Abstract

A diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (Johnson, Schmid, Hyde, Steigerwalt & Brenner) (Spirochaetales: Spirochaetaceae) genomospecies, including the Lyme disease agent, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto (s.s.), have been identified in the western United States. However, enzootic transmission of B. burgdorferi s.l. in small mammals and ticks is poorly characterized throughout much of the region. Here we report prevalence of B. burgdorferi s.l. in small mammal and tick communities in the understudied region of southern California. We found B. burgdorferi s.l. in 1.5% of Ixodes species ticks and 3.6% of small mammals. Infection was uncommon (~0.3%) in Ixodes pacificus Cooley and Kohls (Acari: Ixodidae), the primary vector of the Lyme disease agent to humans in western North America, but a diversity of spirochetes—including Borrelia bissettiae, Borrelia californiensis, Borrelia americana, and B. burgdorferi s.s.—were identified circulating in Ixodes species ticks and their small mammal hosts. Infection with B. burgdorferi s.l. is more common in coastal habitats, where a greater diversity of Ixodes species ticks are found feeding on small mammal hosts (four species when compared with only I. pacificus in other sampled habitats). This provides some preliminary evidence that in southern California, wetter coastal areas might be more favorable for enzootic transmission than hotter and drier climates. Infection patterns confirm that human transmission risk of B. burgdorferi s.s. is low in this region. However, given evidence for local maintenance of B. burgdorferi s.l., more studies of enzootic transmission may be warranted, particularly in understudied regions where the tick vector of B. burgdorferi s.s. occurs.

Keywords: Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, Ixodes pacificus, Ixodes species, small mammal hosts, tick-borne pathogens

Lyme disease (LD) is the most common vector-borne infection in North America (Mead 2013) and is emerging in a number of regions across the Northern Hemisphere (Kugeler et al. 2015, Stone et al. 2017, Kulkarni et al. 2019). Recent studies suggest that environmental change, including changing climate (Medlock et al. 2013, Ogden et al. 2014) and land use (Larsen et al. 2014, MacDonald et al. 2019a), among other factors, contribute to range expansion of tick vectors and increased LD incidence in humans. In North America, the causative agent of LD, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto (s.s.), is vectored by two tick species, Ixodes scapularis Say (Acari: Ixodidae) in the East and Ixodes pacificus Cooley and Kohls (Acari: Ixodidae) in the West. Although these vectors are widespread, pathogen transmission to humans is highly heterogeneous throughout the ticks’ ranges (Kugeler et al. 2015, Eisen et al. 2016). This heterogeneity is due to multiple ecological and behavioral (both tick and human) factors that influence transmission in tick and host populations, and spillover to humans (Allan et al. 2003, Lane et al. 2004, Brownstein et al. 2005, Lane et al. 2013, Arsnoe et al. 2015, MacDonald and Briggs 2016, Kilpatrick et al. 2017, Salkeld et al. 2019). For example, questing behavior in nymphal I. scapularis differs regionally (Arsnoe et al. 2015), and density of infected ticks differs along forest fragmentation gradients (Allan et al. 2003), which may both influence transmission risk (Arsnoe et al. 2019, MacDonald et al. 2019a). Similarly, human risk avoidance behavior may also influence human transmission and regional patterns of LD incidence (Larsen et al. 2014, Berry et al. 2018).

The Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (s.l.) complex contains multiple genomospecies that are maintained via enzootic transmission in wild animals by ticks (Fedorova et al. 2014, Salkeld et al. 2014, Margos et al. 2016). In the western United States, tick–host–Borrelia associations are best characterized in northwestern California, where human LD risk is greatest (Fedorova et al. 2014, Salkeld et al. 2014, Rose et al. 2019). In regions where human cases are uncommon, such as southern California, the ecology of tick-borne spirochetes and their tick and small mammal hosts remains poorly characterized (MacDonald et al. 2017, MacDonald 2018). Studies in these regions might offer insight into the ecological factors that differentiate areas of high and low LD risk (Lane and Quistad 1998, Lane et al. 2013, Arsnoe et al. 2015, Rose et al. 2019).

Here we summarize preliminary evidence for enzootic transmission of B. burgdorferi s.l. in small mammals and Ixodes ticks in the understudied region of southern California, within the range of I. pacificus (Eisen et al. 2018, MacDonald et al. 2019b). We find evidence for multiple circulating genomospecies, including B. burgdorferi s.s., but find little evidence for human disease risk due to low infection prevalence in the human vector, I. pacificus. These preliminary results help characterize regional variation in enzootic transmission of tick-borne spirochetes in understudied regions of western North America, and provide preliminary data highlighting avenues for future investigation into the ecological factors that influence transmission in these regions.

Methods

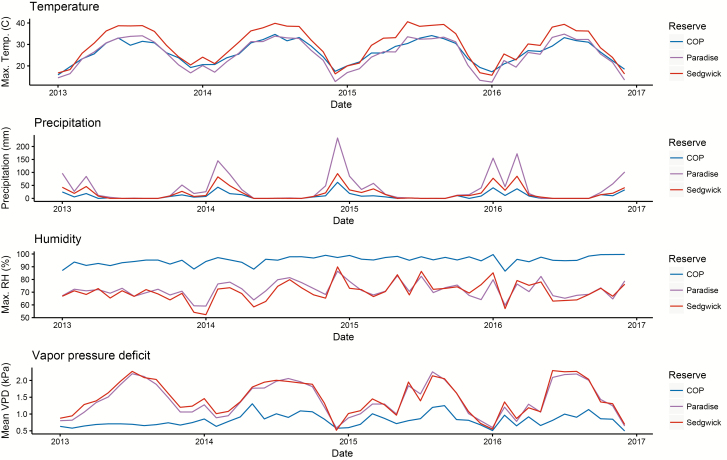

To investigate enzootic circulation of B. burgdorferi s.l. in southern California, rodents and Ixodes species ticks were sampled at three ecological reserves in Santa Barbara County: Sedgwick Reserve in the Santa Ynez Valley (34°42′04.38″ N, 120°02′50.81″ W), Paradise Reserve in the Santa Ynez Mountains (34°32′22.07″ N, 119°47′51.89″ W), and Coal Oil Point (COP) Reserve along the coast (34°24′52.96″ N, 119°52′48.59″ W; Fig. 1). These three sites represent a range of common habitats and abiotic conditions in southern California (MacDonald et al. 2017). COP is dominated by coastal scrub, grassland and coast live oak habitats, and experiences a significant marine influence, leading to elevated relative humidity and lower vapor pressure deficit throughout the year (Fig. 1). Sedgwick is located in an inland valley and is dominated by oak woodland, savannah and chaparral/scrub habitats, and experiences colder winters and warmer, drier summers (Fig. 1). Paradise is located on the north face of the Santa Ynez Mountains and is dominated by dense oak woodland with some open grassland and chaparral/scrub habitat, and experiences intermediate marine influence (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Meteorological data summarized for Coal Oil Point (COP), Paradise and Sedgwick Reserves from 2013 to 2016. Temperature is from MODIS land surface temperature, precipitation is from the Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Station data (CHIRPS; Funk et al. 2015), and both relative humidity and vapor pressure deficit are from the University of Idaho Gridded Surface Meteorological Dataset (GRIDMET; Abatzoglou 2013). All data were accessed and processed through the Google Earth Engine Platform (Gorelick et al. 2017). Temperature is lower at the coastal site (COP) and high relative humidity and low vapor pressure deficit at this site suggest it has higher moisture availability throughout the year than the two inland sites.

Tick sampling was conducted from November through June of 2013–2016. Questing ticks were collected weekly to monthly at each site by dragging a 1m2 white flannel cloth along the ground and over low-lying vegetation within a stratified random sample of 2500m2 plots that were established to capture habitat and microclimate heterogeneity within each reserve. Ticks were placed in vials containing 70% ethanol and identified to species, sex and life stage using a dichotomous key (Furman and Loomis 1984).

Rodents were captured using Sherman live traps (7.6 × 9.5 × 30.5 cm; H.B. Sherman Traps, Tallahassee, FL) baited with peanut butter and oats. At Sedgwick and Paradise, ear punch biopsies were collected from each rodent and stored in 70% ethanol, and animals were released at the point of capture (MacDonald et al. 2018). At COP, rodents were trapped and euthanized for a separate study (Weinstein 2017) and tissue samples were collected during necropsy. Attached ticks were collected from each captured rodent and identified to species to characterize tick–host associations. Rodent sampling took place from January through June of 2014 at Sedgwick and Paradise, and throughout the year from 2013 to 2016 at COP. Sedgwick and COP were sampled monthly using a haphazard placement of 30 traps per sampling event (see Weinstein 2017). Paradise was sampled monthly using a 10 × 10 grid of 200 traps, set for three consecutive nights (see MacDonald et al. 2018). Since trapped mammals may not reflect the entire community of potential small mammal hosts at each of these sites, we use modeled species ranges from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) Areas of Conservation Emphasis (ACE) Program to compare species richness and community composition of small mammals between sites (data available at https://wildlife.ca.gov/Data/Analysis/Ace.

DNA was extracted from questing adult and nymphal Ixodes species ticks and from rodent tissue samples using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) following manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were screened for spirochetes in the B. burgdorferi s.l. group via nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeting the 5S-23S rRNA spacer region of all spirochetes belonging to this group following Lane et al. (2004). Negative extraction controls as well as positive and negative PCR controls were included in all PCR assays to identify possible sources of contamination. PCR-positive samples were sequenced at the 5S-23S intergenic spacer region (2004), on an AB 3100 (Applied Biosystems, CA).

Results

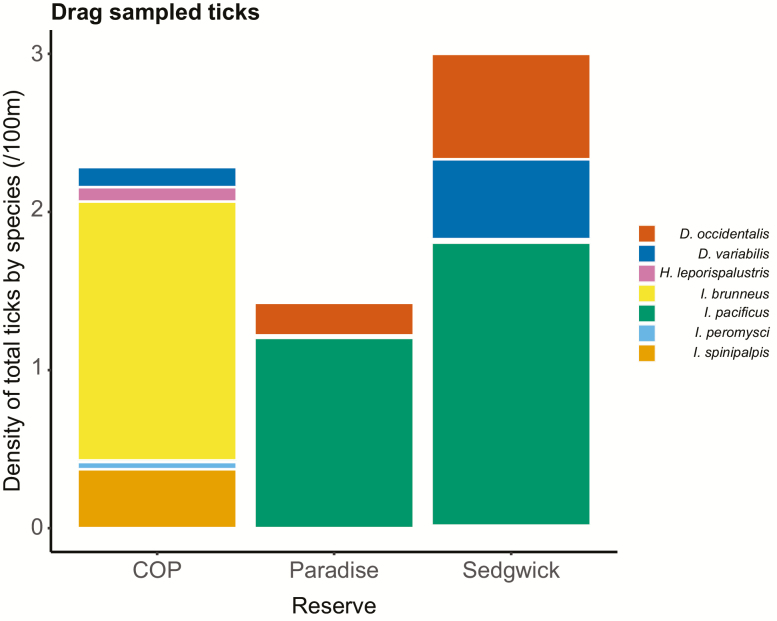

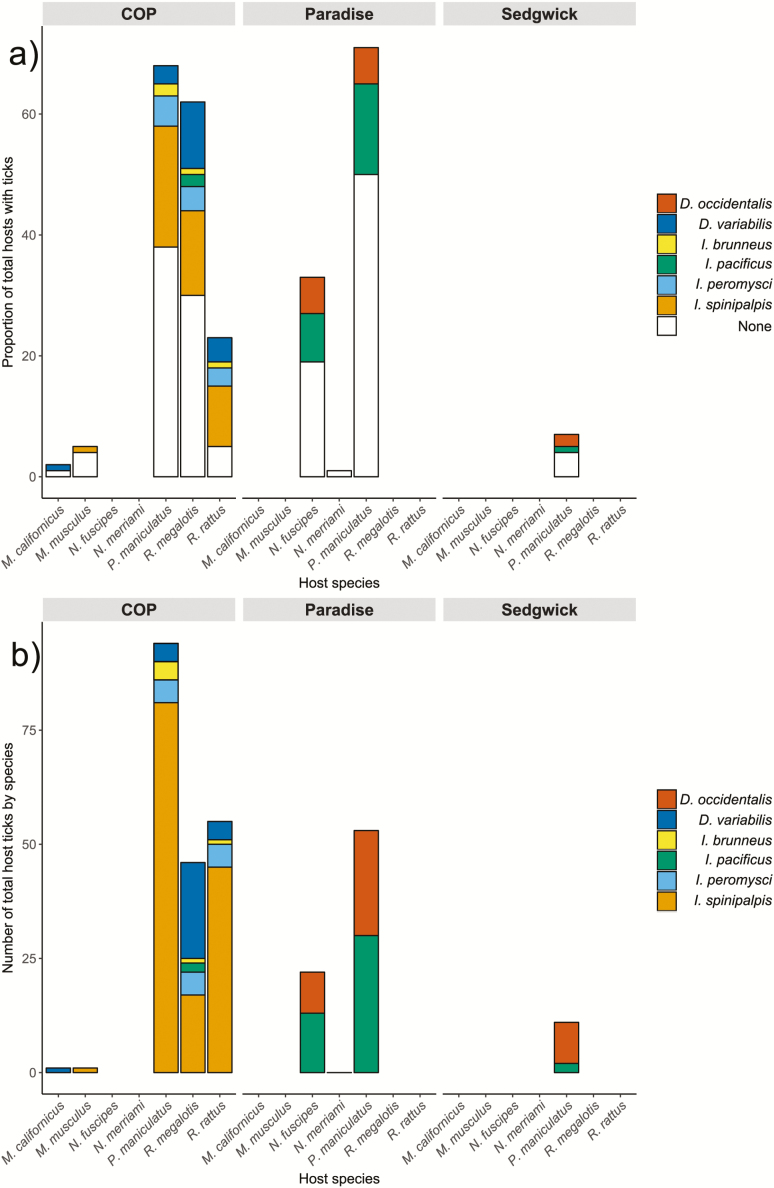

Across the three reserves, seven tick species, including four Ixodes species, were collected via drag sampling, reflecting differing tick community composition between sites (Fig. 2). Most notably, abundance of non–I. pacificus species of Ixodes ticks was much higher at COP (Fig. 2). Overall, small mammal host communities are not expected to differ substantially between sites, based on ACE data, although there are important exceptions: dusky-footed woodrats (Neotoma fuscipes Baird [Rodentia: Cricetidae]) are not expected to be present at COP or Sedgwick, but are at Paradise; western gray squirrels (Sciurus griseus Ord [Rodentia: Sciuridae]) are not expected to be present at COP, but are at Sedgwick and Paradise (Table 1). In total, seven species of small mammal were collected and sampled host diversity (Shannon’s H) was higher at COP than the other sites (Table 2), although overall expected richness, from the ACE data, is similar (Table 1). At Paradise and Sedgwick, the most common ticks found feeding on small mammals were Dermacentor occidentalis Marx (Acari: Ixodidae) and I. pacificus (Fig. 3a), which were found in roughly equal proportions on N. fuscipes (Paradise) and Peromyscus maniculatus Wagner (Rodentia: Cricetidae) (Paradise and Sedgwick; Fig. 3b). In contrast, Ixodes spinipalpis Hawden & Nuttall (Acari: Ixodidae) was the most commonly attached tick feeding on small mammals at COP (Fig. 3) where richness of host-feeding ticks was higher (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Density of drag sampled ticks per 100 m2 at each sampled reserve. The height of the bar reflects overall density with the proportion of total density of each species of tick reflected by the colors within each bar. Ixodes pacificus, Ixodes peromysci, Ixodes brunneus, Ixodes spinipalpis, Dermacentor variabilis, and Haemaphysalis leporispalustris were collected at Coal Oil Point Reserve; I. pacificus, I. brunneus, and Dermacentor occidentalis were collected at Paradise Reserve; I. pacificus, I. brunneus, I. spinipalpis, D. variabilis, D. occidentalis, and H. leporispalustris were collected at Sedgwick Reserve.

Table 1.

Small mammal host communities at each sampled reserve, based on modeled species ranges and habitat suitability from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) Areas of Conservation Emphasis (ACE) Program

| Species (common name) | Reserve | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| COP | Paradise | Sedgwick | |

| Chaetodipus californicus (california pocket mouse) | x | x | x |

| Dipodomys agilis (agile kangaroo rat) | x | x | x |

| Lepus californicus (black-tailed jackrabbit) | x | x | x |

| Microtus californicus (california vole) | x | x | x |

| Neotoma fuscipes (dusky-footed woodrat) | NA | x | NA |

| Neotoma lepida (desert woodrat) | x | x | x |

| Neotoma macrotis (big-eared woodrat) | x | x | x |

| Ostospermophilus beecheyi (california ground squirrel) | x | x | x |

| Peromyscus boylii (brush mouse) | x | x | x |

| Peromyscus californicus (california mouse) | x | x | x |

| Peromyscus maniculatus (deer mouse) | x | x | x |

| Reithrodontomys megalotis (western harvest mouse) | x | x | x |

| Scapanus latimanus (broad-footed mole) | x | x | x |

| Sciurus griseus (western gray squirrel) | NA | x | x |

| Sorex ornatus (ornate shrew) | x | x | x |

| Sorex trowbridgii (trowbridge’s shrew) | x | x | x |

| Sylvilagus audubonii (audubon’s cottontail) | x | x | x |

| Sylvilagus bachmani (brush rabbit) | x | x | x |

| Tamias merriami (merriam’s chipmunk) | x | x | x |

| Thomomys bottae (botta’s pocket gopher) | x | x | x |

Table 2.

Tick and host species richness and diversity at each sampled reserve

| Reserve | Species richness | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dragged ticks (H) | Mammal ticks (H) | Trapped hosts (H) | Hosts (small mam.) | Hosts (all) | All vertebrates | |

| Coal Oil Point | 6 (0.315) | 5 (0.865) | 5 (1.163) | 18 | 66 | 284 |

| Paradise | 3 (0.329) | 2 (0.682) | 3 (0.660) | 20 | 72 | 237 |

| Sedgwick | 6 (0.613) | 2 (0.474) | 1 (0) | 19 | 68 | 238 |

The first three columns of data are from sampled tick and host communities and include a measure of diversity (Shannon’s H). The last three columns are from modeled species ranges and habitat suitability based on CDFW ACE data, and richness is presented for 1) just small mammal hosts, 2) all potential vertebrate hosts including reptiles and ground foraging birds, and 3) all vertebrate species found in each reserve.

Fig. 3.

Tick–host associations in the three sampled reserves. (a) illustrates the proportion of the total number of individual hosts of each species captured that were found with each host-feeding tick species attached; (b) illustrates the total number of ticks of each species found feeding on each species of host.

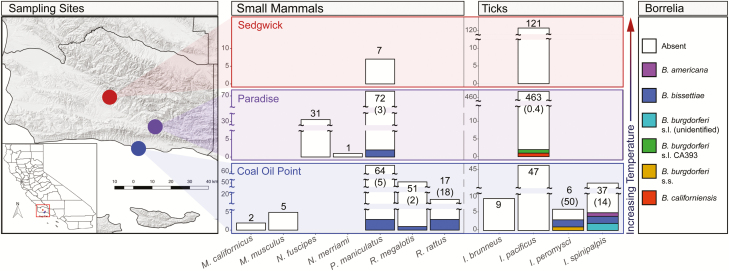

In total, 683 questing Ixodes species ticks and 250 rodents were screened for infection. Ten of 683 ticks (~1.5%) and nine of 250 rodents (3.6%) had evidence of infection with B. burgdorferi s.l. (Fig. 4; Tables 3 and 4). Borrelia bissettiae, a species with some limited evidence as a potential human pathogen in northwestern California and eastern Europe (Girard et al. 2011), was the most common genomospecies infecting ticks in this region (Fig. 4; Tables 3 and 4), but was not found in I. pacificus. Borrelia bissettiae was the only genomospecies found infecting small mammals in this study as well (Tables 3 and 4). Borrelia burgdorferi s.s. was only detected in a single Ixodes peromysci Augustson (Acari: Ixodidae) tick from the coastal reserve and was not found in any rodents. Most infections were found in rodent specialist Ixodes species, primarily I. spinipalpis, and in rodents from the coastal reserve, most commonly the invasive black rat (Rattus rattus Linnaeus [Rodentia: Muridae]; Fig. 4; Tables 3 and 4). The only infected I. pacificus ticks were collected from the mountain reserve, where only P. maniculatus hosts were found to be infected with B. burgdorferi s.l. No dusky-footed woodrats (N. fuscipes), implicated as reservoirs for B. burgdorferi s.s. (Lane and Brown 1991, Swei et al. 2012), were infected with B. burgdorferi s.l. at this site. No infected ticks or hosts were detected from the inland valley reserve, though host sampling effort was more limited at this site.

Fig. 4.

Map of study sites in Santa Barbara County and visual summary of infection results by site. The total number of screened individuals of each species are at the top of each bar, with Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. infection prevalence in parentheses below.

Table 3.

Summary of tick and rodent infection prevalence with Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. spirochetes in Santa Barbara County, USA

| Collection location | Ticks or hosts | Species | No. of infected/total tested (%) | Previously reported | Accession numbers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. bissettiae | B. californiensis | B. americana | B. burgdorferi s.l. CA393 | B. burgdorferi s.l. (unidentified) | B. burgdorferi s.s. | All Borrelia species | |||||

| Coal Oil Point Reserve (Coastal) | Ticks | I. pacificus | 0/47 (0%) | Y | |||||||

| I. brunneus | 0/9 (0%) | Y | |||||||||

| I. peromysci | 2/6 (33%) | 1/6 (16.67%) | 3/6 (50%) | Y | KY271962, KY271963, KY271964 | ||||||

| I. spinipalpis | 2/37 (5.41%) | 1/37 (2.7%) | 2/37 (5.41%) | 5/37 (13.5%) | In part | KY271965, MK908067, MK932858, MK932859, MK932860 | |||||

| Hosts | R. megalotis | 1/51 (1.96%) | 1/51 (1.96%) | N | MK908061 | ||||||

| P. maniculatus | 3/64 (4.69%) | 3/64 (4.69%) | N | MK908062, MK908063, MK908064 | |||||||

| M. musculus | 0/5 (0%) | N | |||||||||

| M. californicus | 0/2 (0%) | N | |||||||||

| R. rattus | 3/17 (17.65%) | 3/17 (17.65%) | N | MK908065, MK908066, MK932857 | |||||||

| Paradise Reserve (Coastal Mountains) | Ticks | I. pacificus | 1/463 (0.22%) | 1/463 (0.22%) | 2/463 (0.43%) | In part | KY350558, KY350559 | ||||

| Hosts | N. fuscipes | 0/31 (0%) | Y | ||||||||

| N. merriami | 0/1 (0%) | Y | |||||||||

| P. maniculatus | 2/72 (2.78%) | 2/72 (2.78%) | Y | KY350560, KY350561 | |||||||

| Sedgwick Reserve (Inland Valley) | Ticks | I. pacificus | 0/121 (0%) | Y | |||||||

| Hosts | P. maniculatus | 0/7 (0%) | N |

Tick species collected and screened include Ixodes pacificus, Ixodes brunneus, Ixodes peromysci, and Ixodes spinipalpis; rodent species include Reithrodontomys megalotis, Peromyscus maniculatus, Mus musculus, Microtus californicus, Rattus rattus, Neotoma fuscipes, and Neotamias merriami. Some infection results were previously reported in earlier studies, including tick infection results from Sedgwick Reserve (MacDonald et al. 2017), rodent and a subset of tick infection results from Paradise Reserve (MacDonald et al. 2018), and a subset of tick infection results from Coal Oil Point Reserve (MacDonald et al. 2017).

* s.l. = sensu lato; s.s. = sensu stricto.

Table 4.

Summary of overall infection prevalence by Borrelia genomospecies and tick and host species across all sampled sites

| Tick and host species | Borrelia species, overall prevalence (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. bissettiae | B. californiensis | B. americana | B. burgdorferi s.l. CA393 | B. burgdorferi s.l. (unidentified) | B. burgdorferi s.s. | All Borrelia species | |

| I. pacificus | 0/631 (0%) | 1/631 (0.16%) | 0/631 (0%) | 1/631 (0.16%) | 0/631 (0%) | 0/631 (0%) | 2/631 (0.32%) |

| I. brunneus | 0/9 (0%) | 0/9 (0%) | 0/9 (0%) | 0/9 (0%) | 0/9 (0%) | 0/9 (0%) | 0/9 (0%) |

| I. peromysci | 2/6 (33%) | 0/6 (0%) | 0/6 (0%) | 0/6 (0%) | 0/6 (0%) | 1/6 (16.67%) | 3/6 (50%) |

| I. spinipalpis | 2/37 (5.4%) | 0/37 (0%) | 1/37 (2.7%) | 0/37 (0%) | 2/37 (5.4%) | 0/37 (0%) | 5/37 (13.5%) |

| Total ticks | 4/683 (0.6%) | 1/683 (0.15%) | 1/683 (0.15%) | 1/683 (0.15%) | 2/683 (0.3%) | 1/683 (0.15%) | 10/683 (1.5%) |

| R. megalotis | 1/51 (1.96%) | 0/51 (0%) | 0/51 (0%) | 0/51 (0%) | 0/51 (0%) | 0/51 (0%) | 1/51 (1.96%) |

| P. maniculatus | 5/143 (3.5%) | 0/143 (0%) | 0/143 (0%) | 0/143 (0%) | 0/143 (0%) | 0/143 (0%) | 5/143 (3.5%) |

| M. musculus | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) |

| M. californicus | 0/2 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) |

| R. rattus | 3/17 (17.65%) | 0/17 (0%) | 0/17 (0%) | 0/17 (0%) | 0/17 (0%) | 0/17 (0%) | 3/17 (17.65%) |

| N. fuscipes | 0/31 (0%) | 0/31 (0%) | 0/31 (0%) | 0/31 (0%) | 0/31 (0%) | 0/31 (0%) | 0/31 (0%) |

| N. merriami | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) |

| Total hosts | 9/250 (3.6%) | 0/250 (0%) | 0/250 (0%) | 0/250 (0%) | 0/250 (0%) | 0/250 (0%) | 9/250 (3.6%) |

Discussion

Although LD is recognized as an emerging infectious disease across the Northern Hemisphere (Steere et al. 2004, Mead 2013, Kugeler et al. 2015), circulation of B. burgdorferi s.l. spirochetes in tick and host communities remains poorly characterized throughout much of this range. Here we report infection in Ixodes ticks and small mammal hosts at three ecological reserves in southern California. We found multiple B. burgdorferi s.l. species circulating, and infection prevalence was higher at a coastal site with the greatest Ixodes tick species richness and diversity, and where small mammal hosts had higher burdens of these species, perhaps due to more favorable abiotic conditions including higher and stable humidity and limited temperature extremes (Fig. 1). Among sampled ticks, B. burgdorferi s.l. infection was highest in the rodent specialist species I. spinipalpis and I. peromysci. These tick species heavily parasitized P. maniculatus and R. rattus, and B. bissettiae was detected in these ticks and hosts where they co-occurred. These results provide preliminary evidence that enzootic transmission of B. burgdorferi s.l. may be maintained in nontraditional cycles in coastal southern California, for example, I. spinipalpis feeding on P. maniculatus. Borrelia burgdorferi s.s. in contrast was found in only a single tick at the coastal site. This observation, combined with low rates of any B. burgdorferi s.l. infection in the primary human vector, I. pacificus, likely contributes to low human disease incidence in this region. However, while these results and other recent studies imply that human transmission risk is low in southern California (Lane et al. 2013, MacDonald et al. 2017, Rose et al. 2019), enzootic transmission in wild animals may not be.

Higher infection prevalence in ticks and mammals from the coastal site provides some preliminary evidence that enzootic transmission in southern California might be higher in coastal areas with more marine influence. Coastal regions are comparatively cool and wet, which may increase tick survivorship and host-seeking activity, as well as support competent tick vectors and mammalian hosts, increasing pathogen transmission (MacDonald et al. 2017). Given substantial regional and local heterogeneity observed in abundance and infection in ticks in California (Tälleklint-Eisen and Lane 1999), localized enzootic transmission of B. burgdorferi s.l. may be common throughout western North America. Although vector and host competence studies are needed to determine which species contribute to enzootic transmission cycles in southern California, our results suggest that multiple host (e.g., P. maniculatus and R. rattus) and vector (e.g., I. peromysci and I. spinipalpis) species may contribute to enzootic transmission and maintenance of B. burgdorferi s.l. in southern California. Future studies should focus on characterizing vector–host–pathogen associations across a gradient of climate and habitat types in this region, as well as conducting competency studies based on these associations.

Under current climate conditions, spillover of B. burgdorferi s.l. to humans is rare in southern California; however, environmental change may influence future transmission dynamics. Host–parasite interactions could shift in response to changing climate or land use (Paull et al. 2012). For example, ticks are more sensitive to temperature than their small mammal hosts, and may be more likely to exhibit population declines, range shifts or changes in host-seeking phenology with increasing temperature and aridity predicted for many regions of California, leading to more limited local transmission of spirochetes between ticks and hosts. On the other hand, under climate change scenarios that predict overall increases in the amount and volatility of precipitation in California (Swain et al. 2018), I. pacificus populations or seasonal periods of activity may increase in response to particularly wet years, elevating spillover transmission risk in regions where enzootic transmission is maintained. As the specific tick–host associations responsible for enzootic maintenance of B. burgdorferi s.l. remain poorly understood in many regions, we suggest more careful study of this system across the full range of I. pacificus to characterize enzootic transmission and identify where spillover transmission could occur.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the University of California Natural Reserve System and Dr. Cris Sandoval and Dr. Kevin Lafferty for access to field sites. We also thank Dr. Cherie Briggs for supporting this research as well as two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript. All small mammal sampling was conducted in accordance with UC Santa Barbara Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols #863 and #850, as well as California Department of Fish and Game Scientific Collecting Permits #SC-12329 and #SC-11188.

References Cited

- Allan B. F., Keesing F., and Ostfeld R. S.. 2003. Effect of forest fragmentation on Lyme disease risk. Conserv. Biol. 17: 267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Arsnoe I. M., Hickling G. J., Ginsberg H. S., McElreath R., and Tsao J. I.. 2015. Different populations of blacklegged tick nymphs exhibit differences in questing behavior that have implications for human lyme disease risk. PLoS One. 10: e0127450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsnoe I., Tsao J. I., and Hickling G. J.. 2019. Nymphal Ixodes scapularis questing behavior explains geographic variation in Lyme borreliosis risk in the eastern United States. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 10: 553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry K., Bayham J., Meyer S. R., and Fenichel E. P.. 2018. The allocation of time and risk of Lyme: a case of ecosystem service income and substitution effects. Environ. Resour. Econ. (Dordr). 70: 631–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownstein J. S., Skelly D. K., Holford T. R., and Fish D.. 2005. Forest fragmentation predicts local scale heterogeneity of Lyme disease risk. Oecologia. 146: 469–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen R. J., Eisen L., Ogden N. H., and Beard C. B.. 2016. Linkages of weather and climate with Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae), enzootic transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi, and Lyme disease in North America. J. Med. Entomol. 53: 250–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen R. J., Feirer S., Padgett K. A., Hahn M. B., Monaghan A. J., Kramer V. L., Lane R. S., and Kelly M.. 2018. Modeling climate suitability of the western blacklegged tick in California. J. Med. Entomol. 22: 42–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorova N., Kleinjan J. E., James D., Hui L. T., Peeters H., and Lane R. S.. 2014. Remarkable diversity of tick or mammalian-associated Borreliae in the metropolitan San Francisco Bay Area, California. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 5: 951–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk C., Peterson P., Landsfeld M., Pedreros D., Verdin J., Shukla S., Husak G., Rowland J., Harrison L., Hoell A., . et al. 2015. The climate hazards infrared precipitation with stations–a new environmental record for monitoring extremes. Sci. Data. 2: 150066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman D. P., and Loomis E. C.. 1984. The ticks of California: Acari: Ixodida. Bulletin of the California Insect Survey. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Girard Y. A., Fedorova N., and Lane R. S.. 2011. Genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi and detection of B. bissettii-like DNA in serum of north-coastal California residents. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49: 945–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick N., Hancher M., Dixon M., Ilyushchenko S., Thau D., and Moore R.. 2017. Google earth engine: planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 202: 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick A. M., Dobson A. D. M., Levi T., Salkeld D. J., Swei A., Ginsberg H. S., Kjemtrup A., Padgett K. A., Jensen P. M., Fish D., . et al. 2017. Lyme disease ecology in a changing world: consensus, uncertainty and critical gaps for improving control. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 372: 20160117–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugeler K. J., Farley G. M., Forrester J. D., and Mead P. S.. 2015. Geographic distribution and expansion of human Lyme disease, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 21: 1455–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni M. A., Narula I., Slatculescu A. M., and Russell C.. 2019. Lyme disease emergence after invasion of the blacklegged tick, Ixodes scapularis, Ontario, Canada, 2010–2016. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 25: 328–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane R. S., and Brown R. N.. 1991. Wood rats and kangaroo rats: potential reservoirs of the Lyme disease spirochete in California. J. Med. Entomol. 28: 299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane R. S., and Quistad G. B.. 1998. Borreliacidal factor in the blood of the western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis). J. Parasitol. 84: 29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane R. S., Steinlein D. B., and Mun J.. 2004. Human behaviors elevating exposure to Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae) nymphs and their associated bacterial zoonotic agents in a hardwood forest. J. Med. Entomol. 41: 239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane R. S., Fedorova N., Kleinjan J. E., and Maxwell M.. 2013. Eco-epidemiological factors contributing to the low risk of human exposure to ixodid tick-borne borreliae in southern California, USA. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 4: 377–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen A. E., MacDonald A. J., and Plantinga A. J.. 2014. Lyme disease risk influences human settlement in the wildland-urban interface: evidence from a longitudinal analysis of counties in the northeastern United States. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 91: 747–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald A. J. 2018. Abiotic and habitat drivers of tick vector abundance, diversity, phenology and human encounter risk in southern California. PLoS One. 13: e0201665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald A. J., and Briggs C. J.. 2016. Truncated seasonal activity patterns of the western blacklegged tick (Ixodes pacificus) in central and southern California. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 7: 234–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald A. J., Hyon D. W., Brewington J. B. 3rd, O’Connor K. E., Swei A., and Briggs C. J.. 2017. Lyme disease risk in southern California: abiotic and environmental drivers of Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae) density and infection prevalence with Borrelia burgdorferi. Parasit. Vectors. 10: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald A. J., Hyon D. W., McDaniels A., O’Connor K. E., Swei A., and Briggs C. J.. 2018. Risk of vector tick exposure initially increases, then declines through time in response to wildfire in California. Ecosphere. 9: e02227–20. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald A. J., Larsen A. E., and Plantinga A. J.. 2019a. Missing the people for the trees: Identifying coupled natural-human system feedbacks driving the ecology of Lyme disease. J. Appl. Ecol. 56: 354–364. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald A. J., O’Neill C., Yoshimizu M. H., Padgett K. A., and Larsen A. E.. 2019b. Tracking seasonal activity of the western blacklegged tick across California. J. Appl. Ecol. 56: 2562–2573. [Google Scholar]

- Margos G., Lane R. S., Fedorova N., Koloczek J., Piesman J., Hojgaard A., Sing A., and Fingerle V.. 2016. Borrelia bissettiae sp. nov. and Borrelia californiensis sp. nov. prevail in diverse enzootic transmission cycles. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 66: 1447–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead P. S. 2013. Estimating the public health burden of Lyme disease in the United States. In Presented at the 13th International Conference on Lyme Borreliosis and Other Tick-Borne Diseases, 18–21 August 2013, Boston, MA.

- Medlock J. M., Hansford K. M., Bormane A., Derdakova M., Estrada-Peña A., George J. C., Golovljova I., Jaenson T. G., Jensen J. K., Jensen P. M., . et al. 2013. Driving forces for changes in geographical distribution of Ixodes ricinus ticks in Europe. Parasit. Vectors. 6: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden N. H., Radojevic M., Wu X., Duvvuri V. R., Leighton P. A., and Wu J.. 2014. Estimated effects of projected climate change on the basic reproductive number of the Lyme disease vector Ixodes scapularis. Environ. Health Perspect. 122: 631–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paull S. H., LaFonte B. E., and Johnson P. T. J.. 2012. Temperature-driven shifts in a host-parasite interaction drive nonlinear changes in disease risk. Glob. Change Biol. 18: 3558–3567. [Google Scholar]

- Rose I., Yoshimizu M. H., Bonilla D. L., Fedorova N., Lane R. S., and Padgett K. A.. 2019. Phylogeography of Borrelia spirochetes in Ixodes pacificus and Ixodes spinipalpis ticks highlights differential acarological risk of tick-borne disease transmission in northern versus southern California. PLoS One. 14: e0214726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkeld D. J., Cinkovich S., and Nieto N. C.. 2014. Tick-borne pathogens in northwestern California, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 20: 493–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkeld D. J., Porter W. T., Loh S. M., and Nieto N. C.. 2019. Time of year and outdoor recreation affect human exposure to ticks in California, United States. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 10: 1113–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steere A. C., Coburn J., and Glickstein L.. 2004. The emergence of Lyme disease. J. Clin. Invest. 113: 1093–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone B. L., Tourand Y., and Brissette C. A.. 2017. Brave new worlds: the expanding universe of Lyme disease. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 17: 619–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain D. L., Langenbrunner B., Neelin J. D., and Hall A.. 2018. Increasing precipitation volatility in twenty-first- century California. Nat. Clim. Change. 8: 427–433. [Google Scholar]

- Swei A., Briggs C. J., Lane R. S., and Ostfeld R. S.. 2012. Impacts of an introduced forest pathogen on the risk of Lyme disease in California. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 12: 623–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tälleklint-Eisen L., and Lane R. S.. 1999. Variation in the density of questing Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae) nymphs infected with Borrelia burgdorferi at different spatial scales in California. J. Parasitol. 85: 824–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein S. B. 2017. Introduced rats and an endemic roundworm: does rattus rattus contribute to Baylisascaris procyonis transmission in California? J. Parasitol. 103: 677–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]