Abstract

Aim: Coronary atherosclerotic plaques can be detected in asymptomatic subjects and are related to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) levels in patients with coronary artery disease. However, researchers have not yet determined the associations between various plaque characteristics and other lipid parameters, such as HDL-C and TG levels, in low-risk populations.

Methods: One thousand sixty-four non-diabetic subjects (age, 57.86 ± 9.73 years; 752 males) who underwent coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) were enrolled and the severity and patterns of atherosclerotic plaques were analyzed.

Results: Statin use was reported by 25% of the study population, and subjects with greater coronary plaque involvement (segment involvement score, SIS) were older and had a higher body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, unfavorable lipid profiles and comorbidities. After adjusting for comorbidities, only age (β = 0.085, p < 0.001), the male gender (β = 1.384, p < 0.001), BMI (β = 0.055, p = 0.019) and HbA1C levels (β = 0.894, p < 0.001) were independent factors predicting the greater coronary plaque involvement in non-diabetic subjects. In the analysis of significantly different (> 50%) stenosis plaque patterns, age (OR: 1.082, 95% CI: 10.47–1.118) and a former smoking status (OR: 2.061, 95% CI: 1.013–4.193) were independently associated with calcified plaques. For partial calcified (mixed type) plaques, only age (OR: 1.085, 95% CI: 1.052–1.119), the male gender (OR: 7.082, 95% CI: 2.638–19.018), HbA1C levels (OR: 2.074, 95% CI: 1.036–4.151), and current smoking status (OR: 1.848, 95% CI: 1.089–3.138) were independently associated with the risk of the presence of significant stenosis in mixed plaques.

Conclusions: A higher HbA1c levels is independently associated with the presence and severity of coronary artery atherosclerosis in non-diabetic subjects, even when LDL-C levels are tightly controlled.

Keywords: Atherosclerotic plaque, Coronary computed tomography angiography, High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Non-diabetic

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the main causes of an increased risk in mortality and morbidity, and the central component of the pathogenesis is atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is currently considered a chronic inflammatory process in the arteries that causes endothelial damage, atheroma formation, and vessel occlusion. Vulnerable plaque rupture is the first step in a myocardial infarction and plays a central role in pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. Therefore, the early detection of subclinical atherosclerosis can identify subjects at risk, and treatment must be initiated in a timely manner to prevent disease progression. Among the risk factors associated with CVD, diabetes mellitus (DM) is a well-known risk factor for cardiovascular events and is often accompanied by macrovascular complications1). According to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines 2019, diabetes should be treated as equivalent to CAD and statin treatments are recommended to control LDL-C levels2). The atherosclerotic process likely begins during the pre-diabetic stage3), suggesting that atherosclerosis begins very early and is still associated with some risk of developing adverse events, even in subjects without diabetes.

As shown in a recent study, subclinical atherosclerosis (plaque or coronary artery calcification) is detected in 49.7% of subjects without a cardiovascular risk factor (CVRF)4). In that study, serum LDL-C levels were independently associated with the presence and extent of subclinical atherosclerosis, even in CVRF-free subjects with an optimal LDL-C level, suggesting that the LDL-C level should be lowered to prevent atherosclerotic plaque formation and disease progression in low-risk subjects. Lipid-lowering therapy with statins now has been widely used to prevent atherosclerosis, and a high proportion of the population, even individuals without prior history of CVD, have already received statin therapy. Therefore, clinicians should determine whether other important risk factors are related to plaque progression, even if LDL-C levels are already tightly controlled. To our knowledge, the risk factors that contribute to atherosclerotic plaques in patients without diabetes have been investigated less frequently. Additionally, few studies have examined the relationships between different plaque characteristics and other lipid parameters, such as HDL-C and TG levels. Therefore, the aim of our current study is to investigate the risk factors contributing to atherosclerosis in the coronary artery and evaluate the relationships with various plaque characteristics in non-diabetic subjects.

Methods

This study employed a cross-sectional observational design. Participants who underwent coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) using 256-slice multidetector computed tomography as part of a general routine health evaluation at the Taipei Veterans General Hospital between December 2013 and May 2017 were invited to participate and screened. Only patients aged 30–79 years with no prior history of coronary artery disease, and non-diabetic subjects with a fasting glucose level < 126 mg/dL and HbA1C level < 6.5% were enrolled to evaluate the association between subclinical atherosclerosis and risk factors in study subjects. The associations between baseline characteristics, biochemical parameters, coronary atherosclerosis involvement and plaque patterns were analyzed. Hypertensive patients was defined subjects whose BP > 140/80 mmHg or underwent hypertensive medication treatment. Former smokers were defined as individuals who declared that they ceased smoking at least 6 months prior to the study. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital.

CCTA Measurement

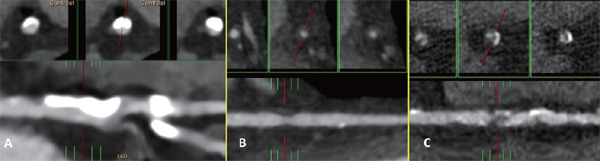

CCTA was performed using multiple detector computed tomography (Definition Flash, Siemens Healthier, Erlangen, Germany). Blood pressure and heart rate were measured before CCTA, and beta-blockers with or without a calcium channel blocker were administered to patients with an initial heart rate faster than 80 beats per minute analyzed with other scanners, if the patient had no contraindications, to achieve a heart rate of < 65 beats per minutes, respectively. Prospective electrocardiography-gated axial scans for calcium scoring were recorded at 75% of the R-R interval with the collimation set to 3.0 mm. The scanning sequence began approximately 1 cm above the left main coronary artery. CCTA parameters were 120 kV and 60 mA. A temporal resolution of 230 ms was achieved using the half-scan reconstruction method with a 350 ms gantry rotation time. The CCTA was performed using retrospective gated helical scanning, with parameters of 64 × 0.5 mm-128 × 0.625 mm collimation, a 270 ms-350 ms gantry rotation time, and 80–135 kV adapted to the body size. The bolus-tracking method was used after injecting 50–100 mL of iodinated contrast medium (Iopamiro370, Bracco Imaging SpA, Milan, Italy; Ultravist 370, Bayer Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany), based on the patient's body size, at a rate of 4.5–5.0 mL per second, followed by 50 mL of normal saline at a rate of 5.5 mL per second. The workstation automatically selected the best phase; if the image quality was suboptimal, we manually reconstructed a phase with the best possible image quality, which was reconstructed into images with a slice thickness of 0.75 mm and 0.9 mm at 0.45-mm intervals. The degree of coronary luminal stenosis were assessed based on established guidelines5). Furthermore, independent radiologist reviewed plaque morphology in current study and defined plaque morphology as calcified (pure calcified plaque), non-calcified (soft, no calcified plaque detected) and mixed (partial calcified and partial soft plaque) (Fig. 1). The coronary artery calcification (CAC) was calculated using the Agatston method and graded as follows: 0, 1–99, 100–399, and ≥ 400. Several CCTA parameters were measured, including CAC scores, segment involvement score (SIS), segment stenosis score (SSS) and atheroma burden obstructive score (ABOS)3). The SIS was calculated as the total number of coronary artery segments that contained plaques, regardless of the degree of luminal stenosis within each segment (minimum = 0; maximum = 16). The SSS was used to measure the overall extent of coronary artery plaques. Each individual coronary segment was graded as having no plaques to severe plaques (i.e., scores ranging from 0 to 3 points), based on the extent of coronary artery luminal diameter obstruction. The extent scores in all 16 individual segments were added to yield a total score that ranged from 0 to 48 points6, 7). The ABOS was defined as the number of plaques with > 50% stenosis in the entire coronary artery tree.

Fig. 1.

Longitudinal and cross sectional views of significant (> 50%) stentic calcified (A), non-calcified (soft)(B) and partial calcified (mixed) (C) in coronary artery

Laboratory Measurements

Blood samples were collected after an overnight fast. Serum biochemical parameters, including triglyceride, HDL-C, LDL-C, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), uric acid, fasting blood glucose, and HbA1c levels, were measured using a TBA-c16000 automatic analyzer (Toshiba Medical Systems, Tochigi, Japan). Biochemical parameters were measured using a previously described method8).

Statistical Analysis

All data are reported as frequencies (percentages) or means ± standard deviation (SD). All participants were divided into groups based on the presence of atherosclerotic plaque segment (SIS score). Because all study subjects were enrolled at our healthcare center, they were non-diabetic or had no prior history of CAD, and the coronary atherosclerosis was not severe. Therefore, we used SIS (1–16) to represent the degree of coronary plaque involvement. Parametric continuous data were compared between groups using a one-way analysis of variance. Categorical data were compared between groups using a Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate the independent factors related to the coronary plaque involvement. Regarding variable plaque characteristics and patterns, a plaque with > 50% stenosis was defined as significant stenosis and various plaque patterns, including calcified plaques, non-calcified plaque (soft) and partial calcified (mixed) plaques, were analyzed separately to investigate which parameters independently associated with the presence of various significant (> 50% stenosis) plaque morphology. The presence of specific type plaque is the binary outcome variables and odds ratios are calculated adjusted for possible confounding factors. The p-value was two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 15.0, SPSS Inc.).

Results

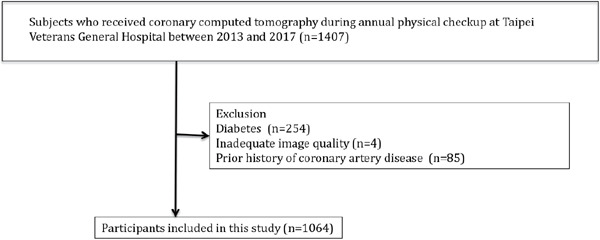

One thousand four hundred seven subjects were initially screened. After excluding 85 subjects with a prior history of coronary artery disease, 4 patients with unclear images and 254 patients with diabetes (Fig. 2), 1064 non-diabetic subjects (age, 57.86 ± 9.73 years; 752 males and 312 females) were enrolled in our study. Coronary artery plaques were observed in 546 (56.9 %) subjects, and Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study population, which were divided into groups with no atherosclerosis (SIS = 0), few (SIS= 1–2, n = 300) and multiple (SIS ≥ 3, n = 306) atherosclerotic plaques.

Fig. 2.

Study flow

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study subjects.

| SIS = 0 N = 458 |

SIS = 1or 2 N = 300 |

SIS ≥ 3 N = 306 |

P value | P for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 54.93 ± 9.72 | 58.45 ± 8.97 | 62.79 ± 8.56 | < .001 | < .001 |

| Male, n (%) | 266 (58.1) | 210 (70) | 276 (90.2) | < .001 | < .001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 85 (18.6) | 69 (23.1) | 82.92 (6.8) | 0.025 | 0.007 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 72 (15.7) | 102 (34.1) | 157 (51.3) | < .001 | < .001 |

| * Former smoker, n(%) | 32 (7) | 38 (12.7) | 36 (12) | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 93 (20.4) | 62 (20.7) | 79 (26.2) | < 0.05 | < 0.01 |

| Statin use, n (%) | 89 (19.4) | 76 (25.4) | 100 (32.7) | < .001 | < .001 |

| BMI, Kg/m2 | 24.17 ± 2.95 | 25.04 ± 3.31 | 25.71 ± 3.32 | < .001 | < .001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 120.38 ± 17.16 | 124.24 ± 15.65 | 127.81 ± 16.43 | < .001 | < .001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 76.80 ± 9.86 | 78.82 ± 9.78 | 79.71 ± 10.14 | < .001 | < .001 |

| LVEF, % | 61.79 ± 6.93 | 62.41 ± 6.77 | 62.95 ± 8.29 | 0.171 | 0.063 |

| Framingham 10-year risk20), % | 6.09 ± 6.00 | 9.40 ± 6.98 | 13.65 ± 7.23 | < .001 | < .001 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.61 ± 0.27 | 5.64 ± 0.29 | 5.77 ± 0.36 | < .001 | < .001 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 90.60 ± 8.55 | 90.91 ± 9.50 | 92.29 ± 9.34 | 0.034 | 0.011 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 83.09 ± 13.30 | 83.37 ± 14.16 | 79.41 ± 15.26 | < .001 | < .001 |

| Uric Acid, mg/dL | 6.24 ± 1.59 | 6.59 ± 1.57 | 6.96 ± 1.51 | < .001 | < .001 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 207.24 ± 35.37 | 213.06 ± 39.02 | 200.38 ± 39.19 | < .001 | 0.013 |

| TG, mg/dL | 127.89 ± 73.95 | 137.07 ± 91.22 | 146.40 ± 75.47 | 0.007 | 0.002 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 50.15 ± 13.87 | 48.21 ± 13.53 | 43.85 ± 10.22 | < .001 | < .001 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 128.89 ± 31.67 | 135.47 ± 34.91 | 126.45 ± 34.58 | 0.003 | 0.324 |

Data are mean ± SD or n (%). SIS indicates segment involvement score; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; eGFR, estimated Glomerular filtration; TG, triglyceride; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Former smokers were defined as individuals who declared that they ceased smoking at least 6 months prior to the study

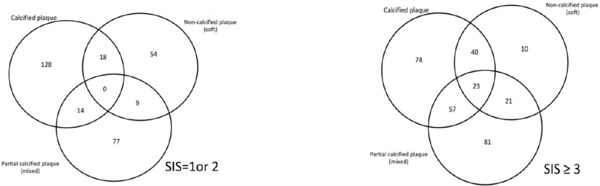

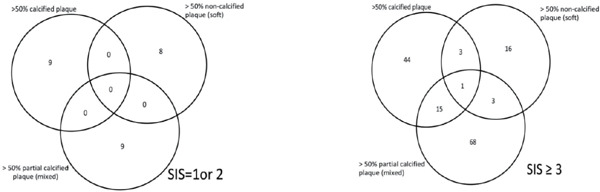

Subjects with higher SIS scores were older and had a higher BMI and blood pressure, as well as a higher prevalence of hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, smoking, and statin use (p for the trend < 0.05). Additionally, subjects with a higher SIS had higher serum levels of uric acid, triglycerides (TG), HbA1c, and glucose, and lower HDL-C levels (p for trend < 0.05). Interestingly, 32.7% of patients in the multiple atherosclerotic plaque group used statins, and the LDL-C level did not significantly correlate with a higher SIS score. Table 2 shows the patterns and severity of atherosclerotic plaques in the coronary artery. Coronary atherosclerotic plaques (lesions) were observed in approximately half the subjects, including 354 (33.2%) with calcified plaques, 175 (16.4%) with non-calcified (soft) plaques and 282 (26.5%) with partial calcified (mixed) plaques. Subjects with a higher SIS score had a higher incidence of plaques, including calcified, non-calcified (soft) and partial calcified (mixed) plaques. Among the significant (> 50%) stenotic plaques observed, 28% subjects with multiple atherosclerotic lesions (SIS ≥ 3) had > 50% stenotic partial calcified (mixed) plaques and 7.5% non-calcified (soft) and 20.6% calcified plaques. Subjects may have more than one type plaques in their coronary arteries and Supplementary Fig. 1 and 2 showed the distribution of patients having various plaque in our study population.

Table 2. Atherosclerotic plaque patterns and severity in the coronary artery in different groups of SIS.

| SIS = 0 N = 458 |

SIS = 1or 2 N = 300 |

SIS ≥ 3 N = 306 |

P value | P for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total calcium score | 1.74 ± 19.48 | 45.44 ± 106.36 | 408.43 ± 519.91 | < .001 | < .001 |

| ABOS | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.09 ± 0.29 | 1.12 ± 1.59 | < .001 | < .001 |

| SIS | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 1.49 ± 0.50 | 5.13 ± 2.18 | < .001 | < .001 |

| SSS | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 1.63 ± 0.82 | 7.29 ± 4.56 | < .001 | < .001 |

| *Calcified plaque, n (%) | 0 (0) | 160 (53.3) | 194 (63.4) | < .001 | < .001 |

| *Non-calcified plaque, n (%) | 0 (0) | 81 (27) | 94 (30.7) | < .001 | < .001 |

| *Mixed plaque, n (%) | 0 (0) | 100 (33.3) | 182 (59.5) | < .001 | < .001 |

| * > 50% calcified plaque, n (%) | 0 (0) | 9 (3) | 63 (20.6) | < .001 | < .001 |

| * > 50% non-calcified plaque, n (%) | 0 (0) | 8 (2.7) | 23 (7.5) | < .001 | < .001 |

| * > 50% mixed plaque, n (%) | 0 (0) | 9 (3) | 87 (28.4) | < .001 | < .001 |

| **CAD | |||||

| 1 vessel, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) | 33 (10.8) | < .001 | < .001 |

| 2 vessels, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (2.6) | ||

| 3 vessels, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Planed revascularization, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 37 (12) | < .001 | < .001 |

Data are mean ± SD or n (%). ABOS indicates atheroma burden obstructive score; SIS, segment involvement score; SSS, segment stenosis score SIS.

Patients who have such kinds of lesion in their coronary artery

CAD: > 70% stenosis

Supplementary Fig. 1.

Distribution of subjects with SIS = 1 & 2 (A) and SIS= 3 (B) having calcified, non-calcified (soft) and partial calcified (mixed) lesions in coronary arteries

Supplementary Fig. 2.

Distribution of subjects with SIS = 1 & 2 (A) and SIS = 3 (B) having > 50% stenotic calcified, noncalcified (soft) and partial calcified (mixed) lesions in coronary arteries

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 show the baseline characteristics in subgroups stratified by gender. Males had more risk factors and unfavorable biochemical profiles than females. In addition, males had more severe coronary atherosclerosis than females. Table 3 shows the independent predictors of coronary atherosclerosis (SIS) after adjusting for comorbidities, and only age (β = 0.085, p < 0.001), the male gender (β = 1.384, p < 0.001), BMI (β = 0.055, p = 0.019) and HbA1C levels (β = 0.894, p < 0.001) were independent predictors of greater coronary atherosclerosis involvement (SIS) in non-diabetic subjects.

Supplementary Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study subjects.

| All N = 1,064 |

Male N = 752 |

Female N = 312 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 58.18 ± 9.74 | 57.59 ± 9.87 | 59.62 ± 9.29 | 0.002 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 236 (22.2) | 160 (21.3) | 76 (24.4) | 0.313 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 331 (31.1) | 266 (35.4) | 65 (20.8) | < .001 |

| Former smoker, n (%) | 106 (10) | 101 (13.5) | 5 (1.6) | < 0.05 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 234 (22.2) | 223 (29.9) | 11 (3.6) | < 0.05 |

| Statin use, n (%) | 265 (24.9) | 186 (24.8) | 79 (25.3) | 0.911 |

| BMI, Kg/m2 | 24.86 ± 3.23 | 25.41 ± 3.00 | 23.53 ± 3.37 | < .001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 123.61 ± 16.81 | 124.90 ± 16.11 | 120.49 ± 18.03 | < .001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 78.21 ± 9.99 | 79.81 ± 9.63 | 74.34 ± 9.79 | < .001 |

| LVEF, % | 62.31 ± 7.32 | 62.38 ± 7.29 | 62.16 ± 7.40 | 0.695 |

| Framingham 10-year risk, % | 17.38 ± 13.31 | 21.41 ± 13.50 | 7.59 ± 5.41 | < .001 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.67 ± 0.31 | 5.67 ± 0.32 | 5.65 ± 0.27 | 0.139 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 91.17 ± 9.07 | 91.45 ± 9.27 | 90.50 ± 8.56 | 0.106 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 82.12 ± 14.22 | 82.21 ± 15.21 | 81.89 ± 11.50 | 0.713 |

| Uric Acid, mg/dL | 6.55 ± 1.59 | 7.01 ± 1.50 | 5.44 ± 1.21 | < .001 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 91.17 ± 9.07 | 91.45 ± 9.27 | 90.50 ± 8.56 | 0.106 |

| TG, mg/dL | 127.89 ± 73.95 | 137.07 ± 91.22 | 146.40 ± 75.47 | 0.007 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 47.79 ± 13.08 | 43.99 ± 10.50 | 56.99 ± 14.10 | < .001 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 130.05 ± 33.61 | 128.71 ± 34.02 | 133.29 ± 32.44 | 0.043 |

Data are mean ± SD or n (%).SIS indicates segment involvement score; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; eGFR, estimated Glomerular filtration; TG, triglyceride; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Supplementary Table 2. Atherosclerotic plaque patterns and severity in the coronary artery in different genders.

| All N = 1,064 |

Male N = 752 |

Female N = 312 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total calcium score | 131.38 ± 335.37 | 170.86 ± 383.56 | 36.92 ± 130.78 | < .001 |

| ABOS | 0.35 ± 0.99 | 0.45 ± 1.14 | 0.09 ± 0.38 | < .001 |

| SIS | 1.90 ± 2.46 | 2.34 ± 2.67 | 0.82 ± 1.37 | < .001 |

| SSS | 2.56 ± 3.96 | 3.21 ± 4.40 | 0.97 ± 1.83 | < .001 |

| Calcified plaque, n (%) | 354 (33.3) | 288 (38.3) | 66 (21.2) | < .001 |

| Non-calcified plaque, n (%) | 175 (16.4) | 137 (18.2) | 38 (12.2) | 0.020 |

| Mixed plaque, n (%) | 282 (26.5) | 243 (32.3) | 39 (12.5) | < .001 |

| > 50% calcified plaque, n (%) | 72 (6.8) | 58 (7.7) | 14 (4.5) | 0.076 |

| > 50% non-calcified plaque, n (%) | 31 (2.9) | 27 (3.6) | 4 (1.3) | 0.066 |

| > 50% mixed plaque, n (%) | 96 (9) | 91 (12.1) | 5 (1.6) | < .001 |

| *CAD | ||||

| 1 vessel, n (%) | 35 (3.3) | 33 (4.4) | 2 (0.6) | < .003 |

| 2 vessels, n (%) | 8 (0.8) | 8 (1.1) | 0 (0) | |

| 3 vessels, n (%) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

Data are mean ± SD or n (%). ABOS indicates atheroma burden obstructive score; SIS, segment involvement score; SSS, segment stenosis score SIS.

CAD: > 70% stenosis

Table 3. Independent predictors for coronary atherosclerosis (SIS).

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% Confidence Interval | P value | β | 95% Confidence Interval | P value | |

| Age, years | 0.085 | (0.070–0.099) | < .001 | 0.085 | (0.069–0.100) | < .001 |

| Male, n (%) | 1.519 | (1.207–1.831) | < .001 | 1.384 | (1.022–1.745) | < .001 |

| BMI, Kg/m2 | 0.142 | (0.097–0.187) | < .001 | 0.055 | (0.009–0.101) | 0.019 |

| SBP, mmHg | 0.028 | (0.019–0.036) | < .001 | |||

| TG, mg/dL | 0.003 | (0.001–0.005) | 0.002 | |||

| HDL-C, mg/dL | −0.037 | (−0.048–−0.025) | < .001 | |||

| LDL-C, mg/dL | −0.006 | (−0.010–−0.002) | 0.009 | |||

| HbA1c, % | 1.861 | (1.397–2.325) | < .001 | 0.894 | (0.443–1.345) | < .001 |

| Uric Acid, mg/dL | 0.209 | (0.116–0.301) | < .001 | |||

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | −0.019 | (−0.029–−0.008) | < .001 | |||

| * Former smoker | 0.493 | (0.004–0.981) | 0.048 | |||

| Current smoker | 0.338 | (−0.015–0.692) | 0.061 | |||

Data are mean ± SD or n (%). BMI indicates body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TG, triglyceride; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; eGFR, estimated Glomerular filtration;

Former smokers were defined as individuals who declared that they ceased smoking at least 6 months prior to the study

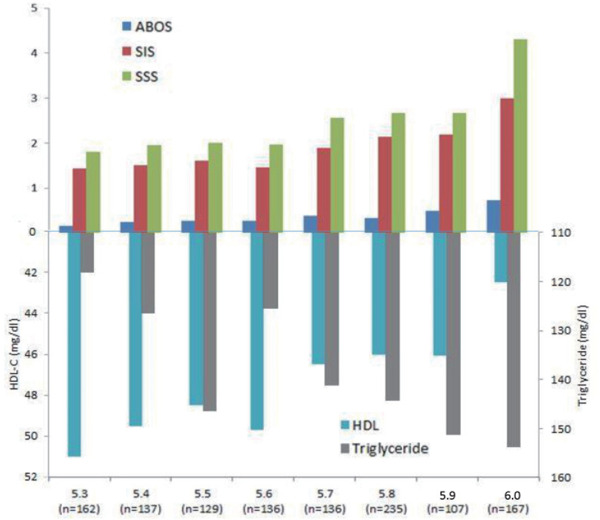

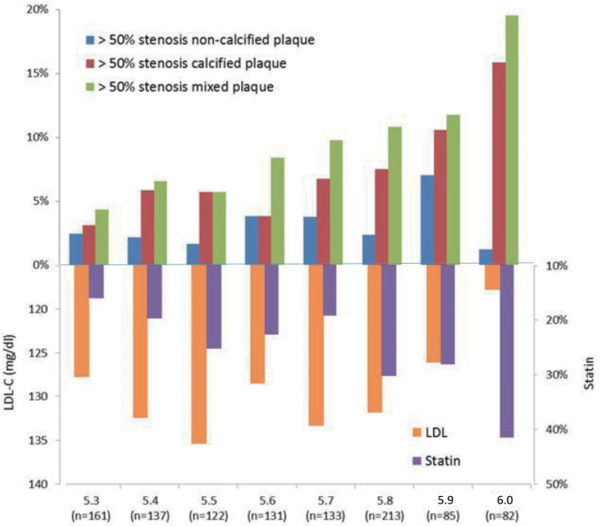

Table 4 shows the predictors of the presence of significant > 50% stenotic calcified, non-calcified (soft) and partial calcified (mixed) plaques. For calcified plaques, only age (OR: 1.082, 95% CI: 10.47–1.118) and a former smoking status (OR: 2.061, 95% CI: 1.013–4.193) were independently associated with the presence of significant stenotic calcified plaques in non-diabetic subjects. For the presence of significant stenotic partial calcified (mixed) type plaques, only age (OR: 1.085, 95% CI: 1.052–1.119), the male gender (OR: 7.082, 95% CI: 2.638–19.018), HbA1C levels (OR: 2.074, 95% CI: 1.036–4.151), and current smoking status (OR: 1.848, 95% CI: 1.089–3.138) were independently associated with the risk of the presence of significant stenotic partial calcified (mixed) plaques. For non-calcified (soft) plaques, no factors achieved statistical significance. Fig. 3 shows the correlations between HbA1c levels and various coronary atherosclerotic characteristics and the LDL values. Fig. 4 shows the correlations between HbA1c levels and CAD severity and the TG and HDL-C levels.

Table 4. Predictors for the presence of > 50% stenotic plaque of calcified, non-calcified and mixed characteristics.

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odd Ratio | 5% Confidence interval | P value | Odd Ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P value | |

| Calcified plaque | ||||||

| Age, years | 1.077 | 1.050–1.106 | < .001 | 1.080 | 1.045–1.116 | < .001 |

| Male, n (%) | 1.779 | 0.977–3.239 | 0.060 | 1.185 | 0.571–2.461 | .648 |

| BMI, Kg/m2 | 1.027 | 0.955–1.105 | 0.470 | 0.958 | 0.876–1.047 | .344 |

| SBP, mmHg | 1.022 | 1.008–1.036 | 0.001 | 1.009 | 0.994–1.024 | .253 |

| TG, mg/dL | 1.001 | 0.998–1.004 | 0.513 | 1.000 | 0.996–1.003 | .827 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 0.974 | 0.953–0.995 | 0.014 | 0.976 | 0.950–1.003 | .084 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 0.995 | 0.988–1.002 | 0.196 | 0.999 | 0.992–1.007 | .875 |

| HbA1c, % | 3.892 | 1.949–7.770 | < .001 | 2.155 | 0.988–4.700 | .054 |

| Uric Acid, mg/dL | 1.144 | 0.993–1.319 | 0.062 | 1.062 | 0.890–1.268 | .502 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 0.981 | 0.965–0.997 | 0.024 | 1.003 | 0.984–1.021 | .775 |

| Former smoker | 2.438 | 1.282–4.638 | 0.007 | 2.061 | 1.013–4.193 | .046 |

| Current smoker | 1.176 | 0.648–2.134 | 0.594 | 1.331 | 0.682–2.596 | .402 |

| Non-calcified plaque (soft) | ||||||

| Age, years | 1.028 | 0.991–1.066 | 0.142 | 1.026 | 0.981–1.072 | .259 |

| Male, n (%) | 2.868 | 0.995–8.264 | 0.051 | 3.007 | 0.891–10.148 | .076 |

| BMI, Kg/m2 | 0.999 | 0.894–1.116 | 0.988 | 0.966 | 0.843–1.106 | .615 |

| SBP, mmHg | 0.998 | 0.977–1.020 | 0.890 | 0.989 | 0.966–1.013 | .377 |

| TG, mg/dL | 1.001 | 0.998–1.005 | 0.513 | 1.001 | 0.996–1.006 | .717 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 0.990 | 0.961–1.019 | 0.490 | 1.006 | 0.971–1.043 | .732 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 0.999 | 0.989–1.010 | 0.912 | 1.000 | 0.989–1.011 | .965 |

| HbA1c, % | 1.288 | 0.421–3.945 | 0.657 | 1.006 | 0.297–3.406 | .992 |

| Uric Acid, mg/dL | 1.224 | 1.002–1.496 | 0.048 | 1.109 | 0.875–1.406 | .391 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 0.972 | 0.949–0.996 | 0.022 | 0.980 | 0.954–1.007 | .145 |

| Former smoker | 1.363 | 0.457–4.067 | 0.579 | 1.091 | 0.355–3.353 | .879 |

| Current smoker | 1.072 | 0.447–2.567 | 0.877 | 0.885 | 0.349–2.241 | .796 |

| Partial calcified plaque (mixed) | ||||||

| Age, years | 1.071 | 1.047–1.096 | < .001 | 1.085 | 1.052–1.119 | < .001 |

| Male, n (%) | 8.453 | 3.401–21.008 | < .001 | 7.082 | 2.638–19.018 | < .001 |

| BMI, Kg/m2 | 1.111 | 1.045–1.182 | 0.001 | 1.065 | 0.986–1.151 | .108 |

| SBP, mmHg | 1.025 | 1.012–1.037 | < .001 | 1.010 | 0.996–1.024 | .180 |

| TG, mg/dL | 1.003 | 1.001–1.005 | 0.014 | 1.001 | 0.999–1.004 | .283 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 0.957 | 0.938–0.977 | < .001 | 0.986 | 0.961–1.012 | .279 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 0.994 | 0.987–1.000 | 0.048 | 1.000 | 0.993–1.007 | .945 |

| HbA1c, % | 4.504 | 2.439–8.316 | < .001 | 2.074 | 1.036–4.151 | .039 |

| Uric Acid, mg/dL | 1.148 | 1.013–1.301 | 0.031 | 0.931 | 0.796–1.089 | .373 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 0.981 | 0.967–0.996 | 0.011 | 1.001 | 0.985–1.017 | .920 |

| Former smoker | 1.208 | 0.576–2.532 | 0.617 | 0.675 | 0.306–1.489 | .330 |

| Current smoker | 2.138 | 1.342–3.404 | 0.001 | 1.848 | 1.089–3.138 | .023 |

Data are mean ± SD or n (%). BMI indicates body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TG, triglyceride; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; eGFR, estimated Glomerular filtration;

Fig. 3.

The presence of significant (> 50% stenosis) high-risk plaques (mixed plaques with spotty calcification) in the coronary artery (A & B); (C) the associations of serum LDL-C levels and statin use and various significant (> 50% stenosis) plaques in in non-diabetic subjects with different HbA1c levels

Fig. 4.

The association between lipid profiles of serum triglyceride (TG) and HDL-C levels and the severity of coronary artery atherosclerosis in non-diabetic subjects with different HbA1c levels

Discussion

As shown in the present study, a higher HbA1c level was associated with more advanced coronary atherosclerosis, even when LDL-C levels were tightly controlled. Additionally, although higher HDL-C levels and lower TG levels were associated with a higher severity of coronary atherosclerosis, higher HbA1c levels were still independently associated with the risk of the presence of high-risk plaques, suggesting that the maintenance of lower HbA1c levels is very important to prevent atherosclerosis in low-risk subjects.

DM is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease and is often accompanied by macrovascular complications1). Patients with diabetes have a higher prevalence of atherosclerosis, CAD, and silent lesions within the coronary artery, even in the absence of clinical ischemic symptoms9, 10). However, the atherosclerotic process appears to begin very early, even in patients without symptoms and only minimal risk factors. Although a diagnosis of diabetes was not achieved, Scicali et al. reported a higher coronary calcium level and carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) in subjects with an HbA1c level of 5.7–6.4% than in subjects with an HbA1c level < 5.7%11), suggesting that atherosclerosis was already present in people with pre-diabetes. Recently, subclinical atherosclerosis was observed in 47% of CV risk-free subjects (blood sugar level < 126 mg/dL and LDL-C level < 160 mg/dL)4). Both observations showed that atherosclerosis exists early, even if blood sugar and LDL-C levels are still within acceptable ranges in low-risk subjects. Our current study further extended the previous observation showing that changes in plaque characteristics are associated with higher HbA1c levels in non-diabetic subjects. As HbA1c levels increase, a higher percentage of coronary plaques, particularly partial calcified (mixed) plaques, was observed, and approximately 20% of non-diabetic subjects whose HbA1c level was approximately 6.0% had partial calcified (mixed) plaques with > 50% stenosis in their coronary arteries. The results from the current study are consistent with previous studies showing a correlation between a higher HbA1c level and a higher coronary atherosclerotic burden in non-diabetic patients11), but we extended these findings to show that this parameter is particularly associated with the presence of high-risk mixed plaques. Several features of coronary CTA have been identified as characteristics of vulnerable plaques. Plaques with spotty calcification were the most frequently reported high-risk plaque feature (risk ratio [RR]: 37.2), followed by > 50% stenosis (RR: 34.4), positive remodeling (RR: 11.3), low Hounsfield units (HU) plaques (RR: 8.2), and a napkin ring sign (RR: 8.2)12). Our current study defined > 50% stenosis and partial calcified (mixed) type plaques as the high-risk plaques, consistent with the findings described above. Additionally, Hou et al. estimated that the 3-year probability of major cardiovascular events was 6% for a calcified plaque, 23% for a non-calcified plaque, and 38% for a mixed plaque in a cohort of subjects suspected of having CAD13). These results supported the hypothesis that the highest risks are associated mixed plaques and suggested that a risky plaque composition (less calcified plaques and more mixed plaques) should be avoided to prevent adverse cardiovascular events14).

In the present study, age, the male gender, HbA1c level and a current smoking status were independently associated with the presence of high-risk partial calcified (mixed) plaques in non-diabetic subjects. LDL-C levels are not related to the extent of coronary plaques, which is believed to be caused by statin therapy and a higher statin prescription rate in patients with a higher HbA1c level. Although Fernández-Friera et al. reported that LDL-C is an independent factor associated with the atherosclerosis process4), our study revealed that atherosclerosis progressed even when LDL-C levels were controlled by statin therapy. Although statin therapy has been widely used to control risks, studies aiming to identify if other residual risk factors are needed. As shown in the present study, higher serum levels of TGs and lower serum levels of HDL-C were associated with a higher percentage of coronary plaques with higher HbA1c levels. Although the trends for associations between changes in TG and HDL-C levels with more coronary plaque involvement were observed, TG and HDL-C levels were not independently correlated with coronary plaque formation after simultaneous adjustment for HbA1c levels, indicating that HbA1c plays a crucial role in coronary atherosclerosis, particularly the development of significant stenotic calcified and partial calcified (mixed) plaques. Higher HbA1C levels correlated with a higher clinical risk, even in nondiabetic patients. An increased risk of ischemic stroke has been reported when HbA1c levels exceed 5.6%15, 16). A meta-analysis including 36 observational cohort and nested case-control cohort studies showed a 49% increase in the risk of first-ever ischemic stroke for every 1% increase in the HbA1c level in non-diabetic cohorts17), suggesting that maintaining lower HbA1c levels protects patients from adverse CV events. Furthermore, our current study showed that former smokers exhibit a higher risk of significant calcified plaques and current smokers have a higher risk of partial calcified (mixed) plaques. Although the mechanism remains unclear, a study investigating the effects of tobacco use and cessation on coronary atherosclerosis reported that a current smoking status is independently associated with coronary plaques and prior smoking cessation correlated with improvements in coronary plaques18). Our study is consistent with the finding that current smokers without diabetes exhibit a higher risk of partial calcified (mixed) type plaques. A study analyzing a larger sample or molecular study may be needed to elucidate the effect of the smoking status on atherosclerosis.

Several limitations of this study should be mentioned. First, patients were recruited from only one center and the sample size was moderate. In addition, although our study only included people of Asian ethnicity without long-term outcome information, higher HbA1c levels have been reported to be associated with a higher risk of poor outcomes in diabetic and nondiabetic populations19). Furthermore, all study subjects were enrolled at our healthcare center, not cardiovascular clinic, were not diagnosed with diabetes, did not have a prior history of CAD, and the coronary atherosclerosis was not severe. Therefore, we used SIS (1–16) to represent the degree of coronary plaque involvement, and not SSS (1–48), because few subjects had a high SSS. Actually, strong correlations were observed between the SSS, SIS, ABOS and calcium scores (Supplementary Table 3). Finally, we defined plaque morphology as calcified, non-calcified (soft) and partial calcified (mixed) plaque in our study, not completely assessed based on SCCT recommendation. Although partial calcified (mixed) plaque has many features of vulnerable plaque, it is not completely match the CT-verified high-risk plaque such as low attenuation plaque, spotty calcification and napkinring sign.

Supplementary Table 3. Correlation of parameters of CCTA.

| CAC score | ABOS | SIS | SSS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAC score correlation | 1 | 0.627 | 0.707 | 0.748 |

| Significance | < 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

| ABOS correlation | 1 | 0.643 | 0.776 | |

| Significance | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||

| SIS correlation | 1 | 0.944 | ||

| Significance | 0.001 | |||

| SSS correlation | 1 | |||

| Significance | ||||

CAC indicates coronary artery calcification; ABOS, atheroma burden obstructive score; SIS, segment involvement score SSS, segment stenosis score

Conclusions

An increase in HbA1c levels is independently associated with the presence and severity of coronary artery atherosclerosis in non-diabetic patients. Additionally, although higher HDL-C levels and lower TG levels were observed in patients with an higher severity of coronary atherosclerosis and increased serum HbA1C levels, only HbA1C levels were independently associated with a higher risk of severe coronary artery atherosclerosis and the presence of significant mixed type plaques, even if LDL-C levels were controlled by statin therapy. Thus, HbA1c is a useful indicator to identify high-risk subjects, even in non-diabetic populations, and maintaining a lower HbA1c level is a beneficial strategy to reduce the cardiovascular risk in non-diabetic patients.

Disclosure Summary

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

No grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) VIII. Study design, progress and performance. Diabetologia, 1991; 34: 877-890 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, Braun LT, de Ferranti S, Faiella-Tommasino J, Forman DE, Goldberg R, Heidenreich PA, Hlatky MA, Jones DW, Lloyd-Jones D, Lopez-Pajares N, Ndumele CE, Orringer CE, Peralta CA, Saseen JJ, Smith SC, Jr, Sperling L, Virani SS, Yeboah J: 2018AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2019; 73: 3237-324131221270 [Google Scholar]

- 3). Hadamitzky M, Hein F, Meyer T, Bischoff B, Martinoff S, Schomig A, Hausleiter J: Prognostic value of coronary computed tomographic angiography in diabetic patients without known coronary artery disease. Diabetes Care, 2010; 33: 1358-1363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Fernandez-Friera L, Fuster V, Lopez-Melgar B, Oliva B, Garcia-Ruiz JM, Mendiguren J, Bueno H, Pocock S, Ibanez B, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Sanz J: Normal LDLCholesterol Levels Are Associated With Subclinical Atherosclerosis in the Absence of Risk Factors. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2017; 70: 2979-2991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Abbara S, Blanke P, Maroules CD, Cheezum M, Choi AD, Han BK, Marwan M, Naoum C, Norgaard BL, Rubinshtein R, Schoenhagen P, Villines T, Leipsic J: SCCT guidelines for the performance and acquisition of coronary computed tomographic angiography: A report of the society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee: Endorsed by the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging (NASCI). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr, 2016; 10: 435-449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Min JK, Shaw LJ, Devereux RB, Okin PM, Weinsaft JW, Russo DJ, Lippolis NJ, Berman DS, Callister TQ: Prognostic value of multidetector coronary computed tomographic angiography for prediction of all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2007; 50: 1161-1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Lee KY, Hwang BH, Kim TH, Kim CJ, Kim JJ, Choo EH, Choi IJ, Choi Y, Park HW, Koh YS, Kim PJ, Lee JM, Kim MJ, Jeon DS, Cho JH, Jung JI, Seung KB, Chang K: Computed Tomography Angiography Images of Coronary Artery Stenosis Provide a Better Prediction of Risk Than Traditional Risk Factors in Asymptomatic Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes: A Long-term Study of Clinical Outcomes. Diabetes Care, 2017; 40: 1241-1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Huang SS, Chan WL, Leu HB, Huang PH, Lin SJ, Chen JW: Serum bilirubin levels predict future development of metabolic syndrome in healthy middle-aged nonsmoking men. Am J Med, 2015; 128: 1138.e1135-1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Andreini D, Pontone G, Bartorelli AL, Agostoni P, Mushtaq S, Antonioli L, Cortinovis S, Canestrari M, Annoni A, Ballerini G, Fiorentini C, Pepi M: Comparison of the diagnostic performance of 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography in diabetic and non-diabetic patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2010; 9: 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Zellweger MJ, Hachamovitch R, Kang X, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, Germano G, Pfisterer ME, Berman DS: Prognostic relevance of symptoms versus objective evidence of coronary artery disease in diabetic patients. Eur Heart J, 2004; 25: 543-550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Scicali R, Giral P, Gallo A, Di Pino A, Rabuazzo AM, Purrello F, Cluzel P, Redheuil A, Bruckert E, Rosenbaum D: HbA1c increase is associated with higher coronary and peripheral atherosclerotic burden in non diabetic patients. Atherosclerosis, 2016; 255: 102-108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Puchner SB, Liu T, Mayrhofer T, Truong QA, Lee H, Fleg JL, Nagurney JT, Udelson JE, Hoffmann U, Ferencik M: High-risk plaque detected on coronary CT angiogra phy predicts acute coronary syndromes independent of significant stenosis in acute chest pain: results from the ROMICAT-II trial. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2014; 64: 684-692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Hou ZH, Lu B, Gao Y, Jiang SL, Wang Y, Li W, Budoff MJ: Prognostic value of coronary CT angiography and calcium score for major adverse cardiac events in outpatients. JACC Cardiovascular imaging, 2012; 5: 990-999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Aengevaeren VL, Mosterd A, Braber TL, Prakken NHJ, Doevendans PA, Grobbee DE, Thompson PD, Eijsvogels TMH, Velthuis BK: Relationship Between Lifelong Exercise Volume and Coronary Atherosclerosis in Athletes. Circulation, 2017; 136: 138-148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Sigal RJ: Hemoglobin A1c levels were associated with increased cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in persons with and without diabetes. ACP J Club, 2005; 142: 52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Nomani AZ, Nabi S, Ahmed S, Iqbal M, Rajput HM, Rao S: High HbA1c is associated with higher risk of ischaemic stroke in Pakistani population without diabetes. Stroke Vask Neurol, 2016; 1: 133-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Mitsios JP, Ekinci EI, Mitsios GP, Churilov L, Thijs V: Relationship Between Glycated Hemoglobin and Stroke Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc, 2018; 7 pii:e007858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Cheezum MK, Kim A, Bittencourt MS, Kassop D, Nissen A, Thomas DM, Nguyen B, Glynn RJ, Shah NR, Villines TC: Association of tobacco use and cessation with coronary atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis, 2017; 257: 201-207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Cavero-Redondo I, Peleteiro B, Alvarez-Bueno C, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Martinez-Vizcaino V: Glycated haemoglobin A1c as a risk factor of cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality in diabetic and non-diabetic populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open, 2017; 7: e015949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA, 2001; 285: 2486-2497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]