Highlights

-

•

Possible risk of severe COVID-19 in children with WS (hormonal therapy, young age, comorbidities).

-

•

Risk of worsening epileptic spasms with COVID-19: not known.

-

•

First-choice for WS based on risk stratification, availability of drugs, clinician’s preference and judgement.

-

•

Sustenance of optimal care and reduction in treatment lag by means of tele-epileptology and maintenance of drug supply chain.

-

•

Need for developing a global consortium to assess impact and interaction of COVID-19 with WS.

Keywords: Infantile spasms, Epileptic spasms, Infants, COVID-19

Abstract

In the wake of the pandemic COVID-19 and nationwide lockdowns gripping many countries globally, the national healthcare systems are either overwhelmed or preparing to combat this pandemic. Despite all the containment measures in place, experts opine that this novel coronavirus is here to stay as a pandemic or an endemic. Hence, it is apt to be prepared for the confrontation and its aftermath. From protecting the vulnerable individuals to providing quality care for all health conditions and maintaining essential drug supplies, it is going to be a grueling voyage. Preparedness to sustain optimal care for each health condition is a must. With a higher risk for severe COVID-19 disease in infants, need of high-dose hormonal therapy with a concern of consequent severe disease, presence of comorbidities, and a need for frequent investigations and follow-up; children with West syndrome constitute a distinctive group with special concerns. In this viewpoint, we discuss the important issues and concerns related to the management of West syndrome during COVID-19 pandemic in the South Asian context and provide potential solutions to these concerns based on the current evidence, adeptness, and consensus. Some plausible solutions include the continuation of containment and mitigation measures for COVID-19, therapeutic decision- making for West syndrome based on risk stratification, and tele-epileptology.

1. Introduction

The Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), is a global health concern. In a systematic review, children accounted for 1–5 % of diagnosed cases (Ludvigsson, 2020). Although most children and infants remain asymptomatic or mildly affected, the prevalence of the severe and critical disease in infancy is to the tune of 10 % (Ludvigsson, 2020). Besides COVID-19, the nationwide lockdowns and diversion of resources have significantly impacted the care of patients with other medical conditions. In developing countries with a relatively low doctor-patient ratio, this might lead to a delay in seeking medical attention due to constraints of funds, halted transport facilities, fear of SARS-CoV-2 infection, poor awareness, etc. Other nuances such as unavailability of imported drugs, a standstill of regular clinic activities and rehabilitation services, etc. may be additive.

Preparedness to sustain optimal care for each health condition is a must. In this context, West syndrome (WS) being the commonest epileptic encephalopathy constitutes a distinctive condition considering the higher risk of severe COVID-19 disease in infants, peculiar management options [high-dose hormonal therapy (oral steroids and adrenocorticotrophic hormone; ACTH) and vigabatrin], need for frequent follow-up, and dependence of therapeutic response on treatment lag (O’Callaghan et al., 2011). COVID-19 pandemic has led to change in management practices for WS all over the world (Wirrell et al., 2020). Child Neurology Society (CNS) and Pediatric Epilepsy Research Consortium in the United States have recently published recommendations for infantile spasms/WS to steer through this pandemic (Grinspan et al., 2020). However, there would be applicability concerns for South Asia and developing countries due to peculiar management practices and challenges for WS. A preponderance of structural etiology, long treatment lag, difficult access to EEG, availability and licensing issues with the first-line drugs (ACTH and vigabatrin), and underdeveloped telehealth services make this region eccentric (Madaan et al., 2020; Vaddi et al., 2018). Although the fundamental management principles are analogous, the global applicability of CNS recommendations is limited. While our knowledge is still evolving, preparedness is essential by pediatric neurologists. Hence, this paper focuses on providing answers to potentially important issues in the management of WS during COVID-19 pandemic in South Asian context based on current evidence, expertise, experience, and consensus.

2. Methods

South Asian West Syndrome Research Group (SAWSRG) was formed in early 2019, while studying the management practices for WS in South Asia (Madaan et al., 2020). The members of the SAWSRG identified the key issues concerning COVID-19 with WS. A detailed literature search was performed using the electronic databases PubMed/Medline, Google Scholar, Web of Science, Website content of World health Organization and ILAE from December 2019 to May 15, 2020, with “COVID-19″ OR “2019-nCovid” AND “infantile spasms” OR “West syndrome” as search terms. Subsequently, an interactive online meeting and multiple correspondences were held among the group members to formulate the viewpoint, and a consensus was obtained on issues with uncertainty. Literature review was subsequently updated till July 19, 2020.

3. Key issues

3.1. Risk of COVID-19 in children with WS

Children with WS often have associated comorbidities, e.g. development delay, spasticity, etc. secondary to underlying structural etiology. Recurrent hospitalization due to respiratory infection, aspiration, gastroesophageal reflux disease, etc. is also common. Harini et al. reported a higher risk of mortality (18 %) in WS and identified the persistence of epileptic spasms and respiratory comorbidity as poor prognostic markers (Harini et al., 2020). Frequent healthcare visits for ACTH administration, monitoring of adverse effects, etc. are additional risk factors for acquiring SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, children having WS are likely at a higher risk of becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2.

3.2. Risk of worsening epileptic spasms with COVID-19

Acute symptomatic seizures or worsening epilepsy control in children with epilepsy is uncommon and infrequently reported with COVID-19 (Lu et al., 2020; Aledo-Serrano et al., 2020). Besides, acute febrile illnesses and pyretotherapy (artificial fever therapy) have been associated with spontaneous remission of epileptic spasms and resolution of hypsarrhythmia in children with WS (Garcia de Alba et al., 1984; Sugiura et al., 2007). However, there is no evidence to support or refute the same with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

3.3. First choice drug for WS, in the absence of SARS-CoV-2 infection

Hormonal therapy is the standard first-line therapy for WS, excluding tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). Although it has been associated with unusual infections such as Pneumocystis jiroveci, etc., there is no strong evidence for its impact on the severity of COVID-19 (Minotti et al., 2020). Risk assessment, based on community transmission of SARS-CoV-2, may be a useful strategy for the management of WS during the pandemic. Hormonal therapy may be safely considered in the absence of community transmission. In concurrence with CNS guidelines, high-dose oral steroids (4−8 mg/kg/day; initiated in outpatient setting) may be preferred over ACTH considering the ease of administration and availability (Grinspan et al., 2020). In regions with community transmission, treatment with hormonal therapy may be individualized based on the physician’s judgement of the risks involved, and vigabatrin may be considered before hormonal therapy. The non-availability of vigabatrin due to licensing issues, poor supply, etc. might be an issue in some of the countries. Valproate, high-dose zonisamide, topiramate, etc. may also be considered if the first-line treatment options are not feasible or contraindicated.

3.4. Management in children with WS and suspected COVID-19

The children, who develop fever, cough, and other respiratory symptoms during the treatment of WS, should be tested for SARS-CoV-2 depending on contact history, endemicity of infection, and regional guidelines. Children with confirmed COVID-19 should be hospitalized and isolated while the continuation of high-dose hormonal therapy may be concerning, and there are two possible options. First, the child may be continued on high-dose hormonal therapy as this remains the most efficacious treatment option for cessation of epileptic spasms. Furthermore, there are reports of the mild clinical course of COVID-19 in children already on immunosuppressants (Marlais et al., 2020). However, the risks of increased viral replication and rebound cannot be negated (Russell et al., 2020). Another option is to switch high-dose hormonal therapy to stress dose steroids dose during the active infection. The answer to the best choice remains unknown at this point in time and would await further evidence. The decision may be individualized by treating clinicians based on the clinical severity and response of epileptic spasms with the high-dose hormonal therapy. Children with COVID-19, who are not on/ not respond to hormonal therapy, may be treated with other options, e.g. vigabatrin, zonisamide, etc.

3.5. Drug interactions with anti-COVID-19 drugs

The important drugs which may be useful in COVID-19 include antiviral drugs such as lopinavir, ritonavir (LPV/r), atazanavir (ATV), remdesivir (RDV), favipiravir (FAVI), etc. (Chiotos et al., 2020). These drugs might interact with antiseizure medications for epileptic spasms. It is safe to administer oral prednisolone with RDV and FAVI (Liverpool COVID-19 Interactions [Internet], 2020 July). However, LPV/r and ATV tend to increase corticosteroid levels and require dose adjustment since LPV/r and ATV are inhibitors of CYP3A4 (Antiepileptic-drugs-interactions_in_COVID-19.pdf [Internet], 2020 May). Vigabatrin doesn’t have any significant interaction with any of these drugs (Liverpool COVID-19 Interactions [Internet], 2020 July; Antiepileptic-drugs-interactions_in_COVID-19.pdf [Internet], 2020 May).

3.6. Targeting treatment lag with tele-epileptology

Tele-epileptology should be considered as an armament against COVID-19. It decreases face-to-face healthcare visits and contact. Teleconsultations may also help steer through the problem of treatment lag which will probably be compounded by lockdowns and fear of COVID-19 among the patient families. The telemedicine applications using video mode of communication including telemedicine facilities, video-call on chat platform, Skype, etc. are preferred options (Telemedicine Practice Guidelines, 2020 July). There is a need for end-to-end encryption and secure telehealth platforms for teleconsultations. The telehealth facilities are not easily available at many places in South Asia; however, smartphones are of universal access. Therefore, smartphone mobile apps, e.g. WhatsApp, which are secured with end-to-end encryption, may be used for video-call, interaction, sharing of patient videos, and prescription. Home-videos of spasms must be analyzed in the context of history (history of hypopigmented patches), age of onset, clinical semiology including clustering, and occurrence with awakening. The development and validation of an objective clinical score based on clinical videos may also be helpful in this regard.

Although an initial outpatient EEG confirmation of hypsarrhythmia and subsequent 2-week follow-up EEG to demonstrate therapeutic response, as recommended by the CNS, are desirable, the decision may be individualized based on the feasibility and access of pediatric EEG services. In concurrence with the CNS recommendations, outpatient EEG should be preferred including at least one sleep-wake cycle (Grinspan et al., 2020). Efforts should be made to ensure wider availability of pediatric EEG facilities in South Asia.

3.7. Concerns of a shortage of medications

There is a concern about the possibility of medicine shortage, especially ACTH and vigabatrin, due to the interruption of the drug supply chain during the pandemic and lockdown. Considering the limited therapeutic choices for WS, this would negatively impact the outcome. Hence, it is important to have the preparedness to prevent such an occurrence. Good coordination between government health care agencies, pharmaceutical companies, and medical suppliers is recommended.

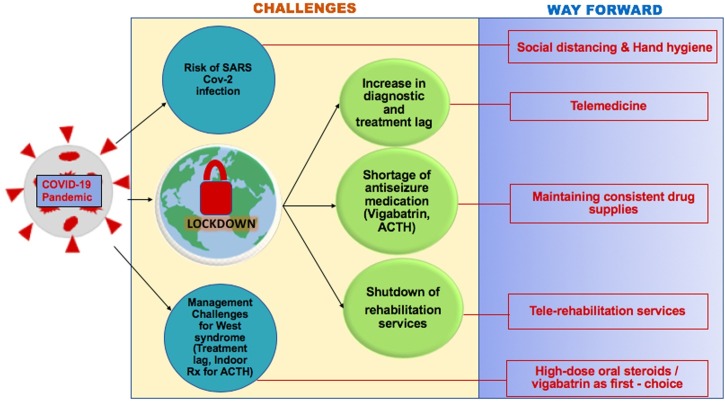

4. Conclusions

In these challenging times with concerns of mounting pandemic and pre-emptive lockdowns for containment, it is really important to have preparedness for the management of children with WS. These children may be at a higher risk of severe disease if they suffer from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Minimization of diagnostic and treatment lag should be the priority. Hormonal therapy should be carefully used in regions with community transmission. Telemedicine facilities should be developed and used to optimize the care of these children. Government and healthcare policymakers should take the necessary steps to prevent a shortage of medications. These viewpoints (Fig. 1 , Box 1 ) may prove helpful in permeating this crisis by providing important insights. There is a need to develop a global consortium to assess the impact and interaction of COVID-19 with WS.

Fig. 1.

The panel shows the interplay of various effects of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns on children with West syndrome and plausible solutions.

Box 1. Key issues and solutions for the management of West syndrome during COVID-19 pandemic.

-

1Probable risk of COVID-19 in children with WS: due to

-

aFrequent hospital visits

-

bComorbidities: Recurrent respiratory infections, gastroesophageal reflux

-

a

-

2

Risk of worsening epileptic spasms with COVID-19: unknown

-

3First-choice drug selection for WS, in the absence of SARS-CoV-2 infection: based on

-

aRisk stratification (based on community transmission) for hormonal therapy

-

bAvailability of drugs

-

cClinician’s preference prior to the pandemic

-

a

-

4Management in children with WS and suspected COVID-19

-

aTesting, isolation, and management of COVID-19

-

bModification of drugs for WS based on

-

iClinician’s judgement of the severity of COVID-19 (for steroids)

-

iiClinical response (resolution of spasms and hypsarrhythmia)

-

iiiDrug interactions between antiseizure medications and anti-COVID-19 drugs

-

i

-

a

-

5Solutions for the sustenance of care and reduction of treatment lag

-

aTele-epileptology

-

bMaintaining a drug supply chain

-

a

Alt-text: Box 1

COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 19; WS, West syndrome; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Authors’ contribution

Jitendra Kumar Sahu contributed by conception and planning of the study, literature review, participated as an expert, preparation of initial draft of manuscript, and its revision for intellectual content.

Priyanka Madaan contributed by planning of the study, literature search, participated as an expert, preparation of initial draft of manuscript, and its revision for intellectual content.

Prem Chand contributed by participating as an expert and by critical review of the manuscript for intellectual content.

Amit Kumar contributed by literature search and by critical review of the manuscript for intellectual content.

Kyaw Linn contributed by participating as an expert and by critical review of the manuscript for intellectual content.

Mimi Lhamu Mynak contributed by participating as an expert and by critical review of the manuscript for intellectual content.

Prakash Poudel contributed by participating as an expert and by critical review of the manuscript for intellectual content.

Jithangi Wanigasinghe contributed by participating as an expert and by critical review of the manuscript for intellectual content.

Ethical publication statement

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Study funding

None.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Dr. Jitendra Kumar Sahu serves as a section editor for Indian Journal of Pediatrics and received extramural research grant from Indian Council of Medical Research for “West syndrome-EAST" trial. However, no disclosure pertaining to the study. Rest of the authors have no conflict of interest to disclose with regard to this article.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- Aledo-Serrano A., Mingorance A., Jiménez-Huete A., Toledano R., García-Morales I., Anciones C. Genetic epilepsies and COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from the caregiver perspective. Epilepsia. 2020;61:1312–1314. doi: 10.1111/epi.16537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antiepileptic-drugs-interactions_in_COVID-19.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: https://www.ilae.org/files/dmfile/Antiepileptic-drugs-interactions_in_COVID-19.pdf.

- Chiotos K., Hayes M., Kimberlin D.W., Jones S.B., James S.H., Pinninti S.G. Multicenter initial guidance on use of antivirals for children with COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2020 doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa045. ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia de Alba G.O., Garćia A.R., Crespo F.V. Pyretotherapy as treatment in West’s syndrome. Clin EEG Electroencephalogr. 1984;15:140–144. doi: 10.1177/155005948401500304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinspan Z.M., Mytinger J.R., Baumer F.M., Ciliberto M.A., Cohen B.H., Dlugos D.J. Management of infantile spasms during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Child Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0883073820933739. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harini C., Nagarajan E., Bergin A.M., Pearl P., Loddenkemper T., Takeoka M. Mortality in infantile spasms: a hospital-based study. Epilepsia. 2020;61:702–713. doi: 10.1111/epi.16468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liverpool COVID-19 Interactions [Internet]. [cited 2020 July 17]. Available from: https://www.covid19-druginteractions.org/ prescribing-resources.

- Lu L., Xiong W., Liu D., Liu J., Yang D., Li N. New onset acute symptomatic seizure and risk factors in coronavirus disease 2019: a retrospective multicenter study. Epilepsia. 2020;61:e49–e53. doi: 10.1111/epi.16524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludvigsson J.F. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109:1088–1095. doi: 10.1111/apa.15270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madaan P., Chand P., Linn K., Wanigasinghe J., Mynak M.L., Poudel P. Management practices for West syndrome in South Asia: a survey study and meta-analysis. Epilepsia Open. 2020 doi: 10.1002/epi4.12419. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlais M., Wlodkowski T., Vivarelli M., Pape L., Tönshoff B., Schaefer F. The severity of COVID-19 in children on immunosuppressive medication. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4:e17–e18. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30145-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minotti C., Tirelli F., Barbieri E., Giaquinto C., Donà D. How is immunosuppressive status affecting children and adults in SARS-CoV-2 infection? A systematic review. J. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.026. ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan F.J.K., Lux A.L., Darke K., Edwards S.W., Hancock E., Johnson A.L. The effect of lead time to treatment and of age of onset on developmental outcome at 4 years in infantile spasms: evidence from the United Kingdom Infantile Spasms Study. Epilepsia. 2011;52:1359–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell B., Moss C., Rigg A., Van Hemelrijck M. COVID-19 and treatment with NSAIDs and corticosteroids: should we be limiting their use in the clinical setting? Ecancermedicalscience. 2020;14:1023. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2020.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura C., Maegaki Y., Kure H., Inoue T., Ohno K. Spontaneous remission of infantile spasms and hypsarrhythmia following acute infection with high-grade fever. Epilepsy Res. 2007;77(2–3):102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telemedicine Practice Guidelines Enabling Registered Medical Practitioners to Provide Healthcare Using Telemedicine [Internet]. [cited 2020 July 19]. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/Telemedicine.pdf/.

- Vaddi V.K., Sahu J.K., Dhawan S.R., Suthar R., Sankhyan N. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice (KAP) Study of Pediatricians on Infantile Spasms. Indian J. Pediatr. 2018;85:836–840. doi: 10.1007/s12098-018-2630-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirrell E.C., Grinspan Z.M., Knupp K.G., Jiang Y., Hammeed B., Mytinger J.R. Care delivery for children with epilepsy during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international survey of clinicians. J. Child Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0883073820940189. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]