Highlights

-

•

Human and economic capital increase organisational resilience.

-

•

Corporate social responsibility practices increase organisational resilience.

-

•

Organisational resilience affects the scope of adoption of anti-COVID-19 measures.

-

•

Organisational resilience increases perceived job security.

-

•

Perceived job security affects positively organisational commitment.

Keywords: COVID-19, Organisational resilience, Corporate social responsibility (CSR), Perceived job security, Organisational commitment, Hotels, Spain

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic will reduce the attractiveness of hospitality occupations. This particularly concerns senior management positions whose holders may substitute hospitality jobs with more secure and rewarding employment in other economic sectors. Organisational resilience of hospitality businesses, including their response to COVID-19, and corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices may, however, affect perceived job security of senior managers and, thus, influence their commitment to remain in their host organisations. This paper quantitatively tests the inter-linkages between the above variables on a sample of senior managers in hotels in Spain. It finds that the levels of organisational resilience and the extent of CSR practices reinforce perceived job security of managers which, in turn, determines their organisational commitment. Organisational response to COVID-19 affects perceived job security and enhances managers’ organisational commitment. To retain senior management teams in light of future disastrous events, hotels should, therefore, strengthen their organisational resilience and invest in CSR.

1. Introduction and theoretical background

The COVID-19 pandemic has imposed a number of significant detrimental, immediate and long(er) term, impacts on the international hotel sector (Jiang and Wen, 2020). The immediate impacts have by now become well apparent and reflected in the interrupted cash flows prompted by sudden business closures following governmental lockdown orders (Hall et al., 2020). Albeit temporary, such closures have endangered the business longevity of many hotels by slashing their revenues and disintegrating the long-established supply chains (Nicola et al., 2020). The long(er) term impacts of COVID-19 are yet implicit but likely to be exemplified by the diminished consumer demand for hospitality services in the foreseeable future due to health and hygiene precautions (Dube et al., 2020). Coupled with the need to decrease operational capacity in order to follow the newly-established social distancing rules (Hancock, 2020), this will reduce the long-term profitability of hotels, thus undermining the viability of their traditional business models (Gössling et al., 2020). There are speculations that the hotel sector will shrink significantly in the result of the pandemic, thus outlining bleak prospects for its current and future investors and employees (Taylor, 2020).

One of the main negative, long(er) term implications of COVID-19 for the hotel business is likely to be in the reduced attractiveness of hospitality occupations (Baum and Hai, 2020). Irregular and/or seasonal working patterns (Lee and Way, 2010) in the presence of zero-hours contracts (Filimonau and Corradini, 2019) coupled with a relatively low pay (Wan et al., 2014) have already discouraged many prospective employees from up-taking hotel jobs in the past. This has positioned staff recruitment and retention as a major challenge for hotel management in a pre-pandemic world (McGinley et al., 2017). COVID-19 will exacerbate this challenge as the uncertain future of the hotel business may prompt qualified workforce to seek employment in other economic sectors (Mao et al., 2020). The need for many hotels to put their employees on a furlough scheme (in the case of many developed countries) and/or make them redundant (in the case of many developing economies) in the time of the pandemic, may have presented hotel jobs as being highly insecure whilst positioning employment within the hotel sector as being fragile to external disruptions (Sogno, 2020). This perceived insecurity and fragility may negatively affect future recruitment of hotel staff (Mao et al., 2020).

Top managerial positions in hotels have been difficult to fulfil long before the pandemic (Birdir, 2002). This is attributed to the lack of appropriate expertise and experience (Cheung et al., 2010), but also assigned to the unwillingness of senior executives to work in the sector which offers limited scope for creativity and provides limited training (Wong and Pang, 2003) but, concurrently, requires significant levels of personal commitment, interpersonal communication, teamwork and stress resistance (Kichuk et al., 2019). Recruitment of senior hotel managers is likely to become even more problematic in a post-COVID-19 world. This is due to reduced attractiveness of hospitality employment in general, as discussed earlier, but also because of the potentially increased market demand for the most experienced and qualified (hotel) management staff occurring in other sectors of economic activity (Carnevale and Hatak, 2020). Increasing organisational commitment of senior hotel managers is, therefore, likely to represent a critical task for hotel owners/shareholders post pandemic.

It is argued that the (current) measures adopted by hotels to reduce the immediate detrimental effect of COVID-19 and any (future) measures (to be) put in place to minimise its long(er)-term impacts may influence organisational commitment of senior hotel managers. Although many hotels ceased to operate with an immediate effect following governmental orders to lockdown, some businesses undertook a number of steps in order to maintain (at least limited) operational activity and/or ensure a (more) rapid recovery. For example, some hotels were converted into temporary emergency hospitals (Catalan News, 2020); some provided their staff with restricted and/or ad-hoc employment opportunities, such as cooking food for take-away and deliveries (Healing Manor Hotel, 2020); and some offered so-called ‘holiday vouchers’ (often with a bonus payment) to existing customers to encourage their return after the lockdown orders are lifted, thus supporting operations post pandemic (Krinis, 2020). As for any (future) measures (to be) applied by hotels after the lockdown, whilst some are compulsory such as, for example, social distancing and public hygiene protocols (TUI Group, 2020), some can be voluntary such as, for instance, increased use of digital technology to reduce human contact and/or routine guest temperature checks in hotel lobbies (Pflum, 2020). The extent of application of the latter measures will be primarily dependent on the ‘good will’ of hotel owners and/or investors whose decisions on whether or not to implement these measures is likely to be underpinned by the availability of appropriate resources. It is argued that all these measures, cumulatively coined as an organisational response to the pandemic, may positively affect perceived job security of senior hotel managers, thus influencing their commitment to remain in current employment after COVID-19 is over.

The (current and future) measures adopted by hotels against the pandemic may have been determined by the levels of their organisational resilience. In simple terms, organisational resilience explains business preparedness to crises and disasters which provides scope for adequate predictive and adaptive algorithms/mechanisms to be put in place for prompt recovery (Filimonau and De Coteau, 2020; Lee et al., 2013; Nguyen et al., 2017). Although COVID-19 does not resemble any other past disaster or crisis, thus offering limited room for hotel managers to predict its impacts and design effective defensive frameworks (Sigala, 2020), it is argued that past disasters should have at least taught hotel businesses about the need to stay alert and allocate resources for any future disruptions. This can be referred to as the adaptive capacity element of organisational resilience (Orchiston, 2013). Further, past experience of crises and disasters should have also prompted hotels to invest in contingency planning, thus anticipating how the future may unfold and assigning specific roles and tasks within their organisations and beyond for appropriate response given the resources available. This can be referred to as the planning element of organisational resilience (Brown et al., 2017). Thus, it is argued that the level of organisational resilience to future external impacts may have influenced the scope of (current and future) measures adopted by hotels against the pandemic and determined the speed of their implementation (Prayag, 2020).

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) highlights the need for hotels, in addition to conserving the environment, to look after their customers, employees and local communities (Levy and Park, 2011). This need becomes especially prominent in the time of crises and disasters which exposes vulnerability of these categories of stakeholders (Henderson, 2007) and highlights the importance of hotels as ‘duty of care’ providers (Dobie et al., 2018). Hence, it is argued that the levels of CSR adopted by hotels prior to COVID-19 may have affected organisational resilience of hotels which is supported empirically by Lv et al. (2019) albeit not specifically in the hospitality context. This, in turn, may have impacted the range of (current and future) measures that hotels put in place in order to combat the negative implications of the pandemic for their business, as discussed above and reinforced by He and Harris (2020). Further, from the perspective of senior hotel managers, past CSR practices up-taken by their hotels may, therefore, influence their perceived job security and, subsequently, impacted their organisational commitment. This is confirmed in a recent study by Mao et al. (2020) who demonstrated the positive effect of CSR on self-efficacy, hope, resilience and optimism of tourism employees in China during the COVID-19 outbreak and showcased the inter-linkages between job satisfaction of staff and an organisational response to the pandemic.

The concepts of organisational resilience and CSR in the hotel sector, alongside the measures taken by specific hotel businesses to reduce the negative effect of COVID-19 on their customers and employees, are closely related to the organisational ‘capital’ paradigm. This is because the capacity of any organisation to adapt to crises and disasters and future organisational planning for such external disruptions requires a careful allocation of (physical, financial and labour) resources alongside their prioritisation in critical times (McManus et al., 2008). Likewise, the success of implementing CSR practices in hotels is underpinned by resource availability (Filimonau and Magklaropoulou, 2020). Resource constraints can, at least partially, explain, for example, why CSR practices are predominantly adopted by large(r), chain-affiliated, hotels whilst small(er), independent and/or family-run, hotel businesses often fail to demonstrate genuine engagement with the CSR agenda (Ettinger et al., 2018). The (current and future) resources available to an organisation describe this organisation’s ‘capital’, thus linking all these concepts/paradigms together (Leonidou et al., 2013).

Brown et al. (2019) distinguish between six types of organisational capital, namely economic, social, human, physical, natural and cultural. It is argued that some of these capital types overlap: for instance, cultural capital represents a logical product of social and human capital where the social networks created by an organisation and the skills of its employees offer adequate resources for disaster planning and management (Filimonau and De Coteau, 2020). Likewise, natural capital, which is largely expressed in the (dis)benefits of an organisation’s location, resembles, in a number of aspects, physical capital, which is mostly understood as the (dis)benefits attributed to an organisation’s size, especially in the context of those businesses based in urbanised and easily accessible areas, such as hotels. Indeed, most hotels tend to concentrate in popular tourist destinations and such dense concentrations have the potential to negate the (dis)beneficial effect of the locational factor (Gonzalez-Diaz et al., 2015). An explicit difference between physical and natural capital can only be observed in the case of businesses operating in remote destinations where the relative remoteness of the market may determine the size of its natural capital (Schmallegger and Carson, 2010). Regardless of any possible overlaps, Brown et al. (2019) claim that a truly integrative, multi-capital, perspective is necessary when designing a disaster management framework for hotels. This is because all capital types become critical for hotel businesses in order to plan, prepare, adapt and recover from external disruptions (Jiang et al., 2019). Indeed, it is fair to assume that the extent of the (current and future) measures that hotels implement in order to reduce the negative implications of the pandemic is dictated by their resource availability and, hence, by the instant access of the hotel business to various categories of its ‘capital’.

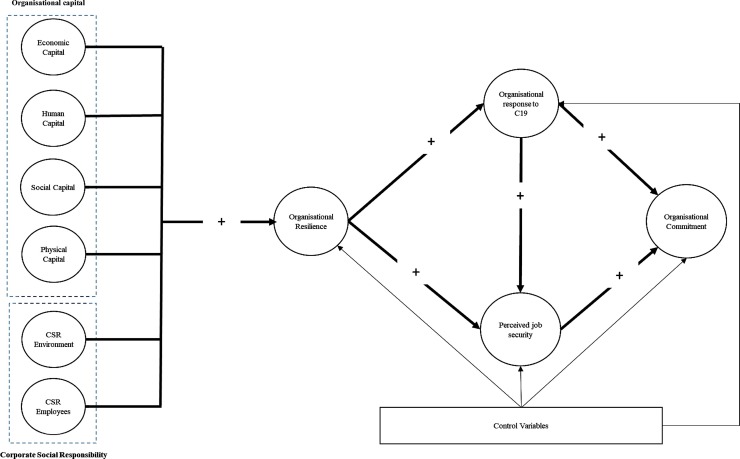

Drawing on the above theoretical premises, this study has set to explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on organisational commitment of senior hotel managers. To this end, it adopted an integrative, multi-capital, paradigm to predict the level of organisational resilience. It further considered the effect of the previously implemented CSR practices on organisational resilience of hotels. Lastly, organisational response of hotels to the pandemic was viewed as a product of organisational resilience and a mediator of perceived job security. All these constructs were subsequently utilised to explain organisational commitment of senior hotel managers. The research model of this study is presented in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Research model.

The contribution of this study to the current body of knowledge is, thus, in that it evaluates the cumulative effect of such critical elements of organisational performance as (1) organisational capital; (2) CRS; and (3) organisational resilience in light of (4) a disruptive event, i.e. the COVID-19 pandemic, with its foreseen impact on (5) perceived job security of senior hotel managers and (6) organisational commitment of senior hotel managers. Past research has demonstrated the significance of all these variables for hotel management separately, but never together and not in the context of a global disruptive event. It is argued that this study can, therefore, be used as a proxy to better understand the cumulative effect of some of the main determinants of effective organisational performance and employment in the hotel sector which is in order to model the future of the hotel business in light of the increasing frequency of disasters and crises. This particularly concerns the potential disruptions that can be imposed on hotels by climate change. It is argued that this study can enhance preparedness of the hotel sector to such disruptive events by attracting and retaining quality staff.

2. Research design

2.1. Design of the measurement instrument

The method of quantitative survey was adopted for data collection in order to achieve better generalisability and enhance representativeness of results. The survey questionnaire was developed following the literature review. It incorporated items that had either been taken directly or adapted from previous studies on the topic of organisational capital; CSR; organisational resilience; perceived job security and organisational commitment. These were supplemented with some ad-hoc items on preventative and protective measures adopted by hotels against COVID-19. More specifically:

The economic, social, human and physical dimensions of organisational capital were measured with the help of the items proposed by Brown et al. (2019). Specifically, 4 items were used to measure each dimension except human capital which included 5 items. CSR was measured with two dimensions, i.e. CSR-environment/community composed of 5 items and CSR-employees made up by 4 items, all proposed by Park and Levy (2014). The dimension CSR-consumers was excluded because the original study covered items measuring customer orientation not directly connected to the social responsibility aspects of hotel operations. Further, Lv et al. (2019) have shown that the environment and employee dimensions of CSR exert the largest effect on organisational resilience, thus providing another rationale for their adoption in this study. Following Lee et al.’s (2013) conceptualisation and measurement protocol, organisational resilience was conceived as a multidimensional construct composed by two dimensions named adaptive capacity and planning for resilience. Since the original scale included more than 40 items, measures with the highest factorial loadings were selected to study these dimensions. Specifically, the adaptive capacity dimension included 6 items and the planning capacity dimension was measured with 4 items. Perceived job security was measured with 4 items taken from Mohsin et al. (2013). Organisational commitment was measured with items proposed by Lee et al. (2001). Although three dimensions of organisational commitment can be distinguished, i.e. affective commitment, normative commitment and continuance, the latter dimension was excluded from analysis due to its low factorial loadings achieved in the original study of Lee et al. (2001). The affective and normative commitment dimensions had high factorial loadings; these were, therefore, retained and measured with 3 and 4 items, respectively.

Due to the novelty of the pandemic, there were no validated scales to measure organisational response of hotels to COVID-19. Measures for this variable were, therefore, purposefully developed. To this end, semi-structured interviews with three senior hotel managers were conducted in order to capture the range of measures used by hotels in Spain to adapt to the business disruption caused by the pandemic and plan for recovery. The interview findings were supplemented with a detailed content analysis of media stories, popular news, trade press and specialised webinars held by the Spanish hotel industry associations on the topic in question. As a result, two latent variables were designed. The first covered actions that were implemented by hotels during the emergency state of the pandemic (from hereafter labelled as current actions). The second included a list of actions planned by hotels to facilitate a rapid recovery post-lockdown (from hereafter labelled as future actions). The feasibility of all identified actions was tested in informal interviews held with five senior managers of Spanish hotels who confirmed their operational validity. Appendix A shows the measurement scales adopted in this study.

2.2. Questionnaire design

The questionnaire was developed in English (the language of the literature review) and back-translated in Spanish in line with the guidelines of Werner and Campbell (1973). The questionnaire was divided into three main blocks. The first block aimed to categorise hotels and, therefore, sought to gather information on their key characteristics (i.e. size, chain affiliation, existence of dedicated CSR and crisis management executives and/or departments, and scope of business operations), position of study informants within their respective organisations alongside their work experience in the hospitality industry. The middle block contained the measurement items capturing the latent variables of the model. Here, all items/variables were introduced in a random order to reduce the effect of common method bias and avoid respondents to infer causality and deduce the purpose of the model. All latent variables were measured with a 7-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree; 7 =strongly agree). The last block collected socio-demographic features of study informants (i.e. age, education and gender) and established hotel locations. The questionnaire was pre-tested on a small sample of hotel managers in Spain prior to field deployment.

2.3. Recruitment and data collection

Data were collected in May-June 2020 via an online survey of a sample of senior managers in Spanish hotels. Senior managers were specifically targeted due to their anticipated (better) knowledge which they should have possessed on the impact of COVID-19 on their respective organisations alongside the strategies implemented by their employers in order to adapt and recover. The target population was comprised of tourist accommodation facilities represented by comfort categories ranging from 1 to 5 stars and operating in all regions of Spain. Only one manager from each hotel was invited to participate in the study.

To recruit willing participants, hotel contact details were obtained from hotel databases published by the regional governments of Spain, but also from open business databases and trade publications of different hotel guilds and hotel industry associations in Spain. Circa 4500 email contacts were made through these media. As the data were collected during the national lockdown imposed by the Spanish government to prevent the spread of the pandemic, which ceased operations of most hotels, managers were also recruited via professional hotelier networks set on LinkedIn. Circa 1200 LinkedIn contacts were made. Initially, generic emails/messages were sent to all prospective contacts explaining the goal of the study. This was followed up with more personalised emails/messages that provided detailed information about the project aiming to increase the response rate. At this stage, to reduce the negative effect of social desirability biases, prospective participants were guaranteed complete confidentiality and anonymity. An option of seeing an end-of-the-project report with this study’s results was also offered to all prospective study informants.

In total, 358 responses were collected. After the initial screening, some questionnaires were discarded as they were either incomplete or provided incoherent responses. The final sample was composed of 244 valid questionnaires. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample obtained.

Table 1.

Profile of the studied sample.

| Gender | Position | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CEO/Owner | 27.2 % | ||

| Male | 60.5 % | Director | 38.7 % |

| Female | 38.5 % | Department/Section manager | 13.6 % |

| Others/Prefer not to say | 1% | Head of Reservations | 9.1 % |

| Other senior role (e.g. Operations Manager) | 11.5 % | ||

| Highest level of education achieved | Hotel rating | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary-Secondary | 4.9 % | Hostel/Aparthotel | 8.5 % |

| Vocational training | 16.5 % | 1 or 2 stars | 20.0 % |

| University degree | 49.5 % | 3 stars | 16.2 % |

| Master or superior | 28.2 % | 4 stars | 37.7 % |

| Others | 1% | 5 stars and above | 17.7 % |

| Number of rooms | Number of employees | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 20 | 25.2 % | ||

| 21−40 | 11.6 % | Less than 10 | 31.3% |

| 41−80 | 15.1 % | 11−49 | 23.0% |

| 81−120 | 17.1 % | 50−249 | 21.4% |

| 21−200 | 11.6 % | 250+ | 24.3 % |

| More than 200 | 19.4 % | ||

| Affiliation with a chain | Geographical scope of business operations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Operates only in Spain | 55.0 % | ||

| Yes | 51 % | Operates in Spain and Portugal | 2.9 % |

| No | 49 % | International scope of operations (3 countries or more) | 42.1 % |

| Person/Department in charge of CSR | Person/Department in charge of Crisis Management | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, dedicated post/unit | 17.5 % | Yes, dedicated post/unit | 8.7 % |

| Yes, but not a dedicated post | 64.6 % | Yes, but not a dedicated post | 75.1 % |

| No/I do not know | 17.9 % | No/I do not know | 16.2 % |

| Tenure | Work experience in the Hospitality industry | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than a year | 8.7 % | Less than a year | 0.8 % |

| 1−3 years | 21.5 % | 1−3 years | 4.5 % |

| 4−10 years | 31.8 % | 4−10 years | 19.8 % |

| More than 10 years | 38.0 % | More than 10 years | 74.9 % |

3. Analysis and results

Partial Least Squares (PLS) path modelling was employed to test the research model. The choice of this method was driven by the following considerations. First, the study is predictive-explanatory which fits the context of PLS (Henseler, 2018). Second, the sample (n = 244) is not very large but suits the sample size requirements set for PLS. Third, the model is complex since it includes direct and indirect relationships in order to predict dependent latent variables, the task which PLS is capable of handling effectively (Cepeda-Carrion et al., 2019). Fourth, the research topic is novel, with limited theoretical development, whilst the model combines the previously validated measurement instruments with those developed ad-hoc for a specific purpose of this study. PLS has proven its effectiveness when applied in such novel research contexts in the past, including the sector of hospitality (see, for example, Filimonau et al., 2020a). Fifth, the model incorporates first-order latent variables and second-order (multidimensional) variables. The estimation of these multidimensional constructs requires the implementation of a two-stage approach which PLS can deliver effectively (Henseler et al., 2016). Lastly, the nature of most latent variables is compatible with a composite measurement model handled by PLS (Dijkstra and Henseler, 2015). Specifically, this model combines constructs compatible with composite reflective models (mode A) (i.e. the dimensions of organisational capital, perceived job security and organisational commitment) and composite formative construct (mode B) (i.e. the dimensions of organisational response to COVID-19). Table 2 summarises the measurement models of the variables included in the study. The PLS analysis was implemented through the SmartPLS v3.2 software (Ringle et al., 2015).

Table 2.

Measurement models.

| First-order latent variables | First-order measurement model | Second-order latent variables | Second-order measurement model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic capital | Composite type A | n/a | n/a |

| Social capital | Composite type A | n/a | n/a |

| Human capital | Composite type A | n/a | n/a |

| Physical capital | Composite type A | n/a | n/a |

| Corporate Social Responsibility-Employees | Composite type A | n/a | n/a |

| Corporate Social Responsibility-Environment/Community | Composite type A | n/a | n/a |

| Resilience-Adaptive capacity | Composite type A | Organisational resilience | Composite type A |

| Resilience-Planning | Composite type A | ||

| Organisational response to COVID-19-Current actions | Composite type B | Organisational response to COVID-19 | Composite type B |

| Organisational response to COVID-19-Future actions | Composite type B | ||

| Perceived Job Security | Composite type A | n/a | n/a |

| Affective organisational commitment | Composite type A | Organisational commitment | Composite type A |

| Normative organisational commitment | Composite type A |

3.1. Assessment of the measurement model

The two-stage approach to modelling multidimensional constructs requires an initial estimation in order to obtain the latent variable scores of the second-order constructs. As a result of this estimation, the reflective measurement models in mode A were assessed by examining the individual reliability of the items, composite reliability and convergent and discriminant validity. As recommended by Hair et al. (2019), all factorial loadings were above 0.708, which guaranteed the individual reliability of the items. In addition, the composite reliability index and the recently introduced measure Rho_A (Dijkstra and Henseler, 2015) were both above a critical threshold of 0.7. Convergent validity of the constructs was examined through the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) metric, which was above 0.5 and in line with Hair et al. (2017). Finally, discriminant validity was examined through the accurate Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratios approach (Henseler et al., 2015). The HTMT values below 0.9 demonstrated the existence of discriminant validity. However, discriminant validity for the affective and normative dimensions of organisational commitment was not established since the HTMT-ratio presented a value of 0.944. Consequently, this construct was re-considered as a first-order type A measurement model composed of the seven items included to measure the two dimensions of organisational commitment. For the mode B composites, collinearity between the formative indicators was explored and the significance and relevance of the outer weights were assessed (Cepeda-Carrion et al., 2019). The variance inflation factor (VIF) of the indicators was below a critical threshold of 3.3 (Hair et al., 2019). All the outer weights presented values between 0.172 and 0.358 and all were statistically significant at p < 0.05.

The estimation and validation of the first-order measurement model provided the latent variable scores to estimate the second-order factors of the model. The results of this estimation are shown in Table 3 . The indicators and dimensions of the mode A composites satisfied the reliability and validity requirements. All composite reliability indicators were above a suggested threshold of 0.7 and the AVE critical value of 0.5 was achieved in all instances. The factorial loadings were all above 0.7. Therefore, all multidimensional constructs and dimensions attained construct reliability and convergent validity. As shown in Table 4 , all variables presented discriminant validity following the HTMT criterion (Henseler et al., 2015). The results also confirmed the validity of the second-order type-B measurement model as VIF of the indicators was below a critical threshold of 3.3 whilst all outer weights were statistically significant (p < 0.05) with relevant values to explain the latent variables.

Table 3.

Measurement model.

| First-order construct | Indicator | Standardised Loading/ Weight | Rho_A | Composite Reliability Index (CRI) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic capital (ECOK) | ECOK1 | 0.883 | 0.869 | 0.902 | 0.698 |

| ECOK2 | 0.830 | ||||

| ECOK3 | 0.755 | ||||

| ECOK4 | 0.868 | ||||

| Social capital (SOCK) | SOCK1 | 0.830 | 0.865 | 0.909 | 0.714 |

| SOCK2 | 0.894 | ||||

| SOCK3 | 0.776 | ||||

| SOCK4 | 0.874 | ||||

| Human capital (HUMK) | HUMK1 | 0.891 | 0.939 | 0.951 | 0.795 |

| HUMK2 | 0.901 | ||||

| HUMK3 | 0.905 | ||||

| HUMK4 | 0.899 | ||||

| HUMK5 | 0.862 | ||||

| Physical capital (PHYK) | PHYK1 | 0.899 | 0.919 | 0.941 | 0.799 |

| PHYK2 | 0.888 | ||||

| PHYK3 | 0.880 | ||||

| PHYK4 | 0.908 | ||||

| CSR-Environment/Community (CSRENV) | CSRENV1 | 0.876 | 0.891 | 0.917 | 0.689 |

| CSRENV2 | 0.870 | ||||

| CSRENV3 | 0.778 | ||||

| CSRENV4 | 0.824 | ||||

| CSRENV5 | 0.798 | ||||

| CSR-Employees (CSREMP) | CSREMP1 | 0.913 | 0.906 | 0.932 | 0.775 |

| CSREMP2 | 0.892 | ||||

| CSREMP3 | 0.822 | ||||

| CSREMP4 | 0.892 | ||||

| Organisational response to COVID-19 (RESP) | CURR | 0.675 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| FUT | 0.524 | ||||

| Organisational Resilience (RESIL) | ADAP | 0.951 | 0.900 | 0.952 | 0.908 |

| PLAN | 0.955 | ||||

| Perceived Job Security (SECUR) | SECUR1 | 0.844 | 0.889 | 0.923 | 0.749 |

| SECUR2 | 0.910 | ||||

| SECUR3 | 0.810 | ||||

| SECUR4 | 0.894 | ||||

| Organisational Commitment (COMM) | AFF1 | 0.848 | 0.946 | 0.950 | 0.730 |

| AFF2 | 0.856 | ||||

| AFF3 | 0.905 | ||||

| AFF4 | 0.874 | ||||

| NOR1 | 0.768 | ||||

| NOR2 | 0.893 | ||||

| NOR3 | 0.832 |

Table 4.

Discriminant validity of the measurement model.

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ECOK | ||||||||

| 2. SOCK | 0.788 | |||||||

| 3. HUMK | 0.751 | 0.805 | ||||||

| 4. PHYK | 0.744 | 0.720 | 0.817 | |||||

| 5. CSRENV | 0.490 | 0.517 | 0.578 | 0.551 | ||||

| 6.CSREMP | 0.315 | 0.442 | 0.459 | 0.539 | 0.623 | |||

| 7.RESIL | 0.649 | 0.660 | 0.788 | 0.707 | 0.720 | 0.709 | ||

| 8. SECUR | 0.565 | 0.430 | 0.457 | 0.473 | 0.257 | 0.322 | 0.606 | |

| 9. COMM | 0.236 | 0.237 | 0.383 | 0.341 | 0.409 | 0.525 | 0.641 | 0.428 |

Note 1: Figures in the diagonal represent the AVE values. Off-diagonal figures represent the constructs’ squared correlations.

Note 2: See Table 3.

3.2. Assessment of the structural model

The potential existence of collinearity issues among the exogeneous latent variables was first assessed. This analysis revealed that the VIF values were all below 3.28 which is lower than a suggested threshold of 5 or, ideally, 3.3 (Hair et al., 2019), thus indicating that collinearity was not an issue in this study. Next, to check the significance of the structural parameters, since all variables were expected to be positively correlated and, therefore, a sign of the causality was pre-determined, a one-tailed bootstrapping test with 8.000 subsamples was implemented. To test the effect of the control variables, a complementary two-tails test was applied. The predictive relevance of the model was examined with the R2 of the endogenous latent variables. In this case, all R2 values were above a critical threshold of 0.05 with the minimum value being 0.199. Predictive relevance was also confirmed since all Q2 values were positive. Following Aguirre-Urreta and Rönkkö (2018)’s recommendations, in terms of statistical inference, the bootstrapped percentile confidence intervals were also examined to establish the significance of the structural parameters. Table 5 shows the results of the estimation of the structural model.

Table 5.

Results of the structural model.

| Relationship | β | t-value | PCI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Capital → Organisational Resilience | 0.163 | 2.710* | (0.071; 0.271) |

| Social Capital → Organisational Resilience | −0.007 | 0.120 | (−0.119; 0.086) |

| Human Capital → Organisational Resilience | 0.401 | 4.742* | (0.264; 0.541) |

| Physical Capital → Organisational Resilience | 0.014 | 0.166 | (−0.123; 0.156) |

| CSR Environment/Community → Organisational Resilience | 0.213 | 3.477* | (0.114; 0.313) |

| CSR Employees → Organisational Resilience | 0.292 | 4.644* | (0.186; 0.393) |

| Organisational Resilience → Organisational Response COVID-19 | 0.555 | 10.007* | (0.456; 0.639) |

| Organisational Resilience → Perceived Job Security | 0.458 | 6.526* | (0.339; 0.573) |

| Organisational Response COVID-19→ Perceived Job Security | 0.146 | 2.008** | (0.020; 0.259) |

| Perceived Job Security → Organisational Commitment | 0.416 | 7.004* | (0.310; 0.506) |

| Control relationships | β | t-value | PCI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of employees → Organisational Resilience | −0.094 | 2.204** | (−0.167; −0.027) |

| Number of employees → Organisational Response COVID-19 | 0.093 | 1.475 | (−0.015; 0.191) |

| Number of employees → Perceived Job Security | −0.004 | 0.076 | (−0.099; 0.091) |

| Number of employees → Organisational Commitment | −0.197 | 3.212* | (−0.296; −0.093) |

| Tenure → Perceived Job Security | 0.004 | 0.470 | (−0.125; 0.059) |

| Tenure → Organisational Commitment | −0.041 | 0.219 | (−0.076; 0.109) |

| Age → Perceived Job Security | −0.116 | 2.039** | (−0.210; −0.024) |

| Age → Organisational Commitment | 0.169 | 2.689* | (0.061; 0.269) |

| R2(RESIL) = 0.703; R2(RESP) = 0.329; R2(SECUR) = 0.310; R2(COMM) = 0.199 | |||

| Q2(RESIL) = 0.622; Q2(RESP) = 0.216; Q(SECUR) = 0.221; Q2(COMM) = 0.136 | |||

Note 1: * p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05.

Note 2: See Table 5.

3.3. Interpretation of results

The estimation of the structural model revealed interesting insights into how organisational resources impacted organisational resilience of hotels. First, human capital was a predictor exerting the largest impact on organisational resilience (β = 0.401; t-value = 4.742) followed by economic capital (β = 0.163; t-value = 2.710). Surprisingly, hotels with large social (β=−0.007; t-value = 0.120) and physical (β = 0.014; t-value = 0.166) resources did not necessarily demonstrate high organisational resilience. In addition, both CSR dimensions imposed a positive and significant effect on organisational resilience. Thus, those hotels that took more proactive stances on the adoption of CSR practices related to the environment/community (β = 0.213; t-value = 3.477) and employees (β = 0.292; t-value = 4.644) were also found to be more resilient.

Focusing on the outcomes of organisational resilience, the results suggested, rather logically, that more resilient hotels were more active in implementing effective responses towards the COVID-19 crisis (β = 0.555; t-value = 10.007). This confirms that organisational resilience facilitates the response capacity of hotels towards the current pandemic, but also any future disastrous events and crises, through the careful implementation of actions that can guarantee business survival in the long(er) term. In addition, managers perceived that their job security directly depended on the organisational resilience capacity of hotels (β = 0.458; t-value = 6.526) and the (current and future) actions undertaken by hotels in response to the COVID-19 crisis (β = 0.146; t-value = 2.008). Higher levels of perceived job security after the pandemic were also positively and significantly associated with organisational commitment (β = 0.416; t-value = 7.004). This suggested that managers would be more likely to affectively and normatively commit to their organisations if they perceived that hotels were pro-actively investing in the necessary resources, adopting CSR practices and applying the required actions to guarantee job security during and after the COVID-19 crisis.

Regarding the effect of the control variables, the estimations indicated that organisational resilience decreased with increasing number of employees (β=−0.094; t-value = 2.204), thus potentially suggesting that large(r) hotels may have had less flexibility in dealing with the COVID-19 crisis. Furthermore, organisational commitment decreased for large(r) hotels (β=−0.197; t-value = 3.212) which might, in part, be attributed to the low(er) organisational resilience as highlighted above. In terms of socio-demographic data, older managers had the perceptions that their jobs would be less secure after the pandemic (β=−0.116; t-value = 2.039) but presented higher levels of organisational commitment towards their hotels (β=−0.169; t-value = 2.689).

3.4. Ex-post complementary analyses

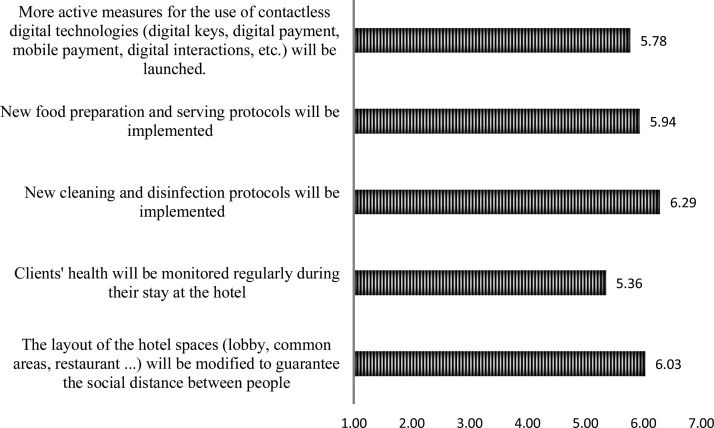

Given the topical novelty of the study, complementary descriptive, ANOVA and means differences, analyses were applied to further explore organisational resilience and organisational response of Spanish hotels to COVID-19 and investigate the influence of various features of studied hotels on these variables. Specifically, it was examined if both dimensions of organisational resilience and both dimensions of organisational response to COVID-19 presented statistical differences according to the hotel chain affiliation, geographical scope of business operation, presence of a dedicated CSR executive/department or presence of a dedicated crisis management executive/department. Results of these descriptive analyses are presented in Fig. 2, Fig. 3 and Table 6 .

Fig. 2.

Organisational response to COVID-19-Current actions.

Fig. 3.

Organisational response to COVID-19-Future actions.

Table 6.

Organisational resilience of hotels, their response to the COVID-19 crisis and key business characteristics.

| Variable | Chain affiliation |

Mean analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | t-value (Sig.) | |

| Organisational Resilience-Adaptive capacity | 4.634 | 4.493 | 1.237 (0.217) |

| Organisational Resilience-Planning | 5.526 | 5.077 | 2.842 (0.005) |

| Organisational response to COVID-19-Current actions | 4.654 | 4.276 | 2.370 (0.019) |

| Organisational response to COVID-19-Future actions | 6.173 | 5.577 | 4.288 (0.000) |

| Variable | Geographical Scope of Operations |

Mean analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | International | t-value (Sig.) | |

| Organisational Resilience-Adaptive capacity | 4.441 | 4.693 | 2.177 (0.031) |

| Organisational Resilience-Planning | 5.045 | 5.590 | 3.403 (0.001) |

| Organisational response to COVID-19-Current actions | 4.345 | 4.595 | 1.534 (0.127) |

| Organisational response to COVID-19-Future actions | 5.620 | 6.197 | 4.049 (0.000) |

| Variable | CSR Executive/Department |

ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, full dedication | Yes, partial dedication | No/Do not know | F(Sig.) | |

| Organisational Resilience-Adaptive capacity | 4.977 | 4.487 | 4.977 | 5.396 (0.005) |

| Organisational Resilience-Planning | 4.482 | 4.569 | 4.864 | 5.397 (0.005) |

| Organisational response to COVID-19-Current actions | 5.152 | 4.411 | 4.015 | 12.294 (0.000) |

| Organisational response to COVID-19-Future actions | 6.276 | 6.276 | 5.478 | 9.941 (0.000) |

| Variable | Crisis Management Executive/Department |

ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, full dedication | Yes, partial dedication | No/Do not know | F(Sig.) | |

| Organisational Resilience-Adaptive capacity | 5.070 | 4.604 | 4.112 | 9.052 (0.000) |

| Organisational Resilience-Planning | 6.210 | 5.389 | 4.419 | 17.641 (0.000) |

| Organisational response to COVID-19-Current actions | 5.111 | 4.554 | 3.692 | 11.338 (0.000) |

| Organisational response to COVID-19-Future actions | 6.470 | 6.270 | 5.948 | 9.990 (0.000) |

Regarding organisational response of hotels to the COVID-19 crisis, descriptive analysis revealed that, during the lockdown period, most hotels focused their actions on the reimbursement of customer cancelations and/or release of compensation vouchers for cancelled holidays (Fig. 2). Noticeable is that some hotels attempted to manage food surplus to reduce wastage, thus saving resources, and support their employees with financial aid or by providing temporary jobs. As for the future actions (Fig. 3), most hotels focused on the development and implementation of new cleaning protocols and the re-design of the building layout in line with social distancing rules. Noticeable is interest of many hotels in the adoption of new food preparation and serving protocols, application of new technologies and digital tools aiding in the reduction of human contact and, to a lesser extent, in pro-active monitoring of customer health during their stay.

Regarding the role of the key features of studied hotel businesses (Table 6), the results demonstrated that chain-affiliated hotels showcased higher levels of planning for organisational resilience, implemented more (current) actions in response to COVID-19 and declared their intention to adopt more (future) actions. However, no statistical difference was detected between affiliated and non-affiliated hotels regarding their adaptive capacities as a mediator of organisational resilience. Hotels with an international scope of operations were found to be more resilient in general and planned to implement more future actions in response to the COVID-19 crisis compared to hotels operating domestically. However, no significant differences between international and domestic hotels were recorded in terms of their current actions adopted to respond to the pandemic. Finally, ANOVA analysis revealed that the presence of a fully dedicated executive/department of CSR and/or crisis management could explain (better) organisational resilience of hotels and predict more active implementation of current and future actions to manage the COVID-19 crisis.

4. Discussion

The study demonstrated the important role of organisational capital in making hotel businesses more resilient to crises and disasters. This confirms, in part, the propositions made by Biggs et al. (2012); Brown et al. (2018) and Hall et al. (2018) who all discussed the need for tourism and hospitality organisations to source out the different types of resources in order to withstand the detrimental impacts of disastrous events. However, unlike past research, this study recorded a limited effect of social and physical capital on organisational resilience of hotels in Spain.

The limited role of social capital can be partially explained by the high competitiveness of the hotel industry which prevents collaboration of hotel businesses and hampers the development of strong hotel networks that could be utilised to request/provide help to its members in the times of crisis (Von Friedrichs Grängsjö and Gummesson, 2006). Another possible explanation is in the restricted flows of information prevalent within the hotel industry which impedes knowledge exchange between hoteliers, thus weakening their capacity to learn from each other but also from past crises/disastrous events and to adapt to their future occurrences (Kim et al., 2013). As Sigala (2020) posits, in a post-pandemic world, there is a need for hoteliers to re-consider the way how they have operated to date, so that they could drop a ‘silo mentality’ and gradually transit from competition towards (more) collaboration, or even coopetition. Such transition will increase the social capital of hoteliers, thus aiding them in better planning for and recovering from future external disruptions, be it the subsequent waves of COVID-19 or any other natural or man-made disasters.

The limited effect of physical capital can be partially explained by the novelty of the COVID-19 crisis. Indeed, past emergency and/or crisis management protocols adopted by Spanish hotels were possibly only tailored towards economic and/or political shocks and, to a lesser degree, potential acts of terrorism (see, for example, Perles-Ribes et al., 2016). Given that Spain is generally not vulnerable to disastrous events, local hotels may have failed to assign the necessary importance to the infrastructure and technologies required to withstand external disruptions. To some extent, this is confirmed by the descriptive analysis held in this study which demonstrated that hotels with an international scope of business operations were more pro-active in the implementation of current and future anti-COVID-19 actions. This may be, in part, attributed to the need of such hoteliers to better account for a larger number of uncertainties and contingencies existing across various markets in which they operate, thus making every effort to secure the necessary physical resources for better preparedness and forward planning (Liu, 2017).

The effect of human capital on organisational resilience of hotels is notable and should be emphasized. The importance of employees for hotel businesses in general (Baum and Hai, 2020) and for business performance in the times of crises and disasters has long been acknowledged (Nilakant et al., 2013). This study demonstrated that Spanish hotels should pro-actively invest into their human resources in order to ensure they have a ‘right’ combination of expertise and skills to plan for future disastrous events and withstand their negative consequences. From the viewpoint of future organisational commitment it is also critical that hotels should not be tempted to make staff redundant during the crisis. Even though this may be considered a rather logical solution to the immediate cost minimization/optimization which is necessary to keep a hotel business afloat, staff redundancies will reduce human capital of organisations, thus diminishing their long-term organisational resilience. This may become fatal for hotels if one disaster follows another such as, for example, in the case of a second pandemic wave. This may become especially detrimental in the case of consecutive disastrous events with their substantial negative cascading effects, such as climate change (Pescarolli and Alexander, 2016).

A link between CSR practices adopted by hotels and their organisational resilience was established. Arguably, this is a key finding of this study which shows that hotels should be investing into CSR to improve their chances to withstand future crises and disasters. This is in line with Mao et al. (2020) who showcased this connection by highlighting the role of CSR practices in enhancing job satisfaction and improving work productivity of tourism employees. Given that staff is a cornerstone of human capital of any organisation (Brown et al., 2019), which exerts direct influence on its resilience, as discussed earlier, hotels should more pro-actively engage in CSR in light of future disastrous events, such as climate change, for example. As Lv et al. (2019) argue, this will not only improve disaster resilience of any business, but can also refine its long-term financial performance.

Mao et al. (2020) indicated how CSR can contribute to the satisfaction of tourism staff with an organisational response to COVID-19. This study adds to Mao et al. (2020)’s findings by demonstrating that this contribution may not necessarily be direct, but mediated via employee perception of enhanced organisational resilience. Indeed, the range of (current and future) actions adopted by Spanish hotels to withstand the COVID-19 crisis was linked to their organisational capital. This is because this capital, especially human, provides the necessary creativity and offers the required skillsets for organisations to better prepare and plan for possible shocks and disasters (Brown et al., 2018). On this basis, it can be concluded that hotels with larger capitals and, consequently, higher levels of organisational resilience, hold a better probability to survive a second wave of the pandemic if/when it comes.

The study found that organisational resilience directly, but also via the adopted anti-COVID-19 actions, affected perceived job security of senior hotel managers. This is understandable as available resources, past corporate commitment to safeguard the well-being of employees as exemplified, for example, by the extent of the CSR adoption, and the measures put in place to ensure the business resumes and goes back to ‘normal’ provide hotel managers with the necessary reassurance that their positions are safe. Past research has highlighted that organisations demonstrating corporate adherence to business and staff success and regularly communicating to their employees the plans and procedures they have implemented for business longevity are characterised by higher rates of staff retention (Mazzei et al., 2012; Mao et al., 2020). This paper, therefore, adds further evidence to this knowledge with a case study of Spanish hotels.

Perceived job security was directly linked to organisational commitment of hotel managers. This is, again, rather understandable given that the psychological feeling of being safe from possible redundancies that are normal in the times of crisis can motivate staff to work harder (Markovits et al., 2014). The contribution of this study to knowledge is in the demonstrated effect imposed on perceived job security by such variables as the (different types of) organisational capital and CSR, mediated via organisational resilience. In essence, it showed that organisational commitment of senior managers in general, but especially in the times of crises and disasters, can be secured by investing into their personal and professional development (human capital) and subjective well-being (CSR).

The study revealed the effect of different operational and socio-demographic variables on organisational resilience, perceived job security and organisational commitment in the hotel industry. The operational scope and chain affiliation of hotels were found to correlate with organisational resilience as international and chain-affiliated businesses proved to be more resilient in general. As discussed earlier, this can be linked to better human, social, economic and physical capital of these organisations, but also attributed to their better ‘open-mindedness’ (Eggers, 2020). Indeed, domestic hotels and/or the independents may be unlikely to invest resources into crisis and disaster management beyond a ‘bare minimum’ given that they have to prioritize other operational tasks, such as revenue generation and customer retention (Sawalha, 2015). They also have restricted access to the cutting-edge ‘know how’ given their professional networks are under-developed and, often, non-existent (Hall et al., 2018). This highlights scope for policy-making interventions. These interventions should consider offering tailor-made training opportunities to those (domestic and/or independent) hoteliers interested in crisis and disaster management. During these training events, international and chain-affiliated hotels can share best practices in disaster preparedness and recovery. Thus, the trainings, besides increasing the human capital of organisations through knowledge provision and co-creation, can also reinforce social capital via shaping local hotelier networks, thus building capacity to withstand future shocks and disastrous events.

Somewhat surprisingly, larger hotels demonstrated lower levels of organisational resilience. This can be partially attributed to the relative ‘bulkiness’ and ‘inflexibility’ of such organisations where vertical, hierarchical, management structures can slow down the flows of information, thus restricting knowledge exchange across various levels of decision-making and, potentially, reducing the positive effect of (larger) organisational capital (Hodari and Sturman, 2014). This is partially confirmed by the fact that the larger hotels in the studied sample with the better adoption of CSR practices showcased higher than average levels of organisational resilience. In theory, this may suggest that CSR may at least partially offset the negative impact of inflexible and bulky hotel management structures. Future research should, however, examine this point in more detail.

Senior managers in larger hotels were found to have lower levels of organisational commitment. This can be attributed to the vertical management structure of such hotels, as per above, which is a known job demotivator (Giudici and Filimonau, 2019). The flat structures of smaller hotels can, therefore, be seen as more attractive. A more ‘humane’ touch in the form of more personalized/sympathetic human resources management (Carnevale and Hatak, 2020) and staff empowerment may increase organisational commitment of senior hotel managers in larger organisations in the times of crisis.

Although older managers had lower perceptions regarding their job security in a post-pandemic world, they showcased high levels of organisational commitment. Given that older managers, throughout their professional careers, are likely to have gained extensive experience in crisis and disaster management (Filimonau and De Coteau, 2020), they can enhance the (human) capital of hotels, thus making them more prepared for future shocks and disastrous events. It is, therefore, argued that such managers should be retained by Spanish hotels especially in the light of the probability of a second pandemic wave.

5. Conclusions

This study measured the impact of organisational capital, CSR practices and organisational resilience on perceived job security and subsequent organisational commitment of senior hotel managers in Spain. The assessment was performed through the lens of the COVID-19 pandemic with its anticipated detrimental effect on profitability of hotel businesses and attractiveness of hospitality occupations. The study established an important role of CSR in building organisational resilience and, consequently, shaping hotel’s response to the COVID-19 crisis but also any prospective shocks and disastrous events that may disrupt the hotel industry in the future. Importantly, investment of hotels in CSR was shown to be beneficial not only from the viewpoint of enhanced organisational resilience, but also from the perspective of improved (perceived) job security and organisational commitment of senior hotel managers.

The validity of this study’s findings extends, therefore, beyond the (possibly temporary) impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and Spain as a geographical market in which the assessment was undertaken. Climate change represents a global societal challenge which is rapidly unfolding, thus holding potential to detrimentally impact the hotel industry in the foreseeable future. Hotels adopting CSR practices in a more pro-active and effective manner will not only increase their competitiveness in the domestic and international (labour) market, but can also enhance their resilience towards the forthcoming environmental changes. Adoption of CSR is of particular relevance to hotels operating in the destinations prone to a larger number of political and socio-economic shocks (for instance, countries of South America and/or Africa) and consecutive natural disasters (for example, Indonesia and the Philippines with their regular earthquakes, tsunamis and volcano eruptions). In these destinations, investment in CSR can enable hotels to retain qualified staff, thus building their organisational capital and reinforcing their organisational resilience in light of external disruptions.

The study holds a number of theoretical implications. First, it contributes to theory of organisational resilience by extending its application to the context of global disruptive events in the hotel sector. Whilst past research had considered organisational resilience of hoteliers in light of disasters and crises, these disastrous events were largely localised and imposed limited impact on the entire, (inter)national hotel sector. Organisational resilience of hotels in the context of a truly global disaster/crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, has never been studied despite the importance of such research in view of unfolding climate change with its anticipated detrimental effects on the global hotel sector. Second, the study contributes to theory of CSR by demonstrating the significance of adopting CSR practices by hoteliers as a means of increasing their organisational resilience in light of future disastrous events. Although past research has repeatedly indicated the role of CSR in building corporate image of hotels and improving their customer loyalty, this study showcases its importance for effective disaster and crisis management in the hotel sector. Further, this study highlights the significant role of CSR in improving perceived job security among senior hotel managers. This underlines the contribution made by this study to theories of human resources management and talent management in hotels. The case study of the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates that the adoption of CSR practices by hoteliers extends beyond reputational gains and customer loyalty. Instead, it holds important implications for retaining quality hotel staff by enhancing their confidence in the hotel sector and particular hotel businesses operating within as ‘caring’ and ‘responsible’ employment providers. Lastly, the study contributes to theory of organisational commitment in the hotel sector by showcasing the cumulative impact of CSR practices, organisational resilience and effective organisational response to a disaster/crisis on perceived job security of senior managers. This highlights the critical range of operational areas that hoteliers should focus on in order to retain employees and increase their organisational loyalty. This will become particularly important in the foreseeable future given the magnitude and frequency of global disastrous events are anticipated to increase with their potential, negative impact on the (inter)national hotel sector.

The study outlined a number of implications for hotel managers. First, it showed the need for them to invest in CSR not only as a means of improving their corporate brand, enhancing loyalty of current customers and attracting new consumers but also as a vehicle of building organisational resilience and, consequently, strengthening perceived job security of staff, thus retaining best employees in the times of disasters and crises. Second, the study demonstrates the need for hoteliers to invest in building human and economic capital in order to (better) prepare for future disastrous events. Not only this investment will increase organisational resilience of the hotel sector and individual hotel businesses, but can also enhance perceived job security of staff, thus contributing to their organisational loyalty. Lastly, the study indicates that organisational response to any disasters and crises should be timely, transparent and robust. Employees should be routinely informed of the anti-disaster/crisis measures adopted by hoteliers and the reasons for their adoption should be meticulously explained. This will provide hotel employees with the necessary reassurance of their (current and future) job security, thus improving their retention and enhancing their organisational commitment.

As with any research, this one had a number of limitations. The sample size was on a ‘thinner’ side and, whilst being sufficient to test the research model, it can be increased. Further, the online survey administration adopted due to the lockdown restrictions implied possible issues with data collection. Although the responses were quality checked for coherence, no control was possible over how these were provided. Lastly, given that this study recruited informants via hotel databases and LinkedIn, there was a probability that it did not reach for those hoteliers whose online presence was restricted.

The study outlined a number of interesting research opportunities. First, it did not test the effect of the CSR-Customers dimension and it would be interesting to see if/how its addition might change the outcome of the measurement model. Second, organisational resilience is a complex and multi-dimensional construct. Future studies should look into how other dimensions of organisational resilience affect perceived job security and organisational commitment of hotel managers. For example, the Silo mentality indicator of the Adaptive capacity dimension would be an interesting variable to test in more detail given that such mentality prevails within the hotel industry. Likewise, the Recovery priorities indicator of the Planning dimension should be studied in depth given that hotels tend to be short-sighted in that they only plan for the immediate recovery rather than for the long-term disaster preparedness. Lastly, whilst this study focused only on senior hotel managers in Spain it provided scope for future comparative research. This research can compare organisational commitment of senior hotel managers against junior/middle level managers or even front-of-house and back-of-house employees. Likewise, it can run a comparison of Spain with other hotel/tourism markets, especially those that have suffered from disastrous events in the past. Lastly, a comparative analysis of the hotel sector with other sectors of economic activity, in Spain and beyond, could be conducted.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Viachaslau Filimonau: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing - original draft. Belen Derqui: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Jorge Matute: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Appendix A. Measurement scales

| Economic capital | ||

|---|---|---|

| ECOK1 | My organisation has adequate resources to withstand Covid19 crisis. | Brown et al. (2018; 2019) |

| ECOK2 | My organisation has access to adequate finance to help it overcome Covid19 crisis. | |

| ECOK3 | The diverse customer base of my organisation will aid it in overcoming the implications of Covid19 crisis. | |

| ECOK4 | The size of my business will help it overcome Covid19 crisis. | |

| Social capital | ||

|---|---|---|

| SOCK1 | The people this organisation employs will help it overcome Covid19 crisis. | Brown et al. (2018; 2019) |

| SOCK2 | The industry connections this organisation has will help it overcome Covid19 crisis. | |

| SOCK3 | Past knowledge of disasters / crises will help this organisation overcome any disaster/crisis | |

| SOCK4 | Communication with customers, employees and other organisations will help this organisation overcome this crisis | |

| Human capital | ||

|---|---|---|

| HUMK1 | In this organisation there is sufficient knowledge to overcome this crisis | Brown et al. (2018; 2019) |

| HUMK2 | In this organisation there are sufficient skills to overcome this crisis | |

| HUMK3 | In this organisation there is sufficient capacity to adapt to the effect of this crisis | |

| HUMK4 | In this organisation there is strong leadership to overcome Covid19 crisis. | |

| HUMK5 | In this organisation there is adequate access to sufficient human resources to overcome Covid19 crisis. | |

| Physical capital | ||

|---|---|---|

| PHYK1 | In our organisation, we have adequate emergency protocols to adopt to Covid19 crisis. | Brown et al. (2018; 2019) |

| PHYK2 | In our organisation, we have adequate technical systems / technology to overcome Covid19 crisis. | |

| PHYK3 | In our organisation, the critical infrastructure is sufficient to overcome this crisis. | |

| PHYK4 | I am confident that my organisation can adopt to changed business environment post Covid19 crisis. | |

| CSR-Environment/Community | ||

|---|---|---|

| CSRENV1 | My hotel incorporates environmental concerns in business decisions | Park and Levy (2014) |

| CSRENV2 | My hotel actively attempts to minimize the environmental impact of the hotel’s activities | |

| CSRENV3 | My hotel encourages guests to reduce their environmental impact through programs and initiatives | |

| CSRENV4 | My hotel incorporates the interests of community in business decisions | |

| CSRENV5 | My hotel helps improve the quality of life in the local community | |

| CSR-Employees | ||

|---|---|---|

| CSREMP1 | My hotel treats our employees fairly and respectfully | Park and Levy (2014) |

| CSREMP2 | My hotel provides employees with fair and reasonable salaries | |

| CSREMP3 | My hotel’s policies encourage a good work and life balance for employees | |

| CSREMP4 | My hotel provides a safe and healthy working environment to all employees | |

| Organizational Resilience | ||

|---|---|---|

| Organisational resilience-Adaptive capacity | ||

| ADAP1 | Management in this hotel listens actively to the problems in our organization | Lee et al. (2013) |

| ADAP2 | There is a good work ambience and team work spirit | |

| ADAP3 | The organization actively encourages employees to develop themselves through their work. | |

| ADAP4 | People in the organization work across the departments if necessary to do things well | |

| ADAP5 | I am positive that leadership in this organization is good for times of crisis | |

| ADAP6 | The organization has learnt from past experiences and will use the knowledge to overcome this crisis | |

| Organisational resilience-Planning | ||

| PLAN1 | I believe that our organization’s priorities for recovery from a crisis would be sufficient to provide direction for staff | Lee et al. (2013) |

| PLAN2 | Our organization has clearly defined priorities for what is important during and after a crisis | |

| PLAN3 | Our organization has thought about and planned for support that it could provide to the community during the crisis. | |

| PLAN4 | Given our level of importance to our stakeholders I believe that the way we plan for crisis is appropriate. | |

| Organisational response to COVID-19 (Current Actions) | ||

|---|---|---|

| CURR1 | Financial / economic assistance has been offered to employees to compensate for possible liquidity losses during the temporary lay-offs of staff | Own elaboration based on interviews |

| CURR2 | Employees have been offered the opportunity to perform some more sporadic / temporary jobs | |

| CURR3 | 100% of bookings cancelled by customers as a result of the crisis have been reimbursed | |

| CURR4 | Holydays vouchers have been offered to customers to compensate them for reservations already paid that they will not be able to enjoy | |

| CURR5 | The hotel facilities have been used as hospitals or places to welcome employees from the health sector | |

| CURR6 | Food surpluses have been donated (to employees or NGOs) due to the closure of the establishment | |

| Organisational response to COVID-19 (Future Actions) | ||

|---|---|---|

| FUT1 | The layout of the hotel spaces (lobby, common areas, restaurant …) will be modified to guarantee the social distance between people | Own elaboration based on interviews |

| FUT2 | Clients' health will be monitored regularly during their stay at the hotel | |

| FUT3 | New cleaning and disinfection protocols will be implemented | |

| FUT4 | New food preparation and serving protocols will be implemented | |

| FUT5 | More active measures for the use of contactless digital technologies (digital keys, digital payment, mobile payment, digital interactions, etc.) will be launched. | |

| Perceived job security | ||

|---|---|---|

| SECUR1 | When Covid19 crisis is over, my job will be secure | Mohsin et al. (2013) |

| SECUR2 | When Covid19 crisis is over, I will continue receiving my salary | |

| SECUR3 | When Covid19 crisis is over, I will work adequate hours | |

| SECUR4 | When Covid19 crisis is over, the job benefits available to me will remain the same | |

| Organisational commitment | ||

|---|---|---|

| Affective Commitment | ||

| AFF1 | I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organisation | |

| AFF2 | I feel a strong sense of belonging to my organisation | |

| AFF3 | I feel emotionally attached to this organisation | |

| AFF4 | I feel like part of the family at my organisation | Lee et al. (2001) |

| Normative Commitment | ||

| NOR1 | I would feel guilty if I left this organisation now | |

| NOR2 | Even if it were to my advantage, I do not feel it would be right to leave my organisation now | |

| NOR3 | This organisation deserves my loyalty | |

References

- Aguirre-Urreta M.I., Rönkkö M. Statistical inference with PLSc using bootstrap confidence intervals. MIS Q. 2018;42(3):1001–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Baum T., Hai N.T.T. Hospitality, tourism, human rights and the impact of COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2020;32(7):2397–2407. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs D., Hall C.M., Stoeckl N. The resilience of formal and informal tourism enterprises to disasters: reef tourism in Phuket, Thailand. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012;20(5):645–665. [Google Scholar]

- Birdir K. General manager turnover and root causes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2002;14(1):43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Brown N.A., Rovins J.E., Feldmann-Jensen S., Orchiston C., Johnston D. Exploring disaster resilience within the hotel sector: a systematic review of literature. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017;22:362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N.A., Orchiston C., Rovins J.E., Feldmann-Jensen S., Johnston D. An integrative framework for investigating disaster resilience within the hotel sector. J. Hosp. Tour. Manage. 2018;36:67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Brown N.A., Rovins J.E., Feldmann-Jensen S., Orchiston C., Johnston D. Measuring disaster resilience within the hotel sector: an exploratory survey of Wellington and Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand hotel staff and managers. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019;33:108–121. [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale J.B., Hatak I. Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: implications for human resource management. J. Bus. Res. 2020;116:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalan News . Catalan News; 2020. A Look inside Hotel Hesperia, Converted into Emergency Hospital in Four Days. 03 April 2020. Available from: https://www.catalannews.com/society-science/item/a-look-inside-hotel-hesperia-converted-into-emergency-hospital-in-four-days [Accessed 13 June 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda-Carrion G., Cegarra-Navarro J.-G., Cillo V. Tips to use partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) in knowledge management. J. Knowl. Manage. 2019;23(1):67–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung C., Law R., He K. Essential hotel managerial competencies for graduate students. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2010;22(4):25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra T.K., Henseler J. Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Q. 2015;39(2):297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Dobie S., Schneider J., Kesgin M., Lagiewski R. Hotels as critical hubs for destination disaster resilience: an analysis of hotel corporations’ CSR activities supporting disaster relief and resilience. Infrastructures. 2018;3(4):46. [Google Scholar]

- Dube K., Nhamo G., Chikodzi D. COVID-19 cripples global restaurant and hospitality industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020 doi: 10.1080/13683500.2020.1773416. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers F. Masters of disasters? Challenges and opportunities for SMEs in times of crisis. J. Bus. Res. 2020;116:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger A., Grabner-Krauter S., Terlutter R. Online CSR communication in the hotel industry: evidence from small hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manage. 2018;68:94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Filimonau V., Corradini S. Zero-hours contracts and their perceived impact on job motivation of event catering staff. Event Manage. 2019 doi: 10.3727/152599519X15506259855869. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Filimonau V., De Coteau D. Tourism resilience in the context of integrated destination and disaster management (DM2) Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020;22(2):202–222. [Google Scholar]

- Filimonau V., Magklaropoulou A. Exploring the viability of a new ‘pay-as-you-use’ energy management model in budget hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manage. 2020;89 [Google Scholar]

- Filimonau V., Matute J., Kubal-Czerwinska M., Krzesiwo K., Mika M. The determinants of consumer engagement in restaurant food waste mitigation in Poland: an exploratory study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;247 [Google Scholar]

- Giudici M., Filimonau V. Exploring the linkages between managerial leadership, communication and teamwork in successful event delivery. Tourism Manage. Perspect. 2019;32 [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Diaz B., Gomez M., Molina A. Configuration of the hotel and non-hotel accommodations: an empirical approach using network analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manage. 2015;48:39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling S., Scott D., Hall C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020 doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Hult G.T.M., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 2017. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Risher J.J., Sarstedt M., Ringle C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019;31(1):2–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hall C.M., Prayag G., Amore A. Channel View Publications; Bristol: 2018. Tourism and Resilience: Individual, Organisational and Destination Perspectives. [Google Scholar]

- Hall C.M., Scott D., Gössling S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tour. Geogr. 2020 doi: 10.1080/14616688.2020.1759131. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock A. Restaurants, hotels and gyms face up to a future of social distancing. Financ. Times. 2020;(22 April 2020) Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/7c902798-4d90-4206-9fd4-bafa154ef1e1 [Accessed 13 June 2020] [Google Scholar]

- He H., Harris L. The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. J. Bus. Res. 2020;116:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healing Manor Hotel . 2020. COVID-19 Take Away Menu. Available from: h ttps://www.healingmanorhotel.co.uk/food-drink/covid-19-take-away-menu/ [Accessed 13 June 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J.C. Corporate social responsibility and tourism: hotel companies in Phuket, Thailand, after the Indian Ocean tsunami. Int. J. Hosp. Manage. 2007;26(1):228–239. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J. Partial least squares path modeling: Quo vadis? Qual. Quant. 2018;52(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11135-016-0401-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015;43(1):115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J., Hubona G., Ray P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016;116(1):2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hodari D., Sturman M.C. Who’s in charge now? The decision autonomy of hotel general managers. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014;55(4):433–447. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Wen J. Effects of COVID-19 on hotel marketing and management: a perspective article. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2020 doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-03-2020-0237. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Ritchie B.W., Verreynne M.-L. Building tourism organisational resilience to crises and disasters: a dynamic capabilities view. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019;21(6):882–900. [Google Scholar]

- Kichuk A., Brown L., Ladkin A. Talent pool exclusion: the hotel employee perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2019;31(10):3970–3991. [Google Scholar]