Abstract

Methamphetamine (METH) is a highly addictive psychostimulant and one of the most widely abused drugs worldwide. The continuous use of METH eventually leads to drug addiction and causes serious health complications, including attention deficit, memory loss and cognitive decline. These neurological complications are strongly associated with METH-induced neurotoxicity and neuroinflammation, which leads to neuronal cell death. The current review investigates the molecular mechanisms underlying METH-mediated neuronal damages. Our analysis demonstrates that the process of neuronal impairment by METH is closely related to oxidative stress, transcription factor activation, DNA damage, excitatory toxicity and various apoptosis pathways. Thus, we reach the conclusion here that METH-induced neuronal damages are attributed to the neurotoxic and neuroinflammatory effect of the drug. This review provides an insight into the mechanisms of METH addiction and contributes to the discovery of therapeutic targets on neurological impairment by METH abuse.

Keywords: Methamphetamine, Neurotoxicity, Neuroinflammation, Excitotoxicity, Apoptosis

INTRODUCTION

Methamphetamine (METH) is a well-known psychostimulant that can cause neurotoxicity and is one of the most widely abused drugs worldwide (Elkashef et al., 2008). The continuous use of METH promotes neurodegeneration and cognitive decline (Rusyniak, 2011; Dean et al., 2013). In addition, chronic METH abuse is reported to cause selective patterns of brain deterioration leading to memory impairment (Meredith et al., 2005).

The abuse of METH is closely related to the release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine (DA) (Saha et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2016). During the development of drug addiction, drug-seeking behavior proceeds from seeking the reward effect of drugs to being triggered by drug-associated cues (Robbins et al., 2008). Therefore, greater decrease in dorsal striatal DA in METH abusers might promote habitual drug use (Wang et al., 2012). METH increases DA neurotransmission via regulation of dopamine transporters (DATs) activity (Lin et al., 2016; Sambo et al., 2017). A recent study shows that a decrease of DATs in METH abusers increases the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease (Chen et al., 2013; Granado et al., 2013). Parkinson’s disease (PD) is caused by degeneration of DA neurons in the midbrain. Biochemical and neuroimaging studies of human METH users revealed that the levels of DA and DATs were decreased, and microglia activation in striatum and other areas of the brain was also detected, which appears to be similar to that observed in PD patients (Granado et al., 2013). METH is also known to cause neuronal inflammation, which eventually leads to neural degeneration (Cadet and Krasnova, 2009). Directly or indirectly, METH-induced neuroinflammation makes the brain more susceptible to neuropathology (Cadet and Krasnova, 2009).

Neuronal cells are highly susceptible to pro-inflammatory cytokine-induced damage, and exposure to pro-inflammatory cytokines has been shown to cause neuronal cell apoptosis (Castino et al., 2007). Moreover, neuroinflammation can increase the oxidative stress by excessive release of harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS), which further promote neuronal damage and subsequent inflammation resulting in a feed-forward loop of neurodegeneration (Fischer and Maier, 2015). There are a number of excellent reviews outlining the health and societal concerns stemming from METH abuse and overdose, yet there remains a paucity of information related to neuroinflammation and neurotoxicity in METH abusers (Matsumoto et al., 2014). Therefore, to provide a guide for future research, we want to review neuronal cell apoptosis through neurotoxic and neuroinflammatory mechanisms caused by METH.

METH-INDUCED NEUROTOXICITY

Dopaminergic pathway

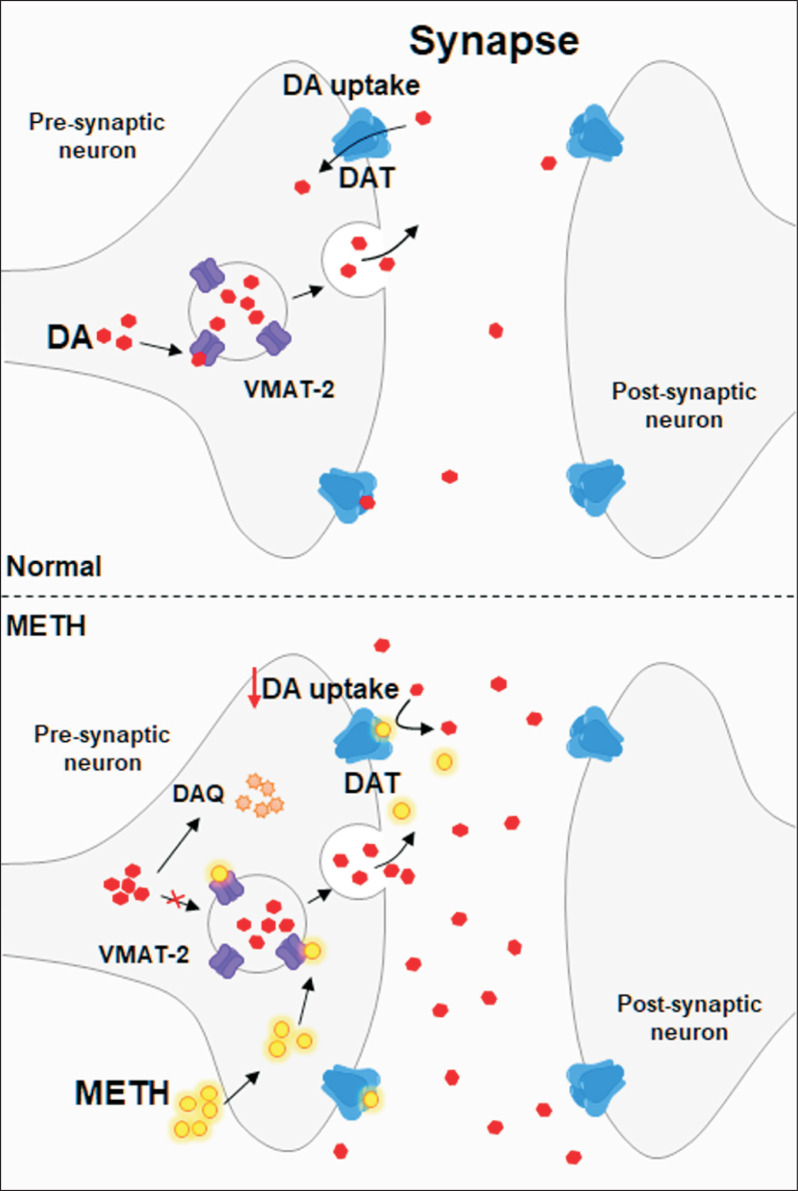

Methamphetamine is a psychostimulant that primarily induces the release of dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine (Rothman et al., 2001). These neurotransmitters are involved in neuronal cell inflammation and necrosis in the mesolimbic region of the brain (Panenka et al., 2013). The process of intoxication of METH is closely related to the induction of DA release. Chronic METH intake regulates dopamine release by acting primarily on vesicle monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT-2) and plasma membrane DATs, two major molecules of the dopaminergic neuronal terminal (Fig. 1) (Kahlig and Galli, 2003). DATs are responsible for dopamine reuptake into the presynaptic dopaminergic neurons from the extracellular area, which is extremely important for regulating and maintaining dopamine homeostasis (Fleckenstein et al., 2007). Under normal circumstances, neuronal activation promotes the release of DA into the synapse (Nickell et al., 2014). The DATs removes DA from the synapse, and the VMAT-2 transports cytoplasmic DA into vesicles for storage, release, and protection from oxidation and reactive consequences (Riddle et al., 2006). However, METH causes abnormal trafficking of DATs, which means that METH increases extracellular dopamine levels by inhibiting dopamine reuptake, stimulating dopamine efflux, and internalizing DATs from the plasma membrane (Riddle et al., 2006). Moreover, METH increases the excitability of dopaminergic neurons in a DATs-dependent manner. The DAT is a member of Na+/Cl– dependent co-transporters (Sonders et al., 1997), and bidirectional transport of dopamine through DATs is achieved by the movements of Na+/Cl– ions. METH enhances DATs-mediated inward current and promotes the excitability of dopamine neurons (Chu et al., 2008; Schmitt and Reith, 2010; Saha et al., 2014).

Fig. 1.

METH regulates dopamine release by acting on DAT and VMAT-2. Vesicles containing DA are transferred to the extracellular space (synapse) and DA is released. In normal conditions, DAT mediates the DA reuptake, however, METH causes DA accumulation in the synapse by blocking DA uptake via interaction with DAT. METH also causes synaptic vesicles to leak monoamines into the cytosol and promotes the generation of dopamine-quinone (DAQ), which results in neurotoxicity.

VMAT-2 is an integral membrane protein that transports monoamines from the intracellular cytosol into synaptic vesicles (Fleckenstein et al., 2009). However, METH causes synaptic vesicles to leak monoamines into the cytosol by disrupting the hydrogen pump-mediated proton gradient (Fleckenstein et al., 2007). Moreover, METH binds to VMAT-2 and competitively inhibits the uptake of monoamines leading to high concentrations of monoamines in the cytoplasm (Sulzer et al., 1992, 1993). Moreover, dysfunction of VMAT-2 due to METH interferes with physiological storage of DA, resulting in a significant increase in DA levels in endogenous cells (Lazzeri et al., 2007; German et al., 2012). Thus, high concentrations of DA, which can freely diffuse in cells, can easily cause large amounts of oxidative damage, which is associated with the neurotoxic effects of large amounts of METH (Hogan et al., 2000; Volkow et al., 2001; Eyerman and Yamamoto, 2007).

METH-induced neurotoxicity

Upon METH stimulation, large amounts of DA from cytosol and synaptic clefts are oxidized to quinone or semi-quinone. And, increasing of DA oxidation further leads to significant production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydroxyl radicals (OH–), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and superoxide anions (O2–) (Yang et al., 2018). These ROS can inhibit mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, which in turn results in a depolarized mitochondrial membrane potential and mitochondrial dysfunction (Stokes et al., 1999; Zhu et al., 2006; Dawson and Dawson, 2017). Dysfunction of mitochondrial metabolism has been reported to play a very important role in METH-induced neurotoxicity, because it inhibits the Krebs cycle and electron transport chain (ETC) and potentiates oxidative stress (Ares-Santos et al., 2013). Therefore, defects in mitochondrial respiration can cause neuronal cell death and neurodegenerative diseases.

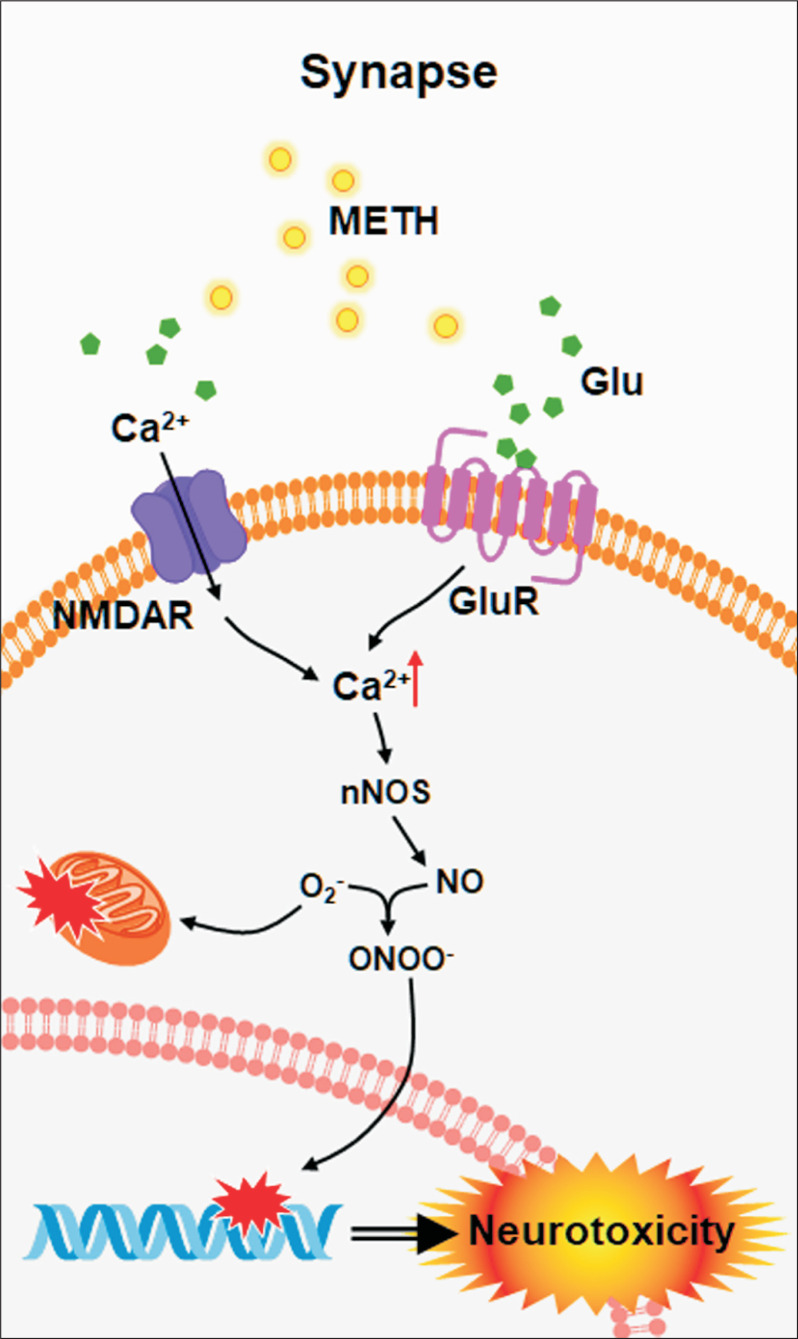

The hypothesis about the involvement of glutamate (Glu) in METH toxicity is supported by the discovery that METH causes Glu release in the brain (Baldwin et al., 1993; Abekawa et al., 1994). Glu is a major excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain and has been reported to play an important role in the excitotoxicity induced by METH (Moratalla et al., 2017). Specifically, large amounts of Glu by METH activate the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) and metabolic glutamate receptor (mGluR) (Ohno et al., 1994; Battaglia et al., 2002; Tseng et al., 2010). Glu accumulation overstimulates various downstream signal transduction pathways associated with Ca2+ influx, which leads to increased intracellular Ca2+ concentrations (Chamorro et al., 2016). The excessive production of Ca2+ in cells activates protein kinases, phosphatase, and nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and promotes NO production (Moratalla et al., 2017). Excessive NO production leads to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, activation of the apoptotic pathway, and eventually causes neurotoxicity by METH (Moratalla et al., 2017). Previous report supported that glutamate-mediated NO formation may also be involved in METH toxicity because knockout mice lacking neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS or iNOS) are protected from METH-induced damage from monoaminergic axons (Itzhak et al., 1998). In addition, in many studies, various nNOS inhibitors are also known to protect against the depletion of monoaminergic axons caused by METH administration (Itzhak et al., 2000; Sanchez et al., 2003). These evidences indicate a glutamate/NO pathway plays a major role in METH-induced neurotoxicity (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

METH induces Glu-mediated neurotoxicity. METH causes Glu accumulation in the synapse, and high concentration of Glu stimulates downstream pathways associated with Ca2+ influx. The excessive Ca2+ mediated neurotoxicity by activation of various enzymes related to DNA damage and ER stress.

METH-induced neuroinflammation

METH is also known to contribute to neuronal inflammation through excessive release of DA and Glu (Kohno et al., 2019). The released DA is oxidized to form toxic quinones, leading to presynaptic membrane damage via oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and the subsequent production of peroxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide (Kohno et al., 2019). The impairment of mitochondrial energy metabolism as well as the release of inflammatory cytokines increases the response to synapses and neuroinflammation (Li et al., 2008; Tocharus et al., 2010; Panenka et al., 2013; Loftis and Janowsky, 2014). It has been reported that these METH-induced neuroinflammation is caused by targeting microglia, the innate immune cells of the central nervous system (Sekine et al., 2008).

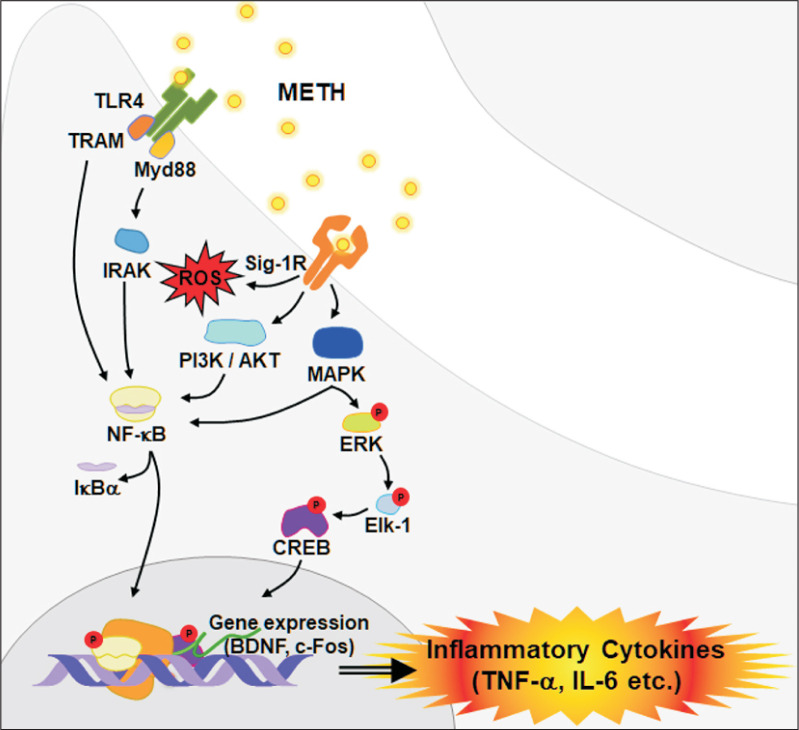

Indeed, METH-mediated activation of microglia is associated with Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), which is involved in immune surveillance of pathogens and exogenous small molecules (Bachtell et al., 2015; Du et al., 2017). TLR4 is a receptor that can activate both the Myd88-dependent and Myd88-independent pathways (Billod et al., 2016). In the Myd88-dependent pathway, Myd88 activates tumor necrosis factor receptor-related factor 6 (TRAF6), interleukin-1 receptor related kinase (IRAK) to induce nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation (Shen et al., 2016). Consequently, the activation of TLR4 due to METH increases inflammatory mediators such as interleukin (IL)-1α, 1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IL-6 (Wan et al., 2017). In contrast, the MyD88-independent pathway leads to the induction of IFN-γ through the activation of TRIF-related adapter molecule (TRAM) and interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) (Brempelis et al., 2017). The MyD88-independent pathway also induces NF-κB activation, but it occurs later than activation through the MyD88-dependent pathway (Liu et al., 2012). NF-κB is a well-known transcription factor involved in neurodegenerative progression, and it is considered to be a key target for prevention and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases (Majdi et al., 2019).

Sig-1R is an ER chaperone protein that is widely expressed throughout the brain and has a high affinity for METH (Hayashi et al., 2010). Sig-1R is closely related to toxicity and inflammation caused by METH (Hedges et al., 2018) via regulation of various mechanisms such as calcium homeostasis, glutamate activity, ROS formation, ER and mitochondrial function (Nguyen et al., 2015; Ruscher and Wieloch, 2015). Another study reported that activation of microglia due to METH stimulation can be mediated by Sig-1Rs via ROS generation and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathways (Chao et al., 2017). The MAPK signaling pathway is also closely related to the NF-κB signaling pathway (Zanassi et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2009), with both playing key roles in the induction of inflammatory cytokines by METH (Liu et al., 2012).

ERK is a representative kinase that plays an important role in regulating neuronal and behavioral processes mediated by DA and Glu (Shiflett and Balleine, 2011). ERK is activated by neurotrophin or growth factor (Sun et al., 2016), and phosphorylated ERK is translocated to the nucleus and subsequently phosphorylates Elk-1 (Besnard et al., 2011). Activated Elk-1 promotes immediate early gene (IEG) transcription associated with neural adaptation (Davis et al., 2000). Another study demonstrated that the ERK signaling pathway is linked to the regulation of dopamine D1 receptor involved in rewarding effects induced by METH (Mizoguchi et al., 2004). It has also been reported that METH can increase the activation of ERK phosphorylation in certain brain regions (Son et al., 2015). Once activated, ERK causes cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation and enhances the expression of c-Fos (Valjent et al., 2005). CREB is a transcription factor that is phosphorylated by different kinases, including protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC) (Johannessen and Moens, 2007; Shin et al., 2012). CREB phosphorylation sequentially promotes the recruitment of co-activators such as CREB-binding protein (CBP)/p300 to the basal transcriptional machinery, which is followed by increased expression of target genes such as Arc, c-Fos, Egr1, Fos-b, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Barco et al. 2005; Beaumont et al., 2012). A previous study supported that METH self-administration was accompanied by increased recruitment of phosphorylated CREB on the promoter of c-Fos (Krasnova et al., 2016). These are important processes that promote neurological inflammation by releasing various pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, monocyte chemical attractant protein 1 (MCP-1), and cell adhesion molecule (ICAM-1) (Fig. 3) (Snider et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2018).

Fig. 3.

METH contributes to neuroinflammation. METH activates TLR4 and Sig-1R, triggering downstream signal pathways including NF-κB, MAPK and PI3K/Akt. Activation of CREB, c-Fos and BDNF promotes nerve inflammation through expression of various inflammatory cytokines.

APOPTOSIS DUE TO METH-INDUCED NEUROTOXICITY AND INFLAMMATION

Mitochondria-mediated death pathway

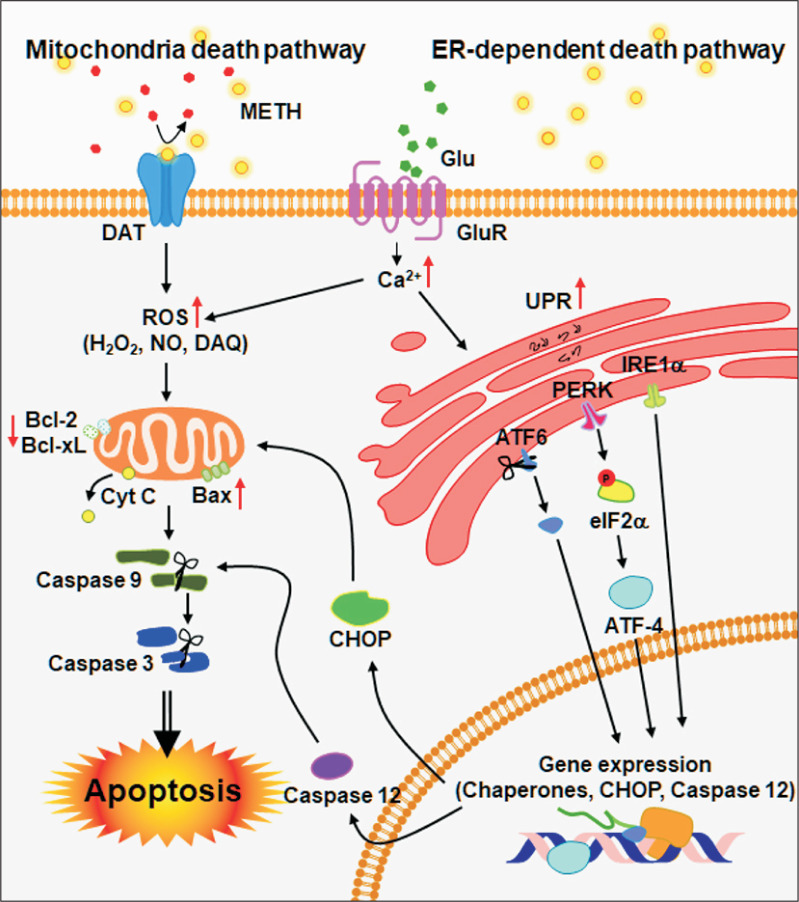

As mentioned above, cytotoxicity and inflammation caused by METH leads to neuronal cell death. Besides ROS and NO, B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) family proteins are also involved in METH-induced neurotoxicity and inflammation (Jayanthi et al., 2001). Previous studies have reported that METH exposure increases the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bax, Bad, Bid and decreases the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL (Jayanthi et al., 2001, 2004; Beauvais et al., 2011). The increase of pro-apoptotic proteins by METH is due to the release of mitochondrial intermembrane space (IMS) proteins, including apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) and cytochrome c (Galluzzi et al., 2009). AIF and second mitochondria-derived activator of caspases/direct IAP-binding protein with low isoelectric point, PI (SMAC/DIABLO), which are released from mitochondria, activate the caspase-9 and -3 to induce neuronal cell death (Cadet et al., 2005). The release of cytochrome c is another key step in the caspase-dependent mitochondrial apoptotic pathway (Shin et al., 2018). Cytochrome c forms apoptosome, which is composed of Apaf-1, dATP and procaspase-9, and then induces sequential activation of the executioner caspases-3, -6 and -7 (Shin et al., 2018). Many studies regarding METH-mediated apoptosis show increased cytochrome c release from mitochondria and subsequent caspase activation after METH exposure in vitro (Nam et al., 2015; Park et al., 2017) and in vivo (Deng et al., 2002; Jayanthi et al., 2004; Beauvais et al., 2011; Dang et al., 2016). Another study suggested that activation of caspase-3 and PARP in the brain was also associated with METH toxicity (Deng et al., 2002). Therefore, these findings suggest that METH also affects neuronal cell death via regulation of mitochondrial pathway in the brain (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

METH-induced neurotoxicity and neuroinflammation cause neuronal cell apoptosis. Neurotoxicity and neuroinflammation pathways are involved in METH-induced apoptosis. Increasing of DA and Glu by METH produce ROS and Ca2+ that act as secondary messengers for mitochondria- and ER-mediated apoptosis.

ER-Dependent Death Pathway

In addition to the mitochondria-mediated apoptosis pathway, METH is related to the ER-dependent cell death pathway (Koumenis et al., 2002; Shah and Kumar, 2016). Oxidative stress due to METH exposure can cause cellular damage by causing dysfunction of cellular organelles such as the ER (Choi et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2016). Moreover, METH-mediated oxidative stress increases the expression of ER-resident chaperones such as BiP/GRP-78, P58IPK, and heat shock protein (HSP), which are important regulators of abnormal protein folding. ER stress can initiate an unfolded protein response (UPR) to restore proteolysis or to induce apoptosis (Shen et al., 2004). ER stress is also closely linked to three major signaling molecules: (1) activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), (2) inositol requiring protein-1 (IRE-1), and (3) protein kinase RNA (PKR)-like ER kinase (PERK) (Shah and Kumar, 2016). The activity of these three molecules collectively constitutes an UPR (Tabas and Ron, 2011). ATF6 acts as a transcription factor for UPR induction, while phosphorylation of IRE-1 leads to the expression of ER-resident proteins such as BIP/GRP-78, GRP94 and C/EBP homologous proteins (CHOP)/growth arrest, and DNA damage-inducing gene 153 (Gadd153) (Tabas and Ron, 2011). In addition, PERK induces phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2α (eIF2α), which results in the stimulation of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF-4), C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP), and caspase-12 (Gorlach et al., 2006). Since the ER contains the majority of intracellular Ca2+, the released Ca2+ from the ER is absorbed by the mitochondria which then promotes ATP production (Gorlach et al., 2006).

As such, previous studies have shown that METH induces the expression of several ER stress genes, including 78kDa glucose regulated protein (GRP-78), CHOP, and ATF4, which leads to neurotoxicity in rat striatum (Bahar et al., 2016). Another study suggests that METH-induced apoptosis is mediated by ER-dependent mechanisms including CHOP, spliced X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1), caspase-12, and caspase-3 (Xiong et al., 2017). In addition, a relatively high dose of METH promotes dopaminergic neuronal apoptosis via nuclear protein 1 (Nupr1)/CHOP pathway (Xu et al., 2017). ER stress and dysregulation of calcium homeostasis appear to be involved in neuronal cell death because METH can induce the activation of calpain (Suwanjang et al., 2010). The increased calpain in METH exposure is associated with the cytoskeleton protein spectra and microtubule tau activity in rat striatum and the hippocampus (Fig. 4) (Warren et al., 2005; Staszewski and Yamamoto, 2006).

CONCLUSIONS

METH is an addictive psychostimulant that acts on the central nervous system through various physiological pathways. Chronic use of METH can lead to memory deficit, and the deterioration of attention and executive functioning, which can be attributed to the direct neurotoxic and inflammatory effects of the drug. Cumulative studies have revealed the neurological effects of METH intake, however, specific mechanisms underlying METH-mediated neuronal damages remain unclear.

In this review, we focused on the neurotoxicity and neuroinflammation caused by METH, which lead to neuronal cell death and impairment of brain function. We demonstrate that the process of neuronal damage by METH is closely related to oxidative stress, regulation of transcription factor, DNA damage, and various apoptosis pathways.

We hope that this review will help understanding the molecular mechanisms related to METH-induced brain damage and studies targeting the discovery of METH addiction therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2016R1A6A1A03011325), and by the Keimyung University Research Grant of 2018 (BDP).

References

- Abekawa T., Ohmori T., Koyama T. Effects of repeated administration of a high dose of methamphetamine on dopamine and glutamate release in rat striatum and nucleus accumbens. Brain Res. 1994;643:276–281. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ares-Santos S., Granado N., Moratalla R. The role of dopamine receptors in the neurotoxicity of methamphetamine. J. Intern. Med. 2013;273:437–453. doi: 10.1111/joim.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachtell R., Hutchinson M. R., Wang X., Rice K. C., Maier S. F., Watkins L. R. Targeting the toll of drug abuse: the translational potential of toll-like receptor 4. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets. 2015;14:692–699. doi: 10.2174/1871527314666150529132503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahar E., Kim H., Yoon H. ER stress-mediated signaling: action potential and Ca(2+) as key players. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:1558. doi: 10.3390/ijms17091558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin H. A., Colado M. I., Murray T. K., De Souza R. J., Green A. R. Striatal dopamine release in vivo following neurotoxic doses of methamphetamine and effect of the neuroprotective drugs, chlormethiazole and dizocilpine. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;108:590–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barco A., Patterson S. L., Alarcon J. M., Gromova P., Mata-Roig M., Morozov A., Kandel E. R. Gene expression profiling of facilitated L-LTP in VP16-CREB mice reveals that BDNF is critical for the maintenance of LTP and its synaptic capture. Neuron. 2005;48:123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia G., Fornai F., Busceti C. L., Aloisi G., Cerrito F., De Blasi A., Melchiorri D., Nicoletti F. Selective blockade of mGlu5 metabotropic glutamate receptors is protective against methamphetamine neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:2135–2141. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02135.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont T. L., Yao B., Shah A., Kapatos G., Loeb J. A. Layer-specific CREB target gene induction in human neocortical epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:14389–14401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3408-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauvais G., Atwell K., Jayanthi S., Ladenheim B., Cadet J. L. Involvement of dopamine receptors in binge methamphetamine-induced activation of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial stress pathways. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besnard A., Bouveyron N., Kappes V., Pascoli V., Pages C., Heck N., Vanhoutte P., Caboche J. Alterations of molecular and behavioral responses to cocaine by selective inhibition of Elk-1 phosphorylation. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:14296–14307. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2890-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billod J. M., Lacetera A., Guzman-Caldentey J., Martin-Santamaria S. Computational approaches to toll-like receptor 4 modulation. Molecules. 2016;21:994. doi: 10.3390/molecules21080994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brempelis K. J., Yuen S. Y., Schwarz N., Mohar I., Crispe I. N. Central role of the TIR-domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon-beta (TRIF) adaptor protein in murine sterile liver injury. Hepatology. 2017;65:1336–1351. doi: 10.1002/hep.29078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J. L., Jayanthi S., Deng X. Methamphetamine-induced neuronal apoptosis involves the activation of multiple death pathways. Review. Neurotox. Res. 2005;8:199–206. doi: 10.1007/BF03033973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J. L., Krasnova I. N. Molecular bases of methamphetamine-induced neurodegeneration. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2009;88:101–119. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(09)88005-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castino R., Bellio N., Nicotra G., Follo C., Trincheri N. F., Isidoro C. Cathepsin D-Bax death pathway in oxidative stressed neuroblastoma cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007;42:1305–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro A., Dirnagl U., Urra X., Planas A. M. Neuroprotection in acute stroke: targeting excitotoxicity, oxidative and nitrosative stress, and inflammation. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:869–881. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao J., Zhang Y., Du L., Zhou R., Wu X., Shen K., Yao H. Molecular mechanisms underlying the involvement of the sigma-1 receptor in methamphetamine-mediated microglial polarization. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:11540. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11065-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Rusnak M., Lombroso P. J., Sidhu A. Dopamine promotes striatal neuronal apoptotic death via ERK signaling cascades. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:287–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06590.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Huang E., Wang H., Qiu P., Liu C. RNA interference targeting alpha-synuclein attenuates methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells. Brain Res. 2013;1521:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. H., Choi A. Y., Yoon H., Choe W., Yoon K. S., Ha J., Yeo E. J., Kang I. Baicalein protects HT22 murine hippocampal neuronal cells against endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis through inhibition of reactive oxygen species production and CHOP induction. Exp. Mol. Med. 2010;42:811–822. doi: 10.3858/emm.2010.42.12.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu P. W., Seferian K. S., Birdsall E., Truong J. G., Riordan J. A., Metcalf C. S., Hanson G. R., Fleckenstein A. E. Differential regional effects of methamphetamine on dopamine transport. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008;590:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang D. K., Shin E. J., Nam Y., Ryoo S., Jeong J. H., Jang C. G., Nabeshima T., Hong J. S., Kim H. C. Apocynin prevents mitochondrial burdens, microglial activation, and pro-apoptosis induced by a toxic dose of methamphetamine in the striatum of mice via inhibition of p47phox activation by ERK. J. Neuroinflammation. 2016;13:12. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0478-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S., Vanhoutte P., Pages C., Caboche J., Laroche S. The MAPK/ERK cascade targets both Elk-1 and cAMP response element-binding protein to control long-term potentiation-dependent gene expression in the dentate gyrus in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:4563–4572. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04563.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson T. M., Dawson V. L. Mitochondrial mechanisms of neuronal cell death: potential therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017;57:437–454. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010716-105001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean A. C., Groman S. M., Morales A. M., London E. D. An evaluation of the evidence that methamphetamine abuse causes cognitive decline in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:259–274. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X., Jayanthi S., Ladenheim B., Krasnova I. N., Cadet J. L. Mice with partial deficiency of c-Jun show attenuation of methamphetamine-induced neuronal apoptosis. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002;62:993–1000. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.5.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du S. H., Qiao D. F., Chen C. X., Chen S., Liu C., Lin Z., Wang H., Xie W. B. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates methamphetamine-induced neuroinflammation through Caspase-11 signaling pathway in astrocytes. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017;10:409. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkashef A., Vocci F., Hanson G., White J., Wickes W., Tiihonen J. Pharmacotherapy of methamphetamine addiction: an update. Subst. Abus. 2008;29:31–49. doi: 10.1080/08897070802218554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyerman D. J., Yamamoto B. K. A rapid oxidation and persistent decrease in the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 after methamphetamine. J. Neurochem. 2007;103:1219–1227. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer R., Maier O. Interrelation of oxidative stress and inflammation in neurodegenerative disease: role of TNF. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015;2015:610813. doi: 10.1155/2015/610813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckenstein A. E., Volz T. J., Hanson G. R. Psychostimulant-induced alterations in vesicular monoamine transporter-2 function: neurotoxic and therapeutic implications. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56 Suppl 1:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckenstein A. E., Volz T. J., Riddle E. L., Gibb J. W., Hanson G. R. New insights into the mechanism of action of amphetamines. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007;47:681–698. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi L., Blomgren K., Kroemer G. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in neuronal injury. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009;10:481–494. doi: 10.1038/nrn2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German C. L., Hanson G. R., Fleckenstein A. E. Amphetamine and methamphetamine reduce striatal dopamine transporter function without concurrent dopamine transporter relocalization. J. Neurochem. 2012;123:288–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07875.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlach A., Klappa P., Kietzmann T. The endoplasmic reticulum: folding, calcium homeostasis, signaling, and redox control. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006;8:1391–1418. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granado N., Ares-Santos S., Moratalla R. Methamphetamine and Parkinson's disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2013;2013:308052. doi: 10.1155/2013/308052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T., Justinova Z., Hayashi E., Cormaci G., Mori T., Tsai S. Y., Barnes C., Goldberg S. R., Su T. P. Regulation of sigma-1 receptors and endoplasmic reticulum chaperones in the brain of methamphetamine self-administering rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010;332:1054–1063. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.159244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges D. M., Obray J. D., Yorgason J. T., Jang E. Y., Weerasekara V. K., Uys J. D., Bellinger F. P., Steffensen S. C. Methamphetamine induces dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens through a sigma receptor-mediated pathway. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:1405–1414. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan K. A., Staal R. G., Sonsalla P. K. Analysis of VMAT2 binding after methamphetamine or MPTP treatment: disparity between homogenates and vesicle preparations. J. Neurochem. 2000;74:2217–2220. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0742217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhak Y., Gandia C., Huang P. L., Ali S. F. Resistance of neuronal nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice to methamphetamine-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;284:1040–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhak Y., Martin J. L., Ail S. F. nNOS inhibitors attenuate methamphetamine-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity but not hyperthermia in mice. Neuroreport. 2000;11:2943–2946. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200009110-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi S., Deng X., Bordelon M., McCoy M. T., Cadet J. L. Methamphetamine causes differential regulation of pro-death and anti-death Bcl-2 genes in the mouse neocortex. FASEB J. 2001;15:1745–1752. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0025com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi S., Deng X., Noailles P. A., Ladenheim B., Cadet J. L. Methamphetamine induces neuronal apoptosis via cross-talks between endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria-dependent death cascades. FASEB J. 2004;18:238–251. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0295com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen M., Moens U. Multisite phosphorylation of the cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) by a diversity of protein kinases. Front. Biosci. 2007;12:1814–1832. doi: 10.2741/2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlig K. M., Galli A. Regulation of dopamine transporter function and plasma membrane expression by dopamine, amphetamine, and cocaine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;479:153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno M., Link J., Dennis L. E., McCready H., Huckans M., Hoffman W. F., Loftis J. M. Neuroinflammation in addiction: a review of neuroimaging studies and potential immunotherapies. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2019;179:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koumenis C., Naczki C., Koritzinsky M., Rastani S., Diehl A., Sonenberg N., Koromilas A., Wouters B. G. Regulation of protein synthesis by hypoxia via activation of the endoplasmic reticulum kinase PERK and phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2alpha. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:7405–7416. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7405-7416.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova I. N., Justinova Z., Cadet J. L. Methamphetamine addiction: involvement of CREB and neuroinflammatory signaling pathways. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2016;233:1945–1962. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4235-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzeri G., Lenzi P., Busceti C. L., Ferrucci M., Falleni A., Bruno V., Paparelli A., Fornai F. Mechanisms involved in the formation of dopamine-induced intracellular bodies within striatal neurons. J. Neurochem. 2007;101:1414–1427. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. Y., Heo J. S., Han H. J. Dopamine regulates cell cycle regulatory proteins via cAMP, Ca(2+)/PKC, MAPKs, and NF-kappaB in mouse embryonic stem cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2006;208:399–406. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. H., Wang H. J., Qiao D. F. Effect of methamphetamine on the microglial cells and activity of nitric oxide synthases in rat striatum. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2008;28:1789–1791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M., Sambo D., Khoshbouei H. Methamphetamine regulation of firing activity of dopamine neurons. J. Neurosci. 2016;36:10376–10391. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1392-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Silverstein P. S., Singh V., Shah A., Qureshi N., Kumar A. Methamphetamine increases LPS-mediated expression of IL-8, TNF-alpha and IL-1beta in human macrophages through common signaling pathways. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e33822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftis J. M., Janowsky A. Neuroimmune basis of methamphetamine toxicity. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2014;118:165–197. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801284-0.00007-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majdi F., Taheri F., Salehi P., Motaghinejad M., Safari S. Cannabinoids delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol may be effective against methamphetamine induced mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation by modulation of Toll-like type-4(Toll-like 4) receptors and NF-kappaB signaling. Med. Hypotheses. 2019;133:109371. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2019.109371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto R. R., Seminerio M. J., Turner R. C., Robson M. J., Nguyen L., Miller D. B., O'Callaghan J. P. Methamphetamine-induced toxicity: an updated review on issues related to hyperthermia. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014;144:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith C. W., Jaffe C., Ang-Lee K., Saxon A. J. Implications of chronic methamphetamine use: a literature review. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry. 2005;13:141–154. doi: 10.1080/10673220591003605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi H., Yamada K., Mizuno M., Mizuno T., Nitta A., Noda Y., Nabeshima T. Regulations of methamphetamine reward by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2/ets-like gene-1 signaling pathway via the activation of dopamine receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;65:1293–1301. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.5.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moratalla R., Khairnar A., Simola N., Granado N., Garcia-Montes J. R., Porceddu P. F., Tizabi Y., Costa G., Morelli M. Amphetamine-related drugs neurotoxicity in humans and in experimental animals: Main mechanisms. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017;155:149–170. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam Y., Wie M. B., Shin E. J., Nguyen T. T., Nah S. Y., Ko S. K., Jeong J. H., Jang C. G., Kim H. C. Ginsenoside Re protects methamphetamine-induced mitochondrial burdens and proapoptosis via genetic inhibition of protein kinase C delta in human neuroblastoma dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cell lines. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2015;35:927–944. doi: 10.1002/jat.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L., Lucke-Wold B. P., Mookerjee S. A., Cavendish J. Z., Robson M. J., Scandinaro A. L., Matsumoto R. R. Role of sigma-1 receptors in neurodegenerative diseases. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015;127:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickell J. R., Siripurapu K. B., Vartak A., Crooks P. A., Dwoskin L. P. The vesicular monoamine transporter-2: an important pharmacological target for the discovery of novel therapeutics to treat methamphetamine abuse. Adv. Pharmacol. 2014;69:71–106. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420118-7.00002-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno M., Yoshida H., Watanabe S. NMDA receptor-mediated expression of Fos protein in the rat striatum following methamphetamine administration: relation to behavioral sensitization. Brain Res. 1994;665:135–140. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panenka W. J., Procyshyn R. M., Lecomte T., MacEwan G. W., Flynn S. W., Honer W. G., Barr A. M. Methamphetamine use: a comprehensive review of molecular, preclinical and clinical findings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;129:167–179. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. H., Seo Y. H., Jang J. H., Jeong C. H., Lee S., Park B. Asiatic acid attenuates methamphetamine-induced neuroinflammation and neurotoxicity through blocking of NF-kB/STAT3/ERK and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis pathway. J. Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:240. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-1009-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle E. L., Fleckenstein A. E., Hanson G. R. Mechanisms of methamphetamine-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity. AAPS J. 2006;8:E413– E418. doi: 10.1007/BF02854914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins T. W., Ersche K. D., Everitt B. J. Drug addiction and the memory systems of the brain. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1141:1–21. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman R. B., Baumann M. H., Dersch C. M., Romero D. V., Rice K. C., Carroll F. I., Partilla J. S. Amphetamine-type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin. Synapse. 2001;39:32–41. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<32::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscher K., Wieloch T. The involvement of the sigma-1 receptor in neurodegeneration and neurorestoration. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015;127:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusyniak D. E. Neurologic manifestations of chronic methamphetamine abuse. Neurol. Clin. 2011;29:641–655. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha K., Sambo D., Richardson B. D., Lin L. M., Butler B., Villarroel L., Khoshbouei H. Intracellular methamphetamine prevents the dopamine-induced enhancement of neuronal firing. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:22246–22257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.563056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambo D. O., Lin M., Owens A., Lebowitz J. J., Richardson B., Jagnarine D. A., Shetty M., Rodriquez M., Alonge T., Ali M., Katz J., Yan L., Febo M., Henry L. K., Bruijnzeel A. W., Daws L., Khoshbouei H. The sigma-1 receptor modulates methamphetamine dysregulation of dopamine neurotransmission. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:2228. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02087-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez V., Zeini M., Camarero J., O'Shea E., Bosca L., Green A. R., Colado M. I. The nNOS inhibitor, AR-R17477AR, prevents the loss of NF68 immunoreactivity induced by methamphetamine in the mouse striatum. J. Neurochem. 2003;85:515–524. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt K. C., Reith M. E. Regulation of the dopamine transporter: aspects relevant to psychostimulant drugs of abuse. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010;1187:316–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine Y., Ouchi Y., Sugihara G., Takei N., Yoshikawa E., Nakamura K., Iwata Y., Tsuchiya K. J., Suda S., Suzuki K., Kawai M., Takebayashi K., Yamamoto S., Matsuzaki H., Ueki T., Mori N., Gold M. S., Cadet J. L. Methamphetamine causes microglial activation in the brains of human abusers. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:5756–5761. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1179-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A., Kumar A. Methamphetamine-mediated endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress induces type-1 programmed cell death in astrocytes via ATF6, IRE1alpha and PERK pathways. Oncotarget. 2016;7:46100–46119. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X., Zhang K., Kaufman R. J. The unfolded protein response--a stress signaling pathway of the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2004;28:79–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Qin H., Chen J., Mou L., He Y., Yan Y., Zhou H., Lv Y., Chen Z., Wang J., Zhou Y. D. Postnatal activation of TLR4 in astrocytes promotes excitatory synaptogenesis in hippocampal neurons. J. Cell Biol. 2016;215:719–734. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201605046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiflett M. W., Balleine B. W. Molecular substrates of action control in cortico-striatal circuits. Prog. Neurobiol. 2011;95:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin E. J., Duong C. X., Nguyen X. K., Li Z., Bing G., Bach J. H., Park D. H., Nakayama K., Ali S. F., Kanthasamy A. G., Cadet J. L., Nabeshima T., Kim H. C. Role of oxidative stress in methamphetamine-induced dopaminergic toxicity mediated by protein kinase Cdelta. Behav. Brain Res. 2012;232:98–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin E. J., Tran H. Q., Nguyen P. T., Jeong J. H., Nah S. Y., Jang C. G., Nabeshima T., Kim H. C. Role of mitochondria in methamphetamine-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity: involvement in oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and pro-apoptosis-a review. Neurochem. Res. 2018;43:66–78. doi: 10.1007/s11064-017-2318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider S. E., Hendrick E. S., Beardsley P. M. Glial cell modulators attenuate methamphetamine self-administration in the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013;701:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son J. S., Jeong Y. C., Kwon Y. B. Regulatory effect of bee venom on methamphetamine-induced cellular activities in prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens in mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2015;38:48–52. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b14-00539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonders M. S., Zhu S. J., Zahniser N. R., Kavanaugh M. P., Amara S. G. Multiple ionic conductances of the human dopamine transporter: the actions of dopamine and psychostimulants. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:960–974. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-00960.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staszewski R. D., Yamamoto B. K. Methamphetamine-induced spectrin proteolysis in the rat striatum. J. Neurochem. 2006;96:1267–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes A. H., Hastings T. G., Vrana K. E. Cytotoxic and genotoxic potential of dopamine. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;55:659–665. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990315)55:6<659::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D., Maidment N. T., Rayport S. Amphetamine and other weak bases act to promote reverse transport of dopamine in ventral midbrain neurons. J. Neurochem. 1993;60:527–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D., Pothos E., Sung H. M., Maidment N. T., Hoebel B. G., Rayport S. Weak base model of amphetamine action. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1992;654:525–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb26020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W. L., Quizon P. M., Zhu J. Molecular mechanism: ERK signaling, drug addiction, and behavioral effects. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2016;137:1–40. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwanjang W., Phansuwan-Pujito P., Govitrapong P., Chetsawang B. The protective effect of melatonin on methamphetamine-induced calpain-dependent death pathway in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cultured cells. J. Pineal Res. 2010;48:94–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabas I., Ron D. Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:184–190. doi: 10.1038/ncb0311-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tocharus J., Khonthun C., Chongthammakun S., Govitrapong P. Melatonin attenuates methamphetamine-induced overexpression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in microglial cell lines. J. Pineal Res. 2010;48:347–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng E. E., Brock M. V., Lange M. S., Troncoso J. C., Blue M. E., Lowenstein C. J., Johnston M. V., Baumgartner W. A. Glutamate excitotoxicity mediates neuronal apoptosis after hypothermic circulatory arrest. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2010;89:440–445. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E., Pascoli V., Svenningsson P., Paul S., Enslen H., Corvol J. C., Stipanovich A., Caboche J., Lombroso P. J., Nairn A. C., Greengard P., Herve D., Girault J. A. Regulation of a protein phosphatase cascade allows convergent dopamine and glutamate signals to activate ERK in the striatum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:491–496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408305102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow N. D., Chang L., Wang G. J., Fowler J. S., Leonido-Yee M., Franceschi D., Sedler M. J., Gatley S. J., Hitzemann R., Ding Y. S., Logan J., Wong C., Miller E. N. Association of dopamine transporter reduction with psychomotor impairment in methamphetamine abusers. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158:377–382. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan F., Zang S., Yu G., Xiao H., Wang J., Tang J. Ginkgolide B suppresses methamphetamine-induced microglial activation through TLR4-NF-kappaB signaling pathway in BV2 cells. Neurochem. Res. 2017;42:2881–2891. doi: 10.1007/s11064-017-2309-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. J., Smith L., Volkow N. D., Telang F., Logan J., Tomasi D., Wong C. T., Hoffman W., Jayne M., Alia-Klein N., Thanos P., Fowler J. S. Decreased dopamine activity predicts relapse in methamphetamine abusers. Mol. Psychiatry. 2012;17:918–925. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Yang X., Zhang J. Bridges between mitochondrial oxidative stress, ER stress and mTOR signaling in pancreatic beta cells. Cell Signal. 2016;28:1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren M. W., Kobeissy F. H., Liu M. C., Hayes R. L., Gold M. S., Wang K. K. Concurrent calpain and caspase-3 mediated proteolysis of alpha II-spectrin and tau in rat brain after methamphetamine exposure: a similar profile to traumatic brain injury. Life Sci. 2005;78:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong K., Long L., Zhang X., Qu H., Deng H., Ding Y., Cai J., Wang S., Wang M., Liao L., Huang J., Yi C. X., Yan J. Overview of long non-coding RNA and mRNA expression in response to methamphetamine treatment in vitro. Toxicol. In Vitro. 2017;44:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu E., Liu J., Liu H., Wang X., Xiong H. Role of microglia in methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2017;9:84–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Wang Y., Li Q., Zhong Y., Chen L., Du Y., He J., Liao L., Xiong K., Yi C. X., Yan J. The main molecular mechanisms underlying methamphetamine- induced neurotoxicity and implications for pharmacological treatment. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018;11:186. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanassi P., Paolillo M., Feliciello A., Avvedimento E. V., Gallo V., Schinelli S. cAMP-dependent protein kinase induces cAMP-response element-binding protein phosphorylation via an intracellular calcium release/ERK-dependent pathway in striatal neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:11487–11495. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007631200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J. P., Xu W., Angulo J. A. Methamphetamine-induced cell death: selective vulnerability in neuronal subpopulations of the striatum in mice. Neuroscience. 2006;140:607–622. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]