Abstract

The current study used a nationally representative sample to investigate how older adults in China with different socio-demographic characteristics proactively sought support when social support of different sources and types was available; and whether the pattern of social support seeking varied with age, gender and regions. We found that older adults in China tended to seek social support from family members rather than from non-family members. Moreover, we observed a hierarchically ordered pattern of social support seeking within the family such that older adults preferred to first seek social support from a spouse and then turn to sons only when their spouse was unavailable or incapable of providing social support. We also observed a strong trend for son preferences in social support seeking, which was even more salient among old-old adults and older adults from rural China. The findings have implications for elder care and intergenerational support exchanges in Chinese societies.

Keywords: intergenerational support seeking, Socioemotional aging in China, Age, Gender, Region, Hierarchical compensatory model

Introduction

Literature has recognized social support as valuable resources to buffer stressors and enhance health (Cohen 2004; Umberson and Montez 2010). This is particularly true for older adults who may experience difficulties in handling life challenges by themselves while experiencing increasing declines in physical and cognitive health (Mao and Han 2018; White et al. 2009). Cross-cultural studies have observed that East Asians are more reluctant than Western counterparts to seek social support, especially from friends and neighbors (Kim et al. 2008; Taylor et al. 2004). However, relatively little is known about how people, especially East Asians, proactively enlist others for social support in everyday life (Dunkel Schetter 2017). The current study aimed to explore the pattern of social support seeking and the potential socio-demographic variations in a large-scale population-based sample of older adults in China.

Pattern of social support seeking among older adults in China

Socioemotional selectivity theory argues that older adults prioritize emotionally meaningful goals due to a limited time perspective (Carstensen 2006). From a cross-cultural perspective, individuals are socialized to engage in socioemotional activities in accordance with cultural values to fulfill emotionally meaningful goals (Fung 2013). Consistent with Confucian values of prioritizing family members (Liu et al. 2010), studies have found that older adults of Chinese origin: (1) showed a greater preference for interactions with emotionally close others (e.g., family members), (2) included nuclear family members and fewer acquaintances into their social networks and (3) trusted family members more than younger counterparts (Fung et al. 2001, 2008; Li and Fung 2013). Extending socioemotional selectivity theory to social support seeking, we propose that older adults in China may also seek social support of different types and sources in accordance with Chinese cultural values.

For centuries, Confucian ethics have served as moral and ethical guidelines for social conduct (Liu 2014). In the Confucian system of ethics, individuals are obligated to place family first and should support, protect and even shield family members unreservedly (Ward and Lin 2010). Within the family, father–son dyad is of the utmost importance throughout the life span, followed by elder brother–younger brother dyad and then husband–wife dyad (Yang 1993). As such, sons are preferred to carry on the family line and provide lifelong care for parents, but daughters bear the explicit responsibilities to assist their husbands to take care of parents-in-law (Cong and Silverstein 2008).

Nevertheless, Confucian cultural values have been revised at least to some extent in the processes of modernization, globalization and industrialization (Kulich and Zhang 2010). With the forces of social policies (e.g., one-child policy) and socio-demographic transitions (e.g., massive migration), traditional multigenerational families have fragmented into nuclear families, four grandparents–two parents–one-child families or empty-nest families, creating structural barriers for intergenerational support exchanges (Guo et al. 2009; Jiang and Sánchez-Barricarte 2011; Song et al. 2012). Similarly, traditional gender division of social support has also been somewhat revised with the importation of more egalitarian gender ideology: While sons continue to undertake the responsibility of supporting parents, daughters have begun to provide more social support to parents than in the past (Cong and Silverstein 2012; Song et al. 2012). Given the prioritization of family members in Chinese cultural values, older adults in China might seek social support from family members, primarily spouses or sons.

This supposition was demonstrated in previous studies of Chinese populations where the majority of older adults sought social support from family members, with adult children as the most cited sources of support among older adults in Taiwan and Mainland China (Dai et al. 2016; LaFave 2017). Other studies found that Mainland Chinese older adults identified spouses and sons as the major providers of support and reported sons as the more preferred source of support (Cong and Silverstain 2012; Li 1991; Sheng 2005).

Socio-demographic variations in social support seeking

Although people of Chinese origin generally seek support in accordance with cultural values, the pattern of support seeking may differ in subgroups with diverse socio-demographic characteristics because they may endorse cultural values as personal values to a different extent. In this study, we focused on whether and how the pattern of social support seeking differs by gender, age and region among older adults in China.

Gender is one salient determinant of social support seeking. Social support systems are gendered in most cultures for two primary reasons (Ajrouch et al. 2005; Fuller-Iglesias and Antonucci 2016). First, gender differences exist in the quantities and qualities of available support among older adults. Women tended to experience widowhood due to longer life expectancies (Utz et al. 2002). Women have larger social networks and received more support than men, with women having more emotionally close ties and men having more instrumental ties (e.g., coworkers) (Antonucci and Akiyama 1987; Fuhrer and Stansfeld 2002; Yeung et al. 2007). Second, older women and men differ in their preferences for support. Studies from Western countries show that older men report a spouse as the exclusive source of support, while older women seek support from multiple sources (e.g., children, friends) (Antonucci and Akiyama 1987; Cutrona 1996). Findings from a national representative sample showed that older men in China tended to receive care from spouses, but older women in China tended to receive care from children, especially when having no spouse (Chen et al. 2018). This suggests that gender may have a universal influence on social support systems cross-culturally.

The pattern of social support seeking may also differ by age. Evidence points to age differences in the endorsement of cultural values. Studies show that the endorsement of Confucian cultural values is positively associated with age among people of Chinese origin (Fung et al. 2011; Fung and Ng 2006). If Chinese do seek social support in accordance with cultural values, and the endorsement of cultural values intensifies with age, age might be positively associated with the tendency to seek social support from family members, especially a spouse or sons.

Moreover, the pattern of social support seeking may also differ by region. Two studies in the 1990s found that older adults in China from urban areas had begun to rely on spouses more and on children less relative to those from rural areas (Li 1991; Treas and Wang 1990). A recent study showed that older adults from Beijing sought social support following a hierarchical order of spouse, children and friends (Li et al. 2014). Findings from a national representative study indicated that older adults from rural China relied on adult children more relative to those from urban China (LaFave 2017).

Based on this review, only a few relatively small sample studies in the 1990s have examined the pattern of social support seeking among older adults in China, and these may not be representative of recent birth cohorts (Suanet and Antonucci 2016). Studies are also lacking that parse out preferred ways to seek social support versus the availability of social support. For these reasons, the goal of the present study was to reexamine the pattern of social support seeking and its variations in a recent population-based sample of older adults in China.

Given that Chinese cultural values prioritize family members, particularly the spouse and sons, over non-family members (Yang 1993), we hypothesized that older adults in China would seek social support from family members, especially the spouse or sons. Given that the endorsement of Confucian cultural values may vary across different socio-demographic subgroups, the above pattern of social support seeking may be more salient among men, older-old adults (aged 85 years or above) or adults from rural areas than among women, younger-old adults (aged less than 85 years) or adults from cities.

Method

Participants

This study utilized cross-sectional data from the 2011 wave of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS) (Center for Healthy Aging and Development Studies 2015). The CLHLS was a large-scale population-based longitudinal study of psychosocial and health characteristics of older adults randomly selected from 631 administrative districts in 22 provinces in China (Zeng 2008; Chen and Short 2008). The study received institutional review board approval from Wuhan University and obtained the permission for data use from the Center for Healthy Ageing and Development Studies at Peking University.

Measures

Social support seeking

Social support seeking was assessed by participants’ responses to three items: “the first person with whom you talk frequently in daily life,” “the first person with whom you talk when you need to tell someone about your thoughts” and “the first person you ask for help when you have problems.” For each item, the original response options were spouse, son, daughter, daughter-in-law, son-in-law, grandchildren and their spouses, other relatives, friends/neighbors, social workers, housekeepers and nobody. The responses were reduced to four categories: spouse, son and daughter-in-law, daughter and son-in-law, and others. We created a set of dichotomous variables (i.e., spouses, sons, daughters and others) to represent participants’ responses on each of the three items on social support seeking. For instance, when participants cited spouse as a source of social support on an item, the corresponding dichotomous variable (i.e., spouses) was coded as 1 and the other three dichotomous variables (i.e., sons, daughters and others) were coded as 0. Given the high correlation between the three items on social support seeking, we calculated the tendency of social support seeking from each source of support (e.g., spouse) by dividing the frequency of choosing the target source of support across all items on social support seeking by the number of items (i.e., 3).

Age-group Participants’ age was computed based on year of birth. Given that the sample included a larger portion of older adults aged over 75 years, we divided participants into young-old and old-old adults by the mean age of the sample (M = 85.78 years).

Gender Gender was coded by participants’ self-identification as male or female.

Region Participants reported their place of residence in terms of cities, towns and rural areas.

Marital status Participants reported their marital status as married and living together, separated, divorced, widowed or never married. We recoded married and living together and separated as having a spouse and all the other responses as not having a spouse.

Number of children Participants reported the numbers of sons and daughters currently alive.

Analysis design

To distinguish the tendency of social support seeking from the availability of social support, we created subgroups according to having a spouse, sons or daughters or not. We focused on subgroups with at least two sources of family support, but not those with one or no sources of family support. Given small sample sizes for some subgroups (Ndaughters and spouse = 159, Nsons and spouse = 365) and the fact that a large portion of participants had missing data on support (N = 2707), the final sample (N = 5176) only included subgroups with: (1) a spouse, sons and daughters (N = 2073) and (2) only sons and daughters (N = 3103).

SPSS version 23.0 was used for data analyses. A mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to reveal the different patterns of support seeking between the two subgroups, using subgroup as a between-subject variable and four sources of support as a within-subjective variable. Then, three parallel mixed-design analyses of variance were conducted to examine how the subgroup differences in social support seeking previously identified would be differed by socio-demographic variables (i.e., age-groups, gender and region). Specially, subgroup and socio-demographic variables were between-subject variables, source of support was the within-subject variable, and the tendency of social support seeking was the dependent variable. For all the analyses, statistical significance was set to p < .05.

Results

Descriptive statistics indicated that compared with older adults with a spouse, sons and daughters, older adults with sons and daughters only were older, included more females and had more sons. (For details, see Table 1.)

Table 1.

Characteristics of two subgroups of older adults in China with different sources of support

| Having a spouse, sons and daughters (N = 2073) | Having sons and daughters (N = 3103) | t/χ2 Tests | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 79.18 ± 8.29 | 89.17 ± 9.82 | 39.44*** |

| Gender (%) | 593.37*** | ||

| Male | 66.7 | 32.2 | |

| Female | 33.3 | 67.8 | |

| Region (%) | 1.74 | ||

| Cities | 21.0 | 19.7 | |

| Towns | 36.0 | 35.9 | |

| Rural areas | 43.0 | 44.4 | |

| Number of sons (mean ± SD) | 2.19 ± 1.31 | 2.27 ± 1.43 | 2.10* |

| Number of daughters (mean ± SD) | 2.15 ± 1.50 | 2.22 ± 1.33 | 1.31 |

*p value < .05, ***p value < .001

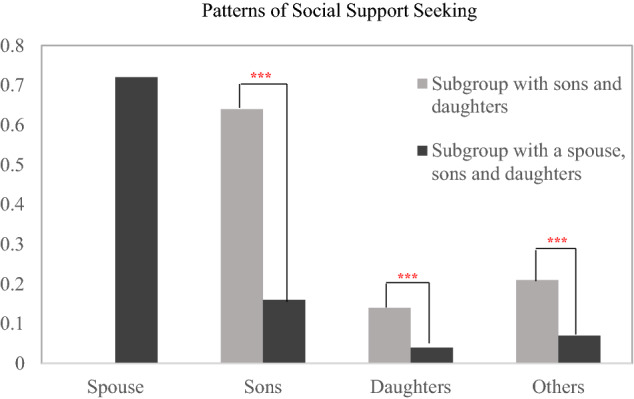

Results from the mixed-design ANOVA revealed a significant subgroup × source interaction effect on social support seeking, F (3, 15,204) = 3063.70, p < .001, η2 = .38. Further analyses revealed that source differences in social support seeking were stronger among older adults with a spouse, sons and daughters than among those with sons and daughters. Older adults with a spouse, sons and daughters tended to seek social support from a spouse, followed by sons, others and daughters, and older adults with sons and daughters tended to seek social support from sons, followed by others and daughters. (For details, see Table 2.) Older adults with sons and daughters showed a greater tendency to seek social support from sons, daughters and others relative to those with a spouse, sons and daughters; see Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Tendency of social support seeking from different sources among older adults in China

| Having spouses, sons and daughters | Having sons and daughters | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse | Sons | Daughters | Others | F | ƞ2 | Sons | Daughters | Others | F | ƞ2 | |

| Total | 0.72 (0.36) | 0.16 (0.27) | 0.04(0.17) | 0.07 (0.19) | 2414.87*** | 0.54 | 0.64 (0.39) | 0.14 (0.30) | 0.21 (0.31) | 2014.05*** | 0.40 |

| Age-group | |||||||||||

| Young-old | 0.74 (0.35) | 0.15 (0.25) | 0.04 (0.16) | 0.06 (0.18) | 2149.77*** | 0.58 | 0.60 (0.39) | 0.15 (0.30) | 0.24 (0.31) | 628.39*** | 0.36 |

| Old-old | 0.66 (0.39) | 0.21 (0.30) | 0.05 (0.18) | 0.08 (0.20) | 352.13*** | 0.43 | 0.66 (0.39) | 0.13 (0.30) | 0.19 (0.31) | 1408.11*** | 0.42 |

| Region | |||||||||||

| Cities | 0.75 (0.34) | 0.12 (0.23) | 0.07 (0.22) | 0.05 (0.17) | 597.55*** | 0.58 | 0.53 (0.43) | 0.27 (0.39) | 0.19 (0.31) | 192.60*** | 0.25 |

| Towns | 0.73 (0.36) | 0.17 (0.27) | 0.04 (0.15) | 0.07 (0.19) | 917.11*** | 0.55 | 0.65 (0.38) | 0.11 (0.27) | 0.23 (0.32) | 835.18*** | 0.44 |

| Rural areas | 0.70 (0.37) | 0.18 (0.28) | 0.04 (0.15) | 0.08 (0.19) | 917.45*** | 0.51 | 0.68 (0.38) | 0.11 (0.27) | 0.20 (0.31) | 1181.91*** | 0.47 |

Fig. 1.

Patterns of social support seeking among subgroups with different sources of support. Notes. ***p value < 0.001

Socio-demographic variations in the patterns of social support seeking

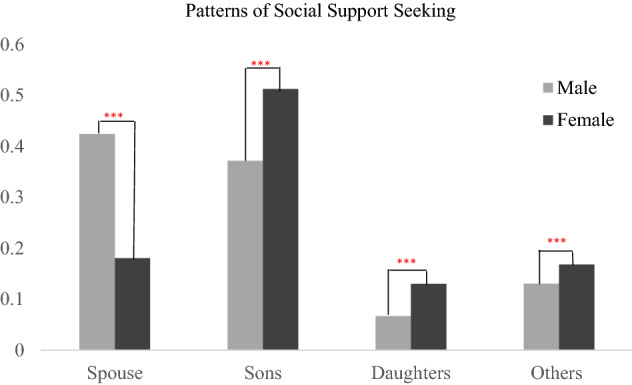

Analyses of gender differences revealed a significant source × gender interaction on social support seeking, F (3, 15,198) = 6.42, p = .001, η2 = .001, but the expected source × gender × subgroup interaction effect was nonsignificant, F (3, 15,198) = 0.11, ns, η2 < .001. Males tended to seek social support from a spouse, followed by sons, others and daughters; females tended to seek social support from sons, followed by a spouse, others and daughters. Males tended to seek support more from a spouse and less from sons, daughters and others relative to females; see Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Patterns of social support seeking among males and females. Notes. ***p value < 0.001

Analysis of age difference indicated that the subgroup × source × age-group three-way interaction effect on social support seeking was significant, F (3, 15,198) = 7.53, p < .001, η2 = .001. In the subgroup with a spouse, sons and daughters, older adults in China tended to seek social support from a spouse, followed by sons, others and daughters, and such source differences were stronger among young-old adults than among old-old adults. (For details, see Table 2.) Young-old adults in China tended to seek social support more from a spouse and less from sons relative to old-old adults in China, for spouses, F (1, 2051) = 15.46, p < .001, ƞ2 = .01, and for sons, F (1, 2051) = 14.41, p < .001, ƞ2 = .01. In the subgroup with sons and daughters, older adults in China tended to seek social support from sons, followed by others and daughters, and such source differences were stronger among old-old adults than among young-old adults. (For details, see Table 2.) Old-old adults in China tended to seek social support more from sons and less from others relative to young-old adults in China, for sons, F (1, 3015) = 19.12, p < .001, ƞ2 = .01, and for others, F (1, 3015) = 18.28, p < .001, ƞ2 = .01.

Parallel analyses for regional differences also revealed a significant subgroup × source × region interaction effect on social support seeking, F (6, 15,192) = 9.15, p < .001, η2 = .004. In the subgroup with a spouse, sons and daughters, older adults from cities tended to seek social support from a spouse, followed by sons, daughters and others, and older adults from towns and rural areas tended to seek social support from a spouse, followed by sons, others and daughters. Source differences in social support seeking were stronger among older adults from cities than among those from towns and rural areas. (For details, see Table 2.) Older adults from cities tended to seek support from their spouse more than did those from rural areas, F (2, 2050) = 3.30, p = .04, η2 = .01. Older adults from towns and rural areas tended to seek support more from sons and less from daughters relative to those from cities, for sons, F (2, 2050) = 6.96, p = .001, η2 = .01, and for daughters, F (2, 2050) = 7.21, p = .001, η2 = .01. In the subgroup with sons and daughters, older adults from cities tended to seek social support from sons, followed by daughters and others, older adults from towns and rural areas tended to seek social support from sons, followed by others and daughters. Such source differences in social support seeking were stronger among older adults from towns and rural areas compared with those from cities. (For details, see Table 2.) Older adults from towns and rural areas tended to seek social support from sons more but from daughters less relative to those from cities, for sons, F (2, 3014) = 33.99, p < .001, η2 = .02, and for daughters, F (2, 3014) = 67.32, p < .001, η2 = .04.

Discussion

In the current study, we examined the patterns of social support seeking and socio-demographic variations using a nationally representative sample of older adults in China. We found that a spouse was the most cited source of social support among older adults in China if they had a spouse, sons and daughters, whereas sons served as the most frequently used source of social support if they had only sons and daughters. This pattern was more salient among old-old adults and old adults from towns or rural areas than among young-old adults and older adults from urban areas. Relative to older females, older males in China tended to seek more social support from a spouse, sons or others, and seek less social support from daughters.

The difference in the primary source of social support between the two subgroups may suggest that older adults in China tend to rely on a spouse for support first and then turn to sons for compensation when the spouse is unavailable. These results provide a clear contrast from previous findings that observed adult children as the primary support providers for Chinese older adults (Dai et al. 2016; Tsai and Lopez 1998). This may be because previous studies only reflected the pattern of support seeking in the largest subgroup of older adults in China—those who only have sons and daughters. Our findings contribute to the literature by highlighting the importance of stratifying the availability of social support when examining the tendency of social support seeking.

Across the two subgroups, older adults in China prefer to seek social support from spouses or sons relative to daughters or non-family members. This is the first evidence showing that the tendency to choose close family members over non-family members exists in the process of social support seeking. Extending previous findings on social preferences, social network characteristics, trust and prosocial behaviors (Fung et al. 2001, 2008; Gong et al. 2017; Li and Fung 2013), and selectively seeking social support from close family members may also be an important regulatory strategy for older adults in China to achieve emotionally meaningful goals.

This study reveals an interesting gender-type pattern of social support seeking across two subgroups. That is, older men in China seek social support from their spouse more and from all other sources less relative to older women in China. These findings are commensurate with previous findings that show that older men primarily rely on a spouse for support and older women sought support from more diverse sources across cultures (Chen et al. 2018; Cutrona 1996; Rossi and Rossi 1990). If this pattern would be shown to be consistent in cultures besides the USA and China, this could represent a universal experience that intergenerational support exchanges are governed by gender roles.

Our findings show that old-old adults tend to seek social support from sons more and from the spouse and others less compared to young-old adults. This might be because old-old adults in China endorse Confucian ethics that prioritize father–son dyads more than other dyads, and thus they tend to rely more on sons and rely less on spouses or close others relative to young-old adults (Yang 1993). This finding may also be explained by poorer marital relationships in older generations. Among old-old adults, marriages were mostly arranged by parents and are more emotionally distancing and rarely egalitarian (Pimentel 2000).

We observe consistent regional differences in support seeking from sons and daughters across two subgroups: Older adults from towns and rural areas tend to seek social support from sons more and from daughters less compared with those from cities. More importantly, only a very small portion of older adults in China seems to rely on adult daughters for social support. This result is in sharp contrast to Western reports documenting that mother–daughter bonds are the most intimate, consistent and enduring family relationships and daughters are more responsive to parents’ needs and devote more resources to support aging parents relative to sons (Antonucci and Akiyama 1987; Haberkern et al. 2012; Sarkisian and Gerstel 2004). However, this concurs with other findings showing that aging parents in China prefer to have intergenerational support exchanges with sons in both one-child and multi-child families (Chen and Jordan 2018). Hence, Confucian male-superior gender norms and associated son preferences may be still prevalent in family practices of modern Chinese societies, especially in rural China.

In closing, several limitations of this study are worth noting. First, we used cross-sectional data. Future studies should utilize longitudinal data to disentangle cohort differences from age-related changes in social support seeking. Second, this study assessed social support seeking with three simple items, which may subject to social desirability bias. An in-depth examination of specific forms of social support (e.g., implicit support, tangible or financial support) with more objective methods may be fruitful. Lastly, this study is descriptive and does not investigate the potential confounding effects of living arrangement. Future studies should rule out this possibility and examine how living arrangement or cultural factors would explain the observed relationships.

In conclusion, this study provides a reasonably accurate portrayal of the pattern of social support seeking among older adults in China. We found a hierarchically ordered pattern of social support seeking such that older adults prefer to seek social support from a spouse first and then turn to sons only when the spouse is unavailable or incapable of providing support. We also observed a strong trend of son preferences, which was even more salient among old-old adults and older adults from rural China. As the match of support provision with support receivers’ preferences may optimize health benefits, this study suggests that psychosocial interventions aiming to facilitate the proactive involvement of spouses or sons in social support exchanges may be efficacious in the population of older adults in China. Meanwhile, developing social support groups or home-based care in the neighborhoods may be culturally competent to supplement the eroding functions of the family in modern China.

Acknowledgements

The preparation of manuscript is supported by Youth Grant of National Science Foundation (31500908) and Young Scholar Career Development Plan in Humanistic and Social Science at Wuhan University.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Footnotes

Responsible editor: Susanne Iwarsson.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ajrouch KJ, Blandon AY, Antonucci TC. Social networks among men and women: the effects of age and socioeconomic status. J Gerontol Soc Sci. 2005;60B:8311–8317. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.6.S311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Akiyama H. An examination of sex differences in social support among older men and women. Sex Roles. 1987;11:737–745. doi: 10.1007/BF00287685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL. The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science. 2006;312:1913–1915. doi: 10.1126/science.1127488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Healthy Aging and Development Studies (2015) The Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey (CLHLS)-cross sectional data (2011). Peking University Open Research Data Platform, V1

- Chen J, Jordan LP. Intergenerational support in one- and multi-child families in China: does child gender still matter? Res Aging. 2018;40:180–204. doi: 10.1177/0164027517690883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Short SE. Household context and subjective well-being among the oldest old in China. J Fam Issues. 2008;29:1379–1403. doi: 10.1177/0192513x07313602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Giles J, Wang Y, Zhao Y. Gender patterns of eldercare in China. Fem Econ. 2018;24:54–76. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2018.1438639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Social relationships and health. Am Psychol. 2004;59:676–684. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong Z, Silverstein M. Intergenerational support and depression among elders in rural China: do daughters-in-law matter? J Marriage Fam. 2008;70:599–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00508.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cong Z, Silverstein M. Parent’s preferred caregiving in rural China: gender, migration, and intergenerational exchanges. Ageing Soc. 2012;34:727–752. doi: 10.1017/s0144686x12001237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE. Social support as a determinant of marital quality. In: Pierce GR, Sarason BR, Sarason IG, editors. Handbook of social support and the family. New York: Plenum Press; 1996. pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Zhang C, Zhang B, Li Z, Jiang C, Huang H. Social support and the self-rated health of older people: a comparative study in Tainan Taiwan and Fuzhou Fujian province. Medicine. 2016;95:e3881. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000003881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel Schetter C. Moving research on health and close relationships forward-a challenge and an obligation: introduction to the special issue. Am Psychol. 2017;72:511–516. doi: 10.1037/amp0000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrer R, Stansfeld SA. How gender affects patterns of social relations and their impact on health: a comparison of one or multiple sources of support from “close person”. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:811–825. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Iglesias HR, Antonucci TC. Convoys of social support in Mexico: examining socio-demographic variation. Int J Beh Dev. 2016;40:324–333. doi: 10.1177/0165025415581028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung HH. Aging in culture. Gerontologist. 2013;53:369–377. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung HH, Ng SK. Age differences in the sixth personality factor: age differences in interpersonal relatedness among Canadians and Hong Kong Chinese. Psychol Aging. 2006;21:810–814. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.4.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung HH, Lai P, Ng R. Age differences in social preferences among Taiwanese and mainland Chinese: the role of perceived time. Psychol Aging. 2001;16:351–356. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.16.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung HH, Stoeber FS, Yeung D, Lang FR. Cultural specificity of socioemotional selectivity: age differences in social network composition among Germans and Hong Kong Chinese. J Gerontol Psychol Sci. 2008;63:156–164. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.3.P156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung HH, Ho YW, Tam KP, Tsai J. Value moderates age differences in personality: the example of relationship orientation. Pers Indiv Differ. 2011;50:994–999. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X, Zhang F, Fung HH. Are older adults more willing to donate? The roles of donation form and social relationship. J Gerontol Psychol Sci. 2017 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Aranda MP, Silverstain M. The impact of out-migration on the inter-generational support and psychological wellbeing of older adults in rural China. Ageing Soc. 2009;29:1085–1104. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X0900871X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haberkern K, Schmid T, Neuberger F, Grignon M (2012) The role of the elderly as providers and recipients of care. In: Organization for economic co-operation and development (OECD) (ed) The future of families to 2030, OECD, Paris, pp 189–257

- Jiang Q, Sánchez-Barricarte JJ. The 4-2-1 family structure in China: a survival analysis based on life tables. Eur J Ageing. 2011;8:119. doi: 10.1007/s10433-011-0189-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Sherman DK, Taylor SE. Culture and social support. Am Psychol. 2008;63:518–526. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulich SJ, Zhang R. The multiple frames of “Chinese” values: from tradition to modernity. In: Bond M, editor. Oxford handbook of Chinese psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 241–278. [Google Scholar]

- LaFave D. Family support and elderly well-being in China: evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Ageing Int. 2017;42:142–158. doi: 10.1007/s12126-016-9268-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S (1991) The characteristics and economic guarantees of social support for the aged in China. In: Sciences CAoS (ed) A selection of papers presented at the international symposium on population aging in China, New World Press, Beijing, pp 149–157

- Li T, Fung HH. Age differences in trust: an investigation across 38 countries. J Gerontol Psychol Sci. 2013;68:347–355. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Ji Y, Chen T. The roles of different sources of social support on emotional well-being among Chinese elderly. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e90051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JH. What Confucian philosophy means for Chinese and Asian psychology today: indigenous roots for a psychology of social change. J Pac Rim Psychol. 2014;8:35–42. doi: 10.1017/prp.2014.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JH, Li M, Yue X. Chinese social identity and intergroup relations: the influence of benevolent authority. In: Bond MH, editor. Oxford handbook of chinese psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 579–598. [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, Han W. Living arrangements and older adults’ psychological well-being and life satisfaction in China: does social support matter? Fam Relat. 2018;67:567–584. doi: 10.1111/fare.12326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel EE. Just how do I love thee? Marital relations in urban China. J Marriage Fam. 2000;62:32–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00032.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi AS, Rossi PH. Of human bonding: parent-child relations across the life course. New York: Aldine de Gruyer; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian N, Gerstel N. Explaining the gender gap in help to parents: the importance of employment. J Marriage Fam. 2004;66:431–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2004.00030.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng X (2005) Families and intergenerational relationships in China. Globalization, tradition, social transformation, and elderly care. In: Steinbach A (ed) Generatives Verhalten und Generationenbeziehungen, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden, pp 213–232

- Song L, Li S, Feldman MW. Out-migration of young adults and gender division of intergenerational support in rural China. Res Aging. 2012;34:399–424. doi: 10.1177/0164027511436321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suanet B, Antonucci TC. Cohort differences in received social support in later life: the role of network type. J Gerontol Soc Sci. 2016;72:706–715. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Sherman DK, Kim HS, Jarcho J, Takagi K, Dunagan MS. Culture and social support: who seeks it and why? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;87:354–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treas J, Wang W (1990) Inter-generational beliefs of the aged in Shanghai. In: Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (ed) A selection of papers presented at the international symposium on populations aging in China, New World Press, Beijing, pp 350–362

- Tsai DT, Lopez RA. The use of social supports by elderly Chinese immigrants. J Gerontol Soc Work. 1998;29:77–94. doi: 10.1300/J083v29n01_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Montez JK. Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Beh. 2010;51:s54–s66. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz BL, Carr D, Nesse RM, Wortman C. The effect of widowhood on older adults’ social participation: an evaluation of activity, disengagement and continuity theories. Gerontologist. 2002;42:522–533. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C, Lin E. There are homes at the four corners of the seas: acculturation and adaption of overseas. In: Bond MH, editor. Oxford handbook of chinese psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- White AM, Philogene GS, Fine L, Sinha S. Social support and self-reported health status of older adults in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1872–1878. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.146894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K. Chinese social orientation: a social-interactive perspective. In: Yang K, editor. Chinese psychology and behaivor: indigenous research. Taipei: Guiguan Publisher; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung D, Fung HH, Lang FR. Gender differences in social network characteristics and psychological well-being among Hong Kong Chinese: the role of future time perspective and adherence to Renqing. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11:45–56. doi: 10.1080/13607860600735820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y. Introducation to the Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey (CLHLS) In: Zeng Y, Perston DL, Vlosky DA, Gu D, editors. Healthy longevity in China, vol demographic methods and population analysis. Dordrecht: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]