Abstract

Aim:

To determine the minimum number of optical coherence tomography B-scan corrections required to provide acceptable vessel density measurements on optical coherence tomography angiography images in eyes with diabetic macular edema.

Methods:

In this prospective, noninterventional case series, the optical coherence tomography angiography images of eyes with center-involving diabetic macular edema were assessed. Optical coherence tomography angiography imaging was performed using RTVue Avanti spectral-domain optical coherence tomography system with the AngioVue software (V.2017.1.0.151; Optovue, Fremont, CA, USA). Segmentation error was recorded and manually corrected in the inner retinal layers in the central foveal, 100th and 200th optical coherence tomography B-scans. The segmentation error correction was then continued until all optical coherence tomography B-scans in whole en face image were corrected. At each step, the manual correction of each optical coherence tomography B-scan was propagated to whole image. The vessel density and retinal thickness were recorded at baseline and after each optical coherence tomography B-scan correction.

Results:

A total of 36 eyes of 26 patients were included. To achieve full segmentation error correction in whole en face image, an average of 1.72 ± 1.81 and 5.57 ± 3.87 B-scans was corrected in inner plexiform layer and outer plexiform layer, respectively. The change in the vessel density measurements after complete segmentation error correction was statistically significant after inner plexiform layer correction. However, no statistically significant change in vessel density was found after manual correction of the outer plexiform layer. The vessel density measurements were statistically significantly different after single central foveal B-scan correction of inner plexiform layer compared with the baseline measurements (p = 0.03); however, it remained unchanged after further segmentation corrections of inner plexiform layer.

Conclusion:

Multiple optical coherence tomography B-scans should be manually corrected to address segmentation error in whole images of en face optical coherence tomography angiography in eyes with diabetic macular edema. Correction of central foveal B-scan provides the most significant change in vessel density measurements in eyes with diabetic macular edema.

Keywords: artifact, diabetic macular edema, optical coherence tomography angiography, segmentation error, vessel density

Background

Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) is a noninvasive imaging modality that provides three-dimensional depth-resolved images from retinal, choroidal, and optic nerve head circulation.1 Previous studies have shown the ability of OCTA to show posterior segment microvascular pathologies including retinal and choroidal vascular disorders and optic neuropathies.2–4

OCTA images are created by analyzing the difference between sequential OCT B-scans. Correct identification of the retinal and choroidal layers is essential in providing accurate measurements. Several studies have shown that misidentification of the retinal layers, also known as segmentation error, is a major source of error in OCT measurements.5–7 Although previous studies have reported different types of artifacts in OCTA images,8–12 limited studies have shown the impact of segmentation error on OCTA quantitative measurements.13,14 Our group has shown that segmentation error and consequent vessel density (VD) measurement error occurred in all eyes with diabetic macular edema (DME), and in one-third of healthy eyes.13 Therefore, manual correction of segmentation error is a crucial part of OCTA imaging studies.

Manual correction of all segmentation errors in an OCTA image is a difficult and time-consuming procedure. For example, a skilled technician should correct around 300 OCT B-scans for a single image of a patient with DME. Recent advances in OCTA software allow automated propagation of manual segmentation correction of an OCT B-scan to adjacent B-scans. The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of manual correction of segmentation error on OCTA metrics in eyes with DME and to determine the minimum required OCT B-scan corrections to provide acceptable VD measurements.

Methods

This study was a prospective, noninterventional case series on patients with center-involving DME, who underwent OCTA. The study was approved by the Iran University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee and adhered to the tenets of Declaration of Helsinki. Eyes with any ocular pathology other than diabetic retinopathy such as vitreomacular interface abnormalities (except for mild epiretinal membrane), and choroidal neovascularization were excluded. Eyes with spherical equivalent refraction of more than 3.5 diopters of myopia or hyperopia were excluded.

OCTA imaging was performed using RTVue Avanti spectral-domain OCT system with the AngioVue software (V.2017.1.0.151; Optovue, Fremont, CA, USA). En face 3 × 3 OCTA images were acquired from the fovea. Images with a scan quality of <5 and those with motion artifact were excluded.

The superficial capillary plexus (SCP) and deep capillary plexus (DCP) en face images were automatically segmented by the device software. SCP was segmented with an inner boundary set at the internal limiting membrane (ILM) and an outer boundary set at 9 μm above the inner plexiform layer (IPL). The DCP en face image was segmented with an inner boundary 9 μm above the IPL and an outer boundary at 9 μm below the outer plexiform layer (OPL). The vascular density of the fovea (central 1 mm of the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) grid) and parafovea (500–1500 μm from the foveal center), in the SCP and DCP, that was automatically generated by the instrument, was recorded. Also, the central subfield thickness, the superficial inner retinal thickness in the central subfield (ILM to 9 μm above the IPL), and the deep inner retinal thickness in the central subfield (9 μm above the IPL to 9 μm below the OPL) were recorded. The method of segmentation correction was described elsewhere.13 One expert graders (S.G.) evaluated the segmentation lines of the SCP and DCP (ILM, IPL, OPL, and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)) in the registered horizontal OCT B-scan, respectively, and recorded the number of B-scans with segmentation error in each layer in the whole image, between the 100th and 200th, 0–100th and 200–304th B-scans. If the segmentation lines were not correctly aligned according to the parameters defined above, the ‘Edit Bnd/Propagation’ tool on the device software was used for manual correction. This tool automatically applies the manually corrected segmentation to the registered OCT B-scan and propagates the correction to the adjacent B-scans. The segmentation correction was started from inner layers (ILM to OPL) on a single B-scan in the central fovea, and propagation function was used to automatically spread the correction to other B-scans in the whole image. Then, the upper and lower OCT B-scans were reviewed to find any uncorrected segmentation error. Segmentation corrections were continued by the graders for the 200th and 100th OCT B-scans, respectively, and then throughout other OCT B-scans, if necessary, until all OCT B-scans were corrected in the whole image (Figure 1). In some eyes, the segmentation error in OPL could not be completely corrected and further correction resulted in more segmentation error in other B-scans. Therefore, full correction was considered when the final segmentation correction of OPL was successful in ⩾95% of B-scans. OCTA images with final segmentation correction of OPL <95% were excluded. The VDs in the SCP and DCP, and retinal thicknesses were recorded before and after each segmentation error correction by first grader. The segmentation boundaries were evaluated separately by a senior grader (R.M.) and any discrepancy was resolved by open discussion.

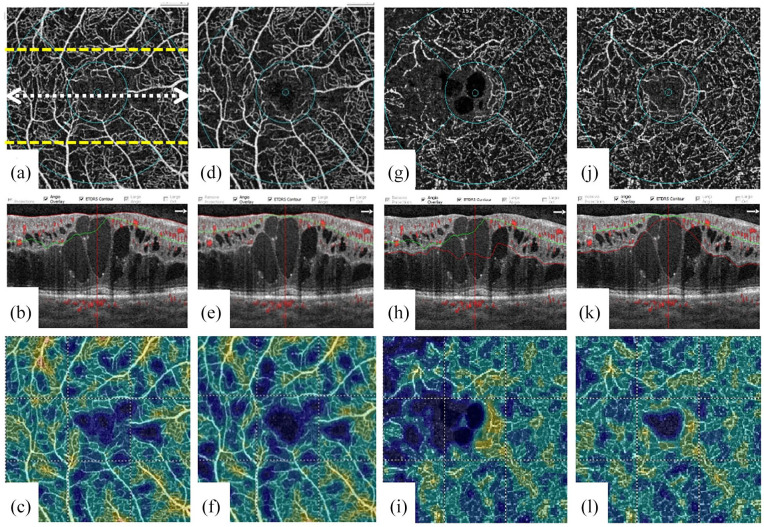

Figure 1.

En face optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA), OCTA B-scan, and vessel density image of a patient with diabetic macular edema before [(a–c) for superficial capillary plexus and (g–i) for deep capillary plexus] and after [(d-f) for superficial capillary plexus and (j-l) for deep capillary plexus] segmentation error correction at the level of inner plexiform layer. The double arrow line shows the location of the corresponding OCT B-scan at the foveal center. Upper and lower dashed lines show 100th and 200th OCT B-scan locations.

The data were entered using a SPSS software (V.15.0. SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The changes were calculated by subtracting the post-error correction values from the baseline measurements and the absolute changes were calculated by ignoring the negative signs, to determine the actual magnitude of the changes without regard to their signs. DME was categorized based on the OCT patterns into the four groups: diffuse macular edema, diffuse macular edema with cystoids changes, diffuse macular edema with subretinal fluid, and diffuse macular edema with cystoids spaces and subretinal fluid.15 Mixed model and repeated measures analyses were used. Considering inclusion of bilateral cases, inter-eye correlation was considered in the analysis. Post hoc analysis was performed using least significant difference test. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Thirty-six eyes of 26 patients with center-involving DME with a mean ± standard deviation (SD) age of 57.64 ± 10.24 were included. Regarding the pattern of macular edema, 55.6% (20 eyes) had diffuse edema with cystic changes, 36.1% (13 eyes) had diffuse edema with cysts and subretinal fluid, 5.6% (2 eyes) had diffuse edema alone, and 1 eye (2.7%) had diffuse edema with subretinal fluid. Mean central subfield thickness of retina was 578.17 ± 156.75 µm.

There was no segmentation error at the RPE and ILM in any of eyes. At baseline, the automated segmentation of IPL and OPL layers was correct in 7 (19.4%) and 2 (5.6%) eyes, respectively. However, correct automated segmentation of both IPL and OPL layers was found in only one eye (2.7%).

Mean number of OCT B-scans that needed correction to achieve correct segmentation in whole image was 1.72 ± 1.81 (range: 0–7) and 5.57 ± 3.87 (range: 0–18) for IPL and OPL, respectively. Table 1 shows the number of eyes with segmentation error at different OCT B-scans. The main location for segmentation error was fovea (between 100th and 200th B-scans).

Table 1.

Number of Eyes With At Least One OCT B-Scan Segmentation Error and the Percentages of OCT B-Scans With Segmentation Error at Baseline.

| Layer | Number of eyes (%) with segmentation error | % of B-scans with segmentation error |

|---|---|---|

| IPL in whole image | 29 (80.6%) | 49.74 ± 38.99 |

| IPL at the foveal center B-scan | 25 (69.4%) | NA |

| IPL between 100th to 200th B-scan | 29 (80.6%) | 65.47 ± 39.30 |

| IPL between 0th and 100th B-scan | 18 (50%) | 42.25 ± 47.32 |

| IPL between 200th and 304th B-scan | 21 (58.3%) | 41.50 ± 45.82 |

| OPL in whole image | 34 (94.4%) | 49.31 ± 27.39 |

| OPL at the foveal center B-scan | 31 (86.1%) | NA |

| OPL between 100th and 200th B-scan | 34 (94.4%) | 78.25 ± 30.18 |

| OPL between 0th and 100th B-scan | 25 (69.4%) | 32.17 ± 35.44 |

| OPL between 200th and 304th B-scan | 26 (72.2%) | 37.53 ± 36.31 |

IPL, inner plexiform layer; NA, not applicable; OPL, outer plexiform layer.

After correction and propagation of the IPL segmentation error at the single central foveal B-scan, the IPL was corrected automatically at all other OCT B-scans in 17 (58.6%) of 29 eyes that needed IPL correction. In remaining 12 eyes, additional correction was needed at 100th B-scans (two eyes) and 200th B-scan (three eyes) and other B-scans (12 eyes). After correction and propagation of the OPL segmentation error at the single central foveal B-scan, OPL was completely corrected in whole image in only two eyes (5.8%) of 35 eyes that needed OPL correction. Sixteen eyes (44.4%) and 17 eyes (47.2%) needed OPL correction at 200th and 100th B-scan, respectively; however, 30 of 35 eyes (85.7%) needed further corrections in other B-scans as well.

The mean absolute change in VD after complete segmentation error correction was 1.31 ± 1.69% (range: 0–6.2%) and 3.00 ± 4.06% (range: 0–15.8%) for SCP and DCP, respectively. A change in VD of more than 4.5% was found in 11 eyes (30.5%). In repeated measures analysis, the changes in whole image VD at SCP was not statistically significantly different during different stages of segmentation correction at IPL and OPL layers (p = 0.2 and p = 0.3, respectively). However, there was a statistically significant difference in foveal VD at SCP after IPL correction (p = 0.001). The changes in whole image VD measured at DCP was statistically significantly different after correction of IPL (p = 0.001). In post hoc analysis, the VD at DCP was statistically significantly different after single foveal B-scan correction of IPL compared with the baseline measurements (p = 0.03); however, it remained statistically unchanged after further segmentation corrections of IPL. Foveal VD measurement changes at DCP were not significantly different (p = 0.54); however, the parafoveal VD measurements at the DCP were statistically significantly different after IPL correction (p = 0.01). The changes in VD of DCP after correction of OPL were not statistically significant (p = 0.51). The details of VD measurements are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Vessel Density Measurements Before and After Different Stages of Segmentation Error Correction.

| Stage of correction | Whole image VD at SCP | p a | Foveal VD at SCP | p a | Parafoveal VD at SCP | p a | Whole image VD at DCP | p a | Foveal VD at DCP | p a | Parafoveal VD at DCP | p a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 38.50 ± 5.31 | Ref. | 21.22 ± 6.16 | Ref. | 39.51 ± 5.98 | Ref. | 38.62 ± 5.71 | Ref. | 27.35 ± 9.35 | Ref. | 39.96 ± 5.90 | Ref. |

| After IPL correction of single foveal B-scan | 38.10 ± 5.03 | 0.24 | 19.71 ± 4.52 | 0.03 | 39.57 ± 5.67 | 0.85 | 37.01 ± 4.74 | 0.03 | 26.21 ± 7.20 | 0.35 | 38.42 ± 5.01 | 0.038 |

| After IPL correction of 200th B-scan | 38.13 ± 5.24 | 0.28 | 19.87 ± 4.56 | 0.05 | 39.65 ± 5.78 | 0.67 | 36.96 ± 4.69 | 0.02 | 26.18 ± 7.28 | 0.34 | 38.37 ± 4.95 | 0.031 |

| After IPL correction of 100th B-scan | 38.10 ± 5.20 | 0.24 | 19.76 ± 4.51 | 0.03 | 39.62 ± 5.74 | 0.73 | 37.01 ± 4.74 | 0.03 | 26.36 ± 7.23 | 0.42 | 38.41 ± 4.99 | 0.036 |

| IPL fully corrected | 38.10 ± 5.08 | 0.24 | 19.48 ± 4.49 | 0.01 | 39.06 ± 6.88 | 0.48 | 37.08 ± 4.72 | 0.04 | 26.21 ± 7.65 | 0.36 | 38.44 ± 4.96 | 0.040 |

| p valueb | 0.27 | 0.001 | 0.63 | 0.001 | 0.54 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Before OPL correction | 38.10 ± 5.08 | Ref. | 19.48 ± 4.49 | Ref. | 39.06 ± 6.88 | Ref. | 37.08 ± 4.72 | Ref. | 26.21 ± 7.65 | Ref. | 38.44 ± 4.96 | Ref. |

| After OPL correction of single foveal B-scan | 38.21 ± 5.08 | 0.53 | 19.53 ± 4.52 | 0.11 | 39.06 ± 6.88 | 0.76 | 37.44 ± 4.56 | 0.23 | 25.89 ± 7.33 | 0.54 | 38.61 ± 4.88 | 0.534 |

| After OPL correction of 200th B-scan | 38.21 ± 5.08 | 0.53 | 19.52 ± 4.54 | 0.25 | 39.01 ± 6.95 | 0.16 | 37.24 ± 4.65 | 0.61 | 0.17 | 38.04 ± 5.21 | 0.100 | |

| After OPL correction of 100th B-scan | 38.20 ± 5.07 | 0.10 | 19.53 ± 4.52 | 0.07 | 39.06 ± 6.88 | 0.74 | 36.81 ± 5.12 | 0.43 | 26.75 ± 7.25 | 0.78 | 38.20 ± 5.47 | 0.404 |

| OPL fully corrected | 38.21 ± 5.05 | 0.10 | 19.33 ± 4.66 | 0.43 | 39.44 ± 5.61 | 0.52 | 37.12 ± 5.51 | 0.94 | 26.38 ± 6.94 | 0.83 | 38.02 ± 5.64 | 0.223 |

| p valueb | 0.34 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.26 | 0.23 | ||||||

DCP, deep capillary plexus; IPL, inner plexiform layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; SCP, superficial capillary plexus; VD, vessel density.

Post hoc analysis comparing with baseline measurements (Ref.).

Repeated measures analysis.

The mean superficial inner retinal thickness at the central subfield was 98.14 ± 86.62 µm at baseline and 64.03 ± 17.49 µm after final correction of IPL (p = 0.011). There was a statistically significant difference after single foveal correction of IPL (65.36 ± 17.29 µm, p = 0.02). No statistically significant change was found after correction of IPL at 200th and 100th B-scan (p = 0.423 and p = 0.334, respectively). The mean deep inner retinal thickness was 140.44 ± 92.66 µm at baseline and 148.78 ± 106.01 µm after final OPL correction (p = 0.33).

Discussion

In this study, automated segmentation of the OCTA software failed to properly segment the boundaries of the inner retinal layers in 97% of eyes with DME and manual correction of the segmentation error resulted in significant change in VD measurements. After segmentation error correction, a change in VD of >4.5%, which is considered clinically important,16 was found in 30% of eyes. Our results are in line with previous studies that showed that manual correction of segmentation error significantly impacts the OCTA derived measurements.13,14

Misidentification of retinal boundaries is a common finding in OCT images obtained from healthy and pathologic eyes and the impact of segmentation error correction has already been shown for retinal thickness measurements.6,17 However, manual delineation of retinal boundaries on all OCT B-scans that comprise the volume dataset is time-consuming and not feasible in a clinical settings.18 Previous studies have shown that B-scan density can be reduced in volume OCT acquisitions with minimal change in retinal thickness measurements.19–21 In these studies, retinal thickness maps were generated using less dense subsets of scans by removing other B-scans. To our knowledge, no study investigated the minimum number of OCT B-scans that should be corrected without removing other B-scans to produce similar thickness map in eyes with segmentation errors. OCTA software utilizes the OCT data to provide the angiographic image. Therefore, it is rational to investigate the minimum number of OCT B-scans that need manual correction of the segmentation.

This study shows that OPL needs more attempts for segmentation correction (mean of 5.57 ± 3.87/eye) than IPL (mean of 1.72 ± 1.81/eye) to achieve correct segmentation in whole image. Segmentation error occurred mainly in the fovea (between B-scans number 100 and 200). After manual correction of the foveal central B-scan and propagation to whole image, additional B-scan corrections were needed in other parts of the image in 41% of eyes for IPL and 94% of eyes for OPL. These rates remained nearly the same after manual correction and propagation of the B-scans number 100 and 200. The change in VD measurements was statistically significant after IPL correction; however, no statistically significant change was found after OPL correction. Interestingly, maximum change in VD measurements occurred after first IPL correction (i.e. at the foveal center), and then remained stable. The retinal thickness measurement changes followed the same pattern after segmentation error correction. If confirmed in future larger studies, it may be concluded that by IPL correction at the foveal center, valid VD measurements are obtained for clinical use. However, the segmentation error should be fully corrected in clinical trials when the OCTA metrics are main outcome measures.

This study has some limitations. The sample size is small and there is no control group of healthy eyes and eyes with other retinal and choroidal pathologies. However, in our previous study, the rate of segmentation error and the changes in VD measurements after manual correction was negligible; therefore, we did not include healthy eyes in this study.13 Also, in some eyes, the segmentation correction could not be completed in all B-scans at the level of OPL. Therefore, we considered a cut-off of at least 95% of final correct segmentation. In addition, this study was performed with a single device and its specific software (AngioVue). Other devices may be different based on their segmentation and propagation algorithm. Despite these imitations, our study shows that misidentification of retinal layers is a frequent artifact in macular OCTA images of patients with DME leading to significant error in VD measurements. Manual correction of segmentation of the retinal boundaries should be performed prior to extraction and analysis of OCTA metrics. Further studies with larger sample size and control group of patients with different retinochoroidal pathologies are warranted.

Conclusion

Propagation and correction of segmentation error in central foveal B-scan of OCTA images of patients with DME seems to be sufficient in daily clinical practice to obtain valid VD measurements.

Acknowledgments

All the authors included in this paper fulfill the criteria of authorship. K.G.F. contributed to writing the article, concept and design; data collection; analysis and interpretation; critical revision of the article; final approval of the article; provision of materials, patients or resources; and literature search. R.M., S.G., and M.S. contributed to writing the article; analysis and interpretation; data collection; and provision of materials.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval and consent to participate: The study was approved by the Iran University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (IR.IUMS. REC.1398.078) and adhered to the tenets of Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was supported by a grant from Iran University of Medical Sciences (No. 98-1-26-14567).

ORCID iDs: Khalil Ghasemi Falavarjani  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5221-1844

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5221-1844

Reza Mirshahi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5997-6417

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5997-6417

Shahriar Ghasemizadeh  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1567-1280

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1567-1280

Availability of data and materials: The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Contributor Information

Khalil Ghasemi Falavarjani, Eye Research Center, The Five Senses Institute, Rassoul Akram Hospital, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Reza Mirshahi, Eye Research Center, The Five Senses Institute, Rassoul Akram Hospital, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Sattarkhan-Niaiesh St, Tehran, 1445613131, Iran.

Shahriar Ghasemizadeh, Eye Research Center, The Five Senses Institute, Rassoul Akram Hospital, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Mahsa Sardarinia, Eye Research Center, The Five Senses Institute, Rassoul Akram Hospital, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

References

- 1. Falavarjani KG, Sarraf D. Optical coherence tomography angiography of the retina and choroid; current applications and future directions. J Curr Ophthalmol 2017; 29: 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akil H, Falavarjani KG, Sadda SR, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography of the optic disc; An overview. J Ophthal Vision Res 2017; 12: 98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khadamy J, Abri Aghdam K, Falavarjani K. An update on optical coherence tomography angiography in diabetic retinopathy. J Ophthal Vision Res 2018; 13: 487–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chalam KV, Sambhav K. Optical coherence tomography angiography in retinal diseases. J Ophthal Vision Res 2016; 11: 84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Han IC, Jaffe GJ. Evaluation of artifacts associated with macular spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology 2010; 117: 1177–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sadda SR, Wu Z, Walsh AC, et al. Errors in retinal thickness measurements obtained by optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology 2006; 113: 285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alshareef RA, Dumpala S, Rapole S, et al. Prevalence and distribution of segmentation errors in macular ganglion cell analysis of healthy eyes using Cirrus HD-OCT. PLoS ONE 2016; 11:e0155319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Spaide RF, Fujimoto JG, Waheed NK. Image artifacts in Optical coherence tomography angiography. Retina 2015; 35: 2163–2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Al-Sheikh M, Ghasemi Falavarjani K, Akil H, et al. Impact of image quality on OCT angiography based quantitative measurements. Int J Retina Vitreous 2017; 3: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ghasemi Falavarjani K, Al-Sheikh M, Akil H, et al. Image artefacts in swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography. Br J Ophthalmol 2017; 101: 564–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Spaide RF, Curcio CA. Evaluation of segmentation of the superficial and deep vascular layers of the retina by optical coherence tomography angiography instruments in normal eyes. JAMA Ophthalmol 2017; 135: 259–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Enders C, Lang GE, Dreyhaupt J, et al. Quantity and quality of image artifacts in optical coherence tomography angiography. PLoS ONE 2019; 14:e0210505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ghasemi Falavarjani K, Habibi A, Anvari P, et al. Effect of segmentation error correction on optical coherence tomography angiography measurements in healthy subjects and diabetic macular oedema. Br J Ophthalmol 2020; 104: 162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rommel F, Siegfried F, Kurz M, et al. Impact of correct anatomical slab segmentation on foveal avascular zone measurements by optical coherence tomography angiography in healthy adults. J Curr Ophthalmol 2018; 30: 156–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim BY, Smith SD, Kaiser PK. Optical coherence tomographic patterns of diabetic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol 2006; 142: 405.e1–412e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Czakó C, Sándor G, Ecsedy M, et al. Intrasession and between-visit variability of retinal vessel density values measured with OCT angiography in diabetic patients. Sci Rep 2018; 8:10598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Waldstein SM, Gerendas BS, Montuoro A, et al. Quantitative comparison of macular segmentation performance using identical retinal regions across multiple spectral-domain optical coherence tomography instruments. Br J Ophthalmol 2015; 99: 794–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koleva-Georgieva DN. Optical coherence tomography—segmentation performance and retinal thickness measurement errors. Eur Ophthalmic Rev 2012; 6: 78. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sadda SR, Keane PA, Ouyang Y, et al. Impact of scanning density on measurements from spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010; 51: 1071–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Velaga SB, Nittala MG, Konduru RK, et al. Impact of optical coherence tomography scanning density on quantitative analyses in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Eye (Lond) 2017; 31: 53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chhablani J, Barteselli G, Bartsch DU, et al. Influence of scanning density on macular choroidal volume measurement using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2013; 251: 1303–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]