Abstract

Background

Quantitative blood flow (QBF) measurements that use pulsed-wave US rely on difficult-to-meet conditions. Imaging biomarkers need to be quantitative and user and machine independent. Surrogate markers (eg, resistive index) fail to quantify actual volumetric flow. Standardization is possible, but relies on collaboration between users, manufacturers, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Purpose

To evaluate a Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance–supported, user- and machine-independent US method for quantitatively measuring QBF.

Materials and Methods

In this prospective study (March 2017 to March 2019), three different clinical US scanners were used to benchmark QBF in a calibrated flow phantom at three different laboratories each. Testing conditions involved changes in flow rate (1–12 mL/sec), imaging depth (2.5–7 cm), color flow gain (0%–100%), and flow past a stenosis. Each condition was performed under constant and pulsatile flow at 60 beats per minute, thus yielding eight distinct testing conditions. QBF was computed from three-dimensional color flow velocity, power, and scan geometry by using Gauss theorem. Statistical analysis was performed between systems and between laboratories. Systems and laboratories were anonymized when reporting results.

Results

For systems 1, 2, and 3, flow rate for constant and pulsatile flow was measured, respectively, with biases of 3.5% and 24.9%, 3.0% and 2.1%, and −22.1% and −10.9%. Coefficients of variation were 6.9% and 7.7%, 3.3% and 8.2%, and 9.6% and 17.3%, respectively. For changes in imaging depth, biases were 3.7% and 27.2%, −2.0% and −0.9%, and −22.8% and −5.9%, respectively. Respective coefficients of variation were 10.0% and 9.2%, 4.6% and 6.9%, and 10.1% and 11.6%. For changes in color flow gain, biases after filling the lumen with color pixels were 6.3% and 18.5%, 8.5% and 9.0%, and 16.6% and 6.2%, respectively. Respective coefficients of variation were 10.8% and 4.3%, 7.3% and 6.7%, and 6.7% and 5.3%. Poststenotic flow biases were 1.8% and 31.2%, 5.7% and −3.1%, and −18.3% and −18.2%, respectively.

Conclusion

Interlaboratory bias and variation of US-derived quantitative blood flow indicated its potential to become a clinical biomarker for the blood supply to end organs.

© RSNA, 2020

Online supplemental material is available for this article.

See also the editorial by Forsberg in this issue.

Summary

Volume flow estimated across flow, depth and stenosis tests was accurate (11.5% mean bias) and reproducible (10.5% reproducibility error) in this interlaboratory study.

Key Results

■ Volume flow estimated by three-dimensional (3D) color flow US was accurate (11.5% mean bias) and reproducible (10.5% mean standard error) in our interlaboratory study.

■ This method required neither angle correction nor reliance on spatial symmetries and yielded volume flow from 3D color flow scans that cross-sectionally intersected the flow lumen with the lateral elevational constant depth plane.

Introduction

Blood flow is critical to organ and tissue perfusion but is difficult to measure noninvasively and inexpensively. Accurate blood flow measurement has the potential to fundamentally change organ assessment and treatment monitoring, but current methods have substantial limitations. The Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance was created by the Radiological Society of North America and includes researchers, health care professionals, and industry to positively impact health care by improving current biomarkers and investigating new ones. Flow imaging is well established by using US color flow and spectral Doppler but it is predominantly qualitative. Flow is either differentiated as no, low, moderate, or high flow, or described by surrogate indexes (eg, resistive index, pulsatility index, or velocity) (1,2). Surrogates may have diagnostic value, but do not measure actual flow in volume per unit time.

True sonographic flow measurement is rarely used clinically because of reliability issues and cumbersome implementation. Gill et al (3,4) found that spectral Doppler measurements in fetal veins (7-mm diameter) yielded a 14% error. Holland et al (5) concluded that spectral Doppler pulsatile flow estimations lead to 50% and 17% error in 3.2- and 12.7-mm diameter vessels, respectively. A study by Theodoraki et al (6) exemplified the underlying consequences. In that study, portal vein flow and velocity were assessed before cardiac operation and on postoperative days 1 and 7. The average coefficient of variation for these was 16.1%, somewhat smaller than the average pairwise time differences of 25.2%. Portal vein volume flow was measured with an average coefficient of variation of 32.4%, but average pairwise time difference was 11.0%. Despite these difficulties, there are persistent attempts to use volume flow clinically (obstetrics applications [7], portal vein applications [8], and cardiac output [9]).

The notable exception is the sonographic evaluation of hemodialysis arteriovenous fistulas and arteriovenous grafts. Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative practice guidelines include hemodialysis arteriovenous fistula flow to assess hemodialysis arteriovenous fistula maturation (10,11), and Robbin et al (12,13) found US effective in this context. Three-dimensional (3D) US has potential for quantitative blood flow (QBF) imaging by providing a rapid, less technically challenging examination, with greater accuracy. Promising initial studies (14–24) led to a Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance subcommittee and enabled the design and execution of our current study. Here we test the hypotheses that 3D color flow could quantify blood flow independent of (1) user and (2) US system. To this end, we measured flow in a calibrated phantom and assessed accuracy under relevant flow rates, measurement depths, varied user (sonographer) factors, and alterations in flow past a stenosis.

Materials and Methods

Canon Medical Systems (Tustin, Calif), GE Healthcare (Milwaukee, Wis), and Philips Healthcare (Bothell, Wash) provided clinical scanners free of charge. Data collection was performed by seven authors (J.A.Z., J.G., M.E.L, M.F.B., M.L.R., S.C., S.Z.P., and T.N.E.). Control of data inclusion and data processing was performed by O.D.K. The flow phantom was created by C.B. (an industry expert for US phantoms). Discussions concerning study design, data collection, and data processing were by all coauthors. J.B.F., J.M.R., O.D.K., P.L.C., and S.Z.P. are Doppler imaging experts. J.A.Z., M.F.B., and S.C. are biomedical engineering and US imaging experts. A.M. and T.N.E. are industry experts for US imaging. J.G., J.M.R., M.E.L., and M.L.R. are clinical radiologists with US expertise. N.O. is an expert for statistical data analysis. No human participants or animals were used in our study.

Three-dimensional Color Flow–based QBF

Our published method (18) of QBF is on the basis of Gauss divergence theorem, and is independent of Doppler angle, lumen diameter, flow velocity profile, and angle correction. It uses 3D color flow and power information on the on-screen lateral elevational constant depth plane (a general 3D surface; hereafter, c-plane) of a 3D volume acquisition as detailed in Appendix E1 (online). Three commercially available clinical US scanners, some with software modifications for data access, were used in our study. These were an Aplio i800 (Canon Medical Systems) with a mechanically swept PVT-675MVL probe, Logiq LE9 (GE Healthcare) with a mechanically swept RSP6–16 probe, and an Epiq 7 (Philips Healthcare) with an X6-1 two-dimensional matrix array. Per Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance convention, the scanner associated results are anonymized. These companies provided color flow velocity, color flow power (decompressed), and scan geometry. The tube lumen was placed in the center of the 3D volume (cube with 2-cm edges). Nonflow background in the phantom, approximately 9–10-lm cross sections by area, was included in the scan volume lateral-elevational constant depth c-plane.

Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance Flow Phantom

A flow phantom (HE Gel; Gammex, Middleton, Wis) was provided that was customized to specifications from this committee (28-cm height × 30.5-cm width × 22-cm depth; sound speed, 1540 m/sec ± 10 [standard deviation]; and attenuation, 0.5 dB/MHz/cm; Fig 1). Additional specifications are provided in Appendix E1 (online).

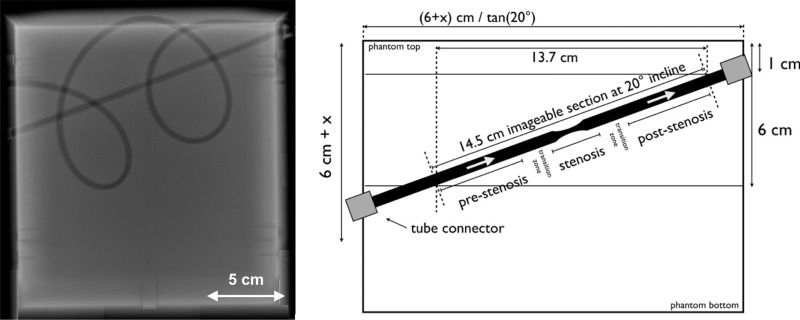

Figure 1:

Flow phantom description. Radiograph (left side) shows a linear tube section angled at a 20° incline from left to right. This linear section included a 40% stenosis (ie, a 5- to 3-mm diameter reduction plus subsequent expansion back to 5 mm) over a 3-cm tube length. There is also a curved tubing section that forms two loops. These are intended to be anatomically curved and possess diameter fluctuations with a mean of 5 mm. Schematic (right side) shows the position of stenotic tubing section. Stenotic section and transition zone are not to scale.

Multisite Multisystem Study

This Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance study (March 2017 to March 2019) consisted of volume flow measurements at three separate sites for each scanner (ie, radiology or engineering Departments with trained personnel with MD or PhD degrees; Fig 2). Eight experiments were conducted at each site. Experiment 1: Volume flow was measured from 1 to 12 mL/sec in steps of 1 mL/sec at a depth of 4 cm. The user was instructed to select the color flow gain such that the entire lumen would be filled with color pixels plus some background color pixels. The wall-filter cutoff was set to minimum. Experiment 2: Depth dependence was determined between 2.5 and 7.5 cm in steps of 0.5 cm (curved path of lumen, flow 6 mL/sec). Experiment 3: Color flow gain was stepped through 12–14 values (depending on the system), from no color pixels to full blooming (depth, 4 cm; flow, 6 mL/sec). Experiment 4: Finally, the user was instructed to measure volume flow distal to a lumen stenosis (1 and 2 cm past the center of the stenosis, at approximately 4- and 3.75-cm depth, respectively). Three flows (1, 6, and 12 mL/sec) were measured at each poststenosis position. Experiments 5–8 were the same as 1–4, except that constant (ie, nontime varying) flow (experiments 1–4) was switched to pulsatile flow (time varying at 60 beats per minute, experiments 5–8). A total of 738 data sets were recorded, consisting of 18 450 image volumes. Data processing was performed by O.D.K. using custom scripts (Matlab, R2018b; Mathworks, Natick, Mass) to read scanner data. Flow was computed for all three scanners by using the same algorithm (18).

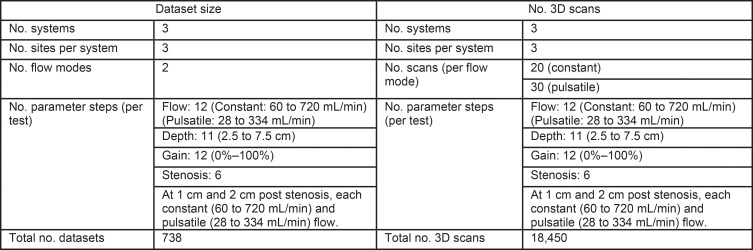

Figure 2:

Structure of the multisite multisystem study, with three systems at three different sites per system. The study at each site included four tests (flow, depth, gain, and stenosis) taken under constant and pulsatile flow. This resulted in a total of 738 datasets consisting of 18 450 image volumes. 3D = three-dimensional.

Statistical Analysis

Bias (mean percent difference from truth) and coefficient of variation were computed. A generalized linear model (SAS version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was fit to determine if bias differed as a function of site, system, and true value. The dependent variable in the model was the percent bias, and the independent variables in the model were the ground truth value, site, and system. The null hypothesis was that site, system, and the ground truth value do not affect the bias. A similar model was fit for experiments 1, 4, 5, and 8 to determine if the reproducibility, defined as the standard deviation of measurements among sites at the same truth value, divided by the truth value (ie, within-subject coefficient of variation), differs between systems. In this model, the dependent variable was the within-subject coefficient of variation and the independent variables were the ground truth value and system. The null hypothesis was that the ground truth value and system do not impact the reproducibility. A P value of .05 was used to assess significance of the independent variables.

Results

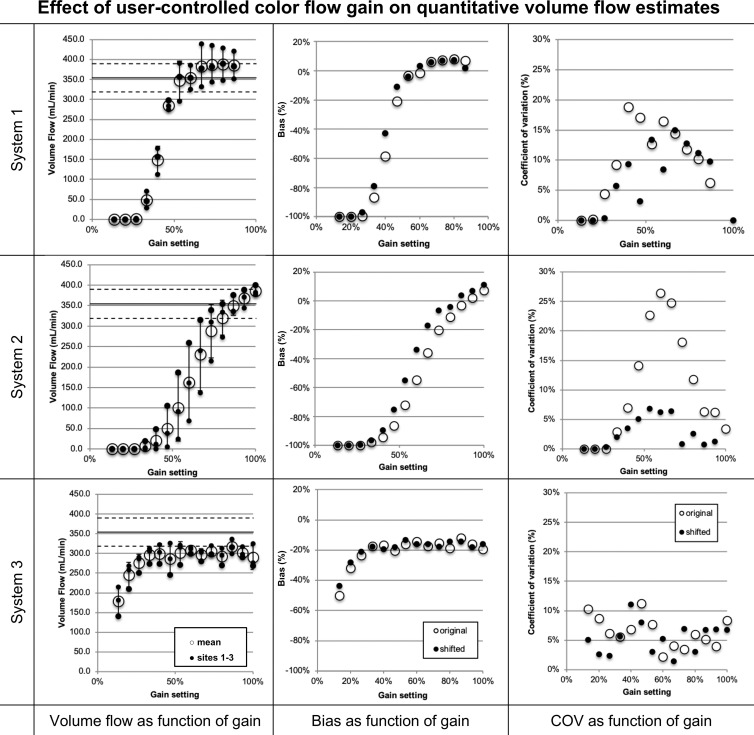

User-controlled Color Flow Gain Response of QBF Estimates

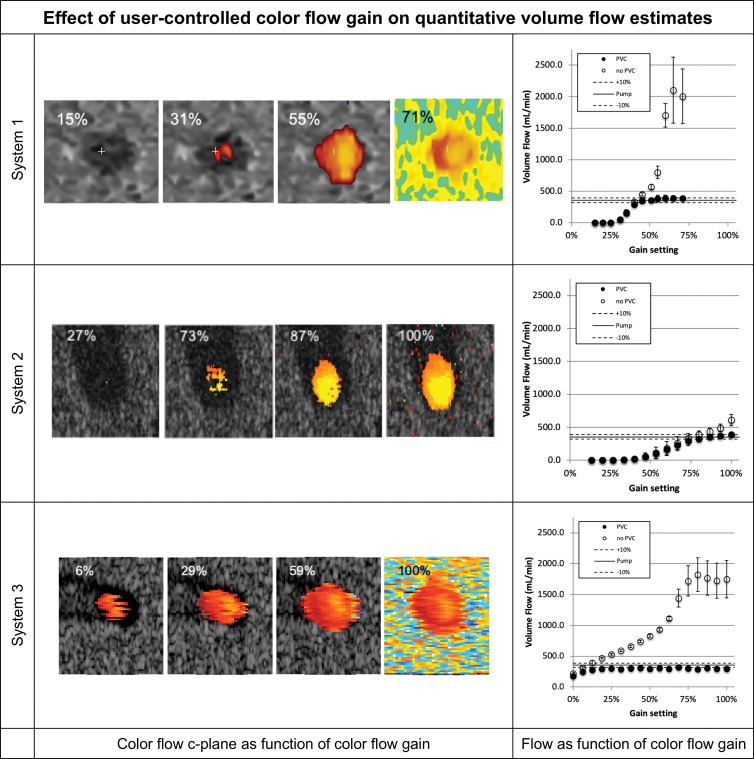

We investigated 3D QBF measurement dependence on color gain to decrease user and scanner variability during measurement. For this, we recorded the color flow gain response for each enrolled scanner. Figure 3 shows the c-plane response of each system along with the volumetric flow estimate resulting from the acquired data for each gain setting for a single testing site. The flow graphs present volume flow calculated with and without partial volume correction. As color flow gain increases, the lumen fills and may bloom, potentially affecting volume flow measurements.

Figure 3:

Volume flow as a function of color flow gain (at a single testing site). For each row the color flow c-plane and the computed volume flow are shown as a function of color flow gain. The c-plane is shown for four representative gain levels, whereas the computed volume flow is shown for 12–17 steps across the available gain settings. Flow was computed with (solid circles on the graphs) and without (hollow circles on the graphs) partial volume correction. Partial volume correction accounts for pixels that are only partially inside the lumen. Therefore, high gain (ie, blooming) does not result in overestimation of flow. Systems 1 and 2 converge to true flow after the lumen is filled with color pixel. System 3 is nearly constant regarding gain and underestimates the flow by approximately 17%. Shown are mean flow estimated from 20 volumes, and the error bars show standard deviation.

Figure 4 shows the functional dependence of volume flow regarding color flow gain for each of the three sites and their means. Biases and coefficients of variation are also shown in Figure 4. Average absolute biases for systems 1, 2, and 3 for constant and pulsatile flow after filling the lumen with color pixels were 6.3% and 18.5%, 8.5% and 9.0%, and 16.6% and 6.2%, respectively, with respective coefficients of variation of 10.8% and 4.3%, 7.3% and 6.7%, and 6.7% and 5.3%. Error bars represent the standard deviation as computed from three sites for each system. The large error of system 2 triggered us to investigate the effect of system sensitivity. The US probe and/or the US scanner may vary in its overall sensitivity to flow. For sites that use the same model scanner but different actual systems, the relative gain response may be shifted. We have therefore allowed the gain curves to shift toward smaller or larger gain values. Coefficient of variation between sites changes nonsignificantly (systems 1, P = .10 and 3, P = .34) between shifted and original data, except for system 2, which reduces from a maximum of 26% to 7% (P = .002).

Figure 4:

Volume flow as a function of color flow gain. Shown for each row are (left) volume flow (small ●) for systems 1, 2, and 3, respectively, and the mean flow (large ○) and (middle and right) mean bias and coefficient of variation of mean flow between sites (large ○), respectively. Possible differences in system sensitivity between systems 1, 2, and 3 were compensated by allowing a gain offset between sites. The results are shown (small ●). System 2 shows a decrease of coefficients of variation from a maximum of greater than 25% before compensation to 7% after compensation (P = .002). Systems 1 and 3 show no appreciable change. COV = coefficient of variation.

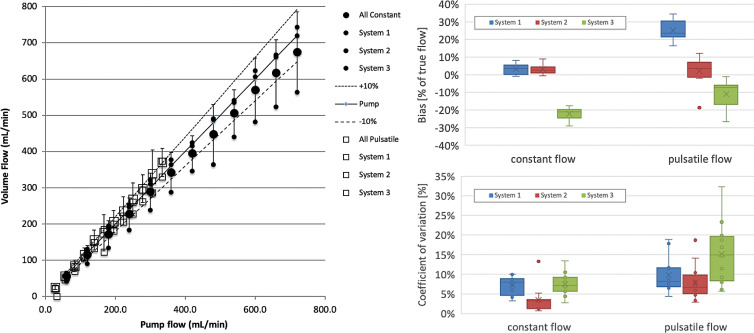

Flow Response of QBF Estimates

Physiologic flow can be observed over a large range. We therefore acquired data ranging from 1 to 12 mL/sec (60 to 720 mL/min, see Fig 5). Constant and pulsatile flow were recorded and are shown as means over three systems. Individual means of individual systems over three sites are shown in respective small symbols and labeled in the legend. Also shown are the true pump flow and ±10% demarcations. One system underestimated systematically for both constant and pulsatile flow. Another system overestimated for pulsatile flow conditions. Two systems tracked within ±10%. Biases and coefficients of variation, separated for constant and pulsatile flow, are shown in Figure 5. Systems 1, 2, and 3 are plotted and are detailed in the Figure 5 caption.

Figure 5:

Computed volume flow as a function of pump flow rate shows volume flow versus pump flow rate (left side), bias in percent of true flow (top right side), and coefficient of variation (lower right side). Data shown are from three systems (blue, red, green) averaged across three sites each at two conditions (constant flow and pulsatile flow). The identity of the systems is hidden by using uniform plot symbols. Constant flow (left) is plotted (●). Mean across systems 1, 2, and 3 is shown (large ●), which are also shown (small ●). Pulsatile flow is plotted (□). The mean (large □) across systems 1, 2, and 3 is shown, and their means are also shown (small □). Box and whisker plots of bias and coefficient of variation for all systems (right side) are shown and split into constant and pulsatile flow. Box plots are shown with error bars (standard deviation), mean (x), median (horizontal line in each box), and 25th–75th percentile range for each system and flow condition. The mean biases (top right) for systems 1, 2, and 3 are, respectively, 3.5%, 3.0%, and −22.1% for constant flow, and 24.9%, 2.1%, and –10.9% for pulsatile flow. Coefficients of variation (bottom right) as box plots for the same data are, respectively, 6.9%, 3.3%, and 9.6% for constant flow and 7.7%, 8.2%, and 17.3% for pulsatile flow.

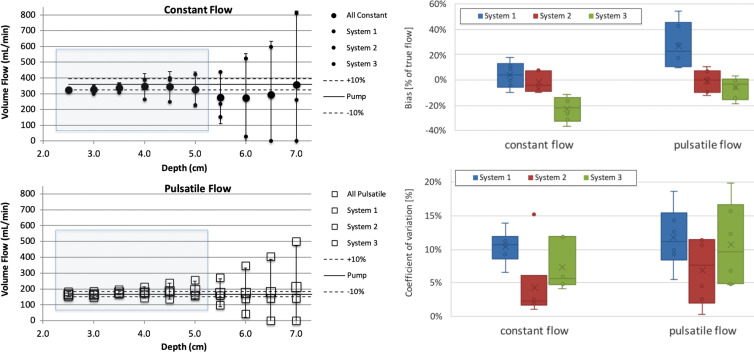

Depth Dependence of QBF Estimates

Data over the depth range of 2.5–7 cm is shown on Figure 6. Generally, the error bars increased with depth, and we decided to exclude data from 5.5 to 7 cm from the statistical analysis. Biases and coefficients of variation for data from 2.5 to 5 cm in depth, separated for constant and pulsatile flow, are shown on Figure 6. Systems 1, 2, and 3 are plotted as box plots and are detailed in Figure 6. Although system 3 had a comparatively tighter spread over depth, it showed a larger overall bias. Coefficients of variation were mostly between 10% and 15%, except for outliers, which may be subsequently removed because they are outside the operating range for a given imaging probe (eg, large depth for a high-frequency array).

Figure 6:

Computed volume flow as a function of c-plane (lateral elevational plane of equal distance from the transducer) depth. The left side shows volume flow versus c-plane depth for constant and pulsatile flow in top and bottom panel, respectively. The right side shows box and whisker plots that show bias for each system averaged across sites in percent of true flow within the blue shaded range in the left-side panel. Coefficient of variation is shown (lower right side) for the same blue shaded range of the left-side panel. Data shown are composed of three systems at two conditions, constant flow and pulsatile flow. Constant flow is plotted (upper left side; ●). The mean across systems 1, 2, and 3 is shown (large ●), and each system mean is shown (small ●). The identity of the systems is hidden by using uniform plot symbols. Pulsatile flow is plotted (lower left; □). The mean across systems 1, 2, and 3 is shown (large □), and each system mean is shown (small □). Box plots of bias (top right) and coefficient of variation (bottom right) for all systems are split into constant and pulsatile flow. Box plots are shown with error bars (standard deviation), mean (x), median (horizontal line), and 25th–75th percentile range for each system and flow condition. The mean biases for systems 1, 2, and 3 are, respectively, 3.7%, −2.0%, and −22.8% for constant flow and 27.2%, −0.9%, and −5.9% for pulsatile flow. The mean coefficients of variation are, respectively, 10.0%, 4.6%, and 10.1% for constant flow and 9.2%, 6.9%, and 11.6% for pulsatile flow.

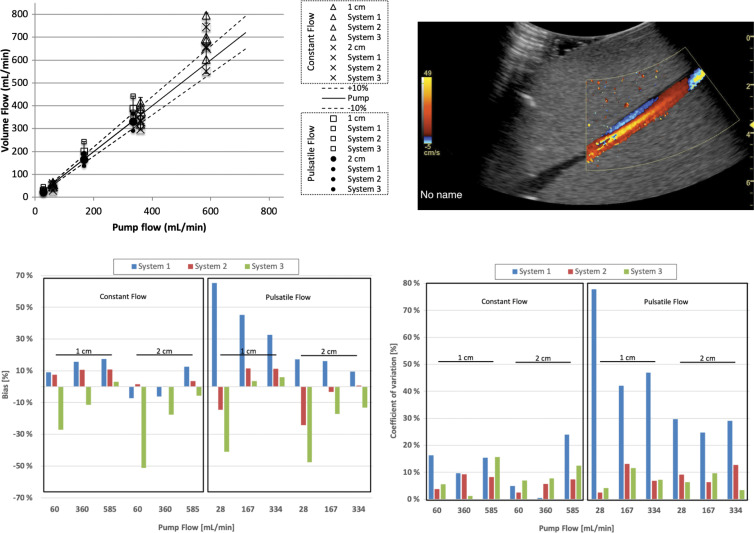

Poststenotic Response of QBF Estimates

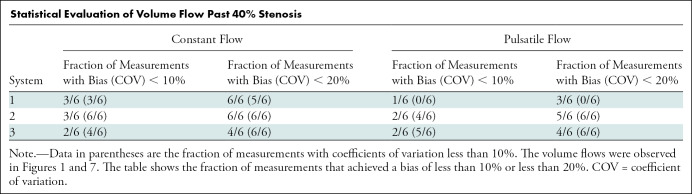

Stenosis may induce turbulence or other types of flow aberrations such as flow reversal (Fig 7, top right). We therefore measured flow at two distances, 1 and 2 cm, downstream of the stenosis in the phantom. Three flow rates were assessed (60, 360, and 585 mL/min for constant flow, and 28, 167, and 334 mL/min for pulsatile flow). Figure 7 shows that volume flow continued to scale with true flow, although there was a tendency to overestimate at higher flow rates. Table summarizes these results. Biases and coefficients of variation for these data are grouped into constant and pulsatile flow and subdivided into 1- and 2-cm distances from the stenosis. For each subgroup, three flow settings are plotted for each system. Systems are color coded in the same format as in Figures 5 and 6. Poststenotic constant and pulsatile flow biases for systems 1, 2, and 3 were 1.8% and 31.2%, 5.7% and −3.1%, and −18.3% and −18.2%, respectively.

Figure 7:

Volume flow computation of flow distal (downstream) to a 40% stenosis. Computed flow at c-planes (ie, the lateral elevational plane of equal distance from the transducer) located 1 and 2 cm past the stenosis at constant and pulsatile flow conditions. Top left graph shows computed volume flow as a function of pump flow. Constant flow is shown at 1 cm (∆) and 2 cm (×) distal (ie, downstream) to the stenosis and pulsatile flow at 1 cm (□) and 2 cm (●) distal (downstream) to the stenosis, respectively. For constant flow, bias and coefficient of variation are almost all less than 20%. Figure 2 shows analysis of these results. Example screenshot (top right) is shown for poststenotic flow. Bias at 1 and 2 cm poststenosis (bottom left) is shown and averaged between three sites. Coefficient of variation at 1 and 2 cm poststenosis (bottom right) is shown and averaged between three sites.

Statistical Evaluation of Volume Flow Past 40% Stenosis

Discussion

The objective of our study was to test a method for measuring quantitative blood flow by using three-dimensional US. Specific relevant physiologic and patient factor challenges were investigated (ie, blood flow rates and changes in measurement depth, user factors such as color flow receive gain, and alterations in flow past a stenosis).

The reader should not be surprised by the negative bias of low gain settings because the user would not assess a blood vessel that is not filled with color pixels. Partial volume correction demonstrates the convergence of measured flow to true flow as gain was increased beyond the point where the blood vessel is filled with color pixels. Further, our method of measuring QBF has no inherent dependence on the absolute flow rate. Given the range of tested flows, our method may be suitable for a range of applications including peripheral vascular flow and cerebral blood flow estimation but excluding perfusion and cardiac output. Estimating flow across a range of depths was expected to show the limits of the technique by using the present imaging probes and lumen diameter. Having an insufficient number of color flow beams within the lumen diameter for good reference power values for partial volume correction (Appendix E1 [online]) and diminishing Doppler sensitivity may have contributed to increasing coefficient of variation at larger depth, where diverging beams and attenuation become substantial.

Flow past a stenosis may introduce turbulence or other flow disturbances. Note that our method yields volume flow not velocities. Volume flow is the same proximal, at, and distal to the narrowing. Velocities change but flow is conserved. Therefore, there is no a priori reason to measure volume flow at or beyond a stenosis except for acoustic access. If volume flow is the goal of a measurement, it would make sense to make the measurement where the flow is most stable to decrease measurement variation introduced by turbulence.

There are no physical or technologic barriers to the implementation of our method on a clinical US scanner because only postprocessing software is required without hardware changes. The only instruction for the user to obtain accurate measurements is to place the color flow region-of-interest measurement on only one blood vessel, and not to measure multiple blood vessels at one time. Volume flow computation is rapid, approximately 1 second if implemented within the scanner software, and could be shown as mean (or mean ± standard error); this is much quicker than the current blood flow calculation with angle-corrected pulsed-wave Doppler.

Blood flow estimation has a multitude of clinical applications, including more accurate blood flow measurement in hemodialysis arteriovenous fistulas and grafts, evaluating stenosis and function in transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (22), and other vascular systems where blood flow quantification may be important to assess disease and response to treatment. Umbilical cord blood flow is a promising area that could potentially be used to assess intrauterine growth retardation and pre-eclampsia (20). In a cohort study enriched with pre-eclampsia or risk of pre-eclampsia, a significant negative correlation between volume flow and pre-eclampsia was found (P = .04) (24).

Our study had limitations. Currently, the tested method can only be applied to lumens with at least four color flow beams across the lateral and elevational lumen cross section. Also, only lumens completely encompassed in the lateral elevational plane can be assessed. In addition, this method only works on 3D color flow data. Adequate selection of the pulse-repetition frequency and color flow gain should not be seen as a limitation because it is evident that poor pulse-repetition frequency selection and lack of color flow power will result in inadequate flow computation. Both of these parameters could ultimately be set automatically by the US scanner and further reduce operator dependence. In addition, our study should be seen as preliminary work, which requires further investigations to address results that showed large bias or large coefficient of variation and to define acceptable flow estimation limits for bias and coefficient of variation for specific clinical applications because these results are only in a phantom.

The reduction of assumptions (no out-of-plane Doppler angle, symmetric out-of-plane flow profile) and the reduction of user input (no Doppler angle correction, no lumen diameter measurement) showed that three-dimensional US measurement of volumetric blood flow has the potential to be quantitively accurate, which has a variety of possible applications throughout the human body. Overall bias and variation resulting from our multisite multisystem study are promising. If scanners across manufacturers have a uniform distribution of bias, then minimizing variation is paramount for patient assessment and monitoring response to therapy. However, ultimately the true correct absolute flow must be obtained with minimal bias and variation. This will also allow for the derivation of associated measures such as oxidative metabolism.

APPENDIX

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Philips Healthcare, GE Healthcare, Siemens Healthcare, Hitachi Healthcare and Canon Medical Systems USA for supplying the US scanners and/or insightful discussions. We thank RSNA and AIUM for administrative support and Sun Nuclear (Middleton, Wis) for manufacturing and supplying the flow phantom. We thank Kathi Minton for arranging conference calls and administrative support.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (HHSN268201000050C, HHSN268201300071C, and HHSN268201500021C), Radiological Society of North America, and American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine.

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: O.D.K. Activities related to the present article: disclosed money to author’s institution for support for QIBA meetings from the RSNA; disclosed equipment support from GE, Philips, Sun Nuclear, and Toshiba (Canon); disclosed administrative support from American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM). Activities not related to the present article: disclosed board membership on the Board of Governors AIUM. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. S.Z.P. disclosed no relevant relationships. C.B. disclosed no relevant relationships. M.F.B. disclosed no relevant relationships. P.L.C. Activities related to the present article: disclosed money to author for support for travel from QIBA of RSNA. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed travel support from the AIUM. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. S.C. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed money paid to author for consultancy from Sonoscape; disclosed money paid to author’s institution for patents and royalties. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. T.N.E. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed employment from Canon Medical Systems. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. J.G. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed money paid to author’s institution for grant supported by Canon Medical Systems; disclosed money paid to author for travel to RSNA meeting from Canon. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. M.E.L. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed money paid to author for royalties from Elsevier, Oxford; disclosed that author receives a salary for deputy editor position from Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. A.M. disclosed no relevant relationships. N.O. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed money to author’s institution for statistical consulting services for QIBA projects from the RSNA. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. M.L.R. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed grants/grants pending from Philips Ultrasound; disclosed payment for lectures from Philips Ultrasound; disclosed travel and accommodations expenses paid by Philips Ultrasound. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. J.M.R. Activities related to the present article: disclosed a grant from Philips Ultrasound. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. J.A.Z. disclosed no relevant relationships. J.B.F. Activities related to the present article: disclosed money to author’s institution for support for QIBA meetings from the RSNA; disclosed equipment support from GE, Philips, Canon, and Sun Nuclear; disclosed administrative support from AIUM. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed board membership with AIUM; disclosed grants/grants pending from Philips Healthcare. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships.

Abbreviations:

- QBF

- quantitative blood flow

- 3D

- three-dimensional

References

- 1.Shung KK. Diagnostic ultrasound: imaging and blood flow measurements. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oglat AA, Matjafri MZ, Suardi N, Oqlat MA, Abdelrahman MA, Oqlat AA. A review of medical Doppler ultrasonography of blood flow in general and especially in common carotid artery. J Med Ultrasound 2018;26(1):3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill RW, Kossoff G, Warren PS, Garrett WJ. Umbilical venous flow in normal and complicated pregnancy. Ultrasound Med Biol 1984;10(3):349–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill RW. Measurement of blood flow by ultrasound: accuracy and sources of error. Ultrasound Med Biol 1985;11(4):625–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holland CK, Clancy MJ, Taylor KJ, Alderman JL, Purushothaman K, McCauley TR. Volumetric flow estimation in vivo and in vitro using pulsed-Doppler ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol 1996;22(5):591–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Theodoraki K, Theodorakis I, Chatzimichael K, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of abdominal organs after cardiac surgery. J Surg Res 2015;194(2):351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper KM, Bernstein IM, Skelly JM, Heil SH, Higgins ST. The Independent Contribution of Uterine Blood Flow to Birth Weight and Body Composition in Smoking Mothers. Am J Perinatol 2018;35(5):521–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chien A, Wang YL, McWilliams J, Lee E, Kee S. Venographic Analysis of Portal Flow After TIPS Predicts Future Shunt Revision. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2018;211(3):684–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma IWY, Caplin JD, Azad A, et al. Correlation of carotid blood flow and corrected carotid flow time with invasive cardiac output measurements. Crit Ultrasound J 2017;9(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NKF-DOQI clinical practice guidelines for vascular access. National Kidney Foundation-Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative. Am J Kidney Dis 1997;30(4 Suppl 3):S150–S191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vascular Access 2006 Work Group . Clinical practice guidelines for vascular access. Am J Kidney Dis 2006;48(Suppl 1):S176–S247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robbin ML, Greene T, Allon M, et al. Prediction of arteriovenous fistula clinical maturation from postoperative ultrasound measurements: findings from the hemodialysis fistula maturation study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018;29(11):2735–2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robbin ML, Greene T, Cheung AK, et al. Arteriovenous fistula development in the first 6 weeks after creation. Radiology 2016;279(2):620–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moser U, Vieli A, Schumacher P, Pinter P, Basler S, Anliker M. A Doppler ultrasound device for determining blood volume flow [in German]. Ultraschall Med 1992;13(2):77–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun Y, Ask P, Janerot-Sjöberg B, Eidenvall L, Loyd D, Wranne B. Estimation of volume flow rate by surface integration of velocity vectors from color Doppler images. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1995;8(6):904–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poulsen JK, Kim WY. Measurement of volumetric flow with no angle correction using multiplanar pulsed Doppler ultrasound. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 1996;43(6):589–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lui G, Burns P. The attenuation compensated c-mode flowmeter: a new Doppler method for blood volume flow measurement. In: 1997 IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium Proceedings. An International Symposium (Cat. No. 97CH36118), Toronto, Canada, October 5–8, 1997. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kripfgans OD, Rubin JM, Hall AL, Gordon MB, Fowlkes JB. Measurement of volumetric flow. J Ultrasound Med 2006;25(10):1305–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richards MS, Kripfgans OD, Rubin JM, Hall AL, Fowlkes JB. Mean volume flow estimation in pulsatile flow conditions. Ultrasound Med Biol 2009;35(11):1880–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinter SZ, Rubin JM, Kripfgans OD, et al. Three-dimensional sonographic measurement of blood volume flow in the umbilical cord. J Ultrasound Med 2012;31(12):1927–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura S, Streiff C, Zhu M, et al. Evaluation of a new 3-dimensional color Doppler flow method to quantify flow across the mitral valve and in the left ventricular outflow tract: an in vitro study. J Ultrasound Med 2014;33(2):265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinter SZ, Rubin JM, Kripfgans OD, et al. Volumetric blood flow in transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt revision using 3-dimensional Doppler sonography. J Ultrasound Med 2015;34(2):257–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudson JM, Williams R, Milot L, Wei Q, Jago J, Burns PN. In vivo validation of volume flow measurements of pulsatile flow using a clinical ultrasound system and matrix array transducer. Ultrasound Med Biol 2017;43(3):579–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinter SZ, Kripfgans OD, Treadwell MC, Kneitel AW, Fowlkes JB, Rubin JM. Evaluation of umbilical vein blood volume flow in preeclampsia by angle-independent 3D sonography. J Ultrasound Med 2018;37(7):1633–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.