercellular communication between oocytes and granulosa cells (Domínguez et al., 2016; López-Arellano et al., 2019).

PFAS may also induce oxidative stress with increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, increased DNA damage and decreased total antioxidant capacity (Wielsøe et al., 2015). Pregnant mice administered 10 mg PFOA/kg/day from gestational days 1–7 or 1–13 exhibited inhibited superoxide dismutase and catalase activity, increased generation of ROS and increased expression of p53 and Bax proteins (important in apoptotic cell death) in the maternal ovaries (Feng et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2017; Xie et al., 2017). Similarly, another study reported significantly increased ROS production in rats exposed to PFOA, which interfered with the activities of complexes I, II and III in the mitochondrial respiratory chain and led to oocyte apoptosis (Mashayekhi et al., 2015; López-Arellano et al., 2019).

Effects of PFAS on follicle development

Studies in laboratory rodents indicate that PFAS alters the formation and/or function of ovarian follicular cells at several stages of development. Adult female mice exposed to 0.1 mg PFOS/kg/day by gavage for 4 months had a decreased number of preovulatory follicles and increased number of atretic follicles (Feng et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2017). Moreover, the PFOS-exposed mice had depressed serum levels of oestradiol and progesterone. Notably, PFOS reduced the mRNA expression of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (Star), which codes for the StAR protein that transports cholesterol from the outer to the inner mitochondrial membrane, a critical step in steroid hormone biosynthesis: this effect on Star was proposed as the cause of deficits in follicle maturation and ovulation (Feng et al., 2015). Similar findings were reported for pregnant mice exposed to 2.5, 5 and 10 mg PFOA/kg/day from gestational days 1–7 or 1–13, with decreased number of corpora lutea accompanied by decreased mRNA expression of Star in the maternal ovaries (Feng et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2017).

In female rats exposed as neonates to 0.1 and 1 mg PFOA/kg/day or 0.1 and 10 mg PFOS/kg/day, there was a significant reduction in the number of ovarian primordial follicles, growing follicles and corpora lutea (Du et al., 2019). The ovarian effects of the prior study were accompanied by down-regulated mRNA expression of KiSS-1 metastasis-suppressor (Kiss1) and KISS1 receptor (Kiss1r) and a decrease in kisspeptin fibre intensities in the hypothalamus. Because kisspeptin signalling has a critical role in regulation of the ovarian cycle as well as initiation of puberty (Gaytán et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2017), the PFOA and PFOS perturbation of follicular development may have resulted from disruption of kisspeptin signalling in the hypothalamus (Bellingham et al., 2009; Du et al., 2019).

Pregnant mice administered oral doses of 200 and 500 mg/kg/day of perfluorobutane sulfonate (PFBS) on Days 1–20 of gestation gave birth to female offspring that exhibited numerous symptoms of disrupted ovarian function: depressed ovarian size and weight, depressed size and weight, decreased number of ovarian follicles (all stages), delayed vaginal opening, delayed onset of oestrus, prolonged diestrus and reduced serum levels of oestradiol (Feng et al., 2017). In addition, the PFBS exposure disrupted thyroid hormone synthesis consistent with hypothyroxinemia, as indicated by depressed serum levels of the thyroid hormones triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) in the dams on gestation day 20 as well as in the female offspring (Feng et al., 2017). Mounting evidence from animal (Lau et al., 2003; Thibodeaux et al., 2003; Chang et al., 2008) and human studies (Dallaire et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2014) suggests that levels of thyroid hormones decrease with increased PFAS concentrations. Thyroid hormones play a critical role in ovarian follicular development and maturation as well as in the maintenance of other physiological functions (Wakim et al., 1994; Fedail et al., 2014). It is possible that thyroid hormone insufficiency could affect follicle development via an influence on the production of follicular fluid inhibin, oestrogens and other cytokines (Dijkstra et al., 1996; Tamura et al., 1998).

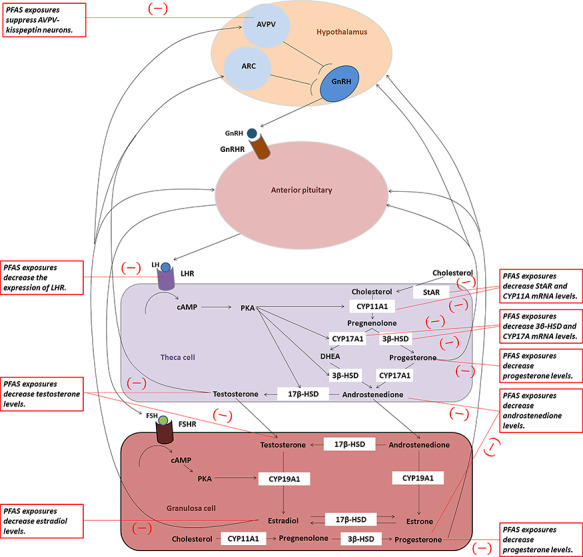

Effects of PFAS on ovarian steroidogenesis

Another primary function of the ovary is ovarian steroidogenesis, i.e. the production and secretion of sex steroid hormones. Ovarian steroidogenesis relies on a strict coordination of both theca cells and granulosa cells and the addition of hypothalamus and anterior pituitary gland (as shown in Fig. 3) (Hillier et al., 1994).

Figure 3.

PFAS alter ovarian steroidogenesis. Ovarian steroidogenesis requires the cooperative interactions of the theca and granulosa cells within the follicles. This figure is a simplified overview of the two-cell ovarian steroidogenesis model, with black text boxes indicating PFAS targets from the experimental literature. ARC = arcuate nucleus; AVPV = anteroventral periventricular nucleus; cAMP = cyclic adenosine monophosphate; CYP11A1 = cholesterol side chain cleavage enzyme; CYP17A1 = 17α-hydroxylase-17, 20-desmolase; CYP19A1 = cytochrome P450 aromatase; ERα = oestrogen receptor α; FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone; FSHR = follicle-stimulating hormone receptor; GnRH = gonadotropin-releasing hormone; GnRHR = gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor; 3β-HSD = 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; 17β-HSD = 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; LH = luteinising hormone; LHR = luteinising hormone receptor; PKA = protein kinase A; StAR = steroid acute regulatory protein.

Thecal cells produce androgens (androstenedione, A4; and testosterone, T) via the enzyme aromatases. As the precursor to steroidogenesis, cholesterol can be transported to the theca cell cytoplasm via the StAR protein. P450 cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (CYP11A1) then catalyses the conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone. Pregnenolone is then converted to a precursor androgen, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), which involves the enzyme 17α-hydroxylase-17, 20-desmolase (CYP17A1) or progesterone, via 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD). Progesterone and DHEA are then converted to an androgen, A4, via CYP17A1 or 3β-HSD, respectively. The final androgenic steroid produced in the theca cell is T using the enzyme 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD).

A4 and T are androgen end-products of theca cell steroidogenesis and migrate across the basal lamina of the follicle to granulosa cells. In preovulatory follicles, granulosa cells proliferate and undergo differentiation to produce increasingly large amounts of 17β-estradiol (E2). Theca cells contain LH receptors (LHRs), and upon receptor binding, LH stimulates the transcription of theca-derived genes that encode the enzymes required for the conversion of cholesterol to androgens. Granulosa cells contain FSH receptors (FSHRs), and in response to FSH binding, the transcription of granulosa-derived genes that encode the enzymes necessary for the conversion of androgens to oestrogens is stimulated.

Endocrine disruption may occur at the molecular and cellular level by interference with steroid hormone biosynthesis in ovaries (Fig. 3). PFAS can modulate the endocrine system by up- or down-regulation of expression of proteins responsible for cholesterol transport and ovarian steroidogenesis. Oral exposure to PFDoA at 3 mg/kg/day from postnatal day 24 for 28 days significantly down-regulated the mRNA expression of ovarian luteinising hormone/choriogonadotropin receptor (Lhcgr), Star, Cyp11a1 and Hsd17b3 in prepubertal female rats, which led to a decrease in E2 production (Shi et al., 2009). Chronic exposure of adult female rats to PFOS (0.1 mg/kg/day) suppresses biosynthesis of E2 possibly through reduced mRNA expression of Star mediated by reduced histone acetylation (Feng et al., 2015). Given that PFAS exposure does not change the substrate (cholesterol) supply in the ovaries (Rebholz et al., 2016), a decrease in Star mRNA levels might account for a reduction in transport of cholesterol as a necessary precursor for ovarian steroidogenesis.

Another possible mechanism of action of PFAS as endocrine disruptors is through activation of PPARs. Exposure of isolated porcine ovarian cells in vitro to 1.2 μM PFOS or PFOA for 24 h inhibited LH-stimulated and FSH-simulated secretion of progesterone, oestradiol and androstenedione in granulosa cells (Chaparro-Ortega et al., 2018). PPAR-γ can inhibit the expression of aromatase, the enzyme for the conversion of androgens to oestrogens, by disrupting the interaction of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) (Fan et al., 2005). Rak-Mardyla and Karpeta showed that the activation of PPAR-κ caused lower expression and decreased enzymatic activity of CYP17 and 17β-HSD in porcine ovarian follicles (Rak-Mardyła and Karpeta, 2014) and thus decreased levels of progesterone and A4.

PFAS are also known to have weak oestrogenic activity and, as with other weak oestrogens, exposure to a combination of E2, and these compounds produced anti-estrogenic effects (Liu et al., 2007). Studies have reported contradictory results using in vitro screening systems to assay for hormone activity by ER- or AR-mediated transactivation in the human breast adenocarcinoma cell lines MCF-7 and MVLN (Maras et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2012; Kjeldsen and Bonefeld-Jørgensen, 2013; Behr et al., 2018), human adrenal carcinoma cell H295R (Du et al., 2013a; 2013b; Wang et al., 2015; Behr et al., 2018) and human placental choriocarcinoma cell JEG-3 (Gorrochategui et al., 2014), as well as in in vivo testing (Biegel et al., 1995; Du et al., 2013a; Yao et al., 2014). It remains unclear whether PFAS affect oestrogen or androgen receptor signalling at concentrations relevant to human exposure.

Nonetheless, because gonadotropin (GnRH) neurons in the hypothalamus do not express ER, they are regulated by E2 and T primarily from kisspeptin neurons in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) and anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AVPV) which send projections to GnRH neurons (Roa et al., 2009). E2 and T down-regulate Kiss1 mRNA in the ARC and up-regulate its expression in the AVPV. Therefore, kisspeptin neurons in the ARC may participate in the negative feedback regulation of GnRH secretion, whereas kisspeptin neurons in the AVPV contribute to generating the preovulatory GnRH surge in the female. In vivo evidence demonstrated that exposure of adult female mice to PFOS at 10 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks led to diestrus prolongation and ovulation reduction through suppression of AVPV-kisspeptin neurons, but not via ARC-kisspeptin neurons in the forebrain (Wang et al., 2018a). PFAS may impair ovulation and reproductive capacity through suppression of the activation of ER-mediated AVPV-kisspeptin expression.

Epidemiologic Evidence Linking PFAS Exposure and Ovarian Outcomes

Ovarian folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis are essential processes for normal reproductive health. Increasing evidence suggests that PFAS could adversely affect numerous aspects of these processes. Specifically, exposures to PFOA and PFOS have been shown to impact ovarian steroidogenesis (Table II), delay onset of menarche (Table III), disrupt menstrual cycle regularity (Table IV), accelerate ovarian aging (Table V) and may affect other chronic conditions such as polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and ovarian cancer (Table VI). Other PFAS homologues may also have an impact on ovarian function (Table VII).

Table II.

Epidemiologic evidence on the associations of exposure to PFOA and PFOS with sex hormones.

| First author, Year | Study design | Population, location, and time period | Sample size | Age, year | PFOA, ng/mL | PFOS, ng/mL | Inclusion/exclusion criteria | Hormones | Measure of association | Results | Covariate adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knox 2011 | Cross-sectional | Women enrolled in the C8 Health Project from the Mid-Ohio Valley in the US during 2005–2006 | 25 957 | 18–65 | Median 23.6 | Median 17.6 | Excluding pregnant women, women on hormones or medications affecting hormones, women who had hysterectomy | Serum E2, pmol/L |

(P value) stratified by age groups (18–42, >42–51 and >51 years) (P value) stratified by age groups (18–42, >42–51 and >51 years) |

PFOA: no association PFOS: only in women >42–51 years,(−) -13.4 (P < 0.0001); and >51 years, (−) −3.0 (P = 0.007) | Age, BMI, alcohol consumption, smoking, exercise |

| Kristensen, 2013 | Birth cohort | Female offspring enrolled in a Danish population-based cohort from 1988–1989 with follow-ups in 2008–2009 | 267 | ~20 | Median (IQR) maternal exposure 3.6 (2.8–4.8) | Median (IQR) maternal exposure 21.1 (16.7–25.5) | Excluding mothers with breastfeeding, or signs of premature ovarian insufficiency | Serum E2, T, SHBG, DHEA, FSH, LH, and AMH, ln(pmol/L); FAI |

(95%CI) (95%CI) |

No association | Maternal smoking during pregnancy, household income, BMI, smoking status, menstrual cycle phase |

| Barrett, 2015 | Cross-sectional | Healthy women with natural cycling enrolled in the parent Energy Balance and Breast Cancer Aspects study from Norway during 2000–2002 | 178 | 25–35 | Median by parity Nulliparous: 3.4; parous: 2.0 | Median by parity Nulliparous: 14.8; parous: 12.7 | Excluding women with OC use, known histories of infertility gynaecological disorders, or chronic illness (e.g. Type 2 diabetes or hypothyroidism) | Saliva E2 and P, ln(pmol/L) Day −7 to −1 for E2 and day +2 to +10 for P | β (95%CI) stratified by parity | Among nulliparous women, 1) ln(E2) PFOA: no association PFOS:(−) -0.025 (−0.043, −0.007) 2) ln(P) PFOA: no association PFOS:(−) -0.027 (−0.048, −0.007) Among parous women, no association | Age, marital status, BMI, physical activity, history of hormone contraceptives, alcohol consumption, smoking status |

| Lewis, 2015 | Cross-sectional | Women in NHANES 2011–2012 from the US | 824 | 12–80 | Median by age groups 12–<20:1.5; 20–<40:1.5; 40–<60:1.6; 60–<80:2.6 | Median by age groups 12–<20:3.8; 20–<40:4.2; 40–<60:4.9; 60–<80: 9.5 | NA | Serum T, pmol/L | Percent change (95% CI) per doubling increase in PFAS stratified by age groups | No association | Age, BMI, PIR, serum cotinine, race/ethnicity |

| Tsai, 2015 | Cross-sectional | Women recruited from China during 2006–2008 | 330 | 12–30 | Median 3.6 | Median 5.4 | Including adolescent and young adult students | Serum SHBG, FSH, T, and E2 ln(pmol/L) | Predicted mean(SE) in PFAS categories (<median, median-p75, >p75–p90, >p90) stratified by age groups (12–17; 18–30) | Among adolescents, (i) SHBG PFOA: (−) 3.5 (0.2), 3.5 (0.3), 3.4 (0.3), 3.0 (0.3) PFOS: no association (ii) FSH: no association (iii) T PFOA: no association PFOS: (−) 4.0 (0.2), 4.0 (0.2), 3.9 (0.2), 3.6 (0.4) (iv) E2: no association Among young adults, no association | Age, gender, BMI, high-fat diet |

| Lopez-Espinosa, 2016 | Cross-sectional | Girls enrolled in the C8 Health Project during 2005–2006 | 1123 | 6–9 | Median 35 | Median 22 | Excluding girls with menarche | Serum E2 and T, pmol/L | Percent change (95% CI) in the p75 vs. p25 of ln(PFAS) | PFOA: no association PFOS: (−) -6.6% (−10.1%, −2.8%) | Age, time of sampling |

| Zhou, 2016 | Cross-sectional | Girls enrolled in the Genetics and Biomarkers study for Childhood Asthma from China during 2009–2010 | 123 | 13–15 | Median (IQR) 0.5 (0.4–1.2) | Median (IQR) 28.8 (14.8–42.6) | Including girls from seven public schools who had no personal or family history of asthma | Serum E2 and T, pmol/L |

(95%CI) per 1 ng/mL increase in PFAS (95%CI) per 1 ng/mL increase in PFAS |

No association | Age, BMI, ETS exposure, parental education, regular exercise and month of survey |

| McCoy, 2017 | Cross-sectional | Women undergoing IVF in the US during 2013–2014 | 36 | Mean 34 | Plasma, ng/g Mean SD 2.4 SD 2.4 0.3 0.3 |

Plasma, ng/g Median SD 6.5 SD 6.5 0.5 0.5 |

Including women at the Coastal Fertility Center in the Mount Pleasant, South Carolina | Plasma E2, pg/mL | Correlation coefficient (P value) | PFOA: no association PFOS: (−) -0.47 (P < 0.05) | NA |

| Heffernan, 2018 | Case–control | Women with PCOS and age- and BMI-matched controls recruited from the UK in 2015 | 59 | 20–45 | GM (range) 2.4 (0.5–8.2) | GM (range) 3.5 (0.9–7.7) | Including women with BMI  35 and undergoing IVF; excluding those with immunological disease, diabetes, renal insufficiency, infections or inflammatory diseases. 35 and undergoing IVF; excluding those with immunological disease, diabetes, renal insufficiency, infections or inflammatory diseases. |

Serum T, and SHBG, ln(pmol/L); FAI; Serum A4 and E2, pmol/L Luteal phase | β (SE) per ln-unit increase in PFAS stratified by cases and controls | Among PCOS cases, no association. Among controls, (i) ln(T) PFOA: (+) 0.52 (0.15) PFOS: no association (ii) SHBG: no association (iii) ln(FAI) PFOA: no association PFOS: (−) -0.61 (0.26) (iv) A4: no association (v) E2: no association | Serum albumin |

| Zhang, 2018 | Case–control | Women with overt POI and 120 healthy controls from China recruited during 2013–2016 | 240 | 20–40 | Median (IQR) 11.1 (7.6–14.5) | Median (IQR) 8.4 (6.3–11.3) | Excluding women with chromosomal abnormalities, a history of radiotherapy or chemotherapy, ovarian surgery, thyroid-related diseases or use of thyroid medications | Serum FSH, LH, PRL, T and E2, ln(ng/mL) Early follicular phase |

(95%CI) per ln-unit increase in PFAS (95%CI) per ln-unit increase in PFAS |

Among POI cases, (i) ln(FSH) PFOA: no association PFOS: (+) 0.3 (0.2–0.4) (ii) ln(LH): no association (iii) ln(E2) PFOA: no association PFOS: (−) -0.2(−0.4,-0.04) (iv) ln(PRL): PFOA: (+) 0.2 (0.01–0.3) PFOS: (+) 0.2 (0.06–0.3) (v) ln(T): no association Among controls, no association | Age, BMI, education, income, sleep quality, parity |

Abbreviations: AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone; A4, androstenedione; BMI, body mass index; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; ETS, environmental tobacco smoke; E2, estradiol; FAI, free androgen index, was calculated as 100  total T / SHBG; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GM, geometric mean; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not available; NM, not measured; OR, odds ratio; P, progesterone; PCOS, polycystic ovarian syndrome; PFOA, perfluorooctanoic acid; PFOS, perfluorooctane sulfonic acid; POI, premature ovarian insufficiency; PRL, prolactin; p25, 75 and 90, 25th, 75th and 90th percentiles; SHBG, sex hormone-binding globulin; T, testosterone; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

total T / SHBG; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GM, geometric mean; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not available; NM, not measured; OR, odds ratio; P, progesterone; PCOS, polycystic ovarian syndrome; PFOA, perfluorooctanoic acid; PFOS, perfluorooctane sulfonic acid; POI, premature ovarian insufficiency; PRL, prolactin; p25, 75 and 90, 25th, 75th and 90th percentiles; SHBG, sex hormone-binding globulin; T, testosterone; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table III.

Epidemiologic evidence on the associations of exposure to PFOA and PFOS with menarche.

| First author, Year | Study design | Population, location, and time period | Sample size | Age, year | PFOA, ng/mL | PFOS, ng/mL | Outcome | Measure of association | Results | Covariate adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christensen, 2011 | Case–control | Girls with age of menarche before 11.5 years and controls with age of menarche later than 11.5 years from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children conducted during 1991–1992 in the UK | 218 cases and 230 controls | 8–13 | Median (IQR) maternal exposure 3.7 (2.8–4.8) | Median (IQR) maternal exposure 19.8 (15.1–24.9) | Early menarche before age 11.5 years | OR (95% CI) by PFAS dichotomous categories | PFOA/PFOS: no association | Birth order, maternal age at delivery |

| Lopez-Espinosa, 2011 | Cross-sectional | Girls enrolled in the C8 Health Project from the Mid-Ohio Valley in the US during 2005–2006 | 2931 | 8–18 | Median (IQR) 28.2 (11–58) | Median (IQR) 20.2 (14–27) | (i) Being postmenarcheal (ii) Delay in age of menarche, day | OR (95%CI) in the highest quartile vs. the lowest (the reference) | (i) Being postmenarcheal PFOA: (−) 0.57 (0.37–0.89). PFOS: (−) 0.55 (0.35–0.87). (ii) Delay in age of menarche PFOA: 130 days PFOS: 138 days | Age |

| Kristensen, 2013 | Birth cohort | Female offspring enrolled in a Danish population-based cohort from 1988–1989 with follow-ups in 2008–2009 | 267 | ~20 | Median (IQR) maternal exposure 3.6 (2.8–4.8) | Median (IQR) maternal exposure 21.1 (16.7–25.5) | Age of menarche, month |

(95%CI) in the highest tertile vs. the lowest (the reference) (95%CI) in the highest tertile vs. the lowest (the reference) |

PFOA: (+) 5.3 (1.3–9.3) PFOS: no association | Maternal smoking during pregnancy, household income, daughter’s BMI |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio; PFOA, perfluorooctanoic acid; PFOS, perfluorooctane sulfonic acid; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table IV.

Epidemiologic evidence on the associations of exposure to PFOA and PFOS with menstrual cycle characteristics.

| First author, Year | Study design | Population, location, and time period | Sample size | Age, year | PFOA, ng/mL | PFOS, ng/mL | Outcome | Measure of association | Results | Covariate adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fei, 2009 | Cross-sectional | Women with planned pregnancy enrolled in the Danish National Birth Cohort during 1996–2002 | 1240 | Mean 30.6 | Median (IQR) 5.3 (4.0–7.0) | Median (IQR) 33.7 (26.6–43.5) | Self-reported irregular menses | Proportion of women in the lowest vs. the upper three quartiles | PFOA: 9.0 vs. 15.0% PFOS: 11.6 vs. 14.2% | None |

| Kristensen, 2013 | Birth cohort | Female offspring enrolled in a Danish population-based cohort from 1988–1989 with follow-ups in 2008–2009 | 267 | ~20 | Median (IQR) prenatal exposure 3.6 (2.8–4.8) | Median (IQR) maternal exposure 21.1 (16.7–25.5) | (i) Cycle length, day (ii) Number of follicles per ovary |

(95% CI) per ln-unit increase stratified by OC use (95% CI) per ln-unit increase stratified by OC use |

PFOA/PFOS: no association | Maternal smoking during pregnancy, social class, BMI, smoking status. |

| Lyngsø, 2014 | Cross-sectional | Women with planned pregnancy enrolled in the Inuit-Endocrine Cohort during 2002–2004 from Greenland, Poland, and Ukraine | 1623 | 19–49 | Median (p10;90) 1.5 (0.7–3.1) | Median (p10;90) 8.0 (3.6–25.6) | (i) Longer cycle with cycle length  32 days (ii) Shorter cycle with cycle length 32 days (ii) Shorter cycle with cycle length  24 days (iii) Irregular cycle with 24 days (iii) Irregular cycle with  7 days in difference between cycles 7 days in difference between cycles |

OR (95% CI) in the highest tertile vs. the lowest (the reference) | (i) Longer cycle PFOA: (+) 1.8 (1.0–3.3). PFOS: no association (ii) Shorter cycle PFOA/PFOS: no association (iii) Irregular cycle PFOA/PFOS: no association | Age at menarche, age at pregnancy, parity, BMI before pregnancy, smoking, and country |

| Lum, 2017 | Cross-sectional | Female attempting pregnancy enrolled in the Longitudinal Investigation of Fertility and Environment Study during 2005–2009 from the US | 501 | 18–40 | Median 3.2 | Median 12.3 | Relative difference in cycle length | AF (95% CI) in the highest tertile vs. the lowest (the reference) | PFOA: (−) 0.98 (0.96–1.00) PFOS: no association | Age, BMI, smoking status |

| Zhou, 2017 | Cross-sectional | Women who were attempting pregnancy recruited during 2013–2015 from China | 950 | Median (IQR) 30 (28–32) | Median (IQR) 13.8 (10.1–18.8) | Median (IQR) 10.5 (7.6–15.4) | (i) Longer periods with cycle length > 35 days (ii) Irregular periods with  7 days in difference between cycles (iii) Menorrhagia as self-reported heavy or very heavy bleeding (iv) Hypomenorrhea as self-reported light bleeding 7 days in difference between cycles (iii) Menorrhagia as self-reported heavy or very heavy bleeding (iv) Hypomenorrhea as self-reported light bleeding |

OR (95% CI) in the highest quartile vs. the lowest (the reference) | (i) Longer periods PFOA: (+) 2.0 (1.2–3.1). PFOS: no association (ii) Irregular periods PFOA: (+) 2.0 (1.2–3.2). PFOS: no association (iii) Menorrhagia PFOA: (−) 0.2 (0.1–0.5). PFOS: (−) 0.3 (0.1–0.6). (iv) Hypomenorrhea PFOA/PFOS: no association | Age, BMI, income, age at menarche, and parity |

Abbreviations: AF, acceleration factor; BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio; PFOA, perfluorooctanoic acid; PFOS, perfluorooctane sulfonic acid; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table V.

Epidemiologic evidence on the associations of exposure to PFOA and PFOS with ovarian aging.

| First author, Year | Study design | Population, location, and time period | Sample size | Age, year | PFOA, ng/mL | PFOS, ng/mL | Outcome | Measure of association | Results | Covariate adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knox, 2011 | Cross-sectional | Women enrolled in the C8 Health Project from the Mid-Ohio Valley in the US during 2005–2006 | 25 957 | 18–65 | Median 23.6 | Median 17.6 | Natural menopause | OR (95% CI) in the highest quintile vs. the lowest (the reference) stratified by age groups (18–42, >42–51 and >51 years) | 18–42 years PFOA/PFOS: no association >42–51 years PFOA: (+) 1.4 (1.1–1.8) PFOS: (+) 1.4 (1.1–1.8) >51 years PFOA: (+)1.7 (1.3–2.3) PFOS: (+) 2.1 (1.6–2.8) | Age, BMI, alcohol consumption, smoking status, exercise |

| Taylor, 2014 | Retrospective cohort | General adult women in NHANES 1999–2010 from the US | 2732 | 20–65 | Median 3.8 | Median 14.0 | (i) Natural menopause (ii) Hysterectomy | HR (95% CI) in the highest tertile vs. the lowest (the reference) | (i) Natural menopause PFOA: (+) 1.4 (1.1–1.8) PFOS: no association (ii) Hysterectomy PFOA: (+) 2.8 (2.1–3.7) PFOS: (+) 2.6 (1.9–3.4) | Age, race/ethnicity, education, smoking status, parity |

| Dhingra, 2016 | Prospective cohort | Premenopausal women enrolled in the C8 Health Project from the Mid-Ohio Valley in the US during 2005–2006 and followed up during 2008–2011 | 3334 |

40 40 |

P40, 60 17.8–33.6 | NM | Natural menopause | HR (95% CI) in the highest quintile vs. the lowest (the reference) with hysterectomy censored or excluded | No association | Smoking status, education, BMI, parity |

| Zhang, 2018 | Case–control | Women with overt POI and healthy controls from China recruited during 2013–2016 | 240 | 20–40 | Median (IQR) POI cases, 11.1 (7.6–14.5); Controls, 8.4 (6.3–11.3) | Median (IQR) POI cases, 8.2 (5.5–13.5); Controls, 6.0 (4.2–9.1) | POI as an elevated FSH level >25 IU/L on two occasions >4 weeks apart and oligo/amenorrhea for  4 months 4 months |

OR (95% CI) in the highest tertile vs. the lowest (the reference) | PFOA: (+) 3.8 (1.9–7.5) PFOS: (+) 2.8 (1.5–5.4) | Age, BMI, education, income, sleep quality, parity |

Abbreviations: AF, acceleration factor; IQR, interquartile range; NM, not measured; OR, odds ratio; PFOA, perfluorooctanoic acid; PFOS, perfluorooctane sulfonic acid; POI, premature ovarian insufficiency; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table VI.

Epidemiologic evidence on the associations of exposure to PFOA and PFOS with other chronic conditions.

| First author, Year | Study design | Population, location, and time period | Sample size | Age, year | PFOA, ng/mL | PFOS, ng/mL | Outcome | Measure of association | Results | Covariate adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barry, 2013 | Retrospective cohort | Female residents enrolled in the C8 Health Project and workers employed at DuPont from the US during 2005–2006 and followed up in 2008–2011 | 17 360 | Mean 53 | Median (range) for residents 24.2 (0.25–4752), and for workers 112.7 (0.25–22 412) | NM | Ovarian cancer | HR (95% CI) per ln-unit increase in PFAS | No association | Smoking, alcohol consumption, sex, education, birth year |

| Vieira, 2013 | Cross-sectional | Cancer patients living near the DuPont plant from the US during 1996–2005 | 25 107 | Median 67 | Range 3.7–655 estimated based on geocoded address | NM | Ovarian cancer | OR (95% CI) in the highest category (110–655 ng/mL) vs. unexposed group (the reference) | No association | Age, race, sex, diagnosis year, insurance provider, smoking status |

| Wang, 2019a | Case–control | Infertile women diagnosed with PCOS and healthy controls from China in 2014 | 367 | 20–40 | Median 5.1 | Median 4.1 | PCOS | OR (95% CI) in the highest tertile vs. the lowest (the reference) | No association | Age, BMI, household income, education, employment, age at menarche, menstrual volume |

Abbreviations: NM, not measured; OR, odds ratio; PCOS, polycystic ovarian syndrome; PFOA, perfluorooctanoic acid; PFOS, perfluorooctane sulfonic acid; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table VII.

Epidemiologic evidence on the effects of other PFAS homologues.

| First author, Year | Study design | Population, location and time period | Sample size | Age, year | Other PFAS homologues, ng/mL | Outcome | Measure of association | Results | Covariate-adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menarche | |||||||||

| Christensen, 2011 | Case–control | Girls with age of menarche before 11.5 years and controls with age of menarche later than 11.5 years from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children conducted during 1991–1992 in the UK | 448 | 8–13 | Median (IQR) maternal exposure PFOSA, 0.2 (0.2–0.3) EtFOSAA, 0.6 (0.4–0.9) MeFOSAA, 0.4 (0.3–0.8) PFHxS, 1.6 (1.2–2.2) PFNA, 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | Early menarche before age 11.5 years | OR (95% CI) by PFAS dichotomous categories at medians | No association | Birth order, maternal age at delivery |

| Menstrual cycle characteristics | |||||||||

| Zhou, 2017 | Cross-sectional | Women who were attempting pregnancy recruited during 2013–2015 from China | 950 | ~30 | Median (IQR) PFHxS, 0.7 (0.6–0.9) PFNA, 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | (i) Longer cycle with cycle length > 35 days (ii) Irregular cycle with  7 days in difference between cycles (iii) Menorrhagia as self-reported heavy or very heavy bleeding (iv) Hypomenorrhea as self-reported light bleeding 7 days in difference between cycles (iii) Menorrhagia as self-reported heavy or very heavy bleeding (iv) Hypomenorrhea as self-reported light bleeding |

OR (95% CI) in the highest quartile vs. the lowest (the reference) | (i) Longer cycle PFHxS: (+) 2.1 (1.3–3.5) PFNA: (+) 1.7 (1.0–2.7) (ii) Irregular cycle PFHxS: (+) 2.1 (1.3–3.5) PFNA: no association (iii) Menorrhagia PFHxS: (−) 0.3 (0.1–0.7) PFNA: (−) 0.4 (0.2–0.9) (iv) Hypomenorrhea PFHxS: (+) 3.6 (1.5–8.6) PFNA: no association | Age, BMI, income, age at menarche and parity |

| Lum, 2017 | Cross-sectional | Female attempting pregnancy enrolled in the Longitudinal Investigation of Fertility and Environment Study during 2005–2009 from the US | 501 | 18–40 | Median (IQR) among women with normal cycle MeFOSAA, 0.3 (0.1–0.5) PFDA, 0.4 (0.2–0.6) PFNA, 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | Relative difference in menstrual cycle length | AF (95% CI) in the highest tertile vs. the lowest (the reference) | No association | Age, BMI, smoking status |

| Ovarian aging | |||||||||

| Zhang, 2018 | Case–control | Women with overt POI and healthy controls from China recruited during 2013–2016 | 240 | 20–40 | Median (IQR) in controls: PFHpA, 0.2 (0.1–0.3) PFNA, 1.8 (1.3–2.7) PFDA, 1.7 (1.0–2.6) PFDoA, 0.17 (0.1–0.2) PFUnDA, 1.3 (0.8–1.9) PFBS, 0.05 (0.04–0.1) PFHxS, 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | POI as an elevated FSH level > 25 IU/L on two occasions >4 weeks apart and oligo/amenorrhea for  4 months 4 months |

OR (95% CI) in the highest tertile vs. the lowest (the reference) | PFHpA: no association PFNA: no association PFDA: no association PFDoA: no association PFUnDA: no association PFBS: no association PFHxS: (+) 6.6 (3.2–13.7) | Age, BMI, education, income, sleep quality, parity |

| Taylor, 2014 | Retrospective cohort | General adult women in NHANES 1999–2010 from the US | 2732 | 20–65 | Median (IQR) in premenopausal women: PFHxS, 1.0 (0.6–1.8) PFNA, 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | (i) Natural menopause (ii) Hysterectomy | HR (95% CI) in the highest tertile vs. the lowest (the reference) | (i) Natural menopause PFHxS: (+) 1.7 (1.4–2.1) PFNA: (+) 1.5 (1.1–1.9) (ii ) Hysterectomy PFHxS: (+) 3.5 (2.7–4.5) PFNA: (+) 1.8 (1.3–2.4) | Age, race/ethnicity, education, smoking status, parity |

| Sex steroid hormones | |||||||||

| Barrett et al., 2015 | Cross-sectional | Healthy women with natural cycling enrolled in the parent Energy Balance and Breast Cancer Aspects study from Norway during 2000–2002 | 178 | 25–35 | Median (range) in nulliparous women: PFOSA, 0.2 (0.07–1.1) PFHxS, 1.1 (0.3–5.0) PFDA, 0.2 (0.05–2.0) PFUnDA, 0.4 (0.07–1.1) PFNA, 0.6 (0.2–2.9) | Saliva E2 and P, ln(pmol/L) Days −7 to −1 for E2 and Days +2 to +10 for P |

(95%CI) stratified by parity (95%CI) stratified by parity |

No association | Age, marital status, BMI, physical activity, history of hormone contraceptives, alcohol consumption, smoking status |

| Lewis, 2015 | Cross-sectional | Women in NHANES 2011–2012 from the US | 824 | 12–80 | Median by age groups 12–<20:PFHxS, 0.8; PFNA, 0.7; 20–<40:PFHxS, 0.7; PFNA, 0.7; 40–<60:PFHxS, 0.9; PFNA, 0.8; 60–<80:PFHxS, 1.5; PFNA, 1.1. | Serum T, pmol/L | Percent change (95% CI) per doubling increase in PFAS stratified by age groups | No association | Age, BMI, PIR, serum cotinine, race/ethnicity |

| Tsai, 2015 | Cross-sectional | Women recruited from China during 2006–2008 | 330 | 12–30 | Median (IQR) PFUnDA, 6.5 (1.5–13.4) P60, 90 PFNA, 1.6–6.9 | Serum SHBG, FSH, T, and E2 ln(pmol/L) | Predicted mean(SE) in PFAS categories (<median, median-p75, >p75-p90, >p90) stratified by age groups (12–17; 18–30) | Among adolescents, (i) SHBG: no association (ii) FSH PFNA: no association PFUnDA: only in girls 12–17 years, (−) 1.6 (0.3), 1.6 (0.2), 1.4 (0.2), 1.2 (0.2) (iii) T: no association (iv) E2: no association | Age, gender, BMI, high fat diet |

| Lopez-Espinosa, 2016 | Cross-sectional | Girls enrolled in the C8 Health Project during 2005–2006 | 1123 | 6–9 | Median (IQR) PFHxS, 7.0 (3.8–13.8) PFNA, 1.7 (1.3–2.4) | Serum E2 and T, pmol/L | Percent change (95% CI) in the p75 vs. p25 of ln(PFAS) | No association | Age, time of sampling |

| Zhou, 2016 | Cross-sectional | Girls enrolled in the Genetics and Biomarkers study for Childhood Asthma from China during 2009–2010 | 123 | 13–15 | Median (IQR) PFBS, 0.5 (0.4–0.5) PFHxS, 1.2 (0.5–3.0) PFHxA, 0.2 (0.1–0.3) PFNA, 0.9 (0.6–1.1) PFDA, 1.0 (0.8–1.2) PFDoA, 3.1 (0.9–6.2) PFTeA, 4.5 (0.3–18.4) | Serum E2 and T, pmol/L |

(95%CI) per 1 ng/mL increase in PFAS (95%CI) per 1 ng/mL increase in PFAS |

(i) ln(T): Only for PFDoA, (−) -0.012 (−0.023–−0.001) (ii) ln(E2): No association | Age, BMI, ETS exposure, parental education, regular exercise, and month of survey |

| McCoy, 2017 | Cross-sectional | Women undergoing IVF in the US during 2013–2014 | 36 | Mean 34 | Plasma, ng/g Mean  SD PFHxS, 2.2 SD PFHxS, 2.2  0.4 PFNA, 0.8 0.4 PFNA, 0.8  0.1 PFDA, 0.4 0.1 PFDA, 0.4  0.05 PFUnDA, 0.3 0.05 PFUnDA, 0.3  0.03 0.03 |

Plasma E2, pg/mL | Correlation coefficient (P value) | No association | NA |

| Heffernan, 2018 | Case–control | Women with PCOS and age- and BMI-matched controls recruited from the UK in 2015 | 59 | 20–45 | GM (range) PFHxS, 1.0 (0.2–10.2) PFNA, 0.6 (0.2–1.8) | Serum T, and SHBG, ln(pmol/L); FAI; Serum A4 and E2, pmol/L Luteal phase |

(SE) per ln-unit increase in PFAS stratified by cases and controls (SE) per ln-unit increase in PFAS stratified by cases and controls |

Among PCOS cases, only for A4 and PFNA: (+) 1.71 (0.65) Among controls, only for ln(T), PFHxS: (+) 0.50 (0.17) PFNA: (+) 0.46 (0.21) | Serum albumin |

| Zhang, 2018 | Case–control | Women with overt POI and 120 healthy controls from China recruited during 2013–2016 | 240 | 20–40 | Median (IQR) in controls PFHxS, 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | Serum FSH, LH, PRL, T, and E2, ln(ng/mL) Early follicular phase |

(95%CI) per ln-unit increase in PFAS (95%CI) per ln-unit increase in PFAS |

Among POI cases, (i) ln(FSH) (+) 0.16 (0.04–0.28) (ii) ln(LH): no association (iii) ln(E2) (−) -0.19 (−0.37–−0.02) (iv) ln(PRL): no association (v) ln(T): no association Among controls, no association | Age, BMI, education, income, sleep quality, parity |

| Other chronic conditions | |||||||||

| Wang, 2019a | Case–control | Infertile women diagnosed with PCOS and healthy controls from China in 2014 | 367 | 20–40 | Median (IQR) PFBS, 0.11 (0.1–0.12) PFHxS, 0.24 (0.17–0.3) PFHpA, 0.08 (0.05–0.1) PFNA, 0.5 (0.3–0.9) PFDA, 0.5 (0.3–0.8) PFUnDA, 0.4 (0.3–0.6) PFDoA, 0.24 (0.2–0.27) | PCOS | OR (95% CI) in the highest tertile vs. the lowest (the reference) | PFBS: no association PFHxS: no association PFHpA: no association PFNA: no association PFDA: no association PFUnDA: no association PFDoA: (+) 3.0 (1.2–7.7) | Age, BMI, household income, education, employment, age at menarche, menstrual volume |

Abbreviations: AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone; A4, androstenedione; BMI, body mass index; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; EtFOSAA, 2-(N-ethylperlfuorooctane sulfonamide) acetic acid; E2, estradiol; FAI, free androgen index, was calculated as 100 total T/SHBG; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GM, geometric mean; IQR, interquartile range; MeFOSAA, 2-(N-Methylperfluorooctane sulfonamido) acetic acid; NHANES, National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey; NM, not measured; OR, odds ratio; P, progesterone; PCOS, polycystic ovarian syndrome; PFBS, perfluorobutane sulfonic acid; PFDA, perfluorodecanoic acid; PFDoA, perfluorododecanoic acid; PFHpA, perfluoroheptanoic acid; PFHxS, perfluorohexane sulfonic acid; PFNA, perfluorononanoic acid; PFOSA, perfluorooctane sulfonamide; PFUnDA, perfluoroundecanoic acid; POI, premature ovarian insufficiency; PRL, prolactin; p60 and 90, 60th and 90th percentiles; SHBG, sex hormone-binding globulin; T, testosterone; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

total T/SHBG; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GM, geometric mean; IQR, interquartile range; MeFOSAA, 2-(N-Methylperfluorooctane sulfonamido) acetic acid; NHANES, National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey; NM, not measured; OR, odds ratio; P, progesterone; PCOS, polycystic ovarian syndrome; PFBS, perfluorobutane sulfonic acid; PFDA, perfluorodecanoic acid; PFDoA, perfluorododecanoic acid; PFHpA, perfluoroheptanoic acid; PFHxS, perfluorohexane sulfonic acid; PFNA, perfluorononanoic acid; PFOSA, perfluorooctane sulfonamide; PFUnDA, perfluoroundecanoic acid; POI, premature ovarian insufficiency; PRL, prolactin; p60 and 90, 60th and 90th percentiles; SHBG, sex hormone-binding globulin; T, testosterone; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Sex hormones

Exposure to PFAS has been shown to disrupt ovarian steroidogenesis and steroidogenic-controlled processes. Although the literature on other PFAS homologues is scant, epidemiologic evidence suggests that exposure to PFOS is associated with steroidogenic defects. Specifically in the C8 Health Project, PFOS exposure had a significant and negative relationship with serum E2 levels among women aged 42–65 years without a history of hormone contraceptive use (Knox et al., 2011). The parent Energy Balance and Breast Cancer Aspects (EBBA-I) study sampled serum from healthy, naturally cycling women aged 25–35 years and found that, among nulliparous women but not parous women, PFOS exposure was negatively associated with serum E2 and progesterone (P) levels (Barrett et al., 2015). Similarly, Zhang et al. suggested that PFOS exposure may lead to decreased serum E2 and prolactin (PRL) levels and increased FSH levels among premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) patients (Zhang et al., 2018). McCoy et al. also found a negative correlation between PFOS concentrations and E2 levels among women undergoing in vitro fertilization (McCoy et al., 2017). Moreover, Heffernan et al. observed a significant and negative association between PFOS exposure and free androgen index (FAI) among healthy women without PCOS (Heffernan et al., 2018).

In contrast, no associations with hormone levels have been reported for PFOA exposure (Knox et al., 2011; Barrett et al., 2015; McCoy et al., 2017; Heffernan et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). PFOS and PFOA were also not related to serum T levels among women 12–80 years of age from the NHANES 2011–2012 (Lewis et al., 2015). In utero exposure to PFOA and PFOS had no impact on serum levels of total T, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), FAI, DHEA, FSH, LH, E2 or anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) in female adult offspring (Kristensen et al., 2013).

Other PFAS homologues may also have the potential to disturb homeostasis of the endocrine system, although the evidence remains inconclusive. Heffernan et al. found a positive association between PFNA exposure and A4 in both PCOS cases and controls, and a positive association between PFHxS exposure and total T in healthy women (Heffernan et al., 2018). Zhang et al. indicated that PFHxS exposure may increase FSH levels and decrease E2 levels in POI patients (Zhang et al., 2018). No significant associations were observed in cross-sectional studies conducted among naturally cycling women in the EBBA-I study (Barrett et al., 2015), general women in NHANES (Lewis et al., 2015) or women receiving in vitro fertilisation (IVF) (McCoy et al., 2017).

Compared to adults, adolescents may be more susceptible to PFAS toxicity. Serum concentrations of PFOA, PFUnDA and PFOS were inversely associated with serum levels of SHBG, FSH and T, respectively, in adolescents aged 12–17 years but not in young adults (Tsai et al., 2015). Similarly, girls aged 6–9 years who enrolled in the C8 Health Project also had lower serum T levels with higher exposure to PFOS (Lopez-Espinosa et al., 2016). Although no association was observed for PFOA and PFOS exposures with E2 or T in Chinese adolescent girls, serum T levels decreased by 1.2% (95% CI: −2.2%, −0.1%) with an 1-ng/mL increase in serum PFDoA concentrations (Zhou et al., 2016).

Onset age of menarche

Delayed menarche is a common condition defined as the absence of physical signs of puberty by an age  2–2.5 standard deviations above the population mean age of menarche (typically 13 years in girls) (Palmert and Dunkel, 2012). Emerging evidence suggests that later menarche may be linked to negative physiological outcomes and cardiovascular disease in adulthood (Zhu and Chan, 2017). Previous studies examining the associations between exposure to PFAS and timing of menarche have yielded inconsistent results with some of the studies finding no association (Christensen et al., 2011; Lopez-Espinosa et al., 2011; Kristensen et al., 2013). The latter study, a cross-sectional study of 2931 girls 8–18 years of age from the C8 Health Project reported that PFOA and PFOS serum concentrations were associated with later age at menarche, specifically 130 and 138 days of delay when comparing the highest quartile of concentrations versus the lowest quartile, respectively (Lopez-Espinosa et al., 2011).

2–2.5 standard deviations above the population mean age of menarche (typically 13 years in girls) (Palmert and Dunkel, 2012). Emerging evidence suggests that later menarche may be linked to negative physiological outcomes and cardiovascular disease in adulthood (Zhu and Chan, 2017). Previous studies examining the associations between exposure to PFAS and timing of menarche have yielded inconsistent results with some of the studies finding no association (Christensen et al., 2011; Lopez-Espinosa et al., 2011; Kristensen et al., 2013). The latter study, a cross-sectional study of 2931 girls 8–18 years of age from the C8 Health Project reported that PFOA and PFOS serum concentrations were associated with later age at menarche, specifically 130 and 138 days of delay when comparing the highest quartile of concentrations versus the lowest quartile, respectively (Lopez-Espinosa et al., 2011).

In addition, concern exists regarding in utero exposure to PFAS due to high vulnerability in this early-life stage. A Danish birth cohort established in 1988–1989 followed up 267 female offspring when they were ~20 years of age in 2008–2009. The study found that women with in utero exposure to higher concentrations of PFOA reached menarche 5.3 (95% CI: 1.3, 9.3) months later compared with the reference group of lower PFOA concentrations, while no associations were observed for PFOS (Kristensen et al., 2013). In contrast, a study of 218 girls reporting early menarche (before age 11.5 years) and 230 controls (at or after age 11.5 years) born between 1991 and 1992 in the UK showed no association of earlier age at menarche with exposure to PFOSA, EtFOSAA, MeFOSAA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFOA or PFNA (Christensen et al., 2011).

Menstrual cycle characteristics

Disturbances of menstrual cycle manifest in a wide range of presentations. The key characteristics include menstrual cycle regularity, cycle length and the amount of flow, but each of these may exhibit considerable variability. Epidemiologic data on the possible effects of PFAS on menstrual cycle regularity originate primarily from cross-sectional studies (Lyngsø et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2017). Lyngsø et al. reported a statistically significant association between PFOA exposure and longer cycles (cycle length  32 days) with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.8 (95% CI: 1.0–3.3) when comparing the highest tertile of exposure with the lowest, in 1623 fertile women enrolled in the Inuit-endocrine (INUENDO) cohort from three countries (Greenland, Poland and Ukraine), whereas no significant results were detected for PFOS (Lyngsø et al., 2014). Moreover, a cross-sectional analysis of 950 Chinese women revealed that increased exposures to PFOA, PFOS, PFNA and PFHxS were associated with higher odds of irregular and longer menstrual cycle but lower odds of menorrhagia (Zhou et al., 2017). Interestingly, women with higher concentrations of PFOA, PFNA and PFHxS were more likely to experience hypomenorrhea (Zhou et al., 2017).

32 days) with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.8 (95% CI: 1.0–3.3) when comparing the highest tertile of exposure with the lowest, in 1623 fertile women enrolled in the Inuit-endocrine (INUENDO) cohort from three countries (Greenland, Poland and Ukraine), whereas no significant results were detected for PFOS (Lyngsø et al., 2014). Moreover, a cross-sectional analysis of 950 Chinese women revealed that increased exposures to PFOA, PFOS, PFNA and PFHxS were associated with higher odds of irregular and longer menstrual cycle but lower odds of menorrhagia (Zhou et al., 2017). Interestingly, women with higher concentrations of PFOA, PFNA and PFHxS were more likely to experience hypomenorrhea (Zhou et al., 2017).

The relationship of PFOA and PFOS with menstrual irregularity was detected in a subset of 1240 pregnant women randomly selected from the Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC); women had higher exposure to PFOA and PFOS tended to report having irregular periods (Fei et al., 2009). Lum et al. used data from 501 couples from Michigan and Texas, who upon their discontinuing contraception for purposes of becoming pregnant enrolled in a prospective cohort, the Longitudinal Investigation of Fertility and the Environment (LIFE) Study (Lum et al., 2017). Menstrual cycles were 3% longer among women in the second versus the lowest tertile of PFDA serum concentrations, but 2% shorter for women in the highest versus the lowest tertile of PFOA concentrations, while no associations were observed with PFOS (Lum et al., 2017). When examining the effects of prenatal exposure, a recent prospective study found no associations between maternal exposure to PFOA and PFOS and menstrual cycle length or number of ovarian follicles in their offspring (Kristensen et al., 2013).

Ovarian aging

POI represents a gynaecological disorder characterised by the absence of normal ovarian function due to depletion of the follicle pool before age 40 years with the presence of oligo/amenorrhea for at least 4 months in combination with elevated FSH levels. It should be noted that POI is the transitional stage from normal ovarian function to complete loss of ovarian function. A case–control study of 240 Chinese women found that high exposures to PFOA, PFOS and PFHxS were associated with increased risks of POI; however, no associations were observed for PFNA, PFDA, PFUnDA, PFDoA, PFHpA and PFBS (Zhang et al., 2018).

Beyond the problem of infertility in POI patients, diminished ovarian reserve and extended steroid hormone deficiency during ovarian aging have far-reaching health implications. Earlier age at natural menopause has been associated with an increased risk of overall mortality (Jacobsen et al., 2003; Mondul et al., 2005; Ossewaarde et al., 2005), cardiovascular disease (Hu et al., 1999; Atsma et al., 2006) and cardiovascular death (van der Schouw et al., 1996; de Kleijn et al., 2002; Mondul et al., 2005), low bone mineral density (Parazzini et al., 1996) and osteoporosis (Kritz-Silverstein and Barrett-Connor, 1993) and other chronic conditions (Shuster et al., 2010). Quality of life may be significantly decreased while risks of sexual dysfunction and neurological disease may be increased later in life (McEwen and Alves, 1999; Van Der Stege et al., 2008; Rocca et al., 2009).

A study of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) participants found that higher PFAS concentrations were associated with earlier menopause: the hazard ratio (HR) of natural menopause was 1.42 (95% CI: 1.08, 1.87) comparing PFHxS serum concentrations in tertile 2 versus tertile 1, and 1.70 (95% CI: 1.36, 2.12) in tertile 3 versus tertile 1; positive dose–response relationships were also detected for PFOA, PFOS, PFNA and PFHxS with hysterectomy (Taylor et al., 2014). Additionally, a cross-sectional study of the C8 Health Project participants found that the odds of having already experienced natural menopause increased with increasing exposure quintiles of PFOA and PFOS, particularly in women aged 42–65 years (Knox et al., 2011).