Abstract

Background

Cerium oxide nanoparticles (CeO2NPs) are potent scavengers of cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). Their antioxidant properties make CeO2NPs promising therapeutic agents for bone diseases and bone tissue engineering. However, the effects of CeO2NPs on intracellular ROS production in osteoclasts (OCs) are still unclear. Numerous studies have reported that intracellular ROS are essential for osteoclastogenesis. The aim of this study was to explore the effects of CeO2NPs on osteoclast differentiation and the potential underlying mechanisms.

Methods

The bidirectional modulation of osteoclast differentiation by CeO2NPs was explored by different methods, such as fluorescence microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), and Western blotting. The cytotoxic and proapoptotic effects of CeO2NPs were detected by cell counting kit (CCK-8) assay, TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay, and flow cytometry.

Results

The results of this study demonstrated that although CeO2NPs were capable of scavenging ROS in acellular environments, they facilitated the production of ROS in the acidic cellular environment during receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand (RANKL)-dependent osteoclast differentiation of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs). CeO2NPs at lower concentrations (4.0 µg/mL to 8.0 µg/mL) promoted osteoclast formation, as shown by increased expression of Nfatc1 and C-Fos, F-actin ring formation and bone resorption. However, at higher concentrations (greater than 16.0 µg/mL), CeO2NPs inhibited osteoclast differentiation and promoted apoptosis of BMMs by reducing Bcl2 expression and increasing the expression of cleaved caspase-3, which may be due to the overproduction of ROS.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that CeO2NPs facilitate osteoclast formation at lower concentrations while inhibiting osteoclastogenesis in vitro by inducing the apoptosis of BMMs at higher concentrations by modulating cellular ROS levels.

Keywords: cerium oxide nanoparticles, osteoclast, osteoclastogenesis, ROS, apoptosis

Introduction

As one of the lanthanide elements, cerium (Ce) is the most abundant among the rare-earth elements. The metal oxide form of Ce, cerium oxide, enables quick and regenerative redox cycling between two oxidation states, Ce3+ and Ce4+, due to the oxygen vacancies in its crystal lattice, which endows cerium oxide with robust catalytic activity.1 In addition, because of the high surface-volume ratio and monodispersion, an increased number of stable surface oxygen vacancies are found in cerium oxide nanoparticles (CeO2NPs) compared with those of cerium oxide bulk material when they reach the nanoscale (less than 100 nm).2–4 Hence, the exposed surface oxygen vacancies in CeO2NPs act as reaction sites, facilitate redox cycling and enhance catalytic activity. CeO2NPs are multienzymes that possess catalase-mimetic,5,6 superoxide dismutase-mimetic,7,8 peroxidase-mimetic activities9 when applied in cell culture and animal experiments. In most reports, CeO2NPs scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS), including hydrogen peroxide and free radicals, such as·OH, O2-,·NO, within the cellular environment, thus attenuating ROS production and organ dysfunction in ROS-related diseases, including myocardial damage, systemic inflammatory reaction syndrome, psoriasis and Alzheimer’s disease.10–14 However, there are also other reports demonstrating that in some acidic environments, such as cancer cells, CeO2NPs exhibit oxidase-like activity, enhancing intracellular ROS production and cell toxicity.15–17

In recent years, many researchers have explored the application of CeO2NPs in bone regeneration and bone tissue engineering. Many researchers have focused on mesenchymal stem cells and osteogenesis. Previous studies demonstrated that CeO2NPs alone or CeO2NPs composed of implant coating and scaffolds facilitate cell viability and osteoblastic differentiation of bone mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) by scavenging ROS in the cell microenvironment.18–23 In this regard, CeO2NPs seem to have some promising effects on bone volume maintenance and bone defect repair. However, the effects of CeO2NPs on osteoclastogenesis have not yet been clearly explored. Few studies have focused on the effects of CeO2NPs on osteoclast (OC) formation. A previous report indicated that citrate-stabilized CeO2NPs at a concentration of 5 µM facilitated receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand (RANKL)-dependent osteoclastogenesis by upregulating the expression of Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α); however, this study did not detect intracellular ROS levels or relative pathway activation.24 Thus, it is important to clarify the effects of CeO2NPs on osteoclastogenesis for better evaluation of the practicability of CeO2NP-related therapy.

Although excessive production of cellular ROS causes lipid peroxidation, protein denaturation, and nucleic acid damage, leading to cell apoptosis and death, increasing evidence confirms that physiological ROS levels play a crucial role in osteoclastogenesis.25–28 Osteoclasts are mainly derived from bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs). Under the stimulation of two indispensable factors for osteoclastogenesis, macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and RANKL, endogenous ROS production in BMMs is activated, followed by activation of downstream signaling pathways, including the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and NF-κB pathway, and ultimately contributes to BMMs fusion into large multinucleated mature osteoclasts.28–30 Lee, N. K found that ROS levels in BMMs were significantly elevated and peaked at 10 min after RANKL stimulation. After treatment with N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a chemical antioxidant, RANKL-stimulated ROS production in BMMs was significantly inhibited in a dose-dependent manner.25 In addition, accompanied by the fusion of BMMs, the expression of carbonic anhydrase II is also highly elevated, leading to acidification of osteoclasts and a reduced pH cellular environment, which enable the absorptive function of osteoclasts.31 Although previous studies have demonstrated that CeO2NPs scavenge ROS in macrophages in other organs, such as Kupffer cells,10 the ROS scavenging capability of CeO2NPs has not been elucidated in acidic osteoclasts.

Recent studies have demonstrated that the ROS-scavenging ability of CeO2NPs was converted into oxidative activity in acidic environments, such as in comparatively acidic cancer cells.32–34 The redox cycle from Ce3+ to Ce4+ is blocked by excessive H+, resulting in blockade of catalytic activity and accumulation of H2O2 in the cellular microenvironment, ultimately leading to cell damage and dysfunction.35 Wason MS found that pretreatment with 10 μM CeO2NPs enhanced ROS production in response to radiation in acidic acellular medium and acidic pancreatic cancer cells.16 This suggests that CeO2NPs, which are potent ROS scavengers, might demonstrate ROS-promoting effects during osteoclastogenesis.

In this study, we utilized CeO2NPs with an average diameter of 20 nm at different concentrations to investigate their potential regulatory effects on ROS production and signal transduction during osteoclastogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Characterization of CeO2NPs

CeO2NPs were purchased from Engi-Mat (Lexington, Kentucky, USA). The purity of the cerium oxide nanoparticles was greater than 99.9%. The crystallinity was determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku Corporation, RigakuD/Max-2200 PC, Japan). The surface chemical composition and valence state of CeO2NPs were determined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Scientific, ESCALAB 250, USA). The crystal structure and size were observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Thermo Scientific, FEI Talos L120C, USA). The crystal size observed by XRD was calculated according to the Scherrer equation.36

Electron Spin Resonance (ESR)

An ESR paramagnetic spectrometer (JEOL, JEOL-FA200, Japan) was used to detect the ROS scavenging ability of CeO2NPs in the acellular environment according to the manufacturer’s instructions for 5,5′-dimethylpyrroline N-oxide (DMPO, Dojindo, Japan). For hydroxyl radical scavenging measurements, CeO2NPs at a final concentration of 256 mg/L were incubated with 100 mM DMPO, 0.05 U/mL xanthine oxidase (Solarbio Life Science, China) and 0.5 mM hypoxanthine (Solarbio Life Science, China) in water for 1 min, and then hydroxyl radicals were determined by ESR. To induce superoxide radicals for scavenging measurement, CeO2NPs at a final concentration of 256 mg/L were incubated with 100 mM DMPO, 0.05 U/mL xanthine oxidase, 0.5 mM hypoxanthine, in 100% ethanol for 1 min, and then the level of O2- was determined by ESR.

Cell Culture

BMMs were isolated as previously described.37 C57BL/6 mice (4-week-old, male) were purchased from Shanghai SIPPR-Bk Lab Animal Company. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethical Committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital. In brief, all mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, then tibiae and femora were harvested. Bone marrow cells were rinsed, added to culture plate and then cultured in α-MEM medium (HyClone, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA), 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (HyClone, USA) and 30 ng/mL M-CSF (R&D, USA) at 5% CO2 and 37 °C for 6 days. The culture medium containing M-CSF (30 ng/mL) was replaced every 2 days. For CeO2NP treatment, CeO2NPs were dispersed in sterile double distilled water (ddH2O) and treated with ultrasonic treatment for 10 min before being added to the culture medium.

Cellular Internalization of CeO2NPs

Cellular internalization of CeO2NPs was observed by TEM (FEI Talos L120C, Thermo Scientific, USA). Briefly, BMMs were treated with various concentrations of CeO2NPs for the indicated times, fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 4% osmic acid and dehydrated in graded ethanol. Then, the cells were permeated with resin and polymerized with a resin column at 65 °C for 2 days. After this, resin columns were sliced, stained and observed by TEM.

Cell Viability Assay

The cell viability of BMMs that were treated with CeO2NPs was determined using a Cell Counting Kit (CCK-8, Dojindo Laboratories, Japan) assay. Cells were seeded in 96-well culture plates at a density of 1×104 cells per well. After incubating with different concentrations of CeO2NPs for 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 120 h, the medium was replaced with fresh culture medium containing 1/10 (v/v) CCK-8 solution and further incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Then, the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Tecan, M200pro, Switzerland).

Tartrate-Resistant Acid Phosphatase (TRAP) Staining Assay

BMMs were seeded in 96-well culture plates (1×104 cells per well) and incubated with α-MEM medium containing M-CSF (30 ng/mL) for 24 h. The cells were pretreated with different concentrations of CeO2NPs for another 24 h. Subsequently, the culture medium was replaced with fresh culture medium containing M-CSF (30 ng/mL) and RANKL (50 ng/mL), and the cells were incubated for 6 days.37 The culture medium containing M-CSF, RANKL and different concentrations of CeO2NPs was replaced every 2 days. On day 4, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution at 37°C for 20 min and then stained with a TRAP staining kit (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) according to the manufacturer’s procedures. After staining, the number and area of TRAP+ osteoclasts containing 3 or more nuclei were observed by open-field microscopy (Olympus, IX71, Japan) and analyzed by ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA).

Actin Ring Formation Assay

BMMs were seeded in 96-well culture plates (1×104 per well), cultured in complete α-MEM medium and treated with different concentrations of CeO2NPs in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL for 6 days. After this, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 1 h and washed with PBS 3 times. Then, the cells were stained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (Abcam, UK) for 30 min and subsequently stained with 4ʹ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 10 min and washed with PBS 3 times. Finally, the actin rings were observed and imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, IX71, Japan).

Bone Resorption Assay

The bovine bone slices were sterilized by ethylene oxide sterilization and then soaked in culture medium in a 96-well culture plate for 24 h to remove residual ethylene oxide. Then, BMMs (1×104 cells per well) were seeded on the bovine bone slices and were pretreated with different concentrations of CeO2NPs (0, 4, 8, 16, and 32 mg/L). After this, the cells were cultured in the presence of M-CSF (30 ng/mL) and RANKL (50 ng/mL) for 2 weeks. The culture medium containing different concentrations of CeO2NPs, M-CSF and RANKL was replaced every 2 days. After 2 weeks, the cells on the slices were removed using 0.25% EDTA-Trypsin, and the bone slices were dehydrated by gradient dehydration and then coated with gold for observation under a scanning electron microscope (SEM, HITACHI, S4800, Japan).37

Intracellular pH Measurement

The intracellular pH of BMMs and osteoclasts was measured using a pH-sensitive fluorescent probe, 2ʹ,7ʹ-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein, acetoxymethyl ester (BCECF-AM, Beyotime Biotechnology, China) and the nigericin calibration method.38 Briefly, BMMs were seeded in flat clear-bottom black 96-well microplates (Corning, USA) at a density of 2×104 cells per well and pretreated with various concentrations of CeO2NPs for 24 h. Then, the cells were stimulated with M-CSF (30 ng/mL) and RANKL (50 ng/mL) for 2 or 4 days. On day 2 or day 4, the cells were washed with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) 3 times and then incubated in HBSS with 3 μM BCECF-AM at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 30 min. Then, the cells were washed with prewarmed HBSS at pH 7.0 3 times. The fluorescence was determined using a microplate reader (Tecan, M200pro, Switzerland) with an emission wavelength of 535 nm and dual-excitation wavelengths of 490 nm and 430 nm. BMMs were also calibrated in Na+-free calibration solution (135 mM KCl, 2 mM K2HPO2, 20 mM HEPES, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgSO4, and 10 μM nigericin) with different pH values (5.5, 6.0, 6.5, 7.0, 7.5, and 8.0) 5 times, and dual-excitation fluorescence measurements were performed to obtain a standard curve. Intracellular pH (pHi) was calculated according to the standard curve.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

qRT-PCR was performed as previously described.39 BMMs were cultured in 6-well culture plates (3×105 cells per well) and pretreated with various concentrations of CeO2NPs for 24 h. Then, the cells were stimulated with M-CSF (30 ng/mL) and RANKL (50 ng/mL) for 3 days. Total RNA from BMMs was isolated using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, USA), and 1 μg of total RNA template was transcribed into cDNA using All-in-One cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (Bimake, USA). Real-time PCR was performed by using SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Bimake, USA) on a Real-Time PCR platform (Applied Biosystems, ABI 7500, USA). All genes measured were normalized to beta-actin and calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method. The primers we used for analysis are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences for qRT-PCR

| Gene | Forward Primer Sequence (5ʹ-3ʹ) | Reverse Primer Sequence (5ʹ-3ʹ) |

|---|---|---|

| Acp5 | CACTCCCACCCTGAGATTTGT | CATCGTCTGCACGGTTCTG |

| Ctsk | GGACCCATCTCTGTGTCCAT | CCGAGCCAAGAGAGCATATC |

| C-Fos | CCAGTCAAGAGCATCAGCAA | AAGTAGTGCAGCCCGGAGTA |

| Calcr | CGGACTTTGACACAGCAGAA | AGCAGCAATCGACAAGGAGT |

| Traf6 | AAACCACGAAGAGGTCATGG | GCGGGTAGAGACTTCACAGC |

| Dcstamp | AAAACCCTTGGGCTGTTCTT | AATCATGGACGACTCCTTGG |

| Bcl2 | ATGCCTTTGTGGAACTATATGGC | GGTATGCACCCAGAGTGATGC |

| Bax | TGAAGACAGGGGCCTTTTTG | AATTCGCCGGAGACACTCG |

| Bad | AAGTCCGATCCCGGAATCC | GCTCACTCGGCTCAAACTCT |

| Ca2 | TCCCACCACTGGGGATACAG | CTCTTGGACGCAGCTTTATCATA |

| Beta-actin | AGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGACA | CACTGTGTTGGCATAGAGGTC |

Abbreviations: Acp5, acid phosphatase 5; Ctsk, cathepsin K; C-Fos, proto-oncogene C-Fos; Calcr, calcitonin receptor; Traf6, TNF receptor-associated factor 6; Dcstamp, dendrocyte expressed seven transmembrane protein; Bcl2, BCL2 apoptosis regulator; Bax, BCL2-associated X, apoptosis regulator; Bad, BCL2-associated agonist of cell death; Ca2, carbonic anhydrase 2.

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed as previously described.40 BMMs were seeded in 6-well culture plates (8×105 cells per well) overnight. The cells were administered different concentrations of CeO2NPs and subsequently cultured in the presence or absence of RANKL for the indicated times. After this, the cells were washed once with PBS, lysed in cold SDS lysis buffer containing 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, Beyotime Biotechnology, China) and phosphatase inhibitors (Bimake, USA), and centrifuged at 12,000 rcf for 10 min. The total protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China). An equal amount of protein (20 μg) was separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore, USA). The membrane was blocked in 5% skim milk, incubated in primary antibody solution overnight, incubated in appropriate secondary antibody and detected by an infrared imaging system (Odyssey, USA). For P38, ERK, and JNK detection, the same membrane was probed for p-P38, p-ERK, and p-JNK, stripped and reincubated. The primary antibodies used were as follows: Nfatc1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-7294, USA, 1:1000), p-Nfatc1 (Affinity Biosciences, AF8012, USA, 1:1000), GAPDH (Affinity Biosciences, AF7021, USA, 1:1000), Lamin B1 (Cell Signaling Technology, 13,435, USA, 1:1000), p-ERK (Cell Signaling Technology, 4370, USA, 1:1000), ERK (Cell Signaling Technology, 4695, USA, 1:1000), p-JNK (Cell Signaling Technology, 4668, USA, 1:1000), JNK (Cell Signaling Technology, 9252, USA, 1:1000), p-P38 (Cell Signaling Technology, 4092, USA, 1:1000), P38 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9212, USA, 1:1000), p-IKKα/β (Cell Signaling Technology, 2697, USA, 1:1000), IKKα (Cell Signaling Technology, 2682, USA, 1:1000), p-IKBα (Cell Signaling Technology, 2859, USA, 1:1000), IKBα (Cell Signaling Technology, 4812, USA, 1:1000), p-P65 (Cell Signaling Technology, 3033, USA, 1:1000), P65 (Cell Signaling Technology, 8242, USA, 1:1000), Bcl2 (Abcam, ab32124, UK, 1:1000), cleaved-Caspase3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9661, USA, 1:1000), Caspase3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9662, USA, 1:1000), and β-Actin (Cell Signaling Technology, 4970, USA, 1:1000).

Intracellular ROS Assay

Intracellular ROS production was determined as previously described.25 Briefly, BMMs were seeded in 35 mm dishes, pretreated with different concentrations of CeO2NPs for 24 h and then stimulated with RANKL (50 ng/mL) and M-CSF (30 ng/mL) for the indicated times. For ROS detection, the cells were washed with PBS 3 times. Then, the cells were probed with 10 μM DCFH-DA (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) dissolved in HBSS for 30 min and washed 3 times. Then, the cells were observed under a laser confocal scanning microscope (LCSM, Leica, Germany). For early-stage ROS measurement, BMMs were pretreated with various concentrations of CeO2NPs and probed with 10 μM DCFH-DA for 30 min. Then, the cells were transferred from the plate to sterile tubes with 0.25% EDTA-free trypsin, stimulated with HBSS containing 30 ng/mL RANKL for 10 min and immediately subjected to flow cytometry on a flow cytometer (BD Bioscience, LSRFortessa, USA). The fluorescence of DCF was measured with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm with an emission wavelength ranging from 515 nm to 540 nm.

In vitro TUNEL Assay

BMM apoptosis was determined by using a One-Step TUNEL Assay Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, C1086, China) according to the manufacturer’s procedures. Briefly, BMMs were seeded in 35 mm confocal dishes and pretreated with various concentrations of CeO2NPs for 48 h. Then, the cells were washed once with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h. After this, PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 was used to permeabilize the cells. Then, the cells were incubated in TUNEL staining solution for 1 h and subsequently stained with DAPI solution. Finally, the cells were washed with PBS 3 times and observed under a laser confocal scanning microscope (LCSM, Leica, Germany). For TUNEL detection, the excitation wavelength and the emission wavelength were set at 488 nm and 520 nm, respectively. For DAPI detection, the excitation wavelength and the emission wavelength were set at 400 nm and 488 nm, respectively.

Flow Cytometry to Analyze BMM Apoptosis

BMMs were seeded in 6-well culture plates (5×105 cells per well) and treated with various concentrations of CeO2NPs, M-CSF (30 ng/mL) and RANKL (50 ng/mL) for 48 h. Then, BMMs were collected using EDTA-free trypsin and stained with Annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide (PI) double (BD Bioscience, USA) according to the manufacturer’s procedures. After this, the cell suspension was subjected to flow cytometry on a flow cytometer (BD Bioscience, LSR Fortessa, USA).

Statistical Analysis

All data in the experiments were analyzed with SPSS 13.0 software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, USA) and are presented as the means ± standard deviation. We used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Tukey’s test to compare multigroup parametric data. The level of statistical significance was set at P<0.05. # and * indicate P<0.05 when comparing the control group with the vehicle group and the treated groups with the vehicle groups, respectively. ## and ** indicate P<0.01 when comparing the control group with the vehicle group and the treated groups with the vehicle groups, respectively.

Results

Characterization of CeO2NPs

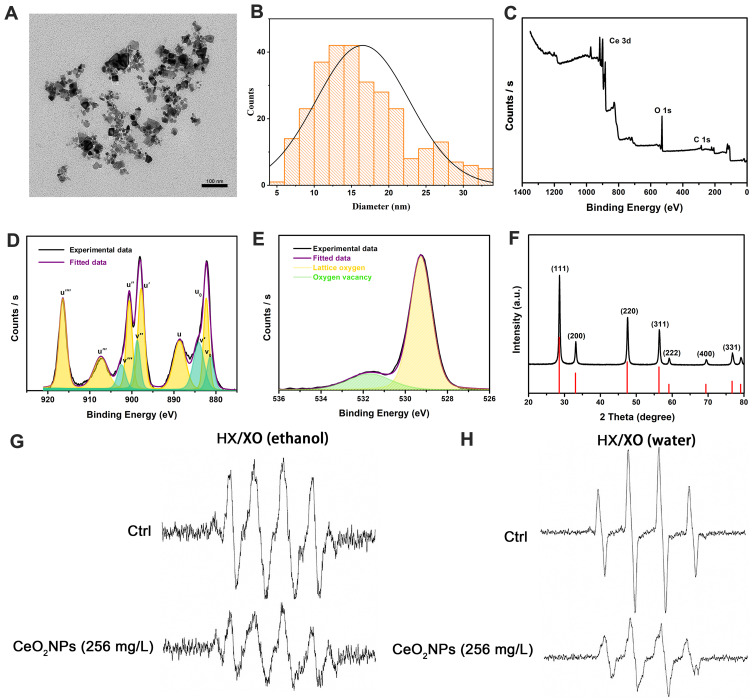

The morphology and size of CeO2NPs were observed by TEM. Figure 1A showed that CeO2NPs presented a cubic structure. Figure 1B demonstrated that the diameter of CeO2NPs ranged from 5 nm to 35 nm, with a mean diameter of 17 nm. XPS results (Figure 1C–E) showed that the relative levels of Ce4+, Ce3+, and oxygen vacancies were 73%, 27%, and 19.67%, respectively. XRD measurements (Figure 1F) further validated the size distribution of CeO2NPs, with a 23.8 nm mean Scherrer diameter. These results suggest that the CeO2NPs used in this experiment had a relatively high Ce4+ content and oxygen vacancies and might be a possible ROS scavenger.

Figure 1.

Characterization of CeO2NPs and the ROS scavenging ability of CeO2NPs in acellular environments.

Notes: (A) Morphology of CeO2NPs was observed by TEM. Scale bar = 100 nm (B) Size distribution of CeO2NPs was measured by TEM. (C) Full XPS spectra of CeO2NPs. (D) Development of Ce 3d XPS spectra and fitted Ce 3d XPS spectra. (E) Analysis results of the relative content of oxygen vacancies. (F) XRD pattern of CeO2NPs. (G) Superoxide radicals that were generated by 0.5 mM hypoxanthine and 0.05 U/mL xanthine oxidase in ethanol solution and superoxide radicals that were scavenged by 256 mg/L CeO2NPs. (H) Hydroxyl radicals that were generated by 0.5 mM hypoxanthine and 0.05 U/mL xanthine oxidase in water solution and hydroxyl radicals that were scavenged by 256 mg/L CeO2NPs.

Abbreviations: HX, hypoxanthine; XO, xanthine oxidase.

ROS Scavenging Ability of CeO2NPs in an Acellular Environment

To validate the ROS scavenging ability of CeO2NPs, we used ESR to test the hydroxyl radical and superoxide radical scavenging ability of CeO2NPs. Xanthine oxidase oxidizes hypoxanthine and generates hydroxyl radicals and superoxide radicals in water and ethanol solutions, respectively. In contrast to the blank control without CeO2NPs, CeO2NPs (256 mg/L) effectively reduced the peak amplitude of ESR signals of the hydroxyl radical (59%) and superoxide radical (35%) (Figure 1G and H). These results suggest that CeO2NPs attenuate ROS production in acellular HX/XO systems.

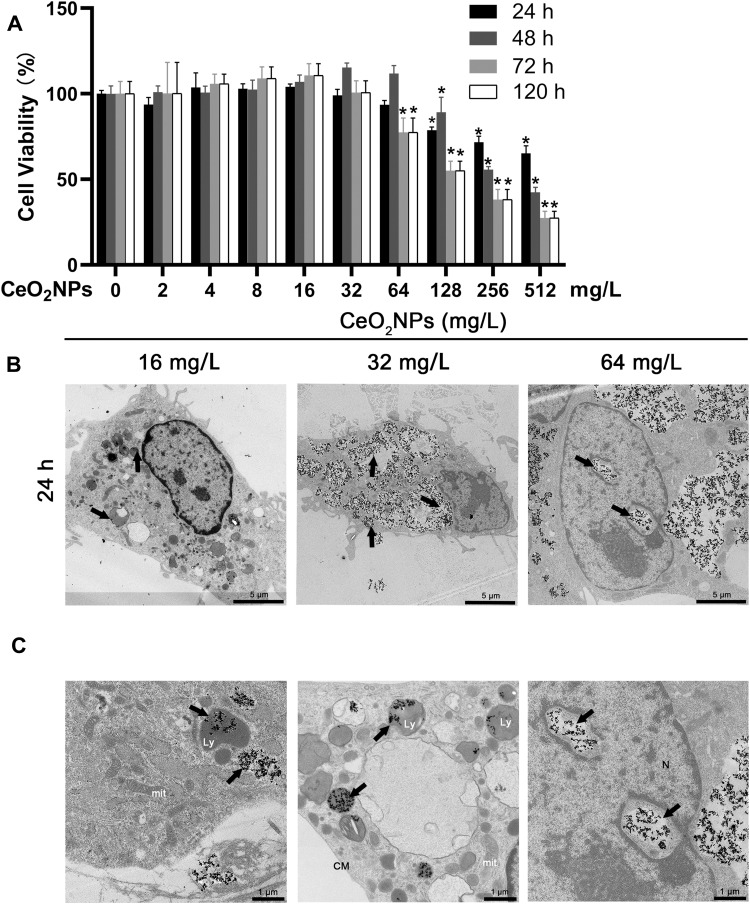

Effects of CeO2NPs on the Viability of BMMs

To determine the cell viability and proliferation of BMMs at various concentrations of CeO2NPs, we used the CCK-8 assay in this experiment (Figure 2A). CeO2NPs showed no evident cytotoxic effects on cell viability or proliferation until reaching a threshold of 128 mg/L after 1 and 2 days. And CeO2NPs showed cytotoxic effects on BMMs when the concentration of CeO2NPs was above 64 mg/L after 3 and 5 days. Due to this result, the concentrations of CeO2NPs used to pretreat the BMMs were no greater than 64 mg/L. These results also indicate that CeO2NPs are a potential biocompatible nanomedicine or delivery tool.

Figure 2.

Effects of CeO2NPs on cell viability of BMMs and CeO2NP internalization by BMMs.

Notes: (A) Cell viability of BMMs that were treated with various concentrations of CeO2NPs for 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, 120 h was measured by CCK-8 assay. (B) Representative low-magnification TEM images of BMMs that were treated with 16, 32, and 64 mg/L CeO2NPs for 24 h. Scale bar = 5 µM. (C) Representative high-magnification TEM images of the intracellular distribution of CeO2NPs in the cytoplasm, lysosome, and nucleus. Scale bar = 1 µM. CeO2NPs are indicated by black arrows. *Indicates p<0.05 compared with the control group (0 mg/L, RANKL-).

Abbreviations: mit, mitochondria; Ly, lysosome; CM, cell membrane; N, nucleus.

Cellular Internalization of CeO2NPs

Cellular internalization of CeO2NPs was observed by TEM. As shown in Figure 2B, after treatment with CeO2NPs for 24 h, CeO2NPs that were internalized by BMMs were found mainly in the cytoplasm and lysosomes (Figure 2C). Most cells in the 8 and 16 mg/L CeO2NPs groups maintained normal cellular morphology. However, in the 64 mg/L CeO2NPs group, some cells were filled with a large number of CeO2NPs, and normal structure of other organelles was absent in these cells (Figure 2B). We also found that CeO2NPs entered the nucleus and disrupted the integrity of the cell membrane and organelles (Figure 2C). These results indicate that CeO2NPs are internalized by BMMs and distributed in the cytoplasm, lysosomes and nucleus. In addition, relatively high concentrations of CeO2NPs resulted in the destruction of cellular structure.

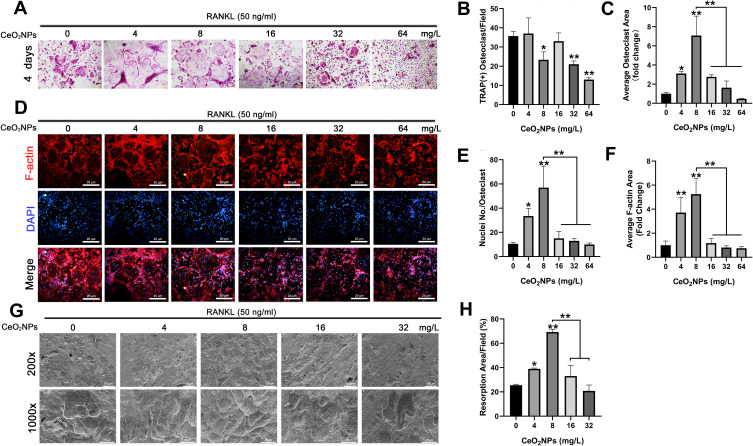

CeO2NPs Modulate RANKL-Dependent Osteoclast Formation in a Bidirectional Manner

The effects of CeO2NPs on osteoclast formation were measured using the TRAP staining assay. After pretreatment with various concentrations (0, 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64 mg/L) of CeO2NPs, BMMs were cultured in the presence of M-CSF (30 ng/mL) and RANKL (50 ng/mL) for 4 days until TRAP staining. Figure 3A demonstrates that CeO2NPs treatment facilitated RANKL-dependent osteoclast formation at lower concentrations (4.0 mg/L to 8.0 mg/L), with an increased average size of the formed osteoclasts. However, at higher concentrations (16.0 mg/L to 64 mg/L), we observed inhibitory effects of CeO2NPs on osteoclast formation. The average number and area were also counted. Figure 3B and C show that the average number of multinucleated osteoclasts (>3 nuclei) per field increased from 35.6 at 4 mg/L and slightly decreased to 23.3 at 8 mg/L, followed by a declining trend from 33 to 14.6 when the CeO2NPs concentration increased from 16 mg/L to 64 mg/L. Additionally, CeO2NPs increased the size of differentiated OCs from 1.0-fold (control) to 2.3-fold (4 mg/L) and 6.20-fold (8 mg/L) and subsequently inhibited the size of OCs from 2.4-fold (16 mg/L) to 1.4-fold (32 mg/L) and 0.42-fold (64 mg/L) in a dose-dependent manner. These results demonstrate that CeO2NPs modulate RANKL-dependent osteoclast formation in a bidirectional manner.

Figure 3.

CeO2NPs modulate RANKL-dependent osteoclastogenesis in vitro by facilitating osteoclast formation at lower concentrations and inhibiting osteoclastogenesis at higher concentrations.

Notes: (A) Representative images of TRAP staining. BMMs were stimulated with RANKL (50 ng/mL) for 4 days in the absence or presence of various concentrations of CeO2NPs. Scale bar = 8 µM. (B) Quantification of TRAP-positive multinucleated osteoclasts that were treated with different concentrations of CeO2NPs for 4 days. (C) Quantification of the average area of TRAP-positive multinucleated osteoclasts in different groups. (D) Representative images of increased F-actin ring formation in osteoclasts that were treated with lower concentrations of CeO2NPs (4 and 8 mg/L) and impaired F-actin ring formation in osteoclasts that were treated with higher concentrations of CeO2NPs (16, 32, and 64 mg/L). Scale bar = 20 µM. (E) Quantification of the number of nuclei per osteoclast. (F) Quantification of the relative area of the F-actin ring of osteoclasts. (G) Representative SEM images of bone resorption after treatment with different concentrations of CeO2NPs for 14 days. Scale bar = 100 µM (H) Quantification of resorbed bone slice area in the different groups. All bar graphs are presented as the mean ± SD. *Indicates p<0.05 compared with the control group (0 mg/L, RANKL+). **Indicates p<0.01 compared with the control group (0 mg/L, RANKL+).

Bidirectional Effects of CeO2NPs on Actin Ring Formation

Under RANKL stimulation, BMMs differentiate into mature OCs, which are able to resorb bone matrix. We investigated the effects of CeO2NPs at the former concentrations on actin ring formation. As shown in Figure 3D–F, stimulation with CeO2NPs increased the average area of actin rings from 1.0-fold (control) to 1.8-fold (4 mg/L) and 3.1-fold (8 mg/L), which subsequently declined from 0.7-fold (16 mg/L) to 0.5-fold (32 mg/L) and 0.4-fold (32 mg/L). Similarly, the average number of nuclei per OC also peaked at 56.97 (8 mg/L) and declined to 9.94 (64 mg/L). Collectively, these results indicate that CeO2NPs modulates mature OC formation in a bidirectional manner.

CeO2NPs Modulated Osteoclast Resorptive Activity

To further validate the effects of CeO2NPs on the bone resorptive activity of OCs, we performed bone resorption tests using bovine bone slices. In contrast to the resorptive function of the control, the bone resorptive function of OCs was enhanced at lower concentrations (from 4 mg/L to 8 mg/L) of CeO2NPs, whereas higher concentrations (from 16 mg/L to 64 mg/L) led to decreased resorptive function (Figure 3G). Resorption area analysis (Figure 3H) showed that the percentage resorption area per field increased from 25.48% ± 0.79% (0 mg/L) to 38.94% ± 0.66% (4 mg/L) and 69.23% ± 2.36% (8 mg/L) and then declined to 33.01% ± 8.72% (16 mg/L) and 20.85% ± 4.81% (32 mg/L). These results further confirmed that CeO2NPs modulate the resorptive activity of OCs in a bidirectional manner.

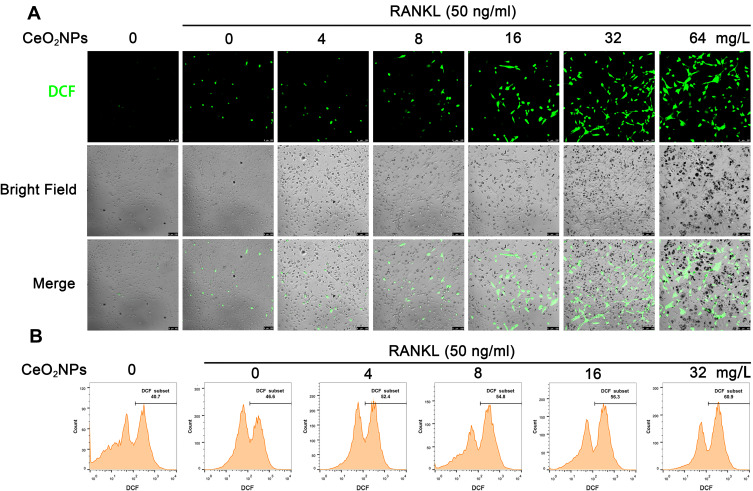

CeO2NPs Increased ROS Levels in BMMs During Osteoclastogenesis

According to previous studies, ROS play a crucial role in the initiation of osteoclastogenesis; ROS act as intracellular messenger molecules to activate the downstream MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways and then initiate osteoclastogenesis. CeO2NPs are well known for their ROS modulating ability. To verify the ROS modulation effects of CeO2NPs in osteoclastogenesis, we determined the ROS level in BMMs under the stimulation of RANKL and various concentrations of CeO2NPs using a sensitive intracellular ROS probe, DCFH-DA. As shown in Figure 4A, the average ROS level of BMMs that were pretreated with different concentrations of CeO2NPs (0, 8, 16, 32, and 64 mg/L) increased in a dose-dependent manner after treatment with RANKL for 2 days. Similar results were found when we performed intracellular ROS measurements using flow cytometry in BMMs that were treated with RANKL for 10 min (Figure 4B). The increasing dose of CeO2NPs increased the percentage of the high ROS subset of BMMs from 46.7% to 61.0% after stimulation with RANKL. Collectively, these results indicate that CeO2NP treatment increases the intracellular ROS level of BMMs in the early and middle stages of RANKL-dependent osteoclastogenesis.

Figure 4.

CeO2NP stimulation increases the intracellular ROS level in BMMs during osteoclastogenesis.

Notes: (A) Representative confocal images of RANKL-induced intracellular ROS generation in BMMs with or without pretreatment with CeO2NPs. BMMs were pretreated with or without CeO2NPs and stimulated with or without RANKL for 2 days. BMMs were probed with the ROS-sensitive probe DCFH-DA. Intracellular ROS were detected in the form of fluorescent DCF. Scale bar = 100 µM. (B) Intracellular ROS generation in BMMs with or without pretreatment with CeO2NPs was detected by flow cytometry. BMMs were pretreated with various concentrations of CeO2NPs, dyed with DCFH-DA, removed from the culture plate with 0.25% trypsin and stimulated with or without RANKL for 10 min before flow cytometry analysis.

CeO2NPs Modulate the Acidification Process in OCs

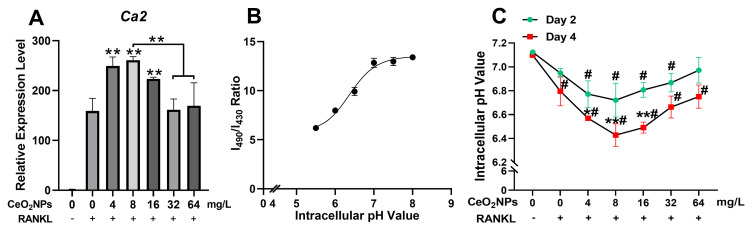

During osteoclastogenesis, RANKL stimulation upregulates the gene expression of carbonic anhydrase II (CAII), which produces a large amount of H+ and decreases the pH of the cytoplasm of OCs. H+ is further pumped into the resorption compartment to maintain an acidic environment, which is vital for the resorption function of osteoclasts.31 Moreover, an acidic cellular environment induces the production of ROS by CeO2NPs.16,33,34,41 We detected the acidification-related gene expression of CAII by qPCR (Figure 5A). CAII was significantly upregulated by lower concentrations of CeO2NPs (4, 8, and 16 mg/L). We also measured the intracellular pH of BMMs and OCs under stimulation with various concentrations of CeO2NPs and RANKL on day 2 and day 4 (Figure 5B and C). The pH of BMMs on day 2 showed a decreasing trend when the concentrations of CeO2NPs increased from 0 to 8 mg/L and then steadily rose when concentrations of CeO2NPs increased from 16 to 64 mg/L. On the 4th day, OCs that were stimulated with 4, 8, and 16 mg/L CeO2NPs showed significantly lower pH values (6.569 ± 0.01, 6.428 ± 0.10, 6.49 ± 0.05) compared with those of the vehicle group (6.795 ± 0.12). However, for the 32 and 64 mg/L CeO2NP groups, the pH of OCs increased compared with that of the 8 mg/L group. In conclusion, CeO2NPs modulate the acidification of OCs in a bidirectional manner. Relatively lower concentrations of CeO2NPs (4, 8, and 16 mg/L) significantly facilitate acidification of BMMs and OCs during osteoclastogenesis, but this effect tended to diminish with a further increase in CeO2NP concentrations.

Figure 5.

CeO2NPs bidirectionally modulated intracellular acidification of BMMs during RANKL-dependent osteoclastogenesis.

Notes: (A) qPCR analysis of the gene expression of carbonic anhydrase 2 relative Beta actin in BMMs that were stimulated with or without RANKL in the presence of various concentrations of CeO2NPs. (B) Calibration plot that correlates the 490 nm/430 nm fluorescence emission intensity ratio of BCECF-AM upon excitation at 530 nm to pH. (C) Intracellular pH of BMMs and OC were stimulated with various concentrations of CeO2NPs and RANKL for 2 days and 4 days. All bar and line graphs are presented as the mean ± SD. #Indicates p<0.05 compared with the control group (0 mg/L, RANKL-). *Indicates p<0.05 compared with the vehicle group (0 mg/L, RANKL+). **Indicates p<0.01 compared with the vehicle group (0 mg/L, RANKL+).

Bidirectional Regulation of Osteoclast-Specific Gene Expression and Signaling Pathways by CeO2NPs

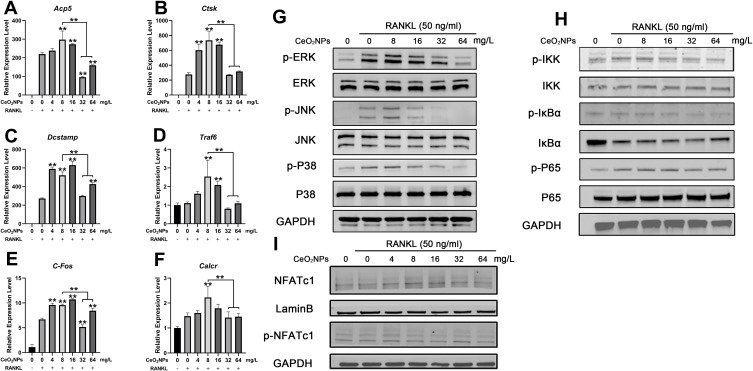

To further investigate the mechanisms of the bidirectional regulatory effects of CeO2NPs on osteoclastogenesis, we determined the expression levels of several osteoclast-specific genes using qRT-PCR and detected activation of the osteoclastogenesis-related signaling pathway by Western blotting. As shown in Figure 6A, expression of Acp5, Ctsk, DCSTAMP, Traf6, C-Fos, and Calcr in BMMs was upregulated in the presence of RANKL. These genes were further upregulated by lower concentrations of CeO2NPs compared with those of the vehicle group, peaking at 8 mg/L. With increasing in CeO2NPs concentrations, nearly all related genes were downregulated in comparison with those in the 8 mg/L CeO2NPs group.

Figure 6.

CeO2NPs modulate osteoclast-specific gene expression via up- or downregulating the MAPK pathway, NF-κB pathway, and Nfatc1 signaling in a concentration-dependent manner.

Notes: (A–F) qPCR analysis of expression of the osteoclast-specific genes Acp5, Ctsk, Dcstamp, Traf6, C-fos, and Calcr relative to Beta-actin in BMMs that were stimulated with RANKL for 4 days in the presence of various concentrations of CeO2NPs (n=3 per group). (G and H) Western blot analysis of the MAPK and NF-κB pathways. BMMs were pretreated with different concentrations of CeO2NPs for 24 h before stimulation with RANKL for 20 min. (I) Western blot of the translocation of dephosphorylated Nfatc1 into the nuclei of BMMs. BMMs were pretreated with different concentrations of CeO2NPs for 24 h before stimulation with RANKL for 40 min. All bar graphs are presented as the mean ± SD. **Indicates p<0.01 compared with the vehicle group (0 mg/L, RANKL+).

Activation of the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways is closely related to RANKL-dependent osteoclastogenesis. Therefore. We pretreated BMMs with various concentrations of CeO2NPs for 24 h and then determined the expression of IKKα, IKBα, and P65 of the NF-κB signaling pathway and ERK, JNK, and P38 of the MAPK signaling pathway after stimulating pretreated BMMs with RANKL for 20 min (Figure 6B and C). The results indicated that phosphorylation of IKKα, IKBα, and P65 relative to total IKKα, IKBα, and P65 and phosphorylation of ERK, JNK, and P38 relative to total ERK, JNK, and P38 increased at 4 mg/L, peaked at 8 mg/L, and subsequently declined from 16 mg/L to 64 mg/L. These results were consistent with the former characterization of OC formation, suggesting that the MAPK and NF-κB pathways were both engaged in the CeO2NP-mediated bidirectional modulation of osteoclast activation. In addition, the expression level of a master osteoclast-related transcription factor, Nfatc1, in BMMs that were stimulated with RANKL for 40 min (Figure 6D) was determined. We found that expression of the active nonphosphorylated form of Nfatc1 increased in the presence of RANKL and treatment with CeO2NPs at concentrations no greater than 8 mg/L and subsequently decreased with CeO2NP treatment at concentrations from 16 mg/L to 64 mg/L. Collectively, these results revealed the underlying mechanisms during the bidirectional modulation of osteoclasts by CeO2NPs.

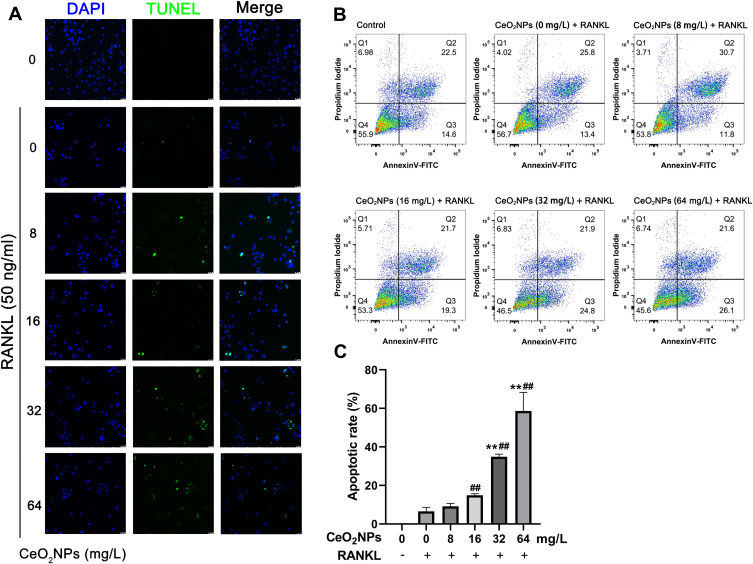

CeO2NPs Facilitated Apoptosis of BMMs During Osteoclastogenesis

The abovementioned results suggested that CeO2NPs dose-dependently enhanced intracellular ROS levels in BMMs, while overloading intracellular ROS may lead to increased apoptosis and dysfunction of BMMs. To validate this, TUNEL staining and annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide (PI) double staining were performed to detect BMM apoptosis after treatment with various concentrations of CeO2NPs (0, 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64 mg/L) with or without RANKL for 2 days. As shown in Figure 7A and C, CeO2NPs increased the number of apoptotic cells in a dose-dependent manner. Few apoptotic cells were observed in the 0, 4, and 8 mg/L CeO2NP groups, whereas more apoptotic cells were detected in the high concentration groups (16, 32, and 64 mg/L). Flow cytometry analysis of Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining indicated that early apoptosis and total apoptosis rates of BMMs increased as the concentrations of CeO2NPs increased.

Figure 7.

CeO2NPs increased the apoptosis of BMMs during RANKL-dependent osteoclastogenesis.

Notes: (A) Representative confocal images of the TUNEL assay of BMMs that were pretreated with different concentrations of CeO2NPs (0, 8, 16, 32, and 64 mg/L) for 24 h and stimulated with or without RANKL for two days. Scale bar = 25 µM. (B) Representative flow cytometry images of Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining of BMMs that were pretreated with different concentrations of CeO2NPs (0, 8, 16, 32, and 64 mg/L) for 24 h and stimulated with or without RANKL for two days. (C) Quantification of the apoptotic rate of BMMs (TUNEL-positive nuclei relative to total nuclei). All bar graphs are presented as the mean ± SD. ##Indicates p<0.01 compared with the control group (0 mg/L, RANKL-). **Indicates p<0.01 compared with the vehicle group (0 mg/L, RANKL+).

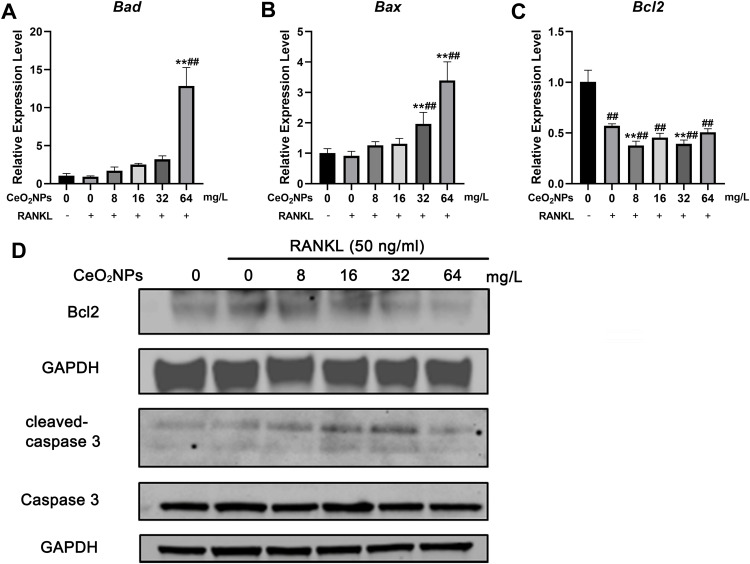

These results were also confirmed by qRT-PCR (Figure 8A) and Western blotting (Figure 8B). The expression of proapoptotic Bad and Bax was upregulated, especially at high CeO2 concentrations (32 and 64 mg/L), and the antiapoptotic gene Bcl-2 was downregulated as the concentration of CeO2NPs increased. Western blot analysis also showed that the expression of Bcl2 decreased and the proapoptotic protein cleaved caspase-3/caspase-3 ratio increased as the concentration of CeO2NPs increased. These results suggest that high concentrations of CeO2NPs lead to cell apoptosis and dysfunction, thus inhibiting osteoclast formation.

Figure 8.

Effects of CeO2NPs on apoptosis-related gene expression.

Notes: (A–C) qPCR analysis of expression of apoptosis-related genes, including Bax, Bad, and Bcl2. (D) Western blot analysis of Bcl2, cleaved caspase 3 and caspase 3. BMMs were pretreated with various CeO2NPs (8, 16, 32, and 64 mg/L) for 24 h and then stimulated with or without RANKL for 2 days. All bar graphs are presented as the mean ± SD. ##Indicates p<0.01 compared with the control group (0 mg/L, RANKL-). **Indicates p<0.01 compared with the vehicle group (0 mg/L, RANKL+).

Discussion

Recent years have witnessed the rapid development of nanomaterial applications in medicine. CeO2NPs are among the first batch of nanomaterials and have been explored in medical use. CeO2NPs perform catalase-mimetic, superoxide dismutase-mimetic and peroxidase-mimetic activities in biological environments. Their robust, stable, regenerative and multiple enzymatic reactivities have been extensively tested in various types of cells and several pathological processes, such as neural injury, infection, systemic inflammation, cancer, and bone tissue engineering.10,41-43 Generally, CeO2NPs are regarded as potent ROS scavengers that protect cells from oxidative stress damage. Extensive studies have explored the effects of CeO2NPs on the viability of BMSCs, osteoblasts, chondrocytes and BMSCs during osteoblastic differentiation. Some reports indicated that cell viability and osteoblastic differentiation were enhanced by CeO2NPs.18–22,44,45 However, these studies indicated that CeO2NPs increase ROS production in acidic intercellular environments and exhibit bidirectional regulatory effects on osteoclast differentiation, which suggests that the application of CeO2NPs should take into account the cellular environment and dose-dependent effects.

CeO2NPs with a diameter of 20 nm were used in this study. According to previous studies, surface valence state and size are important factors in manipulating intracellular catalytic activity. CeO2NPs with a higher Ce4+/Ce3+ surface valence ratio usually showed catalase-mimetic activity, which depletes intracellular H2O2 and protects cells from oxidative stress.5,6 In contrast, CeO2NPs with a higher surface Ce3+/Ce4+ ratio tended to show SOD-mimetic activities in the intracellular microenvironment and catalyze the disproportionate reaction of O2- to produce excessive H2O2, which harms cell viability and leads to cell dysfunction.5,8,46,47 The XPS results revealed that the relative Ce4+ content was 73% and that of Ce3+ was 27%. The surface oxygen content was approximately 19.67%. The diameter of CeO2NPs was approximately 20 nm, which was suitable for cell internalization, which was further validated by TEM observations. In addition, before cell experiments, we used ESR to determine the antioxidative effects of CeO2NPs in acellular environments by measuring O2- and H2O2 generated by hypoxanthine and xanthine oxidase. Our results indicated that the CeO2NPs used in this study efficiently reduced the production of O2- and H2O2.

Within the bone marrow, macrophages proliferate and fuse into giant multinucleated mature osteoclasts, which are responsible for bone resorption and bone remodeling.48 First, we tested the cytotoxic effects of CeO2NPs on BMMs and found that BMM viability was not obviously impaired in the presence of up to 64 mg/L CeO2NPs after two days of culture. Therefore, we chose concentrations of CeO2NPs below 64 mg/L to perform subsequent experiments. Interestingly, although the number of OCs per field decreased in the 8 mg/L group compared with that of the control group, which may be attributed to the extensive fusion of BMMs into more giant OCs at 8 mg/L, the results from the osteoclast formation assay and actin ring formation assay indicated that lower concentrations of CeO2NPs facilitated more giant osteoclast formation. However, this facilitating effect reversed the inhibitory effect, as demonstrated by the decreased osteoclast number and area with increasing concentrations of CeO2NPs. This intriguing result showed the bidirectional effects of CeO2NPs on osteoclast formation and bone resorption.

The MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways are two classical signaling pathways in the activation of osteoclasts.48 Under RANKL stimulation, TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (Traf6) is activated and then activates the downstream protein kinase TAK1, which subsequently phosphorylates ERK and IKKα. Phosphorylated ERK and IKKα further activate the MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways and finally activate the essential transcription factor Nfatc1 for osteoclastogenesis.49 ROS directly or indirectly activate the MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways.50–58 Previous studies demonstrated that H2O2 induces reversible oxidation of cysteine residues of IKKα/β and phosphorylation of IκBα, which subsequently activates the NF-κB signaling pathway.54,55 ROS also induce the dislocation of Trx from apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1), which then phosphorylates JNK and p38 and finally leads to activation of the MAPK signaling pathway.56–58 Our data showed that pretreatment with lower CeO2NPs (8 mg/L) enhanced RANKL-induced phosphorylation of ERK, JNK, and P38, thus achieving its facilitating effects, whereas the phosphorylation of ERK, JNK, and P38 decreased slightly as the CeO2NP concentrations further rose. Similar trends were also observed in NF-κB activation. Nfatc1 is a master transcription factor that regulates downstream osteoclast-specific gene expression. The Western blotting results showed that lower CeO2NP concentrations (4 and 8 mg/L) increased the dephosphorylation of Nfatc1 and facilitated its nuclear translocation, while higher CeO2NP concentrations (16 and 64 mg/L) decreased activation of Nfatc1. This result demonstrated that CeO2NPs generate ROS, activate the downstream MAPK and NF-κB pathways and finally activate Nfatc1 or directly interact with Nfatc1 in the early stage of osteoclastogenesis. We also measured the downstream genes that are regulated by Nfatc1, including Acp5, Ctsk, DCSTAMP, Traf6, C-Fos, and Calcr, and showed an increasing trend in the expression of these genes in the lower CeO2NP concentration groups (4,8 mg/L) and a decreasing trend in expression in the higher CeO2NP concentration group. These results also validated the bidirectional modulatory effects of CeO2NPs on osteoclast activation.

Next, explored the underlying mechanism of the bidirectional effects of CeO2NPs on osteoclastogenesis. RANKL induces intracellular ROS production in BMMs. Hence, we determined ROS production using DCFH-DA as an intracellular ROS probe. Measurement of the ROS-positive cell ratio indicated that intracellular ROS production in BMMs on day 0 and day 2 was increased by RANKL and further enhanced by CeO2NPs in a dose-dependent manner. This oxidative effect of CeO2NPs contradicts our previous ROS scavenging results in the acellular oxidative system. A distinct characteristic of BMMs and OCs is their abundance of acidic lysosomes, which are responsible for antigen phagocytosis and bone resorption. It has been reported that CeO2NPs facilitate ROS production in acidic cellular microenvironments, such as various cancer cells. Because of the Warburg effect, cancer cells tend to generate energy through glycolysis even in an abundant O2 environment and produce much lactate, resulting in a comparatively acidic cytoplasm. Wason MS. found that CeO2NPs enhanced ROS production in pancreatic cancer cells and increased the sensitization of pancreatic cancer to radiation therapy.16 Researchers attribute the oxidative effects of CeO2NPs in acidic environments to protons that block the redox cycling from Ce3+ to Ce4+, resulting in excessive toxic H2O2 production in cells. Our TEM results showed that some CeO2NPs were distributed in lysosomes after internalization by BMMs. We attribute the increase in early ROS production in BMMs that were stimulated by RANKL to the intracellular distribution of CeO2NPs in acidic lysosomes. Moreover, with activation of osteoclastogenesis by RANKL, carbonic anhydrase was highly upregulated in BMMs and further catalyzed the production of protons, which were then pumped into the acidic compartment to form the acidic bone resorption environment (pH: 4.7–6.8).59 Our qPCR results showed that carbonic anhydrase II was significantly upregulated in the lower CeO2NP concentration groups compared with those of the vehicle group. In addition, intracellular pH measurements suggested that the intracellular pH of OCs that were treated with lower concentrations of CeO2NPs was significantly lower than that of OCs in the vehicle groups, which could account for the increase in intracellular ROS in OCs during the middle and late stages of osteoclastogenesis. In conclusion, intracellular distribution in lysosomes and acidification triggered by RANKL stimulation are initiating factors that contribute to increased ROS production by CeO2NPs. ROS production increased by CeO2NPs further facilitated the osteoclastogenesis and acidification process of OCs, which further increased the production of ROS by CeO2NPs in a positive feedback manner. Although previous ROS measurements suggested that CeO2NPs dose-dependently increase intracellular ROS production in BMMs under the stimulation of RANKL, higher concentrations of CeO2NPs inhibited osteoclastogenesis compared with lower concentrations of CeO2NPs. We hypothesized that excessive CeO2NP internalization and subsequent ROS production leads to disturbances in cell structure and cell dysfunction and ultimately, cell apoptosis. The TUNEL assay showed that CeO2NPs resulted in late-stage apoptosis of BMMs in a dose-dependent manner. This proapoptotic effect was further confirmed by Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining, which indicated that higher concentrations of CeO2NPs facilitate not only late-stage apoptosis but also early-stage apoptosis of BMMs during RANKL-dependent osteoclastogenesis. We then measured the expression of several classic genes that are related to apoptosis through qPCR and Western blotting. The results indicated that a high (64 mg/L) concentration of CeO2NP significantly increased the expression of Bax at the transcriptional level and that the expression of Bcl2 was decreased at both the transcriptional and protein levels. The expression of cleaved caspase-3/caspase-3 was upregulated in the 16 and 32 mg/L concentration groups. These results indicate that high CeO2NP treatment resulted in cell apoptosis during osteoclastogenesis. We hypothesize that the different outcomes of the CCK-8 and apoptosis experiments can be accounted for by the acidification and ROS production triggered by RANKL. Enhanced ROS production by CeO2NPs cooperates with the acidification of BMMs during osteoclastogenesis, as we observed in the 8 mg/L group, leading to the upregulated expression of carbonic anhydrase and the strongest osteoclast formation. Importantly, in the highest CeO2NP concentration group (64 mg/L), most gene expression was inhibited, which might be due to excessive internalization of CeO2NPs disrupting the normal gene expression pattern of BMMs. This was again confirmed by TEM observation, showing the absence of normal organelle structure in BMMs that were filled with CeO2NPs. We also found that CeO2NPs were internalized into the nucleus, which might disrupt normal cell metabolism and gene expression.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that CeO2NPs with a comparatively increased surface Ce4+/Ce3+ ratio bidirectionally modulate RANKL-dependent osteoclastogenesis by enhancing intracellular ROS production, which enhances activation of the MAPK and NF-κB pathways, followed by activation of Nfatc1 and downstream osteoclastogenesis-related gene expression at lower CeO2NP concentrations. The cellular distribution of CeO2NPs in lysosomes and increasing acidification of cell plasma may be the factors that initiate and facilitate increased intracellular ROS production by CeO2NPs. In contrast, increased concentrations of CeO2NPs led to the obvious disturbance of cell structure and cell apoptosis. These findings reminded us that the use of CeO2NPs as drug delivery vehicles or antioxidant components needs to be given more attention regarding the cellular environment and dose-dependent effects.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Shanghai Science and Technology Development Fund (18DZ2291200, 18441902700) and National Natural Science Foundation for Young Scientist of China (81902230).

Ethics Approval

All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Animal Ethical Committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital. The approval number is SH9H-2019-A719-1.

Author Contributions

K.Y. and J.M. contributed equally to this work. All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Dutta P, Pal S, Seehra MS, Shi Y, Eyring EM, Ernst RD. Concentration of Ce3+ and oxygen vacancies in cerium oxide nanoparticles. Chem Mater. 2006;18(21):5144–5146. doi: 10.1021/cm061580n [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Celardo I, Pedersen JZ, Traversa E, Ghibelli L. Pharmacological potential of cerium oxide nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2011;3(4):1411–1420. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00875c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mullins DR. The surface chemistry of cerium oxide. Surf Sci Rep. 2015;70(1):42–85. doi: 10.1016/j.surfrep.2014.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deshpande S, Patil S, Kuchibhatla SV, Seal S. Size dependency variation in lattice parameter and valency states in nanocrystalline cerium oxide. Appl Phys Lett. 2005;87(13):133113. doi: 10.1063/1.2061873 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pirmohamed T, Dowding JM, Singh S, et al. Nanoceria exhibit redox state-dependent catalase mimetic activity. Chem Commun (Camb). 2010;46(16):2736–2738. doi: 10.1039/b922024k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicolini V, Gambuzzi E, Malavasi G, et al. Evidence of catalase mimetic activity in Ce(3+)/Ce(4+) doped bioactive glasses. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119(10):4009–4019. doi: 10.1021/jp511737b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, He X, Yin JJ, et al. Acquired superoxide-scavenging ability of ceria nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54(6):1832–1835. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korsvik C, Patil S, Seal S, Self WT. Superoxide dismutase mimetic properties exhibited by vacancy engineered ceria nanoparticles. Chem Commun (Camb). 2007;(10):1056–1058. doi: 10.1039/b615134e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tian Z, Li J, Zhang Z, Gao W, Zhou X, Qu Y. Highly sensitive and robust peroxidase-like activity of porous nanorods of ceria and their application for breast cancer detection. Biomaterials. 2015;59:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.04.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selvaraj V, Nepal N, Rogers S, et al. Inhibition of MAP kinase/NF-kB mediated signaling and attenuation of lipopolysaccharide induced severe sepsis by cerium oxide nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2015;59:160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pagliari F, Mandoli C, Forte G, et al. Cerium oxide nanoparticles protect cardiac progenitor cells from oxidative stress. ACS Nano. 2012;6(5):3767–3775. doi: 10.1021/nn2048069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon HJ, Cha MY, Kim D, et al. Mitochondria-targeting ceria nanoparticles as antioxidants for alzheimer’s disease. ACS Nano. 2016;10(2):2860–2870. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b08045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu L, Liu G, Wang W, et al. Cyclodextrin-modified CeO(2) nanoparticles as a multifunctional nanozyme for combinational therapy of psoriasis. Int J Nanomedicine. 2020;15:2515–2527. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S246783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zand Z, Khaki PA, Salihi A, et al. Cerium oxide NPs mitigate the amyloid formation of α-synuclein and associated cytotoxicity. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:6989–7000. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S220380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alili L, Sack M, von Montfort C, et al. Downregulation of tumor growth and invasion by redox-active nanoparticles. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19(8):765–778. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wason MS, Colon J, Das S, et al. Sensitization of pancreatic cancer cells to radiation by cerium oxide nanoparticle-induced ROS production. Nanomedicine. 2013;9(4):558–569. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renu G, Rani VVD, Nair SV, Subramanian KRV, Lakshmanan V-K. Development of cerium oxide nanoparticles and its cytotoxicity in prostate cancer cells. Adv Sci Lett. 2012;6(1):17–25. doi: 10.1166/asl.2012.3312 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Wen J, Li B, et al. Valence state manipulation of cerium oxide nanoparticles on a titanium surface for modulating cell fate and bone formation. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2018;5(2):1700678. doi: 10.1002/advs.201700678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li K, Xie Y, You M, Huang L, Zheng X. Plasma sprayed cerium oxide coating inhibits H2O2-induced oxidative stress and supports cell viability. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2016;27(6):100. doi: 10.1007/s10856-016-5710-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.You M, Li K, Xie Y, Huang L, Zheng X. The effects of cerium valence states at cerium oxide coatings on the responses of bone mesenchymal stem cells and macrophages. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2017;179(2):259–270. doi: 10.1007/s12011-017-0968-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li K, Yu J, Xie Y, You M, Huang L, Zheng X. The effects of cerium oxide incorporation in calcium silicate coating on bone mesenchymal stem cell and macrophage responses. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2017;177(1):148–158. doi: 10.1007/s12011-016-0859-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li K, Xie Y, You M, Huang L, Zheng X. Cerium oxide-incorporated calcium silicate coating protects MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells from H2O2-induced oxidative stress. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2016;174(1):198–207. doi: 10.1007/s12011-016-0680-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li K, Shen Q, Xie Y, You M, Huang L, Zheng X. Incorporation of cerium oxide into hydroxyapatite coating protects bone marrow stromal cells against H2O2-induced inhibition of osteogenic differentiation. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2018;182(1):91–104. doi: 10.1007/s12011-017-1066-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Labudzynskyi D, Zholobak N. Effects of cerium (IV) oxide nanoparticles on RAW 264.7 cells activity and RANKL-stimulated osteoclastogenesis. Conference paper presented at: Modern aspects of Biochemistry and Biotechnology; May 23; 2018; Kyiv. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee NK, Choi YG, Baik JY, et al. A crucial role for reactive oxygen species in RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation. Blood. 2005;106(3):852–859. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Callaway DA, Jiang JX. Reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress in osteoclastogenesis, skeletal aging and bone diseases. J Bone Miner Metab. 2015;33(4):359–370. doi: 10.1007/s00774-015-0656-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srinivasan S, Koenigstein A, Joseph J, et al. Role of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in osteoclast differentiation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1192(1):245–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05377.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agidigbi TS, Kim C. Reactive oxygen species in osteoclast differentiation and possible pharmaceutical targets of ROS-mediated osteoclast diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(14):3576. doi: 10.3390/ijms20143576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, Wang X, Vikash V, et al. ROS and ROS-mediated cellular signaling. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:4350965. doi: 10.1155/2016/4350965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibon E, Lu LY, Nathan K, Goodman SB. Inflammation, ageing, and bone regeneration. J Orthop Translat. 2017;10:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2017.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rousselle AV, Heymann D. Osteoclastic acidification pathways during bone resorption. Bone. 2002;30(4):533–540. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(02)00672-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asati A, Kaittanis C, Santra S, Perez JM. pH-tunable oxidase-like activity of cerium oxide nanoparticles achieving sensitive fluorigenic detection of cancer biomarkers at neutral pH. Anal Chem. 2011;83(7):2547–2553. doi: 10.1021/ac102826k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alpaslan E, Yazici H, Golshan NH, Ziemer KS, Webster TJ. pH-dependent activity of dextran-coated cerium oxide nanoparticles on prohibiting osteosarcoma cell proliferation. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2015;1(11):1096–1103. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asati A, Santra S, Kaittanis C, Nath S, Perez JM. Oxidase-like activity of polymer-coated cerium oxide nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48(13):2308–2312. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wason MS, Zhao J. Cerium oxide nanoparticles: potential applications for cancer and other diseases. Am J Transl Res. 2013;5(2):126–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patterson AL. The scherrer formula for X-ray particle size determination. Phys Rev. 1939;56(10):978–982. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.56.978 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou F, Mei J, Yuan K, Han X, Qiao H, Tang T. Isorhamnetin attenuates osteoarthritis by inhibiting osteoclastogenesis and protecting chondrocytes through modulating reactive oxygen species homeostasis. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(6):4395–4407. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Behbahan ISS, McBrian MA, Kurdistani SK. A protocol for measurement of intracellular pH. Bio-Protocol. 2014;4(2):e1027. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.1027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, Xiang L, Jiang X, et al. Investigation of bioeffects of G protein-coupled receptor 1 on bone turnover in male mice. J Orthop Translat. 2017;10:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2017.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mei J, Zhou F, Qiao H, Li H, Tang T. Nerve modulation therapy in gouty arthritis: targeting increased sFRP2 expression in dorsal root ganglion regulates macrophage polarization and alleviates endothelial damage. Theranostics. 2019;9(13):3707–3722. doi: 10.7150/thno.33908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao Y, Chen K, Ma J-L GF. Cerium oxide nanoparticles in cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:835–840. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S62057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naz S, Beach J, Heckert B, et al. Cerium oxide nanoparticles: a ‘radical’ approach to neurodegenerative disease treatment. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2017;12(5):545–553. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2016-0399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiang J, Li J, He J, et al. Cerium oxide nanoparticle modified scaffold interface enhances vascularization of bone grafts by activating calcium channel of mesenchymal stem cells. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(7):4489–4499. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b00158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Naganuma T, Traversa E. The effect of cerium valence states at cerium oxide nanoparticle surfaces on cell proliferation. Biomaterials. 2014;35(15):4441–4453. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li K, Shen Q, Xie Y, You M, Huang L, Zheng X. Incorporation of cerium oxide into hydroxyapatite coating regulates osteogenic activity of mesenchymal stem cell and macrophage polarization. J Biomater Appl. 2017;31(7):1062–1076. doi: 10.1177/0885328216682362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pulido-Reyes G, Rodea-Palomares I, Das S, et al. Untangling the biological effects of cerium oxide nanoparticles: the role of surface valence states. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):15613. doi: 10.1038/srep15613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen BH, Stephen Inbaraj B. Various physicochemical and surface properties controlling the bioactivity of cerium oxide nanoparticles. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2018;38(7):1003–1024. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2018.1426555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature. 2003;423(6937):337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature01658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kurotaki D, Yoshida H, Tamura T. Epigenetic and transcriptional regulation of osteoclast differentiation. Bone. 2020;138:115471. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moldogazieva NT, Mokhosoev IM, Feldman NB, Lutsenko SV. ROS and RNS signalling: adaptive redox switches through oxidative/nitrosative protein modifications. Free Radic Res. 2018;52(5):507–543. doi: 10.1080/10715762.2018.1457217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jung Y, Kim H, Min SH, Rhee SG, Jeong W. Dynein light chain LC8 negatively regulates NF-kappaB through the redox-dependent interaction with IkappaBalpha. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(35):23863–23871. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803072200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim HJ, Chang EJ, Kim HM, et al. Antioxidant alpha-lipoic acid inhibits osteoclast differentiation by reducing nuclear factor-kappaB DNA binding and prevents in vivo bone resorption induced by receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40(9):1483–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.10.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rezatabar S, Karimian A, Rameshknia V, et al. RAS/MAPK signaling functions in oxidative stress, DNA damage response and cancer progression. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(9):14951–14965. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lisse TS, Rieger S. IKKα regulates human keratinocyte migration through surveillance of the redox environment. J Cell Sci. 2017;130(5):975–988. doi: 10.1242/jcs.197343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takada Y, Mukhopadhyay A, Kundu GC, Mahabeleshwar GH, Singh S, Aggarwal BB. Hydrogen peroxide activates NF-kappa B through tyrosine phosphorylation of I kappa B alpha and serine phosphorylation of p65: evidence for the involvement of I kappa B alpha kinase and Syk protein-tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(26):24233–24241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212389200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kylarova S, Kosek D, Petrvalska O, et al. Cysteine residues mediate high-affinity binding of thioredoxin to ASK1. FEBS J. 2016;283(20):3821–3838. doi: 10.1111/febs.13893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katagiri K, Matsuzawa A, Ichijo H. Regulation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 in redox signaling. Methods Enzymol. 2010;474:277–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu J, Chang F, Li F, et al. Palmitate promotes autophagy and apoptosis through ROS-dependent JNK and p38 MAPK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;463(3):262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.05.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maeda H, Kowada T, Kikuta J. Real-time intravital imaging of pH variation associated with osteoclast activity. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12(8):579–585. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]