Abstract

UDP-glucuronic acid is converted to UDP-galacturonic acid en route to a variety of sugar-containing metabolites. This reaction is performed by a NAD+-dependent epimerase belonging to the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family. We present several high-resolution crystal structures of the UDP-glucuronic acid epimerase from Bacillus cereus. The geometry of the substrate-NAD+ interactions is finely arranged to promote hydride transfer. The exquisite complementarity between glucuronic acid and its binding site is highlighted by the observation that the unligated cavity is occupied by a cluster of ordered waters whose positions overlap the polar groups of the sugar substrate. Co-crystallization experiments led to a structure where substrate- and product-bound enzymes coexist within the same crystal. This equilibrium structure reveals the basis for a “swing and flip” rotation of the pro-chiral 4-keto-hexose-uronic acid intermediate that results from glucuronic acid oxidation, placing the C4′ atom in position for receiving a hydride ion on the opposite side of the sugar ring. The product-bound active site is almost identical to that of the substrate-bound structure and satisfies all hydrogen-bonding requirements of the ligand. The structure of the apoenzyme together with the kinetic isotope effect and mutagenesis experiments further outlines a few flexible loops that exist in discrete conformations, imparting structural malleability required for ligand rotation while avoiding leakage of the catalytic intermediate and/or side reactions. These data highlight the double nature of the enzymatic mechanism: the active site features a high degree of precision in substrate recognition combined with the flexibility required for intermediate rotation.

Keywords: SDR, short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase, epimerase, decarboxylase, catalytic intermediates, UDP-glucuronic acid, UDP-galacturonic acid, NADH, kinetic isotope effect, crystal structure, enzyme mechanism, dehydrogenase, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), substrate specificity

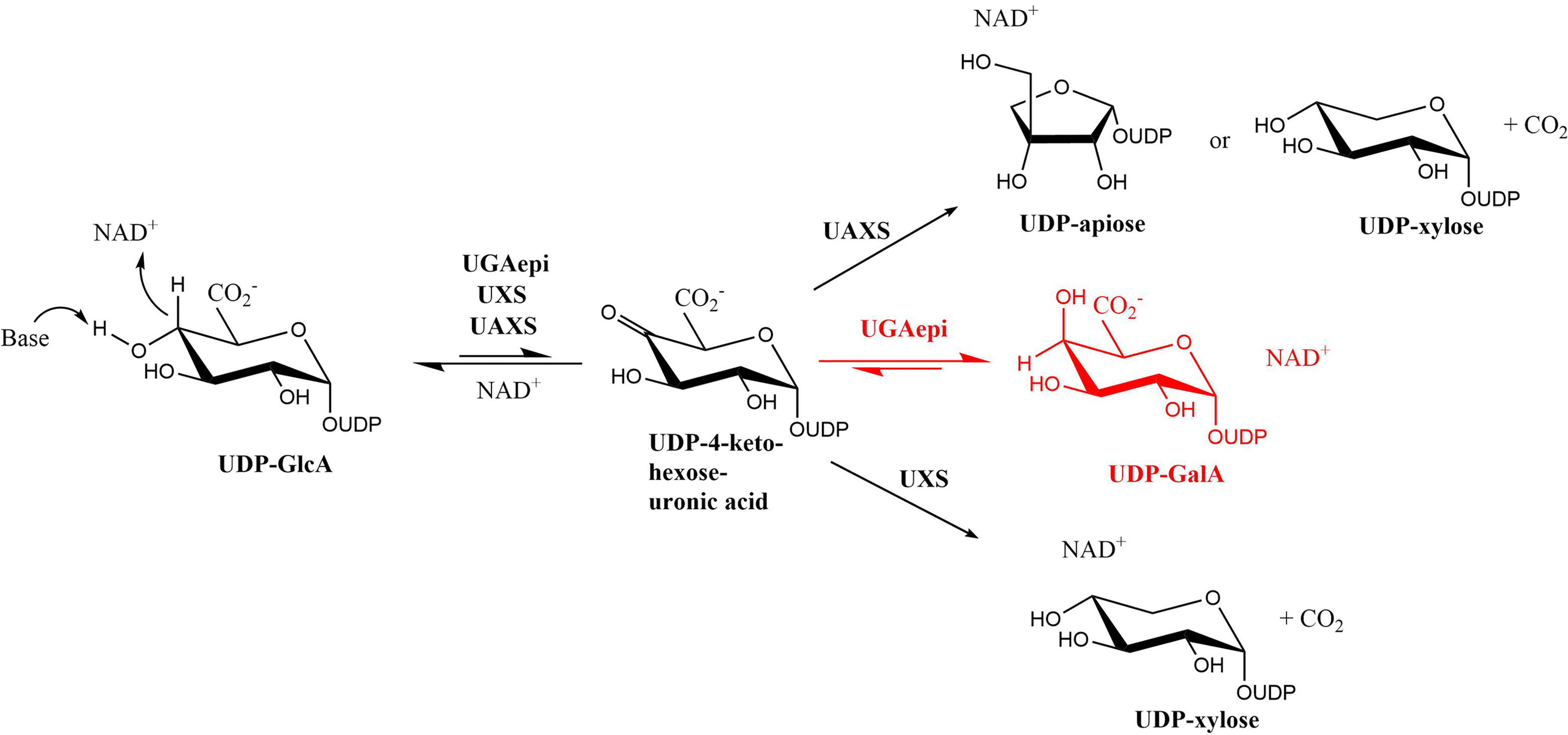

Nucleotide sugars are high-energy donor molecules that fulfill many roles, including contributing to cellular and tissue structural integrity (1–3), acting as molecular recognition markers for xenobiotic detoxification (4–6), and providing scaffolds for drug development (7). Among these metabolites, UDP-glucuronic acid (UDP-GlcA) represents a very versatile compound that undergoes a variety of enzymatic modifications. UDP-glucuronic acid 4-epimerase (EC 5.1.3.6), UDP-xylose synthase (EC 4.1.1.35), and UDP-apiose/xylose synthase (EC 4.1.1.-) modify UDP-GlcA through NAD+-dependent redox chemistry, producing enzyme-specific sugar products (8–10). These structurally and functionally related enzymes belong to the family of the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductases (SDRs) (11). SDRs are characterized by a strictly conserved catalytic triad, Ser/Thr-Tyr-Lys. The tyrosine residue functions as the base that abstracts a proton from the substrate 4′-OH group and promotes C4′ oxidation by NAD+ (12–18). The generated 4-keto-hexose-uronic acid intermediate is unstable and converted into different products, depending on the enzyme (Scheme 1). Because of their catalytic versatility, sugar-modifying SDR enzymes are increasingly recognized as valuable targets for many industrial biocatalytic applications.

Scheme 1.

Reactions carried out by UDP-glucuronic acid epimerase (UGAepi), UDP-xylose synthase (UXS) and UDP-apiose/xylose synthase (UAXS) using UDP-GlcA as substrate. The same 4-keto-hexose-uronic acid intermediate yields different products that are specific for every enzyme.

As can be seen from Scheme 1, the UDP-glucuronic acid 4-epimerase stands out for its ability to prevent decarboxylation at the C5′ position of the 4-keto-hexose-uronic acid intermediate. This enzyme thereby efficiently interconverts UDP-GlcA into UDP-galacturonic acid (UDP-GalA) by inverting the configuration of the 4′-carbon. The strategies used by epimerases to invert the stereochemistry of UDP-sugar carbons have been subject of in-depth investigations (12). Among these, the structural features underlying the selective C4′ epimerization by UDP-galactose 4-epimerase were extensively studied in the past few years (13, 18, 19). This enzyme is part of the Leloir pathway and interconverts UDP-galactose into UDP-glucose (20). It belongs to the SDR family, featuring the same Ser/Thr-Tyr-Lys catalytic triad as UDP-glucuronic acid 4-epimerase. The substrate is first oxidized at the C4′, and the resulting 4-keto-hexose intermediate is thought to undergo a rotational movement within the active site. The intermediate is then reduced by NADH, leading to the inversion of the C4′ configuration (18, 21). The same catalytic strategy has been hypothesized also for the epimerases acting on UDP-GlcA (22). As demonstrated by recent work, these enzymes fine-tune the rates of the individual redox steps to prevent the accumulation of the 4-keto-hexose-uronic acid, minimizing the undesired decarboxylation and/or release of this reactive intermediate (23).

Whereas the catalytic mechanisms of UDP-xylose synthase and UDP-apiose/xylose synthase have been thoroughly elucidated (13, 16, 24), the epimerization reaction by UDP-glucuronic acid 4-epimerase remains partly unexplored. In this work, we carried out a comprehensive structural analysis of UDP-glucuronic acid 4-epimerase from Bacillus cereus (BcUGAepi) by solving six high-resolution crystal structures that elucidate different steps along the reaction. The main aspects of these structures were compared with other SDR epimerases and decarboxylases. We also isolated a remarkable complex showing an equilibrium mixture of both substrate and product in approximately 1:1 ratio. We further used structural, kinetic isotope effect and site-directed mutagenesis experiments to inspect the fine roles of catalytic residues. Our studies provide an overview of catalysis with critical insight into the mechanism of 4-ketose-uronic acid intermediate rotation and protection against intermediate decarboxylation. They further demonstrate that the UDP moiety is not only an accessory part of the molecule, but it is fundamental for substrate recognition and active-site configuration.

Results and discussion

Overall structure

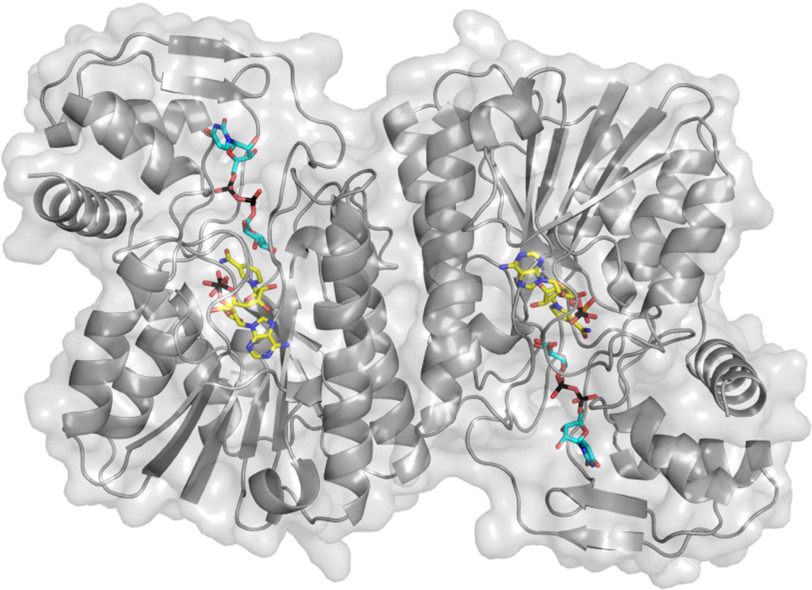

The crystal structure of BcUGAepi co-purified with NAD+ was initially solved at 2.2 Å resolution by molecular replacement (Table 1). The enzyme is composed of nine β-strands and eight α-helices assembled in two domains (13, 27, 28) (Fig. 1). The N-terminal domain is characterized by a Rossmann fold motif comprising a core of seven β-strands surrounded by six α-helices. The NAD+ cofactor is fully embedded within this domain, whereas the smaller C-terminal domain provides the binding site for the UDP-GlcA substrate. The crevice between the two domains encloses the active site (29–31). As for other SDR family enzymes, two protein chains are arranged to form a tight homodimer (11, 32, 33) where each subunit (37 kDa) interacts with two adjacent α-helices, generating an extensively intermolecular hydrophobic core of four α-helices (14, 16) (Fig. 1). Structural comparisons using the Dali server (34) indicate that the overall structure of BcUGAepi is similar to the structures of UDP-galactose 4-epimerase from Escherichia coli (PDB entry 1UDA) (29–31) and MoeE5 (a UDP-glucuronic acid epimerase from Streptomyces viridosporus; PDB entry 6KV9) (22) with Z scores of 37.2 and 42.8 and sequence identities of 30 and 38%, respectively.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for the UGAepi crystal structures

| NAD+ | NAD+/UDP | NAD+/UDP-GlcA | NAD+/UDP-GlcA/UDP-GalA | NAD+/4F-UDP-GlcA | NAD+/UDP-GalA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | C2 | P1 | P1 | P21 | P1 | P1 |

| Unit cell axes (Å) | 214.5, 78.5, 87.9 | 42.5, 58.6, 64.9 | 42.4, 58.4, 64.7 | 53.7, 124.3, 98.4 | 42.2, 58.2, 64.4 | 56.8, 62.7, 105.8 |

| Unit cell angles (degrees) | 90.0, 91.0, 90.0 | 96.8, 98.4, 110.3 | 96.8, 98.4, 110.6 | 90.0, 90.6, 90.0 | 97.2, 98.2, 109.9 | 91.9, 99.9, 92.0 |

| No. of chains/asymmetrical unit | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Resolution (Å) | 45.6–2.20 (2.25–2.20)a | 45.3–1.70 (1.74–1.70) | 45.2–1.80 (1.84–1.80) | 49.4–1.50 (1.53–1.50) | 45.2–1.70 (1.74–1.70) | 46.1–1.85 (1.89–1.85) |

| PDB code | 6ZLA | 6ZL6 | 6ZLD | 6ZLK | 6ZLJ | 6ZLL |

| Rsymb (%) | 4.6 (20.8) | 6.5 (55.7) | 8.4 (25.9) | 8.3 (157) | 13.7 (239) | 11.6 (228) |

| CC1/2c (%) | 99.9 (92.6) | 99.7 (88.1) | 99.7 (78.0) | 99.5 (18.8) | 99.6 (68.0) | 99.7 (46.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 98 (92.6) | 93 (91) | 93.7 (92) | 97.5 (97.5) | 92.4 (90.8) | 92.6 (83.6) |

| Unique reflections | 72,646 | 58,368 | 49,095 | 190,286 | 57,074 | 113,316 |

| Redundancy | 4.2 (3.2) | 1.7 (1.7) | 1.6 (1.7) | 3.8 (3.9) | 9.1 (9.5) | 6.9 (6.4) |

| I/σ | 16.9 (4.6) | 10.2 (1.2) | 9.3 (2.5) | 7.0 (1.0) | 8.4 (1.5) | 8.7 (1.1) |

| No. of nonhydrogen atoms | ||||||

| Protein | 9714 | 4932 | 4934 | 9869 | 4930 | 9988 |

| Ligands | 176 | 138 | 160 | 470 | 160 | 320 |

| Waters | 243 | 251 | 298 | 695 | 170 | 242 |

| Average B value for protein/ligand atoms (Å2) | 34.2/25.4 | 25.59/25.8 | 22.4/18.7 | 23.6/22.8 | 29.3/26.4 | 37.14/ 38.12 |

| Rcryst (%) | 17.8 (21.5) | 17.0 (28.6) | 16.8 (24.8) | 17.2 (32.2) | 17.2 (29.7) | 18.7 (32.2) |

| Rfree (%) | 22.7 (26.5) | 20.0 (30.7) | 20.7 (27.1) | 20.3 (30.9) | 21.6 (30.7) | 22.2 (34.0) |

| Root mean square deviations from standard values | ||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.087 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.008 |

| Bond angles (degrees) | 1.58 | 1.68 | 1.57 | 1.73 | 1.60 | 1.58 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||||||

| Preferred (%) | 97.5 | 98.0 | 98.0 | 97.7 | 98.0 | 97.3 |

| Allowed (%) | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 2.2 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

aValues in parentheses are for reflections in the highest-resolution shell.

bRsym = ∑|Ii − 〈I〉|/∑Ii, where Ii is the intensity of the ith observation and is the mean intensity of the reflection.

cThe resolution cut-off was set to CC1/2 > 0.3, where CC1/2 is the Pearson correlation coefficient of two “half” data sets, each derived by averaging half of the observations for a given reflection. The data set for the equilibrium structure features some mild anisotropy. Following the resolution estimation given by the program Aimless (25) and based on the visual inspection of the electron density maps, only for this data set we included data with a somewhat lower CC1/2 value (26).

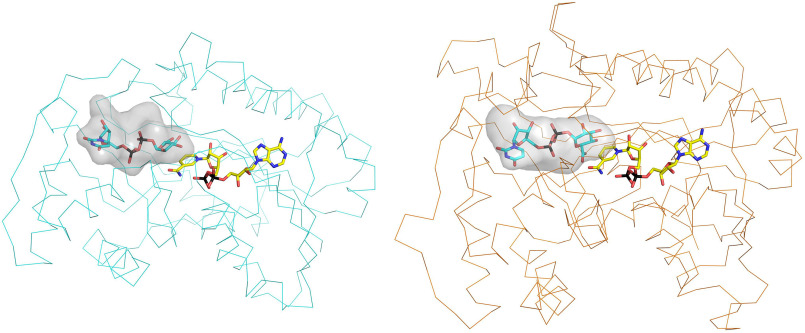

Figure 1.

The overall structure of the dimeric UDP-glucuronic acid 4-epimerase from B. cereus. The NAD+ and UDP-GlcA carbons are shown in yellow and cyan, respectively. The backbone trace is shown as a gray ribbon and semitransparent protein surface.

NAD+ remains tightly associated to the enzyme during the entire purification process (Fig. 2A) (11, 13, 35). It is bound in an elongated conformation as typically observed in other SDR enzymes (21, 28, 36). Its binding is extensively stabilized through several interactions with residues of the Rossmann fold domain. The amine group of the adenine ring hydrogen-bonds to Asn-101 and Asp-62, the adenine-ribose hydroxyl groups interact with Asp-32 and Lys-43, the β-phosphate is ionically bound to Arg-185, and the nicotinamide ribose is hydrogen-bonded to Tyr-149 and Lys-153. These last two residues belong to the Tyr-X-X-X-Lys motif of the Ser/Thr-Tyr-Lys triad, the typical hallmark of SDR enzymes (32, 37–39). This binding mode orients the si-face on the nicotinamide ring toward the substrate-binding site to cope with the sugar moiety and mediate hydride transfer.

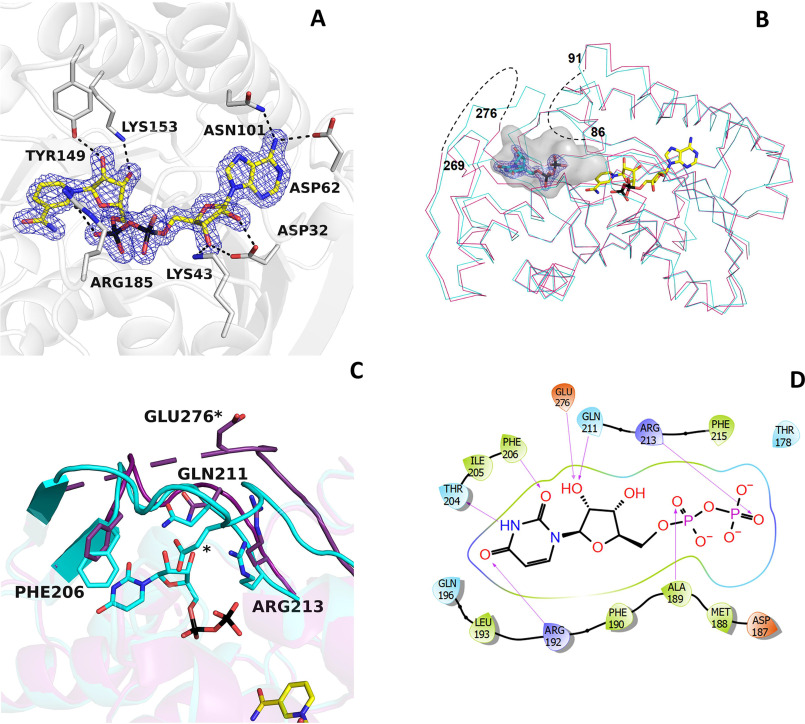

Figure 2.

NAD+ and UDP binding in BcUGAepi. A, weighted 2Fo − Fc electron density of NAD+ in the epimerase/NAD+ binary complex (subunit A). The contour level is 1.4σ. Side chains involved in hydrogen-bonding and electrostatic interactions are shown (light gray carbons). Together with Thr-126 (Fig. 3), Tyr-149, and Lys-153 are part of the fingerprint catalytic triad of the SDR family. B, superposition between the Cα traces of the epimerase structures bound to NAD+ (purple) and NAD+/UDP (cyan). NAD+ carbons are shown in yellow, and UDP carbons are shown in cyan. The electron density of UDP is shown with a contour level of 1.4σ. The loops 86–91 and 269–276 are disordered in the NAD+ complex (dashed lines). Upon UDP binding, both loops adopt an ordered conformation that defines a large cavity where the mononucleotide ligand binds. The large cavity space between the UDP pyrophosphate and the nicotinamide forms the sugar-binding site. C, ribbon diagram of the NAD+ structure (purple) superposed onto the complex with NAD+/UDP (cyan). In the absence of UDP, loop 269–276 is disordered. UDP binding reorganizes this loop that, together with residues 204–214, wraps the UDP molecule. D, two-dimensional schematic diagram of the extensive interactions between UDP and the protein residues.

On the structural roles of UDP

In the NAD+ complex, two loops around the catalytic site (residues 86–91 and 269–276) are disordered as gathered from the absence of well-defined electron density around them (Fig. 2B). The crystal structure of the enzyme bound to UDP (1.7 Å resolution; Table 1) reveals that these two loops become ordered in the presence of the nucleotide diphosphate. In particular, Glu-276 anchors the hydroxyl groups of the nucleotide ribose, whereas loop 86–91 lends more rigidity to the part of the cavity hosting the pyrophosphate (Fig. 2, B and C). UDP binding affects the conformation of a third loop, formed by residues 204–214. This loop moves closer to the UDP-binding site so that Gln-211 and Arg-213 can hydrogen-bond to the UDP's ribose hydroxy groups and the β-phosphate, respectively. Moreover, Phe-206 is implicated in π-stacking with the uracil ring, whereas Thr-204 is hydrogen-bonded to the NH group of the base. This complex network of UDP-protein interactions is completed by loop 187–196. Here, Arg-192 is engaged in a hydrogen bond with the uracil, whereas the backbone N atom of Ala-189 is hydrogen-bonded to the UDP pyrophosphate (Fig. 2D). Unlike residues 86–91, 204–214, and 269–276, the conformation of loop 187–196 remains unaltered upon UDP ligation, being the only element of the apoenzyme that is already preorganized for nucleotide binding. These findings highlight the role of the UDP moiety of the sugar nucleotide substrate. In the apoenzyme, the binding site is open and can be readily accessed. With its many hydrogen-binding groups, UDP triggers a few localized structural changes that collectively create the cavity where the sugar group binds and is modified (Fig. 2B). The nucleotide group of the substrate is therefore necessary to attain the catalytically competent conformation of the active site.

Structure of the Michaelis complex

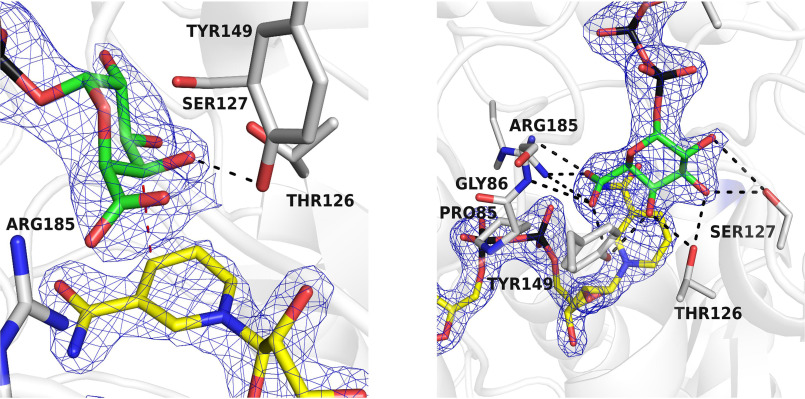

The active site is located at the interface between the NAD+ and the UDP domains (29–31). To visualize the mode of the sugar binding in this cavity, BcUGAepi was co-crystallized in the presence of an excess of UDP-GlcA, and the structure was solved at 1.8 Å resolution (Table 1). The electron density map shows the conformations of the sugar and nearby nicotinamide conformation with excellent clarity (Fig. 3, A and B). In solution, the equilibrium of the reaction [UDP-GalA]/[UDP-GlcA] is 2.0 as measured using 1 mm UDP-GlcA at pH 7.6 (23). We hypothesize that crystal packing and the higher viscosity of the crystallization solutions, due to the relatively high PEG3350 concentrations (∼20%, w/v), may shift the equilibrium toward the substrate, UDP-GlcA. The glucuronic acid faces the nicotinamide ring of NAD+ with a geometry that is perfectly suited for the hydride transfer and 4-keto-hexose-uronic acid intermediate generation (Scheme 1). As observed in MoeE5 (22), the sugar adopts the chair conformation to position its 4′-carbon at 3.2 Å from the C4 atom of the NAD+. The substrate 4′-H atom is thereby predicted to point exactly toward the C4 of the nicotinamide ring (Fig. 3A). Moreover, Tyr-149 properly interacts with the substrate to afford the deprotonation of the 4′-OH group (11). In essence, the co-crystallization experiment allowed us to capture the fine geometry of substrate binding in the Michaelis complex.

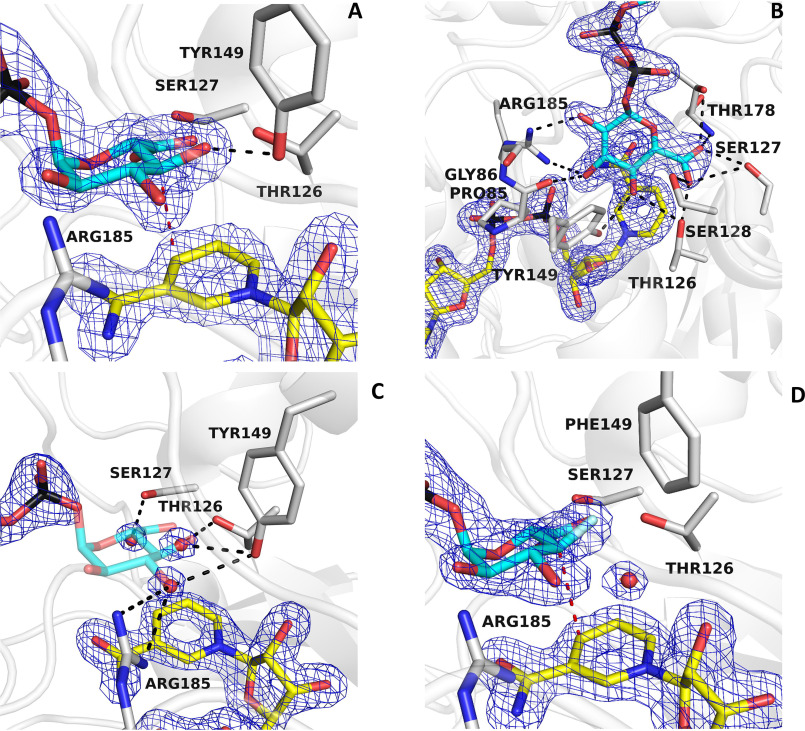

Figure 3.

Binding of UDP-glucuronic acid. A and B, binding of the sugar moiety of the substrate (cyan carbons) in two orientations. The weighted 2Fo − Fc electron density for the NAD+ (yellow carbons) and substrate is contoured at 1.4σ (subunit A). The orientation of A outlines the binding of the substrate C4′ at 3.2 Å from C4 of the nicotinamide (red dashed line) and the hydrogen bond between the sugar O4′ and Tyr-149 (black dashed line). All hydroxyl groups and the carboxylate of the glucuronic acid are engaged in hydrogen-bonding interactions as shown in B. C, a cluster of ordered water molecules are bound in the sugar-binding site of the UDP/NAD+ complex. The positions of these waters exactly superpose onto the 3′-OH, 4′-OH, and 5′-carboxylate of the substrate sugar. The orientation is the same as in the left panel of A, and the contour level of the density is 1.4σ (subunit A). D, binding of UDP-4-deoxy-4-fluoro-α-d-glucuronic acid (fluorine in light cyan) to the Y149F mutant (subunit A). The structure is virtually identical to that of the ternary NAD+/UDP-glucuronic acid complex (Fig. 3A). The hydroxyl group of Tyr-149 is replaced by an ordered water molecule in contact with the fluorinated C4′ atom.

The sugar-binding cavity features a constellation of polar groups that are precisely positioned for hydrogen bonding to the hydroxy and carboxylate groups of the substrate (Fig. 3B). The 4′-OH engages two residues of the SDR catalytic triad (Thr-126 and Tyr-149), whereas the 2′-OH and 3′-OH are hydrogen-bonded to Arg-185 and Pro-85 (backbone oxygen). The 5′-carboxylate interacts with Thr-126, Ser-127, Ser-128, and Thr-178. Interestingly, Thr-178 is the only residue in a disallowed region of the Ramachandran plot in all substrate/product-bound structures. Strained conformations have been often observed in enzyme active sites (40). In BcUGAepi, this strained backbone conformation is involved in the binding of the substrate carboxylate group whose negative charge is critical for recognition specificity. Indeed, UDP-glucose, UDP-galactose, UDP-GlcNAc, and UDP-xylose are poorly active substrates or inactive against UDP-glucuronic acid 4-epimerases (19, 23, 41–43).

The comparison between the structures of the enzyme bound to UDP and UDP-GlcA shows an interesting feature that further highlights this perfect complementarity between the sugar and its binding site. In the UDP complex, the sugar cavity is occupied by three ordered water molecules whose positions exactly overlap the 3′-OH, 4′-OH, and 5′-carboxylate groups of the substrate (Fig. 3C). Thus, the polar groups that decorate the cavity surface define a set of polar niches whose spacing matches the geometry of the polar substituents on the chair conformation of the glucuronic acid substrate.

These structural features were further explored in an experiment that probed the interactions at the 4′-OH locus of the substrate. The low-activity Y149F mutant (23) was co-crystallized with UDP-4-deoxy-4-fluoro-α-d-glucuronic acid, an inert substrate analog where the 4′-OH is replaced by a fluorine atom. The structure (1.7 Å resolution; Table 1) shows the sugar ring with the same orientation and interactions as described previously with the UDP-GlcA structure (Fig. 3D). The 4′-carbon is at a slightly longer distance from the C4 of the nicotinamide (3.5 Å versus 3.2 Å observed in the substrate complex). Interestingly, the Y149F replacement gives room for the binding of an ordered water molecule that is absent in the structure of the WT protein. Possibly, this water molecule may take over the role of the Tyr-149 hydroxyl group, explaining the residual, yet significant, activity of this mutant (23). Besides this variation in the water structure, the conformation of the active site, including the side chain at position 149, is essentially identical to that observed in the WT and remains unaffected by the mutation. These observations validate the conclusions inferred from the analysis of the UDP-GlcA complex and confirm that the OH group of the strictly conserved Tyr-149 is above all critical for its role in acid-base catalysis (44, 45), whereas it has little impact on the active-site and sugar conformation.

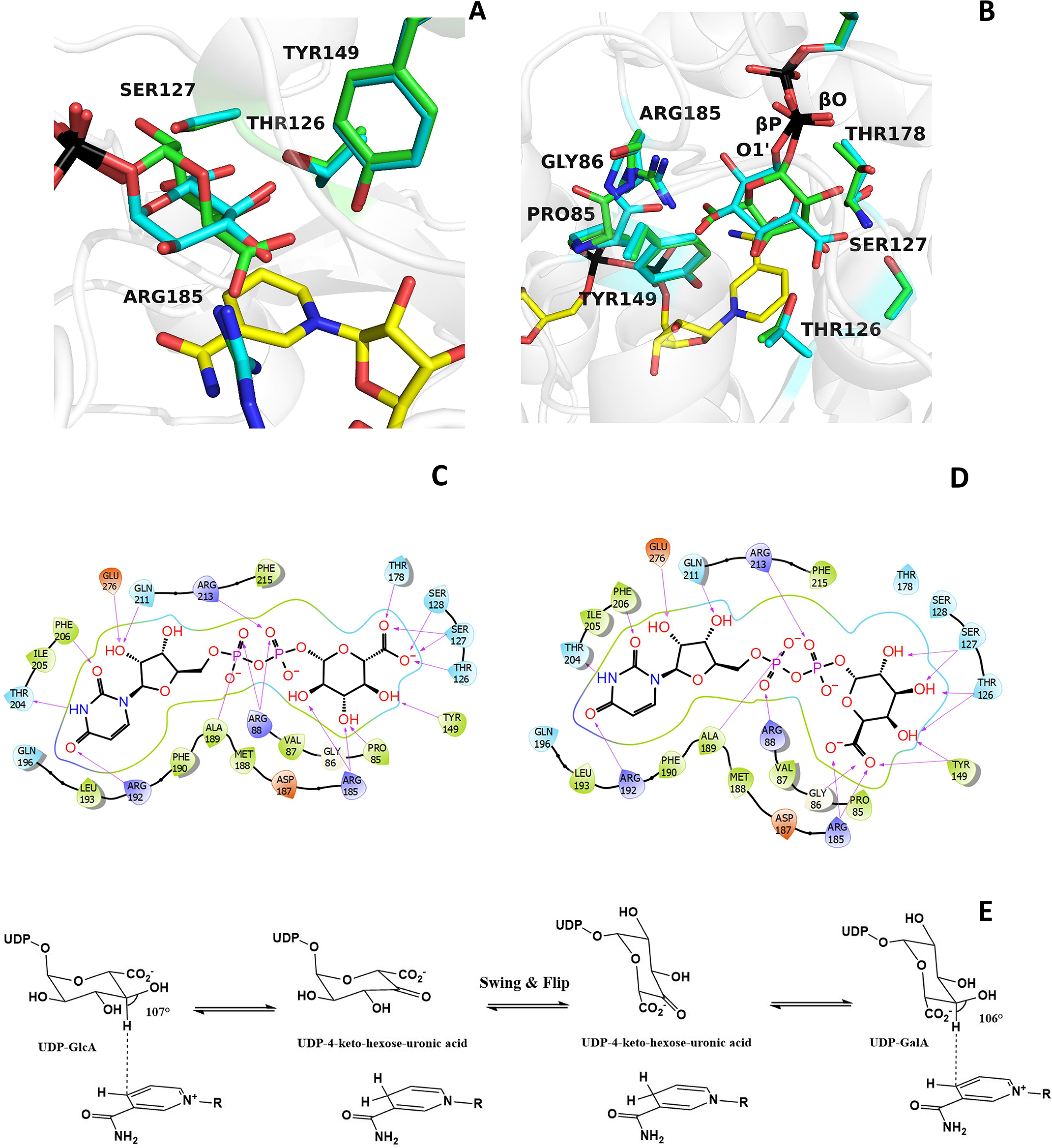

Capturing the rotation of the 4-keto-hexose-uronic acid intermediate

After the UDP-GlcA substrate is oxidized by NAD+ (which is reduced to NADH), the 4-keto-hexose-uronic acid is thought to rotate inside the active site to favor the hydride transfer from NADH to the opposite face of the intermediate, therefore inverting the configuration of the C4′ (see Scheme 1). To obtain evidence of this rotation mechanism, we co-crystallized BcUGAepi with an excess of the UDP-GalA product (1.5 Å resolution; Table 1). The multiple X-ray diffraction data sets collected on several crystals grown in these conditions consistently led to electron density maps that were distinctly different from that observed in the substrate-bound enzyme. The maps could not be satisfactorily explained by the presence of a bound UDP-GalA, as both modeling and crystallographic refinement systematically suggested the presence of residual density that could not be accounted for by the ligand. After various modeling experiments, we came to the conclusion that this extra density must be ascribed to a glucuronic acid molecule. In the course of crystallization, UDP-GalA is partly converted to UDP-GlcA so that the crystals contain an approximately equimolar content of GalA- and GlcA-bound crystalline enzymes (refined occupancies 0.5/0.5; Fig. 4 (A and B)). This observation is line with the above-discussed idea that the crystallization conditions likely favor substrate accumulation. We define this complex as an “equilibrium” structure that is extremely interesting to visualize the start and end points of the reaction. Above all, this structure immediately suggests that the sugar rings of substrate and product bind with opposite orientations within the active site. Moreover, it reveals that ligand flipping can take place with almost no changes in the active site because the conformation of the equilibrium structure turned out to be virtually identical to that of the UDP-GlcA complex.

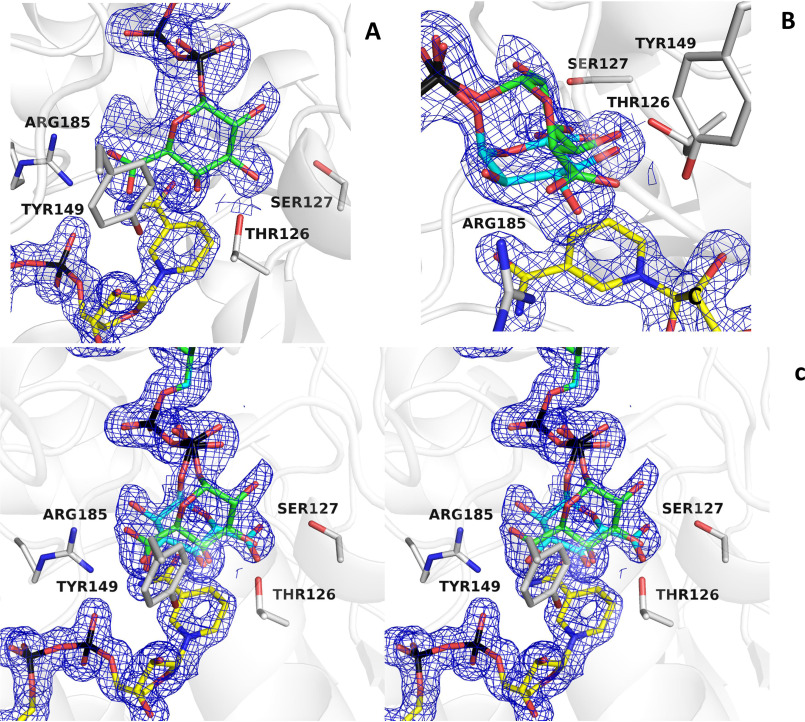

Figure 4.

The equilibrium structure shows how the same active-site conformation accommodates substrate and product with their opposed chirality. A, the weighted 2Fo − Fc map obtained from crystals grown in the presence of UDP-GalA can be nicely fit by this sugar (green carbons), but a significant portion of the density remains unoccupied (contour level 1.4σ; subunit A). B and C, fitting of galacturonic (green carbons) and glucuronic (cyan carbons) moieties (0.5/0.5 occupancies) into the electron density shown with the same orientation as in Fig. 3 (A and B). C is shown in stereoview.

To confirm these findings and obtain further insight into the geometry of product-binding orientation, we performed another crystallographic experiment to obtain the structure in complex with UDP-GalA alone. We reasoned that the ionizable group of Tyr-149 and its function as active-site base could be highly sensitive to pH. Moreover, lowering of the temperature could further modulate the enzyme reactivity. Therefore, we performed the co-crystallization experiments with UDP-GalA at a lower pH (6.5 instead of 8.0) and temperature (4 °C instead of 20 °C). This strategy proved to be successful in that the crystal structure (1.85 Å resolution; Table 1) reveals very clear and unambiguous density for the GalA product bound to the active site (Fig. 5). Moreover, the GalA-binding mode exactly matches that observed in the equilibrium structure, whose interpretation was thereby further validated by this experiment. The sugar of the UDP-GalA is flipped with respect to the orientation of the sugar of UDP-GlcA and is implicated in an intricate network of interactions. The three hydroxy groups in positions 1′, 2′, and 3′ are hydrogen-bonded to Ser-127, Thr-126, and Tyr-149, whereas the 5′-carboxylate is hydrogen-bonded to Tyr-149, Gly-86 (backbone N atom), and Arg-185. Clearly, the BcUGAepi active site can satisfy the hydrogen-bonding propensity of all polar (OH and carboxylate) groups of the sugar product despite its flipped orientation with respect to the substrate.

Figure 5.

The crystal structure of BcUGAepi in complex with NAD+ and UDP-galacturonic acid at pH 6.5 and 4 °C shown in two different orientations. The left panel highlights the position of the C4′ in proximity of the nicotinamide (red dashed line) and the hydrogen bond between the sugar O4′ and Tyr-149 (black dashed line). As shown in the right panel, all hydroxyl groups and the carboxylate of the glucuronic acid are engaged in hydrogen-bonding interactions with the protein. The orientations are the same as in Fig. 3 (A and B). The contour level of the weighted 2Fo − Fc density is 1.4σ (subunit A).

The superposition of BcUGAepi/NAD+/substrate and BcUGAepi/NAD+/product complexes is particularly helpful in delving into these findings. The two complexes are nearly identical with a root mean square deviation of 0.33 Å for their α-carbons. Likewise, the binding of the UMP moiety of UDP-GalA is identical to that observed in the UDP-GlcA complex. Critical differences are instead observed for the β-phosphate and the sugar rings (Fig. 6, A and B). Small 20–30° torsional rotations about the pyrophosphate's P–O–P bonds shift by 0.2 Å the position of the O1′ atom bound to the β-phosphorus. This movement is coupled to a 160° rotation about the O1′–C1′ bond that flips the sugar ring. Such a “swing and flip” movement reorients and repositions the sugar within the large active-site cavity (Video S1). Despite such a drastic alteration, both product and substrate sugars retain the same chair conformation. The positions of the 3′-OH, 4′-OH, and 5′-carboxylate substituents of the glucuronic acid substrate overlap with those of the 5′-carboxylate, 4′-OH, and 3′-OH substituents of the galacturonic acid product (Fig. 6, B–D). Strikingly, the C4′ atom of UDP-GlcA and UDP-GalA holds exactly the same position at 3.2 Å from NAD+ with the C4nicotinamide–C4′sugar–O4′sugar angle measuring 106–107° in both structures (Fig. 6E). The only protein conformational change affects the peptide bond between Pro-85 and Gly-86 that has flipped orientation in the two structures; Pro-85 oxygen (main chain) interacts with the 3′-OH of the substrate, whereas Gly-86 (main chain) interacts with the 5′-carboxylate of the product (Fig. 6C). Based on these observations, we surmise that after UDP-GlcA oxidation, the suboptimal interactions of the more rigid and distorted structure of the 4-keto-hexose-uronic intermediate promotes the swing and flip movement that is coupled to the flipping of the 85-86 peptide bond. The salt bridge between Arg-185 and the flipped 5′-carboxylate may be critical for holding the rotated intermediate and prevent its decarboxylation (Fig. 6, B and D). With a firm grip on the flipped sugar, NADH can transfer its 4-hydride to the C4′ of the keto intermediate affording the chirally inverted product.

Figure 6.

A detailed comparison of UDP-glucuronic and UDP-galacturonic acid binding. A and B, the galacturonic acid (green carbons) can be moved on top of the glucuronic acid (cyan carbons) through a rotation of about 160° around the bond between the β-phosphorus (βP) of UDP and O1′ of the sugar combined with a smaller “swinging” 30° rotation around the bond between the β-phosphorus and the pyrophosphate oxygen (βO) of UDP. These movements can be best-appreciated in the orientation of the right panel. The orientations are the same as in Fig. 3 (A and B). C and D, schematic two-dimensional overviews of the protein-ligand interactions. Despite their differing swing-rotated orientations, both sugars engage their polar groups in multiple hydrogen bonds with protein side chains. Only the 2′-carbon of glucuronic acid (B) is not hydrogen-bonded to the protein as it interacts with ordered waters. Moreover, the conformations of all active-site side chains remain virtually unaltered in the two complexes. E, scheme of the BcUGAepi reaction. The fine geometry of the C4′sugar–C4nicotinamide contact allows C4′ oxidation of glucuronate (forward reaction) and galacturonate (reverse reaction) acid.

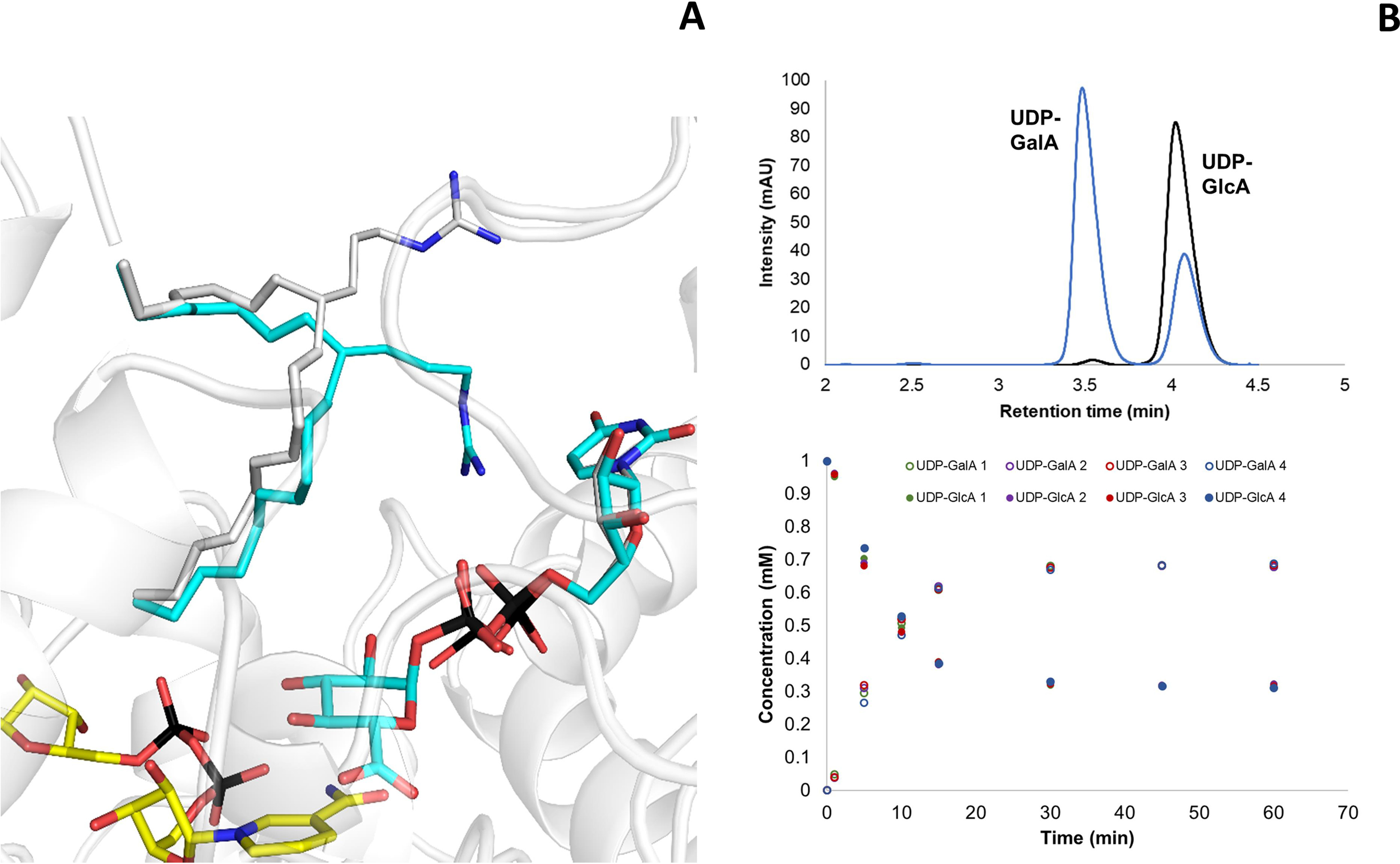

A flexible UDP-binding arginine promotes catalysis

Besides the highly ordered conformation of the active site as revealed by the crystal structure of the substrate and product complexes, the epimerization mechanism inherently entails a considerable degree of malleability of the active site to allow both UDP-GlcA binding and rotation of the keto intermediate. In this context, we were intrigued by the role of Arg-88 at the entrance of the active site. This arginine residue is present only in BcUGAepi and MoeE5 (Arg-94) (22). Other epimerases, such as UDP-galactose 4-epimerase (21, 29–31, 36), have a glycine residue, whereas other SDR decarboxylases (e.g. UAXS in Scheme 1 (16)) show an alanine in the same position. Arg-88 belongs to one of the above-described loops that become ordered only upon UDP binding (loop 86–91; see Fig. 2B). In the presence of glucuronic acid, the loop moves even closer to the UDP, and the side chain swings into the active site, interacting with the pyrophosphate and optimizing the shape of the substrate cavity (Fig. 7A). We hypothesized that this loop, with its multiple discrete conformations, could be instrumental to substrate binding and intermediate rotation occurring during catalysis. We therefore studied the R88A mutation that removes the long and flexible side chain at this position. The mutant enzyme was found to retain the capacity to generate UDP-GalA but with an 8-fold lower catalytic rate (0.032 ± 0.002 s−1; Fig. 7B) compared with 0.25 ± 0.01 s−1 of the WT enzyme (23). We then turned to the kinetic isotope effect (kcatH/kcatD) to probe the effects of the mutation using a C4′-deuterated substrate. We have previously shown that WT BcUGAepi shows a relatively low kcatH/kcatD of 2.0 ± 0.1, due to a slow catalytically relevant conformational change that partially masks the kinetic isotope effect (23). Conversely, we found that the R88A protein displays a more pronounced kcatH/kcatD of 4.2 ± 0.3, a typical value for hydride transfer reactions. These data hint at a combination of factors affecting the properties of R88A. In the mutant, the suboptimal position of the glucuronic acid substrate may impair hydride transfer, whereas the more spacious and flexible active site can be less limiting for catalysis. As a result, the kinetic isotope effect appears to be largely unmasked in the mutant protein.

Figure 7.

The role of Arg-88. A, in the presence of UDP-GlcA, loop 85–90 (shown as Cα trace; subunit A) closes over the substrate (cyan carbons), shifting its position as compared with the structure of the UDP-bound enzyme (gray carbons; subunit A). In particular, Arg-88 changes its conformation to interact with the UDP pyrophosphate. B, BcUGAepi R88A reaction with UDP-GlcA as substrate. The reaction mixture contained 1 mm UDP-GlcA, 1 mm NAD+, and 27 μm (1 mg/ml) purified recombinant BcUGAepi R88A in sodium phosphate buffer (50 mm Na2HPO4, 100 mm NaCl, pH 7.6) in a final volume of 200 µl. The HPLC chromatograms after 1 min (black) and 60 min (blue) from the start of the reaction are shown in the top panel. The bottom panel depicts the time course of the depletion of UDP-GlcA (filled circles) and formation of UDP-GalA (open circles). Reactions were performed in quadruplicate, and all of the individual data points are shown.

Conclusion

Our work illuminates many aspects of the epimerization reaction catalyzed by UDP-GlcA epimerases. NAD+ is fully embedded within the protein, functioning as nondissociable prosthetic group. Conversely, the substrate-binding site is lined by a set of flexible loops and side chains. Only upon UDP binding, these loops become ordered to create a cavity in front of the nicotinamide ring. The nucleotide component of the substrate is therefore necessary for attaining the catalytically competent conformation. The active-site geometry features an exquisite complementarity to the sugar substrate. All of the hydrogen-bonding groups of the glucuronic acid find a polar counterpart. Moreover, the 4′-carbon undergoing epimerization is precisely oriented for transferring a hydride to the nicotinamide. With its trigonal carbon, the resulting 4-keto-hexose-uronic acid intermediate may experience suboptimal fitting and interactions inside the cavity. Through a swing and flip movement, the intermediate eventually rotates in the active site (Video S1 and Fig. 6E). The spacious cavity of the enzyme is instrumental to this process. Consistently, its volume measures 990 Å3 which is almost double that of the UDP-xylose and UDP-apiose/xylose synthases (500–600 Å3; Fig. 8). Moreover, the very same loops that allow UDP-GlcA binding and active-site closure are likely to confer the malleability required for the intermediate rotation. The experiments on Arg-88 support this notion. The flipped orientation positions the carbonyl group of the intermediate exactly as needed for the efficient hydride transfer from NADH, which ultimately generates the chirally inverted UDP-galacturonic acid product. Strikingly, the same active-site configuration of the substrate complex (with only the exception of a peptide flip) is retained in the product complex. All polar groups of the galacturonic acid are indeed engaged in hydrogen-bond interactions with the protein. This feature explains why the enzyme can also catalyze the reverse reaction, namely the epimerization of UDP-galacturonic acid to UDP-glucuronic acid. Moreover, these precisely arranged hydrogen bond interactions guarantee that the reactive keto intermediate is protected from the facile decarboxylation, differently from similar enzymes that modify UDP-GlcA through its decarboxylation.

Figure 8.

Comparison between the UGP-glucuronic binding sites of B. cereus epimerase (left) and A. thaliana UDP-apiose/UDP-xylose synthase (right, PDB entry 6H0N). The two enzymes share the same short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase site and catalytic (Ser/Thr-Tyr-Lys) triad. However, their sugar cavities have different shapes. The more spacious site of the epimerase is instrumental to a swing-rotation conformational change that the sugar undergoes after oxidation by NAD+.

Experimental procedures

Materials

All chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich, unless otherwise stated. The synthetic gene encoding for BcUGAepi was ordered in pET17b-expression vector (pET17b_BcUGAepi) from GenScript as a codon-optimized gene for optimal expression in E. coli and with C-terminal Strep-tag for protein purification. For plasmid DNA isolation, the GeneJET Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used. DpnI and Q5® High-Fidelity DNA polymerase were from New England Biolabs (Frankfurt am Main, Germany). Oligonucleotide primers were from Sigma–Aldrich. E. coli NEB5α competent cells were from New England Biolabs. E. coli Lemo21(DE3) cells were prepared in-house. DNA sequencing was performed by GATC (Konstanz, Germany). UTP (98% purity) and ATP (98% purity) were purchased from Carbosynth (Compton, UK). Deuterium oxide (99.96% 2H) was from Euriso-Top (Saint-Aubin Cedex, France). Calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase was from New England Biolabs, and d-lactate dehydrogenase was from Megazyme (Vienna, Austria). Albumin Fraktion V (BSA) was from Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany). UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase, inorganic pyrophosphatase and human UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase were expressed and purified according to previously described protocols (23). GalKSpe4 was expressed following a protocol from the literature (46) and purified utilizing Strep-tag. UDP-galacturonic acid and UDP-4-[2H]glucuronic acid were synthesized as described previously (23). The synthesis of UDP-4-deoxy-4-fluoro-α-d-glucuronic acid (4F-UDP-glucuronic acid) is described in the supporting information (see Scheme S1 and Figs. S1–S4).

Site-directed mutagenesis

BcUGAepi_R88A and BcUGAepi_Y149F variants were prepared using a modified QuikChange protocol as described previously (23). PCRs were carried out in a reaction volume of 50 µl using 20 ng of plasmid DNA as template and 0.2 μm forward or reverse primer. Q5 DNA polymerase was used for DNA amplification.

Protein expression and purification

E. coli cells harboring pET17b_BcUGAepi (or pET17b_BcUGAepi_Y149F/pET17b_BcUGAepi_R88A) were grown in 10 ml of lysogeny broth medium (50 μg/ml ampicillin and 35 μg/ml chloramphenicol) at 37 °C for 16 h. 2 ml of preculture were used to inoculate fresh lysogeny broth medium (250 ml) supplemented with ampicillin (50 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (35 μg/ml), and the cells were grown at 37 °C and 120 rpm. When the cell density (A600) reached a value of 0.8, isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (0.2 mm) was added to the culture media to induce gene expression. The cells were incubated at 18 °C and 120 rpm for 20 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (2800 × g, 4 °C, 20 min), the pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of Strep-tag loading buffer (100 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, pH 8), and the suspension was stored overnight at −20 °C prior to cell lysis. The cells were disrupted by sonication (pulse 2 s on, 5 s off, 70% amplitude, 5 min) and centrifuged (16,100 × g) at 4 °C for 45 min. The supernatant was collected and filtered (0.45 μm) prior to loading onto the StrepTrapTM HP column (5 ml of resin, GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with the loading buffer (100 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, pH 8). The Strep-tagged protein was eluted with elution buffer (100 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm d-desthiobiotin, pH 8) and rebuffered against the reaction buffer (50 mm Na2HPO4, 100 mm NaCl, pH 7.6) containing 10% glycerol using Amicon filter tubes (30-kDa cut-off). After buffer exchange, the protein was divided into aliquots, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −20 °C. Protein concentration was determined based on the absorption at 280 nm on a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Size and purity of the protein were confirmed by SDS-PAGE.

X-ray crystallography

Purified BcUGAepi was concentrated at 11 mg ml−1 in 20 mm Tris-HCl buffer at pH 8, 50 mm NaCl. Crystallization screenings were performed by the vapor-diffusion sitting-drop technique using commercial kits (Jena Bioscience and Hampton Research) and an Oryx 8 crystallization robot (Douglas Instruments, East Garston, UK). Crystallization hits were optimized manually using the sitting-drop protocol. After optimization, the best-diffracting crystals were found in a condition containing 200 mm potassium acetate and 14–24% PEG 3350, and the protein was co-crystallized in the presence of 2 mm NAD+ and a 2 mm concentration of different UDP ligands (Table 1). Crystals grew in 48 h from drops prepared in a ratio of 1:1 BcUGAepi (11 mg ml−1) and reservoir at 20 °C. Crystals grown in the presence of NAD+/UDP-GalA were obtained at 4 °C using a BcUGAepi sample concentrated to 11 mg ml−1 in 20 mm Tris-HCl buffer at pH 6.5, 50 mm NaCl. Crystals were harvested from the mother liquor using nylon cryoloops (Hampton Research) and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen after a short soak in a solution containing 26% (v/v) PEG 3350, 200 mm potassium acetate, 20% (w/v) glycerol, 2 mm NAD+, and 2 mm ligand. X-ray diffraction data used for structure determination and refinement were collected at the PX beamline of the Swiss Light Source in Villigen, Switzerland. Data were scaled using the XDS (47) program and CCP4 (25) package for indexing and processing of the data. The space group symmetry together with final data collection and processing statistics are listed in Table 1. The initial structure (NAD+ complex) was solved with MOLREP (48) using the coordinates of NAD-dependent epimerase from Klebsiella pneumoniae (PDB entry 5U4Q) as a search model. Manual building, the addition of water molecules, and crystallographic refinement were performed with COOT (49), REFMAC5 (50), and other programs of the CCP4 suite. Hydrogen atoms were added in the riding position following REFMAC5 protocols. Structure quality and validation were assessed using the wwPDB validation server. Figures were created with PyMOL (51) and Maestro (release 2020-1) of the Schrödinger suite of programs, whereas cavity size was measured with Caver (52). Hydrogen bonds were inferred with Maestro using the default parameters (Schrödinger).

Activity assays

The reaction mixture (200-µl final volume) contained 1 mm UDP-GlcA, 1 mm NAD+, and 27 μm (1 mg/ml) purified recombinant BcUGAepi R88A in sodium phosphate buffer (50 mm Na2HPO4, 100 mm NaCl, pH 7.6). The reaction was incubated at 23 °C and quenched with methanol (50% (v/v) final concentration) at desired time points, and the precipitated enzyme was removed by centrifugation (16,100 × g, 4 °C, 30 min) prior to HPLC analysis. The initial rate was determined from the linear part of the time course by dividing the slope of the linear regression (mm/min) by the enzyme concentration (mg ml−1), giving the initial rate in µmol/(min mg protein). The apparent kcat value (s−1) was calculated as an average of four independent experiments from the initial rate with the molecular mass of the functional enzyme monomer (BcUGAepi R88A: 36,918 g/mol).

Kinetic isotope effect measurement

The sugar nucleotides UDP-GlcA and UDP-GalA were separated with the Shimadzu Prominence HPLC-UV system (Shimadzu, Korneuburg, Austria) on a Kinetex C18 column (5 μm, 100 Å, 50 × 4.6 mm) using an isocratic method with 5% acetonitrile and 95% tetrabutylammonium bromide buffer (40 mm tetrabutylammonium bromide, 20 mm K2HPO4/KH2PO4, pH 5.9) as mobile phase. UDP-sugars were detected by UV at 262-nm wavelength. For kinetic isotope effect measurements, a BcUGAepi concentration of 0.1 mg ml−1 (2.7 μm) was used, and the reactions (30-µl final volume) were performed in quintuplicates for both UDP-GlcA and 4-2H-UDP-GlcA (1 mm). The reaction mixtures were quenched (incubation in 50% (v/v) methanol) after 5 min and analyzed on HPLC. Initial reaction rates (V) were calculated from the linear dependence of the product formed and time used. The kinetic isotope effect was calculated from the ratio of the reaction rates (effectively kcat) for the unlabeled and deuterium-labeled substrate (KIE = Vunlabeled/Vlabeled).

Data availability

The structures presented in this paper have all been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with the codes 6ZLA, 6ZL6, 6ZLD, 6ZLK, 6ZLJ, and 6ZLL. All remaining data are contained within the article.

Supplementary Material

This article contains supporting information.

Author contributions—L. G. I., A. J. B., B. N., and A. M. conceptualization; L. G. I., S. S., and A. J. B. investigation; L. G. I., S. S., A. J. B., and B. N. methodology; L. G. I. and A. M. writing-original draft; A. J. B., C. B., and A. M. validation; A. J. B., B. N., and A. M. writing-review and editing; C. B., B. N., and A. M. supervision; B. N. and A. M. funding acquisition.

Funding and additional information—This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economy (BMWFW), the Federal Ministry of Traffic, Innovation, and Technology (bmvit), the Styrian Business Promotion Agency SFG, the Standortagentur Tirol, and the Government of Lower Austrian and Business Agency Vienna through the COMET-Funding Program managed by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency FFG. This work was also supported by Austrian Science Funds (FWF) Grant I-3247 (to B. N. and A. J. E. B.) and by the Italian Ministry of Education, University, and Research (MIUR): Dipartimenti di Eccellenza Program (2018–2022)–Department of Biology and Biotechnology “L. Spallanzani” University of Pavia.

Conflict of interest—The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- SDR

- short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase

- BcUGAepi

- UDP-glucuronic acid 4-epimerase from Bacillus cereus

- UDP-GlcA

- UDP-glucuronic acid

- UDP-GalA

- UDP-galacturonic acid

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank.

References

- 1. Bethke G., Thao A., Xiong G., Li B., Soltis N. E., Hatsugai N., Hillmer R. A., Katagiri F., Kliebenstein D. J., Pauly M., and Glazebrook J. (2016) Pectin biosynthesis is critical for cell wall integrity and immunity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 28, 537–556 10.1105/tpc.15.00404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reboul R., Geserick C., Pabst M., Frey B., Wittmann D., Lütz-Meindl U., Leonard R., and Tenhaken R. (2011) Down-regulation of UDP-glucuronic acid biosynthesis leads to swollen plant cell walls and severe developmental defects associated with changes in pectic polysaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 39982–39992 10.1074/jbc.M111.255695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reiter W. D. (2008) Biochemical genetics of nucleotide sugar interconversion reactions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 236–243 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bowles D., Lim E. K., Poppenberger B., and Vaistij F. E. (2006) Glycosyltransferases of lipophilic small molecules. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57, 567–597 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Radominska-Pandya A., Little J. M., and Czernik P. J. (2001) Human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B7. Current drug metabolism 2, 283–298 10.2174/1389200013338379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ritter J. K. (2000) Roles of glucuronidation and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases in xenobiotic bioactivation reactions. Chem. Biol. Interact. 129, 171–193 10.1016/S0009-2797(00)00198-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Creuzenet C., Belanger M., Wakarchuk W. W., and Lam J. S. (2000) Expression, purification, and biochemical characterization of WbpP, a new UDP-GlcNAc C4 epimerase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa serotype O6. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 19060–19067 10.1074/jbc.M001171200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kelleher W. J., and Grisebach H. (1971) Hydride transfer in the biosynthesis of uridine diphospho-apiose from uridine diphospho-d-glucuronic acid with an enzyme preparation of Lemna minor. Eur. J. Biochem. 23, 136–142 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1971.tb01600.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moriarity J. L., Hurt K. J., Resnick A. C., Storm P. B., Laroy W., Schnaar R. L., and Snyder S. H. (2002) UDP-glucuronate decarboxylase, a key enzyme in proteoglycan synthesis: cloning, characterization, and localization. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 16968–16975 10.1074/jbc.M109316200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Neufeld E. F., Feingold D. S., and Hassid W. Z. (1958) Enzymatic conversion of uridine diphosphate d-glucuronic acid to uridine diphosphate galacturonic acid, uridine diphosphate xylose, and uridine diphosphate arabinose1,2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80, 4430–4431 10.1021/ja01549a089 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kavanagh K. L., Jörnvall H., Persson B., and Oppermann U. (2008) Medium- and short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase gene and protein families: the SDR superfamily: functional and structural diversity within a family of metabolic and regulatory enzymes. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 65, 3895–3906 10.1007/s00018-008-8588-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Allard S. T., Giraud M. F., and Naismith J. H. (2001) Epimerases: structure, function and mechanism. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 58, 1650–1665 10.1007/PL00000803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eixelsberger T., Sykora S., Egger S., Brunsteiner M., Kavanagh K. L., Oppermann U., Brecker L., and Nidetzky B. (2012) Structure and mechanism of human UDP-xylose synthase: evidence for a promoting role of sugar ring distortion in a three-step catalytic conversion of UDP-glucuronic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 31349–31358 10.1074/jbc.M112.386706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gatzeva-Topalova P. Z., May A. P., and Sousa M. C. (2005) Structure and mechanism of ArnA: conformational change implies ordered dehydrogenase mechanism in key enzyme for polymyxin resistance. Structure 13, 929–942 10.1016/j.str.2005.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Samuel J., and Tanner M. E. (2002) Mechanistic aspects of enzymatic carbohydrate epimerization. Nat. Prod. Rep. 19, 261–277 10.1039/b100492l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Savino S., Borg A. J. E., Dennig A., Pfeiffer M., de Giorgi F., Weber H., Dubey K. D., Rovira C., Mattevi A., and Nidetzky B. (2019) Deciphering the enzymatic mechanism of sugar ring contraction in UDP-apiose biosynthesis. Nat. Catal. 2, 1115–1123 10.1038/s41929-019-0382-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thibodeaux C. J., Melançon C. E., and Liu H. W. (2007) Unusual sugar biosynthesis and natural product glycodiversification. Nature 446, 1008–1016 10.1038/nature05814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thoden J. B., Henderson J. M., Fridovich-Keil J. L., and Holden H. M. (2002) Structural analysis of the Y299C mutant of Escherichia coli UDP-galactose 4-epimerase: teaching an old dog new tricks. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 27528–27534 10.1074/jbc.M204413200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Frirdich E., and Whitfield C. (2005) Characterization of Gla(KP), a UDP-galacturonic acid C4-epimerase from Klebsiella pneumoniae with extended substrate specificity. J. Bacteriol. 187, 4104–4115 10.1128/JB.187.12.4104-4115.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holden H. M., Rayment I., and Thoden J. B. (2003) Structure and function of enzymes of the Leloir pathway for galactose metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 43885–43888 10.1074/jbc.R300025200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thoden J. B., Wohlers T. M., Fridovich-Keil J. L., and Holden H. M. (2001) Human UDP-galactose 4-epimerase: accommodation of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine within the active site. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 15131–15136 10.1074/jbc.M100220200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sun H., Ko T. P., Liu W., Liu W., Zheng Y., Chen C. C., and Guo R. T. (2020) Structure of an antibiotic-synthesizing UDP-glucuronate 4-epimerase MoeE5 in complex with substrate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 521, 31–36 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.10.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Annika J. E., Borg A. D., Weber H., and Nidetzky B. (2020) Mechanistic characterization of UDP-glucuronic acid 4-epimerase. FEBS J. 10.1111/febs.15478 10.1111/febs.15478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eixelsberger T., Horvat D., Gutmann A., Weber H., and Nidetzky B. (2017) Isotope probing of the UDP-apiose/UDP-xylose synthase reaction: evidence of a mechanism via a coupled oxidation and aldol cleavage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 56, 2503–2507 10.1002/anie.201609288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (1994) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 10.1107/s0907444994003112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Karplus P. A., and Diederichs K. (2012) Linking crystallographic model and data quality. Science 336, 1030–1033 10.1126/science.1218231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gatzeva-Topalova P. Z., May A. P., and Sousa M. C. (2004) Crystal structure of Escherichia coli ArnA (PmrI) decarboxylase domain: a key enzyme for lipid A modification with 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose and polymyxin resistance. Biochemistry 43, 13370–13379 10.1021/bi048551f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Polizzi S. J., Walsh R. M. Jr., Peeples W. B., Lim J. M., Wells L., and Wood Z. A. (2012) Human UDP-α-d-xylose synthase and Escherichia coli ArnA conserve a conformational shunt that controls whether xylose or 4-keto-xylose is produced. Biochemistry 51, 8844–8855 10.1021/bi301135b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thoden J., Frey P., and Holden H. (1996) High-resolution X-ray structure of UDP-galactose 4-epimerase complexed with UDP-phenol. Protein Sci. 5, 2149–2161 10.1002/pro.5560051102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thoden J., Frey P., and Holden H. (1996) Molecular structure of the NADH/UDP-glucose abortive complex of UDP-galactose 4-epimerase from Escherichia coli: implications for the catalytic mechanism. Biochemistry 35, 5137–5144 10.1021/bi9601114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thoden J., Frey P., and Holden H. (1996) Crystal structures of the oxidized and reduced forms of UDP-galactose 4-epimerase isolated from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 35, 2557–2566 10.1021/bi952715y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jörnvall H., Persson B., Krook M., Atrian S., Gonzàlez-Duarte R., Jeffery J., and Ghosh D. (1995) Short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (SDR). Biochemistry 34, 6003–6013 10.1021/bi00018a001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Persson B., Kallberg Y., Bray J. E., Bruford E., Dellaporta S. L., Favia A. D., Duarte R. G., Jörnvall H., Kavanagh K. L., Kedishvili N., Kisiela M., Maser E., Mindnich R., Orchard S., Penning T. M., et al. (2009) The SDR (short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase and related enzymes) nomenclature initiative. Chem. Biol. Interact. 178, 94–98 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.10.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Holm L. (2019) Benchmarking fold detection by DaliLite v.5. Bioinformatics 35, 5326–5327 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu Y., Vanhooke J. L., and Frey P. A. (1996) UDP-galactose 4-epimerase: NAD+ content and a charge-transfer band associated with the substrate-induced conformational transition. Biochemistry 35, 7615–7620 10.1021/bi960102v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thoden J. B., and Holden H. M. (1998) Dramatic differences in the binding of UDP-galactose and UDP-glucose to UDP-galactose 4-epimerase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 37, 11469–11477 10.1021/bi9808969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jörnvall H. (1999) Multiplicity and complexity of SDR and MDR enzymes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 463, 359–364 10.1007/978-1-4615-4735-8_44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jörnvall H., Höög J.-O., and Persson B. (1999) SDR and MDR: completed genome sequences show these protein families to be large, of old origin, and of complex nature. FEBS Lett. 445, 261–264 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00130-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rossman M. G., Liljas A., Brändén C.-I., and Banaszak L. J. (1975) 2 Evolutionary and structural relationships among dehydrogenases. in The Enzymes (Boyer P. D., ed) pp. 61–102, Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 40. Herzberg O., and Moult J. (1991) Analysis of the steric strain in the polypeptide backbone of protein molecules. Proteins 11, 223–229 10.1002/prot.340110307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Broach B., Gu X., and Bar-Peled M. (2012) Biosynthesis of UDP-glucuronic acid and UDP-galacturonic acid in Bacillus cereus subsp. cytotoxis NVH 391-98. FEBS J. 279, 100–112 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08402.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gu X., and Bar-Peled M. (2004) The biosynthesis of UDP-galacturonic acid in plants: functional cloning and characterization of Arabidopsis UDP-d-glucuronic acid 4-epimerase. Plant Physiol. 136, 4256–4264 10.1104/pp.104.052365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Muñoz R., López R., de Frutos M., and García E. (1999) First molecular characterization of a uridine diphosphate galacturonate 4-epimerase: an enzyme required for capsular biosynthesis in Streptococcus pneumoniae type 1. Mol. Microbiol. 31, 703–713 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01211.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Berger E., Arabshahi A., Wei Y., Schilling J. F., and Frey P. A. (2001) Acid-base catalysis by UDP-galactose 4-epimerase: correlations of kinetically measured acid dissociation constants with thermodynamic values for tyrosine 149. Biochemistry 40, 6699–6705 10.1021/bi0104571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liu Y., Thoden J. B., Kim J., Berger E., Gulick A. M., Ruzicka F. J., Holden H. M., and Frey P. A. (1997) Mechanistic roles of tyrosine 149 and serine 124 in UDP-galactose 4-epimerase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 36, 10675–10684 10.1021/bi970430a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chen M., Chen L. L., Zou Y., Xue M., Liang M., Jin L., Guan W. Y., Shen J., Wang W., Wang L., Liu J., and Wang P. G. (2011) Wide sugar substrate specificity of galactokinase from Streptococcus pneumoniae TIGR4. Carbohydr. Res. 346, 2421–2425 10.1016/j.carres.2011.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kabsch W. (2010) XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 10.1107/S0907444909047337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vagin A., and Teplyakov A. (1997) MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30, 1022–1025 10.1107/S0021889897006766 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., and Cowtan K. (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 10.1107/S0907444910007493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Murshudov G. N., Skubák P., Lebedev A. A., Pannu N. S., Steiner R. A., Nicholls R. A., Winn M. D., Long F., and Vagin A. A. (2011) REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 355–367 10.1107/S0907444911001314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. DeLano W. L. (2012) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.5.0.1, Schrödinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chovancova E., Pavelka A., Benes P., Strnad O., Brezovsky J., Kozlikova B., Gora A., Sustr V., Klvana M., Medek P., Biedermannova L., Sochor J., and Damborsky J. (2012) CAVER 3.0: a tool for the analysis of transport pathways in dynamic protein structures. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002708 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The structures presented in this paper have all been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with the codes 6ZLA, 6ZL6, 6ZLD, 6ZLK, 6ZLJ, and 6ZLL. All remaining data are contained within the article.