Abstract

Objectives: In older persons with heart failure (HF), an inability to self-manage their disease condition can result in poor health outcomes and quality of life. With the rise in smartphone use and digital game playing among older adults, digital tools such as sensor-controlled digital games (SCDGs) can offer accessible health-promoting tools that are enjoyable and easy to use. However, designing SCDGs that are compelling and aligned with their life values and self-management needs can be challenging. This article describes a qualitative study with older adults with HF who were recruited from a cardiac rehabilitation laboratory in central Texas to identify their perceptions and expectations regarding a SCDG for HF self-management.

Materials and Methods: A low-fidelity prototype that demonstrated the features of a SCDG was used to obtain the participants' perceptions about the value of SCDGs for HF self-management with respect to content, customization, flexibility, and usability through qualitative interviews.

Results: We interviewed 15 patients with HF (53% women; age range, 53–90 years; 60% white). The concept of SCDGs for HF self-management was highly acceptable (80%). Participants provided suggestions for game characters, progress in the game, and game notifications and incentives. Perceived benefits included helping users track their behaviors and establish routines, become informed on strategies to manage HF, and empower themselves to take charge of their health.

Conclusions: The study's findings will guide personalization of SCDG development to motivate patient engagement in HF self-management behaviors.

Keywords: Heart failure, Self-management, e-Health, Digital games, Connected sensors

Background and Significance

Heart failure (HF) is a global pandemic, since it affects ∼26 million people worldwide.1 In older persons, an inability to self-manage HF results in frequent hospitalizations and poor quality of life.2–5 To facilitate engagement in HF self-management behaviors, digital games can be designed to deliver health education or promote healthy behaviors by enabling participants to set goals, and measure changes in health behaviors while still enjoying playing a game.6 Digital game playing among older adults is growing fast; in 2015, 40% of U.S. digital game players were of age ≥50.7 In a recent scoping review of studies on the use of digital games for patients with cardiovascular diseases, 88% of the reviewed studies sampled participants ≥50 years of age; across all of the studies, digital games significantly improved physical activity and were enjoyed by 79%–93% of participants.8 Moreover, digital game playing has been associated with positive effects on physical health outcomes, cognitive effects, and behaviors in older adults without any associated adverse effects, although these findings still require validation from studies of higher quality.9,10

Increased robustness and reliability of telecommunication network connectivity have eased the integration of real-time behavior data from behavior-tracking physical devices and sensors (e.g., activity trackers, weight scales) into applications that are loaded on mobile devices (e.g., game apps). In a sensor-controlled digital game (SCDG), sensor data on behaviors are synchronized with a mobile gaming application to provide immediate feedback on real-time behaviors by triggering game progress, rewards, and incentives based on participants' real-time behaviors.11 Moreover, game-playing data can provide opportunities for extended monitoring and analysis of behaviors as well as insights on optimal interactions with clinicians and/or peers, all of which allow individuals to obtain relevant assistance when needed.12

Nevertheless, designing SCDGs that are both compelling, easy to use and includes game components desired by older adults such as achievement, realism, educational content, cognitive exercises, or incorporation of their hobbies such as travel13–15 is challenging.16 The SCDG design with respect to content, customization, and usability must align with the life values and self-management needs of older adults with HF.14,15 This article reports perceptions and expectations of older adults diagnosed with HF regarding SCDGs for HF self-management.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas at Austin approved this descriptive, qualitative study. During summer 2018, English-speaking HF participants 50+ years, not legally blind and alert and oriented on the cognitive functioning item on the Outcome and Assessment Information Set,17 were recruited at a cardiac rehabilitation laboratory in central Texas. All participants were provided $20 gift card in appreciation for their participation in the study.

Data collection

Participants completed a demographic survey on health conditions, hospitalizations in the past year, and current digital game playing. The first author used a semistructured qualitative interview guide to interview participants for 30–45 minutes at either the clinic or the participant's home. The Rev transcription application (https://www.rev.com) was used for recording and transcribing interviews. The interviews solicited information on the impact of HF on quality of life and desired goals for HF self-management. A low-fidelity prototype of the SCDG was developed for the interview using images that presented potential features of a HF digital game, images from a prior HF game,18 and commercially available sensor devices. A simulation game genre to simulate empathy with a game avatar, which progresses on a mountain and experiences health status changes based on participants' real-time behaviors that are tracked by sensors, was used in the prototype. The images were presented in a PowerPoint slideshow on a laptop to obtain participants' perceptions on game-related goals, characters, genre, incentives, visualization of game progress, alerts, notifications, content, and the value of the SCDG for HF self-management and related health outcomes (Figs. 1–3).

FIG. 1.

SCDG prototype avatar no. 1 image. SCDG, sensor-controlled digital game.

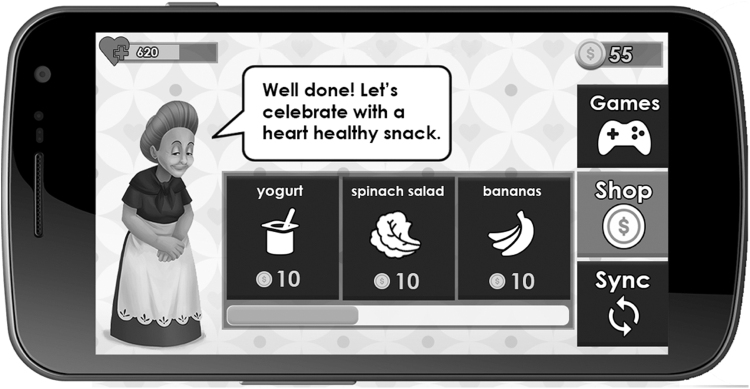

FIG. 3.

Incentive of healthy food for game avatar.

Data analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis. Two of the authors (K.R. and C.A.F.) used Microsoft Word and Excel to code and organize the interview data into categories that reflected emergent themes. Coding reports were summarized and crosschecked to ensure consistency of interpretation. Whenever the two reviewers disagreed on the codes or categories, transcripts were reviewed again and discussed until consensus was achieved on themes. Recruitment of participants continued until data saturation was reached when no new codes arose through iterative and open-ended questioning.

Results

Of the 24 potential participants approached for the study, 15 (63%) consented to participate (see Table 1 for demographic characteristics). Reasons for refusal included travel plans, transportation issues, surgery, or lack of interest. The themes derived from the interviews are summarized in Table 2 and explained as follows.

Table 1.

Participants' Characteristics

| Demographics (N = 15) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| 50–59 | 3 (20) |

| 60–69 | 6 (40) |

| 70–79 | 5 (33) |

| 80–89 | 0 (0) |

| >90 | 1 (7) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 7 (47) |

| Female | 8 (53) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (13) |

| Asian | 1 (7) |

| African American | 3 (20) |

| White | 9 (60) |

| Highest education level | |

| High school graduate, diploma, or the equivalent (e.g., GED) | 4 (27) |

| Some college credit, no degree | 4 (27) |

| Trade/technical/vocational training | 1 (7) |

| Bachelor's degree | 2 (13) |

| Graduate degree | 4 (27) |

| Living situation | |

| I live alone | 3 (20) |

| I live with a family member | 9 (60) |

| I live with another adult | 3 (20) |

| I live in a | |

| Single family home | 9 (60) |

| Apartment | 6 (40) |

| How many times have you been hospitalized for HF-related reasons in the past 12 months? | |

| 0 | 1 (7) |

| 1–2 | 9 (60) |

| 3–4 | 5 (33) |

| How many times have you visited clinicians in an outpatient setting for HF? | |

| 0 | 1 (7) |

| 1–2 | 6 (40) |

| 3–4 | 3 (20) |

| >4 | 5 (33) |

| What other health conditions have you been diagnosed with? | |

| Hypertension | 7 (47) |

| Arthritis | 4 (27) |

| Diabetes | 2 (13) |

| Other cardiac conditions | 2 (13) |

| Neurological conditions | 6 (40) |

| Mental health conditions | 2 (13) |

| Respiratory conditions | 1 (7) |

| Autoimmune disorders | 1 (7) |

| How long have you been diagnosed with HF? | |

| Less than a year | 9 (64) |

| 1–4 years | 0 (0) |

| 5–10 years | 3 (21) |

| 10–15 years | 0 (0) |

| >15 years | 2 (14) |

| Have you played digital games before? | |

| Yes | 8 (57) |

| No | 6 (40) |

| If yes, what games have you played? | |

| Razzle, Dragon boat, Pac Man, Dino | |

| Baseball, football | |

| Poker, slots, solitaire | |

| Matching (color blocks), Candy Crush | |

| Word games | |

| If yes, what kind of digital games do you like to play? | |

| Card games | 2 (14) |

| Word games | 1 (7) |

| Puzzle | 1 (7) |

| Casino games | 3 (20) |

| Other (please specify) | 3 (20) |

GED, general education development; HF, heart failure.

Table 2.

Themes Derived from Interviews

| HF effect on life aspects of most value, desired behavior goals |

| Perception of sensor-controlled digital game |

| Preferences for SCDG features |

| Perceived impact of SCDGs on HF behaviors and health outcomes |

SCDG, sensor-controlled digital game.

HF effect on life aspects of most value, desired behavior goals

Participants highly valued a stable health status that would enable them to spend quality time with their family, ability to engage in hobbies, financial stability, happiness, and faith in God. However, HF was perceived to adversely impact participants' physical ability, participation in daily activities, socializing and hobbies, financial stability and happiness. One participant, participant no. 5 (71 years, South Asian, male) reported the following limitations with a diagnosis of HF: “I haven't been able to travel. Had to cancel planned trips. Reduced social events attended, missed two significant weddings. I am unable to drive.”

HF self-management behavior goals targeted for change by the participants included modifying salt intake and diet, increasing physical activity, daily monitoring of weight and other vital signs, taking medicine on time, restricting fluid intake, and stopping smoking and alcohol intake. Four participants wanted to resume activities in which they were able to engage before they were diagnosed with HF. According to participant no. 13 (65 years, Caucasian, female), “My long-term goals are just to try to keep up with it. I've lost some weight; try to lose some more weight. Try to get back to where I'm as active as I was before; which I'm almost there, but I'm not quite.” Lifestyle-related goals were voiced by participant no. 14 (69 years, African American, female), who reported, “I want to go back to work. I want to go back to doing things with my grand babies. I want to stop feeling tired. I want my chest to stop hurting, and I just want to heal.”

Perception of SCDG

Majority of the participants were receptive to the idea of using an SCDG. However, these older adults emphasized that such a game should be simple, and that the syncing of data between the sensors and the game app should be automatic, with little effort on the player's part. Some participants were concerned about the compatibility of the SCDG with their existing tracking devices, such as a Fitbit tracker or the Apple Watch. According to participant no. 10 (70 years, Caucasian, female), “If I have to get a different watch or change watches or pick up a different piece of equipment, I think I'd be much less inclined to do it.”

According to participant no. 6 (69 years, Hispanic, male), the activity tracker sensors would be valuable only if they could capture diverse physical activities that he engaged in, such as swimming or weightlifting in addition to walking or running. Setting daily goals for physical activity and tracking the progress of those goals within the game were perceived by some of the participants as a valuable motivational feature for engaging in that behavior. Participants indicated that finding ways to integrate game play into their current routines would support their playing the HF game; however, falling sick, getting discouraged during game play, busy schedules, the game being too demanding, or the game being boring would negate their playing the game. According to participant no. 7 (55 years, Caucasian, male), “Calling the SCDG a heart failure game trivialized it,” and participant no. 10 (70 years, Caucasian, female) did not like the use of the word “failure” in a digital tool to improve heart health, “If the powers that be refuse to take the heart failure word out of it, I wouldn't probably play.”

Preferences for SCDG features

Game character and genre

Majority of the participants preferred the use of human-like avatars to elicit empathy with the character in the game, although few did not care about game characters. Human game characters that matched the older age of the participants, appeared cheerful and active, and dressed in contemporary clothing were preferred by the participants. For example, perceptions of participant no. 10 (70 years, Caucasian, female) when shown Figure 1 were, “That looks like a before picture would be my problem with her. Her posture's terrible. She looks old and tired. Her legs…No, she's terrible.” But this participant was more approving of Figure 2, which showed an active, older adult person: “I think pictures that we can relate to can be extremely healing. So yes, an older fit person, because you pick up these current magazines and everybody's 30 years old.” However, some participants wanted fun animals to be offered as game characters, such as the Pink Panther, cats, or dogs. Stimulating games (e.g., word or numbers games such as Sudoku) were preferred by nearly half of the participants, of whom majority had a higher educational degree; more casual puzzle game genres (e.g., casino slots or matching objects by color) were preferred by others, of whom few had a higher educational degree.

FIG. 2.

SCDG prototype avatar no. 2 image.

Game goal

Avoiding negative consequences such as hospitalization was preferred as a game objective by majority of the participants. Such a goal might motivate participants to maintain their behaviors, because these participants detested hospitalizations. They said that they would feel responsible for the game avatar and would engage in behaviors to avoid the avatar's hospitalization. According to participant no. 9 (65 years, Caucasian, female), “I think that's a good negative reminder. Especially if you had to go to the hospital for heart failure, you know what that unpleasant experience is. I think that could be a good motivator.”

Some participants, however, thought that the game's goal should reflect aspects of wellness, because hospitalization might be too limiting or depressing. One participant suggested that progression in the game could be displayed visually through gradual change in the avatar's health status, so that negative consequences could be unveiled gradually rather than abruptly by a hospitalization. According to participant no. 10 (70 years, Caucasian, female), “That [hospitalization] could be down on the list. Number one would be, I feel great. I have a full and satisfying life. having character hospitalized would less motivate me to play … my goal is not to stay out of the hospital. My goal is to have a wonderful, vibrant life.”

Game content

Providing information and tips on managing HF was found valuable by a majority of the participants, and almost all participants favored mini-quizzes to test their knowledge and provide subsequent answers. Participant no. 12 (74 years, Caucasian, male) reported that the SCDG would be more meaningful if it also addressed content on managing HF-related comorbidities. However, to some participants such as participant no. 7 (55 years, Caucasian, male), HF information was not valuable as “That would have no value to me. I have a good understanding of what I should eat and how to prepare food properly. I don't need that type of reeducation.”

Game rewards

The option to earn game rewards and incentives was preferred by nearly half of the participants. Preferences for game rewards included earning higher points, levels, or trophies; receiving recipes for low-salt food items; suggestions for local restaurants offering low-salt food items; or receiving real-life rewards such as Amazon gift cards, coupons to grocery stores, or gym membership fees. Some participants strongly desired competition or challenging game tasks to attain a feeling of achievement. According to participant no. 6 (69 years, Hispanic, male), “I'm always about the rewards. I've got trophies all over the place. I'm all about the rewards. Open up my computer, get in the game or whatever, and see hey, I've got an attaboy. Because everybody likes to be congratulated.” However, some reported that the game's real value lay in inculcating good healthy behaviors and that game incentives did not matter. Thus, participant no. 2 (69 years, Caucasian, female) remarked, “Well, I would do it anyway, I mean it's not because of points, but I would do it because I know this is a healthy program to participate in.” Participant no. 14 (69 years, African American, female) would like game incentives that appealed to her culturally, such as culturally relevant food suggestions.

Game alerts and notifications

Some participants preferred a dashboard to see progress in their behaviors, including the use of brightly colored stars in a calendar. Preferences for notifications included reminders for both medications, especially at nighttime, and exercising, as well as rating for completion of daily behavior goals including tips to improve the rating the next day. To enhance effectiveness, participants preferred receiving one to two alerts per day, with at least one alert during midday, so that there would be enough time to complete a task.

Social support

Since majority of the participants said that they would like their family members to become involved in the game or receive notifications related to the game, perhaps this could be provided as an option. Participants also reported that the games being recommended by health practitioners such as a cardiologist would enhance their belief that playing the game would be helpful. According to participant no. 1 (65 years, Caucasian, female), “I would like that for my husband. I really would. Because right now, I don't feel like he's fully engaged with the diagnosis. He's fully supportive though.”

Perceived impact of SCDGs on HF behaviors and health outcomes

Majority of the participants reported that SCDGs could impact their HF and quality of life by helping them become more aware of their behaviors, stay on track, establish routines, obtain education and information that would help alleviate anxiety, receive reminders for behaviors, and take charge of their health. According to participant no. 14 (69 years, African American, female), “Well, right now I think it would be pretty valuable because I'm trying to do all these things and, I don't know, maybe I'll slack after a while but I haven't yet. It would be good to keep me on task.”

Some participants were unsure about the impact of an SCDG on HF as they had not played the SCDG or were not interested in playing digital games at all. According to participant no. 15 (90 years, Caucasian, female), “But I'm not gonna do any special things—I mean at 90, you really don't have to do that kind of stuff.”

Discussion

This study demonstrates the feasibility of using low-fidelity prototype to obtain HF older adults' opinions on the value of SCDGs for HF self-management. Digital games and sensors combined in the SCDG were acceptable as a medium to enhance self-management knowledge and motivate self-management behaviors. A high proportion of smartphone ownership (87%) as well as some use of fitness trackers (25%) indicated that these older adults might be ready to receive digital interventions and may be able to incorporate them within their daily routines. However, this implication should be regarded cautiously, because only 42% of older adults in the United States19 claim to own smartphones. The higher literacy of the sample may limit generalizability of the study's findings to HF patients from underserved communities. Also, participants' responses did not differ by race or gender for any of the interview themes, possibly due to small sample size.

Many participants struggled with engaging in self-management due to lack of knowledge, fatigue, painful comorbid conditions such as arthritis or fear of unsafe activity levels as observed in other studies.20 Digital gaming tools can encourage safe level of behaviors, and provide tips and information on safely increasing healthy behaviors.8 The opportunity to receive tips to problem-solve challenges to those behaviors within the digital game environment may help build cognitive skills and self-efficacy to engage in behaviors and make informed decisions about self-management activities within the context of daily life routines.10

One of the major challenges of contemporary digital tools is the ability to sustain interest in the tools long enough to make a significant impact on the older adults' behaviors and health status. About half of respondents in a national survey who had downloaded a health app had stopped using them in a national survey study.21 App features that are tailored to address a user's behavior motives, promote self-regulation as well as be relatable were found to contribute to a longer duration of engagement with mobile apps.22 The ability of SCDGs to tailor behavior goals to a person's ability, tailor content, or incentives to diverse cultural or literacy preferences and earn game incentives through obstacles and feedback in the SCDG based on the participant's real-time progress in those behaviors could be attributes that sustain longer term usage of SCDG. Digital games such as SuperBetter have been shown to reduce depressive symptoms, motivate users in difficult life situations, and help them retain good habits.23

Like the participants in Marston's survey study on older adults' game preferences,13 participants in this study preferred game characters that were more realistic and reflective of their active selves. Participants' preference for the puzzle game genre, and desire for competition and challenging game tasks to attain a sense of achievement was consistent with findings from Marston's survey study13 as well. Gamification components of challenges, tasks, quizzes, badges, and leader boards24 in a SCDG can be tailored to the participants' knowledge and activity levels to motivate them to maintain the avatar's optimal health status.

Since majority of the participants were diagnosed with HF within the past year in this study, participants could benefit from content that reinforces suggestions on HF self-management behaviors. In addition, the SCDG could help harness the care and social network of people diagnosed with HF by communicating critical messages triggered by weight and activity trackers to clinicians and caregivers. The findings of this study have informed our design and development of an SCDG called “Heart Health Mountain,”25 which we are currently testing in a randomized controlled trial with HF older adults.

Conclusion

The concept of SCDGs for HF self-management was highly acceptable to older adults with HF. The study's findings can guide personalization of SCDG development to motivate engagement in healthy self-management behaviors in people diagnosed with HF.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support with article development was provided by the Cain Center for Nursing Research and the Center for Transdisciplinary Collaborative Research in Self-management Science (P30, NR015335) at The University of Texas at Austin School of Nursing.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

M.O., the owner of Good Life Games, Inc. company, which develops health games for hire, provided the prototype game images for this study. The other authors do not report any conflict of interest in conducting this study.

Funding Information

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Ed and Molly Smith Fellowship to conduct this study. Research reported here was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award no. R21NR018229 (PI Radhakrishnan).

References

- 1. Ponikowski P, Anker SD, AlHabib KF, et al. Heart Failure: preventing disease and death worldwide. ESC Heart Fail 2014; 1:4–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van der Wal MH, Jaarsma T. Adherence in heart failure in the elderly: Problem and possible solutions. Int J Cardiol 2008; 125:203–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Riegel B, Moser DK, Anker SD, et al. State of the science: Promoting self-care in persons with heart failure. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2009; 120:1141–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jonkman NH, Westland H, Groenwold RH, et al. Do self-management interventions work in patients with heart failure? An individual patient data meta-analysis. Circulation 2016; 133:1189–1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lainscak M, Blue L, Clark AL, et al. Self-care management of heart failure: Practical recommendations from the Patient Care Committee of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2011; 13:115–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marston HR, Hall AK Gamification: applications for health promotion and health information technology engagement. In: Novak D, Tulu B, Brendryen H, eds. Handbook of Research on Holistic Perspectives in Gamification for Clinical Practice. Hershey, PA: IGI Global; 2016:78–104

- 7. Duggan M. Gaming and Gamers Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. 2015. www.pewinternet.org/2015/12/15/gaming-and-gamers (accessed July5, 2016)

- 8. Radhakrishnan K, Baranowski T, Julien C, et al. Role of digital games in self-management of cardiovascular diseases: A scoping review. Games Health J 2019; 8:65–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bleakley CM, Charles D, Porter-Armstrong A, et al. Gaming for health: A systematic review of the physical and cognitive effects of interactive computer games in older adults. J Appl Gerontol 2015; 34:NP166–NP189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hall AK, Chavarria E, Maneeratana V, et al. Health benefits of digital videogames for older adults: A systematic review of the literature. Games Health J 2012; 1:402–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brox E, Fernandez-Luque L, Tøllefsen T. Healthy gaming—Video game design to promote health. Appl Clin Inform 2011; 2:128–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marston HR, Woodbury A, Gschwind YJ, et al. The design of a purpose-built exergame for fall prediction and prevention for older people. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 2015; 12:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marston HR. Older adults as 21st century game designers. Comput Games J 2012; 1:90–102 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hanson VL, Gibson L, Bobrowciz A, MacKay A. Engaging those who are disinterested: access for digitally excluded older adults. Paper presented at ACM CHI 2010 Workshop on Senior-Friendly Technologies: Interaction Design for the Elderly, Atlanta, GA, 2010

- 15. Marston HR. Design recommendations for digital game design within an ageing society. Educ Gerontol 2013; 39:103–118 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Whitelock LA, McLaughlin AC, Leidheiser W, et al. Know before you go: Feelings of flow for older players depends on game and player characteristics. In: Proceedings of the First ACM SIGCHI Annual Symposium on Computer Human Interaction in Play. New York: ACM; 2014:277–286

- 17. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Home Health Quality Reporting Program. 2018. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HomeHealthQualityInits/index.html (accessed February21, 2018)

- 18. Radhakrishnan K, Toprac P, O'Hair M, et al. Interactive digital e-health game for heart failure self-management: A feasibility study. Games Health J 2016; 5:366–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Anderson M, Perrin A. Tech Adoption Climbs Among Older Adults Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. 2017. www.pewinternet.org/2017/05/17/tech-adoption-climbs-among-older-adults (accessed October30, 2018)

- 20. Siabani S, Leeder SR, Davidson PM. Barriers and facilitators to self-care in chronic heart failure: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Springerplus 2013; 2:320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krebs P, Duncan DT. Health app use among US mobile phone owners: A national survey. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015; 3:e101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baretta D, Perski O, Steca P. Exploring users' experiences of the uptake and adoption of physical activity apps: Longitudinal qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019; 7:e11636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roepke AM, Jaffee SR, Riffle OM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of SuperBetter, a smartphone-based/internet-based self-help tool to reduce depressive symptoms. Games Health J 2015; 4:235–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miller AS, Cafazzo JA, Seto E. A game plan: Gamification design principles in mHealth applications for chronic disease management. Health Informatics J 2016; 22:184–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Radhakrishnan K, Julien C, O'Hair M, et al. (2019). Usability assessment of a sensor-controlled digital game for older adults with heart failure. In: Gerontological Society of America Annual Conference, Austin, TX