Graphical abstract

Keywords: Artificial infection, Host resistance, Morada Nova breed, Resilience, Sheep haemonchosis

Highlights

-

•

Resistance against Haemonchus contortus was assessed in a Morada Nova flock.

-

•

More than 88% of the lambs had PCV ≥ 24% even with high fecal egg counts (FEC).

-

•

Only susceptible lambs had decreased live weight due to parasitism.

-

•

More than 98% of the ewes had FEC below 4000 EPG.

-

•

PCV of the ewes was not affected by H. contortus infection.

Abstract

Morada Nova is a Brazilian hair sheep breed that is well adapted to the country’s mainly tropical climate and has good potential for meat and leather production. This breed is reported to be resistant to Haemonchus contortus infection, a highly desired characteristic due to the large impact of this parasite on sheep farming. Therefore, the present study aimed to characterize 287 recently weaned Morada Nova lambs and 123 ewes in relation to their resistance against H. contortus. The animals were dewormed and 15 days later artificially infected with 4000 H. contortus L3 (D0). They were individually monitored by periodic assessment of fecal egg count (FEC), packed cell volume (PCV), and live weight (LW). On D42, the sheep were again dewormed and submitted to a new parasitic challenge, following the same scheme. The animals of each category (lambs and ewes) were ranked according to individual mean FEC values, and classified as resistant (R, 20%), intermediate (I, 60%), or susceptible (S, 20%) to H. contortus infection. At weaning, high FEC were observed in all three phenotypes (P > 0.05). After the artificial infections, there was a significant difference (P < 0.05) among the three lamb phenotypes for the mean FEC (R < I < S), PCV (R > I > S), and LW (R = I > S). The infection levels (FEC) were negatively correlated with PCV (r = -0.66; P < 0.001), and LW (r = -0.30; P < 0.001). Despite this, the lambs were resilient, since more than 88% of these animals maintained the PCV above 24%, even when heavily infected. The importance of selective parasite control before weaning to reduce the negative impact on slaughter weight was evidenced, taking into account the high positive correlation between LW at weaning and final LW (r = 0.73; P < 0.001). The ewes, in turn, were strongly resistant to the parasite. Despite highly significant differences (P < 0.001) for mean FEC between phenotypes (R < I < S), 98% of the ewes maintained FEC below 4000 EPG. Their health was not affected, since PCV and LW did not differ between phenotypes, and these parameters were not significantly correlated with FEC (P > 0.05). With the phenotypic characterization performed here, it is possible to introduce procedures for parasite control in Morada Nova flocks, facilitating the target-selective treatment approach. The results of this study can also support improvement of meat production by the Morada Nova breed.

1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal nematode (GIN) infections are considered the main constraint of sheep farming, especially in tropical countries. Economic losses are high as a result of the decline in productivity and fertility, mortality of heavily infected animals, and large expenses for anthelmintics (O’Connor et al., 2007). Among these parasites, Haemonchus contortus, a highly pathogenic species, has the greatest clinical and economic importance in Brazil (Cavalcante et al., 2009, Chagas et al., 2013). Due to the enormous biotic potential of this parasite, and the favorable climate in most of Brazil, it has high prevalence in sheep flocks, including in São Paulo state (Amarante et al., 2004, Chagas et al., 2008).

Another major obstacle to sheep farming is the increasing resistance of GINs to anthelmintics. Due to the inappropriate use of these drugs, neglecting the biology and epidemiology of parasites, this resistance is already widespread to many of the available active principles (Coles et al., 2006, Almeida et al., 2010, Veríssimo et al., 2012). Monepantel, a recent and expensive drug, is the only alternative for GIN control in many Brazilian flocks, despite recent reports of resistance to this chemical group as well (Cintra et al., 2016, Albuquerque et al., 2017, Martins et al., 2017).

GIN-infected animals have three basic phenotypes in relation to establishment of the host-parasite relationship: resilient, resistant or susceptible (Woolaston and Baker, 1996). Resilient animals are those capable of remaining healthy and productive despite high levels of infection, that is, they can tolerate the damages caused by parasitism (Albers et al., 1981; Bisset et al., 2001). Resistance is the host immune system’s ability to prevent or reduce the occurrence of parasitic infection, preventing the establishment of infective larvae and/or rejecting those already implanted (Albers et al., 1987). Susceptibility, in turn, is the absence of resistance or resilience, resulting in inability to prevent infection and the consequences of parasitism, such as decrease in production and health (Woolaston and Baker, 1996). Both resistant and resilient phenotypes have been studied regarding genetic selection of sheep, in order to avoid the high losses caused by H. contortus parasitism (Albers et al., 1987, Bishop et al., 1996, Assenza et al., 2014).

Selecting resilient animals is a controversial subject. In theory, the selection of animals with this phenotype would allow a harmonic host-parasite interaction, maintaining good productive levels even when heavily infected. However, due to high fecal egg counts (FEC), these animals are important sources of pasture contamination with infective larvae, a situation particularly damaging to naturally susceptible animals, such as lambs and females in peripartum (Albers et al., 1987). In addition, selecting sheep for resilience to H. contortus infection would be the same as breeding animals capable of living with constant hemorrhaging (Le Jambre, 1994). Under heavy infections, inadequate nutritional status or pathophysiological conditions that result in immune suppression, these individuals could become susceptible and suffer the consequences of parasitism, such as sudden death due to hyperacute haemonchosis (Amarante et al., 2004, Burke and Miller, 2008). Nevertheless, the estimated heritability of resilience to H. contortus in sheep is extremely low (0.09 ± 0.07), so good genetic progress would be hard to achieve (Albers et al., 1987).

Selection of hosts resistant to GINs, in turn, is widely accepted as an effective alternative control method, and FEC assessment in natural (Bisset et al., 2001) or artificial infection (Aguerre et al., 2018) is the main phenotypic tool to classify GIN resistant sheep. By harboring fewer parasites, resistant animals do not suffer the consequences of infection, and their lower FEC allows a significant reduction of pasture contamination (Woolaston and Baker, 1996, Bisset et al., 1997). In addition, the need for anthelmintic treatments is significantly reduced, thus maintaining the efficacy of the active principles and reducing the selection of resistant parasites. In this respect, several studies have obtained successful results for the identification and selection of GIN-resistant sheep, even with initially susceptible breeds (Woolaston et al., 1990, Bisset et al., 1996, Gruner et al., 2002). Moderate heritabilities for this characteristic (0.2 to 0.5), measured by FEC, suggest potential for genetic progress of flocks (Bishop et al., 1996, Assenza et al., 2014, Aguerre et al., 2018).

In general, sheep breeds adapted to tropical conditions are very resistant to GINs, an important trait due to the impact of these parasites on the sheep industry (Amarante et al., 2004, Rocha et al., 2005). In this context, the Morada Nova breed, naturalized and traditionally raised in Northeast Brazil, stands out among others. One study compared the performance of two GIN-resistant sheep breeds, Morada Nova and Santa Inês, naturally infected with H. contortus. The parasitism had a low impact on the health of the ewes of both breeds, especially the Morada Nova breed, which had the lowest FEC and highest packed cell volume (PCV) 30 days after lambing, which is a very critical period due to the increased infection levels (Issakowicz et al., 2016). This breed has other extremely desirable characteristics, such as rusticity, excellent adaptation to the tropical climate due to hundreds of years of natural selection, sexual precocity and prolificacy, lack of reproductive seasonality, excellent maternal ability, and high meat and leather quality (Facó et al., 2008, Gomes et al., 2013).

Due to the good potential of the Morada Nova breed, we carried out a pilot study (Chagas et al., 2015) to evaluate the GIN resistance of this breed compared to others raised in the Embrapa Southeast Livestock Research Center (CPPSE/Embrapa Pecuária Sudeste – São Carlos, SP). During the whole experimental period, the Morada Nova flock was very resistant to natural H. contortus infection, showing very low infection levels, with mean FEC of 158.8 ± 436.6 eggs per gram of feces (EPG), in addition to higher mean PCV (36.3 ± 2.6%) compared to the other breeds: Santa Inês (29.5 ± 1.9%), Dorper (25.9 ± 3.3%), and Texel (26.9 ± 1.4%). These results, along with the lack of research on Morada Nova sheep, led to the present study, which aimed to evaluate the level of resistance through phenotypic markers, in order to characterize the resistance variability within and between categories (lambs and ewes).

2. Material and methods

2.1. Experimental animals and management

The present experiment was conducted in the Morada Nova flock of CPPSE/Embrapa, maintained in the municipality of São Carlos, São Paulo state, Brazil. Experimental sheep flocks from CPPSE are routinely monitored and the parasite control occurs by target-selective treatment (TST) when animals present with FEC ≥ 4000 EPG, and/or PCV ≤ 20% and/or Famacha score ≥ 4 (Chagas et al., 2014).

A total of 123 Morada Nova ewes, between 2 and 9 years of age, were mated with 4 rams, in two naturally controlled mating seasons of 60 days, in 2016 and 2017. From this breeding, 151 lambs were obtained in the first mating season, born between April and May 2017, and 136 lambs in the second season, born between March and May 2018. Therefore, a total of 287 Morada Nova lambs were obtained, 146 males and 141 females, with birthweights between 1.10 kg and 4.20 kg (average of 2.74 ± 0.58 kg). Of these animals, 208 came from single births, 76 from twin births and three from triple births.

The ewes were raised together in a field covering 3 ha of predominantly Aruana grass (Panicum maximum cv. Aruana), in a rotational grazing system with 12 paddocks, fertilized in the summer with 100 kg/ha of urea every 50 days. In the summer (rainy season), the ewes were fed exclusively in pasture, and in the dry season they were supplemented with corn silage or grass silage plus pelleted citrus pulp. Water and mineral salt were provided ad libitum throughout the experiment. The suckling lambs were kept with their mothers, and fed in a creep feeding system, from 10 days of age until weaning, with concentrate composed of 58.8% milled corn kernels, 39% soybean bran, 1.2% calcitic limestone and 1.0% mineral salt for sheep. The bromatological composition of this diet consisted of 85% dry matter (DM), 22.2% crude protein (CP), 71.8% total digestible nutrients (TDN), 0.63% calcium and 0.43% phosphorus. The concentrate was initially supplied in a ratio of about 0.5% of live weight (LW) per day, gradually increasing to 1.5%. At approximately 100 days of age (average of 98.67 ± 8.95 days), the lambs were weaned and transferred to four paddocks with approximate area of 960 m2 covered with star grass (Cynodon sp.). The animals were separated by sex and lot (month of birth, in each experimental year). Food management was the same as for the ewes. No anthelmintic treatment was given to lambs prior to weaning, and ewes were dewormed at lambing.

2.2. Assessment of parasitological, blood and productive parameters

Immediately after weaning, fecal samples were collected from the 287 lambs in order to perform FEC (Ueno and Gonçalves, 1998). They were treated with monepantel (Zolvix®, Novartis) at 2.5 mg/kg body weight, in order to eliminate natural infections (confirmed by two FEC, 7 and 14 days after treatment). After 15 days, the lambs were artificially infected with 4000 H. contortus L3, from an isolate susceptible to different anthelmintic groups (Echevarria et al. (1991)), following the recommendations of the World Association for the Advancement of Veterinary Parasitology (Wood et al., 1995). Fecal samples were collected individually for FEC at D0, D21, D28, D35, and D42. Blood samples were collected biweekly for determination of PCV on D0, D14, D28, and D42.

After D42 of the first artificial infection, the lambs were once again dewormed with Zolvix®, and after 15 days, subjected to a new parasitic challenge with 4000 L3 of the same H. contortus isolate previously described, following the same sampling method. Although the pasture was kept free of animals for 3 months before the beginning of the experiment, the animals were also subject to natural infection by parasites. Therefore, fecal cultures (Roberts and O’Sullivan, 1950) from a feces pool were performed at weaning and on D42 of each parasitic challenge, and the infective larvae recovered from the cultures were identified as described by Keith (1953).

In order to evaluate the productivity of lambs, they were weighed at birth, at weaning and on D0, D28, D56, D84, and D112, counted from the first parasitic challenge. Considering the age difference between the growing lambs, the live weight (LW) was adjusted in relation to the oldest lamb of each lot, considering the average daily weight gain (DWG) and the age difference (Δage), in days, between that lamb and the oldest one, on that weighing date. The adjusted live weight (LWADJ) was calculated by the formula: LWADJ = LW + DWG ∙ Δage.

Immediately after weaning of the lambs, individual fecal samples were collected from the 123 Morada Nova ewes, and FEC were performed in order to evaluate their natural GIN infection status. Fecal culture from a feces pool was also performed, as described for the lambs. On this same collection date, these animals were dewormed with monepantel at 2.5 mg/kg body weight, and 15 days later were experimentally infected with 4000 H. contortus L3 of the same isolate used for the artificial infections of the lambs. The ewes were submitted to periodic blood and feces collection, and weighing, in two parasitic challenges, following the same procedures and timeline described for the lambs.

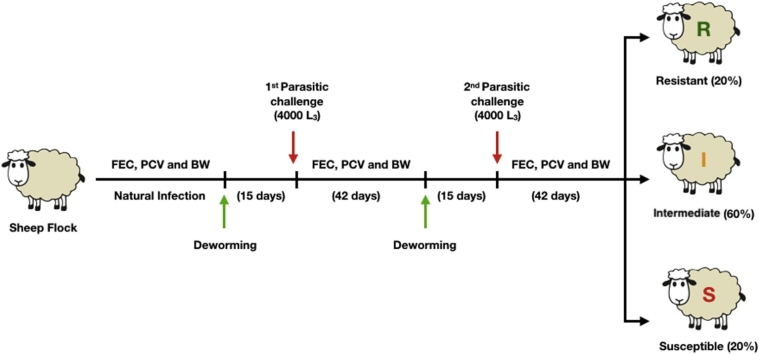

2.3. Phenotypic classification

At D42 of the second parasitic challenge, the animals were ranked based on the individual mean FEC between the two parasitic challenges, excluding post-deworming values (D0 of each challenge). From each category (lambs or ewes), the 20% of the flock with the lowest mean FEC values were phenotypically classified as the resistant group (20%), the 20% with the highest mean FEC values as the susceptible group, and the 60% remaining 60% as the intermediate group. Resistant, intermediate or susceptible lambs remained in their respective phenotypic groups even when ranked based considering only on mean FEC values for the first or only the second challenge. Therefore, the mean FEC between the two parasitic challenges was chosen for the phenotypic classification. Fig. 1 represents the experimental design adopted for the phenotypic classification of the lambs and ewes.

Fig. 1.

Phenotyping scheme adopted to assess the level of resistance against Haemonchus contortus infection of the 287 lambs and 123 ewes.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The FEC values of the lambs and ewes were subjected to a Box-Cox analysis, and then transformed into (FEC + 1)0.37, in order to normalize the model residuals and stabilize the variances. The FEC (transformed), PCV, and LW/LWADJ were analyzed with linear mixed effects models, with repeated measures of the same animal. For lambs, the model included the fixed effects of phenotype, sex, birth type, parasitic challenge, and interactions. The variable “animal” nested in “lot” was included as the random effect. For the ewes, the fixed effects included in the model were phenotype, age, parasitic challenge, and interactions. The variable “animal” was included as random effect. In all models, an autoregressive order 1 variance-covariance matrix was adopted, selected by the Akaike (AIC) and Bayesian (BIC) information criteria. The least square means were compared by the Tukey test. To correlate the variables, the Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated. All analyses were performed using the statistical package RStudio (version 1.1.463), with 5% significant level, and the graphs were plotted using GraphPad Prism (version 7.0a). The results are reported as arithmetic means (± standard errors) of untransformed data.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of lambs

3.1.1. Natural infection state

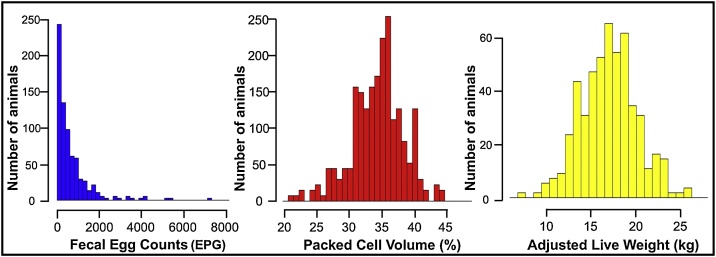

At weaning, the 287 lambs had natural infections, with FEC ranging from 0 to 71350 EPG, mean and standard deviation of 6643 ± 8994 EPG. Eggs of Strongyloides papillosus, Moniezia sp. and oocysts of Eimeria spp. were observed in the feces of several animals. Fecal culture revealed predominance of the genus Haemonchus (96.4%), followed by Cooperia (2.1%), and Trichostrongylus (1.5%). A total of 137 lambs (47.74%) had FEC higher than 4000 EPG, the cutoff point for deworming normally used for monitoring the CPPSE sheep flocks. PCV ranged from 17% to 45%, with an average of 33.05 ± 4.87%. Among the 137 lambs with FEC higher than 4000 EPG, only 11.68% (n = 16) had PCV below the normal range for sheep (PCV ≤ 24%). That is, 88.32% of these heavily infected animals maintained the PCV within the parameters of normality for the species. The weaning LWADJ of the lambs ranged from 6.55 kg to 27.20 kg, with mean LWADJ of 17.59 ± 3.54 kg. Fig. 2 shows the frequency distribution of the 287 lambs for FEC, PCV, and LWADJ at weaning.

Fig. 2.

Frequency distribution of the 287 Morada Nova lambs in relation to fecal egg count (FEC), packed cell volume (PCV) and adjusted live weight (LWADJ), at weaning.

3.1.2. Parasitological parameters: fecal egg counts

The infection levels at weaning were influenced by sex (P < 0.05), where males had higher mean FEC (7431.96 ± 811.98 EPG) than females (5843.48 ± 705.14 EPG). Although there was no difference among the three phenotypic groups (P > 0.05), the proportion of lambs that would be dewormed at weaning according to the TST was different. Of the 137 lambs with FEC ≥ 4000 EPG, 16.06% (n = 22) belonged to the resistant group, 62.04% (n = 85) to the intermediate group, and the remaining 21.90% (n = 30) to the susceptible group. Separate analysis of the phenotypic groups indicated that 38.60% of the resistant group, 49.13% of the intermediate group and 52.63% of the susceptible could have received anthelmintic treatment at weaning.

The experimental design permitted a clear stratification of the flock into the three significantly different (P < 0.001) phenotypic groups based on the mean FEC. With respect to the overall mean of the two parasitic challenges, the lowest mean FEC was observed in the resistant group (695.63 ± 53.27 EPG), followed by the intermediate group (4026.62 ± 119.47 EPG), and the highest mean FEC was found in the susceptible group (11390.02 ± 500.76 EPG). FEC values were influenced by sex (P < 0.001), and the females (3462.99 ± 171.65 EPG) were more resistant than the males (6180.95 ± 223.92 EPG).

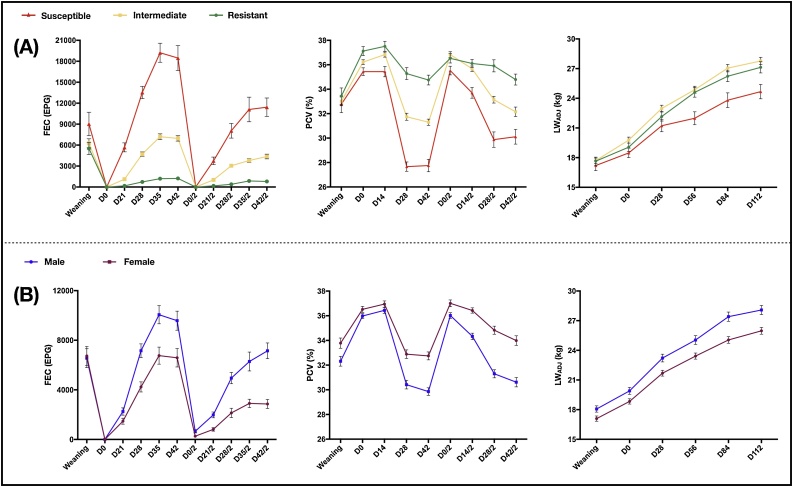

The mean FEC values differed significantly (P < 0.001) between first and second parasitic challenges, and there was a significant phenotype-challenge interaction (P < 0.001), so the phenotypic groups were analyzed separately. Resistant animals did not differ between parasitic challenges. For the other phenotypic groups, the mean FEC values were lower in the second challenge, both for the intermediate group, with mean FEC of 5015.65 ± 186.83 EPG (first challenge) and 3047.80 ± 139.68 EPG (second challenge), and the susceptible group, with mean FEC of 14205.06 ± 715.484 EPG (first challenge) and 8537.28 ± 648.52 EPG (second challenge). The mean FEC also differed between first and second parasitic challenges both for the males (7279.25 ± 334.76 EPG and 5080.72 ± 290.49 EPG, respectively) and the females (4770.95 ± 293.49 EPG and 2171.49 ± 162.64 EPG, respectively). All the fecal cultures performed at the end of each parasite challenge revealed 100% Haemonchus infection. The mean FEC values from weaning to the end of the second parasitic challenge, according to the phenotypic group and sex, are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Mean values of the fecal egg count (FEC), packed cell volume (PCV) and adjusted live weight (LWADJ) of the 287 Morada Nova lambs, according to the phenotypic group (A) and according to sex (B), at weaning and throughout the two parasitic challenges. Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean (SE).

On D42 of the first parasitic challenge, 58.54% of the lambs (n = 168) had FEC ≥ 4000 EPG. When the phenotypic groups were analyzed separately, 5.26% (n = 3) of the resistant, 65.32% (n = 113) of the intermediate, and 91.23% (n = 52) of the susceptible group should have been dewormed on D42 of the first challenge. In the second challenge, however, there was a reduction in the number of animals requiring anthelmintic treatment, and 37.63% (n = 108) of the lambs had FEC ≥ 4000 EPG. The number of animals with high FEC also decreased within the three phenotypic groups, with the lowest proportion observed in the resistant (1.75%, n = 1), followed by the intermediate (38.73%, n = 67) and the susceptible group (70.18%, n = 40).

3.1.3. Blood parameters: packed cell volume

At weaning, there was a significant effect of sex (P < 0.05) on PCV, and the highest mean PCV was found in females (33.75 ± 1.71%) in comparison to males (32.50 ± 1.71%). Among the 16 lambs with PCV ≤ 24%, 12.50% (n = 2) were resistant, 56.25% (n = 9) were intermediate and 31.25% (n = 5) were susceptible. Analysis of the phenotypic groups separately showed that only 3.51% of the resistant group, 5.20% of the intermediate and 8.77% of the susceptible group had PCV ≤ 24%.

Throughout the parasitic challenges, the PCV differed significantly (P < 0.001) between phenotypic groups. The highest mean PCV was observed in the resistant group (35.20 ± 0.39%), followed by the intermediate (33.67 ± 0.31%) and susceptible group (31.10 ± 0.39%). The mean PCV values also differed significantly (P < 0.001) between males (32.49 ± 0.33%) and females (34.15 ± 0.33%).

The mean PCV differed significantly (P < 0.01) between parasitic challenges, and there were significant phenotype-challenge and sex-challenge interactions (P < 0.01). The mean PCV of the resistant group did not differ between first and second parasitic challenges. The mean PCV of the intermediate group was lower in the first challenge (33.30 ± 0.34%) than in the second challenge (34.03 ± 0.34%). The susceptible group followed the same pattern, and the mean PCV values were 30.35 ± 0.45% in the first challenge and 31.86 ± 0.45% in the second challenge. The mean PCV of the females also differed between the first (33.51 ± 0.36%) and second challenge (34.80 ± 0.36%). Fig. 3 shows the mean PCV values at weaning and throughout the experiment of each parasitic challenge, according to the phenotypic group and sex.

On D42 of the first parasitic challenge, only a small proportion of the flock (5.23%, n = 15) had PCV values below the normal range for sheep (PCV ≤ 24%), corresponding to 12.96% of the lambs with FEC ≥ 4000 EPG. Analysis of the phenotypic groups separately revealed that no lambs from the resistant group, 2.31% (n = 4) of the intermediate group and 19.30% (n = 11 animals) of the susceptible group had PCV ≤ 24%. In the second challenge, despite the smaller proportion of lambs with FEC above 4000 EPG, the number of animals with PCV ≤ 24% did not differ from the first challenge. However, the proportion within the phenotypic groups was different, with absence of lambs with PCV ≤ 24% in the resistant group, 4.62% (n = 8) in the intermediate and 12.28% (n = 7) in the susceptible group.

3.1.4. Productive parameters: adjusted live weight

At weaning, the mean LWADJ differed significantly between the phenotypic groups (P < 0.05), and the lambs classified as the resistant group were heavier (18.27 ± 0.95 kg) than those of the susceptible group (16.55 ± 0.94 kg). The mean LWADJ of the intermediate group (17.68 ± 0.87 kg) did not differ significantly from any of the other groups (P > 0.05). The LWADJ at weaning differed significantly between sexes (P < 0.001), and males (18.14 ± 0.89 kg) were heavier than females (16.86 ± 0.89 kg).

Throughout the parasitic challenges, the mean LWADJ differed significantly between the phenotypic groups (P < 0.01). On D0 of the first challenge, the mean LWADJ followed the same pattern observed at weaning for the phenotypic groups. However, on D28, the resistant and intermediate groups did not differ significantly from each other (P > 0.05), and both were heavier than the susceptible group (P < 0.05). This same pattern was observed until D112 (after D42 of the second parasitic challenge), when the mean LWADJ values were for 28.34 ± 0.94 kg for the resistant group, 27.65 ± 0.47 kg for the intermediate group and 23.76 ± 0.74 kg for the susceptible group. The LWADJ also differed significantly (P < 0.01) between sexes. Males were heavier than females on all experimental dates, and their final mean LWADJ values (D112) were, respectively: 28.16 ± 0.69 kg and 25.00 ± 0.56 kg. Fig. 3 shows the mean LWADJ values at weaning and throughout the parasitic challenges, according to the phenotypic group and sex.

3.1.5. Correlation analysis

Haemonchus contortus infection had a negative impact on the blood parameters of the lambs: higher FEC was associated with lower PCV. This pattern was observed at weaning (r = -0.61; P < 0.001) and throughout the parasitic challenges (r = -0.66; P < 0.001). The final LWADJ was positively correlated with the birthweight (r = 0.33; P < 0.001) and with LWADJ at weaning (r = 0.73; P < 0.001). The parasitic infection impaired productivity, and negative correlations between FEC and LWADJ were observed at weaning (r = -0.23; P < 0.001) and on D112 (r = -0.30; P < 0.001). On the other hand, animals with higher PCV values during parasitic infections had higher LWADJ. These traits were positively correlated at weaning (r = 0.38, P < 0.001) and on D112 (r = 0.34, P < 0.001).

3.2. Analysis of ewes

3.2.1. Natural infection state

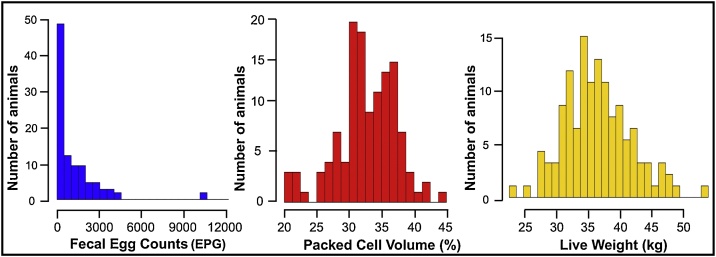

At the beginning of the experiment (D-14), the 123 ewes were naturally infected with GINs, and the individual FEC ranged from 0 to 10100 EPG, with mean and standard deviation of 1188.57 ± 1696.58 EPG. Haemonchus (98%) was the predominant genus recovered from fecal cultures, followed by Cooperia (2%). Only 3.25% (n = 4) of the ewes had FEC ≥ 4000 EPG on D-14, and the statistical analysis identified these values as outliers. The maximum individual FEC value, disregarding these outliers, was 3750 EPG. The PCV ranged from 24% to 44%, with mean and standard deviation of 34.62 ± 3.70%. Only 0.81% (n = 1) of the ewes had PCV below the normal level for sheep (PCV ≤ 24%). At D-14, the ewes had LW ranged from 24.50 kg to 51.20 kg, with mean and standard deviation of 36.50 ± 4.66 kg. Fig. 4 shows the frequency distribution of the 123 naturally infected ewes for FEC, PCV and LW on D-14.

Fig. 4.

Frequency distribution of the 123 Morada Nova ewes in relation to fecal egg count (FEC), packed cell volume (PCV) and live weight (LW) at the beginning of the study (natural infection, D-14).

3.2.2. Parasitological parameters: fecal egg counts

The mean FEC of the ewes with natural infection (D-14) differed significantly between the phenotypic groups (P < 0.001), and the three groups differed from each other by the Tukey test. The resistant group had 55.00 ± 19.50 EPG, the intermediate group presented 958.59 ± 107.64 EPG, and the susceptible group presented 2969.05 ± 611.08 EPG. The four ewes with FEC ≥ 4000 EPG belonged to the susceptible group.

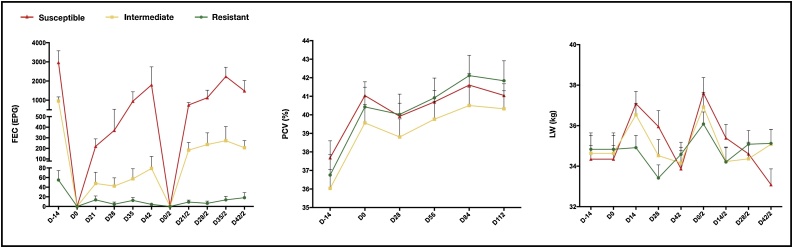

After D42 of the second parasitic challenge, the phenotypic classification permitted the stratification of the ewes into three significantly different groups, based on FEC (P < 0.001). The mean FEC values were 10.28 ± 2.29 EPG in the resistant group, 139.51 ± 13.22 EPG in the intermediate group, and 1133.31 ± 177.89 EPG in the susceptible group. There was no significant difference (P > 0.05) between first and second parasitic challenges for any of the phenotypic groups. However, the mean FEC values of the parasitic challenges were lower than those observed on D-14 (P < 0.01). Only 1.63% of the ewes (n = 2) had FEC ≥ 4000 EPG when artificially infected, and both animals were from the susceptible group. Fecal cultures performed at the end of the artificial infections (D42) revealed 100% Haemonchus. The mean FEC values for the ewes at the beginning of the experiment (D-14) and throughout the parasitic challenges, separated by phenotypic groups, are shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Mean values of the fecal egg count (FEC), packed cell volume (PCV) and live weight (LW) of the 123 Morada Nova ewes, according to the phenotypic group, at the beginning of the study (natural infection, D-14) and throughout the two parasitic challenges. Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean (SE).

3.2.3. Blood parameters: packed cell volume

The PCV of the ewes with natural infection (D -14) was not influenced by any of the fixed effects included in the model (P > 0.05). The only animal with PV ≤ 24% belonged to the intermediate group, and the FEC was 1950 EPG. Throughout the parasitic challenges, the same pattern was maintained, and phenotypic groups did not differ significantly from each other (P > 0.05). There was also no significant difference (P > 0.05) between parasitic challenges for mean PCV. Only one ewe, from the susceptible group, had PCV below the normal range for sheep, at both the first (FEC = 21300 EPG and PCV = 23%) and second challenge (FEC = 2800 EPG and PCV = 24%). Fig. 5 shows the mean PCV values of the ewes, separated by phenotypic group, from the beginning of the experiment (D-14) to the end of the second parasitic challenge.

3.2.4. Productive parameters: live weight

The mean LW of the ewes did not differ between the three phenotypic groups (P > 0.05) on D-14 (natural infection) and in both parasitic challenges. Also, the mean LW did not differ between parasitic challenges (P > 0.05). Fig. 5 shows the mean LW values of the ewes, separated by phenotypic group, from the beginning of the experiment (D-14) to the end of the second parasitic challenge.

3.2.5. Correlation analysis

For the ewes, all pairwise correlations between FEC, PCV and LW were very low and not significant (P > 0.05). However, these variables were positively correlated when comparing their measurements on D-14 and the means between the two parasitic challenges. This was observed for FEC (r = 0.55, P < 0.001), PCV (r = 0.63, P < 0.001), and more intensely, for LW (r = 0.87, P < 0.001).

4. Discussion

In the present study, natural infection with a predominance of H. contortus was detected, corresponding to almost all of the L3 recovered from the lamb and ewe fecal cultures, similar to previous reports for other sheep flocks raised at CPPSE/Embrapa (Chagas et al., 2008, Chagas et al., 2015, Gonçalves et al., 2018), as well as in other regions of São Paulo state (Amarante et al., 2004, Louvandini et al., 2006).

The ability of sheep to withstand parasitic infections is strongly influenced by a number of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, including breed, age, physiological status, nutrition and environment. Among these factors the age of the animals is an important cause of variation. Young animals have incomplete development of their immune system, especially between four and eight months of age, when they have lower counts of CD4+ cells compared to adult sheep, and this cell group is essential for immunity against helminths (Watson et al., 1994, Colditz et al., 1996). In addition, another important cause of the high susceptibility found in young lambs is the stress of weaning (Watson and Gill, 1991). In the present study, the Morada Nova lambs were highly susceptible to H. contortus infection compared to the ewes. This difference in susceptibility between young and adult sheep was also found by other studies, comparing animals raised under the same management conditions (Coldiz et al., 1996; Vanimisetti et al., 2004).

The ewes evaluated in the present study showed high resistance to H. contortus infection. Despite the clear distinction between the three phenotypes, their FEC remained relatively low throughout the experimental period. This behavior was observed under natural infection, when only four ewes, all susceptible, had FEC above the threshold for TST. Throughout the challenges, this pattern was maintained, and only two ewes had counts indicating the need for deworming. That is, 98.37% of this flock had FEC below 4000 EPG. Issakowicz et al. (2016) found similar results when comparing the performance of ewes of Morada Nova and Santa Inês breeds under GIN infections. Both breeds were resistant to natural H. contortus infection, and FEC values remained well below 4000 EPG. The authors observed an increase in the infection levels from the final third of pregnancy until two months postpartum. Nevertheless, even in this critical period, the females from both breeds remained below the TST threshold (4000 EPG), especially the Morada Nova ewes, which had the lowest FEC values and Famacha scores, and higher PCV values on the 30th day postpartum.

The higher infection levels found in the ewes at the beginning of the present experiment can be attributed to the fact that these flocks remained at least five months without receiving anthelmintics and were constantly exposed to the infective larvae present in the pasture. Moreover, these animals were recovering from the deficient nutrition and relaxed immunity due to postpartum and lactation, which are important causes of increased infection levels (Zajac et al., 1988, Woolaston, 1992).

In addition to the age effect on the maturation of the immune system in order to acquire resistance against helminths, another important directly related factor is previous exposure to parasites. At weaning, high FEC values were observed in all lambs of the present study, and the phenotypic groups did not differ. However, by subjecting these animals to a second artificial infection, there was a clear distinction among the phenotypic groups. All lambs had a significant reduction in FEC values, similar to the findings previously reported by Gamble and Zajac (1992). These authors evaluated two breeds, characterized as resistant (St. Croix) and susceptible (Dorset) to H. contortus, under natural or artificial infection, and the mean FEC values did not differ between breeds when comparing two-month-old lambs. When the animals were submitted to a new infection at four months of age, however, there was a clear phenotypic difference between the breeds. Other studies have found a considerable reduction in FEC and parasite loads in sheep after repeated infections by H. contortus, Trichostrongylus colubriformis and Teladorsagia circumcincta, when compared to primary infected animals (Aumont et al., 2003, Gruner et al., 2003).

In the present study, females had lower mean FEC values than males, at weaning and in both parasitic challenges. This pattern was observed for sheep in other studies (Courtney et al., 1985, Gruner et al., 2003, Gauly et al., 2006), and the immunosuppressive effect of testosterone could be a factor to consider. Gauly et al. (2006) found higher FEC and parasite load in males artificially infected with H. contortus, and these were positively correlated with serum testosterone levels.

The hematophagous parasite H. contortus causes varying degrees of anemia in its hosts, since L5 and adult helminths can ingest individually about 50 μL of blood per day (Clark et al., 1962). Assuming a heavy infection with 5000 parasites, the daily blood losses can reach 250 mL. Thus, in addition to coproparasitological examinations, evaluation of PCV is an important measure to evaluate the health status of infected sheep. In the present study, the parasitic infection had a negative impact on PCV in lambs, considering the difference among phenotypic groups and the negative correlations between PCV and FEC. Other studies have found similar results, with higher PCV values in resistant lambs, and negative correlations between this blood parameter and FEC (Amarante et al., 2009, Zaros et al., 2014, Pereira et al., 2016; Gonçalves et al., 2018).

Despite the impact of haemonchosis on sheep, there are some resilient animals, which are able to stay healthy even when infected. This behavior was observed in the Morada Nova lambs, evidenced by the low percentage of animals with PCV ≤ 24%, even when the FEC values were high. Fernandes Júnior et al. (2015) found similar results when comparing Morada Nova, Santa Inês and Brazilian Somalis lambs. Morada Nova lambs stood out, presenting Famacha score below 3 and PCV above 23%, even with higher FEC values.

Due to the low FEC values observed for the ewes in the present study, their PCV was not affected, even in the susceptible group. Mean PCV values did not differ significantly (P > 0.05) between phenotypic groups, and there were no significant correlations between this variable and FEC. In addition, there was a virtual absence of animals with PCV ≤ 24% (n = 1). Similarly, Issakowicz et al. (2016) found that H. contortus infection also had no impact on PCV of naturally infected Morada Nova ewes.

In the present study, H. contortus infection impaired lamb performance, considering the lower mean LWADJ observed in the susceptible group, from weaning to the end of the study (D112), in addition to negative correlations with FEC. GIN-infected sheep have lower final LW in comparison to parasite-free animals (Coop et al., 1977, Coop et al., 1988). Dewormed animals can have weight gain approximately twice as high as untreated ones (Laurenson et al., 2016, Keegan et al., 2018). In the present study, the mean LWADJ did not differ between resistant and intermediate groups. This may have been due to the resilient character of the latter, which remained productive even under higher infection levels. Similar results were obtained by Greer et al. (2005) and Idika et al. (2012) when comparing lambs with different phenotypes regarding resistance to GIN infections. In both studies, the resistant lambs had superior weight gain and final LW in comparison to the susceptible groups. The ewes evaluated in the present study, on the other hand, did not suffer any impact of H. contortus infection on their LW, due to the low infection levels and high PCV values.

The lambs of the Morada Nova flock evaluated in the present study were characterized as resilient, since more than 80% of the animals maintained PCV within normal range for the species, even when heavily infected. However, H. contortus parasitism had a negative impact on their PCV and LWADJ, especially at weaning, when infection levels were quite high and the mean FEC values did not differ between phenotypic groups. This result, along with the high positive correlation between LWADJ at weaning and final LWADJ, highlights the importance of TST deworming before weaning. Perhaps 30 days before would be advisable due to the higher percentage of solid ingestion that occurs at this age. The ewes, on the other hand, were highly resistant, since more than 98% of the flock had FEC below 4000 EPG, which did not affect their PCV or LW. Notably, the sheep classification did not change between parasitic challenges, since the classified animals remained within their respective phenotypic groups. So, only one challenge can be performed to have a clear stratification of the Morada Nova sheep flock regarding the level of resistance to H. contortus, using FEC as a phenotypic tool.

5. Conclusion

The results generated in the present study can promote more efficient sheep meat production, highlighting the potential of the Morada Nova breed. In intensive grazing production systems, with the suitable nutritional supplementation when necessary, we recommend TST deworming of the lambs before weaning, which would allow them to express their real productive potential. Moreover, since the resistant and intermediate groups did not differ from each other in relation to LWADJ, the focus of the TST control should be the susceptible lambs, with special attention to males. On the other hand, the resistance observed in the ewes indicated low need for deworming in this category. Therefore, it is important to remove from the flock ewes that require routine anthelmintic treatment. Keeping lambs and ewes together would probably reduce the infestation of the pasture by ingestion of the GIN infective larvae by the latter category. With the resilience and resistance characteristics detected in this experiment, it would be possible to introduce procedures for GIN control in Morada Nova flocks, through the TST approach. These recommendations would facilitate flock management, reduce anthelmintic treatments and costs of the production system. As a consequence, the pressure for parasite resistance would decrease, maintaining the effectiveness of the active principles available.

Ethical approval

All procedures were approved by the Embrapa Pecuária Sudeste Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation (process no. 04/2017), and are in accordance with national and international principles and guidelines for animal experimentation adopted by the Brazilian College of Experimentation (CONCEA).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) for funding this study (grant no.2017/01626-1), and for the scholarships (grant no. 2017/00373-2 and no. 2017/24289-0). We also thank Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the scholarship provided (grant no. 131537/2018-0). Finally, we are grateful to the Veterinary Parasitology Laboratory trainees and technicians for their technical support.

References

- Aguerre S., Jacquiet P., Brodier H., Bournazel J.P., Grisez C., Prévot F., Michot L., Fidelle F., Astruc J.M., Moreno C.R. Resistance to gastrointestinal nematodes in dairy sheep: genetic variability and relevance of artificial infection of nucleus rams to select for resistant ewes on farms. Vet. Parasitol. 2018;256:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albers G.A.A., Gray G.D., Piper L.R., Barker J.S.F., Le Jambre L.F., Barger I.A. The genetics of resistance and resilience to Haemonchus contortus infection in young merino sheep. Int. J. Parasitol. 1987;17:1355–1363. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(87)90103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque A.C.A., Bassetto C.C., Almeida F.A., Amarante A.F.T. Development of Haemonchus contortus resistance in sheep under suppressive or targeted selective treatment with monepantel. Vet. Parasitol. 2017;246:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida F.A., Garcia K.C., Torgerson P.R., Amarante A.F.T. Multiple resistance to anthelmintics by Haemonchus contortus and Trichostrongylus colubriformis in sheep in Brazil. Parasitol. Int. 2010;59:622–625. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amarante A.F.T., Bricarello P.A., Rocha R.A., Gennari S.M. Resistance of Santa Inês, Suffolk and Ile de France sheep to naturally acquired gastrointestinal nematode infections. Vet. Parasitol. 2004;120:91–106. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amarante A.F.T., Susin I., Rocha R.A., Silva M.B., Mendes C.Q., Pires A.V. Resistance of Santa Ines and crossbred ewes to naturally acquired gastrointestinal nematode infections. Vet. Parasitol. 2009;165:273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assenza F., Elsen J.M., Legarra A., Carré C., Sallé G., Robert-Granié C., Moreno C.R. Genetic parameters for growth and faecal worm egg count following Haemonchus contortus experimental infestations using pedigree and molecular information. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2014;46:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-46-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumont G., Gruner L., Hostache G. Comparison of the resistance to sympatric and allopatric isolates of Haemonchus contortus of Black Belly sheep in Guadeloupe (FWI) and of INRA 401 sheep in France. Vet. Parasitol. 2003;116:139–150. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(03)00259-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop S.C., Bairden K., NcKellar Q.A., Park M., Stear M.J. Genetic parameters for faecal egg count following mixed, natural predominantly Ostertagia circumcincta infection and relationships with live weight in young lambs. Anim. Sci. 1996;63:423–428. [Google Scholar]

- Bisset S.A., Vlassoff A., Douch P.G., Jonas W.E., West C.J., Green R.S. Nematode burdens and immunological responses following natural challenge in Romney lambs selectively bred for low or high faecal worm egg count. Vet. Parasitol. 1996;61:249–263. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(95)00836-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisset S.A., Vlassoff A., West C.J., Morrison L. Epidemiology of nematodosis in Romney lambs selectively bred for resistance or susceptibility to nematode infection. Vet. Parasitol. 1997;70:255–269. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(96)01148-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisset S.A., Morris C.A., McEwan J.C., Vlassoff A. Breeding sheep in New Zealand that are less reliant on anthelmintics to maintain health and productivity. New Zeal. Vet. J. 2001;49:236–246. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2001.36238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke J.M., Miller J.E. Use of FAMACHA system to evaluate gastrointestinal nematode resistance/resilience in offspring of stud rams. Vet. Parasitol. 2008;153:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante A.C.R., Vieira L.S., Chagas A.C.S., Molento M.B. 2009. Doenças parasitárias de caprinos e ovinos: epidemiologia e controle. Embrapa Informação Tecnológica, Brasília. 603 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Chagas A.C.S., Oliveira M.C.S., Esteves S.N., Oliveira H.N., Giglioti R., Giglioti C., Carvalho C., Ferrezini J., Schiavone D. Parasitismo por nematóides gastrintestinais em matrizes e cordeiros criados em São Carlos, São Paulo. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2008;17:126–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagas A.C.S., Katiki L.M., Silva I.C., Giglioti R., Esteves S.N., Oliveira M.C.S., Barioni Júnior W. Haemonchus contortus: a multiple-resistant Brazilian isolate and the costs for its characterization and maintenance for research use. Parasitol. Int. 2013;62:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagas A.C.S., Oliveira M.C.S., Esteves S.N. Modelo para monitoramento da resistência parasitária e tratamento antihelmíntico seletivo em rebanhos experimentais de ovinos e caprinos, Boletim de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento. Embrapa Pecuária Sudeste. 2014;36:22–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chagas A.C.S., Zaia M.G., Domingues L.F., Rabelo M.D., Politi F.A.Z., Anibal F.F., Chagas J.R. VII Congreso Argentino de Parasitología. Libro de Resúmenes… Associación Parasitológica Argentina; La Plata: 2015. Desparasitación racional: estudio comparativo de técnicas para la detección de la anemia causada por nemátodos gastrointestinales en pequeños rumiantes; p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- Cintra M.C., Teixeira V.N., Nascimento L.V., Sotomaior C.S. Lack of efficacy of monepantel against Trichostrongylus colubriformis in sheep in Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2016;216:4–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C.H., Kiesel G.K., Goby C.H. Measurement of blood loss caused by Haemonchus contortus. Am. J. Vet. Med. 1962;23:977–980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colditz I.G., Watson D.L., Gray G.D., Eady S.J. Some relationships between age, immune responsiveness and resistance to parasites in ruminants. Int. J. Parasitol. 1996;26:869–877. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(96)80058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles G.C., Jackson F., Pomroy W.E., Prichard R.K., von Samson-Himmelstjerna G., Silvestre A., Taylor M.A., Vercruysse J. The detection of anthelmintic resistance in nematodes of veterinary importance. Vet. Parasitol. 2006;136:167–185. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coop R.L., Sykes A.R., Angus K.W. The effect of a daily intake of Ostertagia circumcincta larvae on body weight, food intake and concentration of serum constituents in sheep. Res. Vet. Sci. 1977;23:76–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coop R.L., Jackson F., Graham R.B., Angus K.W. Influence of two levels of concurrent infection with Ostertagia circumcincta and Trichostrongylus vitrinus on the growth performance of lambs. Res. Vet. Sci. 1988;45:275–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney C.H., Parker C.F., McClure K.E., Herd R.P. Resistance of exotic and domestic lambs to experimental infection with Haemonchus contortus. Int. J. Parasitol. 1985;15:101–109. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(85)90107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria F.M.A., Armour J., Duncan J.L. Efficacy of some anthelmintics on an ivermectin-resistant strain of Haemonchus contortus in sheep. Vet. Parasitol. 1991;39:279–284. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(91)90044-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facó O., Paiva S.R., Alves L.R.N., Lobo R.N.B., Villela L.C.V. Raça Morada Nova: origem, características e perspectivas. Embrapa Caprinos, Sobral. 2008 43 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes Júnior G.A., Lôbo R.N.B., Vieira L.S., Sousa M.M., Lôbo A.M.B.O., Facó O. Performance and parasite control of different genetic groups of lambs finished in irrigated pasture. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2015;67:732–740. [Google Scholar]

- Gamble H.R., Zajac A.M. Resistance of St. Croix lambs to Haemonchus contortus in experimentally and naturally acquired infections. Vet. Parasitol. 1992;41:211–225. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(92)90081-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauly M., Schackert M., Hoffmann B., Erhardt G. Influence of sex on the resistance of sheep lambs to an experimental Haemonchus contortus infection. Dtsch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 2006;113:178–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes E.F., Louvandini H., Dallago B.S.L., Canozzi M.E.A., Melo C.B., Bernal F.E.M., Mcmanus C. Productivity in ewes of different genetic groups and body sizes. J. Anim. Sci. Adv. 2013;3:243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves T.C., Alencar M.M., Giglioti R., Bilhassi T.B., Oliveira H.N., Rabelo M.D., Esteves S.N., Oliveira M.C.S. Resistance of sheep from different genetic groups to gastrointestinal nematodes in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. Small Rumin. Res. 2018;166:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Greer A.W., Stankiewicz M., Jay N.P., McAnulty R.W., Sykes A.R. The effect of concurrent corticosteroid-induced immuno-suppression and infection with the intestinal parasite Trichostrongylus colubriformis on feed intake and utilization in both immunologically naive and competent sheep. Anim. Sci. 2005;80:89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Gruner L., Cortet J., Sauve C., Limouzin C., Brunel J.C. Evolution of nematode community in grazing sheep selected for resistance and susceptibility to Teladorsagia circumcincta and Trichostrongylus colubriformis: a 4-year experiment. Vet. Parasitol. 2002;109:277–291. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(02)00302-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruner L., Aumont G., Getachew T., Brunel J.C., Pery C., Cognie Y., Guerin Y. Experimental infection of Black Belly and INRA 401 straight and crossbred sheep with trichostrongyle nematode parasites. Vet. Parasitol. 2003;116:239–249. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idika I., Chiejina S., Mhomga L., Nnadi P., Ngongeh L. Correlates of resistance to gastrointestinal nematode infection in Nigerian West African dwarf sheep. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2012;5:529–532. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(12)60093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issakowicz J., Issakowicz A.C.K.S., Bueno M.S., Costa R.L.D., Katiki L.M., Geraldo A.T., Abdalla A.L., McManus C., Louvadini H. Parasitic infection, reproductive and productive performance from Santa Inês and Morada Nova ewes. Small Rumin. Res. 2016;136:96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Keegan J.D., Good B., Hanrahan J.P., Lynch C., de Waal T., Keane O.M. Live weight as a basis for targeted selective treatment of lambs post-weaning. Vet. Parasitol. 2018;258:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith R.K. The differentiation of infective larvae of some common nematode parasites of cattle. Aust. J. Zool. 1953;1:223–235. [Google Scholar]

- Laurenson Y.C., Kahn L.P., Bishop S.C., Kyriazakis I. Which is the best phenotypic trait for use in a targeted selective treatment strategy for growing lambs in temperate climates? Vet. Parasitol. 2016;226:174–188. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Jambre L.F. Relationship of blood loss to worm numbers, biomass and egg production in Haemonchus infected sheep. Int. J. Parasitol. 1994;25:269–273. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(94)00118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvandini H., Veloso C.F., Paludo G.R., Dell’Porto A., Gennari S.M., McManus C.M. Influence of protein supplementation on the resistance and resilience on young hair sheep naturally infected with gastrointestinal nematodes during rainy and dry seasons. Vet. Parasitol. 2006;137:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins A.C., Bergamasco P.L.F., Felippelli G., Tebaldi J.H., Duarte M.M.F., Testi A.J.P., Lapera I.M., Hoppe E.G.L. Haemonchus contortus resistance to monepantel in sheep: fecal egg count reduction tests and randomized controlled trials. Semin. Cienc.Agrar. 2017;38:231–238. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor L.J., Kahn L.P., Walkden-Brown S.W. The effects of amount, timing and distribution of simulated rainfall on the development of Haemonchus contortus to the infective larval stage. Vet. Parasitol. 2007;146:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira J.F.S., Mendes J.B., De Jong G., Maia D., Teixeira V.N., Passerino A.S., Garza J.J., Sotomaior C.S. FAMACHA© scores history of sheep characterized as resistant/resilient or susceptible to H. contortus in artificial infection challenge. Vet. Parasitol. 2016;218:102–105. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts F.H.S., O’Sullivan J.P. Methods for egg counts and larval cultures for strongyles infesting the gastro-intestinal tract of cattle. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1950;1:99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha R.A., Amarante A.F.T., Bricarello P.A. Resistance of Santa Inês and Ile de France suckling lambs to gastrointestinal nematode infections. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2005;14:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno H., Gonçalves P.C. Japan International Cooperation Agency; Tokyo: 1998. Manual para diagnóstico das helmintoses de ruminantes. 143 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Vanimisetti H.B., Andrew S.L., Zajac A.M., Notter D.R. Inheritance of fecal egg count and packed cell volume and their relationship with production traits in sheep infected with Haemonchus contortus. J. Anim. Sci. 2004;82:1602–1611. doi: 10.2527/2004.8261602x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veríssimo C.J., Niciura S.C., Alberti A.L., Rodrigues C.F., Barbosa C.M., Chiebao D.P., Cardoso D., da Silva G.S., Pereira J.R., Margatho L.F., da Costa R.L., Nardon R.F., Ueno T.E., Curci V.C., Molento M.B. Multidrug and multispecies resistance in sheep flocks from São Paulo state, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2012;187:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D.L., Gill H.S. Effect of weaning on antibody responses and nematode parasitism in Merino lambs. Res. Vet. Sci. 1991;51:128–132. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(91)90002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D.L., Colditz I.G., Andrew M., Gill H.S., Altmann K.G. Age-dependent immune response in Merino sheep. Res. Vet. Sci. 1994;57:152–158. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(94)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood I.B., Amaral N.K., Bairden K., Duncan J.L., Kassai T., Malone J.B., Jr, Pankavich J.A., Reinecke R.K., Slocombe O., Taylor S.M., Vercruysse J. World Association for the Advancement of Veterinary Parasitology (W.A.A.V.P.): Second edition of guidelines for evaluating the efficacy of anthelmintics in ruminants (bovine, ovine, caprine) Vet. Parasitol. 1995;58:181–213. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(95)00806-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolaston R.R. Selection of Merino sheep for increased and decreased resistance to Haemonchus contortus: periparturient effects on faecal egg counts. Int. J. Parasitol. 1992;22:947–953. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(92)90052-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolaston R.R., Barger I.A., Piper L.R. Response to helminth infection of sheep selected for resistance to Haemonchus contortus. Int. J. Parasitol. 1990;20:1015–1018. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(90)90043-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolaston R.R., Baker R.L. Prospects of breeding small ruminants for resistance to internal parasites. Int. J. Parasitol. 1996;26:845–855. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(96)80054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajac A.M., Herd R.P., McClure K.E. Trichostrongylid parasite populations in pregnant or lactating and unmated Florida Native and Dorset/Rambouillet ewes. Int. J. Parasitol. 1988;18:981–985. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(88)90181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaros L.G., Neves M.R.M., Benvenuti C.L., Navarro A.M.C., Sider L.H., Coutinho L.L., Vieira L.S. Response of resistant and susceptible Brazilian Somalis crossbreed sheep naturally infected by Haemonchus contortus. Parasitol. Res. 2014;113:1155–1161. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3753-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]