Abstract

Objective To compare the plantar pressure distribution and the kinematics of the rearfoot on the stance phase of subjects with or without patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS).

Methods A total of 26 subjects with PFPS and 31 clinically healthy subjects, who were paired regarding age, height and mass, participated in the study. The plantar pressure distribution (peak pressure) was assessed in six plantar regions, as well as the kinematics of the rearfoot (maximum eversion angle, percentage of the stance phase when the maximum angle was reached, and percentage of the stance phase in which the rearfoot was in eversion). The data were analyzed by descriptive and inferential statistics, with a significance level of p ≤ 0.05.

Results The pressure on the six plantar regions analyzed and the magnitude of the maximum eversion angle of the rearfoot when walking on flat surfaces did not present differences among the subjects with PFPS. However, the PFPS subjects showed, when walking, an earlier maximum eversion angle of the rearfoot than the subjects on the control group, and stayed less time with the rearfoot in eversion.

Conclusion The PFPS seems to be related to modifications on the temporal pattern on the kinematics of the rearfoot.

Keywords: patellofemoral pain syndrome, biomechanical phenomena, knee, gait

Introduction

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is characterized by diffuse anterior knee pain, usually of insidious onset and slow progression; 1 it accounts for 25% of all injuries that affect this joint. 2 Among the many factors involved in its multifactorial etiology, patellar misalignment, quadriceps weakness, 1 changes in lower limb postural alignment, especially those regarding the rearfoot angle, 2 3 in addition to abnormalities in the biomechanics of the lower extremity, stand out.

Barton et al 4 state that knowledge of the kinematic differences between individuals with and without PFPS is important for health professionals and researchers, for it is necessary to develop and optimize strategies for prevention and treatment for PFPS. A kinematic change, such as greater rearfoot eversion, may lead to compensatory internal rotation of the femur, and may cause greater compression between the patellar joint surface and the lateral femoral condyle, and lead to patellofemoral symptoms. 5

Additionally, Santos 6 reports that there is a direct positive relationship between the maximum rearfoot eversion angle and the plantar pressure distribution, that is, as the values of the maximum angle of the rearfoot eversion increase, the plantar pressure in the midfoot regions also increase. Thus, we hypothesized that subjects with PFPS will present a greater maximum angle of rearfoot eversion during the gait, and that this alteration could cause changes in plantar pressure distribution, with higher values for the peak pressure in the medial regions of the foot.

Whereas plantar pressure distribution has a great potential to predict abnormal movements during locomotion, 6 it is important to evaluate its characteristics during the performance of functional activities in subjects with PFPS, since it is during these activities that these subjects most exacerbate their symptoms. In addition, an assessment of plantar pressure distribution could add foundations for the rehabilitation of PFPS, helping to elucidate the behavior of the foot interface with the floor or footwear as a reflection of the dynamic alignment of the lower limbs. 7

According to Thijs et al, 1 changes in the distribution of plantar pressure may reduce the shock-absorbing function of the foot, causing some of the ground reaction force to be transferred to the proximal joints, including the knee, resulting in an overload on the patellofemoral joint, which could lead to patellofemoral pain.

Although there are studies in the literature on plantar pressure distribution, so far only four have been performed in subjects with PFPS. Thijs et al 1 8 evaluated plantar pressure in order to determine the risk factors for the development of PFPS in military personnel and runners respectively. Aliberti et al 7 9 analyzed the plantar pressure distribution in subjects with PFPS during stair descent and walking respectively. However, the results found by these authors differ in relation to the patterns of plantar pressure distribution presented by the subjects, which may have occurred because the studies were conducted with different populations, different instruments, and in different situations. In addition, to date no studies have been found evaluating plantar pressure distribution and rearfoot kinematics in subjects with concomitant PFPS.

Given the aforementioned information, the present study aimed to compare the distribution of plantar pressure and kinematics of the rearfoot during the gait stance phase in subjects with and without PFPS.

Methods

The present study included 57 subjects, who were divided into 2 groups: the patellofemoral pain syndrome group (PFPSG), which was composed of 26 subjects with 23 ± 6 years, 59.8 ± 8.1 kg and 1.65 ± 0.07 m of height, and the control group (CG), which was composed of 31 clinically healthy subjects, with 21 ± 4 years, 59.1 ± 8.1 kg, and 1.64 ± 0.05 m of height. The groups were paired regarding age ( p = 0.308), mass ( p = 0.724) and height ( p = 0.519). All participants signed the informed consent form, which was approved by the local Ethics in Research Committee (protocol no. 33/2010).

The inclusion criteria for the PFPSG were subjects who had anterior or retropatellar pain, exacerbated by at least three of the following situations: climbing or descending stairs, squatting for a long time, kneeling, running, sitting for long periods, and playing sports; insidious onset of symptoms unrelated to a traumatic event; pain ≥ 2 cm on the Visual Numerical Scale (VNS, which goes from 0 cm to 10 cm) in the patellofemoral joint in the 7 days preceding the test; pain, of any magnitude, in 2 functional tests lasting 30 seconds each (squatting at 90 degrees and descending a 25-cm-high step). 10

The inclusion criteria for the CG were: no history of meniscal or ligament injury, trauma, surgery or lower limb fracture; no history of knee or patellofemoral joint pain (0 cm of pain on the VNS) 11 ; absence of any hip and foot joint problems, neurological or musculoskeletal system diseases; not having been submitted to physiotherapeutic treatment on the lower limb; no pain of any magnitude during the 30-second functional tests (squatting at 90 degrees and descending a 25-cm-high step). 10

The exclusion criteria for both groups were history of lower limb trauma, meniscal or ligamentous knee injury; 10 recurrent patellar dislocation; and history of knee or lower limb surgery. 11

The evaluation of plantar pressure distribution was performed using the Pedar-X in-shoe pressure measuring system (Novel GmbH Inc., Munich, Germany), with an acquisition frequency of 100 Hz. All insoles were calibrated according to manufacturer's specifications. All subjects wore a standard shoe (Moleca flats, Calçados Beira Rio SA, Novo Hamburgo, RS, Brazil). The insoles were placed inside the shoes and connected to a conditioner inserted in a belt fixed to the subjects' waist. This conditioner communicated and transferred the data to the computer by Bluetooth, thus facilitating the movement of the subject about the place of the evaluations.

To evaluate the rearfoot kinematics, a digital video camera was used (HandyCam DCR-SR65, Sony, Minato, Tokyo, Japan), which was placed on a tripod at a height of 50 cm from the ground and a distance of 3 m from the subject, with images acquired in the posterior frontal plane of the subject, with an acquisition frequency of 60 Hz.

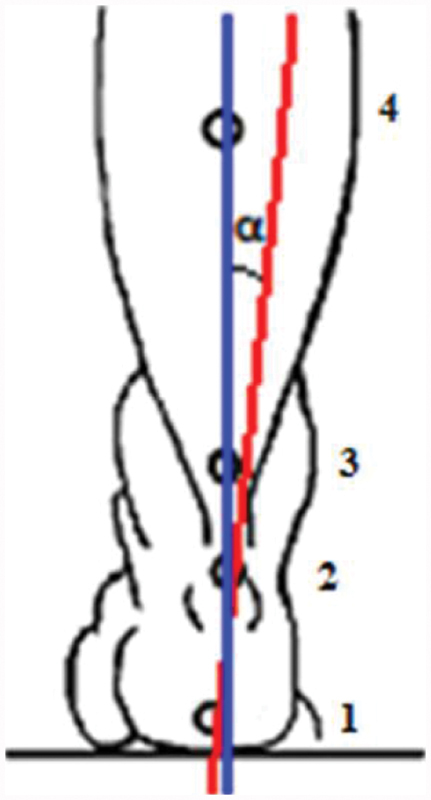

Four spherical markers were placed on the subjects at the following anatomical points: a marker at the center of the heel, just above the sole of the flat shoe (1), another at the center of the heel, at the insertion of the Achilles tendon (2), a third at the center of the Achilles tendon, at the height of the medial malleolus (3), and a fourth 15 cm above the third marker, at the center of the leg (4) 6 12 13 ( Figure 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Position of the markers for the calculation of the rearfoot angle: 1) just above the flat shoe sole; 2) center of the heel, at the insertion of the Achilles tendon; 3) center of the Achilles tendon, at the height of the medial malleolus; 4) 15 cm above the third marker, at the center of the leg.

The subjects were instructed to walk along a distance of 8 m during 5 attempts. Gait speed was monitored but not controlled. No differences between the groups regarding gait speed were observed ( p = 0.7).

To calculate the actual coordinates, a two-dimensional calibration system was placed in the filming area. This calibrator consisted of 8 points, with dimensions of 61 cm on the x axis and 80 cm on the y axis, and a fixed point positioned next to the calibrator.

Data Processing

Distribution of Plantar Pressure

For the analysis of plantar pressure distribution data, the initial and final 1.5 meter of walking were discarded, as well as the first and last steps, to avoid the effect of movement acceleration and deceleration. An average of 10 steps per subject were analyzed.

The plantar surface was divided into medial rearfoot, central rearfoot, lateral rearfoot, medial forefoot, lateral forefoot, 7 and midfoot ( Figure 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Foot divided into six regions according to the mask applied. Abbreviations: CR, central rearfoot; LF, lateral forefoot; LR, lateral rearfoot; M, midfoot; MF, medial forefoot; MR, medial rearfoot.

Peak pressure (kPa) was analyzed in the 6 plantar areas that were adjusted via software proportionally to the foot width and length of each subject.

Kinematics

For the kinematic analysis of the rearfoot, five steps were analyzed. 14 15 16 To estimate foot pronation during gait, the eversion angle of the rearfoot was used. 6 17 18 The digitalization of the images was performed using the Ariel Performance Analysis System (APAS, Ariel Dynamics Inc., Trabuco Canyon, CA, US) and the data were digitally filtered with a 6-Hz cutoff frequency. The maximum value of the rearfoot eversion angle was analyzed during the gait stance phase and the percentage of the stance phase in which the angle was reached. This angle was defined by the intersection of the lines that form the leg segment with the foot segment ( Figure 1 ). Eversion was considered positive, and inversion, negative. The stance phase of the gait was considered from the moment in which the heel touches the ground until the detachment of the toes.

The kinematic data were normalized on a time basis, which was adjusted from 0% to 100% for the support phase of the gait, with 1% intervals using the heel touch instant (0%) as reference, until the toes detach from the ground (100%). Normalization was performed by a routine in the Matrix Laboratory (MATLAB, MathWorks, Natick, MA, US) software. Data from the limb with patellofemoral joint pain of the PFPSG were analyzed, and in cases of bilateral dysfunction, the limb with the highest pain intensity was considered. In the CG, the dominant limb data were analyzed, which was determined by the limb that the subjects used to kick a ball. 19

Statistical analysis

For the statistical analysis, we used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, US) software, version 17.0, and descriptive statistics was used to characterize the subjects. The Shapiro-Wilk test evidenced plantar and kinematic pressure data with Gaussian distribution. The independent t test was used to test the homogeneity of the subjects (age, mass, height and walking speed), to compare the maximum value of the rearfoot angle during the stance phase of the gait on a flat surface, the percentage of the gait stance phase at which this angle was reached by the PFPSG and CG, and the percentage of the gait stance phase that each group remained with the foot in eversion. 2 × 6 analysis of variance (ANOVA; 2 groups x 6 plantar regions, with the 6 plantar regions considered as repeated measures) was used to compare the peak pressure (kPa) in the 6 plantar regions between the PFPSG and CG. The level of significance adopted was of p ≤ 0.05.

Results

No group effect was observed (F = 0.30; p = 0.58), nor any interaction between the groups and plantar regions (F = 0.66; p = 0.65) at peak pressure (kPa) during the gait on a flat surface ( Figure 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Mean and standard deviations of the peak pressure (kPa) in the six plantar regions of both groups during the flat surface gait.

No significant differences were found between subjects with and without PFPS in the magnitude of the maximum rearfoot eversion angle in the stance phase during the gait on a flat surface. However, the PFPSG reached the maximum eversion angle of the rearfoot earlier ( p = 0.01) during the stance phase (32.56 ± 22.11%) compared to the CG (46.14 ± 18.02%), and, consequently, remained a lower percentage of the gait stance phase with the foot in eversion ( p = 0.04) (PFPSG: 33.90 ± 21.76%; CG: 46.48 ± 18.21) ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations and 95% confidence interval of the maximum rearfoot angle of eversion, the percentage stance phase of the gait in which this angle was reached, and the percentage at which the foot remained in eversion in the study groups during flat surface walking.

| PFPSG ( n = 23) | CG ( n = 28) | p -value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | 95%CI | Mean ± SD | 95%CI | ||

| Maximum angle of rearfoot eversion (degrees) | 11.38 ± 3.15 | 10.01–12.74 | 10.45 ± 2.54 | 9.30–11.51 | 0.25 |

| Percentage of the gait stance phase in which the maximum angle of rearfoot eversion was reached | 32.56 ± 22.11 | 23.00–42.13 | 46.14 ± 18.02 | 37.58–53.89 | 0.01* |

| Percentage of the gait stance phase in which the foot remained in eversion | 33.90 ± 21.76 | 24.26–43.55 | 46.48 ± 18.21 | 39.22–54.50 | 0.04* |

Abbreviations: 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CG, control group; PFPSG, patellofemoral pain syndrome group; SD, standard deviation.

Note: *Statistically significant difference.

Discussion

The evaluation of the plantar pressure distribution showed no differences between the groups regarding the peak pressure in the six plantar regions analyzed during the gait stance phase on a flat surface. Aliberti et al 7 analyzed the distribution of plantar pressure during the stance phase when walking down stairs in subjects with PFPS. However, these authors observed a medially-directed contact in the rearfoot and midfoot, as well as smaller plantar loads during the movement of walking down stairs in individuals with PFPS. The lower pressure peaks in these subjects when descending stairs were related to an attempt to reduce the patellofemoral joint reaction force, aiming to reduce the overload and, consequently, the pain.

In another study, Aliberti et al 9 evaluated the distribution of plantar pressure in three sub-phases of the gait stance (initial contact, mid stance and propulsion) in subjects with PFPS, observing a medially-directed initial contact in the rearfoot, and a more lateralized propulsion in the forefoot. According to them, the everted entry of the foot in the initial contact seems to have reduced the excursion of the initial pronation that must occur in this phase for the absorption of the load. Consequently, it showed an increase in the contact area in the lateral forefoot still in the mid stance, which culminated in a more lateral foot detachment and reduction in the peak pressure on the medial forefoot during propulsion.

Some methodological differences between the present study and those by Aliberti et al 7 9 could explain the conflicting findings between them. In our study, we chose to use standard shoes during gait (Moleca flats), because most of the daily functional activities are performed while wearing shoes. In the studies by Aliberti et al, 7 9 the subjects wore socks during the data collection. Additionally, the authors controlled the subjects' cadence and, consequently, their walking speed. In our study, we did not perform this control because we believe it could alter the gait pattern of the subjects. In the studies by Aliberti et al, 7 9 the sample consisted predominantly of women, but some men also participated. In our study, all participants were female. Additionally, Aliberti et al 9 analyzed the gait in the three stance subphases, which is different from our study, in which we assessed it as a whole.

Thijs et al, 1 when investigating the intrinsic risk factors for the development of PFPS in women, found the presence of three risk factors related to gait that could predispose the development of PFPS: a more lateralized pressure distribution at the initial foot contact, reduction of maximal pressure time in the fourth metatarsal, and a delay in the lateromedial center of pressure (COP) change in forefoot contact during the gait. According to the authors, these changes can cause a reduction in foot shock absorption, causing most of the ground reaction forces to be transferred to the proximal joints, among them, the knee, resulting in an overload on the patellofemoral joint and, consequently, on patellofemoral pain. However, these findings, although relevant, cannot be generalized to the entire population with PFPS or directly compared with the present study, since they were performed in a specific population (military personnel), and with a different instrument (FootScan pressure platform).

According to Santos, 6 in a study with normal subjects with an increase in the rearfoot eversion angle, there is a direct positive relationship between the maximum eversion angle of the rearfoot and the distribution of plantar pressure among the rearfoot regions (medial and lateral portions) and the midfoot (medial portion). In the groups with and without excessive eversion, the pattern of plantar pressure distribution and contact area in the plantar regions were similar, but always higher among the subjects with excessive eversion.

We hypothetized that subjects with PFPS would have a highter rearfoot eversion when walking in a flat surface compared to CG and that this could lead to changes in plantar pressure distribuition, with highter values for peak pressure in the medial regions of the foot. However, this hypothesis wasn’t confirmed throught the kinematic analysis of the rearfoot, it was found that both groups had excessive rearfoot eversion (PFPSG: 11,38° +/− 3,15°; CG: 10,45° +/− 2,54°), according Cheung e Ng 12 e Santos 6 classifications. Thus, we believe that the presence of this excessive eversion in PFPSG and CG could explain the similarity in plantar pressure distribuition between groups. The maximum rearfoot eversion angle during the stance phase gait in a flat surface showed no diferences between PFPSG and CG, corroborating the Levinger and Gilleard17 findings. However, there isn’t a consensus in the literature regarding angular values considered normal for the rearfoot eversion movement. 20 According to Cheung and Ng, 12 a rearfoot eversion angle greater than 6° may be considered excessive. Santos, 6 however, classifies a maximum rearfoot eversion angle of 8° or more as excessive eversion, and Cornwall and McPoil 21 consider angles greater than 10°. The values found by Santos 6 for the subjects with excessive eversion were similar (10.7°) to those found in both groups of our study, suggesting that our subjects could present feet with excessive eversion.

In the present study, we found that the increase in the rearfoot eversion angle was not related to the patellofemoral symptoms, as asymptomatic subjects also presented higher values for this angle, indicating that a more everted foot posture may not be related to the PFPS, confirming the findings of other authors. 17 18 22 In addition, Thijs et al 1 state that one must be careful when attributing the cause of the patellofemoral symptoms to an increase in eversion of the rearfoot.

However, this eversion can be considered abnormal not only if it is excessive considering the normal angular value required for locomotion, but also if it occurs in an inappropriate temporal pattern 2 within the gait cycle. An abnormal eversion time may disrupt the temporal sequence of lower extremity joint movements. 17 In the present study, the PFPSG reached the maximum angle of eversion of the rearfoot earlier in the course of the stance phase compared to the CG, evidencing that the subjects with PFPS performed a faster eversion of the rearfoot after contact of the heel with the ground than the control subjects. Consequently, we found that the subjects with PFPS spent less time with their feet in eversion during the gait stance phase than the CG subjects.

Moseley et al, 20 by analyzing the three-dimensional kinematics of the rearfoot during the gait stance phase of 14 healthy men, found a gradual eversion of the rearfoot from heel contact reaching a maximum of 7.3° at approximately 57% of the stance phase prior to heel elevation. In the present study, subjects with PFPS reached the maximum eversion angle of the rearfoot at 32.56%, and the control subjects, at 46.14% of the gait stance phase. Other studies have also found maximum eversion occurring earlier 18 23 within the gait cycle in subjects with PFPS compared to the CG. In contrast, other authors 17 reported that the maximum eversion occurred later in individuals with PFPS when compared to subjects without the syndrome.

Barton et al 18 also observed, in subjects with PFPS, a rearfoot eversion peak earlier in the gait cycle compared to subjects without the condition (32.7% versus 36.5% respectively). However, the authors point to the existence of great variability between individuals considering the time to reach the peak of this angle, attributing this variability to inconsistent findings between studies. Thus, they suggest the existence of subpopulations of individuals with PFPS with different behavioral patterns. Our findings also pointed to the existence of this variability (95% confidence interval [95%CI]: 23.00–42.13%), which could also suggest the existence of these subpopulations of individuals with PFPS. However, one should be cautious about this statement, because this variability was also observed among the control subjects in the present study (95%CI: 37.58–53.89%).

According to Barton et al, 18 23 the earlier eversion peak in the PFPSG may indicate faster eversion after heel contact and greater and faster knee and patellofemoral joint loads. The change in the temporal pattern of this movement could lead to asynchrony between knee flexion, eversion and internal tibial rotation. The knee would extend normally, but the foot and consequently the tibia would not reverse their actions. This situation may lead to a mismatch between femoral and tibial movements that would generate excessive stress and knee strain forces. Alternatively, this may result in hip and femur compensation, potentially increasing the risk of injury, such as PFPS, especially during running. 24 This early eversion peak in the PFPSG may have occurred in part by the foot structure of these subjects. Therefore, this relationship may be linked to the development of PFPS, indicating that a more pronated foot posture results in faster dynamic eversion in people who have risk factors for the development of PFPS. In the present study, because we have not evaluated the type of feet of the subjects, we cannot say whether the occurrence of early eversion peak is related or not to the types of foot (normal, pronated, or supinated).

On the other hand, Levinger and Gilleard 17 observed, in subjects with PFPS, the rearfoot eversion peak later in the gait stance phase compared to the CG (39% in the CG and 46% in the PFPSG). The delay in peak eversion may have been an attempt to attenuate the shock during the onset of the stance. However, the authors do not make it clear in their study whether the change in rearfoot motion in the PFPSG reflects a change in gait to avoid pain or an inherent cause factor.

We suggest conducting further studies to evaluate the kinematics during activities with greater functional demand, such as climbing and descending stairs and ramps, simultaneously evaluating the rearfoot and knee kinematics in order to verify if there really is a relationship between these movements and the development or aggravation of PFPS. In addition, future researches evaluating the speed of the rearfoot eversion movement and its impact on knee loads during gait in individuals with PFPS are necessary.

Conclusion

Subjects with PFPS showed a maximum angle of eversion earlier in the course of the stance phase than the CG subjects, which could lead to higher and faster patellofemoral joint loads and the development or aggravation of PFPS. This finding may be particularly important when considering treatment or prevention strategies for PFPS. Theoretically, the treatment strategies aim to reduce rearfoot eversion, but knowledge of temporal changes and their correction can have similar overall effects in lower limb mobility and, therefore, optimized clinical outcome.

Agradecimentos

Aos fisioterapeutas Marlon Francys Vidmar e Luiz Fernando Bortoluzzi de Oliveira, e ao professor do curso de Fisioterapia da Universidade de Passo Fundo (UPF), Gilnei Lopes Pimentel, pelo auxílio na coleta dos dados. Aos médicos César Antônio de Quadros Martins, André Kuhn, Osmar Valadão Lopes Junior, José Saggin e Paulo Renato Saggin, pelo encaminhamento das pacientes para a realização da pesquisa.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank physical therapists Marlon Francys Vidmar and Luiz Fernando Bortoluzzi de Oliveira, as well as the professor of the Physical Therapy course at Universidade de Passo Fundo (UPF), Gilnei Lopes Pimentel, for their support in data collection. We would also like to thank physicians César Antônio de Quadros Martins, André Kuhn, Osmar Valadão Lopes Junior, José Saggin and Paulo Renato Saggin for referring patients to our research.

Conflitos de Interesse Os autores declaram não haver conflito de interesses.

Trabalho desenvolvido no Laboratório de Postura e Equilíbrio do Centro de Ciências da Saúde e do Esporte da Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina (CEFID/UDESC) e no Laboratório de Biomecânica da Universidade de Passo Fundo (UPF).

Study developed at the Posture and Balance Laboratory, Centro de Ciências da Saúde e do Esporte da Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina (CEFID/UDESC) and at the Biomechanics Laboratory, Universidade de Passo Fundo (UPF).

Referências

- 1.Thijs Y, Van Tiggelen D, Roosen P, De Clercq D, Witvrouw E. A prospective study on gait-related intrinsic risk factors for patellofemoral pain. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17(06):437–445. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31815ac44f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powers C M, Maffucci R, Hampton S. Rearfoot posture in subjects with patellofemoral pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;22(04):155–160. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1995.22.4.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levinger P, Gilleard W.An evaluation of the rearfoot posture in individuals with patellofemoral pain syndrome J Sports Sci Med 20043(YISI 1):8–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barton C J, Levinger P, Menz H B, Webster K E. Kinematic gait characteristics associated with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic review. Gait Posture. 2009;30(04):405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2009.07.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiberio D. The effect of excessive subtalar joint pronation on patellofemoral mechanics: a theoretical model. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1987;9(04):160–165. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1987.9.4.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos J O.Aspectos cinemáticos e cinéticos do movimento de eversão do calcanhar durante a marcha [dissertação]Florianópolis: Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina;2008

- 7.Aliberti S, Costa M S, Passaro A C, Arnone A C, Sacco I C. Medial contact and smaller plantar loads characterize individuals with Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome during stair descent. Phys Ther Sport. 2010;11(01):30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thijs Y, De Clercq D, Roosen P, Witvrouw E. Gait-related intrinsic risk factors for patellofemoral pain in novice recreational runners. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42(06):466–471. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.046649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aliberti S, Costa M S, Passaro A C, Arnone A C, Hirata R, Sacco I C. Influence of patellofemoral pain syndrome on plantar pressure in the foot rollover process during gait. Clinics (São Paulo) 2011;66(03):367–372. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000300001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cowan S M, Bennell K L, Hodges P W. Therapeutic patellar taping changes the timing of vasti muscle activation in people with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Clin J Sport Med. 2002;12(06):339–347. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200211000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powers C M. Patellar kinematics, part I: the influence of vastus muscle activity in subjects with and without patellofemoral pain. Phys Ther. 2000;80(10):956–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung R T, Ng G Y. Efficacy of motion control shoes for reducing excessive rearfoot motion in fatigued runners. Phys Ther Sport. 2007;8:75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perry S D, Lafortune M A. Influences of inversion/eversion of the foot upon impact loading during locomotion. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 1995;10(05):253–257. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(95)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornwall M W, McPoil T G. Comparison of 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional rearfoot motion during walking. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 1995;10(01):36–40. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(95)90435-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chuter V H. Relationships between foot type and dynamic rearfoot frontal plane motion. J Foot Ankle Res. 2010;3(09):9. doi: 10.1186/1757-1146-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diss C E. The reliability of kinetic and kinematic variables used to analyse normal running gait. Gait Posture. 2001;14(02):98–103. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(01)00125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levinger P, Gilleard W. Tibia and rearfoot motion and ground reaction forces in subjects with patellofemoral pain syndrome during walking. Gait Posture. 2007;25(01):2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barton C J, Levinger P, Webster K E, Menz H B. Walking kinematics in individuals with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a case-control study. Gait Posture. 2011;33(02):286–291. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santos G M, Ries L GK, Sperandio F F, Say K G, Pulzatto F, Pedro V M. Tempo de início da atividade elétrica dos estabilizadores patelares na marcha em sujeitos com e sem síndrome de dor femoropatelar. Fisioter Mov. 2011;24(01):125–132. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moseley L, Smith R, Hunt A, Gant R. Three-dimensional kinematics of the rearfoot during the stance phase of walking in normal young adult males. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 1996;11(01):39–45. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(95)00036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cornwall M W, McPoil T G. Influence of rearfoot postural alignment on rearfoot motion during walking. Foot. 2004;14:133–138. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duffey M J, Martin D F, Cannon D W, Craven T, Messier S P. Etiologic factors associated with anterior knee pain in distance runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(11):1825–1832. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200011000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barton C J, Levinger P, Crossley K M, Webster K E, Menz H B. Relationships between the Foot Posture Index and foot kinematics during gait in individuals with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Foot Ankle Res. 2011;4(10):10. doi: 10.1186/1757-1146-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dierks T A, Davis I. Discrete and continuous joint coupling relationships in uninjured recreational runners. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2007;22(05):581–591. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]