Abstract

Background

Essential Tremor (ET) is likely the most frequent movement disorder. In this review, we have summarized the current pharmacological options for the treatment of this disorder and discussed several future options derived from drugs tested in experimental models of ET or from neuropathological data.

Methods

A literature search was performed on the pharmacology of essential tremors using PubMed Database from 1966 to July 31, 2019.

Results

To date, the beta-blocker propranolol and the antiepileptic drug primidone are the drugs that have shown higher efficacy in the treatment of ET. Other drugs tested in ET patients have shown different degrees of efficacy or have not been useful.

Conclusion

Injections of botulinum toxin A could be useful in the treatment of some patients with ET refractory to pharmacotherapy. According to recent neurochemical data, drugs acting on the extrasynaptic GABAA receptors, the glutamatergic system or LINGO-1 could be interesting therapeutic options in the future.

Keywords: Essential tremor, neuropharmacology, beta-blockers, primidone, antiepileptic drugs, gap-junction blockers, experimental treatment

1. Introduction

Essential Tremor (ET), which is likely the most frequent movement disorder, is characterized by postural or kinetic tremor at 4–12 Hz involving mainly upper extremities. In some ET patients, tremor can spread to other locations, including the head, laryngeal muscles (causing voice tremor), tongue and lower extremities. The etiology of ET is not well known, although the contribution of both genetic and environmental factors has been suggested [1-3]. The neurochemical mechanisms of ET are also unknown, with the most consistent data related to the GABAergic and glutamatergic systems, with a lesser contribution of adrenergic and dopaminergic systems, and adenosine [4].

ET requires treatment when the tremor causes functional disabilities (i.e. difficulty to write, to threading a needle or other tasks which require precision, pouring liquids from a spoon or a glass, etc.) or embarrassing social situations. It is well known that many patients with ET show a good pharmacological response to ethanol [5-8], but the effect of ethanol on tremor is usually transitory, and often causes a rebound phenomenon, carrying a potential risk for chronic alcoholism. The beta-blocker propranolol and the antiepileptic primidone are (for many years up to date) the most efficacious drugs for the symptomatic treatment of ET affecting the upper extremities (the therapeutic response of head or voice tremor is poorer), while other drugs have shown a variable degree of efficacy.

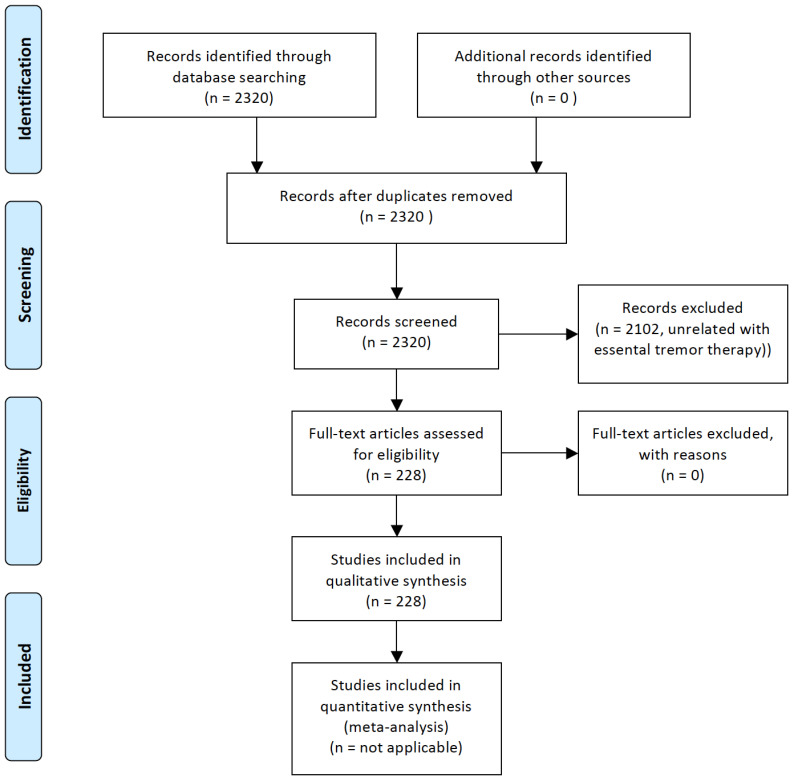

This review focuses on the current pharmacological therapy of ET, and future perspectives of pharmacological treatments inferred from the effect of certain drugs in experimental models of ET. The main aim is to provide an extensive descriptive review of studies reporting data on pharmacological therapy of patients with ET and in experimental models of ET, summarizing their main conclusions, updating previous information, and including new drugs [9-11]. For this purpose, we performed a search in the PubMed Database from 1966 until July 31, 2019, by crossing the term “essential tremor” with “pharmacology” (631 items), “neuropharmacology” (9 items), “treatment” (2163 items), “therapy” (1891 items), “propranolol” (263 items), “metoprolol” (27 items), “atenolol” (19 items), “nadolol” (7 items) “indenolol” (1 item), “sotalol” (9 items), “timolol” (4 items) “arotinolol” (6 items), “pindolol” (5 items), “primidone” (160 items), phenobarbital (100 items), T2000 (2 items), “gabapentin” (52 items), “tiagabine” (3 items), “topiramate” (58 items), “levetiracetam” (20 items), “zonisamide” (17 items), “pregabalin” (11 items), “lacosamide” (2 items), “ethosuximide” (4 items), “perampanel” (1 item), “oxcarbazepine” (5 items), “carisbamate” (2 items), “nifedipine” (2 items), “flunarizine” (15 items), “nicardipine” (2 items), “nimodipine” (6 items), “calcium channel blockers” (49 items), “alprazolam” (15 items), “clonazepam” (39 items), “heptanol” (1 items), “octanol” (13 items), “octanoid acid” (7 items), “neuroleptic drugs” (37 items), “olanzapine” (4 items), “clozapine” (11 items), “quetiapine” (2 items), “antiparkinsonian drugs” (123 items), “carbonic anhidrase inhibitors” (14 items), “botulinum toxin” (124 items), “adenosine” (19 items), “glutamate” (45 items), “serotonin” (25 items), and “alpha-adrenergic drugs” (13 items). The full search retrieved a total of 2320 references. We selected the references of interest, considering as references of interest those studies related to pharmacological therapies in patients with ET or in experimental models of ET, by examining one by one the content of these articles. The flowchart for the selection of the studies, following the PRISMA guidelines [12], is represented in Fig. 1. Recently, the Movement Disorders Society (MDS) Task Force on Tremor and the MDS Evidence-Based Medicine Committee reported an evidence-based review of treatments for essential tremor [13] and rated all studies to be classified as having Level-I of clinical evidence for study quality using a previously reported checklist of methodological items [14], which was also applied for the current review.

Fig. (1).

PRISMA Flowchart for the study on pharmacological therapies in essential tremor. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

2. Beta-adrenergic blockers

Beta-adrenergic blockers, also known as beta-blockers, β-adrenergic antagonists, β-adrenergic receptor antagonists or β-adrenergic blocking agents, act by blocking the action of the endogenous catecholamines noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and adrenaline (epinephrine) on the β-adrenergic receptors (these are G protein-coupled receptors). There are 3 major types of beta-adrenergic receptors, that are designated as β1, β2, and β3 (despite β4 receptor that has been described as well, it is considered as a novel state of the β1-adrenergic receptor) [15]. Table 1 summarizes the mechanisms of action of the β-adrenergic blockers that have been used in drug trials for ET.

Table 1.

Mechanisms of action of β-blockers used in published drug-trials for ET.

| 1. Non-selective β-blockers 1.1 Propranolol. 1.2 Timolol. 1.3 Nadolol. 1.4 Sotalol. 1.5 Pindolol. 2. Selective β1-adrenergic receptors blockers 2.1 Metoprolol. 2.2 Atenolol. 3. Mixed β1-adrenergic antagonist and β2-adrenergic 3.1 Indenolol. 4. Mixed alpha and β-blockers 4.1 Arotinolol (partial β3 agonist). 4.2 Nipradilol (non-selective β-blocker). |

2.1. Propranolol

As was previously commented, propranolol (1-naphthalen-1-yloxy-3-(propan-2-ylamino)propan-2-ol) is one of the drugs of choice for the therapy of ET. Propranolol is able to markedly decrease the amplitude of a tremor [16-34], despite the lack of correlation between blood propranolol levels and the efficacy of suppression of tremor [25-30, 33]. The efficacy of controlled-release preparations of propranolol has been reported to be similar to that of standard-release ones [35-37]. Propranolol has a slight or no effect on head tremors [38-40]. A total of 13 reports showed a quality rate >50% [16, 17, 19, 21, 23, 24, 26, 30, 31, 35, 36, 38, 39]. It is not well known whether the mechanism of action of this drug against tremor is peripheral or central [41], although a recent study using positron emission tomography (PET) with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) has shown a decreased glucose metabolism in the basal ganglia in ET patients with good therapeutic response to propranolol compared with those with bad response [42]. Effective doses, side effects, and contraindications for the use of propranolol are summarized in Table 2. Propranolol is considered as an effective treatment for ET affecting upper limbs according to the evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of ET from the American Academy of Neurology [43], the Italian Movement Disorders Association [44], and by the MDS Task Force on Tremor [13], and is considered as probably effective for head tremors [38].

Table 2.

Beta-adrenergic blockers used in the treatment of essential tremor.

| Drug | Recommended Doses (mg/day) | Main Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Propranolol Metoprolol Atenolol Timolol Nadolol Sotalol Indenolol Arotinolol |

120-320 100-200 100 10 120-240 160 40-80 10-30 |

Common side effects: hypotension; slow heartbeat; dizziness; blurred vision; excessive tiredness; cold hands and feet; diarrhea and nausea. Less common side effects: loss of libido; erectile dysfunction or impotence in men insomnia; depression. Contraindications: asthma; congestive heart failure; 2nd or 3rd-degree heart block; bradycardia; diabetes mellitus in patients prone to hypoglycemia awareness; peripheral vascular disease. |

2.2. Other Beta-blockers

Other beta-adrenergic blockers, including metoprolol (1-[4-(2-methoxyethyl)phenoxy]-3-(propan-2-ylamino)propan-2-ol) [45-54], atenolol (2-[4-[2-hydroxy-3-(propan-2-ylamino)propoxy]phenyl]acetamide) [53, 55, 56], nadolol ((2~{R},3~{S})-5-[3-(~{tert}-butylamino)-2-hydroxypropoxy]-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene-2,3-diol) [57], indenolol (1-(1~{H}-inden-4-yloxy)-3-(propan-2-ylamino)propan-2-ol) [58], sotalol (~{N}-[4-[1-hydroxy-2-(propan-2-ylamino)ethyl]phenyl]methanesulfonamide) [52], and timolol ((2~{S})-1-(~{tert}-butylamino)-3-[(4-morpholin-4-yl-1,2,5-thiadiazol-3-yl)oxy]propan-2-ol) [55], have shown certain degree of efficacy in the treatment of ET, although this was always lesser than that of propranolol [45-58], while arotinolol (5-[2-[3-(~{tert}-butylamino)-2-hydroxypropyl]sulfanyl-1,3-thiazol-4-yl]thiophene-2-carboxamide) showed similar efficacy than propranolol in one study [59], and lesser efficacy in another [60]. Contrary to that described with propranolol, plasma levels of metroprolol (and its metabolite alpha-hydroxymetoprolol) are related with the improvement of ET with this drug [54]. Nipradilol ([8-[2-hydroxy-3-(propan-2-ylamino)propoxy]-3,4-dihydro-2~{H}-chromen-3-yl] nitrate) did not improve [61], and pindolol (1-(1~{H}-indol-4-yloxy)-3-(propan-2-ylamino)propan-2-ol) worsened the tremor due to its action as a partial β-adrenergic agonist [26, 62]. Six reports on other beta-blockers than propranolol showed a quality rate >50% [49-53, 56]. Table 2 summarizes the recommended doses and side effects of beta-adrenergic blockers. According to the evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of ET from the American Academy of Neurology, atenolol and sotalol are probably effective, and nadolol is possibly effective in reducing ET affecting upper limbs [38], and the Italian Movement Disorders Association considers arotinolol and sotalol as second-line therapy [39]. The MDS Task Force on Tremor considered the evidence on the usefulness of nadolol, metoprolol, sotalol, and atenolol in the treatment of ET as insufficient [13].

Although it has been suggested that the reason why propranolol shows higher efficacy than other beta-blockers could be related to its high lipid solubility (by which it should reach the Central Nervous System better than other drugs with lower lipid solubility). Drugs with lower lipid solubility such as atenolol have certain degree of efficacy on ET [63], suggesting the possible role of a peripheral effect of these drugs.

3. Barbiturates

3.1. Primidone

Primidone (5-ethyl-5-phenyl-1,3-diazinane-4,6-dione) is a synthetic antiepileptic drug of the pyrimidinedione class. Both primidone, and its two active metabolites, phenobarbital (5-ethyl-5-phenyl-1,3-diazinane-2,4,6-trione) and PEMA (2-ethyl-2-phenylpropanediamide), are biologically active as anticonvulsants. The exact mechanism of action of primidone is not well known, but it is likely related to interactions with voltage-gated sodium channels which inhibit the high-frequency repetitive firing of action potentials. A recent study using 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy did not show significant differences in cerebellar dentate nuclei gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) concentrations between ET patients taking daily primidone and those not treated with primidone [64].

Many reports have shown the efficacy of primidone in the therapy of ET [65-70], which was found to be similar to that of propranolol in comparative studies between these two drugs [71-73]. Primidone has shown improvement of essential vocal tremor in 14 out of 26 patients [74]. It has been described that the efficacy of primidone is maintained at least 1 year after starting the therapy [75], despite some reports have described tolerance [76]. Phenobarbital and PEMA, the main metabolites of primidone, showed a lesser efficacy for the reduction of tremor than that of primidone [77-79], suggesting that the efficacy of primidone is not completely due to these metabolites. Phenobarbital has shown higher efficacy than placebo in the control of ET [80, 81].

Table 3 summarizes the recommended doses and adverse effects of primidone and phenobarbital. Primidone is considered as an effective drug in the treatment of ET affecting upper limbs according to the evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of ET from the American Academy of Neurology [43] and the MDS Task Force on Tremor [13], and as a first-line therapy according to the Italian Movement Disorders Association [44]. It is usual in the clinical practice to start the therapy with the low-dose of primidone (32.25-62.5 mg per day), in an attempt to avoid the initial intolerance symptoms (nausea, vomiting, excessive sedation). A double-blind placebo-controlled study with a follow-up period of 1 year showed similar efficacy of doses of 250 mg per day and 750 mg per day, but the frequency of side effects was higher in the group treated with higher doses [82]. However, another study comparing initial doses of 2.5 mg with 25 mg per day showed similar tolerance between the two groups, thus suggesting that acute intolerance symptoms should be an idiosyncratic effect [83]. Eight studies related with primidone [67, 68,71, 77-79, 82, 83], and two with phenobarbital [80,81] showed quality rates higher than 50% [67, 68, 71, 77-83]. Discontinuation of primidone therapy at a low dose because of side effects was reported in 48% of patients, this event was unrelated to the main polymorphisms in the CYP2C19 and CYP2C9/8 genes [84, 85].

Table 3.

Antiepileptic drugs used in the treatment of essential tremor

| Drug | Recommended Doses (mg/day) | Main Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Barbiturates Primidone Phenobarbital |

37.5-750 50-200 |

Common side effects: dizziness; drowsiness; lightheadedness; loss of coordination; anorexia; nausea; vomiting. Severe but less common side effects: Severe allergic reactions including angioedema; diplopia or unusual eye movements; decreased sexual ability; fever; measles-like rash; new or worsening previous mental or mood changes (eg; anxiety; depression; restlessness; irritability; panic attacks; behavior changes; suicidal thoughts or attempts); new or worsening previous seizures; excessive tiredness or weakness sensation |

| Topiramate | 50-200 | Cognitive and psychiatric alterations; visual disturbances; nervousness; weight loss; anhydrosis; glaucoma; tremor; nephrolithiasis; |

| Gabapentin | 300-2400 | Drowsiness; weight gain; tremor; diplopia; dizziness; gastric discomfort. |

| Levetirazetam | 500-2000 | Drowsiness; asthenia; dizziness; headache; ataxia; insomnia; nervousness; tremor; vertigo; diplopia; gastrointestinal complaints; cytopenia. |

| Zonisamide | 100-200 | Anorexia; irritability; confusion; depression; diplopia; hypersensitivity; nausea; abdominal pain; diarrhea; exanthematic reactions; fever; weight loss |

| Pregabaline | 150-600 | Dizziness; drowsiness. |

| Lacosamide | 100-400 | Blurred vision or diplopia; dizziness; drowsiness; headache; diarrhea; mild itching; pain; nausea; vomiting; tiredness or sensation of weakness. |

| Perampanel | 4 | Dizziness, somnolence, vertigo, ataxia, slurred speech, blurred vision, irritability, mood changes, psychosis (acute psychosis, hallucinations, delusions, paranoia) and delirium |

3.2. Phenobarbital

Phenobarbital, a barbiturate with anticonvulsant, sedative and hypnotic properties, acts primarily on GABAA receptors, increasing the flow of chloride ions into the neurons and decreasing the excitability by hyperpolarization of the postsynaptic membranes. It also has a blocking action of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors and inhibits glutamate release through P/Q-type high-voltage activated calcium channels. As it was previously commented, phenobarbital has shown higher efficacy than placebo in improving ET [80, 81]. The MDS Task Force on Tremor considered that there is insufficient evidence on the efficacy of this drug in the treatment of ET [13].

3.3. T2000

The main metabolite of the barbiturate T2000 (1,3-Dimethoxymethyl-5,5-diphenylbarbituric acid), and diphenyl barbituric acid has anticonvulsant activity and shows similar enhancement of GABA-evoke chloride currents. The efficacy of T2000 at 800 mg per day compared with 600 mg per day was shown in 2 brief randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, double-blinded, single-center trials involving, respectively, 12 and 22 young patients with ET [86]. However, other recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre trials involving older patients with ET showed a lack of significant improvement in tremor and a high frequency of adverse events leading to drug withdrawal, using doses from 600 up to 1000 mg per day [87]. Although both the articles had a quality score higher than 50%, the MDS Task Force on Tremor considered that there is insufficient evidence of the efficacy of this drug for the treatment of ET [13].

4. Other antiepileptic drugs

4.1. Gabapentin and Tiagabine

The antiepileptic gabapentin (2-[1-(aminomethyl)cyclohexyl]acetic acid) was synthesized in an attempt to mimic the chemical structure GABA. However, it seems unlikely that this drug should act on the same brain receptors that GABA, and it is thought that it binds to the α2δ subunits of voltage-gated calcium N-type channels, reducing calcium currents after chronic application. Although several preliminary reports, including open-label studies and double-blind placebo-controlled studies [88-90] showed efficacy in the treatment of ET affecting upper limbs, with similar efficacy to propranolol [89], another double-blind placebo-controlled study did not confirm this efficacy [91]. Two studies showed quality rates higher than 50% [89, 91]. Recommended doses are summarized in Table 3. Gabapentin is recommended as second-line therapy in the treatment of ET according to the Italian Movement Disorders Association [44], while it is considered as probably effective in reducing upper limbs tremor according to the evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of ET from the American Academy of Neurology [43], and with insufficient evidence of efficacy by the MDS Task Force on Tremor [13].

An anecdotal report described improvement of voice with gabapentin [92], and an open-label study showed a lack of efficacy of tiagabine ((3~{R})-1-[4,4-bis(3-methylthiophen-2-yl)but-3-enyl]piperidine-3-carboxylic acid), which acts through blockade of the GABA transporter 1 (enhancing GABA concentrations) in the treatment of ET [93].

4.2. Topiramate

Topiramate ([(1~{R},2~{S},6~{S},9~{R})-4,4,11,11-tetramethyl-3,5,7,10,12-pentaoxatricyclo[7.3.0.0^{2,6}]dodecan-6-yl]methyl sulfamate) is a sulfamate-substituted monosaccharide related to fructose. Its mechanism of action is not well-known but includes a blockage of voltage-dependent sodium channels, inhibition of high-voltage-activated calcium channels, an increase of GABA activity at some subtypes of the GABAA receptors, antagonism of AMPA/kainate subtype of the glutamate receptor, and inhibition of the carbonic anhydrase enzyme (particularly isozymes II-cytosolic- and IV-membrane associated).

Improvement of ET with topiramate has been suggested by several anecdotal reports [94, 95], and was confirmed by some double-blind placebo-controlled trials [96-98] but not by others [99]. The efficacy of topiramate was found to be similar to that of propranolol in a comparative study [100]. Four of these studies showed a quality rate higher than 50% [96-99]. Topiramate was considered as probably effective in the treatment of ET affecting upper limbs according to the evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of ET from the American Academy of Neurology [43], recommended as first-line therapy by the Italian Movement Disorders Association [44], and considered efficacious by the MDS Task Force on Tremor [13]. Despite a meta-analysis of previous studies showed higher efficacy of topiramate than placebo in the treatment of ET [101], a recent systematic review including three trials comparing topiramate with placebo showed limited data and very low to low-quality evidence to support the efficacy of this drug [102].

Table 3 summarizes the recommended doses and the main side-effects of topiramate. Treatment with topiramate can cause psychosis [103] and tremor as side effects [104] in some cases.

4.3. Levetiracetam

Levetiracetam ((2~{S})-2-(2-oxopyrrolidin-1-yl)butanamide) is the S-enantiomer of etiracetam, which is structurally similar to piracetam (2-(2-oxopyrrolidin-1-yl)acetamide, a prototypical nootropic drug). Levetiracetam binds to a synaptic vesicle glycoprotein (SV2A), which seems to be involved in vesicle fusion in neurotransmitter exocytosis. It also takes part in the negative modulation of GABA associated with Zn2+, in the inhibition of presynaptic Ca2+ voltage-dependent type N, and in GABA release.

A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized crossover study [105], a double-blind placebo-controlled study on the acute effects of levetiracetam [106], and an open-label study [107] showed efficacy of levetiracetam in the treatment of ET affecting upper limbs (in the latter, the efficacy was similar to that of primidone and propranolol) [107]. However, other studies did not show beneficial effects [108-110], and many patients withdrew the treatment because of side effects in one of them [109]. Three of these studies showed quality rates higher than 50% [105, 106, 110]. Table 3 summarizes the recommended doses and the main side-effects of levetiracetam. The evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of ET from the American Academy of Neurology suggested that levetiracetam does not reduce limb tremor and ET, and therefore, it should not be considered as a useful treatment [43]. The MDS Task Force on Tremor considered levetiracetam as non-efficacious in the treatment of ET [13].

4.4. Zonisamide

Zonisamide (1,2-benzoxazol-3-ylmethanesulfonamide) is a sulfonamide with antiepileptic action. The mechanism of action of zonisamide is not well understood, although it has been proposed to be related to a blocking action of voltage-gated sodium channels and T-type calcium channels, inhibition of carbonic anhydrase, and modulation of GABAergic (it binds allosterically to GABA receptors and inhibits GABA reuptake) and glutamatergic neurotransmission (by enhancing the uptake of glutamate). Zonisamide significantly improved tremor in two animal models of ET: harmaline-induced tremor and in the GABAA receptor α1 subunit-null mouse models [111].

Several studies have shown some degree of clinical improvement [112-115], improvement in accelerometry tests without clinical improvement [116], or lack of improvement [117] of ET affecting upper limbs with zonisamide. Zonisamide showed higher efficacy than propranolol in a pilot study involving patients with isolated ET head tremor [118]. Only one of these studies showed a quality rate higher than 50% [114]. Recommended doses and side effects of zonisamide are summarized in Table 3. It is of note that some patients can develop mania with this drug [119].

Zonisamide was recommended as second-line therapy by the Italian Movement Disorders Association [44]. In contrast, the evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of ET by the American Academy of Neurology [43], the MDS Task Force on Tremor [13], and a recent systematic review of the literature [120] suggested that there is insufficient evidence to support or to refute the use of this drug in the treatment of ET.

4.5. Pregabalin

Pregabalin ((3~{S})-3-(aminomethyl)-5-methylhexanoic acid) is a GABA analogue, although it does not convert into GABA, does not bind to GABA receptors, and does not modulate GABA transport or metabolism. However, it can increase GABA levels in the brain by increasing the expression of the synthesizing enzyme of GABA, L-glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD). Pregabalin is a ligand of (and acts as) an inhibitor of the α2δ subunit site of certain voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels.

Several preliminary studies showed improvement of ET with pregabalin [121, 122], but further studies showed lack of improvement [123, 124], and even worsening of quality of life rating scale [123]. Three of these studies showed quality rates higher than 50% [142-144]. Table 3 summarizes the recommended doses and the main side-effects of pregabalin. According to the evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of ET by the American Academy of Neurology, there is insufficient evidence to support or to refute the use of this drug in the treatment of ET [44], and the MDS Task Force on Tremor considered it as non-efficacious in the treatment of ET [13].

4.6. Lacosamide

Lacosamide (2~{R})-2-acetamido-~{N}-benzyl-3-methoxypropanamide), is an antiepileptic drug which seems to act by enhancing the slow inactivation of voltage-gated sodium channels without affecting the fast inactivation of voltage-gated sodium channels, and by the modulation of the collapsin response mediator protein 2 (CRMP-2), preventing the formation of abnormal neuronal connections in the brain. Despite a dose-dependent improvement in harmaline-induced tremor in rats treated with lacosamide [125], with a similar or superior effect to that of propranolol and primidone, a lack of improvement in tremor in human ET patients treated with this drug was observed in an open-label study (quality rate lesser than 50%) [126].

4.7. Ethosuximide

Ethosuximide (3-ethyl-3-methylpyrrolidine-2,5-dione) belongs to the succinimide family and is used to treat absence seizures. Its mechanisms of actions include the blockade of T-type calcium channels and possible effects on other classes of ion channels. Although ethosuximide significantly improves tremor in the harmaline-induced tremor and in the GABAA receptor α1 subunit-null mice [111], it showed a lack of efficacy in the treatment of patients with ET in an open-label study (quality rate lesser than 50%) [127].

4.8. Perampanel

Perampanel (2-(2-oxo-1-phenyl-5-pyridin-2-ylpyridin-3-yl)benzonitrile) is a bipyridine derivative that acts as a selective non-competitive antagonist of the AMPA glutamatergic receptors. A recent open-label study involving 12 ET patients with upper limb tremor with 4 mg per day of perampanel has shown a significant improvement in tremor in 8 patients who completed the study (quality rate lesser than 50%) [128].

4.9. Other Antiepileptic Drugs

An anecdotal report described an improvement in ET with oxcarbazepine (5-oxo-6~{H}-benzo[b][1]benzazepine-11-carboxamide) [129], while carisbamate ([(2~{S})-2-(2-chlorophenyl)-2-hydroxyethyl] carbamate) showed lack of efficacy in the treatment of ET in a multicentre double-blind placebo-controlled study (quality rate higher than 50%) [130].

5. Calcium channel blockers

Calcium channel blockers can modify tremor amplitude in patients with ET, as was firstly demonstrated by Topaktas et al. [131], who reported increased severity of postural tremor induced by a single dose of the dihydropirydine nifedipine (dimethyl 2,6-dimethyl-4-(2-nitrophenyl)-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate) in an open-label study (quality rate lesser than 50%).

While flunarizine (1-[bis(4-fluorophenyl)methyl]-4-[(~{E})-3-phenylprop-2-enyl]piperazine, a piperazine derivative which acts as a selective calcium entry blocker with calmodulin binding properties, and shows histamine H1 blocking activity) showed a beneficial short-term effect on ET in a double-blind placebo-controlled study with a quality rate higher than 50% [132], its long-term use caused, as it was expected [133-135], important side-effects in a high percentage (29.4%) of ET patients such as parkinsonism, dystonia, weight gain and depression [136]. Moreover, an investigator-blinded trial (quality rate lesser than 50%) showed a lack of efficacy [137]. According to the evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of ET by the American Academy of Neurology, flunarizine possibly has no effect on treating upper limb tremor and may not be considered as a good choice of drug [43]. Moreover, the MDS Task Force on Tremor considered that there is insufficient evidence on the efficacy of flunarizine in the treatment of ET [13].

Acute administration of nicardipine (5-~{O}-[2-[benzyl(methyl)amino]ethyl] 3-~{O}-methyl 2,6-dimethyl-4-(3-nitrophenyl)-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate) showed a higher efficacy than that of placebo in decreasing tremor amplitude [138], and this drug showed a similar short-term efficacy than propranolol [139], although this effect is not maintained after a long-term follow-up period [138] in two open-label studies with a quality rate lesser than 50% [138, 139]. Nimodipine (3-~{O}-(2-methoxyethyl) 5-~{O}-propan-2-yl 2,6-dimethyl-4-(3-nitrophenyl)-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate) showed short-term efficacy in improving ET as well in a double-blind placebo study with a quality rate higher than 50% [140] and was considered as possibly effective by the evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of ET from the American Academy of Neurology

[43]. However, evidence was insufficient on the efficacy according to the MDS Task Force on Tremor [13]. Nifedipine, nicardipine, and nimodipine are dihydropyridine derivatives that act as L-type calcium-channel-blockers. Recommended doses of calcium-channel blockers are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Calcium-channel blockers tested in the treatment of essential tremor.

| Drug | Recommended Doses (mg/day) | Main Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Flunarizine | 10-20 | Dizziness; nausea; constipation; facial flushing; oedema; headache; drowsiness; weight gain; parkinsonism; tardive dyskinesia; dystonia; depression. |

| Nicardipine | 40-120 | Dizziness; nausea; constipation; facial flushing; oedema; headache; low blood pressure; fatigue; palpitations; nausea; sore throat. |

| Nimodipine | 60-240 | Dizziness; nausea; constipation; facial flushing; oedema; headache; low blood pressure; fatigue; palpitations; nausea; sore throat. |

Several T-type calcium channel antagonists such as ethosuximide (3-ethyl-3-methylpyrrolidine-2,5-dione), a mibefradil derivative, and 4-dihydroquinazoline (1,4-dihydroquinazoline) have shown improvement in tremor in two mouse models of ET [110, 141]. A new double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving a significant number of patients with ET inadequately treated with existing therapies using a selective modulator of the T-type calcium channel (CX-8998), is currently undergoing [142].

6. Benzodiazepines

6.1. Alprazolam

Alprazolam (8-chloro-1-methyl-6-phenyl-4~{H}-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a][1,4]benzodiazepine) is a triazole-benzodiazepine which acts through the activation of the GABAA receptors. A double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel study involving 24 ET patients showed an improvement in tremor affecting upper limbs in patients treated with alprazolam [143]. A double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled study involving 22 ET patients showed that alprazolam was superior to placebo and equipotent to primidone in the treatment of tremor affecting upper limbs [144]. These two studies showed a quality rate higher than 50% [143, 144]. A single dose of alprazolam showed a significant attenuation of hand tremor, decreased cortical activity in the tremor frequency range, and increased contralateral cortical beta activity reduction in ET patients, which are correlated to reduction in tremor with the increased ratio of cortical beta activity [145].

The Italian Movement Disorders Association recommended alprazolam as second-line therapy [44], and the MDS Task Force on Tremor considered this drug as efficacious [13]. In contrast, the evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of ET by the American Academy of Neurology [43], and a systematic review of the literature [146] concluded that the evidence is not sufficient to support or refute the use of alprazolam in the treatment of ET. Recommended doses of alprazolam blockers are given in Table 5.

Table 5.

Other drugs tested in the treatment of essential tremor.

| Drug | Recommended Doses (mg/day) | Main Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Olanzapine | 2.5-10 |

Common side effects: insomnia; anxiety; headache. Severe but less common side effects: sedation; somnolence; dizziness; weight gain; gynecomastia; hyperprolactinemia with amenorrhea and galactorrhea; movement disorders (dystonic reactions; parkinsonism; akathisia; tardive dyskinesia); orthostatic hypotension; oedema. |

| Clozapine | 12.5-75 |

Common side effects: constipation; dizziness; drowsiness; headache; dry mouth or increased sweating or saliva production; lightheadedness when standing up; nausea; heartburn; strange dreams and other trouble sleeping; weight gain. Severe but less common side effects: Severe allergic reactions; agitation; chest pain; confusion-delirium; seizures; severe headache; dizziness; or vomiting; vision changes; pancytopenia. |

| Alprazolam Clonazepam |

0.75 0.25-5 |

Common side effects: sedation; dizziness; ataxia; depression; confusion and hallucinations in elder people. Contraindications: allergy to benzodiazepines; asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. narrow angle glaucoma; liver disease; |

| Methazolamide Acetazolamide |

100-200 250-750 |

Side effects: blurred vision; changes in taste; constipation; diarrhea; drowsiness; frequent urination; loss of appetite; nausea; vomiting; cramps; hearing problems; tinnitus; allergy and photosensitivity. Contraindications: hyponatremia; hypokalemia; kidney; liver; or adrenal gland disease; closure-angle glaucoma. |

6.2. Clonazepam

Clonazepam (5-(2-chlorophenyl)-7-nitro-1,3-dihydro-1,4-benzodiazepin-2-one) is a benzodiazepine with antiepileptic properties, which acts by enhancement of the neurotransmitter GABA via modulation of the GABAA receptor. Clonazepam showed efficacy in the treatment of ET in an open-label study (quality rate lesser than 50%) [147] but not in a double-blind placebo-controlled one with a quality rate higher than 50%) [148]. This drug has been considered by the evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of ET from the American Academy of Neurology as possibly effective [43]. Recommended doses of clonazepam blockers are given in Table 5.

6.3. Gap-junctions Inhibitors

Several drugs acting as broad spectrum gap-junction inhibitors such as heptanol (heptan-1-ol), octanol (octan-1-ol), octanoid acid, carbenoxolone ((2~{S},4~{a}~{S},6~{a}~{R},6~{a}~{S},6~{b}~{R},8~{a}~{R},10~{S},12~{a}~{S},14~{b}~{R})-10-(3-carboxypropanoyloxy)-2,4~{a},6~{a},6~{b},9,9,12~{a}-heptamethyl-13-oxo-3,4,5,6,6~{a},7,8,8~{a},10,11,12,14~{b}-dodecahydro-1~{H}-picene-2-carboxylic acid) and blocking gap-junctions containing connexin 36 (mefloquine, (~{S})-[2,8-bis(trifluoromethyl)quinolin-4-yl]-[(2~{R})-piperidin-2-yl]methanol), have shown efficacy in decreasing harmalin-induced tremor in rodents [149, 150].

Octanol has shown efficacy, without relevant side effects, in the treatment of ET patients in an open-label [151] and in a double-blind study [152]. Acute administration of octanoic acid (the primary metabolite of 1-octanol) has shown a significant dose-dependent improvement of upper limb tremor in ET patients, both in an open-label, single-ascending 3 + 3 dose-escalation designed study [153] and in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover, phase I/II clinical trial [154]. In addition, a recent prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study has shown improvement in essential voice tremor with octanoic acid [154]. Three of these studies showed a quality rate higher than 50% [152, 154, 155]. In contrast, low-dose mefloquine did not prove beneficial in the treatment of ET in an open-label study involving 4 patients (quality rate lower than 50%) [149].

7. Neuroleptic drugs

Yetimalar et al., described an improvement of tremor in some ET patients treated with olanzapine (2-methyl-4-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-10~{H}-thieno[2,3-b][1,5]benzodiazepine) [156], and a similar efficacy of 20 mg per day of olanzapine than 120 mg per day of propranolol in a randomized open-label crossover study involving 38 ET patients [157], showing in both studies a quality rate lesser than 50%. Moreover, it should be taken into account that the use of this drug in the long-term treatment for ET could result in an increased risk of developing parkinsonism [158]. An improvement in tremor in some patients treated with clozapine (3-chloro-6-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-11~{H}-benzo[b][1,4]benzodiazepine) [159, 160] was observed and a randomized, double-blind, crossover study with a quality rate higher than 50%, involving 15 drug-resistant patients with ET has also shown a significant improvement of tremor with this drug [161]. An open-label study using quetiapine (2-[2-(4-benzo[b][1,4]benzothiazepin-6-ylpiperazin-1-yl)ethoxy]ethanol) up to 75 mg per day in 10 ET patients showed improvement of upper limbs tremor in 3 of them (a quality rate lesser than 50%) [162].

Based on the evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of ET from the American Academy of Neurology [43], and with the MDS Task Force on Tremor [13], there is insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of clozapine in the treatment of ET, while both olanzapine and clozapine are considered as second-line treatment for ET according to the recommendations of the Italian Movement Disorders Association [44]. Recommended doses of olanzapine and clozapine are given in Table 5.

8. Antiparkinsonian drugs

Several reports with a quality rate lesser than 50% described an improvement of ET with amantadine (adamantane-1-amine) [163-165]. However, a double-blind placebo-controlled study (quality rate higher than 50%) showed a lack of efficacy of this drug in the treatment of ET, and even worsening of postural tremor in 37.5% of patients [166]. The MDS Task Force on Tremor considered that there is insufficient evidence to support or refuse the use of amantadine in ET [13].

One short-term pilot study with a quality rate lesser than 50% suggested a beneficial effect of the dopamine D2/D3 agonist pramipexole ((6~{S})-6-~{N}-propyl-4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-1,3-benzothiazole-2,6-diamine) in improving upper limb tremor in patients with ET [167]. This drug, used at low doses (but not at high doses), had a beneficial effect on the harmaline-induced model of ET in rodents as well [168].

9. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors

The results of studies using methazolamide (~{N}-(3-methyl-5-sulfamoyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-ylidene)acetamide) or acetazolamide (~{N}-(5-sulfamoyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)acetamide) have shown efficacy in the treatment ET affecting upper limbs in several studies [169, 170] but not in others [144, 171]. Head tremor [172] and voice tremor [169, 172] did not improve with methazolamide. Two of these studies showed a quality rate higher than 50% [144, 171]. The MDS Task Force on Tremor considered that there is insufficient evidence to support or refuse the use of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors in ET [13]. Recommended doses of methazolamide and acetazolamide are given in Table 5.

10. Botulinum toxin type A

The proposed mechanism of action of botulinum toxin in ET is the restoration of the presynaptic inhibition of afferent fibers type Ia [173]. Injection of selected forearm flexor and extensor muscles with botulinum toxin type A (BTX A) improved upper limb tremor in many ET patients, with a low frequency of side effects, mainly transient weakness, according to several studies with different designs which are summarized in Table 6 [174-185]. Several studies, summarized in Table 6, have shown good therapeutic effects on essential head tremor (EHT) [186, 187] and essential voice tremor (EVT) [188-193]. In addition, a limited number of patients with possibly related conditions such as chin tremor [194, 195], jaw tremor [196] and essential palatal tremor [197, 198], have shown improvement with BTX A infiltrations. Three reports regarding ET involving upper limbs [176, 179, 183] and one regarding EHT [186] showed quality rates higher than 50%.

Table 6.

Studies with botulinum toxin A (BTX A) for the treatment of severe ET.

| Tremor Location | Author; Year [Ref] | Study Design | Main Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPPER LIMBS | Trosch & Pullman, 1994 [174] | Open-label study involving 12 ET patients. Identification of target muscles by clinical evaluation and tremor analysis including EMG activity. Infiltration of 10-25 Units of BTX A in ECU; ECR; FCR and FCU in all patients; and 75 Units in biceps and triceps and 20 Units in FDD in some patients). Evaluation at 6-weeks. | Five patients reported subjective moderate to marked improvement; only 3 showed an objective major reduction in tremor amplitude, and tremor severity scales showed mild but statistically significant improvement. | |

| Henderson et al., 1996 [175] | Single-blind placebo-controlled study with placebo given first. Infiltration of 25 Units ob BTX A divided into several muscles including EIP and FDP. Only 3 of the 17 patients involved were diagnosed with “pure” ET | Improvement of postural tremor in the pool of patients included with “pure ET” or ET associated with other conditions was twice with BTX A than with placebo | ||

| Jankovic et al., 1996 [176] | Randomized-double blind; placebo-controlled study. Infiltration of 15 Units of BTX A or placebo in FCU and FCR and 10 in ECR brevis and ECR longus and in ECU in the dominant hand. A second injection of 30 Units in FCU and FCU and 20 in ECR and ECU was administered at 4-weeks if there was no improvement. The final evaluation was done at 16 weeks. | Mild to moderate subjective improvement of tremor in 75% of patients treated with BTX A and 27% with placebo. A non-significant trend towards improvement in tremor scales. Reduction in tremor amplitude (postural accelerometry) in 75% of BTX A-treated patients vs 8.3% of placebo-treated. Mild finger weakness in all BTX A treated patients | ||

| Pullman et al., 1996 [177] | Open-label prospective study involving 187 patients with several limb disorders (14 with essential tremor) during an 8-year period | 25% reduction in tremor amplitude. Mild transient weakness as a frequent side effect | ||

| Pacchetti et al., 2000 [178] | Open-label study involving 20 ET patients. Recording of activity in ECR; ECU; FCR; FCU; brachioradialis; PT; biceps and triceps of the right arm and infiltration of BTX A in muscles showing tremor at 2 postures avoiding ECR or ECU if possible. Measurement of tremor amplitude with accelerometry. | Significant reduction in severity and functional rating scales scores and of tremor amplitude as measured with accelerometry and EMG. Mild transient 3rd finger weakness in 15% of patients. | ||

| Brin et al., 2001 [179] | Randomized; multicenter; double-masked clinical trial with three treatment groups: low-dose botulinum toxin type A (50 U); high dose BTX A (100 U); and vehicle placebo involving 133 patients with ET; injected into the wrist flexors and extensors. Follow-up for 16; Assessment with clinical rating scales; measures of motor tasks and functional disability; and global assessment of treatment. | Significant improvement of postural but not of kinetic tremor. Lack of improvement in the measures of motor tasks and functional disability. Dose-dependent hand weakness as the main side effect. | ||

| Samotus et al., 2016 [180] | 38-week open-label study involving 24 ET patients injected with incobotulinumtoxinA using guiding muscle selection. Assessment with clinical scales of severity and quality of life, and objective kinematic assessments | Significant improvement of tremor severity and quality of life in clinical scales; and a significant reduction in tremor amplitude in the wrist and shoulder joints. Mild weakness in injected muscles without interference in arm function in 40% of patients | ||

| Samotus et al., 2017 [181] | 96-week open-label study involving 24 ET patients injected with incobotulinumtoxinA using guiding muscle selection. Assessment with clinical scales of severity and quality of life, and objective kinematic assessments | Significant improvement of tremor severity and quality of life in clinical scales; and a significant reduction in tremor amplitude in the wrist and shoulder joints. Mild weakness in injected muscles without interference in arm function in 40% of patients | ||

| Samotus et al., 2018 [182] | 96-week open-label study involving 10 ET patients (drug naïve for incobotulinumtoxin A and oral drugs) injected with incobotulinumtoxinA using guiding muscle selection. Assessment with clinical scales of severity and quality of life, and objective kinematic assessments | Significant improvement of tremor severity and quality of life in clinical scales; and a significant reduction in tremor amplitude in the wrist and shoulder joints. 44.6% (p <0.0005) non-dose-dependent reduction in maximal grip strength; but only 2 participants complained of mild weakness | ||

| Tremor Location | Author; Year [Ref] | Study Design | Main Results | |

| Mittal et al., 2018 [183] | 28-week; double-blind; placebo-controlled; crossover trial involving 33 ET patients injected with 80–120 units of IncoA into 8–14 hand and forearm muscles using a customized approach and selection by needle EMG. Assessment with clinical scales of tremor and measurement of muscle strength by an ergometer | Significantly higher improvement in clinical tremor scales and subjective improvement for IncoA than for placebo. Non-significant differences in developing mild transient hand weakness between the two groups | ||

| Niemann & Jankovic, 2018 [184] | Retrospective review of a database of patients treated with onaBoNT-A for hand tremor evaluated between 2010 and 2018 in at least 2 sessions with follow-up (53 of them diagnosed with ET; most of them injected in FCR and FCU). | 80.2%-85.7% reported moderate or marked improvement at their first and last follow-up visit; respectively. Total dose injected increased significantly between the first and the last visit. Only 12.2% developed transient weakness of pain | ||

| Samotus et al., 2019 [185] | 30-weeks open-label study; with follow-ups six-weeks post-treatment; involving 31 ET participants who received three bilateral-arm BoNT-A injection cycles. Assessment with clinical scales of severity and quality of life, and objective kinematic assessments | Significant improvement of tremor severity and quality of life in clinical scales; and a significant reduction in tremor amplitude (47.7%) in both arms that persisted from weeks 18-30. Maximum grip strength reduced at week 6 (p = 0.001) but without functional impairment | ||

| HEAD | Pahwa et al., 1995 [186] | Double-blind; placebo-controlled study involving 10 patients with ET affecting the head. Infiltrations with 40 U of BTX A into each sternocleidomastoid muscle and 60 U into each splenius capitis using EMG guidance. Clinical and accelerometric evaluation at baseline; and at 2; 4; and 8 weeks after injection | Non-significant differences in subjective assessments; clinical ratings; and tremor amplitude between BTX A and placebo. Mild transient weakness in 70% of patients with BTX A and in 10% with placebo. | |

| Wissel et al., 1997 [187] | Open-label study of 43 patients with head tremor (29 with dystonic tremor and 14 with ET head tremor). Selection of muscles by EMG. Patients with ET head tremor received 400 U of BTX A (Dysport) divided into the two splenius capitis. | Significant improvement in tremor amplitude measured by accelerometry. mild and transient side effects (local pain; neck weakness; and dysphagia) reported by 40% | ||

| VOICE (EVT) | Warrick et al., 2000 [188] | Prospective open-label crossover study using BTX A involving 10 patients with EVT (bilateral 2.5-U or unilateral 15-U EMG-guided injection); followed by the alternative injection 16 to 18 weeks later. Evaluation with subjective judgment; and acoustic; aerodynamic; and nasopharyngoscopic data at 2; 6; 10; and 16 weeks after each injection. | Objective reduction in tremor severity in 3/10 patients with bilateral injection; and 2/9 with unilateral injection. Eight/10 wished to be re-injected at the conclusion of the study. Reduction in the vocal effort and in laryngeal airway resistance. Breathiness; coughing/choking and swallowing problems as side effects (one with pneumonia 2 to 4 weeks after unilateral injection). Side effects more severe with unilateral injection | |

| Hertegård S et al., 2000 [189] | Open-label study involving 15 patients with EVT. Injections of BTX A (1.25-2.5 U) to the thyroarytenoid muscles (in some cases cricothyroid or thyrohyoid muscles as well). Evaluations with subjective judgments by the patients; and perceptual and acoustic analysis of voice recordings. | Subjective beneficial effect in 67% of the patients. Significant decrease in voice tremor during connected speech (p <0.05); and in fundamental frequency during sustained vowel phonation (p <0.01); and nearly significant decrease in the fundamental frequency variations (p = 0.06). |

||

| Adler et al., 2004 [190] | Open-label randomized study involving 13 patients with EVT using 3 doses of BTX A (1.25 U; 2.5 U; or 3.75 U in each vocal cord). Evaluations at baseline and postinjection at weeks 2; 4; and 6. | Significant improvement with the 3 doses used in tremor severity scale scores; measures of functional disability; measures of the effect of injection; independent ratings of videotaped speech; and acoustic measures of tremor. Transient breathiness (11 patients) and dysphagia (3 patients) as the main adverse effects at all doses. | ||

| Justicz et al., 2016 [191] | Individual prospective cohort study involving 18 EVT patients. Assessments at baseline 2 weeks after propranolol therapy (maximum 60-90 mg/day) and 4 weeks after BTX A injection (average dose 3.18 UI in the thyroarytenoid/lateral cricoarytenoid complex; unilateral in 2 patients and bilateral in 16). | Both treatments get improvement in a Voice-Related Quality-Of-Life (VRQOL) questionnaire; in a Quality of life in Essential Tremor questionnaire; and in a blinded perceptual voice assessment; but only BTX A treatment showed significant changes with respect to baseline. | ||

| Tremor Location | Author; Year [Ref] | Study Design | Main Results | |

| Estes et al., 2018 [192] | Prospective crossover study involving 7 EVT patients injected with BTX A (15 U of Dysport in the left thyroaritenoid muscle) or a buffered hydrogel in laryngeal adductor muscles; with evaluation at 30 days after the procedure. Assessment with Vocal Tremor Scoring System (VTSS); and acoustic and aerodynamic measures. | Both treatments get improvement when compared with baseline, but there were non-significant differences between them. | ||

| Guglielmino et al., 2018 [193] | Randomized crossover study involving 5 EVT patients injected with BTX A (mean dose 1.26 U) or treated with oral propranolol 80 mg/day. Assessment with perceptual and acoustic measures before and after the administration of the two treatments. | Non-significant improvement of perceptual and acoustic measures; both with BTX A and propranolol. | ||

ECR: extensor carpi radialis; ECU: extensor carpi ulnaris; FCR: flexor carpi radialis; FCU: flexor carpi ulnaris; FDC: flexor digitorum comunis; PT pronator teres; EIP: extensor indicir proprius; FDP: flexor digitorum profundus; EMG electromyography; ET essential tremor; EVT: essential voice tremor.

Simpson et al., [199], in a review on the efficacy of BTX A analyzed with evidence-based medicine criteria, a level B of evidence for indication of BTX A in ET affecting upper limbs. BTX A is recommended for the treatment of refractory ET according to the recommendations of the Italian Movement Disorders Association [44]. The evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of ET from the American Academy of Neurology suggested that BTX A could be considered as possibly effective in reducing head and voice tremor [43]. Finally, the MDS Task Force on Tremor considered BTX A to be efficacious and possibly useful for ET affecting upper limbs, with hand weakness as a frequent dose-related adverse effect [13].

11. Other drugs tested in patients with ET

11.1. Drugs Acting on Adenosine Receptors

Recent data suggest a possible implication of adenosine A1 receptors in the pathogenesis of ET [4], such as the improvement of harmaline-induced tremor with selective adenosine A1 receptors [200]. In contrast, the non-selective adenosine A receptor inhibitor theophylline (1,3-dimethyl-7~{H}-purine-2,6-dione), which theoretically is supposed to worsen tremor, has shown improvement in ET, affecting upper limbs in a double-blind cross-over trial comparing doses of 150 mg per day with propranolol 80 mg per day and placebo (quality rate higher than 50%) [201]. Moreover, intravenous infusion of a single dose of 375 mg of aminophylline (1,3-dimethyl-7~{H}-purine-2,6-dione;ethane-1,2-diamine (theophylline/ethylendiamine in a 2:1 ratio) improved ET in 10 patients in a single-blind crossover study in comparison with placebo (a quality rate higher than 50%) [202]. The MDS Task Force on Tremor considered that there is insufficient evidence to support or refuse the use of theophylline in ET [13].

11.2. Drugs Acting on Glutamatergic Neurotransmission

Glutamatergic neurotransmission seems to play an important role in pathophysiology [4]. Harmaline-induced tremor improves with riluzole (6-(trifluoromethoxy)-1,3-benzothiazol-2-amine, which acts as a N-methyl-D-aspartate –NMDA- receptor blocker (decreasing glutamate release) [203], memantine (3,5-dimethyladamantan-1-amine, an NMDA receptor antagonist) [204], and berberine (16,17-dimethoxy-5,7-dioxa-13-azoniapentacyclo[11.8.0.0^{2,10}.0^{4,8}.0^{15,20}]henicosa-1(13),2,4(8),9,14,16,18,20-octane, an isoquinoline alkaloid that is found in several plants and acts by blockade of NMDA receptors, glutamate release, or both) [205]. However, memantine showed a lack of long-term improvement in upper limb tremors in an open treatment trial involving 16 ET patients (quality rate lesser than 50%) [206]. Data from studies on amantadine (which acts as an NMDA receptor antagonist) [163-166] and perampanel (which acts as AMPA receptor antagonist) [128] were commented on previously in other sections.

11.3. Drugs Acting on Serotoninergic Neurotransmission

An anecdotal report described improvement in ET with mirtazapine (5-methyl-2,5,19-triazatetracyclo[13.4.0.0^{2,7}.0^{8,13}]nonadeca-1(15),8,10,12,16,18-hexaene) [207] (agonist of the presynaptic alpha2-adrenergic, postsynaptic serotonergic 5-HT2 and 5-HT3, and histaminergic H1 receptors). However, a double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over study involving 17 patients, with a quality rate higher than 50%, failed to show the efficacy of this drug in the treatment of ET affecting upper limbs, and the profile of side-effects was bad [208], while an open-label study with observer-blinded (quality rate lesser than 50%), reported improvement [209].

Three initial reports with a quality rate lesser than 50% suggested the efficacy of trazodone (2-[3-[4-(3-chlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl]propyl]-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyridin-3-one), a phenylpiperazine derivative which acts as 5-HT2A receptor

antagonist, partial antagonist of 5-HT1A receptors, and an inhibitor of serotonin reuptake) in the treatment of ET [210-212], but this was not confirmed by 2 double-blind studies, both with quality rate higher than 50%, compared with placebo [213] or with propranolol and placebo [214]. The MDS Task Force on Tremor considered that there is insufficient evidence to support or refuse the use of mirtazapine in ET, and trazodone to be inefficacious [13].

Finally, the serotonin precursor tryptophan ((2~{S})-2-amino-3-(1~{H}-indol-3-yl)propanoic acid) was found ineffective in the treatment of ET in two studies with a quality rate lower than 50% [215, 216].

11.4. Drugs Acting on Alpha-adrenergic Receptors

Two open-label studies (with quality rate lesser than 50%) have shown improvement in ET affecting upper limbs with the alpha2-adrenergic agonist clonidine (~{N}-(2,6-dichlorophenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1~{H}-imidazol-2-amine) [217, 218], that was not confirmed by a double-blind study (with quality rate higher than 50%), which showed similar efficacy of clonidine to propranolol, although clonidine had more frequent side-effects [219]. In contrast, another double-blind study involving 10 patients (with a quality rate higher than 50%) did not show any improvement in ET with this drug [220].

Other studies showed an improvement in ET with the alpha1-adrenergic antagonist thymoxamine ([4-[2-(dimethylamino)ethoxy]-2-methyl-5-propan-2-ylphenyl] acetate) [221], and lack of improvement with the alpha1-adrenergic antagonist and partial 5-HT1A receptor agonist urapidil (6-[3-[4-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazin-1-yl]propyl-amino]-1,3-dimethylpyrimidine-2,4-dione) [213], and with the non-selective irreversible alpha-adrenergic antagonist phenoxybenzamide (2-phenoxybenzamide) [222]. Only one of these studies showed quality rate higher than 50% [213].

11.5. Miscellanea

Description of improvements in ET with other drugs such as sodium oxybate (sodium;4-hydroxybutanoate, a drug used in the treatment of cataplexy) [223, 224], glutethimide (3-ethyl-3-phenylpiperidine-2,6-dione) [225], topical anesthesia [226], bovine brain ganglioside [227], and high-dose thiamine (2-[3-[(4-amino-2-methylpyrimidin-5-yl)methyl]-4-methyl-1,3-thiazol-3-ium-5-yl]etanol) [228] has been given in anecdotal reports, all of them with a quality rate lesser than 50%.

In contrast, the GABA precursor progabide (4-[[(4-chlorophenyl)-(5-fluoro-2-hydroxyphenyl)methylidene]amino]butanamide) [229, 230], isoniazide (pyridine-4-carbo-hydrazide) [231], the alcohol methylpentinol (3-methylpent-1-yn-3-ol) [232], and the potassium channel blocker 3,4-diaminopyridine (pyridine-3,4-diamine) [233] did not show efficacy in the treatment of ET.

12. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Despite the efforts for investigating new drugs for the pharmacological treatment of ET, the non-selective beta-blocker propranolol and primidone remain as the most efficacious drugs during the last 40 years and therefore are still considered as the first-choice drugs. The results of many other drugs tested in ET patients have not been definitively convincing, although a number of them have shown a beneficial effect. In the experience of the authors, clonazepam, phenobarbital, and topiramate are useful for those patients who report contraindications for the use of propranolol or primidone, or those who experience adverse effects with these drugs (unpublished data). Injections with BTX A are found useful for the treatment of refractory ET affecting upper limbs and, in the experience of the authors, these are especially useful for the treatment of EHT (unpublished data). A recent report by the MDS Task Force on Tremor revealed short-acting propranolol, primidone, and topiramate to be efficacious, and similarly alprazolam and BTX A, with the rest of the drugs analyzed as non-efficacious or with insufficient evidence to be recommended or refused in the treatment of ET [13].

Due to the important contribution of the GABAergic and glutamatergic systems to the pathophysiology of ET [4], it is interesting to test new drugs acting on these systems. Regarding this issue, recent animal studies have shown improvements in harmaline-induced tremor by the extrasynaptic GABAA receptor agonist gaboxadol (THP or 4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-[1,2]oxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-one) in wild type mice but not in knock-out mice for GABA extrasynaptic receptors containing alpha6 and delta subunits [234], and by the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen (4-amino-3-(4-chlorophenyl)butanoic acid) [235]. According to this line, some authors have suggested the potential of neuroactive steroids for the treatment of ET with effects on both extrasynaptic and synaptic GABAA receptors [236] or intrathecal baclofen [237]. In addition, a recent study has shown improvements in harmaline-induced tremor with erythropoietin, which is possibly related to its action as an NMDA receptor antagonist [238], and a recent pilot study in patients diagnosed with ET has suggested that the AMPA receptor antagonist perampanel could be an interesting therapeutic option for ET [128], which needs confirmation by a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study involving a large number of patients.

According to the results of T-type calcium channels inhibitors in experimental models of ET [111, 141], it seems reasonable to test drugs acting on these channels. The results of an important study that has been recently started using a selective modulator of the T-type calcium channel are expected to be published [142]. The potential of gap-junctions inhibitors and adenosine A1 receptor agonists needs to be proven.

Other drugs that are capable of improving harmaline-induced tremor in rodents, but have not been tested in humans include the modulation of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor fingolimod [239], vanillin (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde, acting on the serotoninergic system) [240], and cannabinoid receptor type 1 inhibitors [241]. Finally, because there are genetic and neuropathological data which support the role of the protein LINGO-1 (leucine-rich repeat and immunoglobulin-like domain-containing nogo receptor-interacting protein 1) in the pathogenesis of ET [4, 242], the possible role of antagonists of this protein as a potential pharmacological target for ET [242] has been proposed, but these drugs have not been tested either in experimental models or in ET patients.

Acknowledgements

We recognize the efforts of the personnel of the Library of Hospital Universitario “Príncipe de Asturias”, Alcalá de Henares (Madrid, SPAIN), who retrieved an important number of papers for us.

list of ABBREVIATIONS

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine or serotonin

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)

- BTX A

Botulinum toxin A

- CRMP-2

Collapsin response mediator protein 2 (CRMP-2)

- EHT

Essential head tremor

- ET

Essential tremor

- EVT

Essential voice tremor

- FDG

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose

- GABA

Gamma-aminobutyric acid

- GAD

L-glutamic acid decarboxylase

- LINGO-1

Leucine-rich repeat and immunoglobulin-like domain-containing nogo receptor-interacting protein 1

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- PEMA

Ethyl-2-phenylpropanediamide

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- SV2A

Synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A

- T2000

1,3-Dimethoxymethyl-5,5-diphenylbar-bituric acid

- THP

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Funding

The work at the authors’ laboratory is supported in part by Grants PI15/00303, PI18/00540, and RETICS RD16/0006/0004 from Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain, and IB16170, GR18145 from Junta de Extremadura, Spain. Financed in part with FEDER funds from the European Union.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jimenez-Jimenez F.J., Alonso-Navarro H., Garcia-Martin E., Lorenzo-Betancor O., Pastor P., Agundez J.A. Update on genetics of essential tremor. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2013;128(6):359–371. doi: 10.1111/ane.12148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark L.N., Louis E.D. Essential tremor. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018;147:229–239. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63233-3.00015-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jimenez-Jimenez F.J., de Toledo-Heras M., Alonso-Navarro H., Ayuso-Peralta L., Arevalo-Serrano J., Ballesteros-Barranco A., Puertas I., Jabbour-Wadih T., Barcenilla B. Environmental risk factors for essential tremor. Eur. Neurol. 2007;58(2):106–113. doi: 10.1159/000103646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jimenez-Jimenez F.J., Alonso-Navarro H., Garcia-Martin E., Agundez J.A.G. An update on the neurochemistry of essential tremor. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020;27(10):1690–1710. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666181112094330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Growdon J.H., Shahani B.T., Young R.R. The effect of alcohol on essential tremor. Neurology. 1975;25(3):259–262. doi: 10.1212/WNL.25.3.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koller W.C., Biary N. Effect of alcohol on tremors: comparison with propranolol. Neurology. 1984;34(2):221–222. doi: 10.1212/WNL.34.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeuner K.E., Molloy F.M., Shoge R.O., Goldstein S.R., Wesley R., Hallett M. Effect of ethanol on the central oscillator in essential tremor. Mov. Disord. 2003;18(11):1280–1285. doi: 10.1002/mds.10553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knudsen K., Lorenz D., Deuschl G. A clinical test for the alcohol sensitivity of essential tremor. Mov. Disord. 2011;26(12):2291–2295. doi: 10.1002/mds.23846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyons K.E., Pahwa R., Comella C.L., Eisa M.S., Elble R.J., Fahn S., Jankovic J., Juncos J.L., Koller W.C., Ondo W.G., Sethi K.D., Stern M.B., Tanner C.M., Tintner R., Watts R.L. Benefits and risks of pharmacological treatments for essential tremor. Drug Saf. 2003;26(7):461–481. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200326070-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jimenez-Jimenez F.J., Puertas-Munoz I., de Toledo-Heras M. 2013. Neuroquimica y neurofarmacologia del temblor esencial. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alonso-Navarro H., Jimenez-Jimenez F.J., Garcia-Martin E., Agundez J.A.G. In: Neurochemistry and Neuropharmacology of Essential Tremor.e-book). Frontiers in Clinical Drug Research - CNS and Neurological Disorders. Rhaman A.U., editor. Vol. 2. Bentham Science Publishers; 2013. pp. 110–142. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferreira J.J., Mestre T.A., Lyons K.E., Benito-Leon J., Tan E.K., Abbruzzese G., Hallett M., Haubenberger D., Elble R., Deuschl G. MDS evidence-based review of treatments for essential tremor. Mov. Disord. 2019;34(7):950–958. doi: 10.1002/mds.27700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang A.E., Lees A. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Granneman J.G. The putative beta4-adrenergic receptor is a novel state of the beta1-adrenergic receptor. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;280(2):E199–E202. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.2.E199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray T.J. Treatment of essential tremor with propranolol. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1972;107(10):984–986. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winkler G.F., Young R.R. The control of essential tremor by propranolol. Trans. Am. Neurol. Assoc. 1971;96:66–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pakkenberg H. Propranolol in essential tremor. Lancet. 1972;1:633. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(72)90431-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dupont E., Hansen H.J., Dalby M.A. Treatment of benign essential tremor with propranolol. A controlled clinical trial. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1973;49(1):75–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1973.tb01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winkler G.F., Young R.R. Efficacy of chronic propranolol therapy in action tremors of the familial, senile or essential varieties. N. Engl. J. Med. 1974;290(18):984–988. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197405022901802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolosa E.S., Loewenson R.B. Essential tremor: treatment with propranolol. Neurology. 1975;25(11):1041–1044. doi: 10.1212/WNL.25.11.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McAllister R.G., Jr, Markesbery W.R., Ware R.W., Howell S.M. Suppression of essential tremor by propranolol: correlation of effect with intensity of beta-adrenergic blockade. Trans. Am. Neurol. Assoc. 1976;101:267–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teravainen H., Fogelholm R., Larsen A. Effect of propranolol on essential tremor. Neurology. 1976;26(1):27–30. doi: 10.1212/WNL.26.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray T.J. Long-term therapy of essential tremor with propranolol. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1976;115(9):892–894. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAllister R.G., Jr, Markesbery W.R., Ware R.W., Howell S.M. Suppression of essential tremor by propranolol: correlation of effect with drug plasma levels and intensity of beta-adrenergic blockade. Ann. Neurol. 1977;1(2):160–166. doi: 10.1002/ana.410010210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teravainen H., Larsen A., Fogelholm R. Comparison between the effects of pindolol and propranolol on essential tremor. Neurology. 1977;27(5):439–442. doi: 10.1212/WNL.27.5.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jefferson D., Jenner P., Marsden C.D. Relationship between plasma propranolol levels and the clinical suppression of essential tremor. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1979;7(4):419P–420P. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1979.tb00964.x. [proceedings]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jefferson D., Jenner P., Marsden C.D. Relationship between plasma propranolol concentration and relief of essential tremor. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1979;42(9):831–837. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.42.9.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sorensen P.S., Paulson O.B., Steiness E., Jansen E.C. Essential tremor treated with propranolol: lack of correlation between clinical effect and plasma propranolol levels. Ann. Neurol. 1981;9(1):53–57. doi: 10.1002/ana.410090110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calzetti S., Findley L.J., Gresty M.A., Perucca E., Richens A. Effect of a single oral dose of propranolol on essential tremor: a double-blind controlled study. Ann. Neurol. 1983;13(2):165–171. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calzetti S., Findley L.J., Perucca E., Richens A. The response of essential tremor to propranolol: evaluation of clinical variables governing its efficacy on prolonged administration. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1983;46(5):393–398. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.46.5.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koller W.C., Royse V.L. Time course of a single oral dose of propranolol in essential tremor. Neurology. 1985;35(10):1494–1498. doi: 10.1212/WNL.35.10.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koller W.C. Dose-response relationship of propranolol in the treatment of essential tremor. Arch. Neurol. 1986;43(1):42–43. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1986.00520010038018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calzetti S., Sasso E., Baratti M., Fava R. Clinical and computer-based assessment of long-term therapeutic efficacy of propranolol in essential tremor. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1990;81(5):392–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1990.tb00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koller W.C. Long-acting propranolol in essential tremor. Neurology. 1985;35(1):108–110. doi: 10.1212/WNL.35.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cleeves L., Findley L.J. Propranolol and propranolol-LA in essential tremor: a double blind comparative study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1988;51(3):379–384. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.3.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Troiano A.R., Teive H.A., Fabiani G.B., Zavala J.A., Sa D.S., Germiniani F.M., Camargo C.H., Werneck L.C. Uso do propranolol de acao prolongada em 40 pacientes com tremor essencial e virgens de tratamento: um ensaio clinico nao controlado. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2004;62(1):86–90. doi: 10.1590/S0004-282X2004000100015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koller W.C. Propranolol therapy for essential tremor of the head. Neurology. 1984;34(8):1077–1079. doi: 10.1212/WNL.34.8.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calzetti S., Sasso E., Negrotti A., Baratti M., Fava R. Effect of propranolol in head tremor: quantitative study following single-dose and sustained drug administration. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 1992;15(6):470–476. doi: 10.1097/00002826-199212000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paparella G., Ferrazzano G., Cannavacciuolo A., Cogliati Dezza F., Fabbrini G., Bologna M., Berardelli A. Differential effects of propranolol on head and upper limb tremor in patients with essential tremor and dystonia. J. Neurol. 2018;265(11):2695–2703. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-9052-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alonso-Navarro H., Rubio Ll., Benito-Leon J., Vazquez Rodriguez A., Jimenez-Jimenez F.J. Temblor esencial. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song I.U., Ha S.W., Yang Y.S., Chung Y.A. Differences in Regional Glucose Metabolism of the Brain Measured with F-18-FDG-PET in Patients with Essential Tremor According to Their Response to Beta-Blockers. Korean J. Radiol. 2015;16(5):967–972. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2015.16.5.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zesiewicz T.A., Elble R.J., Louis E.D., Gronseth G.S., Ondo W.G., Dewey R.B., Jr, Okun M.S., Sullivan K.L., Weiner W.J. Evidence-based guideline update: treatment of essential tremor: report of the Quality Standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2011;77(19):1752–1755. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318236f0fd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zappia M., Albanese A., Bruno E., Colosimo C., Filippini G., Martinelli P., Nicoletti A., Quattrocchi G., Abbruzzese G., Berardelli A., Allegra R., Aniello M.S., Elia A.E., Martino D., Murgia D., Picillo M., Squintani G. Treatment of essential tremor: a systematic review of evidence and recommendations from the Italian Movement Disorders Association. J. Neurol. 2013;260(3):714–740. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6628-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Britt C.W., Jr, Peters B.H. Metoprolol for essential tremor. N. Engl. J. Med. 1979;301(6):331. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197908093010617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ljung O. Metoprolol in essential tremor. Lancet. 1980;1(8176):1032. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(80)91474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riley T., Pleet A.B. Metoprolol tartrate for essential tremor. N. Engl. J. Med. 1979;301(12):663. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197909203011215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newman R.P., Jacobs L. Metoprolol in essential tremor. Arch. Neurol. 1980;37(9):596–597. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1980.00500580092022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calzetti S., Findley L.J., Perucca E., Richens A. Controlled study of metoprolol and propranolol during prolonged administration in patients with essential tremor. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1982;45(10):893–897. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.45.10.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calzetti S., Findley L.J., Gresty M.A., Perucca E., Richens A. Metoprolol and propranolol in essential tremor: a double-blind, controlled study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1981;44(9):814–819. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.44.9.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Larsen T.A., Teravainen H. Beta 1 versus nonselective blockade in therapy of essential tremor. Adv. Neurol. 1983;37:247–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leigh P.N., Jefferson D., Twomey A., Marsden C.D. Beta-adrenoreceptor mechanisms in essential tremor; a double-blind placebo controlled trial of metoprolol, sotalol and atenolol. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1983;46(8):710–715. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.46.8.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koller W.C., Biary N. Metoprolol compared with propranolol in the treatment of essential tremor. Arch. Neurol. 1984;41(2):171–172. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1984.04050140069026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gengo F.M., Ulatowski J.A., McHugh W.B. Metoprolol and alpha-hydroxymetoprolol concentrations and reduction in essential tremor. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1984;36(3):320–325. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1984.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dietrichson P., Espen E. Effects of timolol and atenolol on benign essential tremor: placebo-controlled studies based on quantitative tremor recording. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1981;44(8):677–683. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.44.8.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Larsen T.A., Teravainen H., Calne D.B. Atenolol vs. propranolol in essential tremor. A controlled, quantitative study. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1982;66(5):547–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1982.tb03141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koller W.C. Alcoholism in essential tremor. Neurology. 1983;33(8):1074–1076. doi: 10.1212/WNL.33.8.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ogawa N., Takayama H., Yamamoto M. Comparative studies on the effects of beta-adrenergic blockers in essential tremor. J. Neurol. 1987;235(1):31–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00314194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee K.S., Kim J.S., Kim J.W., Lee W.Y., Jeon B.S., Kim D. A multicenter randomized crossover multiple-dose comparison study of arotinolol and propranolol in essential tremor. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2003;9(6):341–347. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(03)00029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuroda Y., Kakigi R., Shibasaki H. Treatment of essential tremor with arotinolol. Neurology. 1988;38(4):650–652. doi: 10.1212/WNL.38.4.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoshii F., Shinohara Y., Takeoka T., Kitagawa Y., Akiyama K., Yazaki K. Treatment of essential and parkinsonian tremor with nipradilol. Intern. Med. 1996;35(11):861–865. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.35.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koller W., Orebaugh C., Lawson L., Potempa K. Pindolol-induced tremor. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 1987;10(5):449–452. doi: 10.1097/00002826-198710000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elble R.J. 2010.