Abstract

Objective:

The American University of Beirut Faculty of Medicine follows the American model of medical education. In 2013-2014, a carefully designed new curriculum replaced the previous, largely traditional curriculum, and aimed to improve student wellbeing, upgrade the learning environment, enhance student empathy, and counter the negative influences of the hidden curriculum. This longitudinal study assessed the effectiveness of the new curriculum in those domains over a period of 7 years.

Methods:

Three cohorts of medical students anonymously filled a paper-based survey at the end of years 1, 2, 3, and 4 of the 4-year curriculum. These included the Class of 2016, the last batch of students who followed the old curriculum, and 2 cohorts that followed the new curriculum (Class of 2017 and Class of 2019). The perceived learning environment was assessed by the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measurement survey; the student’s empathy was assessed by the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy-Student version; and the hidden curriculum was examined using a locally developed survey.

Results:

The scores on the learning environment survey were significantly higher among the cohorts following the new curriculum relative to those following the old curriculum. Similar significant results appeared when looking at each of the subscales for the learning environment. The students’ empathy scores were also significantly higher in both cohorts of the new curriculum when compared with the old curriculum. Nevertheless, there was a significant decrease in empathy in both third and fourth years relative to second year. The new curriculum also improved aspects of the students’ perceptions and responses to the hidden curriculum.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, a well-planned and well-researched curricular intervention, based on sound educational theories, practices, and standards can indeed transform the learning environment, as well as the attitudes, values, and experiences of medical students.

Keywords: Curriculum, learning environment, empathy, hidden curriculum

Introduction

Undergraduate medical education has witnessed major transformations over the last few decades. These include an emphasis on horizontal and vertical integration, student-centeredness, problem solving, development of competence, and expansion of instruction into non-traditional and non-scientific domains that address the students’ attitudes, behaviors, and skills.1,2

The Faculty of Medicine at the American University of Beirut (AUBFM), established in 1867, follows the American model of medical education, and uses English as the language of instruction. In 2013-2014, after 4 years of intensive preparation, we implemented a new curriculum starting with Year 1 of medical school. The process was informed by the medical education literature and current standards of education adopted by major medical education bodies, particularly the AAMC/LCME.3 The previous curriculum had been largely traditional: a first year devoted to normal structure and function and essentially discipline based, and a second year that focused on pathology and pathophysiology in an organ-system based approach, and with isolated pharmacology, microbiology and physical diagnosis courses. Both years were heavily didactic and focused on the science of medicine, with little if any attention to topics and disciplines like ethics, humanism, professionalism, communication skills, and personal development. It was teacher centered, norm-referenced, and the assessment was largely summative. Students complained of the lack of integration of topics both within the basic sciences and between basic and clinical medicine, the heavy schedule, the emphasis on short-term memorization, and the fierce competitiveness among them, which created a negative environment for learning. In addition we realized that this curriculum was no longer fulfilling the needs and goals of a modern medical education, by neglecting the non-scientific and non-cognitive aspects of the students’ development.

The new curriculum, which we named the Impact curriculum, adopted this new paradigm in medical education, and this was reflected in its vision to graduate physicians who are “healers, scholars, educators and advocates.” In order to achieve that vision, we initially focused on the pre-clerkship curriculum (the first 2 years) and introduced the following innovations:

Integrated organ system modules instead of discipline based courses: the purpose of this was to foster depth of understanding of the content, reveal the relevance of the material to the students’ overall goal of becoming physicians, and unveil the multidisciplinary nature of medicine.

A series of 4 courses entitled Physicians Patients and Society that ran through the 4 years of medical school. These covered the medical humanities (such as art, literature, and history of medicine), medical ethics, the psychology of illness, spirituality and medicine, and palliative care, among other topics. It included patient and nurse shadowing sessions. The ultimate goals of these courses were to enhance student empathy, compassion, and professionalism.

Two courses labeled Learning Communities, where a small group of students met with a faculty preceptor periodically and longitudinally over 2 years to discuss topics relevant to their development as both human beings and professionals. These topics included learning through reflection, time management, conflict management, personal beliefs and internal struggles, teamwork, giving and receiving feedback, burnout and emotional intelligence among others. The sessions provided a venue for students to share experiences and concerns and seek support from peers and faculty in a safe, non-judgmental environment. The faculty mentors, who got to know the students well, doubled as their advisors.

A Social Medicine and Global Health course in year 1 that touched on social, political, cultural, and economic factors that influence the practice of medicine, and aimed to develop advocacy for patient and community health among students. This was followed by a community-oriented group research project in year 2.

We introduced 2 courses in years 1 and 2 to develop the clinical and communication skills of students, which relied heavily on real and simulated patients and simulation equipment for practice and feedback, thus allowing the students to learn and make errors in a safe environment under direct supervision. These courses also emphasized the principles of ethics and empathy that were conveyed in other courses.

We decreased didactic teaching in favor of team-based problem-solving exercises and student-centered learning. Students spent several weeks working with the same team of peers across courses to solve exercises relevant to what they were learning. This strategy aimed to enhance their communication skills, teamwork, collaborative spirit, and professionalism.

We changed the grading system in the first 2 years from a norm-based, relative grading system with 4 levels of achievement (Excellent, Good, Pass, Fail) to a Pass/Fail, criterion-based grading system. The aim of this change was primarily to engender a culture of assessment for, rather than of, learning, thus decreasing unhealthy competitiveness among them while enhancing their internal motivation and ensuring achievement of competence.

We believed that these innovations would improve the learning environment for the students and their ability to eventually navigate through the complex clinical environment (mainly in years 3 and 4). In fact, in designing this curriculum, we always had in mind the hidden curriculum of the medical school4 which would most impact students in the clinical years of the program, and many of the above interventions and courses were meant to prepare them to face and resist any negative impact of the hidden curriculum, by enhancing their empathy, compassion, values, sensibility, and awareness.

In parallel with the preparations for the curriculum, we developed a plan to test its efficacy using multiple approaches and tools, the results of some of which have been reported already.5 In addition to regular course and instructor evaluations, periodic town-hall meetings, periodic small group focus groups, and utilization of standardized tests of knowledge (ie, NBME subject and customized exams), we specifically assessed the ability of this well-studied and deliberate change to effect change in 3 important parameters we wanted to target and believed we could influence as described above: the students’ learning environment, their level of empathy, and their perception of the hidden curriculum. In this study we report outcomes in these 3 domains.

Methods

Participants

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the AUBFM, and all participants signed an informed consent.

We followed 3 cohorts of medical students at AUBFM longitudinally. These students were invited to anonymously fill a paper-based survey at the end of years 1, 2, 3, and 4 of the 4-year medical curriculum. These cohorts included the last batch of medical students who followed the old curriculum (Class of 2016), and 2 cohorts that followed the Impact curriculum (Classes of 2017 and 2019) (Supplemental Figure S1). We followed the Class of 2017 because it was the first to follow the new curriculum, and the Class of 2019 in order to evaluate the situation 2 years later, at a time when the curriculum became relatively well established. At this time, there was much less monitoring and intervention with the students than for the Class of 2017. Thus, we purposefully included the Class of 2019 because we wanted to ascertain that any beneficial effects of the new curriculum would be sustained beyond the first year of implementation, knowing that the first implementation of curricular change is accompanied by extra care that could positively influence the students’ impressions of the curriculum and environment, thus affecting the results.

Measurements

The paper-based self-administered survey consisted of 4 parts. Following a question on their current stage in medical school, it asked the participants to develop a personal, unique 8-letter code; this was used to follow the students’ responses over time while maintaining their anonymity. Next, students were asked to fill 3 questionnaires relating to the learning environment, their level of empathy, and the hidden curriculum.

The learning environment

The learning environment was assessed by the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measurement (DREEM). This is a 50-item validated tool that is culturally non-specific, developed for the assessment of the learning environment of students in the healthcare profession. DREEM is composed of 5 subscales: perception of learning, perception of teachers, academic self-perception, perception of atmosphere, and social self-perception, using a 5-point Likert scale. The maximum possible score on the DREEM questionnaire is 200.6,7 Scores on the DREEM questionnaire are interpreted according to the following guideline: 0 to 50 (very poor), 50 to 100 (plenty of problems), 101 to 150 (more positive than negative), and 151 to 200 (excellent).

Student’s empathy

The student’s empathy level was assessed by the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy-Student version (JSPE-S), a 20-item validated tool designed to reflect students’ orientation or attitudes toward empathy in the context of caregiver-care receiver relationship.8,9 It uses a 7-point Likert scale with a maximum possible score of 140. There is no specific guide for the interpretation of scores other than a higher score indicating a higher level of empathy. Permission to use copies was secured from the Jefferson Medical College.

Hidden curriculum

Due to the absence of a validated scale, we developed a set of questions based on qualitative studies that attempted to assess students’ perception of the hidden curriculum.10-13 The questions were enhanced and checked for face and content validity by a number of volunteer medical students as well as members of the Program of Research and Innovation in Medical Education (PRIME), an expert panel on medical education at AUBFM.

The questionnaire was comprised of 29 questions that reflected aspects of the hidden curriculum that we were interested in exploring within the students’ learning and training environment. These addressed their perceptions of the several issues relating to professional behavior of their peers and seniors, including presumed role models, the prevailing attitudes and behaviors toward patients, the values of the institution, the treatment, assessment and judgment of students at the institution and, in general, the relationships among people within the institution. These were developed based on 4 general constructs relating to the hidden curriculum: (1) professionalism (questions 19, 26, 27, 28, and 29); (2) values (questions 1, 3, 6, 8, 12, 16, 17, 20, and 23); (3) attitudes to and treatment of patients (questions 4, 9, 13, 21, 24 and 25); and (4) attitudes to and treatment of students (questions 2, 5, 7, 10, 11, 14, 15, 18, and 22). Students had to indicate their level of agreement with various statements using a Likert scale, ranging from a score of 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). We configured and analyzed the questionnaire such that the higher the score, the better the perception of the hidden curriculum. The maximal possible score was 116.

The hidden curriculum scale was pilot-tested with 140 students from the 4 classes enrolled at AUBFM in 2013 (Supplemental Figure S1).

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into SPSS version 22 (IBM, NY, USA) and presented as graphs or tables as appropriate.

For the learning environment, the total score of the DREEM scale was calculated by adding the responses to all 50 items after transforming the negatively worded questions. The scores on the 5 DREEM subscales were also calculated according to previously reported guidelines.7 Surveys with more than 20% missing data (ie, >10 items) were excluded from analysis; otherwise the missing numbers were replaced by the value of 2 which is the code for “uncertain.” As for the students’ empathy score, it was calculated by adding the responses to all 20 items after transforming the negatively worded questions (as per the developer’s instructions). Surveys with more than 20% missing data (ie, >4 items) were excluded from analysis; otherwise the missing values were replaced by the average response of the individual.9

Concerning the hidden curriculum scale, the total score was also calculated by adding the responses to all 29 items after transforming the negatively worded questions. Surveys with more than 7 items missing were excluded from analysis; otherwise the missing numbers were replaced by the value of 2 which is the code for “uncertain.”

Cronbach’s alphas were computed for assessment of reliability of the 3 instruments by including data from the 3 longitudinal cohorts. Notably, and for the purpose of instrument validation, Cronbach’s alpha was also calculated to check for internal consistency of the hidden curriculum questionnaire with the respondents of the cross sectional pilot testing cohort. In addition, and in order to test for concurrent criterion validity, bivariate Pearson correlation analysis was performed between the learning environment and hidden curriculum also including data from the 3 longitudinal cohorts.

The mean scores ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of the 3 scales were then compared using 2-way ANOVA for the whole cohort, one factor being Class and the other being Medical School Year. We also used ANOVA with repeated measures to compare the scores of students in the 3 classes who repeatedly filled the questionnaires over the 4 years. The results of the interactions between Class and Medical School Year are depicted as line plots with P-values. In addition, the independent curriculum or class effect on the 3 scales including the 5 learning environment subscales are depicted as graphs and supplementary tables, including post hoc least significant difference (LSD). Because the hidden curriculum questionnaire was novel, responses to each of the 29 individual questions were compared by curriculum stage using 1-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc LSD. A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participants

The response rates for the survey, at different times and for different classes, ranged from as low as 16% (Year 1 Class of 2016) to as high as 78% (Year 2, Class of 2019) (Supplemental Table S1). The number of surveys that were included in the different analyses was frequently lower, however, due to incomplete filling of all surveys by some of the students. For the hidden curriculum questionnaire, most of the missing data were related to the last 3 questions, which asked whether the student had witnessed unprofessional behavior among nurses, residents, and clinicians. This was particularly the case among students from the pre-clerkship years (Years 1 and 2), who had minimal encounters with these groups of individuals. As for the analysis using repeated measures ANOVA, the numbers were quite low because several students either did not complete the survey at each of the 4 time-points or chose not to include their unique code (Supplemental Table S2).

Internal consistency of the 3 scales

The 3 scales showed very good to excellent internal consistency with Cronbach’s alphas of 0.993, 0.877, and 0.839 for the learning environment, students’ empathy and hidden curriculum, respectively.

The pilot study for the hidden curriculum (27 Medicine 1, 26 Medicine 2, 33 Medicine 3, and 54 Medicine 54), also showed a relatively high Cronbach’s alpha of 0.851.

In addition, there was a positive correlation between the scores on the hidden curriculum and those on the learning environment, with a Pearson correlation of 0.613 (P < .0001) (Supplemental Figure S2).

Effect of the new curriculum on the learning environment

Two way analysis of variance revealed a near significant interaction of Medical School Year and Class on the learning environment scores (P = .054), such that the Class of 2016 scores started out lower than the other 2 classes and increased slightly in years 3 and 4, while for the other 2 classes, the scores remained the same over the 4 years (Figure 1a). There was an obvious difference in scores among classes in the repeated measures analysis, where the Class of 2016 had consistently lower scores over the 4 years relative to the 2 other classes (Figure 1b), though the trend over time did not differ among the 3 classes.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the learning environment (a and b), students’ empathy (c and d), and hidden curriculum (e and f) by Class and Medical School Year of the 4-year curriculum.

Two-way ANOVA for the whole cohort and repeated measures ANOVA for students’ with repeated measures, with each of the scales as dependent variables and class and medical school year as independent variables. P values on the figures are for the interaction of the 2 factors. The effects of each factor alone are depicted in Figures 2 and 3.

Focusing on the effect of the Class factor (ie, reflecting the effect of the curricular change), and confirming the above observation, the learning environment scores were significantly higher in the 2 classes that followed the new curriculum (Classes of 2017 and 2019), compared with the Class of 2016 (P < .0001), with the Class of 2017 also having higher scores than the Class of 2019 (Figure 2a, Supplemental Table S3). This difference between old and new curriculum was clearer when the analysis was restricted to repeated measurements (Figure 2b, Supplemental Table S4), where the scores for the Classes of 2017 and 2019 were similar and much higher than those for the Class of 2016. These differences were reproduced when the analysis was focused on the individual subscales of the learning environment (perception of learning, perception of teachers, academic self-perception, perception of atmosphere, and social self-perception) using 2-way ANOVA (Supplemental Tables S5 and S6).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the learning environment (a and b), students’ empathy (c and d), and hidden curriculum (e and f) by Class.

Two-way ANOVA for the whole cohort and repeated measures ANOVA for students’ with repeated measures.

Post hoc least significant difference (LSD) analysis was used to compare any 2 classes: *P ⩽ .05, **P ⩽ .01.

As for the effect of Medical School Year, there were no significant differences in the learning environment scores among the 4 years of medical school (Figure 3a with Supplemental Table S7 and Figure 3b with Supplemental Table S8). Among the subscales of the learning environment, only academic self-perception was significantly higher in the clinical years (Medicine 3 and 4) when compared to the preclinical years (Medicine 1 and 2) in both the full cohort (Supplemental Table S9) and among students with repeated measures (Supplemental Table S10).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the learning environment (a and b), students’ empathy (c and d) and hidden curriculum (e and f) by Medical School Year of the 4-year curriculum.

Two-way ANOVA for the whole cohort and repeated measures ANOVA for students’ with repeated measures.

Post hoc least significant difference (LSD) analysis was used to compare any 2 years: *P ⩽ .05, **P ⩽ .01.

Effect of the new curriculum on the students’ empathy scores

Similar to the findings in the learning environment, there was no significant interaction of Class and Medical School Year on the empathy scores of students (Figure 1c and d). However, group analysis showed that the Classes of 2017 and 2019 had higher scores on the empathy scale when compared to the Class of 2016; this was observed in both the whole cohort (Figure 2c and Supplemental Table S3) and in those with repeated measurements over the 4 years (Figure 2d and Supplemental Table S4).

Interestingly, when looking at the effect of Medical School Year for the whole cohort, empathy scores were significantly higher in Year 2 compared with Years 1, 3, and 4 (Figure 3c and Supplemental Table S7). Analysis using repeated measures confirmed the lower scores in Years 3 and 4 relative to both Years 1 and 2, with Year 2 scores remaining higher than year 1 scores (Figure 3d and Supplemental Table S8).

Effect of the new curriculum on the hidden curriculum

Looking at the results of the whole cohort, there was no significant interaction between Class and Medical School Year on the hidden curriculum scores—with the curves almost superimposed (Figure 1e and Supplemental Table S3). There was no significant effect of Class within the whole cohort (Figure 2e), but there was an effect of Medical School Year, such that scores of Year 4 students were significantly lower than those of Year 1 and Year 2 students (Figure 3e).

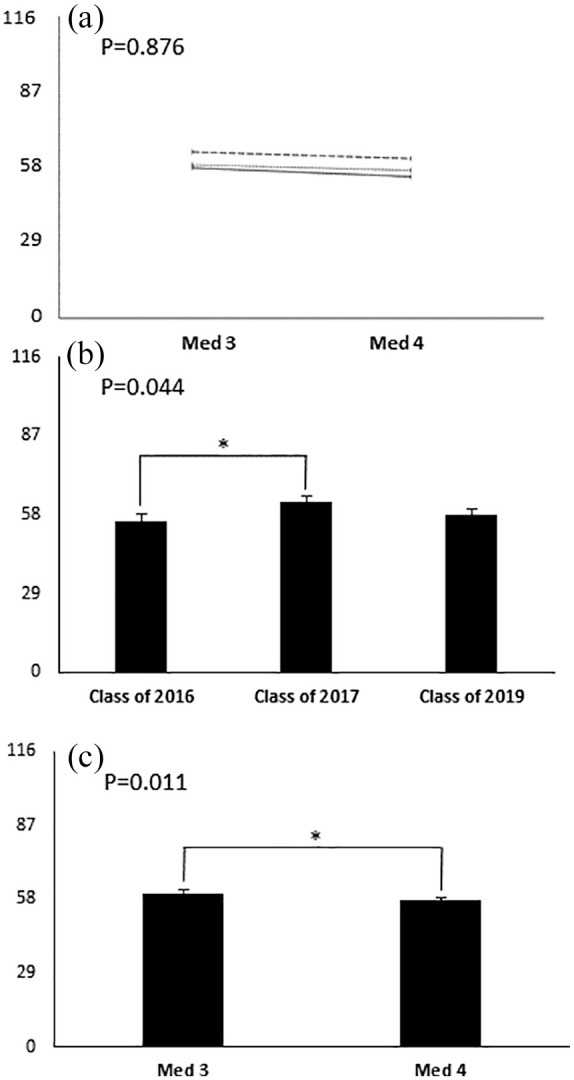

Repeated measures ANOVA suggested that Class of 2019 had higher scores than both Classes of 2017 and 2016 (Figures 1f and 2f). Unfortunately, this analysis was unreliable as the numbers were very small with only 1, 6, and 5 individuals having repeated scores in the Classes of 2016, 2017, and 2019, respectively (Supplemental Tables S2 and S4). Restricting the repeated measures analysis to Years 3 and 4, we obtained a significantly higher score for the Class of 2017 relative to both Class of 2016 and Class of 2019 (Figure 4a and b), and we obtained a significant drop from Year 3 to Year 4 for all classes (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the hidden curriculum for only Med 3 and Med 4 students with repeated measures with (a) showing the interaction between class and year, (b) showing the effect of Class alone, and (c) showing the effect of Medial School Year alone.

Repeated measures ANOVA with each of the scales as dependent variables and class and medical school year as independent variables.

P value on Figure 4a is for the interaction of the 2 factors.

P value on Figure 4b is for the effect of medical school year. *P ⩽ .05, **P ⩽ .01 with post hoc least significant difference (LSD).

P value on Figure 4c is for the effect of class.

Analysis of the individual questions of the hidden curriculum scale revealed specific differences among classes (Supplemental Table S11). Both Classes of 2017 and 2019 agreed less than Class of 2016 with the statements that the system promotes fierce competitiveness and that students are judged primarily according to their grades (Q15 and 17). They also tended to agree, more than Class of 2016, that relationships are governed by collegiality (Q6), that their values have not been compromised during their training (Q16), that faculty support them when they try to legitimize patient concerns (Q22), and that faculty at AUBMC respect their patients (Q24). On the other hand, Class of 2019 students, specifically, appeared to have witnessed more unprofessional behavior among nurses, residents and faculty (Q27-29) than Classes of 2016 and 2017. They also believed that patients tend to get dehumanized at AUBMC (Q21), and cared about what patients think about them (Q23), more so than both other classes. Curiously, Class of 2017 students agreed more than Class of 2016 that they had to do something improper to fit in, whereas Class of 2019 students agreed less with this statement (Q8). Similarly, Class of 2016 felt more intimidated by their seniors than students in both Classes of 2016 and 2019 (Q10).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that a carefully designed medical curriculum, with interventions specifically designed to achieve specific objectives, based on sound educational theory and accepted pedagogical standards, can achieve the desired outcomes. In this particular study, these outcomes included improvement in all aspects of the learning environment, enhancement of student empathy, and a better preparation of students for their encounter with the hidden curriculum.

The learning environment

It was clear that the overall learning environment improved significantly following the implementation of the new curriculum. This encompassed all 5 aspects of the environment, including the students’ perceptions of learning, of teachers, and atmosphere, and their academic and social self-perception.

Items in the students’ perception of learning and academic self perception section of the survey address issues such as student-centeredness of the curriculum, degree of active learning, degree of focus, extent of student participation, and how stimulating the material is, as well as confidence of the students about passing and about their preparation, development of their problem solving skills, and relevance of the material to the medical profession. We believe that the integration of the basic and clinical sciences, the inclusion of extensive problem solving, team based learning sessions that allow interaction among students and faculty and enhance timely feedback, and the institution of clear criterion-based standards for pass/fail contributed significantly to the improvement of the students’ perceptions of their learning and their academic self-perception.

The teachers under the new curriculum were essentially the same as those under the old curriculum; however, the students’ perception of teachers improved. The relevant sections in the DREEM included items addressing the teachers’ knowledge, their communication skills, patient centeredness, attitude, provision of feedback, and preparation for sessions, among others. This finding is interesting and may relate to the fact that under the new curriculum, the teachers had to assume new roles besides lecturing. These included clinical skills training, mentoring on professional and personal development, coverage of new content (eg, humanities and social medicine) and running, extensively, team-based, interactive, problem based sessions.

In addition, we believe that the novel curricular interventions increased the motivation of students and allowed them to concentrate on learning and actually enjoy it more than in the old curriculum—issues reflected in the higher score on their perceptions of the atmosphere.

The emphasis on group work, the provision of mentors within the Learning Communities courses, which addressed issues relevant to student development and daily life, and the decrease in fierce competitiveness resulting from the elimination of a graded and ranking system, likely alleviated stress, reduced burnout, and provided for a good support system, thus improving the students’ social self-perception.

Finally, it is interesting to note that the improved perception of the learning environment started in Year 1 and persisted till Year 4, even though most of the curricular interventions were directed at Years 1 and 2, suggesting a lasting effect on student attitudes and perceptions.

Empathy

Some of the new courses we developed for the curriculum (and others that were reconfigured) specifically aimed to enhance the students’ empathy, compassion, and advocacy. These were the Physicians Patients and Society courses and the Social Medicine and Global Health course. The Learning Communities and Clinical Skills courses also helped in this direction. We were happy to see higher empathy scores for the students who followed the Impact curriculum. We ascribe these changes to modules in the medical humanities such as literature and medicine, art and medicine, and history of medicine, and others such as the psychology of illness, palliative care, and spirituality and medicine, all of which emphasized the understanding of the patient’s perspective, interpreting their verbal and non-verbal expressions, and dealing with suffering and death. In addition, several students indicated that having them shadow an underprivileged outpatient presenting to the medical center from the time of arrival till departure, then writing a reflective piece on that extended encounter, was an enlightening and shaping experience for them.

In this context, it is interesting to note that following implementation of the Impact curriculum, our school witnessed a significant increase in student-led humanitarian initiatives and voluntarism, dedicated to underprivileged and marginalized communities such as refugees, domestic and migrant workers, and the poor in general. These individual efforts eventually coalesced into ABMCares, an organization comprised of students, faculty and administration officials that aims to provide “healthcare services to marginalized, vulnerable, and underserved populations in Lebanon” (see https://www.aub.edu.lb/fm/Pages/AUBMCares.aspx). HEAL is one example of the projects under the umbrella of AUBMCares, being a “student-run free clinic that aims to provide free primary health care services to the medically underserved migrant workers in Beirut.”

There was a decrease in empathy scores during the clinical clerkship years irrespective of the class or curriculum, which is consistent with earlier reports.14,15 We did not find a difference among the 3 classes over time, possibly because of the very small numbers of data points in the repeated measures analysis, but it looked like the Class of 2016 sustained a greater decrease (Figure 1d).

The hidden curriculum

The students’ perceptions of the hidden curriculum were assessed by a locally generated questionnaire. The questionnaire was validated in 3 ways: (1) It was developed by the authors based on their collective experiences in the institution, and the medical education literature that defined aspects of the hidden curriculum; the questionnaire was then reviewed and modified by a panel of experts in medical education together with input from students; (2) the reliability of its scores was quite high with a Cronbach alpha of 0.83; (3) there was significant correlation between the hidden curriculum survey scores and those on the DREEM questionnaire, which assesses the learning environment as whole, many aspects of which relate to the hidden curriculum.

There was essentially no difference in the perceptions of the hidden curriculum among the 3 classes over time. Nonetheless, the clinical years (Years 3 and 4) are characterized by a more prominent hidden curriculum, marking the students’ transition from the more structured and controlled classroom-based education and simulated environment, to the more chaotic clinical practice realm. The results demonstrate that the Class of 2017 had a better perception of the hidden curriculum during their clinical years compared to the other classes (Figure 4), suggesting some effect of the Impact curriculum. Similarly, the perception of the hidden curriculum deteriorated when students reached Years 3 and 4, the clinical years, with a notable additional decline from Year 3 to Year 4. This suggests that the more time students spend in the clinical environment, the more they grapple with the negative influence of the hidden curriculum.

Focusing on individual items in the survey reveals interesting insights. Indeed, most of the significant differences here were observed for the Class of 2019 rather than the Class of 2017, particularly in relation to witnessing unprofessional behavior, perceiving that patients are getting dehumanized, caring about what patients think, not compromising their values and not acting simply to fit in or in fear of bad evaluations. This suggests that these students have gained some “resistance” to the negative effects of the hidden curriculum or have acquired greater sensibility, sensitivity and awareness of it. The reason this was not observed or achieved for the Class of 2017 is elusive, but conceivably, it may have taken a few years and successive classes following the new curriculum in order for the concepts, values, and attitudes spread through the Impact curriculum to become accepted and effective within the student culture and environment in our institution.

Limitations

This study is limited by the fact that the results that we describe cannot be easily attributed to specific changes or modifications that were made, but rather to the general curricular reform process as a whole. Notably, we were keenly aware that the Class of 2017 did receive extra care, and the positive results may relate to that. For instance, this class was very closely monitored by the faculty and the administration, and there were frequent interventions and communication with the students on matters relating to the curriculum, its aims and rationale, and to the students’ attitudes, behavior, learning approaches, opinions and feedback, etc. This level of follow-up was markedly reduced in later classes, once we were comfortable that the curriculum moved along smoothly. That is precisely why we included the Class of 2019—at which time the level of intervention and follow-up was reduced to what we consider a stable level. The study also suffers from variable sample sizes at different collection time points and for different classes, especially for the repeated measures analyses; this fact renders the comparisons difficult to interpret.

Conclusion

Based on the results of our study and our experience over 7 years, we believe that a well-planned, well-researched curricular intervention, based on sound educational theories, practices, and standards, can indeed achieve the desired outcomes, and can effect a lasting transformation in the attitudes, values, and experiences of medical students.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank members of the Program for Research and Innovation in Medical Education (PRIME) at AUBFM, all AUBFM instructors and course coordinators for their continuous efforts in medical education innovations, and AUBFM medical students.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: American University of Beirut, Center for Teaching and Learning Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (CTL-SOTL) grant.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: NKZ, ZD, and RS were involved in the conceptualization and design of the study, and acquisition of data. They conducted all data analysis, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and completed multiple rounds of revision based on feedback from all authors. TA and KFB contributed to study design, interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved and renewed yearly by the Institutional Review Board of the American University of Beirut (Pharmaco.NZ.18).

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376:1923-1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Voelker R. AMA, AAMC say reform needed across continuum of US medical education. JAMA. 2005;294:416-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Association of American Medical Colleges and American Medical Association. Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and structure of a medical school. Standards for accreditation of medical education programs leading to the MD degree. https://rfums-bigtree.s3.amazonaws.com/files/resources/2019-20-functions-and-structure.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed March 14, 2019.

- 4. Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998;73:403-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zgheib N, Dimassi Z, Bouakl I, Badr K, Sabra R. The long-term impact of team based learning on medical students’ team performance scores and on their peer evaluation scores. Med Teach. 2016;23:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roff S. The Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM)—a generic instrument for measuring students’ perceptions of undergraduate health professions curricula. Med Teach. 2005;27:322-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McAleer S, Roff S. A practical guide to using the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM). AMEE Medical Education Guide 2001;23:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasiri J, Cohen MJM, Gonella JS, Erdmann J. The Jefferson scale of physician empathy: development and preliminary psychometric data. Educ Psychol Meas. 2001;61:349-365. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thomas Jefferson University Center for Research in Medical Education and Health Care. Jefferson scales of empathy (JSE). https://www.jefferson.edu/university/skmc/research/research-medical-education/jefferson-scale-of-empathy.html. Published 2012. Accessed June 20, 2013.

- 10. Murakami M, Kawabata H, Maezawa M. The perception of the hidden curriculum on medical education: an exploratory study. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2009;8:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lempp H, Seale C. The hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: qualitative study of medical students’ perceptions of teaching. BMJ. 2004;329:770-773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Billings ME, Lazarus ME, Wenrich M, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA. The effect of the hidden curriculum on resident burnout and cynicism. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3:503-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gaufberg EH, Batalden M, Sands R, Bell SK. The hidden curriculum: what can we learn from third-year medical student narrative reflections? Acad Med. 2010;85:1709-1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, et al. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med. 2009;84:1182-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Neumann M, Edelhäuser F, Tauschel D, et al. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2011;86:996-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]