Abstract

Objectives:

Physician-assisted death (PAD), also known as medical assistance in dying, of patients with a psychiatric disorder (PPD) is a global issue of debate. In most jurisdictions that allow PAD, irremediable suffering is a legal requirement, how to apply the concept of irremediability to PPD remains challenging. The aim of this article is to identify the main arguments concerning irremediability in the debate about PAD of PPD and give directions for further moral deliberation and empirical research.

Methods:

Systematic searches in MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO were combined with 4 additional search strategies. All conceptual-ethical articles, quantitative and qualitative empirical studies, guidelines, case reports, and commentaries that met the inclusion criteria were included, and a qualitative data synthesis was used to identify recurring themes within the literature. The study protocol was preregistered at the Open Science Framework under registration code: thjg8.

Results:

A total of 50 articles met the inclusion criteria. Three main arguments concerning irremediability were found in the debate about PAD of PPD: uncertainty, hope, and treatment refusal.

Conclusions:

Uncertainty about irremediability is inevitable, so which level of certainty is morally required should be the subject of moral deliberation. Whether PAD induces or resolves hopelessness is an empirical claim that deserves clarification. Treatment refusal in search of PAD raises questions about treatment efficacy in this patient group and about decision-making in the context of the physician–patient relationship. Going forward, more attention should be given to epidemiological research and to specific challenges posed by different psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: physician-assisted death, psychiatry, irremediability, ethics, review

Abstract

Objectifs :

Le suicide assisté par un médecin (SAM), qui porte plus souvent le nom d’aide médicale à mourir (AMAM), en ce qui concerne les patients souffrant d’un trouble psychiatrique (PTP) fait l’objet d’un débat mondial. Dans la plupart des administrations qui autorisent le SAM, un problème de santé irrémédiable est un critère légal, mais comment appliquer le concept de l’irrémédiabilité à des patients souffrant d’un trouble psychiatrique demeure épineux. Le but du présent article est d’identifier les principaux arguments portant sur l’irrémédiabilité dans le débat sur le SAM ou les PTP et d’offrir des directives pour d’autres délibérations morales et la recherche empirique.

Méthodes :

Des recherches systématiques dans medline, embase et psycinfo ont été combinées avec quatre stratégies de recherche additionnelles. Tous les articles conceptuels-éthiques, les études empiriques quantitatives et qualitatives, les lignes directrices, les études de cas et les commentaires qui satisfaisaient aux critères d’inclusion ont été inclus et une synthèse des données qualitatives a servi à dégager les thèmes récurrents de la littérature. Le protocole de l’étude a été préinscrit à l’Open Science Framework, sous le code thjg8.

Résultats :

Cinquante articles satisfaisaient aux critères d’inclusion. Trois arguments principaux portant sur l’irrémédiabilité ont été tirés du débat sur le SAM des PTP: l’incertitude, l’espoir et le refus de traitement.

Conclusions :

L’incertitude au sujet de l’irrémédiabilité est inévitable, donc le degré de certitude qui est moralement requis devrait être soumis à la délibération morale. Déterminer si le SAM induit ou résout le désespoir est une allégation empirique qui mérite une clarification. Le refus de traitement dans la recherche du SAM soulève des questions sur l’efficacité du traitement dans ce groupe de patients et sur la prise de décisions dans le contexte de la relation médecin-patient. Pour aller de l’avant, il faudrait prêter davantage attention à la recherche épidémiologique et aux problèmes spécifiques posés par différents troubles psychiatriques.

Introduction

Physician-assisted death (PAD), also known as medical assistance in dying, is allowed in a growing number of jurisdictions, which include Canada, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxemburg, Switzerland, Colombia, Japan, the United States, and Australia.1 Other countries are debating legalization of PAD. Many jurisdictions explicitly or implicitly ban patients with psychiatric disorders (PPD) from accessing PAD, but this is not the case in the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxemburg, and Switzerland.2 In Belgium and the Netherlands, the prevalence of PAD due to psychiatric suffering has increased over the past years.3,4 In the Netherlands, 1.1% of all cases of PAD in 2018 was due to psychiatric suffering (67 psychiatric cases in total).3

Most jurisdictions require that the patient is in an irremediable condition. This is one of the elements that make PAD of PPD more controversial than PAD of other patients. When can we say that a psychiatric disorder is irremediable? What arguments play a role regarding this core criterion for PAD?

In this scoping review, we systematically investigate the main arguments concerning irremediability in the debate about PAD of PPD. We will identify 3 core issues, namely, arguments concerning uncertainty of diagnosis and prognosis, arguments concerning hope, and arguments concerning treatment refusal. We will show that the debate on these issues is not conclusive and that there is a need for empirical research on the one hand and normative deliberation on the other hand.

Methods

While performing this systematic review, the PRISMA scoping review guidelines were followed.5 The project was preregistered on the Open Science Framework on February 1, 2019, and can be accessed there.6 Ethical approval or participant informed consent was not required for this study.

Search

A systematic search was performed in PubMed, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO on November 20, 2019. We based our search on the PALETTE guidelines.7 The search strategy combined 3 components and their synonyms: psychiatry, irremediability, and physician assisted death. A list of search terms and the syntax for PubMed can be found in Online Appendices 1 and 2. No language or publication year filters were used. After completing the database search, 4 additional search strategies were performed; first, a backward citation screening on all articles from the database search that were included. Second, forward citation tracking in Google Scholar using the 2016 landmark paper by Kim et al.8 Third, we screened the table of contents of the unindexed special edition on Medical Aid in Dying of the Journal of Ethics in Mental Health on November 20, 2019. This special issue contains relevant contributions to the debate on PAD for PPD. While appraising articles from this journal and when describing their results, we carefully assessed the quality of the papers. Fourth, we manually included Dutch and Belgian reports and guidelines that fall within the inclusion criteria but are not available in any online scientific database. If full texts were unavailable, we contacted the corresponding author for a copy.

Source Selection

We included all conceptual-ethical articles, quantitative and qualitative empirical studies, guidelines, case reports, and commentaries if they addressed irremediable suffering due to psychiatric illness to a background of PAD. We excluded non-English or non-Dutch articles, articles without an available full text, articles that only mention irremediability in passing, and articles addressing irremediable suffering due to nonpsychiatric illness. AR and SvV performed title and abstract screening; SvV performed full text evaluation.

Data Synthesis

After full text evaluation, text segments from all included articles addressing irremediability were extracted from the articles and anonymized. All authors separately coded these segments which lead to the identification of recurring themes emerged from the literature. All definitions of irremediability and all the viewpoints that were found most important and representative for the debate on PAD of PPD were included after discussion between all authors. Since most of the sources were conceptual essays, no structural data charting or systematic critical appraisal was indicated.

Results

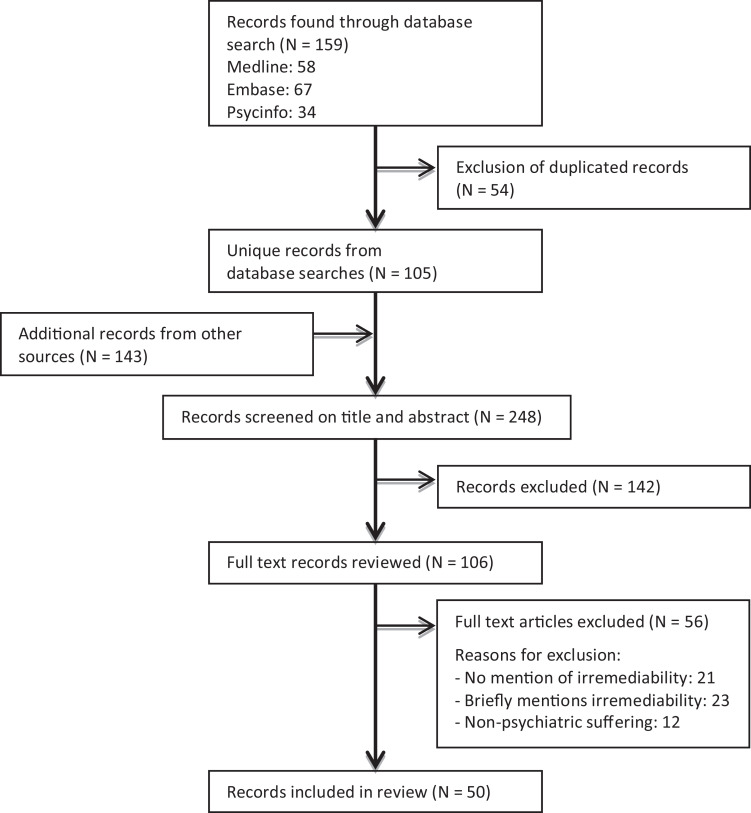

The database searches yielded 105 unique records, and the additional search strategies yielded 143 records (Figure 1). After full text evaluation, 50 articles were included (Table 1). Through a qualitative synthesis of the literature, we found 3 main arguments concerning irremediability in the debate about PAD of PPD: acceptability of uncertainty, influence of hope, and role of treatment refusal.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the systematic search and study selection process.

Table 1.

Overview of Included Articles. Subdivided into Conceptual Studies, Legal Studies, Guidelines, and Empirical Studies.

| Conceptual Studies | ||

| Source | Article Type | Main Argument Regarding Irremediability |

| Schoevers et al.9 | Essay | Predictions of outcome for individual patients are not very reliable and more complicated than in somatic medicine; therefore, we should not allow physician-assisted death (PAD) for patients with a psychiatric disorder (PPD). |

| Berghmans10 | Commentary | Describes the view of the Dutch Supreme Court that a patient’s situation cannot be considered hopeless if he or she freely refuses a meaningful treatment option. |

| Burnside11 | Commentary | The uncertainty that stems from the nature of psychiatric illness and the long survival both complicate PAD for PPD compared to PAD for somatic disease. |

| Kissane and Kelly12 | Essay | (1) The demoralization syndrome can be seen as a separate clinical entity from depression. (2) Counter transferal feelings of hopelessness should be accounted for when considering PAD for PPD. (3) Prognostic uncertainty is substantial in psychiatry; therefore, PAD should be banned. |

| Kelly and McLoughlin13 | Editorial | With the exception of severe neurodegenerative diseases, it is essentially impossible to describe any mental illness as incurable because it is extremely difficult to predict what disease progression will be. |

| Naudts et al.14 | Essay | (1) The Diagnostic Statistical Manual is a scientifically weak basis on which to base an important decision as PAD. (2) The prognosis of psychiatric disorders is too uncertain; therefore, PAD should not be available for psychiatric patients. |

| Appel15 | Commentary | The window of opportunity for discovering effective treatment is longer in psychiatry than in somatic medicine, but the patient should be able to decide whether he or she wants to wait for this. |

| Lopez et al.16 | Case study | Treatment of anorexia nervosa can become futile; therefore, a palliative approach may be warranted. |

| Vandenberghe17 | Commentary | Discusses the complexities of giving up hope and of labeling suffering due to a personality disorder as irremediable. |

| Brown et al.18 | Case report | Treatment refractoriness is an empirical observation where the prognosis must be known and poor. If the prognosis is uncertain, (assisted) suicide is not rational. |

| Cowley19 | Commentary | (1) Because of the uncertain prognosis of depression, we should err on the side of keeping patients alive. (2) If patients truly want to die (unassisted), suicide is an option that better safeguards autonomy. |

| Berghmans and Widdershoven20 | Case study | “Offering PAS to a patient with a mental illness who suffers unbearably, enduringly and without prospect of relief does not necessarily imply taking away hope and can be ethically acceptable.” |

| Schuklenk and Vathorst21 | Essay | If patients with TRD competently request PAD, they should be granted access. No argument against PAD is strong enough to infringe their right to autonomy. |

| Broome and de Cates22 | Commentary | It is very unlikely that a patient with TRD is both competent to make decisions about ending their own life and that the same individual has no prospect for relief of their suffering. |

| Cowley23 | Commentary | “We can never be sufficiently certain of the hopelessness, and we should therefore incline away from such a serious and irreversible decision as assisting suicide.” |

| Pienaar24 | Essay | (1) Gives 4 different and complementary definitions of futility according to Bernstein, (2) reviews different epidemiological studies that show that treatment resistance in depression, schizophrenia, anxiety, and eating disorders does exist. |

| Kim and Lemmens25 | Commentary | (1) Psychiatric irremediability is inherently vague and unreliable. (2) Accepting treatment refusal ignores the core clinical imperative of helping patients through periods of sustained suffering. |

| Olié and Courtet26 | Essay | (1) Determining whether psychiatric suffering is irremediable is complex. (2) Treatment of psychological pain is currently undervalued. |

| Hodel and Trachsel27 | Commentary | (1) When suffering is treatment-resistant, care goals should be shifted toward patient oriented palliative care. (2) A disproportionate focus on suicide prevention can lead to a poorer quality of life for the patient. |

| Blikshavn et al.28 | Essay | (1) TRD is not a clinical entity and psychodynamic and social treatments are undervalued in research about TRD. (2) The therapeutic significance of hope must be acknowledged; for giving up, hope might be a self-fulfilling prophecy. |

| Appelbaum29 | Essay | When the suffering of patients who refuse treatment is seen as irremediable, a substantial proportion of people with mental disorders seeking assisted death could probably obtain relief from other available approaches. |

| Yarascavitch30 | Essay | (1) Deliberate attention must be paid to the nonmedical factors that contribute to the experience of irremediable suffering. (2) The right to refuse treatment is problematic in the context of mental disorders. |

| Kirby31 | Essay | (1) Irremediability is harder to establish in psychiatric than in somatic medicine. (2) Because psychiatric disorders are not terminal, new therapies may be discovered that are beneficial to the patient. (3) Irremediability of psychiatric suffering is especially hard to determine in adolescent patients. |

| Steinbock32 | Conceptual article | (1) There is no consensus over what constitutes TRD. (2) Uncertainty about disease progression pervades most areas of medicine; competent patients should be able to make treatment choices including PAD. |

| Kelly33 | Commentary | “With mental illness, there is no point at which we can say that a person’s illness is untreatable or that their suffering cannot be alleviated.” Therefore, PAD should not be accessible for psychiatric patients. |

| Reel et al.34 | Book chapter | Hope is not always a benign entity, false hope can be harmful if it leads to prolonged suffering, loss of dignity and self, and fractures in the therapeutic alliance. |

| Bay35 | Lecture transcript | (1) Worries that irremediable psychiatric suffering is caused by a disjointed and underfunded health care system as well as a society that is persistently hostile to this population. (2) Because of the episodic nature of some mental illnesses, a 1-year waiting period should be considered in the case of mental illness. |

| Rooney et al.36 | Case report | (1) It is possible to determine whether psychiatric suffering is irremediable. (2) The relative long survival of psychiatric patients who suffer irremediably makes exclusion from PAD especially harmful. |

| Dembo et al.37 | Essay | (1) Psychiatric suffering can be irremediable. (2) The possibility of future treatments is no reason to ban PAD for PPD. |

| Simpson38 | Essay | (1) Because of the complexity of predicting, individual disease progression PAD due to psychiatric suffering should not be possible. (2) Carers and clinicians should always stay hopeful, even when patients are suicidal. |

| Appelbaum39 | Essay | (1) It is very complicated to determine irremediable psychiatric suffering. (2) Giving up hope leads to hopelessness. |

| Demyttenaere and Van Duppen40 | Opinion/review | The concept of TRD is highly questionable, including estimation and evaluation of treatment effect (and of spontaneous evolution), this should be taken into account when deciding about PAD. |

| Guidelines | ||

| Source | Article Type | Description of Contents |

| The Flemish Society of Psychiatry41 | Advisory document | Translates the Dutch guideline on psychiatric PAD from 2008 to the current medical and legal practice in Flanders (the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium). |

| Dutch Society of Psychiatry42 | Guideline | Offers guidelines to Dutch psychiatrists about how to act when a patient requests PAD. It outlines 4 different phases in the process of PAD: the request phase, the exploration phase (with a clear paragraph on irremediability), the (external) examination phase, and the actual assistance in dying. |

| Dutch Regional Euthanasia Review Committees.43 | Guideline | Prescribes how the Dutch Euthanasia Review committees should review individual cases based on the Dutch Euthanasia law and available jurisprudence. There is a separate chapter on PAD due to psychiatric disorders. |

| Legal studies | ||

| Source | Article Type | Main Arguments Concerning Irremediability |

| Legemaate and Gevers44 | Case series | Describes the Supreme Court ruling that rejects assisted suicide in cases of mental suffering if there is a realistic alternative to alleviate the suffering. |

| de Boer and Oei.45 | Legal case study | Advises how the assessment of irremediability and expert consultation should be formalized from a legal point of view. |

| Walker-Renshaw et al.46 | Essay | (1) Describes the definition of a grievous and irremediable condition as given by the Canadian Supreme Court in which a central principle is that only treatments have to be tried that are acceptable to the patient, (2) examines whether PAD is justified within the Canadian law on medical aid in dying. |

| Downie and Dembo47 | Essay | Argues that psychiatric suffering can be irremediable and that this can be ground for PAD under current Canadian law. |

| Shaffer et al.2 | Review | Gives an overview of all jurisdictions that allow PAD at that time and investigate whether psychiatric patients have access and identifies irremediability as an important topic where legislation differs. |

| Empirical studies | ||

| Source | Article Type | Methods and Findings on Irremediability |

| Groenewoud et al.48 | Questionnaire among psychiatrists | Methods: A total of 205 psychiatrists with experience in PAD requests filled in a questionnaire about their experiences. Findings on irremediability: In total, 91% of the psychiatrists thought that incurability and hopelessness were important demands for PAD; 64% of psychiatric patients that requested PAD refused at least one treatment. |

| Thienpont et al.49 | Quantitative medical file review | Methods: A total of 100 medical files of psychiatric patients who requested PAD were retrospectively analyzed. Findings on irremediability: It describes that all 100 patients suffered “chronic, constant and unbearable, without prospect of improvement, due to treatment resistance.” Remarkably, 38 of these patients were later referred for further reviewing or offered additional treatment. |

| Kim et al.8 | Quantitative case-series analysis | Methods: The study analyzed 66 case reports of Dutch psychiatric patients who died through PAD between 2011 and 2014. Findings on irremediability: In total, 56% of patients refused at least some form of treatment. In 20% of the cases (13/66), psychiatrists disagreed about irremediability. |

| Verhofstadt et al.1 | Qualitative testimonial-analysis | Methods: Testimonials from 26 psychiatric patients who requested euthanasia were qualitatively analyzed using direct content analysis. Findings on irremediability: Hopelessness and incurability were both important factors that contributed to the patient’s suffering. |

| Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al.50 | Questionnaire among psychiatrists | Methods: A total of 248 psychiatrists with experience in PAD requests filled in a questionnaire about their experiences. Findings on irremediability: The fact that there were still treatment possibilities is the most common reason for psychiatrists to refuse PAD (53%); 56% of the respondents thought it is possible to establish irremediability; 70% of psychiatrists believe that future treatment options should not be taken into account when deciding about irremediability. |

| Qualitative interviews among psychiatrists | Methods: A total of 10 psychiatrists who performed PAD were interviewed in depth. Findings on irremediability: Several psychiatrists acknowledged that ascertaining whether suffering is irremediable and unbearable is the most difficult of all the legal demands. | |

| van Veen et al.51 | Quantitative case series analysis | Methods: A total of 35 case reports of Dutch psychiatric patients who died through PAD between 2015 and 2017 were analyzed. Findings on irremediability: In 11% of the cases (4/35) consulted, psychiatrists disagreed about irremediability. |

| Tuffrey-Wijne et al.52 | Qualitative analysis of 9 cases reports | Methods: The study analyzed 9 case reports of Dutch patients with autism or intellectual disability who died through PAD between 2012 and 2016. Findings on irremediability: It shows that the Dutch PAD due care criteria do not appear to act as adequate safeguards for people with intellectual disabilities and/or autism spectrum disorder. |

| Nicolini et al.53 | Quantitative case series analysis | Methods: The study analyzed all psychiatric PAD cases involving personality- and related disorders published by the Dutch regional euthanasia review committees (N = 74, from 2011 to October 2017). Findings on irremediability: Past psychiatric treatments varied, e.g., hospitalization and psychotherapy were not tried in 27% and 28%, respectively; 51% of patients refused some form of treatment. |

Note: PAD = physician-assisted death; PPD = patients with a psychiatric disorder; TRD = treatment-resistant depression.

Arguments Concerning Uncertainty of Diagnosis and Prognosis

Uncertainty of diagnosis and prognosis is a recurring theme in the debate about PAD of PPD. Empirical studies from the Netherlands show that there is disagreement about irremediability between psychiatrists in 11% to 20% of the PADs due to psychiatric suffering.8,51 Several authors cite clinical studies that show that some psychiatric patients will never recover.24,37,47 But whether these “truly irremediable” patients can be identified is subject of debate. Rooney et al. argue that irremediability can be predicted for individual depressed patients with help of staging models.36 A questionnaire in 2016 among 248 Dutch psychiatrists found that 70% disagreed with the statement that it is impossible to assess whether a psychiatric patient suffers irremediably and unbearably, 12% agreed with this statement, and 17% was neutral.50 In the ethical debate, however, many authors argue that it is impossible to reliably differentiate between patients who have a chance of recovery and those who do not.9,11,13,17,26,28 Two reasons are often mentioned for questioning irremediability: the nature of psychiatric illness and the nature of psychiatric treatment.

The Nature of Psychiatric Illness

In the discussion on the irremediability of psychiatric suffering, often a comparison is made with cancer. Several authors argue that the distinction between remediable and irremediable forms of cancer is fairly straightforward for 2 reasons. First, cancer has a clear biological basis. Second, for most forms of cancer, it can be predicted whether and, within certain boundaries, when they will lead to death.9,15,54,55 Various authors point out that psychiatric suffering differs in both aspects. First, the current psychiatric diagnostic model is said to describe syndromes and therefore offers no insight in the underlying biological, psychodynamic, or social factors, hampering the possibility of accurate prediction of disease progression.9,14,28,30,40 Second, psychiatric disorders themselves are said not to be lethal, except maybe for severe eating disorders.16 Therefore, patients may have a life expectancy of decades.12,32 Various authors argue that it may be possible that in this period, new treatments are discovered, which can eventually help relieve suffering.11,22 However, when asked about the possibility of future new treatments, 56% of 248 Dutch psychiatrists thought that this should not be taken into account when deciding about PAD, 22% thought it should be taken into account, and 22% were neutral.50

The Nature of Psychiatric Treatment

The second reason for questioning irremediability is the nature of psychiatric treatment. First, it is argued that the broad range of biomedical and psychotherapeutic approaches offers so many (combined) treatment options that a claim about irremediability is practically impossible.31 Second, authors argue that psychiatrists apply all these therapies dynamically, which can make it hard to determine when and why specific psychiatric treatments work and also when and why they stop working.9 Third, authors mention that sometimes when therapists and patients stop trying to control symptoms, paradoxically, the chances of recovery improve. This is said to happen when a switch is made from a symptom reduction to an acceptance-based therapy.26,27,28 It is also argued that a certain risk of self-harm may have to be accepted in order for the patient to recover.56 Fourth, Tuffrey-Wijne et al. question whether medical terms such as ‘treatment refractory symptoms’ are suitable for life-long disabilities such as autism spectrum disorder.52

Consequences for PAD of PPD

In the light of the uncertainty about diagnosis and prognosis on the one hand, and treatment on the other hand, authors reach different conclusions about the acceptability of PAD of PPD. Many authors want to restrict access to PAD for psychiatric patients.9,12,18,19,23,33 In their view, the harm of assisting in the death of a patient who might recover justifies a ban on PAD for all psychiatric patients. As Cowley et al. put it: “if in any sort of doubt, a psychiatrist should avoid any irreversible decisions, and should err on the side of keeping her alive.”19 Proponents of PAD of PPD disagree with this assessment and argue that uncertainties are not a good enough reason to infringe on patient autonomy and continue unbearable suffering.37,32 When a competent patient understands that it is uncertain whether their suffering is truly irremediable, it is up to the patient to decide whether or not to continue living with those chances.15 Other proponents of PAD argue that the harm of letting a majority of truly irremediable patients suffer could be greater than the voluntary death of a minority that might recover spontaneously or benefit from future treatment.21,24,36 Also, the nonlethality argument is disputed altogether, as patients may die through suicide, which may be regarded as worse than dying through PAD.36 A third viewpoint balances these 2 positions, arguing that a reasonable level of uncertainty can be acceptable.20,45 What counts as reasonable depends on the situation and has to be determined through dialogue between doctor and patient. This approach has a long tradition in the Netherlands.57 It is embedded in the Dutch euthanasia law as well as in different guidelines addressing the subject of PAD of PPD.42,43 However, worries about the Dutch system have been uttered, as it is said to be based on “inherently vague” criteria.25

Arguments Concerning Hope

Hope is an often-discussed factor in the debate about PAD of PPD. Sometimes hopelessness is simply used as a synonym for an absent chance of recovery.23,48 But more often hopelessness is seen as a state of mind, both for the patient and the doctor, not necessarily related to the actual prognosis.12,17,28,38 A qualitative analysis of testimonies by psychiatric patients shows that feelings of hopelessness are an important and recurring reason for requesting PAD.1

Remaining hopeful is seen as a basic therapeutic tool for the psychiatrist and as a basic condition for recovery of the patient. Opponents of PAD of PPD argue that it is unethical for psychiatrists to admit hopelessness through participating in PAD.12,28,38 This is expressed in the following quote by Simpson et al.: “we must always seek the possibility of finding ways to help people with their suffering and help them see their ongoing life as valuable and vital, for themselves and for others who know them and love them.” 38 It is argued that the option of PAD entails a self-fulfilling prophecy: It will diminish hope in a patient, which further diminishes their motivation for treatment, which adds to the irremediability.28 Furthermore, opening the door to PAD is seen as a dangerous message to all psychiatric patients, indicating that there indeed are hopeless conditions.28,39 It is, however, also argued that hopelessness is already present in patients requesting PAD and is not introduced into a therapeutic relationship by discussing it.36 Other authors argue that the possibility of PAD could give patients hope that there is an end to their suffering, thereby motivating them to pursue treatment.17 One study found that 8 of the 48 psychiatric patients who were granted PAD in the end did not need it because “simply having this option gave them enough peace of mind to continue living.”49 Furthermore, it has been argued that giving false hope to patients contemplating death might lead to distancing from the therapist and therefore an increase in suicidality.17 False hope may be harmful as is expressed in the following quote: “Although patients then may get support, attention, and care from others, the existential despair which is expressed in the request for PAS is not being seriously addressed.”20 Also, authors worry that a psychiatrist who harbors false hope might resort to invasive and useless treatment that might significantly detract from the patient’s quality of life and lead to loss of dignity.27,34

Arguments Concerning Treatment Refusal

A further theme concerns the role of treatment refusal in PAD of PPD. Treatment refusal is not only a theoretical issue; as early as 1997, in a questionnaire study among 204 Dutch psychiatrists who had experience with patients requesting PAD, it was shown that 64% of the patients who requested PAD refused a form of treatment.48 More recently, in a 2016 study of 66 case summaries of Dutch patients who received PAD due to psychiatric suffering between 2011 and 2014, it was found that 56% of the patients had refused at least 1 treatment, ranging from psychotherapy to medication or ECT. Reasons for refusal were lacking motivation in 29% of all cases, concern about adverse effects or risks of harm in 18%, and doubts about efficacy in 15%. It was also reported that personality disorders play a common role in treatment refusal.8 Another study from 2019 on the case summaries of patients with personality disorders found that 51% refused some form of treatment, suggesting that treatment refusal might actually be slightly lower in this subgroup.53

Jurisdictions allowing PAD formulated different regulations concerning treatment refusal. In 1994, the Dutch Supreme Court ruled that a patient refusing appropriate treatment does not suffer irremediably, implying that in such a case, PAD is not justified.10,42,43 Treatment is defined as appropriate if current medical opinion states that the condition of the patient can be alleviated within a reasonable time period and with a reasonable balance of burdens and benefits.41,42,43 Again, consensus has to be reached through dialogue between the patient and physician for PAD to be justified.42 Several Dutch authors defend this policy throughout the debate.20,36 Canada’s assisted dying law is more patient-centered, stating that suffering is irremediable when all treatments acceptable to the patient have failed, thus leaving more room for PAD after treatment refusal.2,41 This patient-centered view on irremediability is held by right-to-die societies and is supported by several authors throughout the debate.2,44,46,47 Opponents of PAD of PPD argue that the patient-centered view on treatment refusal will most likely lead to deaths that could have been prevented by offering treatment.29,30,39

Discussion

This systematic review synthesized literature addressing irremediability in the debate about PAD for PPD. The review shows that irremediability has been a central and recurring issue in this debate for over 20 years and that the arguments addressing it revolve around 3 main themes. First, whether uncertainty about irremediability can be sufficiently eliminated and how this influences the acceptability of PAD. Second, whether access to PAD introduces hopelessness in psychiatric patients and thereby contributes to irremediability. Third, whether patients who refuse certain treatments can be considered to be suffering irremediably.

Uncertainty

Absolute certainty about the prognosis of any psychiatric disorder is unreachable; psychiatry does not differ in this aspect from other medical fields. Although absolute certainty is impossible, knowledge about treatment options for individual patients can be improved. Precision psychiatry is promising in this respect. Machine learning algorithms, based on both clinical information and biomarkers, are increasingly capable of predicting treatment outcome.58 These relatively new research methods can be used to quantify the recovery chances for an individual patient with a seemingly irremediable psychiatric disorder. This will help patients and psychiatrists to make informed decisions about PAD. It might also foster the development of new palliative psychiatric approaches that may prevent PAD. The development of new methods to reduce uncertainty will, however, not solve the issue completely. Even if knowledge of possible treatment options increases, a certain level of uncertainty will remain. Unless the proposition is a total ban of PAD, it seems reasonable to direct attention to the level of uncertainty that is morally admissible and the due diligence procedures needed to establish this level. Various safeguards might be explored, such as mandatory second opinions by psychiatrists specialized in the patient’s disorder or mandatory time between the request and performance of PAD. Qualitative research among psychiatrists with experience in PAD can provide insights and suggestions for safeguards.

Hope

It has both been claimed that PAD can induce hopelessness and that it can resolve hopelessness. A reason to doubt that PAD induces hopelessness is the finding that psychotherapists do not induce suicidal thoughts by discussing suicide with a patient.59 Even more so, openly discussing suicidal ideation leads to better disease outcomes.59 One might argue that the option of PAD can have the same function: By discussing PAD openly, recovery may become possible. The effect of PAD of PPD on hope requires further empirical research. This can be performed through surveys using hopelessness scales or through qualitative interviews among psychiatric patients who request PAD, or in jurisdictions that do not allow PAD, among psychiatric patients who appear to suffer irremediably.60 Also interviewing patients who where granted PAD, but eventually choose against it, would be helpful in this respect. Such studies might help to better understand the phenomenon of hope in the context of discussing PAD with psychiatric patients. This may help psychiatrist to deal with expectations and experiences of patients. Yet, in individual cases, a clinical assessment of the reaction of the patient on the possibility of PAD in a jurisdiction will be needed, and the psychiatrist might require a second opinion and further deliberation with colleagues in order to come to a well-considered conclusion concerning the role of hope.

Treatment Refusal

Treatment refusal is a relevant issue in PAD of PPD since empirical research shows that in a considerable number of cases in which PAD was performed in PPD, the patient refused one or more treatment options. This raises questions concerning the relationship between refusal of treatment and irremediability of suffering. On the one hand, it can be argued that as long as treatment options exist, suffering is not irremediable. On the other hand, one can argue that demanding a patient to undergo different treatments for which he or she is not motivated may be ineffective and harmful, as motivation is an important determinant of treatment efficacy, especially when it concerns psychotherapy.61 Further empirical research on reasons underlying treatment refusal is needed. Also, the efficacy of treatments that psychiatric patients who request PAD have to “undergo” in order to satisfy the requirement of irremediable suffering should be studied. This review shows that different jurisdictions allowing PAD have different ways of handling treatment refusal; the question underlying these policies is as follows: Who has agency to decide whether enough treatments have been tried before PAD is justified? If this decision is left entirely to the patient, based on the respect for their autonomous choice, patients may choose to refuse all treatment in order to candidate for PAD. Alternatively, the decision can be left to the psychiatrist, which can be seen as unduly paternalistic. A third approach is to find a balance between these options through shared decision-making; this approach is laid down in the Dutch euthanasia law. Policy-making concerning how to deal with treatment refusal in the context of PAD of PDD will require both empirical information on effectiveness of treatments and reasons for refusal and normative considerations concerning the physician–patient relationship.62

Future Research

Our review shows that there is little empirical research available on psychiatric patients who request PAD. Until fairly recent, PAD of PPD was largely a theoretical issue, for it was only performed sporadically. The increase of PAD of PPD in certain jurisdictions offers an opportunity to further study this practice. Indeed, a few empirical studies have been performed (Table 1), but they have methodological shortcomings that are mentioned by the authors in the discussion paragraphs. The opportunity for thorough empirical studies on PAD of PPD is here now and should be used. When performing these empirical studies, researchers should not focus on “the psychiatric patient” as a single group but pay attention to differences between individual psychiatric disorders.

Strengths and Weaknesses

A strength of this review is that we performed a comprehensive and systematic study of the literature on irremediability in the context of PAD of PPD. A weakness is that the included empirical studies were of low quality; therefore, a critical appraisal of the evidence was of no added value, and the numbers mentioned should be carefully considered when used elsewhere.

Conclusion

Irremediability of suffering is an important aspect of any justification for PAD. Whether psychiatric suffering can and should be classified as irremediable has been an issue of debate for over 20 years. This systematic review showed that arguments about irremediability evolve around 3 main themes and provide suggestions for empirical research and normative deliberation. The first theme is uncertainty about irremediability. This calls for empirical research in order to diminish the level of uncertainty about irremediability as well as deliberation on what level of certainty is necessary for PAD of PDD to be acceptable. The second theme is hope. This calls for more research on the relationship between the option of PAD of PDD and the phenomenon of hope in patients and the need for deliberation in individual patient cases. The third theme concerns treatment refusal. This calls for further empirical investigation into which treatments are being refused, and why, and normative deliberation on the justification of decisions to forego treatment in the context of the physician–patient relationship. Finally, this review showed the lack of thorough empirical studies and basic epidemiological data on PPD who request and receive PAD.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental_material for Irremediable Psychiatric Suffering in the Context of Physician-assisted Death: A Scoping Review of Arguments by Sisco M. P. van Veen, Andrea M. Ruissen and Guy A. M. Widdershoven in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Sisco M. P. van Veen, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6660-8500

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6660-8500

Supplemental Material: The supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Verhofstadt M, Thienpont L, Peters GJY. When unbearable suffering incites psychiatric patients to request euthanasia: qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;211(4):238–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shaffer CS, Cook AN, Connolly DA. A conceptual framework for thinking about physician-assisted death for persons with a mental disorder. Psychol Public Policy Law. 2016;22(2):141–157. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dutch Regional Euthanasia Review Committee. Annual report. 2018. [accessed 2019 August 8]. https://english.euthanasiecommissie.nl/the-committees/annual-reports.

- 4. Dierickx S, Deliens L, Cohen J, Chambaere K. Euthanasia in Belgium: trends in reported cases between 2003 and 2013. CMAJ. 2016;188(16):E407–E414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Open Science Framework Preregistration. [accessed 2019 February 1]. https://osf.io/thjg8.

- 7. Zwakman M, Verberne LM, Kars MC, Hooft L, van Delden JJM, Spijker R. Introducing PALETTE: an iterative method for conducting a literature search for a review in palliative care. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim SYH, de Vries R, Peteet JR. Euthanasia and assisted suicide of patients with psychiatric disorders in the Netherlands 2011 to 2014. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(4):362–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schoevers RA, Asmus FP, Tilburg WV. Physician-assisted suicide in psychiatry: developments in the Netherlands. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(11):1475–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berghmans R. Commentary on “suicide, euthanasia, and the psychiatrist.” Philos Psychiatry Psychol. 1998;5(2):131–135. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burnside JW. Commentary on “suicide, euthanasia, and the psychiatrist.” Philos Psychiatry Psychol. 1998;5(2):8. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kissane DW, Kelly BJ. Demoralisation, depression and desire for death: problems with the Dutch guidelines for euthanasia of the mentally ill. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34:325–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kelly BD, McLoughlin DM. Euthanasia, assisted suicide and psychiatry: a pandora’s box. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:278–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Naudts K, Ducatelle C, Kovacs J, Laurens K, van den Eynde F, van Heeringen C. Euthanasia: the role of the psychiatrist. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;(188):405–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Appel JM. A suicide right for the mentally ill. Hastings Cent Rep. 2007;37(3):21–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lopez A, Yager J, Feinstein RE. Medical futility and psychiatry: palliative care and hospice care as a last resort in the treatment of refractory anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43(4):372–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vandenberghe J. The “good death” in the Flemish psychiatry [Dutch]. Tijdschr Psychiatr. 2011;53:551–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brown SM, Elliott CG, Paine R. Withdrawal of nonfutile life support after attempted suicide. Am J Bioeth. 2013;13(3):3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cowley C. Euthanasia in psychiatry can never be justified. A reply to Wijsbek. Theor Med Bioeth. 2013;34(3):227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berghmans R, Widdershoven G, Widdershoven-Heerding I. Physician-assisted suicide in psychiatry and loss of hope. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2013;36(5–6):436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schuklenk U, Vathorst SVD. Treatment-resistant major depressive disorder and assisted dying. J Med Ethics. 2015;41(8):577–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Broome MR, de Cates A. Choosing death in depression: a commentary on “treatment-resistant major depressive disorder and assisted dying.” J Med Ethics. 2015;41(8):586–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cowley C. Commentary on “treatment-resistant major depressive disorder and assisted dying.” J Med Ethics. 2015;41(8):585–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pienaar W. Developing the language of futility in psychiatry with care. South African J Psychiatry. 2016;22(1):978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim SYH, Lemmens T. Should assisted dying for psychiatric disorders be legalized in Canada? Can Med Assoc J. 2016;188(14):337–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Olié E, Courtet P. The controversial issue of euthanasia in patients with psychiatric illness. JAMA. 2016;316(6):656–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hodel MA, Trachsel M. Letter to the editor, in comment on euthanasia or assisted suicide in patients with psychiatric illness. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2153–2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blikshavn T, Husum TL, Magelssen M. Four reasons why assisted dying should not be offered for depression. J Bioeth Inq. 2017;14(1):151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Appelbaum PS. Should mental disorders be a basis for physician-assisted death? Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(4):315–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yarascavitch A. Assisted dying for mental disorders: why Canada’s legal approach raises serious concerns. J Ethics Ment Heal. 2017;10(2):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kirby J. Medical assistance in dying for suffering arising from mental health disorders: could augmented safeguards enhance its ethical acceptability? J Ethics Ment Health. 2017;10(1):5. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Steinbock B. Physician-assisted death and severe, treatment-resistant depression. Hastings Cent Rep. 2017;47(5):30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kelly BD. Invited commentary on “when unbearable suffering incites psychiatric patients to request euthanasia.” Br J Psychiatry. 2017;211(4):248–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reel K, Macri R, Dembo JS, et al. Assisted death in mental health: our last, best judgement In:Cooper DB, editor. Ethics in mental health-substance use. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2017. p. 293–314. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bay MJD. The devil is in the details: thoughts on medical aid in dying for persons with mental illness. J Ethics Ment Heal. 2017:10. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rooney W, Schuklenk U, van de Vathorst S. Are concerns about irremediableness, vulnerability, or competence sufficient to justify excluding all psychiatric patients from medical aid in dying? Heal Care Anal. 2017;26(4):326–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dembo J, Schuklenk U, Reggler J. . “For their own good”: a response to popular arguments against permitting medical assistance in dying (MAID) where mental illness is the sole underlying condition. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(7):451–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Simpson AIF. Medical assistance in dying and mental health: a legal, ethical, and clinical analysis. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(2):80–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Appelbaum PS. Physician-assisted death in psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(2):145–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Demyttenaere K, Van Duppen Z. The impact of (the concept of) treatment-resistant depression: an opinion review. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;22(2):85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. The Flemish Society of Psychiatry. Advisory text: how to handle a request for physician assisted death in psychiatry within the current legal framework. [Dutch]. 2017. [accessed 2019 April 8]. http://vvponline.be/uploads/docs/bib/euthanasie_finaal_vvp_1_dec.pdf.

- 42. Dutch Society of Psychiatry. Guideline for physician assisted death for patients with psychiatric disorders [Dutch]. 2018. [accessed 2018 November 1]. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/levensbeeindiging_op_verzoek_psychiatrie/startpagina_-_levensbe_indiging_op_verzoek.html.

- 43. Dutch Regional Euthanasia Review Committees. Euthanasia code 2018. [accessed 2019 July 11]. https://english.euthanasiecommissie.nl/.

- 44. Legemaate J, Gevers JKM. Physician-assisted suicide in psychiatry: developments in the Netherlands. Cambridge Q Healthc Ethics. 1997;6:175–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. de Boer AP, Oei TI. Assisted suicide in psychiatry; current situation and notes on a recent case [Dutch]. Tijdschr Psychiatr. 2011;53(8):543–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Walker-Renshaw B, Finley M, Carter V. Canada: will the supreme court of Canada’s decision on physician-assisted death apply to persons suffering from severe mental illness? J Ethics Ment Heal. 2015;1:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Downie J, Dembo J. Medical assistance in dying and mental illness under the new Canadian law. J Ethics Ment Heal. 2016;1:1. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Groenewoud JH, van der Maas PJ, van der Wal G, et al. Physician-assisted death in psychiatric practice in the Netherlands. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(25):1795–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Thienpont L, Verhofstadt M, Van Loon T, Distelmans W, Audenaert K, De Deyn PP. Euthanasia requests, procedures and outcomes for 100 Belgian patients suffering from psychiatric disorders: a retrospective, descriptive study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(7):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Legemaate J, van der Heide A, et al. Third evaluation report of the Dutch euthanasia law. [Dutch]. 2017. [accessed 2019 September 14]. https://publicaties.zonmw.nl/derde-evaluatie-wet-toetsing-levensbeeindiging-op-verzoek-en-hulp-bij-zelfdoding/.

- 51. van Veen SMP, Weerheim FW, Mostert M, van Delden JJM. Euthanasia of Dutch patients with psychiatric disorders between 2015 and 2017. J Ethics Ment Heal. 2018;10:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tuffrey-Wijne I, Curfs L, Finlay I, et al. Euthanasia and assisted suicide for people with an intellectual disability and/or autism spectrum disorder: an examination of nine relevant euthanasia cases in the Netherlands (2012-2016). BMC Med Ethics. 2018;19(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nicolini ME, Peteet JR, Donovan GK, Kim SYH. Euthanasia and assisted suicide of persons with psychiatric disorders: the challenge of personality disorders. Psychol Med. 2019;1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Appelbaum PS. Physician-assisted death for patients with mental disorders—reasons for concern. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(4):325–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Miller FG. Treatment-resistant major depressive disorder and assisted dying (response). J Med Ethics. 2015;41(8):577–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chabot BE. The request for physician assisted suicide [Dutch]. Tijdschr Psychiatr. 2000;42:759–766. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tholen AJ, Berghmans RL, Legemaate J, Nolen WA, Huisman J, Scherders MJ. Physician assisted suicide of patients with a psychiatric disorder: guidelines for psychiatrists [Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1999;143(17):905–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chekroud AM, Zotti RJ, Shehzad Z, et al. Cross-trial prediction of treatment outcome in depression: a machine learning approach. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dazzi T, Gribble R, Wessely S, Fear NT. Does asking about suicide and related behaviours induce suicidal ideation? What is the evidence? Psychol Med. 2014;44(16):3361–3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: the hopelessness scale. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1974;42(6):861–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ryan RM, Lynch MF, Vansteenkiste M, Deci EL. Motivation and autonomy in counseling, psychotherapy, and behavior change: a look at theory and practice. Couns Psychol. 2011;39(2):193–260. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Emanuel EJ. Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1992;267(16):2221–2226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental_material for Irremediable Psychiatric Suffering in the Context of Physician-assisted Death: A Scoping Review of Arguments by Sisco M. P. van Veen, Andrea M. Ruissen and Guy A. M. Widdershoven in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry