Certain randomized controlled trials suggested that six months’ dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) might be equally effective and probably a safer approach compared with ≥12 months’ therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with drug-eluting stents (DESs).1,2 These findings have influenced current professional guidelines which now endorse DAPT for 6–12 months following DES based PCI. However, the impact of concomitant guideline directed medical therapy (GDMT) such as statins, beta-blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)) on study outcomes in such trials is often overlooked. In a recent meta-analysis of five revascularization trials, compliance with GDMT was shown to be suboptimal and was significantly lower after coronary artery bypass grafting than PCI.3 Based on these observations, we conducted a meta-analysis to compare the differences in GDMT in trials comparing six months’ versus ≥12 months’ DAPT after PCI.

Four trials1,2,4,5 reporting concurrent GDMT (sta-tins, beta-blockers and ACEI/ARB) at least at baseline or discharge were selected using MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL (inception–10 October 2018) (Table 1). Compliance rates for individual therapies were calculated as percent of subjects prescribed each drug at baseline or discharge.3 The “compliance gap” was obtained by calculating the difference in compliance rates of study groups. The estimates were reported as random effects risk differences with 95% confidence intervals. Q statistics and I2 statistics were used to assess heterogeneity. Quality assessment of trials was done on Cochrane risk of bias tool. The literature search, data extraction and bias risk assessment was done by two authors (SUK and MSK) independently. Moment of methods meta regression analysis was conducted between GDMT and all-cause mortality and cardiovascular outcomes. Statistical significance was set at 5%. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (version 3) was used for meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of trials and participants.

| Study/year | DAPT duration | No. of patients | Age (mean) | Men (%) | Stable CAD (%) | ACS (%) | Medical therapy at baseline (%) | Medical therapy at discharge (%) | CRoB | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statin | Beta- blockers | ACE I/ARB | GDMT | Statin | Beta- blockers | ACE I/ARB | GDMT | ||||||||

| EXCELLENT/20121 | 6 months | 722 | 63.0 | 65.1 | 48.9 | 51.1 | - | - | - | - | 85 | 60.1 | 65.8 | 69.2 | ****** |

| 12 months | 721 | 62.4 | 63.9 | 48.0 | 52.0 | - | - | - | - | 81.9 | 62.6 | 66.7 | 69.4 | ||

| PRODIGY/20125 | 6 months | 983 | 67.9 | 76.0 | 25.4 | 74.6 | 91.0 | 84.6 | 87.0 | 87.3 | 90.7 | 84.0 | 87.7 | 87.4 | ****** |

| 24 months | 987 | 67.8 | 77.4 | 26.0 | 74.2 | 92.1 | 83.6 | 84.3 | 86.3 | 89.9 | 83.3 | 86.4 | 86.5 | ||

| ISAR SAFE/20142 | 6 months | 1998 | 67.2 | 80.7 | 59.5 | 39.8 | 95.0 | 83.2 | 81.7 | 86.7 | - | - | - | - | ******* |

| 12 months | 2007 | 67.2 | 80.5 | 59.1 | 40.3 | 94.4 | 83.8 | 82.7 | 87.0 | - | - | - | - | ||

| SMART DATE/20184 | 6 months | 1357 | 62.0 | 74.9 | 2.3 | 97.7 | - | - | - | - | 89.3 | 70.8 | 69.7 | 76.6 | ****** |

| 12 months | 1355 | 62.2 | 75.9 | 1.7 | 98.3 | - | - | - | - | 91.4 | 73.7 | 69.9 | 78.3 | ||

Cochrane risk of bias scale: comprises seven components: random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete data reporting (attrition bias), selective reporting (reporting bias) and other bias. Each component carries one star and 5 or more stars represents good quality.

ACEI/ARB: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; ACS: Acute Coronary Syndrome; CAD: coronary artery disease; CRoB: Cochrane risk of bias; EXCELLENT: Efficacy of Xience/Promus Versus Cypher to Reduce Late Loss After Stenting; GDMT: guideline directed medical therapy; ISAR SAFE: Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Safety and Efficacy of 6 Months Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After Drug-Eluting Stenting; PRODIGY: Prolonging Dual Antiplatelet Treatment After Grading Stent-Induced Intimal Hyperplasia); SMART-DATE: six-month versus 12-month or longer dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome.

Over all compliance with GDMT at baseline was 84.0% (75–90%; p < 0.001). Statins had the highest compliance rates: 90.7% (80.8–95.7%, p < 0.001), followed by ACEI/ARB: 81.5% (75.5–86.3%, p < 0.001) and beta-blockers: 79.8% (70.5–86.7%, p < 0.001). There was a slight reduction in prescription rates of medical therapy at discharge: GDMT: 77.5% (69.6–83.9%, p < 0.001], statins: 87.8% (83.9–90.9%, p < 0.001), beta-blockers: 71.9% (69.6–83.9%, p < 0.001(ACEI/ARB: 72.4% (60.9–81.5%, p < 0.001). The compliance rates for proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) at baseline: 31.5% (21.5–43.6%, p < 0.001) and discharge: 34.6% (32.5–36.7%, p < 0.001) were lowest.

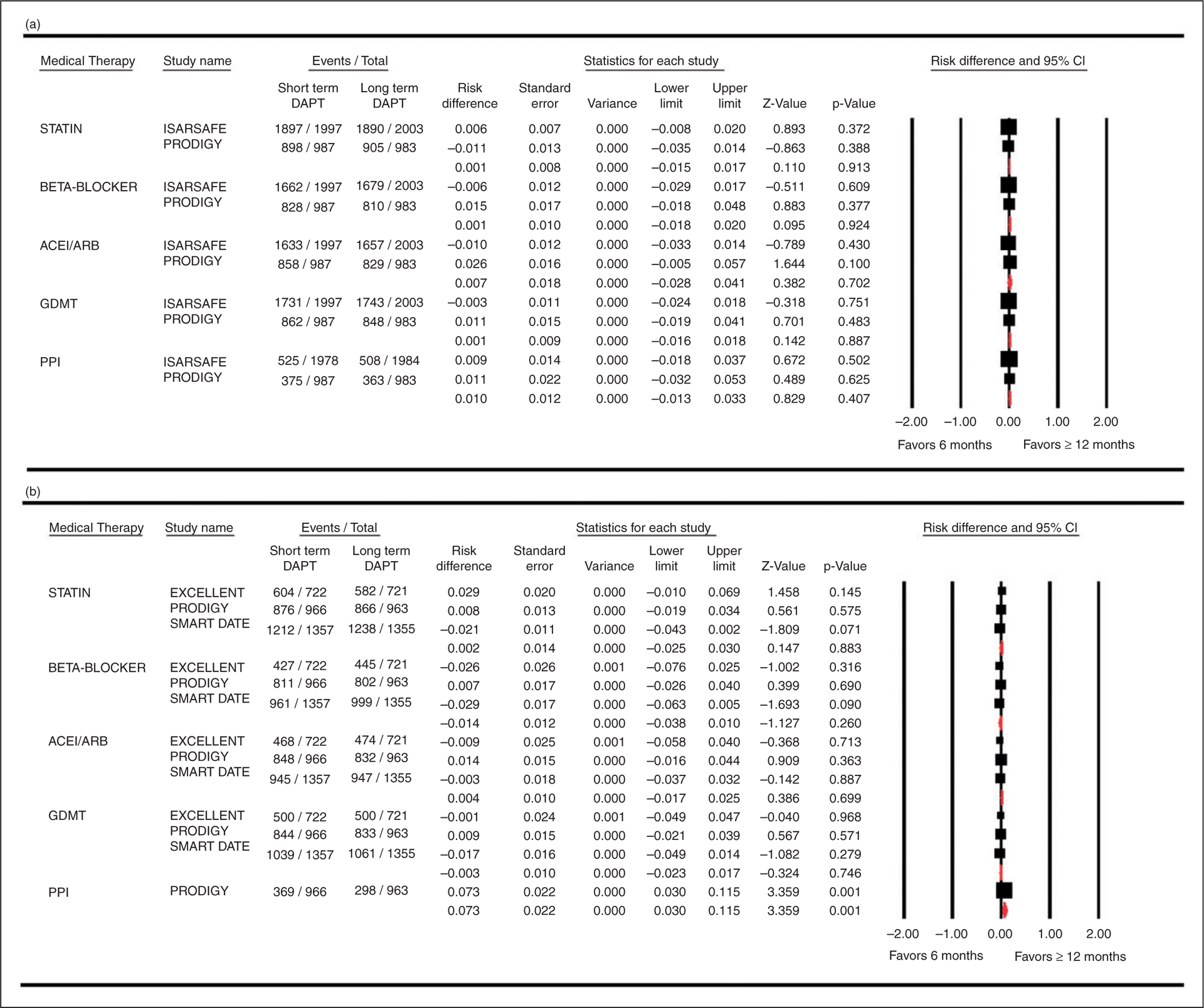

There were no significant differences between compliance rates of medical therapy among six versus ≥12 months’ DAPT groups (Figure 1). Hence, the absolute difference in GDMT did not result in significant change in all-cause mortality (slope: 0.00009, p = 0.58), myocardial infarction (slope: −0.00017, p = 0.49), stroke (slope: −0.00014, p = 0.43) and stent thrombosis (slope: −0.00006, p = 0.62).

Figure 1.

Forest plot comparing medical therapy compliance rates among six months’ versus ≥ 12 months’ dual antiplatelet therapy groups. (a) Medical therapy at baseline and (b) Medical therapy at Discharge.

ACEI/ARB: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; CI: confidence interval; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; GDMT: guideline directed medical therapy; PPI: proton pump inhibitor

Overall GDMT compliance in both arms of these trials was better than compliance rates reported in meta-analysis of revascularization trials (~53% to 67%).3 The comparable compliance rates in both the groups also validate the impression that cardiovascular benefits of six months’ DAPT in these trials were unlikely to be skewed by imbalance in GDMT. Prescription rates of PPIs were low, potentially reflecting ongoing controversy regarding their use in different professional guidelines. Similar to a former report,3 there was a modest decline in compliance rates from baseline to discharge. Compliance with statins was the highest, while both beta-blockers (60% to 83%) and ACEI/ARBs (61% to 87%) had the lower and variable compliance rates across the trials. These findings raise the concern that even in well-conducted trials, the drug compliance remains suboptimal.3

These results are consistent with real world data. A 147,785 cohorts’ study from The Netherlands suggested a large discrepancy between guideline recommendations and prescription rates of statin therapy.6 Hence, there is an utmost need to improvise such strategies which can enhance guideline directed clinical practice and improve patients’ adherence to medications. For instance, one approach could be switching from different treatment regimens to a fixed-dose combination pill (polypill). In the UMPIRE trial, polypill based therapy (aspirin 75 mg, simvastatin 40 mg, lisinopril 10 mg, and either hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg or atenolol 50 mg) showed consistent and identical cardiovascular risk reductions compared with a wide range of usual care patterns of antiplatelets, statin and antihypertensive medications.7

This study is limited due to general lack of reporting of drug prescription rates in the clinical trials leading to inclusion of lesser number of trials than expected. For the same reason, drug compliance beyond the discharge time point could not be assessed. Finally, since we estimated medication adherence rates from prescription rates, the possibility of over estimating compliance rates cannot be ignored.3

In summary, although there were no significant differences in prescription rates of GDMT among six versus ≥12 months’ DAPT groups, GDMT adherence rates varied from being low to moderate across the included trials. These observations call for improving the strategies to enhance compliance with GDMT among participants of trials to reduce potential risk of bias due to imbalance in medical therapy.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Gwon HC, Hahn JY, Park KW, et al. Six-month versus 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy after implantation of drug-eluting stents: The Efficacy of Xience/Promus Versus Cypher to Reduce Late Loss After Stenting (EXCELLENT) randomized, multicenter study. Circulation 2012; 125: 505–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulz-Schupke S, Byrne RA, Ten Berg JM, et al. ISAR-SAFE: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 6 vs. 12 months of clopidogrel therapy after drug-eluting stenting. Eur Heart J 2015; 36: 1252–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinho-Gomes AC, Azevedo L, Ahn JM, et al. Compliance with guideline-directed medical therapy in contemporary coronary revascularization trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71: 591–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahn JY, Song YB, Oh JH, et al. 6-month versus 12-month or longer dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome (SMART-DATE): A randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2018; 391: 1274–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valgimigli M, Campo G, Monti M, et al. Short- versus long-term duration of dual-antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting: A randomized multicenter trial. Circulation 2012; 125: 2015–2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balder JW, de Vries JK, Mulder DJ, et al. Time to improve statin prescription guidelines in low-risk patients? Eur J Prev Cardiol 2017; 24: 1064–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lafeber M, Spiering W, Visseren FL, et al. Impact of switching from different treatment regimens to a fixed-dose combination pill (polypill) in patients with cardiovascular disease or similarly high risk. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2017; 24: 951–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]