Abstract

Ubiquitination is a fundamental post-translational modification that regulates almost all aspects of cellular signalling and is ultimately catalysed by the action of E3 ubiquitin ligases. The RING-between-RING (RBR) family of E3 ligases encompasses 14 distinct human enzymes that are defined by a unique domain organisation and catalytic mechanism. Detailed characterisation of several RBR ligase family members in the last decade has revealed common structural and mechanistic features. At the same time these studies have highlighted critical differences with respect to autoinhibition, activation and catalysis. Importantly, the majority of RBR E3 ligases remain poorly studied, and thus the extent of diversity within the family remains unknown. In this mini-review we outline the current understanding of the RBR E3 mechanism, structure and regulation with a particular focus on recent findings and developments that will shape the field in coming years.

Keywords: enzyme activity, post-translational modification, RBR ubiquitin ligases, ubiquitin ligases, ubiquitin signalling

Introduction

The post-translational modification of proteins by addition of a single ubiquitin molecule (monoubiquitination) or a ubiquitin chain (polyubiquitination) is a fundamental process in eukaryotic biology which serves to regulate protein stability, activity, localisation and protein–protein interactions [1]. The specific nature of the ubiquitin modification determines the fate of the ubiquitinated substrate and the resulting downstream biological consequences. Ubiquitin itself can be ubiquitinated on eight distinct sites, leading to many possible homotypic (single linkage type) and heterotypic (multiple linkage types) polyubiquitin chain configurations with different biological functions [2]. Furthermore, ubiquitin may be subject to additional post-translation modifications (e.g. phosphorylation, acetylation), adding to the enormous diversity of the ubiquitin code [3].

The ubiquitination of protein substrates requires the sequential action of three enzymes: an E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme and an E3 ubiquitin ligase [4]. The substrate specificity and chain-type diversity in the ubiquitin system is encoded by the latter two enzymes, which catalyse the covalent attachment of the C-terminus of ubiquitin to the target protein. The E2 initially forms a thioester-linked intermediate with ubiquitin (E2∼Ub), and the E3 facilitates transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a reactive group in the substrate, typically the side chain of a lysine residue (although other modifications are possible).

The E3 ligases are subdivided into three families: RING, HECT and RING-between-RING (RBR), depending on domain architecture and the mechanism of ubiquitin transfer from E2 to the substrate [7]. The RING E3s are by far the most abundant of the human E3 ubiquitin ligases (∼600 members), followed by HECTs (28 members) and RBRs (14 members, Figure 1) [8]. RING E3s recruit E2∼Ub via their RING domain and facilitate direct attack of the thioester by the substrate nucleophile (aminolysis). HECT E3s utilise a two-step process in which ubiquitin is initially transferred from the E2∼Ub to a catalytic cysteine in the HECT domain (transthiolation). This E3∼Ub intermediate then reacts with a substrate nucleophile in the second step. RBR E3s utilise a ‘RING/HECT hybrid’ mechanism [9]. The RBR RING1 domain binds the E2 (of the E2∼Ub conjugate) in a RING E3-like fashion. Subsequent transthiolation to a conserved catalytic cysteine in the RING2 domain forms a reactive HECT-like E3∼Ub thioester intermediate which facilitates transfer of ubiquitin to the substrate. Despite these mechanistic similarities, the thioester forming HECT and RING2 domains are structurally unrelated.

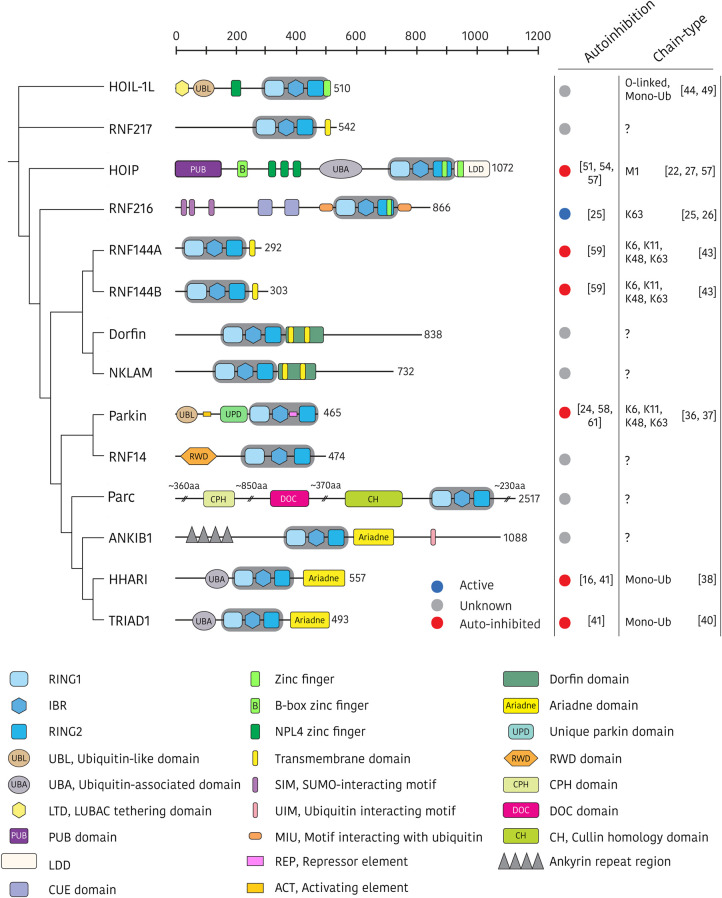

Figure 1. Phylogenetic relationships and structural domain architecture of the human RBR E3 ligases.

All family members contain a conserved RING1–IBR–RING2 (RBR) core (shaded in grey), and annotated ancillary domains. Domains are approximately to scale and annotated according to Uniprot [5] and Pfam [6] databases (accessed 25/05/2020), and literature search. The autoinhibition status and chain-type specificity of each RBR E3 ligase is summarised in the right-hand panels. Domain acronyms: CPH = domain that is conserved in Cul7, PARC, and HERC2 protein, CUE = Coupling of ubiquitin conjugation to ER degradation, DOC = APC10/DOC, LDD = linear ubiquitin chain determining domain, PUB = PNGase/UBA or UBX-containing proteins, RWD = RING finger and WD-domain-containing-proteins and DEAD-like helicases.

The RBR E3s are intriguing enzymes of ancient origin that regulate many important biological processes across eukaryotic phyla. For example, homologs of the RBR E3s HHARI and RNF14 are found in the fission yeast S. pombe (dbl4 and itt1, respectively), thus pointing to a fundamental biological role of these two enzymes. Indeed, the conserved RBR signature evolved before the divergence of plants and animals, more than a billion years ago [8,10]. Individually, the RBR E3s display remarkable functional diversity in terms of substrate selectivity, cellular localisation, ubiquitin chain-type specificity and regulatory mechanisms. Furthermore, several RBR E3s are implicated in the pathogenesis of human disease including Parkinson's disease, dementia, inflammation and cancer, and may represent unique targets for therapeutic intervention [11–13].

Nearly 10 years have passed since the hybrid catalytic mechanism of RBR E3 ligases was first described [9], and the field continues to evolve at pace. In this mini-review we provide an update on the current understanding of RBR E3 mechanism, structure and regulation, with a particular focus on recent findings which extend, and in some cases diverge from, established principles.

Catalytic mechanism of RBR E3 ligases

The RBR E3 ligases are complex multi-domain proteins, however all family members share a structurally conserved catalytic ‘RBR’ module of three consecutive zinc binding domains (Figure 1). These include a RING1 domain with a canonical RING fold, followed by an ‘in-between RING’ (IBR) domain, and finally a RING2 domain containing the catalytic cysteine. Despite nomenclature, the RING2 domain does not adopt a RING fold, but instead is structurally related to the IBR [14]. The linking sequences that connect RING1 and IBR, and IBR and RING2 are sufficiently flexible to permit large scale conformational rearrangements that are required for transitioning between autoinhibited and active forms as shown for several well characterised family members including HOIP, HHARI and parkin [15–18]. This inter-domain flexibility is also required for the correct alignment of the reaction complex components to facilitate transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to the RING2 active site cysteine and then the substrate [15,17,18].

RBR E3s typically exist in autoinhibited states which require controlled activation via distinct mechanisms to suppress off-target or excessive ubiquitination. Furthermore, ubiquitin/ubiquitin-like molecules are emerging as important modulators of RBR E3 activity, binding at allosteric sites and stabilising active conformations (see Autoinhibition and allosteric activation). In an activated state, the RBR can recruit an E2∼Ub via the RING1 domain (Figure 2). Many RBR E3s are able to function with multiple E2 partners in vitro, although physiological pairings remain largely unexplored [14]. Importantly, the RING1 interaction stabilises the E2∼Ub in an ‘open’ conformation which favours transthiolation to the RING2 active site cysteine, over reaction with nearby lysine residues, a critical mechanistic distinction between RBR and RING E3 ligases [17,19–21]. The RBR E2/E3 transfer complex has been observed structurally in a HOIP/UbcH5B∼Ub complex, which shows the E2∼Ub thioester positioned within catalytic proximity of the RING2 active site cysteine [17]. Overlap between the E2∼Ub and acceptor ubiquitin binding sites in HOIP [17,22] indicate that after the transthiolation reaction, the discharged E2 must dissociate from the E3 before acceptor ubiquitin can bind.

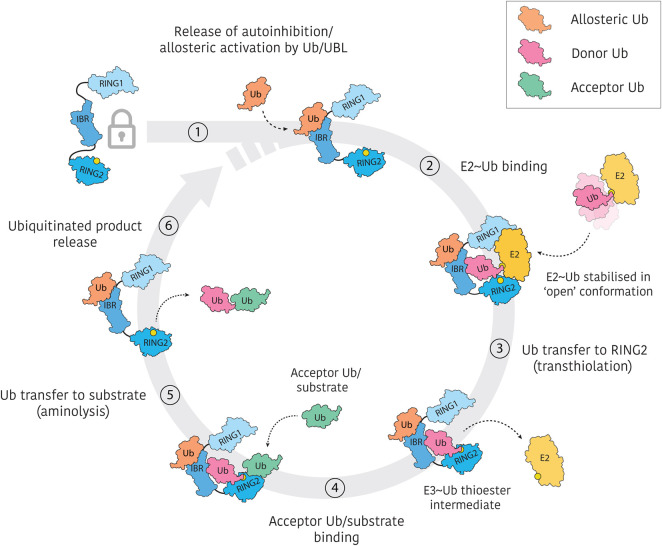

Figure 2. Generalised catalytic cycle of RBR E3 ligases.

RBR E3s typically exist in autoinhibited forms which require activation by distinct mechanisms. Furthermore, allosteric activation by ubiquitin or ubiquitin-like molecules appears to be a common feature of the RBR activation process. Active RBR E3s recruit E2∼Ub thioester intermediates via RING1 interactions and stabilise ‘open’ E2∼Ub conformations. Ubiquitin is then transferred from E2 to the RING2 active site cysteine (yellow circle) in an obligate transthiolation reaction. The resulting E3∼Ub thioester is reactive to nucleophilic attack by bound substrate (or acceptor ubiquitin as shown here). Release of the ubiquitinated substrate permits binding of another E2∼Ub, restarting the ubiquitination cycle.

While the process described above implies formation of a binary complex of RBR E3 and E2∼Ub, an alternate model has been proposed in which cooperative dimerisation of RBRs allows transfer of ubiquitin in trans from the E2∼Ub bound to one RBR molecule to the RING2 domain of another [23]. Both HOIP and parkin, however, have been shown to function as monomers, and complementation mutants are not able to rescue activity, thus supporting a model of ubiquitin transfer that is not dependent on RBR dimerisation [15,17,18]. Importantly, recent hydrogen–deuterium exchange mass-spectrometry (HDX-MS) experiments indicate large-scale domain motions as would be required for alignment of the bound E2∼Ub and RING2 active site within the same molecule [15,18].

In any case, the resulting E3∼Ub thioester is a short-lived species and therefore difficult to capture experimentally, however the crystal structure of a HOIP fragment with ubiquitin molecules non-covalently bound at both donor and acceptor sites provides a close surrogate for the final reaction intermediate (Figure 3A) [22]. This structure clearly demonstrates how the substrate nucleophile (in this instance, the N-terminal amino group of ubiquitin) is oriented for reaction with the E3∼Ub thioester.

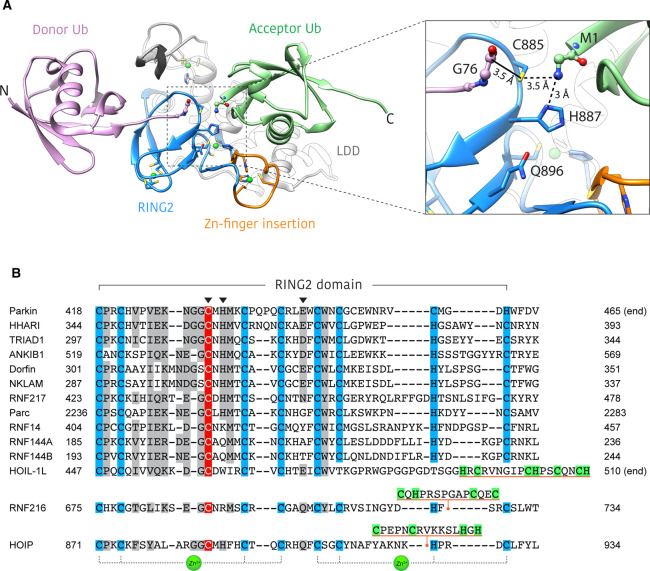

Figure 3. Structural basis for ubiquitin linkage specificity in HOIP.

(A) Structure of HOIP RING2-LDD/ubiquitin complex (PDB: 4LJO) [22]. The HOIP RING2-LDD (blue and white) orients the donor ubiquitin (purple) and acceptor ubiquitin (green) in such a way as to align the N and C-termini for M1 linkage formation. The unique RING2 zinc-finger insert (orange) forms part of the acceptor ubiquitin binding platform. Inset shows an enlarged view of the active site, highlighting the proximity of donor ubiquitin C-terminus, RING2 active site cysteine and the acceptor ubiquitin M1-amino group. The solid black line represents the E3∼Ub thioester bond that is not present in this structure. Residues of the RING2 catalytic triad are shown as blue sticks. (B) Alignment of human RBR RING2 domain sequences. Conserved zinc coordinating residues = blue, conservatively replaced residues = grey, active site cysteine = red. Catalytic triad residues are denoted by an arrowhead. Unique RING2 inserts for HOIP, HOIL-1L and RNF216 are underlined orange, with putative zinc binding residues highlighted green. The last three zinc coordinating residues of the HOIL-1L RING2 are not aligned with other family members, as the identity of these residues is currently unknown.

Structures of the RING2 active sites of HOIP, HHARI and parkin reveal a conserved cysteine, histidine, glutamate/glutamine catalytic triad (Figure 3). While the active site cysteine is essential for RBR function, the role of the non-cysteine active site residues appears to differ between family members [16,17,22]. Mutation of the HOIP active site histidine (H887A) renders the enzyme unable to form ubiquitin chains, but does not impair formation of the E3∼Ub thioester (transthiolation) and thus is important only for the aminolysis step of catalysis [17,22]. While similar observations have been made for HHARI [16], the equivalent mutation in parkin (H433A) impedes both transthiolation and aminolysis [24]. Notably, the catalytic triad residues are not completely conserved across all RBR ligases (Figure 3B). RNF216, for example, is an active E3 ligase despite lacking the active site histidine (Figure 3B) [25,26]. Together, these observations suggest that alternate active site configurations and catalytic mechanisms exist within the RBR family.

Determinants of ubiquitin chain-type specificity

Polyubiquitin chain formation results from the ligation of the C-terminal carboxyl of the donor ubiquitin with one of eight amino groups present in the acceptor ubiquitin (the N-terminal amino group of M1 or the side chains of K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63). The specific amino group selected for modification determines the chain linkage type, and thus the fate of the ubiquitinated substrate. In general, it is accepted that the last thioester-forming enzyme in the ubiquitin cascade dictates the specificity of the polyubiquitin linkage type. In the case of RING E3 ligases, this implies the associated E2 is responsible for specifying the chain linkage type, while thioester forming HECT and RBR E3s determine chain specificity themselves.

At present, our knowledge of the polyubiquitin chain types formed by RBR E3s is limited to a handful of examples. Even less well understood is the structural basis by which RBRs select certain amino groups for modification and not others. HOIP, the catalytic E3 component of the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC), is the only current exception and is well known to exclusively assemble M1-linked (also referred to as ‘linear’) ubiquitin chains [27]. This specificity arises from the C-terminal ‘linear ubiquitin chain determining domain’ (LDD), which, in concert with the RING2 domain, orients the N-terminal (M1) amino group of acceptor ubiquitin within catalytic proximity of the donor ubiquitin C-terminus (Figure 3A) [22]. Interestingly, the HOIP RING2 domain contains an additional zinc finger insertion which forms part of the acceptor ubiquitin binding platform and is important for M1-linked chain synthesis (Figure 3).

Recently, RNF216 (TRIAD3) has been shown to form free K63-linked ubiquitin chains in vitro, making it only the second RBR to exhibit preference for a single chain type [25,26]. This contrasts with previous studies which had implicated RNF216 in the proteasomal degradation of substrates via K48-linked polyubiquitination [28–34]. In these original studies however, K48 ubiquitination was typically inferred by increased K48 modification of substrates in response to RNF216 overexpression, without evidence of direct K48 ubiquitination by RNF216. It is possible that RNF216 or one of its K63 modified substrates regulates the activity of unidentified K48-specific E3 ligases. The structural basis for RNF216 K63 chain specificity is unknown, although a minimal construct consisting of only the RBR and C-terminal MIU-like domain retains the linkage specificity of the full-length enzyme [25]. It is of particular interest to note the presence of an additional zinc-finger-like insert between the last two zinc-binding residues of the RING2 domain (Figure 3) [25,35]. It will be interesting to see if this insert plays a similar role to the zinc-finger insert in the RING2 of HOIP which helps orient the acceptor ubiquitin for linkage specific reaction with the donor ubiquitin (Figure 3).

Unlike HOIP and RNF216, parkin does not exhibit specificity for a single chain type, but is able to assemble K6, K11, K48 and K63-linked chain types in vitro, and on depolarised mitochondria where parkin functions to trigger mitophagy [36]. In this context, the primary role of parkin appears to be bulk modification of outer mitochondrial membrane proteins with monoubiquitin and short chains, rather than long chain assembly [37].

HHARI, and its closely related homolog TRIAD1 (35% identity), are different again, as they are thought to monoubiquitinate the substrates of Cullin-RING ligases (CRLs), thus priming them for elongation by associated CRLs and their cognate E2s, i.e. Cdc34 (UBE2R1) which generates K48-linked chains [38–41]. The resulting chain architecture is therefore the product of interplay between multiple E2 and E3 enzymes, highlighting the inherent complexity of the ubiquitin system.

The advent of novel molecular tools for the detection of specific chain types coupled with the increased availability of powerful proteomic technologies, such as absolute quantification mass-spectrometry (AQUA-MS) [42] and ‘ubiquitin-clipping’ [37] now permits the study of previously undetectable chain types and architectures in vitro and in vivo, including the products of previously uncharacterised RBR E3 ligases. RNF144A and RNF144B are closely related proteins (54% identity) and the smallest members of the RBR family, consisting of only the RBR core and a C-terminal transmembrane domain (Figure 1). Using K6 and K33/K11 linkage specific affimers and AQUA-MS, Michel et al. [43] demonstrated that RNF144A and RNF144B, in combination with the E2 UbcH7 (UBE2L3), assemble K6, K11, K48 and K63-linked chains in vitro, the same combination of linkage types assembled by parkin.

Recently, HOIL-1L was reported to monoubiquitinate itself and a number of cellular substrates via esterification of serine and threonine residues [44]. This non-conventional O-linked ubiquitin modification was shown to be resistant to deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that cleave typical ubiquitin isopeptide bonds, but sensitive to hydroxylamine which readily cleaves ester bonds. Non-lysine ubiquitination has been observed previously [45–48], however this is the first report of an RBR E3 ligase generating these unique linkage types. These findings were partly confirmed by Fuseya et al. [49] who more recently describe that HOIL-1L attaches O-linked ubiquitin to HOIP and SHARPIN, but, interestingly, ubiquitinates itself on lysine residues. While these discrepancies need further investigation, HOIL-1L and O-linked ubiquitin appear to be important regulators of LUBAC activity. Notably, the HOIL-1L sequence contains an unusual RING2 extension with a number of potential zinc binding residues (Figure 3). The presence of an additional zinc binding site here is untested to the best of our knowledge but may provide a functionality unique to HOIL-1L, and its ability to form atypical ubiquitin linkages.

Based on the above examples, it is interesting to speculate about the common determinants of chain-type specificity (or lack thereof) in the RBR family. It may be that RBR modules alone are unable to specify a particular linkage type, but that specificity is encoded by the additional C-terminal structural elements incorporated into the RING2 domain (e.g. zinc fingers, ubiquitin interaction motifs), as is known to be the case for HOIP.

Ancillary ubiquitin binding domains

Outside of the RBR core, many RBR ligases contain protein–protein interaction domains including domains/motifs that bind to ubiquitin or ubiquitin-like molecules (Figure 1). These domains act to regulate RBR function by, for example, localising the E3 to ubiquitinated substrates or cofactors.

HOIP contains a ubiquitin-associated domain (UBA) N-terminal of the RBR core. UBA domains are small (∼45 amino acid) three-helix bundles that typically bind ubiquitin via the canonical hydrophobic surface centred on Ile44 [50]. Interestingly, the HOIP UBA does not bind ubiquitin [27], but instead interacts with ubiquitin-like (UBL) domains from other LUBAC subunits HOIL-1L and SHARPIN, which release autoinhibition of HOIP [51–54]. Recently the parkin coregulated gene (PACRG) product was identified as a novel LUBAC component, which interacts with LUBAC via the HOIP UBA and can functionally compensate for loss of SHARPIN from the complex [55]. As PACRG does not have a UBL, it is unclear how this interaction occurs, and whether PACRG represents an additional LUBAC component or replaces one of the cofactors HOIL-1L or SHARPIN in specific sub-complexes.

Bioinformatic analysis of RNF216 has revealed a number of cryptic binding domains for ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like molecules [25]. These include a consecutive pair of ‘Coupling of ubiquitin conjugation to ER degradation’ (CUE) domains (Figure 1). These predicted three-helix bundles are structurally related to UBA domains and contain ubiquitin binding motifs conserved in ubiquitin binding proteins of protein trafficking and degradation pathways [56]. The RNF216 CUE domains interact with K48, K63 and M1-linked polyubiquitin chains [25]. Mutation of three conserved CUE domain residues abrogated this function without affecting E3 activity or linkage specificity in vitro [25]. These observations suggest the CUE domains represent a non-catalytic ubiquitin binding site for RNF216 and may facilitate localisation to ubiquitinated substrates or cofactors.

The same study predicted the presence of two MIU-like ubiquitin interaction motifs flanking the RNF216 RBR core [25]. Unlike the previously described UBA and CUE domains, these motifs consist of a single helix only, but similarly interact with the canonical Ile44 ubiquitin surface. Curiously, the MIU downstream of the RNF216 RING2 appears to be critical for E3 ligase activity, although its molecular basis remains unclear [25,26]. The unstructured N-terminus of RNF216 also houses three SUMO-interaction motifs (SIMs), which are able to bind SUMO2 chains in vitro [25]. RNF216 does not ubiquitinate SUMO2 chains in vitro, suggesting the SIMs may instead function to localise RNF216 to SUMOylated substrates for ubiquitination at a distinct site [25].

Additional to the examples described here, many RBR E3s contain one or more ubiquitin interacting domains, as summarised in Figure 1. The physiological role of ubiquitin binding domains/motifs remains unknown in most cases although it is anticipated that these domains will play important roles in substrate recognition and recruitment.

Autoinhibition and allosteric activation

In general, RBR E3 ligases are thought to exist in autoinhibited forms, in which inhibitory domains from outside of the RBR core act to suppress ubiquitination activity. This appears to be the case at least to some extent for parkin, HOIP, HHARI, TRIAD1, RNF114A and RNF114B (Figure 1) [16,41,57–59]. Many of the crystal structures solved to date have captured these enzymes in stable autoinhibited states [16,24,60,61], and as such autoinhibition is now considered one of the defining features of the RBR family [62,63].

The mechanism of autoinhibition and activation is best understood for parkin, and multiple crystal structures have captured the protein in various states of activation [15,18,23,24,58,60,61,64,65]. In its inactive form, the unique parkin domain (UPD, also termed RING0 domain) masks the RING2 active site cysteine, while the ubiquitin-like domain (UBL) and repressor (REP) element block the E2 binding site on the RING1 domain (Figure 4) [24,60,61]. Parkin is activated by the mitochondrial outer membrane kinase PINK1, which phosphorylates Ser65 of both ubiquitin and the N-terminal ubiquitin-like (UBL) domain of parkin [64,65]. Integrative structural biology approaches combining crystal structures, HDX-MS and NMR have been used to illuminate the process of PINK1 dependent parkin activation in remarkable detail, tracking domain movements throughout the activation process [15,18,66].

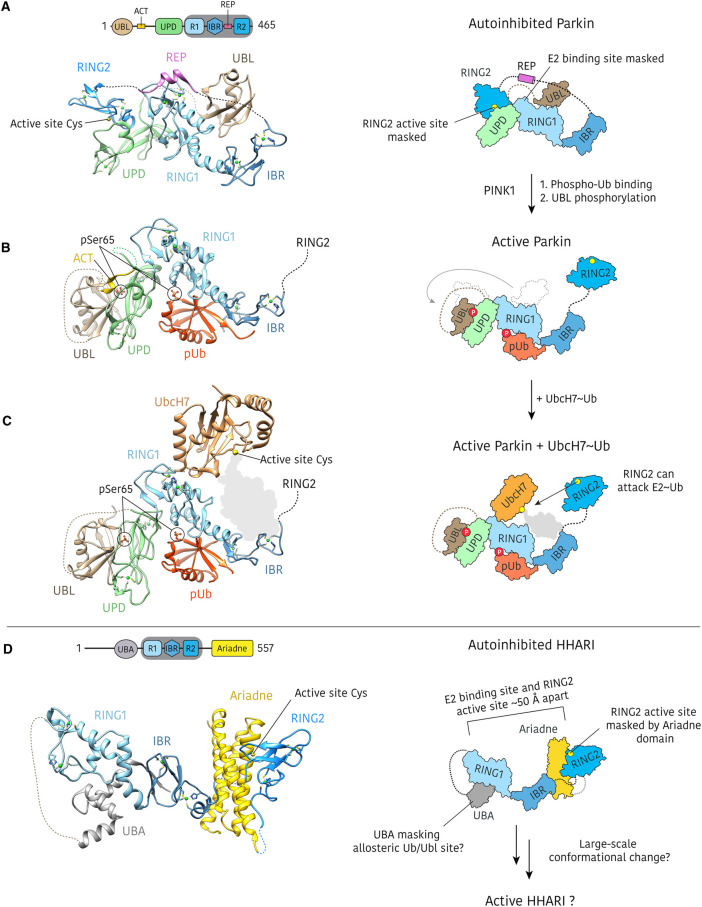

Figure 4. Parkin activation process and HHARI autoinhibition.

(A) Crystal structure of autoinhibited rat parkin (PDB: 4K95) in which the RING2 domain is bound to the UPD, and the E2 binding site on the RING1 domain is masked by the REP element and the UBL [61]. (B) Structure of active human parkin (PDB: 6GLC) showing binding of phospho-ubiquitin (pUb) and re-organisation of the UBL domain, which binds to the UPD when phosphorylated [15]. The displaced RING2 domain was omitted from the crystallisation construct. (C) Structure of active fruit fly (Bactrocera dorsalis) parkin with N-terminal UbcH7 fusion (PDB: 6DJW) [18]. The UbcH7 orientation is such that conjugated ubiquitin (represented here by a grey shadow) could be accommodated and is accessible by the mobile RING2 domain. The RING2 domain was omitted from the crystallisation construct and the UbcH7 molecule is contributed from a distinct polypeptide within the crystal lattice. (D) Crystal structure of autoinhibited HHARI (PDB: 4KBL) in which the Ariadne domain blocks access to the active site in the RING2 domain [16]. The E2 binding site and the RING2 active site are separated by more than 50 Å and the HHARI UBA blocks the putative allosteric activation site.

PINK1 phosphorylated ubiquitin (phospho-ubiquitin) binds to an allosteric site in the RING1/IBR domains of parkin and the resulting conformational change in the IBR leads to release of the UBL from RING1, exposing the E2∼Ub binding site, although the protein remains inactive. Release of the UBL is a prerequisite for subsequent phosphorylation of the UBL by PINK1. Finally, phospho-UBL binding to the UPD displaces the bound RING2 domain, making it accessible for transthiolation. A previously unresolved section of the UBL-UPD linker, termed the ‘activating element’ (ACT), was shown to be important for stabilisation of active parkin, by masking a hydrophobic groove exposed on the UPD surface following release of the RING2 domain [15]. In the ‘active’ parkin crystal structures, the liberated RING2 domain is either unresolved in electron density, or omitted from the crystallisation construct [15,18].

This activation process requires large scale domain motions that have been visualised by HDX-MS [15,18,66]. Most notable is rearrangement of the UBL, which moves >50 Å between inhibited and active forms (Figure 4). Dramatic conformational rearrangements may not be unique to parkin, however. HHARI is autoinhibited through occlusion of the RING2 active site cysteine by the C-terminal Ariadne domain [16]. The mechanism of activation remains poorly understood and to date there is no available structure of HHARI in an active conformation, however structures of the inactive complex show the E2 binding site and the HHARI active site are separated by more than 50 Å (Figure 4) [16,20,21].

HOIP, the catalytic component of the LUBAC, displays only weak ubiquitination activity in vitro but is activated by interaction with LUBAC cofactors HOIL-1L and SHARPIN [51–54]. Additionally, truncated HOIP constructs lacking the inhibitory UBA domain are fully active [54,57]. The structure of HOIP RBR in complex with UbcH5B∼Ub represents an active transfer complex, with E2 and E3 catalytic centres ideally oriented for transthiolation [17]. Interestingly, in this structure an additional ‘allosteric’ ubiquitin molecule is bound to the RING1/IBR in an equivalent position to that of the activating phospho-ubiquitin in parkin [64]. Binding of ubiquitin at this site appears to promote structural rearrangements required for efficient binding of the E2∼Ub donor ubiquitin. Furthermore M1-linked di-ubiquitin promotes HOIP∼Ub thioester and polyubiquitin chain formation [17]. Given M1-linked chains are a product of LUBAC activity, this allosteric activation may represent a positive-feedback loop. The extent to which allosteric activation by ubiquitin or ubiquitin-like molecules occurs across the RBR family is an interesting area for future prospecting.

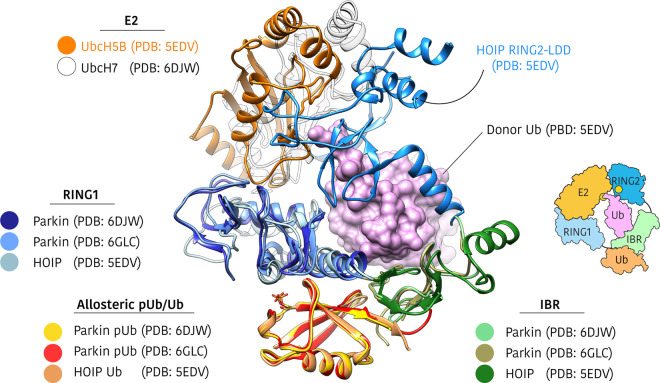

Alignment of active structures of HOIP and parkin reveals remarkable similarity in conformation of the resolved RING1 and IBR domains and conservation of the allosteric ubiquitin/phospho-ubiquitin binding site (Figure 5). The E2 binding mode is similar in active structures of HOIP and parkin, suggesting the parkin RING2 could accommodate E2∼Ub in a similar manner to HOIP (Figure 5). Furthermore, Kumar et al. [23] identified a cryptic ubiquitin binding site in the RING1–IBR of phospho-ubiquitin-bound Parkin. This ubiquitin binding site is equivalent to the HOIP donor ubiquitin site and points toward a common active conformation of RBR E3s.

Figure 5. Comparison of active parkin and HOIP structures.

Active parkin (PDB: 6GLC, 6DJW) and HOIP (PDB: 5EDV) structures were aligned by overlaying allosteric ubiquitin/phospho-ubiquitin molecules [15,17,18]. The UBL and UPD domains of parkin have been omitted for clarity. Parkin and HOIP show remarkably similar conformations of RING1 (blue) and IBR (green) domains and the HOIP-bound UbcH5B∼Ub shows how the donor ubiquitin (purple surface) is accommodated by the RING1–IBR. Allosteric ubiquitin/phospho-ubiquitin is bound at a common site, opposite the donor ubiquitin binding site. The RING2 domain in the HOIP structure is contributed from a second molecule in the crystal lattice, although the biologically relevant complex is thought to consist of a single RBR chain [17].

Finally, autoinhibition, while prevalent in the RBR family, may not be a true hallmark of these enzymes. Full length RNF216 for example, shows comparable in vitro activity to a minimal construct consisting of the RBR core and C-terminal MIU [25]. Detailed exploration of currently overlooked family members will reveal the generality of autoinhibition as a defining characteristic of the RBR family.

Summary and future directions

To date, the structure, function and regulation of RBRs have been investigated in exceptional detail for several family members, providing a comprehensive understanding of autoinhibition, activation and catalytic mechanism, particularly with respect to E2∼Ub recognition and transthiolation steps. The subsequent transfer of ubiquitin from E3∼Ub to the substrate is less well understood, and future studies will likely focus on deciphering the way in which RBRs recruit and orient substrates for selective ubiquitination with specific chain-types. While the biochemistry races ahead, our understanding of biology lags behind, hampered by the difficulty in identifying bona fide physiological substrates and cofactors which often only interact weakly and transiently with the ubiquitination machinery, and may not coexist under basal conditions. A multi-faceted approach using modern proteomics to expand the observable RBR interactome and targeted modulation of activity, either genetically or pharmacologically (see Box 1) will be central to unravelling the precise roles of RBR E3s in biology.

Box 1: Targeting RBR E3s with small molecules

There is considerable interest in the development of small molecule modulators of RBR E3 activity as chemical tools for dissecting RBR signalling pathways, and for therapeutic applications. Covalent inhibitors that irreversibly modify the active site cysteine and inhibit activity have been developed for HOIP, and in principle this approach could be extended to other RBR E3s [67–70]. Structure-guided inhibitor design permits rational optimisation of hit compounds, although crystallisation of RBRs is often hampered by inherent interdomain flexibility. To this end, single domain antibody binders of HOIP have been successfully employed as crystallisation chaperones to facilitate reproducible crystallisation [71]. In addition, stapled peptides that block interactions between the different LUBAC components and inhibit LUBAC activity have been described [52,72,73]. It will be interesting to see if other RBR ligases can also be inhibited by blocking their interaction with specific cofactors and if this feat can be achieved by more drug-like small molecules.

Certain parkin variants are linked to autosomal-recessive juvenile Parkinson's disease [11]. These variants are unable to be activated by PINK1 phosphorylation, which results in impaired parkin-dependent mitophagy, a process required to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis [11]. In this context, selective activation of parkin using small molecules may have therapeutic value [60,61,64,65]. A deep understanding of the molecular basis of parkin activation, afforded to us by almost a decade of research, will be fundamental to these efforts.

Finally, the recent boom in ‘targeted degradation’ as a new therapeutic modality has spurred on the hunt for novel E3 ligases which can be pharmacologically re-directed to degrade pathogenic targets [74,75]. Whether the RBR family harbours any fit for purpose degradative ligases remains to be seen, but in a proof of concept study, an active (truncated) parkin construct was shown to induce degradation of model substrates [76]. The strict regulation of RBRs may reduce their general utility in targeted degradation, but on the other hand this may provide a unique opportunity for the development of highly selective protein degraders.

The remarkable structural and functional diversity that exists, even within a limited subset of well-studied RBRs, highlights the need for exploratory work on the remaining, less well-characterised family members. There are almost certainly undiscovered features which will challenge established principles.

Perspectives

The RBR E3s are an intriguing family of E3 ubiquitin ligases which are characterised by a unique catalytic mechanism and strict regulation of ubiquitination activity. RBR E3s regulate a diverse range of biological processes and have important roles in the pathogenesis of human disease.

RBR E3s share a conserved structural core of zinc binding domains and a common highly regulated catalytic mechanism that proceeds via an obligate E3-ubiquitin thioester intermediate. However, our understanding of the RBR E3 structure and function comes from only a small set of family members and the extent of functional diversity remains unknown.

The future of RBR research will likely focus on understanding the precise role of these enzymes in biological pathways, which will become more tractable with modern methodologies in proteomics and access to high quality chemical probes. Extending our understanding of overlooked family members will be critical for establishing the true hallmarks of the RBR family.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all members of the Lechtenberg lab, Melissa Compagnoni and David Komander for comments on the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ACT

Activating element

- AQUA-MS

Absolute quantification mass spectrometry

- E2∼Ub

E2-ubiquitin thioester intermediate

- HDX-MS

Hydrogen–deuterium exchange mass spectrometry

- HECT

Homologous to E6-AP carboxyl terminus

- HHARI

Human homolog of Ariadne

- HOIL-1L

Heme-oxidised IRP2 ubiquitin ligase 1

- HOIP

HOIL-1-interacting protein

- LDD

Linear ubiquitin chain determining domain

- LUBAC

Linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- PACRG

Parkin-coregulated gene

- PINK1

PTEN-induced kinase 1

- RBR

RING-between-RING

- REP

Repressor element

- RING

Really Interesting New Gene

- RNF216

RING finger protein 216

- SHARPIN

Shank-associated RH domain-interacting protein

- SUMO

Small ubiquitin-related modifier

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

Research in the Lechtenberg lab is supported by WEHI start-up funding and the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia (Ideas Grants GNT1182757, GNT1186575).

Open Access

Open access for this article was enabled by the participation of Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in an all-inclusive Read & Publish pilot with Portland Press and the Biochemical Society under a transformative agreement with CAUL.

Author Contribution

T.R.C. and B.C.L. wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hershko A. and Ciechanover A. (1998) The ubiquitin system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 425–479 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komander D. and Rape M. (2012) The ubiquitin code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 203–229 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060310-170328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swatek K.N. and Komander D. (2016) Ubiquitin modifications. Cell Res. 26, 399–422 10.1038/cr.2016.39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deol K.K., Lorenz S. and Strieter E.R. (2019) Enzymatic logic of ubiquitin chain assembly. Front. Physiol. 10, 835 10.3389/fphys.2019.00835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UniProt C. (2019) Uniprot: a worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D506–D515 10.1093/nar/gky1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Gebali S., Mistry J., Bateman A., Eddy S.R., Luciani A., Potter S.C. et al. (2019) The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D427–DD32 10.1093/nar/gky995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berndsen C.E. and Wolberger C. (2014) New insights into ubiquitin E3 ligase mechanism. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 301–307 10.1038/nsmb.2780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marin I., Lucas J.I., Gradilla A.C. and Ferrus A. (2004) Parkin and relatives: the RBR family of ubiquitin ligases. Physiol. Genomics 17, 253–263 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00226.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wenzel D.M., Lissounov A., Brzovic P.S. and Klevit R.E. (2011) UBCH7 reactivity profile reveals parkin and HHARI to be RING/HECT hybrids. Nature 474, 105–108 10.1038/nature09966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marin I. and Ferrus A. (2002) Comparative genomics of the RBR family, including the Parkinson's disease-related gene parkin and the genes of the ariadne subfamily. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19, 2039–2050 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pickrell A.M. and Youle R.J. (2015) The roles of PINK1, parkin, and mitochondrial fidelity in Parkinson's disease. Neuron 85, 257–273 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Margolin D.H., Kousi M., Chan Y.M., Lim E.T., Schmahmann J.D., Hadjivassiliou M. et al. (2013) Ataxia, dementia, and hypogonadotropism caused by disordered ubiquitination. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 1992–2003 10.1056/NEJMoa1215993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rittinger K. and Ikeda F. (2017) Linear ubiquitin chains: enzymes, mechanisms and biology. Open Biol. 7, 170026 10.1098/rsob.170026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spratt D.E., Walden H. and Shaw G.S. (2014) RBR e3 ubiquitin ligases: new structures, new insights, new questions. Biochem. J. 458, 421–437 10.1042/BJ20140006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gladkova C., Maslen S.L., Skehel J.M. and Komander D. (2018) Mechanism of parkin activation by PINK1. Nature 559, 410–414 10.1038/s41586-018-0224-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duda D.M., Olszewski J.L., Schuermann J.P., Kurinov I., Miller D.J., Nourse A. et al. (2013) Structure of HHARI, a RING-IBR-RING ubiquitin ligase: autoinhibition of an Ariadne-family E3 and insights into ligation mechanism. Structure 21, 1030–1041 10.1016/j.str.2013.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lechtenberg B.C., Rajput A., Sanishvili R., Dobaczewska M.K., Ware C.F., Mace P.D. et al. (2016) Structure of a HOIP/E2∼ubiquitin complex reveals RBR E3 ligase mechanism and regulation. Nature 529, 546–550 10.1038/nature16511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sauvé V., Sung G., Soya N., Kozlov G., Blaimschein N., Miotto L.S. et al. (2018) Mechanism of parkin activation by phosphorylation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 623–630 10.1038/s41594-018-0088-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dove K.K., Stieglitz B., Duncan E.D., Rittinger K. and Klevit R.E. (2016) Molecular insights into RBR E3 ligase ubiquitin transfer mechanisms. EMBO Rep. 17, 1221–1235 10.15252/embr.201642641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dove K.K., Olszewski J.L., Martino L., Duda D.M., Wu X.S., Miller D.J. et al. (2017) Structural studies of HHARI/UbcH7∼Ub reveal unique E2∼Ub conformational restriction by RBR RING1. Structure 25, 890–900.e5 10.1016/j.str.2017.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan L., Lv Z., Atkison J.H. and Olsen S.K. (2017) Structural insights into the mechanism and E2 specificity of the RBR E3 ubiquitin ligase HHARI. Nat. Commun. 8, 211 10.1038/s41467-017-00272-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stieglitz B., Rana R.R., Koliopoulos M.G., Morris-Davies A.C., Schaeffer V., Christodoulou E. et al. (2013) Structural basis for ligase-specific conjugation of linear ubiquitin chains by HOIP. Nature 503, 422–426 10.1038/nature12638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar A., Chaugule V.K., Condos T.E.C., Barber K.R., Johnson C., Toth R. et al. (2017) Parkin-phosphoubiquitin complex reveals cryptic ubiquitin-binding site required for RBR ligase activity. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 24, 475–483 10.1038/nsmb.3400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wauer T. and Komander D. (2013) Structure of the human Parkin ligase domain in an autoinhibited state. EMBO J. 32, 2099–2112 10.1038/emboj.2013.125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seenivasan R., Hermanns T., Blyszcz T., Lammers M., Praefcke G.J.K. and Hofmann K. (2019) Mechanism and chain specificity of RNF216/TRIAD3, the ubiquitin ligase mutated in Gordon Holmes syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 28, 2862–2873 10.1093/hmg/ddz098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwintzer L., Aguado Roca E. and Broemer M. (2019) TRIAD3/RNF216 e3 ligase specifically synthesises K63-linked ubiquitin chains and is inactivated by mutations associated with Gordon Holmes syndrome. Cell Death Discov. 5 10.1038/s41420-019-0158-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirisako T., Kamei K., Murata S., Kato M., Fukumoto H., Kanie M. et al. (2006) A ubiquitin ligase complex assembles linear polyubiquitin chains. EMBO J. 25, 4877–4887 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakhaei P., Mesplede T., Solis M., Sun Q., Zhao T., Yang L. et al. (2009) The E3 ubiquitin ligase Triad3A negatively regulates the RIG-I/MAVS signaling pathway by targeting TRAF3 for degradation. PLoS Pathog. 5, 1–14 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu C., Feng K., Zhao X., Huang S., Cheng Y., Qian L. et al. (2014) Regulation of autophagy by E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF216 through BECN1 ubiquitination. Autophagy 10, 2239–2250 10.4161/15548627.2014.981792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chuang T.H. and Ulevitch R.J. (2004) Triad3a, an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase regulating Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 5, 495–502 10.1038/ni1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fearns C., Pan Q., Mathison J.C. and Chuang T.H. (2006) Triad3a regulates ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of RIP1 following disruption of Hsp90 binding. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 34592–34600 10.1074/jbc.M604019200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mabb A.M., Je H.S., Wall M.J., Robinson C.G., Larsen R.S., Qiang Y. et al. (2014) Triad3a regulates synaptic strength by ubiquitination of Arc. Neuron 82, 1299–1316 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alturki N.A., McComb S., Ariana A., Rijal D., Korneluk R.G., Sun S.C. et al. (2018) Triad3a induces the degradation of early necrosome to limit RipK1-dependent cytokine production and necroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 9, 592 10.1038/s41419-018-0672-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Z., Yu G., Liu Z., Zhu J., Chen C., Liu R.E. et al. (2018) Paeoniflorin inhibits glioblastoma growth in vivo and in vitro: a role for the Triad3A-dependent ubiquitin proteasome pathway in TLR4 degradation. Cancer Manag. Res. 10, 887–897 10.2147/CMAR.S160292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martino L., Brown N.R., Masino L., Esposito D. and Rittinger K. (2018) Determinants of E2-ubiquitin conjugate recognition by RBR E3 ligases. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–13 10.1038/s41598-017-18513-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ordureau A., Sarraf S.A., Duda D.M., Heo J.M., Jedrychowski M.P., Sviderskiy V.O. et al. (2014) Quantitative proteomics reveal a feedforward mechanism for mitochondrial PARKIN translocation and ubiquitin chain synthesis. Mol. Cell 56, 360–375 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swatek K.N., Usher J.L., Kueck A.F., Gladkova C., Mevissen T.E.T., Pruneda J.N. et al. (2019) Insights into ubiquitin chain architecture using Ub-clipping. Nature 572, 533–537 10.1038/s41586-019-1482-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scott D.C., Rhee D.Y., Duda D.M., Kelsall I.R., Olszewski J.L., Paulo J.A. et al. (2016) Two distinct types of E3 ligases work in unison to regulate substrate ubiquitylation. Cell 166, 1198–214.e24 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stewart M.D., Ritterhoff T., Klevit R.E. and Brzovic P.S. (2016) E2 enzymes: more than just middle men. Cell Res. 26, 423–440 10.1038/cr.2016.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelsall I.R., Kristariyanto Y.A., Knebel A., Wood N.T., Kulathu Y. and Alpi A.F. (2019) Coupled monoubiquitylation of the co-E3 ligase DCNL1 by Ariadne-RBR E3 ubiquitin ligases promotes cullin-RING ligase complex remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 2651–2664 10.1074/jbc.RA118.005861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelsall I.R., Duda D.M., Olszewski J.L., Hofmann K., Knebel A., Langevin F. et al. (2013) TRIAD1 and HHARI bind to and are activated by distinct neddylated Cullin-RING ligase complexes. EMBO J. 32, 2848–2860 10.1038/emboj.2013.209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirkpatrick D.S., Gerber S.A. and Gygi S.P. (2005) The absolute quantification strategy: a general procedure for the quantification of proteins and post-translational modifications. Methods 35, 265–273 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michel M.A., Swatek K.N., Hospenthal M.K. and Komander D. (2017) Ubiquitin linkage-specific affimers reveal insights into K6-linked ubiquitin signaling. Mol. Cell 68, 233–46 e5 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelsall I.R., Zhang J., Knebel A., Arthur S.J.C. and Cohen P. (2019) The E3 ligase HOIL-1 catalyses ester bond formation between ubiquitin and components of the Myddosome in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 13293–8 10.1073/pnas.1905873116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pao K.C., Wood N.T., Knebel A., Rafie K., Stanley M., Mabbitt P.D. et al. (2018) Activity-based E3 ligase profiling uncovers an E3 ligase with esterification activity. Nature 556, 381–385 10.1038/s41586-018-0026-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shimizu Y., Okuda-Shimizu Y. and Hendershot L.M. (2010) Ubiquitylation of an ERAD substrate occurs on multiple types of amino acids. Mol. Cell 40, 917–926 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang X., Herr R.A. and Hansen T.H. (2012) Ubiquitination of substrates by esterification. Traffic 13, 19–24 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01269.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cadwell K. and Coscoy L. (2005) Ubiquitination on nonlysine residues by a viral E3 ubiquitin ligase. Science 309, 127–130 10.1126/science.1110340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fuseya Y., Fujita H., Kim M., Ohtake F., Nishide A., Sasaki K. et al. (2020) The HOIL-1L ligase modulates immune signalling and cell death via monoubiquitination of LUBAC. Nat. Cell Biol. 22, 663–673 10.1038/s41556-020-0517-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hurley J.H., Lee S. and Prag G. (2006) Ubiquitin-binding domains. Biochem. J. 399, 361–372 10.1042/BJ20061138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yagi H., Ishimoto K., Hiromoto T., Fujita H., Mizushima T., Uekusa Y. et al. (2012) A non-canonical UBA-UBL interaction forms the linear-ubiquitin-chain assembly complex. EMBO Rep. 13, 462–468 10.1038/embor.2012.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fujita H., Tokunaga A., Shimizu S., Whiting A.L., Aguilar-Alonso F., Takagi K. et al. (2018) Cooperative domain formation by homologous motifs in HOIL-1L and SHARPIN plays a crucial role in LUBAC stabilization. Cell Rep. 23, 1192–1204 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu J., Wang Y., Gong Y., Fu T., Hu S., Zhou Z. et al. (2017) Structural insights into SHARPIN-mediated activation of HOIP for the linear ubiquitin chain assembly. Cell Rep. 21, 27–36 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stieglitz B., Morris-Davies A.C., Koliopoulos M.G., Christodoulou E. and Rittinger K. (2012) LUBAC synthesizes linear ubiquitin chains via a thioester intermediate. EMBO Rep. 13, 840–846 10.1038/embor.2012.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meschede J., Sadic M., Furthmann N., Miedema T., Sehr D.A., Muller-Rischart A.K. et al. (2020) The parkin-coregulated gene product PACRG promotes TNF signaling by stabilizing LUBAC. Sci. Signal. 13, eaav1256 10.1126/scisignal.aav1256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prag G., Misra S., Jones E.A., Ghirlando R., Davies B.A., Horazdovsky B.F. et al. (2003) Mechanism of ubiquitin recognition by the CUE domain of Vps9p. Cell 113, 609–620 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00364-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smit J.J., Monteferrario D., Noordermeer S.M., van Dijk W.J., van der Reijden B.A. and Sixma T.K. (2012) The E3 ligase HOIP specifies linear ubiquitin chain assembly through its RING-IBR-RING domain and the unique LDD extension. EMBO J. 31, 3833–3844 10.1038/emboj.2012.217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chaugule V.K., Burchell L., Barber K.R., Sidhu A., Leslie S.J., Shaw G.S. et al. (2011) Autoregulation of Parkin activity through its ubiquitin-like domain. EMBO J. 30, 2853–2867 10.1038/emboj.2011.204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ho S.R., Lee Y.J. and Lin W.C. (2015) Regulation of RNF144A E3 ubiquitin ligase activity by self-association through its transmembrane domain. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 23026–23038 10.1074/jbc.M115.645499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Riley B.E., Lougheed J.C., Callaway K., Velasquez M., Brecht E., Nguyen L. et al. (2013) Structure and function of Parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase reveals aspects of RING and HECT ligases. Nat. Commun. 4, 1982 10.1038/ncomms2982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trempe J.F., Sauve V., Grenier K., Seirafi M., Tang M.Y., Menade M. et al. (2013) Structure of parkin reveals mechanisms for ubiquitin ligase activation. Science 340, 1451–1455 10.1126/science.1237908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walden H. and Rittinger K. (2018) RBR ligase-mediated ubiquitin transfer: a tale with many twists and turns. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 440–445 10.1038/s41594-018-0063-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dove K.K. and Klevit R.E. (2017) RING-Between-RING E3 ligases: emerging themes amid the variations. J. Mol. Biol. 429, 3363–3375 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wauer T., Simicek M., Schubert A. and Komander D. (2015) Mechanism of phospho-ubiquitin-induced PARKIN activation. Nature 524, 370–374 10.1038/nature14879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kumar A., Aguirre J.D., Condos T.E.C., Martinez-Torres R.J., Chaugule V.K., Toth R. et al. (2015) Disruption of the autoinhibited state primes the E3 ligase parkin for activation and catalysis. EMBO J. 34, 2506–2521 10.15252/embj.201592337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Condos T.E.C., Dunkerley K.M., Freeman E.A., Barber K.R., Aguirre J.D., Chaugule V.K. et al. (2018) Synergistic recruitment of UbcH7∼Ub and phosphorylated Ubl domain triggers parkin activation. EMBO J. 37, 1–16 10.15252/embj.201798099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Johansson H., Tsai Y.C.I., Fantom K., Chung C.W., Kümper S., Martino L. et al. (2020) Fragment-based covalent ligand screening enables rapid discovery of inhibitors for the RBR E3 ubiquitin ligase HOIP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 2703–2712 10.1021/jacs.8b13193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oikawa D., Sato Y., Ohtake F., Komakura K., Hanada K., Sugawara K. et al. (2020) Molecular bases for HOIPINs-mediated inhibition of LUBAC and innate immune responses. Commun. Biol. 3, 163 10.1038/s42003-020-0882-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Katsuya K., Hori Y., Oikawa D., Yamamoto T., Umetani K., Urashima T. et al. (2018) High-throughput screening for linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC) selective inhibitors using homogenous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF)-based assay system. SLAS Discov. 23, 1018–1029 10.1177/2472555218793066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Katsuya K., Oikawa D., Iio K., Obika S., Hori Y., Urashima T. et al. (2019) Small-molecule inhibitors of linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC), HOIPINs, suppress NF-kappaB signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 509, 700–706 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.12.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsai Y.C.I., Johansson H., Dixon D., Martin S., Cw C., Clarkson J. et al. (2020) Single-domain antibodies as crystallization chaperones to enable structure-based inhibitor development for RBR E3 ubiquitin ligases. Cell Chem. Biol. 27, 83–93.e9 10.1016/j.chembiol.2019.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aguilar-Alonso F., Whiting A.L., Kim Y.J. and Bernal F. (2018) Biophysical and biological evaluation of optimized stapled peptide inhibitors of the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 26, 1179–1188 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.11.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang Y., Schmitz R., Mitala J., Whiting A., Xiao W., Ceribelli M. et al. (2014) Essential role of the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex in lymphoma revealed by rare germline polymorphisms. Cancer Discov. 4, 480–493 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pettersson M. and Crews C.M. (2019) PROteolysis TArgeting chimeras (PROTACs): past, present and future. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 31, 15–27 10.1016/j.ddtec.2019.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schapira M., Calabrese M.F., Bullock A.N. and Crews C.M. (2019) Targeted protein degradation: expanding the toolbox. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 949–963 10.1038/s41573-019-0047-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ottis P., Toure M., Cromm P.M., Ko E., Gustafson J.L. and Crews C.M. (2017) Assessing different E3 ligases for small molecule induced protein ubiquitination and degradation. ACS Chem. Biol. 12, 2570–2578 10.1021/acschembio.7b00485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]