Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: Crystal arthritis, diabetes, allopurinol

Abstract

To assess the impact of allopurinol on diabetes in a retrospective cohort of Veterans’ Affairs patients with gout.

The New York Harbor VA computerized patient record system was searched to identify patients with an ICD-9 code for gout meeting at least 4 modified 1977 American Rheumatology Association gout diagnostic criteria. Patients were divided into subgroups based on >30 continuous days of allopurinol, versus no allopurinol. New diagnoses of diabetes, defined according to American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria or clinical documentation explicitly stating a new diagnosis of diabetes, were identified during an observation period from January 1, 2000 through December 31, 2015.

Six hundred six gout patients used allopurinol >30 continuous days, and 478 patients never used allopurinol. Over an average 7.9 ± 4.8 years of follow-up, there was no significant difference in diabetes incidence between the allopurinol and non-allopurinol groups (11.7/1000 person-years vs 10.0/1000 person-years, P = .27). A lower diabetes incidence in the longest versus shortest quartiles of allopurinol use (6.3 per 1000 person-years vs 19.4 per 1000 person-years, P<.0001) was attributable to longer duration of medical follow-up.

In this study, allopurinol use was not associated with decreased diabetes incidence. Prospective studies may further elucidate the relationship between hyperuricemia, gout, xanthine oxidase activity, and diabetes, and the potential impact of gout treatments on diabetes incidence.

1. Introduction

Several studies suggest that patients with gout are at increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes.[1–4] Although the basis for this risk is not known, possible explanations include increased systemic inflammation that may impair insulin sensitivity, as well as urate-related inhibition of the enzyme AMP kinase, which may play a central role in the effects of high-fructose diets on both gout and diabetes.[5] Hyperuricemia may also be a risk factor for the development of hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance.[6] Alternatively, recent studies suggest that increased activity of xanthine oxidase (the enzyme that generates uric acid), independent of serum urate level, may be associated with the development of hyperinsulinemia and type 2 diabetes.[7,8]

Despite the evidence that xanthine oxidase activity and/or hyperuricemia may be associated with diabetes risk, studies of xanthine oxidase inhibitor use in diabetes have yielded mixed results. One brief trial randomized 73 patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia and no diabetes to receive either allopurinol 300 mg daily or placebo. After 3 months of treatment, patients in the allopurinol group had significantly improved fasting blood glucose, fasting insulin, Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) levels compared to patients in the hyperuricemic placebo group.[9] In an observational study of a cohort of patients followed prospectively for 4 years, patients who used allopurinol and had improved serum urate levels had significantly improved plasma fasting blood glucose levels. However, patients who experienced spontaneously improved serum urate levels without the use of allopurinol did not experience a significant change in their plasma fasting blood glucose levels, suggesting that the allopurinol effect may not have been linked directly to serum urate lowering.[10] In contrast, a study of 41 patients with diabetes, randomized to receive allopurinol 100 mg or placebo 3 times daily for 14 days, demonstrated no significant reduction in fasting blood glucose or hemoglobin A1c levels in either group.[11] Furthermore, a study utilizing Taiwan's national health insurance research database found a direct and dose-dependent relationship between allopurinol use and diabetes risk.[12]

In the present study, we aimed to clarify the association between allopurinol use and diabetes incidence by conducting a retrospective cohort study in a well-characterized population of patients with gout who had received care at the New York Harbor VA Health Care System of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (NYH VA).

2. Methods

We utilized a previously established database of subjects with gout, which was collected starting in 2008, and extended it for 5 additional years.[13] For this dataset, we identified all patients with an International Classification of Diseases, 9th ed. (ICD-9) code for gout (274.xx) and at least 1 visit documented in the NYH VA computerized patient record system (CPRS) between August 1, 2007 and August 1, 2008. Each patient's record was manually reviewed to confirm a diagnosis of gout according to the 1977 American Rheumatism Association (ARA) classification criteria (with the use of urate lowering therapy accepted as a surrogate for hyperuricemia).[14] Patients’ clinical notes, vital signs, and laboratory results were reviewed to identify demographics, comorbidities, and the use of steroids and statins. Patients who carried a diagnosis of diabetes at baseline were excluded from the study.

The study period was defined as January 1, 2000 through December 31, 2015. Patients were divided into groups based on whether or not they used allopurinol during the study period. Patients were included in the allopurinol use group if they filled at least 2 or more consecutive prescriptions totaling >30-days for allopurinol. We chose this threshold to confirm the intent of the treating physician to place the patient on chronic allopurinol therapy, to confirm at least a minimal commitment to patient compliance, and to ensure at least a minimal treatment period. Patients were assigned to the control group if they had never received an allopurinol prescription during the study period. Patients who filled prescriptions for allopurinol for 30 days or fewer during the study period were excluded. Allopurinol and colchicine use information, including dosing and dates of initial prescription and refills, were obtained from the NYH VA electronic pharmacy records. For each patient in the allopurinol group, the index date of observation was defined as the date of the earliest allopurinol prescription within the study period. For each patient in the non-allopurinol group, the index date was defined as the later of either the date of gout diagnosis or January 1, 2000.

The primary outcome of the study was the incidence of new type 2 diabetes diagnoses in each group. Incident diabetes was defined either as meeting 1 criterion from the American Diabetes Association's definition of diabetes (a hemoglobin A1c that was newly ≥ 6.5%, a fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL, an oral glucose tolerance test 2 hour blood glucose ≥200 mg/dL, or a random blood glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL in the setting of hyperglycemic symptoms); or physicians’ notes within the study period explicitly stating that the subject had a new diagnosis of diabetes. In the case of physician diagnosis, charts were reviewed for corroborating data, and patients lacking corroborating data (e.g., subsequently meeting ADA criteria, treatment with glucose lowering agents, or explicit documentation of disease, and management plan) were excluded. Patients were also excluded if chart review indicated evidence that their diabetes could possibly be of a type other than type 2 (e.g., alcoholic, viral, or malignant pancreas damage, evidence of diabetic ketoacidosis, or explicit physician documentation of a non-type 2 diabetes). We hypothesized that gout patients taking allopurinol would experience a lower incidence of type 2 diabetes than those not taking allopurinol.

Student t test (continuous variables) and Fisher exact test (categorical variables) were used to compare baseline characteristics. Categorical outcome variables, including the primary endpoint, were analyzed utilizing Fisher exact test. Continuous outcome variables were analyzed using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. Multivariate analysis was performed using R software version 3.6.1. The remainder of the statistical analysis was performed using Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp, LLC. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the New York Harbor Veterans’ Affairs Healthcare System, approval number 01700. Informed consent for each individual patient was waived for this study as this was a retrospective analysis of data which was collected for the purposes of clinical care.

3. Results

3.1. Patients and demographics

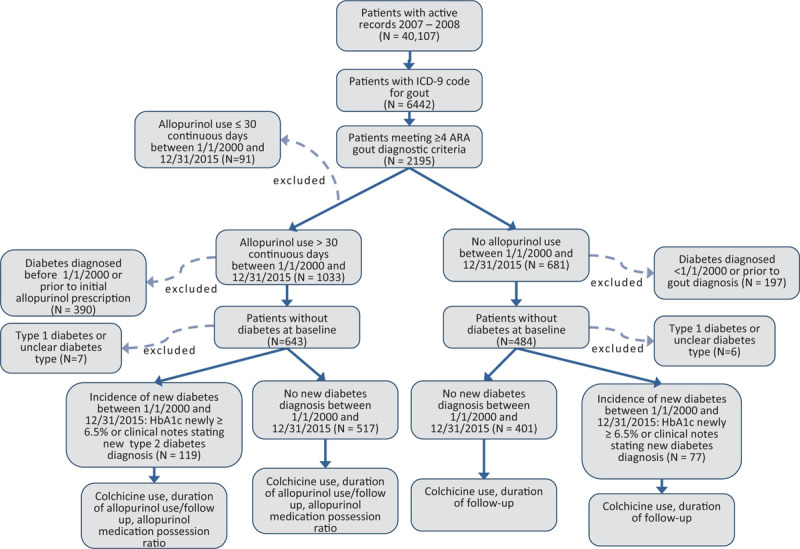

40,107 patients had at least 1 documented clinical visit within the NYH VA CPRS between August 1, 2007 and August 1, 2008. From among these patients, 6442 had an ICD-9 code for gout, and 2195 of those patients met at least 4 of the 1977 ARA gout classification criteria. Of these, 587 patients were excluded for diabetes at baseline, and 91 additional patients were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criterion for allopurinol use during the study period. After applying exclusion criteria, 636 patients were included in the allopurinol group, and 478 patients were included in the non-allopurinol group (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart depicting patient selection and analysis.

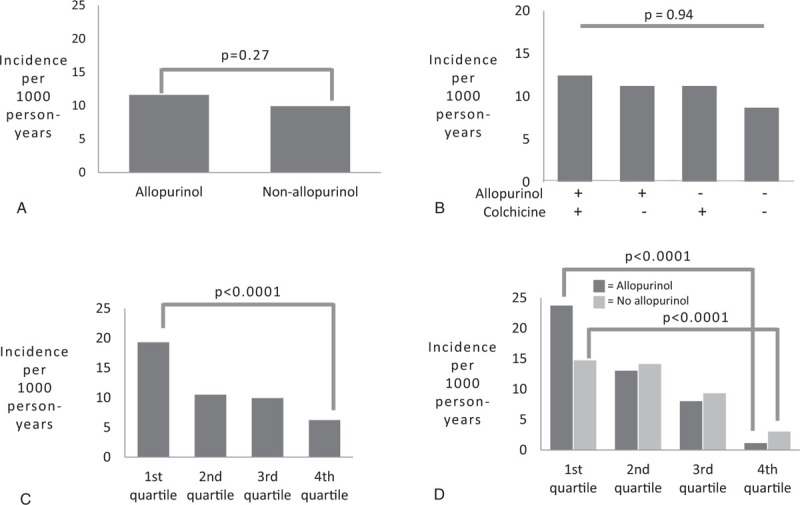

Table 1 compares the baseline demographic information, comorbidities, use of statins, steroids, and/or colchicine between the allopurinol and non-allopurinol groups, collected at the study index date for each patient. Patients in the allopurinol group were more likely to be black, less likely to have used statins during the study period, and more likely to have used steroids and/or colchicine during the study period. Patients in the allopurinol group were also less likely to have chronic kidney disease (CKD), presumably because of concerns about using allopurinol in patients with CKD prior to the publication of the American College of Rheumatology 2012 Gout Treatment Guidelines.[15,16] Supplementary Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the excluded patients.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic information, co-morbidities, and medication use of the study sample.

3.2. Overall diabetes incidence

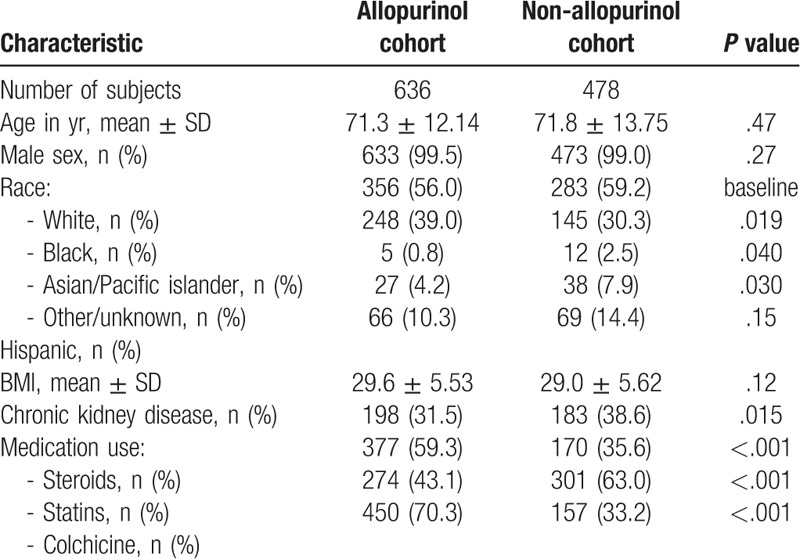

One hundred sixty-six patients were diagnosed with incident diabetes based on elevated hemoglobin A1c levels or elevated fasting blood glucose, while 41 patients were diagnosed with incident diabetes based on physician diagnosis with corroborating data support. Four patients (2 taking and 2 not taking allopurinol) with a physician diagnosis of incident diabetes who were lacking corroborating data were excluded from further analysis. Twenty patients in the allopurinol group were diagnosed with incident diabetes by physician diagnosis, compared to 21 patients in the non-allopurinol group (P = .43). Among patients in the allopurinol group, we observed no significant difference in incidence of type 2 diabetes compared to the non-allopurinol group, over an average 7.9 ± 4.8 years of follow-up (11.7 per 1000 person-years in allopurinol group compared to 10.0 per 1000 person-years in the non-allopurinol group, P = .27) (Fig. 2A). Among patients on allopurinol who experienced a new diagnosis of type 2 diabetes during the observation period, the mean duration of allopurinol use prior to diabetes diagnosis was 4.0 ± 3.50 years and the mean allopurinol dose was 211.9 ± 90.6 mg daily. The mean duration of observation prior to diabetes diagnosis in control patients was 4.17 ± 3.6 years (P = .76).

Figure 2.

(A) Overall incidence of type 2 diabetes among patients in the allopurinol and non-allopurinol groups during study period, (B) Diabetes incidence among patients who were prescribed both allopurinol and colchicine, only allopurinol, only colchicine, and neither medication during the study period, (C) Diabetes incidence for each quartile of duration of allopurinol use among patients in the allopurinol group, (D) Diabetes incidence for each quartile of duration of observation among all patients. ∗ANOVA analysis across all categories.

3.3. Colchicine use

Previous studies have suggested that colchicine acts on pathways common to gout and diabetes, including the interleukin-1β/cryopyrin and AMP kinase pathways.[5,17,18] To evaluate for a possible confounding colchicine effect on diabetes incidence, patients were categorized into 4 groups:

-

1)

those who used both allopurinol and colchicine for >30 days during the study period (N = 448);

-

2)

those who used only allopurinol (N = 140);

-

3)

those who used only colchicine (N = 157), and

-

4)

those who used neither allopurinol nor colchicine (N = 271). No significant difference in diabetes incidence was found between these 4 groups (Fig. 2B).

3.4. Duration of allopurinol use

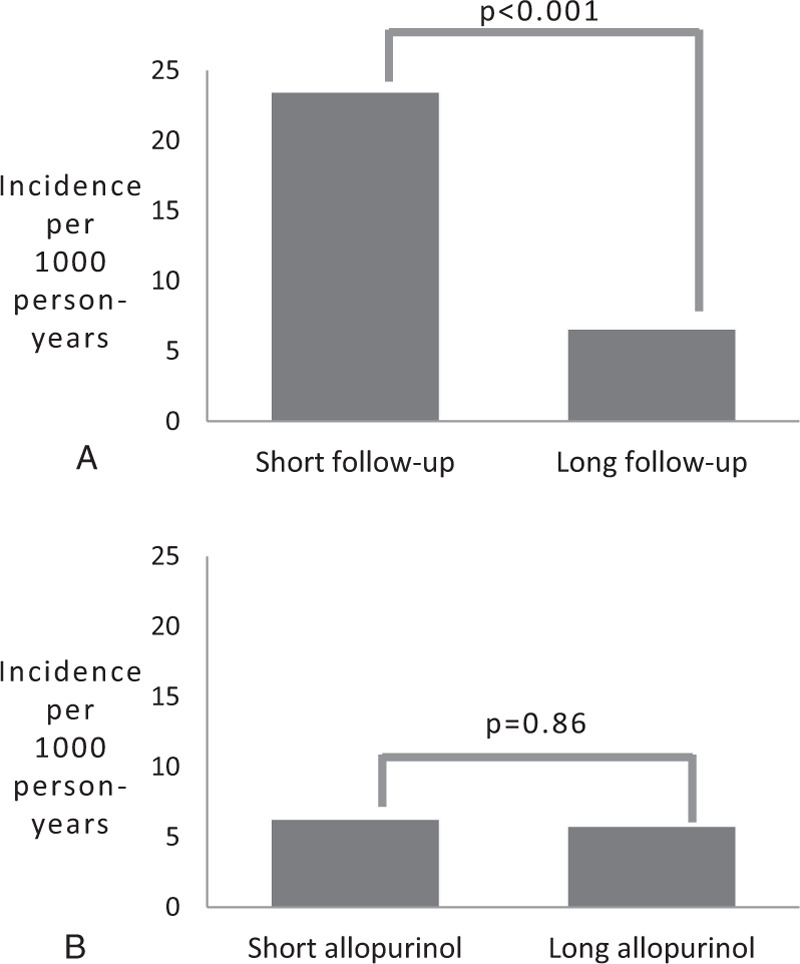

The mean duration of allopurinol use was 3.62 ± 3.33 years. The mean duration of observation was 9.17 ± 4.62 years for the allopurinol group and 6.69 ± 4.31 years for the control group (P = <.00001). To assess whether duration of allopurinol use affected diabetes incidence, patients in the allopurinol group were divided into quartiles based on the total number of months of use during the study period. Patients in the longest quartile of allopurinol use had a significantly lower incidence rate of type 2 diabetes than those in the shortest quartile of use (6.3 per 1000 person-years vs 19.4 per 1000 person-years, P<.0001) (Fig. 2C). However, when patients in the allopurinol group were divided into quartiles based on duration of observation rather than allopurinol treatment, we observed a similar difference in diabetes incidence rate between patients in the longest quartile of observation and those in the shortest quartile (3.3 per 1000 person-years vs 15.2 per 1000 person-years, P<.0001) (Fig. 2D). Moreover, when patients in the non-allopurinol group were divided into quartiles based on duration of observation, we saw a similar reduction in diabetes incidence rate with longer observation. To further assess for the possibility that the duration of follow-up might be influencing diabetes incidence, patients in the shortest 2 quartiles of allopurinol treatment duration were divided into those patients who had short observation periods (defined as less than the mean 7.9 years duration of follow-up, n = 68) and those who had long observation periods (defined as ≥ 8 years, n = 252). Diabetes incidence rate was found to be significantly higher for the short observation group compared to the long observation group, (23.5 per 1000 person-years compared to 6.6 per 1000 person-years, P < .001), despite similar durations of allopurinol treatment (Fig. 3A). Conversely, when patients with a long duration of observation (defined as ≥ 8 years) were divided into those with a short duration of allopurinol exposure (lowest 2 quartiles, n = 233) and long duration of allopurinol exposure (highest 2 quartiles, n = 140), no significant difference in diabetes incidences was found between the short allopurinol group and the long allopurinol group (6.3 per 1000 person-years compared to 5.8 per 1000 person-years, P = .86) (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that longer duration of allopurinol treatment was not responsible for the lower incidence rate of diabetes observed in the long observation group.

Figure 3.

(A) Diabetes incidence among patients in the lowest 2 quartiles of allopurinol use, stratified by duration of observation, (B) Diabetes incidence among patients with a long duration of follow-up, stratified by duration of allopurinol use.

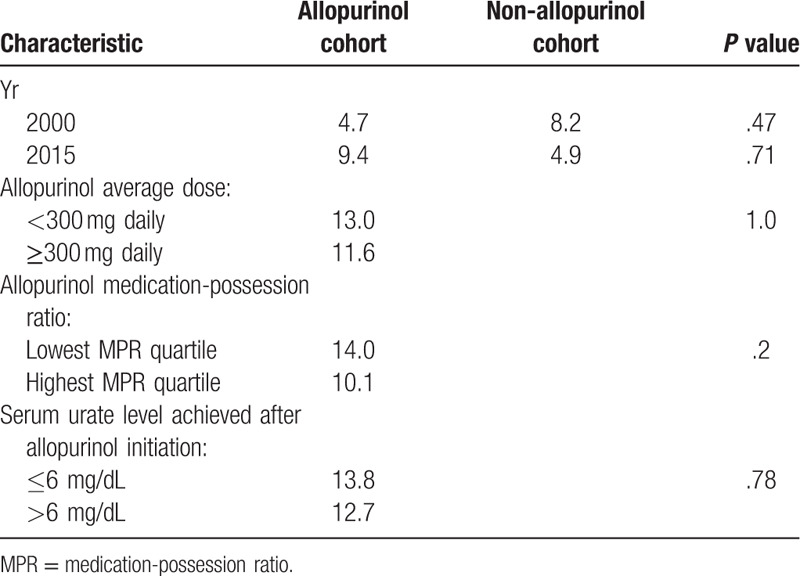

Given the possibility that new therapies and/or practice guidelines may have affected diabetes incidence over the 16-year course of our study period, we calculated the diabetes incidence of patients in the allopurinol and non-allopurinol groups by calendar year. No trend in diabetes incidence was found when comparing the years 2000 and 2015 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Diabetes incidence among patients taking allopurinol and those not taking allopurinol, stratified by calendar year of diabetes diagnosis, allopurinol dose, allopurinol adherence and serum urate levels.

3.5. Allopurinol dose

To assess for dose effect, diabetes incidence was also compared between patients on higher doses of allopurinol (average dose ≥300 mg daily) and those who received no allopurinol during the study period. There was no significant difference in diabetes incidence between patients on high doses of allopurinol and those on no allopurinol (11.6 per 1000 person-years in high allopurinol group vs 10.0 per 1000 person-years in non-allopurinol group, P = .42). There was also no significant difference in diabetes incidence between patients on high doses of allopurinol and low doses (<300 mg) of allopurinol (incidence was 13.0 per 1000 person-years for low allopurinol dose; P = 1.0) (Table 2).

3.6. Allopurinol adherence

To account for non-adherence among patients in the allopurinol group, diabetes incidence was stratified by quartiles of medication possession ratio (MPR). There was no significant difference in diabetes incidence between the highest and lowest MPR quartiles (10.1 per 1000 person-years for the highest quartile compared with 14.0 per 1000 person-years for the lowest quartile, P = .20) (Table 2).

3.7. Serum urate

To evaluate for a possible effect of serum urate concentration on diabetes development, diabetes incidence was calculated according to baseline serum urate level, as well as by extent of serum urate change over the first 6 to 12 months of observation, regardless of allopurinol use status. There was no association between either baseline serum urate level (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.87–1.06) or extent of serum urate change (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.93–1.2) and diabetes incidence.

Diabetes incidence was further assessed according to extent of serum urate change 6 to 12 months after allopurinol initiation, for patients in the allopurinol group. There was no association between extent of serum urate change and diabetes incidence in this group (OR 1.07, 95% CI 0.94–1.22). Additionally, we assessed whether achieving the recommended target serum urate level for most patients with gout (defined as ≤6 mg/dL) was related to reduced diabetes incidence.[15] Patients with available follow-up serum urate levels were divided into those who achieved the target serum urate level 6 to 12 months after allopurinol initiation (N = 119), and those who did not (N = 217). There was no significant difference in diabetes incidence between these 2 groups (13.8 per 1000 person-years in the achieved target urate group vs 12.7 per 1000 person-years in those who did not achieve target urate level, P = .78) (Table 2).

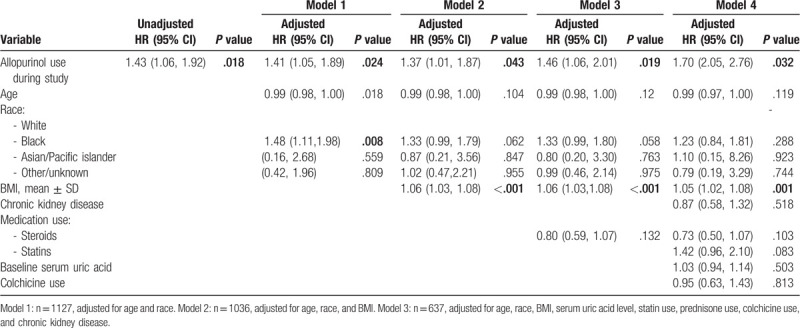

3.8. Multivariate analysis

Diabetes incidence during the study period was analyzed in multivariate logistic and Cox regressions including allopurinol use, baseline age, race, BMI, CKD, baseline serum uric acid, statin use, prednisone use, and colchicine use. The multivariate logistic regression demonstrated no significant association between allopurinol use and diabetes incidence. However, the Cox proportional hazards model demonstrated a significantly increased hazard ratio for diabetes incidence among subjects taking allopurinol compared to subjects who did not take allopurinol (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cox multivariate regression analysis of potential risk factors among patients diagnosed with diabetes.

3.9. Gout diagnosed during study period

Patients with gout whose index date was January 1, 2000, (first date of observation period) had gout diagnoses of indeterminate time prior to that date, setting up a possible chronological bias in the study design. To address this issue, a subset of patients who were unequivocally diagnosed with gout after January 1, 2000 based on electronic medical records was selected from the total sample (N = 333), and diabetes incidence was compared in patients who used allopurinol within that group (N = 156), versus those who did not (N = 177). Supplementary Table 2, compares the baseline demographic information between the allopurinol and non-allopurinol groups within this subset. Patients in this subanalysis were similar in most respects, except that the patients who had taken allopurinol were less likely to be Hispanic, and more likely to have taken steroids, compared with the non-allopurinol group. No difference in diabetes incidence was found between the 2 groups (9.2 per 1000 person-years in both groups). In addition, there was no significant difference in the average time from gout diagnosis to new diabetes diagnosis between patients who used allopurinol and those who did not (53.9 months ± 40.93 vs 51.0 months ± 38.9, P = .78). As for the entire cohort, a decreased incidence rate of diabetes with longer allopurinol treatment was likely confounded by duration of observation (Supplementary Fig. 1).

4. Discussion

Based on several biological and clinical observations, recent studies suggest that allopurinol use may be associated with improved insulin sensitivity and blood glucose levels. There is evidence that decreased urate may account for some of this benefit, but suppression of xanthine oxidase activity may also play a role. Xanthine oxidase activity has been linked to increased reactive oxygen species generation in the setting of hyperglycemia, and allopurinol has been found to prevent this effect.[19] Nevertheless, our study did not demonstrate an association between allopurinol use and decreased diabetes incidence among patients with gout. Diabetes incidence did decline with longer duration of allopurinol use, but this effect appeared to be related to duration of observation rather than to duration of allopurinol itself. On the other hand, we noted a significant increase in the hazard ratio for diabetes among subjects taking allopurinol in the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, results which contrasted with the rest of the findings of the study, and which are not explained by the analyses of comorbidities, medication use, and duration of follow-up that we performed. It is possible that other factors associated with allopurinol use were not captured by the data collected for this study, and contributed to the increased hazard ratio.

This study also found no association between colchicine use and diabetes incidence, in spite of evidence suggesting that colchicine acts on several pathophysiologic mechanisms involved in diabetes. A recent study of more than 27,000 Veterans’ Affairs patients with gout also found no overall association between colchicine use and risk of diabetes, although there was a trend toward decreased incidence with increased doses and duration of colchicine use.[20] Since we did not analyze diabetes incidence by colchicine dose in our study, we are unable to comment on whether using higher doses of colchicine may be associated with reduced diabetes incidence.

Our study had several strengths. The sample size was large, and patients were followed for a long duration of time. We rigorously defined gout and confirmed the diagnosis with direct chart review for each subject. The majority of patients with new-onset diabetes had documented hemoglobin A1c levels ≥ 6.5%, an objective and widely accepted measure of diabetes. The study also utilized allopurinol use data collected in a real-world healthcare setting, and was thus likely reflective of patients’ everyday patterns of allopurinol use. Indeed, our ability to individually review the patient's records during initial data collection rendered our study relatively protected from errors of coding.

There are several important limitations to this study. Our use of 1977 ARA criteria for gout, instead of the more recent 2015 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria, was predicated on the fact that data collection for this data set was begun before 2015.[21] However, our use of ICD-9 diagnosis as an entry criterion before applying ARA criteria ensured that our ascertainment of gout was at least 95% specific.[22] Given the retrospective nature of our design, it is likely that we were unable to capture all of the allopurinol use for all of the patients. Similarly, it is impossible for us to fully assess adherence to allopurinol therapy, although we approached this issue through several sub-analyses. The fact that allopurinol use was shorter than the observational period for allopurinol users indicates that allopurinol use was intermittent for many patients, consistent with prior reports; whether continuous allopurinol use would have a greater impact on diabetes incidence cannot be determined.[23,24] We were not able to assess the impact of other urate-lowering therapies, since their use was either negligible or not available at the initiation of the study. Additionally, although we utilized all 4 of the 2018 American Diabetes Association criteria (along with physician notation of new diabetes) to diagnose diabetes in our cohort, only hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5% was commonly observed.[25] Therefore, it is possible that we did not capture all of the incident diabetes cases for our sample. It is also possible that some of the patients characterized as having new diabetes in our study may have had diabetes at baseline, which was either not documented properly or was not properly evaluated in a medical setting until a date within our study period. Patients on allopurinol were more likely to have received steroids, which could have contributed to increased diabetes incidence and obscured any beneficial effect of urate lowering.

5. Conclusion

This study found that allopurinol use was not associated with decreased incidence of type 2 diabetes among patients with gout. No association with diabetes incidence was found when allopurinol use was stratified by dose or by measures of adherence to allopurinol therapy. Diabetes incidence was not associated with baseline serum urate or change in serum urate level. Colchicine use was also not associated with diabetes incidence. Whether allopurinol use could reduce diabetes incidence in a more narrowly defined subset of patients, or in patients with hyperuricemia without gout, remains to be determined, most likely through prospective trials.

Author contributions

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ACR = American College of Rheumatology, AMP kinase = 5’ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase, ARA = American Rheumatism Association, CPRS = computerized patient record system, HOMA-IR = homeostatic model of insulin resistance, hsCRP = high-sensitivity c-reactive protein, ICD-9 = international classification of diseases, 9th ed., MPR = medication possession ratio, NYH VA = New York Harbor Veterans’ Affairs Healthcare System.

How to cite this article: Slobodnick A, Toprover M, Greenberg J, Crittenden DB, Pike VC, Qian Y, Zhong H, Pillinger MH. Allopurinol use and type 2 diabetes incidence among patients with gout: a VA retrospective cohort study. Medicine. 2020;99:35(e21675).

JG is currently the Chief Scientific Officer for CORRONA. DBC is currently employed by Terns Pharmaceuticals. MHP is supported in part by NYU CTSA grant 1UL1TR001445 from the National Center for the Advancement of Translational Science (NCATS). NIH has served as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Crealta/Horizon and Sobi, and has received investigator-initiated grant funding from Hikma and Horizon Therapeutics.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- [1].Kim SC, Liu J, Solomon DH. Risk of incident diabetes in patients with gout: a cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:273–80.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Choi HK, De Vera MA, Krishnan E. Gout and the risk of type 2 diabetes among men with a high cardiovascular risk profile. Rheumatology 2008;47:1567–70.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tung Y-C, Lee S-S, Tsai W-C, et al. Association between gout and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Med 2016;129:1219e17–25.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Pan A, Teng GG, Yuan J-M, et al. Bidirectional association between diabetes and gout: the Singapore Chinese health study. Sci Rep 2016;6:25766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Thottam GE, Krasnokutsky S, Pillinger MH. Gout and metabolic syndrome: a tangled web. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2017;19:60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Niskanen L, Laaksonen DE, Lindstrom J, et al. Serum uric acid as a harbinger of metabolic outcome in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance: the Finnish diabetes prevention study. Diabetes Care 2006;29:709–11.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Li X, Meng X, Gao X, et al. Elevated serum xanthine oxidase activity is associated with the development of type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 2018;41:884–90.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sunagawa S, Shirakura T, Hokama N, et al. Activity of xanthine oxidase in plasma correlates with indices of insulin resistance and liver dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome: a pilot exploratory study. J Diabetes Investig 2019;10:94–103.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Takir M, Kostek O, Ozkok A, et al. Lowering uric acid with allopurinol improves insulin resistance and systemic inflammation in asymptomatic hyperuricemia. J Investig Med 2015;63:924–9.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cicero AFG, Rosticci M, Bove M, et al. Serum uric acid change and modification of blood pressure and fasting plasma glucose in an overall healthy population sample: data from the Brisighella heart study. Ann Med 2017;49:275–82.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Afshari M, Larijani B, Rezaie A, et al. Ineffectiveness of allopurinol in reduction of oxidative stress in diabetic patients; a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Biomed Pharmacother 2004;58:546–50.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chang H-W, Lin Y-W, Lin M-H, et al. Associations between urate-lowering therapy and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Shimosawa T, ed. PLoS One 2019;14:e0210085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Crittenden DB, Lehmann RA, Schneck L, et al. Colchicine use is associated with decreased prevalence of myocardial infarction in patients with gout. J Rheumatol 2012;39:1458–64.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, et al. Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum 1977;20:895–900.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and antiinflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:1447–61.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Toprover M, Crittenden DB, Modjinou DV, et al. Low-dose allopurinol promotes greater serum urate lowering in gout patients with chronic kidney disease compared with normal kidney function. Bull Hosp Jt Dis 2019;77:87–91.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang Y, Viollet B, Terkeltaub R, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase suppresses urate crystal-induced inflammation and transduces colchicine effects in macrophages. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:286–94.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ehses JA, Lacraz G, Giroix M-H, et al. IL-1 antagonism reduces hyperglycemia and tissue inflammation in the type 2 diabetic GK rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2009;106:13998–4003.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Eleftheriadis T, Pissas G, Antoniadi G, et al. Allopurinol protects human glomerular endothelial cells from high glucose-induced reactive oxygen species generation, p53 overexpression and endothelial dysfunction. Int Urol Nephrol 2018;50:179–86.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang L, Sawhney M, Zhao Y, et al. Association between colchicine and risk of diabetes among the veterans affairs population with gout. Clin Ther 2015;37:1206–15.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Neogi T, Jansen TLTA, Dalbeth N, et al. 2015 gout classification criteria: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1789–98.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Singh JA. Veterans affairs databases are accurate for gout-related health care utilization: a validation study. Arthritis Res Ther 2013;15:R224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mantarro S, Capogrosso-Sansone A, Tuccori M, et al. Allopurinol adherence among patients with gout: an Italian general practice database study. Int J Clin Pract 2015;69:757–65.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Riedel AA, Nelson M, Joseph-Ridge N, et al. Compliance with allopurinol therapy among managed care enrollees with gout: a retrospective analysis of administrative claims. J Rheumatol 2004;31:1575–81.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care 2018;41: Suppl 1: S13–27.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.