Abstract

Background

This study builds on previous successes of using tracer indicators in tracking progress towards Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and complements them by offering a more detailed tool that would allow us to identify potential process barriers and enablers towards such progress.

Purpose

This tool was designed accounting for possibly available data in low- and middle-income counties.

Methodology

A systematic review of relevant studies was carried out using PubMed, ISI Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, and ProQuest databases with no time restriction. The search was complemented by a scoping review of grey literature, using the World Bank and the World Health Organization (WHO) official reports depositories. Next, an inductive content analysis identified determinants influencing the progress towards UHC and its relevant indicators. The conceptual proximity between indicators and categorized themes was explored through three focus group discussion with 18 experts in UHC. Finally, a comprehensive list of indicators was converted into an assessment tool and refined following three consecutive expert panel discussions and two rounds of email surveys.

Results

A total of 416 themes (including indicators and determinants factors) were extracted from 166 eligible articles and documents. Based on conceptual proximity, the number of factors was reduced to 119. These were grouped into eight domains: social infrastructure and social sustainability, financial and economic infrastructures, population health status, service delivery, coverage, stewardship/governance, and global movements. The final assessment tool included 20 identified subcategories and 88 relevant indicators.

Conclusion

Identified factors in progress towards UHC are interrelated. The developed tool can be adapted and used in whole or in part in any country. Periodical use of the tool is recommended to understand potential factors that impede or advance progress towards UHC.

Keywords: universal health coverage, health system, tool development, assessment tool

Introduction

The primary purpose of any healthcare system is to promote, restore and/or maintain the health of the population.1,2 Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is a means by which a healthcare system can reach this goal.1,3 UHC means that all individuals and communities receive the health services they need without suffering financial hardship.4,5 UHC ensures financial risk protection and gives everyone access to essential and quality health services.6,7

The effort to achieve UHC arises from the World Health Organization (WHO) Constitution of 1948, which declared health a fundamental human right.4,8 In 2005, WHO members signed a resolution encouraging countries to plan and pursue the transition of their health systems towards UHC.9,10 The 2008 and 2010, WHO reports emphasized population coverage, service coverage, and cost coverage as three dimensions of UHC.11–13 The 2012 United Nations resolution called governments to move towards providing affordable health services.14,15 WHO, World Bank, and other international agencies recommend UHC as the best strategy to achieve health-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) relevant to all countries.4

Despite financial and infrastructural challenges16,17 (ie, the unequal distribution of resources,13,18 fragmented risk pools,19 financial20,21 and political crises17,22), some middle-income countries (eg, Turkey and Thailand) have managed resources appropriately to achieve UHC.13,20 The duration of a transition period starting from a first policy intervention in the health insurance and financing sector to a first policy intervention aimed at UHC significantly varies by country. For example, in Australia, Japan, Germany, and Korea, this transition period lasted 79, 36, 127, and 26 years, respectively.23 To achieve UHC, high-income countries used different financing strategies and models, as well as various payment mechanisms. For example, the Netherlands24 and Singapore25 used a two-tier payment system; Japan,26 Norway,27 and Finland28 have implemented a single-payer system, while Germany,29 Austria,30 South Korea,31 and Switzerland32 have established a system of compulsory insurance. In countries such as Turkey,33 China,34,35 Thailand,36,37 Mexico,38,39 and South Korea,34 several fundamental reforms were implemented to increase the efficiency of respective healthcare systems on the path to achieve UHC.40,41 Some low- and middle-income countries, such as Ghana, China, Chile, Kyrgyzstan and Tanzania have made progress in achieving UHC in a number of areas but continue to face certain challenges in others (eg, level and expansion coverage; cost escalation, including total health expenditures and annual growth of medical expenditures; and lack of comprehensive health planning).

Significant efforts were made by the WHO and the World Bank Group to identify suitable UHC tracer indicators to measure progress towards UHC, for example, by using the UHC service coverage index (based on 16 tracer indicators of service coverage).5,42–45 Recent comprehensive assessment of UHC in 111 countries using this index showed that it is fairly stable across alternative calculations and that strong UHC performance is related to the share of a country’s health budget that is channeled through social health insurance schemes and government.44 Another study that estimated the health-related SDG index46 underscored the importance of increased collection and analysis of disaggregated data and highlighted where more deliberate targeting and design of interventions could accelerate progress in attaining the SDGs. Some other practical applications of tracking progress towards UHC include monitoring equity in UHC with essential services for neglected tropical diseases,5,43 using health service coverage index,47,48 or focusing on the effective coverage and delineating of three components of the metrics – need, use, and quality.49

A study conducted in Iran already tested a smaller set of tracer indicators in accordance with national and global goals and priorities, even though it was predominantly focused on monitoring and evaluation framework of the most recent healthcare reform (Health Transformation Plan).50

To achieve UHC, each country should create and adapt an effective framework of measuring and monitoring their progress of UHC. However, it is also essential to understand which factors impede or advance such progress towards UHC. This study builds on previous successes of using tracer indicators in tracking progress towards UHC and complements them by offering a more comprehensive tool that could allow us to identify potential process barriers and enablers and analyze them over time. When developing this tool, we also accounted for possibly readily available data in low- and middle-income countries.

Methods

The study was conducted in three phases: (1) a systematic literature review of relevant studies supplemented by a review of grey literature; (2) a content analysis to identify factors; and (3) refining and finalizing the tool through expert panels followed by email surveys.

Phase 1: Systematic Literature Review

A systematic literature review was carried out following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) protocol.

Search Strategy

We searched the following databases: PubMed, ISI Web of Science, EMBASE, Scopus, ProQuest, and Science Direct. WHO and World Bank databases that host reports related to UHC were also searched. The key search terms included “universal health coverage”, “universal coverage”, “universal healthcare coverage”, “universal health care coverage” and “UHC” combined with “OR” boolean in title or abstract (Table 1). Reference tracking was used to extract additional relevant studies based on citations of the eligible articles and documents.

Table 1.

Complete Search Strategy for PubMed Databases

| Set | Strategy | Results |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | “universal health care coverage”[Title/Abstract] OR “universal healthcare coverage”[Title/Abstract] OR “universal health coverage”[Title/Abstract] OR “universal coverage”[Title/Abstract] OR “UHC”[Title/Abstract] | 4423 |

| Health [Title/Abstract] | 1901551 | |

| #2 | “affecting factors”[Title/Abstract] OR “factors”[Title/Abstract] | 2048145 |

| #3 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 | 556* |

Note: *Filters activated: Publication date from 2000 to 2019, English, Persian.

Study Inclusion and Selection

There were no time restrictions. The publication language was restricted to English. All study reports, including review and original articles that describe the factors affecting UHC and related indicators, were included in the study. The letters to the editor and perspectives were not considered unless they had addressed a naive theme relevant to the study objectives. Abstracts of papers presented at seminars and conferences without the peer review process were not considered. Studies were included if they explored at least one objective around UHC, including financial protection, population coverage, and quality service coverage. All retrieved studies were screened against the inclusion criterion by two independent authors (ND and LD). Disagreements were resolved via discussion until the mutual agreement was achieved. Whenever it was not possible, a third author (AA) helped with reaching the consensus.

Data Extraction and Management

The validity of the tabulated data was evaluated by experts. Indicators that were used to monitor progress towards UHC were considered as the main data. The number and date of publication, type of publication, authors’ name and affiliation, the country where the study has been conducted, and any mentioning of UHC determinants (barriers and enablers) were considered as well. Extracted information was registered in a pre-designed form for every single study. A list of relevant factors and relevant indicators was arrayed as the output of this phase.

Phase 2: Content Analysis

Inductive content analysis was used for identifying conceptually approximate indicators and categorize extracted themes.51,52 Qualitative content analysis is a flexible data analysis method that can be used in systematic qualitative reviews. In this analysis, the researchers without any coding framework in mind began a review with few preconceptions about the topic. The analysis process was started by studying the findings and making evidence-based inferences about organizing codes.

Coding and categorizing were done by two researchers (ND and LD) using the following steps:53

Familiarization with data (reading selected studies);

Generating themes (identifying and extracting the UHC determinants (ie, barriers and enablers) from selected studies);

Classifying extracted effective determinants into subcategories and categories based on content relationship and conceptual proximity;

Reviewing themes and generating a thematic “map”;

Generating refined and clear definitions for subcategories and categories.

The result of conceptualization and categorization was refined through research team meetings. The link between determinants (identified themes and indicators) was discussed. Specified categories of the determinant factors of the progress towards the UHC were arranged through several research meetings. Results formed a draft of a tool used during the next phase.

Phase 3: Experts Opinion

The draft version of the tool was shared with 13 international experts in health systems and health policy for feedback. An expert panel, including 14 local Iranian experts in UHC, reviewed and discussed the content (as well as the face validity) of the tool. The meeting of the expert panel was conducted in one session and lasted around 2 h. The opinions of experts were recorded using a digital audio recorder, transcribed verbatim, and used by the research team to select, add, remove, and categorize indicators. Additional comments were obtained through an email survey. Participants of this survey included experts working in Health Care Management (five people), Health Policy (three people), and Health Economics (two people). All experts involved in the study were asked to fill out an informed consent form to participate in the focus group discussion and email survey.

Results

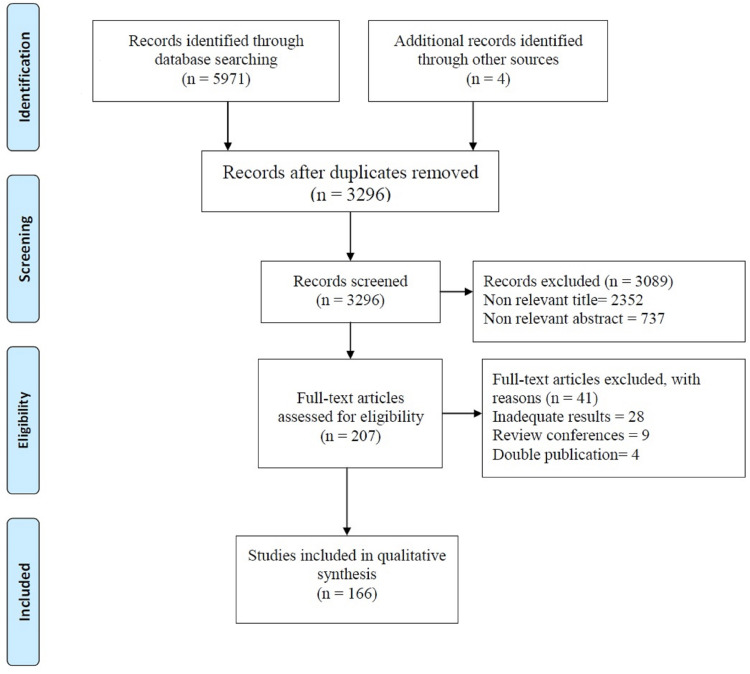

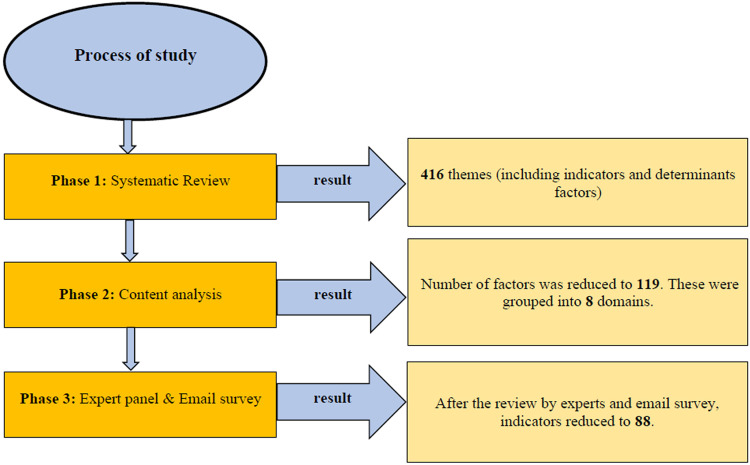

Of 5971 retrieved articles, 207 were eligible for full-text screening. Of them, 166 articles had relevant information (Figure 1 and Appendix 1) and were included in the final analysis. We identified 416 factors and grouped them into eight categories with 20 subcategories (Table 2 & Figure 2). Based on extracted data, the content analysis identified 88 indicators that fell within eight dimensions that assessed particular aspects of the healthcare system’s progress towards UHC. This included possible dimensions, axes, indicators titles, indicators definition, data collection methods, data collection sources, and formulae (Appendix 2). Based on experts’ opinion, dimensions and their relevant indicators were finalized as outlined below.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the searches and Inclusion process.

Table 2.

Dimensions and Axes of the Country’s Assessment Tool to Achieve Universal Health Coverage

| Dimensions | Axes | Indicators | Rate or (%) | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension 1 and 2- Social Infrastructure & Social Sustainability | Age Group | 1. Percent of population who ages 0–5 years | ||

| 2. Percent of population who ages 6–17 years | ||||

| 3. Percent of population who ages 18–39 years | ||||

| 4. Percent of population who ages 40–64years | ||||

| 5. Percent of population who ages 65 years or older | ||||

| Population | 6. Total population (pop.) | |||

| 7. Population growth rate (%) | ||||

| 8. Economically active pop. | ||||

| 9. Population employed in the informal sector economically (%) | ||||

| 10. Population employed in the formal sector economically (%) | ||||

| Literacy and Education | 11. Children Reaching Grade 5 of Primary Education | |||

| 12. Adult Secondary Education Achievement Level | ||||

| 13. Adult Literacy Rate | ||||

| Poverty | 14. Unemployment Rate | |||

| 15. Percent of Population Living below the Poverty Line | ||||

| 16. Gini Index of Income Inequality | ||||

| Dimension 3- Financial and Economic Infrastructures | GDP trends | 17. GDP per capita | ||

| 18. GDP growth rate | ||||

| 19. GDP adjusted | ||||

| Currency | 20. National currency unit | |||

| 21. Exchange rate US$ | ||||

| Health Expenditure Statistics | 22. Total health expenditure (THE) | |||

| 23. Total health expenditure (THE) as % of GDP | ||||

| 24. THE per capita (p.c.) in US$ (exchange rate) | ||||

| 25. General govt. health expenditure as % of GGE | ||||

| 26. General govt. health expenditure as % of THE | ||||

| 27. General govt. health expenditure (GGHE) p.c. (USD) | ||||

| 28. Out-of-pocket expenditure (OOP) per capita | ||||

| 29. OOP expenditure as % of THE | ||||

| 30. General govt. expenditure as % of GDP | ||||

| 31. Social security funds for health as % of GGHE | ||||

| 32. Private insurance as % THE | ||||

| 33. Private health expenditure as % of THE | ||||

| 34. Supplemental insurance as (%) of total health expenditures | ||||

| 35. Fairness in Financial Contribution Index (FFCI) | ||||

| 36. Incidence of catastrophic health expenditure due to OOP payments | ||||

| 37. Incidence of impoverishment due to OOP payments | ||||

| 38. Poverty gap due to OOP payments | ||||

| 39. Average per capita household income of income quintiles in total national income | ||||

| 40. Investment Share in GDP | ||||

| 41. Balance of Trade in Goods and Services | ||||

| 42. Debt to GDP Ratio | ||||

| Dimension 4- population health status | -Mortality -Morbidity |

43. Life expectancy at birth | ||

| 44. Healthy life expectancy (HALE) at birth | ||||

| 45. Probability of dying per 1 000 population between 15 and 60 years (adult mortality rate) | ||||

| 46. Probability of dying per 1 000 live births under 5 years (under-5 mortality rate) | ||||

| 47. Neonatal mortality rate (per 1 000 live births) | ||||

| 48. Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births) | ||||

| 49. Cause-specific mortality rate (per 100 000 population): HIV/AIDS | ||||

| 50. Cause-specific mortality rate (per 100 000 population): Tuberculosis | ||||

| 51. Age-standardized mortality rate by cause (per 100 000 population) | ||||

| 52. Years of life lost (YLLs) by broader causes | ||||

| 53. Causes of death among children under-5 years of age | ||||

| 54. HIV prevalence among adults (15–49) | ||||

| 55. Tuberculosis prevalence (per 100 000 population) | ||||

| 56. Tuberculosis incidence (per 100 000 population) | ||||

| 57. Number of confirmed poliomyelitis cases | ||||

| Dimension 5- Service Delivery |

|

58. Number and distribution of health facilities per 10 000 population | ||

| 59. Number and distribution of inpatient beds per 10 000 population | ||||

| 60. Number of outpatient department visits per 10 000 population per year | ||||

| 61. General service readiness score for health facilities | ||||

| 62. Proportion of health facilities offering specific services | ||||

| 63. Number and distribution of health facilities offering specific services per 10,000 population | ||||

| 64. Specific-services readiness score for health facilities | ||||

| 65. Total ODA Given or Received as a Percent of GNI | ||||

| 66. Percent of Population with Access to Primary Health Care Facilities | ||||

| 67. Immunization Against Infectious Childhood Diseases | ||||

| 68. Contraceptive Prevalence Rate | ||||

| 69. Density of hospitals (per 100 000 population) | ||||

| 70. Generalist | ||||

| 71. Specialist | ||||

| 72. Density of nursing and midwifery personnel (per 10 000 population) | ||||

| 73. Dentistry personnel | ||||

| 74. Pharmaceutical personnel | ||||

| 75. Environmental/public health workers | ||||

| Dimension 6- Coverage | -Financial coverage -Service coverage -Population Coverage |

76. Types of insurance coverage | ||

| 77. Type of membership | ||||

| 78. Coverage essential need | ||||

| 79. Population coverage by different organizations | ||||

| Dimension 7- Stewardship/governance |

|

80. Multi-sectoral strategies such as health, education and labor sectors | ||

| 81. Integrated universal health coverage into its general development plans | ||||

| 82. Having a functional national universal health coverage organization that promotes interaction among government, the private sector and civil society | ||||

| 83. Evaluation of the impact of universal health coverage on its socio-economic status of planning purposes | ||||

| 84. Having a general policy or strategy to promote information and education on universal health coverage | ||||

| 85. Having a policy or strategy to expand access, including among vulnerable groups, to essential services | ||||

| Dimension 8- Global Movements |

|

86. Budget support as a share of GGE | ||

| 87. Sector budget support for health as a share of GGHE | ||||

| 88. Total amount of loans for the health sector |

Figure 2.

The process of identifying, screening and selection of indicators in three phases of the study.

Dimension 1 and 2 – Social Infrastructure and Social Sustainability

The country’s Social Infrastructure and Sustainability dimensions provide general information about the country. These two dimensions include the following indicators: total population, population growth rate, age groups’ breakdown, as well as population’s literacy, education, and poverty levels.

Dimension 3 – Financial and Economic Infrastructure

This dimension assesses country’s financial and economic infrastructures and has three subcategories: country’s GDP per capita growth rate, trends, and adjusted GDP examined in the past years; currency exchange rates (comparison of the monetary unit of the country with the international monetary units to assess the purchasing power); and trends for health expenditure and other health costs (such as General Government Health Expenditure as a percentage of General Government Expenditure (GGE), General Government Health Expenditure as a percentage of Total Health Expenditure (THE) and General Government Health Expenditure per capita (current US$)). These dimensions also include indicators on financial protection within UHC and assess the fair financing, out-of-pocket expenditure, and related impoverishing and catastrophic effects.

Dimension 4 – Population Health Status

This dimension includes indicators of mortality and morbidity, as well as trends of the population health status in recent years, as well as projections of future trends.

Dimension 5 – Service Delivery

There are four subcategories in this dimension: the basic benefits package content, geographic access to health care services, quality of care, and human resources available in the country’s healthcare sector.

Dimension 6 – Coverage

This dimension relates to financial, service, and population coverage. Indicators for this dimension include existing and available types of health insurance, population-level membership coverage, and utilization for each type of health insurance.

Dimension 7 – Governance and Leadership

This dimension has two subcategories: political will and commitment of the country, as well as political leadership and the government’s responsibility. The dimension assesses the country’s commitment and responsibility to UHC by its six descriptive and multiple-choice questions on strategies and programs of the UHC development, evaluation of the impact of UHC national planning purposes, integration of the public and private organizations, and educational and information policies.

Dimension 8 – Global Movements

This dimension has two subcategories: existing international goals and international commitments towards achieving UHC.

According to the experts’ opinion, in order to improve the health system and implement related reform, each country should provide the necessary infrastructure needed under its goals. “The existence and preparation of social infrastructure and attention to social sustainability is important and vital for any country” (p.2, p.9). “The basis for starting any program in the country require to pay attention to the available resources and financial infrastructure” (p.5). “Nothing can be done without preparing necessary infrastructure such as financial infrastructure” (p.1).

Experts also said that transparency in population health status and service delivery are two key dimensions in achieving UHC.

"The population structure in any country should be transparent because it is in this state that a long-term health care program can be developed for that country" (p.8)

“The provision of health services must have a clear framework and be compatible with national and regional health needs” (p.11). According to the experts, all aspects of coverage and financial protection (eg, insurance coverage, membership, health insurance utilization for each type) should be considered and monitored.

According to the identified factors, experts say no action will be successful unless a strong leadership and governance system guides and responds to the program. “All countries that want to be successful on the path of achieving UHC need to followed strong governance and leadership” (p. 3). “The country’s health sector cannot do anything at the national level without leadership and governance” (P.7). Experts believed that in addition to having a national health goal, countries should follow the international policies and international commitments of international organizations such as the World Health Organization.

Discussion

Each country has its own path to achieve UHC, which depends on existing structures, resources, political will, and many other factors.41 Tool designed in this study can be potentially used to track progress towards UHC and related barriers and enablers irrespective of these differences.

The WHO and the World Bank had already previously suggested tracer indicators that allow tracking progress towards UHC in any country. However, these indicators focus on achieving certain metrics of outputs and outcomes of the health system.5,42,43 We complement this great work by developing a comprehensive tool that could allow us to identify potential process barriers and enablers towards UHC and analyze them over time. In comparison to other studies, the suggested tool is focused on the national health system as a whole and can incorporate readily available country-specific data. Our tool incorporates tracer indicators suggested by the WHO, the World Bank, scientists and researchers, but contains eight dimensions: (1–2) social infrastructure and social sustainability; (3) financial and economic infrastructures; (4) population health status; (5) service delivery; (6) coverage; (7) stewardship/governance; and (8) global movements.

Social infrastructure and social sustainability (dimensions 1–2) seem to be influential factors in progress towards UHC: society literacy, community income, poverty, age group, and population.54 To reach social sustainability and providing social infrastructure, as well as providing sustainable development, political will and determination, technical skills, expertise, and administrative cooperation are required. Political commitment can be a pivotal issue in progress to achieve UHC.55

Economic conditions in a particular country (dimension 3) were identified as an important dimension of the tool, and it is one of the main determinants of progress towards UHC. According to the studies conducted in Latin American countries, economic crises, high inflation, and socio-economic inequalities can lead to a failure in progress towards UHC.55,56 To achieve UHC, some countries have adopted important policies and measures that led to the integration of education and health policies in order to eliminate the barriers to achieving UHC.55,56 Social, economic, and political sustainability were already regarded as essential bases for health systems to achieve UHC.57 The same studies have identified the economic crisis and inflation as the main causes of socio-economic problems.55,56 Countries can ease the work of achieving UHC by mitigating the consequences of the economic crisis,58 concentrating on achieving economic growth,56,59,60 and by increasing the GDP share of THE.61,62

A fundamental dimension that challenges any country in achieving UHC is financing.60,63 Financing includes three functions, such as revenue collection, pooling, and strategic purchasing.1 Brazil,64 South Korea,65 and Thailand4 have used strategic purchasing as a key policy instrument to achieve UHC goals of improved and equitable access and financial risk protection.40,41 Insurance agencies can alleviate unnecessary expenditures and out-of-pocket payments if they manage the strategic purchasing function well.66–69 A fragmented pooling system may lead to disorders and is an obstacle in achieving UHC.61 Previous studies have stated that the use of financial mechanisms such as pooling can reduce many of the financial problems of the health systems and thus are effective for progress towards UHC.4,10,70,71

According to Savadoff (2012), all countries that have achieved UHC have done so with significant involvement of the government in health care financing, regulation, and sometimes direct provision of health care services.4 The most tangible and clear aspect of assessing the country’s progress towards UHC is the population’s current health status (dimension 4). Understanding the population’s health status of the country, epidemiologic and demographic transitions, correct assessment of the population’s health needs can help with resources prioritization and allocation according to the needs, as well as provision of necessary quality health services.72–76

Service delivery (dimension 5) is another dimension of the suggested tool with four axes: basic benefits package, geographical access, quality of care, and human resources for health. In regards to the benefits package axes, developing an affordable, sustainable, and equitable basic package of health care services that can serve various population needs is a challenge.77 Studies have shown that people are more interested in the basic benefit package that covers inpatient and outpatient services with high costs.77–79 By covering the basic healthcare needs and resulting in increased people’s satisfaction from the healthcare system, it could be possible to narrow the health gap in the country.80 Access to health care services is another axes of service delivery dimension to progress towards UHC that has been long neglected by many countries,15,76,81,82 with only a few implementing appropriate interventions aimed to improve services provisions. This gap in access to health care services can be narrowed by removing the geographical barriers,83 assuring proper geographical distribution of the services,41 and by providing the necessary drugs.84 The efficiency of the health system is considered an important fundamental function in providing health services and transitioning to UHC. In countries like Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa and Laos (that together account for approximately 40% of the world’s population), political and economic constraints, lack of trained and experienced human resources, large and powerful informal sectors, inefficient political leadership and government in planning, implementation, and management, and lack of sufficient resources related to the efficiency of the health system, are among the key underlying challenges in the transition towards UHC.41,85,86

The sixth dimension of the designed tool focuses on population coverage, financial coverage, and service coverage. According to this dimension, adequate financial risk protection of the citizens that become ill is a major step in achieving UHC.87–89 For this purpose, the fair financial contribution90 and contributions in the form of prepayment mechanisms91,92 can be helpful. The insurance coverage of the country’s population is highly important in achieving UHC. Some studies have previously identified adequate insurance coverage as a primary condition necessary to achieve UHC.93–96 The insurance coverage has direct and indirect effects on other dimensions of UHC (eg, quality of health care provision, catastrophic risk protection). Adequate health insurance system can prevent the catastrophic and impoverishing effects of the out-of-pocket payments and thus protect people from the financial burden of disease.95,97 Different countries use different types of health insurance such as national health insurance,98,99 and social health insurance100,101 that covers and protects the population against financial risks.91,102,103 In Southeast Asian countries, reductions of out-of-pocket payments, increasing accumulation of funding for health, tax-based health care sector financing, ensuring equitable distribution of human resources, and focusing on the reduction of unnecessary health expenditure were identified as key mechanisms and tools in achieving UHC.104 The increasing the share of health spending that is pooled rather than paid out-of-pocket by households, prepayment options, and prepaid health care services have been shown to greatly influential on progress towards UHC.4,71,95,96,105–107 In wealthy nations, such as Germany and the United Kingdom, almost 90% of health care sector financing is done through finance pooling. In middle-income countries such as South Korea and Malaysia that have achieved UHC and in countries like Brazil and Mexico that are about to achieve UHC, more than 65% of health funding is also raised through finance pooling.4 Studies conducted in different countries have demonstrated that out-of-pocket payments and inaccessible or inadequate health services are the main barriers to achieving UHC.88,95,96,106,108–113 Our findings from the systematic literature review indicate that the social and economic sustainability are also main determinants of the progress towards UHC and affect the path and time of achieving UHC.13,57,114

The seventh dimension (Stewardship & Governance) concerns the country’s power of execution and political commitment both inside and outside the country. For this reason, the role of politics in the effective movement towards UHC is a pivotal issue. Political support and legitimacy to create public plans and policies that expand access to health care services, improve equity, and pool financial risks are key factors in progress towards UHC.4 A strong health care services delivery system based on a comprehensive primary health care system facilitates easy access to quality health care services for all citizens. The economic power of a country plays a major role in its political commitment to realizing UHC.57,115 In 2014, major actors in Iran’s health care system sought to achieve UHC by investing political capital and economic resources in implementing the Health Transformation Plan as a highly effective and sustainable policy decision. Political sustainability was identified as an essential element of achieving UHC.57 Achieving UHC requires powerful and multilateral support at the very top of the country’s political system. The political and national commitment to support the healthcare system is a major influencing factor in implementing programs of UHC.62,100,116,117

Global movements (dimension 8) can be reflected by using two major axes: the country’s international goals and international commitments in moving towards UHC by earmarking financial resources. Learning from the experience of countries that managed to achieve UHC successfully, other countries can deal with similar challenges. However, in order to achieve UHC, all strategies, policies, and programs need to be tailored according to the country’s circumstances and needs. Identifying the key determinants of UHC and carefully planning in accordance with them will strengthen the country’s implementation activities while helping to avoid resource waste. Our findings showed that in order to achieve UHC as a major development in public health, all influential factors should be taken into consideration, including economic growth, percentage of national income devoted to health, demographic characteristics, technologies, politics, health financing system, and health spending. Although the factors mentioned above can foster the progress to UHC, the absence of these factors can also negatively impact progress towards UHC.

Strengths and Limitations

We believe that this proposed standalone tool can be further refined and adjusted following a bigger international study using the experience and expertise of other countries. One of the limitations of our tool is that it cannot be used as a standalone measure statically to measure progress towards UHC. We recommend using the developed tool dynamically to show the trends and progress towards UHC, as well as whether barriers and enablers were addressed or enhanced. A need to tailor the content of the tool and its possible necessary adaptation and revision can also affect comparability across countries. Nonetheless, we believe that this limitation is also the tool’s advantage, as it provides usability, flexibility to be adapted by any country to account for its context, needs, and existing structures.

Conclusion

To progress towards UHC, countries can choose and prioritize different policies at various levels of their healthcare system depending on the local context and healthcare system organizational structures. There is no perfect and certain way to achieve UHC. Given the highly diverse health systems, socio-economic constraints, and political forces, each country seeking to achieve UHC may benefit from tailored strategies, policies, and plans. Comprehensive, retrospective, and prospective analyses of the health system, as well as the functional capacity of government, are effective strategies and tools in a successful transition towards UHC.

Countries need a valid tool and frameworks to assess their progress towards UHC. This study offers a tool that can aid in gaining additional insights into the process of such progress by identifying possible barriers and enablers. The proposed tool assesses the main aspects of the healthcare system of the country. Various countries, according to their context, might need to revise the tool’s content and tailor it before application. Nonetheless, countries can use this tool to assess each dimension of their health system in detail and then plan the necessary improvement steps.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Dr. Saber Azami Aghdash and other experts for contribution and time and invaluable comments.

Funding Statement

This study was part of a MSc thesis supported by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Thesis NO: 62231/D/H, ethical code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1395.774). The funding body played no role in the design of the study, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The world health report 2000: health systems: improving performance. WHO; 2000.

- 2.Sekhri N, Savedoff W. Regulating private health insurance to serve the public interest: policy issues for developing countries. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2006;21(4):357–392. doi: 10.1002/hpm.857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans DB, Saksena P, Elovainio R, Boerma T. Measuring Progress Towards Universal Coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savedoff WD, de Ferranti D, Smith AL, Fan V. Political and economic aspects of the transition to universal health coverage. Lancet. 2012;380(9845):924–932. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61083-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Tracking universal health coverage: first global monitoring report. WHO; 2015.

- 6.Supachutikul A. Situation analysis on health insurance and future development. Thailand Health Research Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pannarunothai S, Patmasiriwat D, Srithamrongsawat S. Universal health coverage in Thailand: ideas for reform and policy struggling. Health Policy. 2004;68(1):17–30. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(03)00024-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Basic documents. WHO; 2010.

- 9.Carrin G, Mathauer I, Xu K, Evans DB. Universal coverage of health services: tailoring its implementation. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(11):857–863. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.049387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McIntyre D, Garshong B, Mtei G, et al. Beyond fragmentation and towards universal coverage: insights from Ghana, South Africa and the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(11):871–876. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.053413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans DB, Etienne C. Health systems financing and the path to universal coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(6):402–403. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.078741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mills A, Ataguba JE, Akazili J, et al. Equity in financing and use of health care in Ghana, South Africa, and Tanzania: implications for paths to universal coverage. Lancet. 2012;380(9837):126–133. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60357-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atun R, Aydın S, Chakraborty S, et al. Universal health coverage in Turkey: enhancement of equity. Lancet. 2013;382(9886):65–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61051-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alkenbrack S, Jacobs B, Lindelow M. Achieving universal health coverage through voluntary insurance: what can we learn from the experience of Lao PDR? BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Connell T, Rasanathan K, Chopra M. What does universal health coverage mean? Lancet. 2014;383(9913):277–279. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60955-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Çiçeklioğlu M, Öcek ZA, Turk M, Taner Ş. The influence of a market-oriented primary care reform on family physicians’ working conditions: a qualitative study in Turkey. Eur J Gen Pract. 2015;21(2):1–6. doi: 10.3109/13814788.2014.966075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aran M, Ozceli EA. Universal health coverage for inclusive and sustainable development: country summary report for Turkey. 2014.

- 18.Yardim MS, Cilingiroglu N, Yardim N. Catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment in Turkey. Health Policy. 2010;94(1):26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doshmangir L, As M. Assessment of Turkey’s achievements in universal health coverage. Hakim. 2015;19(3):233–245. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans T, Chowdhury M, Evans D, et al. Thailand’s universal coverage scheme: achievements and challenges: an independent assessment of the first 10 years (2001–2010). Health Insurance System Research Office: Nonthaburi; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsiao W, Shaw R, Fraker A, et al. Social health insurance for developing nations. WBI Development Studies. Washington DC: The World Bank; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed S, Annear PL, Phonvisay B, et al. Institutional design and organizational practice for universal coverage in lesser-developed countries: challenges facing the Lao PDR. Soc Sci Med. 2013;96:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrin G, James C, Organization WH. Reaching universal coverage via social health insurance: key design features in the transition period. 2004.

- 24.Schäfer W, Kroneman M, Boerma W, et al. The Netherlands: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2010;12(1):xxvii, 1–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meng-Kin L. Health care systems m transition II. Singapore, part I. An overview of health care systems in Singapore. J Public Health Med. 1998;20:16–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukawa T Public health insurance in Japan. World Bank; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnsen JR, Bankauskaite V. Norway: European observatory on health systems and policies. Health Syst Transit. 2006;8(1). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vuorenkosky L, Mladovsky P, Finland ME. Health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2008;10(4):1–168. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Busse R, Riesberg A. Health care systems in transition: Germany: world health organization. Regional Office for Europe; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofmarcher MM, Quentin W. Austria: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2012;15(7):1–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. Republic of Korea health system review: Manila: WHO regional office for the western Pacific. 2015.

- 32.World Health Organization. Health care systems in transition: Switzerland. Technical Report. European Observatory on Health Care Systems; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Onarheim KH, Taddesse M, Norheim OF, Abdullah M, Miljeteig I. Towards universal health coverage for reproductive health services in Ethiopia: two policy recommendations. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):86. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0218-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qingyue M, Shenglan T. Universal health care coverage in China: challenges and opportunities. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2013;77:330–340. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.03.091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rao M, Rao KD, Kumar AKS, Chatterjee M, Sundararaman T. Human resources for health in India. Lancet. 2011;377(9765):587–598. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61888-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reich MR, Harris J, Ikegami N, et al. Moving towards universal health coverage: lessons from 11 country studies. Lancet. 2016;387(10020):811–816. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60002-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saksena P, Hsu J, Evans DB. Financial risk protection and universal health coverage: evidence and measurement challenges. PLoS Med. 2014;11(9):e1001701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonilla-Chacín ME, Aguilera N. The Mexican social protection system in health. 2013.

- 39.González-Pier E, Gutiérrez-Delgado C, Stevens G, et al. Priority setting for health interventions in Mexico’s system of social protection in health. Lancet. 2006;368(9547):1608–1618. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69567-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwon S. Payment system reform for health care providers in Korea. Health Policy Plan. 2003;18(1):84–92. doi: 10.1093/heapol/18.1.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marten R, McIntyre D, Travassos C, et al. An assessment of progress towards universal health coverage in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS). Lancet. 2014;384(9960):2164–2171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60075-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Health Organization. Monitoring progress towards universal health coverage at country and global levels: framework, measures and targets. WHO; 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Wagstaff A, Cotlear D, Eozenou PH-V, Buisman LR. Measuring progress towards universal health coverage: with an application to 24 developing countries. Oxford Rev Econ Policy. 2016;32(1):147–189. doi: 10.1093/oxrep/grv019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hogan DR, Stevens GA, Hosseinpoor AR, Boerma T. Monitoring universal health coverage within the sustainable development goals: development and baseline data for an index of essential health services. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(2):e152–e68. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30472-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.World Health Organization. World bank (2017) tracking universal health coverage: 2017 global monitoring report. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lozano R, Fullman N, Abate D, et al. Measuring progress from 1990 to 2017 and projecting attainment to 2030 of the health-related sustainable development goals for 195 countries and territories: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):2091–2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schoen C, Davis K, Collins SR. Building blocks for reform: achieving universal coverage with private and public group health insurance. Health Aff. 2008;27(3):646–657. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boerma T, Eozenou P, Evans D, Evans T, Kieny M-P M-P, Wagstaff A. Monitoring progress towards universal health coverage at country and global levels. PLoS Med. 2014;11(9):e1001731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ng M, Fullman N, Dieleman JL, Flaxman AD, Murray CJ, Lim SS. Effective coverage: a metric for monitoring universal health coverage. PLoS Med. 2014;11(9):e1001730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abdi Z, Majdzadeh R, Ahmadnezhad E. Developing a framework for the monitoring and evaluation of the health transformation plan in the Islamic republic of Iran: lessons learned. East Mediterr Health J. 2019;25:394–405. doi: 10.26719/emhj.18.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neuendorf KA. The Content Analysis Guidebook. Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. SAGE Publications, inc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Solar O, Valentine N, Rice M, Albrecht D, editors. Intersectorality in Health. 7th Global Conference on Health Promotion Promoting Health and Development: Closing the Implementation Gap. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Andrade LOM, Pellegrini Filho A, Solar O, et al. Social determinants of health, universal health coverage, and sustainable development: case studies from Latin American countries. Lancet. 2015;385(9975):1343–1351. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61494-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Atun R, De Andrade LOM, Almeida G, et al. Health-system reform and universal health coverage in Latin America. Lancet. 2015;385(9974):1230–1247. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61646-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Borgonovi E, Compagni A. Sustaining universal health coverage: the interaction of social, political, and economic sustainability. Value Health. 2013;16(1):S34–S8. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quick J, Jay J, Langer A. Improving women’s health through universal health coverage. PLoS Med. 2014;11(1):e1001580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Damrongplasit K, Melnick G. Funding, coverage, and access under Thailand’s universal health insurance program: an update after ten years. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2015;13(2):157–166. doi: 10.1007/s40258-014-0148-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tripathy RM. Public health challenges for universal health coverage. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Saleh SS, Alameddine MS, Natafgi NM, et al. The path towards universal health coverage in the Arab uprising countries Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen. Lancet. 2014;383(9914):368–381. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62339-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van Minh H, Pocock NS, Chaiyakunapruk N, et al. Progress toward universal health coverage in ASEAN. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1):25856. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.25856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McKee M, Balabanova D, Basu S, Ricciardi W, Stuckler D. Universal health coverage: a quest for all countries but under threat in some. Value Health. 2013;16(1):S39–S45. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu Y, Huang C, Colón-Ramos U. Moving toward universal health coverage (UHC) to achieve inclusive and sustainable health development: three essential strategies drawn from asian experience: comment on” Improving the world’s health through the post-2015 development agenda: perspectives from Rwanda”. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(12):869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.ChangBae C, SoonYang K, JunYoung L, SangYi L. Republic of Korea. Health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2009;11(7). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hajizadeh M, Nghiem HS. Out-of-pocket expenditures for hospital care in Iran: who is at risk of incurring catastrophic payments? Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2011;11(4):267–285. doi: 10.1007/s10754-011-9099-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kavosi Z, Rashidian A, Pourreza A, et al. Inequality in household catastrophic health care expenditure in a low-income society of Iran. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(7):613–623. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moghadam MN, Banshi M, Javar MA, Amiresmaili M, Ganjavi S. Iranian household financial protection against catastrophic health care expenditures. Iran J Public Health. 2012;41(9):62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tangcharoensathien V, Limwattananon S, Patcharanarumol W, Thammatacharee J, Jongudomsuk P, Sirilak S. Achieving universal health coverage goals in Thailand: the vital role of strategic purchasing. Health Policy Plan. 2014;30(9):1152–1161. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.World Health Organization. World Health Report, 2010: health systems financing the path to universal coverage. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Xu K, Evans DB, Carrin G, Aguilar-Rivera AM, Musgrove P, Evans T. Protecting households from catastrophic health spending. Health Aff. 2007;26(4):972–983. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Adebayo EF, Uthman OA, Wiysonge CS, Stern EA, Lamont KT, Ataguba JE. A systematic review of factors that affect uptake of community-based health insurance in low-income and middle-income countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):543. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1179-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alkenbrack S, Jacobs B, Lindelow M. Achieving universal health coverage through voluntary insurance: what can we learn from the experience of Lao PDR? BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Amaya JL, Ruiz F, Trujillo AJ, Buttorff C. Identifying barriers to move to better health coverage: preferences for health insurance benefits among the rural poor population in La Guajira, Colombia. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2016;31(1):126–138. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Blanchet K, Gordon I, Gilbert CE, Wormald R, Awan H. How to achieve universal coverage of cataract surgical services in developing countries: lessons from systematic reviews of other services. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2012;19(6):329–339. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2012.717674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aguilera X, Castillo-Laborde C, Najera-de Ferrari M, Delgado I, Ibañez C. Monitoring and evaluating progress towards universal health coverage in Chile. PLoS Med. 2014;11(9):e1001676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Onwujekwe O, Onoka C, Uguru N, et al. Preferences for benefit packages for community-based health insurance: an exploratory study in Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):162. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dong H, Kouyate B, Cairns J, Sauerborn R. Differential willingness of household heads to pay community-based health insurance premia for themselves and other household members. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19(2):120–126. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dror DM, Koren R, Ost A, Binnendijk E, Vellakkal S, Danis M. Health insurance benefit packages prioritized by low-income clients in India: three criteria to estimate effectiveness of choice. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(4):884–896. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fairbank A. Sources of financial instability of community-based health insurance schemes: how could social reinsurance help? Partners for Health Reformplus, Abt Associates. 2003.

- 81.Van Lerberghe W. The world health report 2008: primary health care: now more than ever: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Scheil‐Adlung X. Revisiting policies to achieve progress towards universal health coverage in low‐income countries: realizing the pay‐offs of national social protection floors. Int Soc Secur Rev. 2013;66(3–4):145–170. doi: 10.1111/issr.12022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alebachew A, Hatt L, Kukla M. Monitoring and evaluating progress towards universal health coverage in Ethiopia. PLoS Med. 2014;11(9):e1001696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wirtz VJ, Hogerzeil HV, Gray AL, et al. Essential medicines for universal health coverage. Lancet. 2017;389(10067):403–476. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31599-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rao KD, Petrosyan V, Araujo EC, McIntyre D. Progress towards universal health coverage in BRICS: translating economic growth into better health. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(6):429–435. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.127951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Koohpayehzadeh J, Azami-Aghdash S, Derakhshani N, et al. Best practices in achieving universal health coverage: a scoping review. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 87.Knaul FM, González-Pier E, Gómez-Dantés O, et al. The quest for universal health coverage: achieving social protection for all in Mexico. Lancet. 2012;380(9849):1259–1279. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61068-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Higashi H, Khuong TA, Ngo AD, Hill PS. Population-level approaches to universal health coverage in resource-poor settings: lessons from tobacco control policy in Vietnam. MEDICC Rev. 2011;13(3):39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mills A, Ally M, Goudge J, Gyapong J, Mtei G. Progress towards universal coverage: the health systems of Ghana, South Africa and Tanzania. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(suppl_1):i4–i12. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Okoroh JS, Chia V, Oliver EA, Dharmawardene M, Riviello R. Strengthening health systems of developing countries: inclusion of surgery in universal health coverage. World J Surg. 2015;39(8):1867–1874. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3031-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.McIntyre D, Ranson MK, Aulakh BK, Honda A. Promoting universal financial protection: evidence from seven low-and middle-income countries on factors facilitating or hindering progress. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11(1):36. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-11-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Patel V, Parikh R, Nandraj S, et al. Assuring health coverage for all in India. Lancet. 2015;386(10011):2422–2435. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00955-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Davis K. Universal coverage in the United States: lessons from experience of the 20th century. J Urban Health. 2001;78(1):46–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ha BT, Frizen S, Thi LM, Duong DT, Duc DM. Policy processes underpinning universal health insurance in Vietnam. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1):24928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ibrahimipour H, Maleki M-R, Brown R, Gohari M, Karimi I, Dehnavieh R. A qualitative study of the difficulties in reaching sustainable universal health insurance coverage in Iran. Health Policy Plan. 2011;26(6):485–495. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kumar AS, Chen LC, Choudhury M, et al. Financing health care for all: challenges and opportunities. Lancet. 2011;377(9766):668–679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61884-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Donabedian A. An Introduction to Quality Assurance in Health Care. Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hatanaka T, Eguchi N, Deguchi M, Yazawa M, Ishii M. Study of global health strategy based on international trends:—promoting universal health coverage globally and ensuring the sustainability of Japan’s universal coverage of health insurance system: problems and proposals. Japan Med Assoc J. 2015;58(3):78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kwon S. Thirty years of national health insurance in South Korea: lessons for achieving universal health care coverage. Health Policy Plan. 2008;24(1):63–71. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tejativaddhana P, Briggs D, Fraser J, Minichiello V, Cruickshank M. Identifying challenges and barriers in the delivery of primary healthcare at the district level: a study in one Thai province. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2013;28(1):16–34. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Doshmangir L, Rashidian A, Kouhi F, Gordeev VS. Setting health care services tariffs in Iran: half a century quest for a window of opportunity. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 102.Bredenkamp C, Evans T, Lagrada L, Langenbrunner J, Nachuk S, Palu T. Emerging challenges in implementing universal health coverage in Asia. Soc Sci Med. 2015;145:243–248. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nyandekwe M, Nzayirambaho M, Kakoma JB. Universal health coverage in Rwanda: dream or reality. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;17. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.17.232.3471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bennett S, Ozawa S, Rao KD. Which path to universal health coverage? Perspectives on the World Health Report 2010. PLoS Med. 2010;7(11):e1001001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.World Health Organization. The World Health Report: Health Systems Financing: The Path to Universal Coverage. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ha BT, Frizen S, Thi LM, Duong DT, Duc DM. Policy processes underpinning universal health insurance in Vietnam. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:24928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Davis MK. Universal coverage in the United States: lessons from experience of the 20th century. J Urban Health. 2001;78(1):46–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mathauer I, Doetinchem O, Kirigia J, Carrin G. Reaching universal coverage by means of social health insurance in Lesotho? Results and implications from a financial feasibility assessment. Int Soc Secur Rev. 2011;64(2):45–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-246X.2011.01392.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fattore G, Tediosi F. The importance of values in shaping how health systems governance and management can support universal health coverage. Value Health. 2013;16(1):S19–S23. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ferré F, de Belvis AG, Valerio L, et al. Italy: health system review. 2014. [PubMed]

- 111.Garcia-Subirats I, Vargas I, Mogollón-Pérez AS, et al. Barriers in access to healthcare in countries with different health systems. A cross-sectional study in municipalities of central Colombia and north-eastern Brazil. Soc Sci Med. 2014;106:204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Govender V, Chersich MF, Harris B, et al. Moving towards universal coverage in South Africa? Lessons from a voluntary government insurance scheme. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:19253. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.19253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wahlster P, Scahill S, Lu CY. Barriers to access and use of high cost medicines: a review. Health Policy Technol. 2015;4(3):191–214. doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2015.04.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yasar GY, Ugurluoglu UE. Can Turkey’s general health insurance system achieve universal coverage? Int J Health Plann Manage. 2011;26(3):282–295. doi: 10.1002/hpm.1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Maeda A, Araujo E, Cashin C, Harris J, Ikegami N, Reich MR. Universal health coverage for inclusive and sustainable development: a synthesis of 11 country case studies. World Bank Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Shibuya K, Hashimoto H, Ikegami N, et al. Future of Japan’s system of good health at low cost with equity: beyond universal coverage. Lancet. 2011;378(9798):1265–1273. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61098-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Abiiro GA, De Allegri M. Universal health coverage from multiple perspectives: a synthesis of conceptual literature and global debates. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2015;15(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s12914-015-0056-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]